You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

n Continued from page C4<br />

Union completed. Those 100,000 people<br />

weren’t accepted as <strong>Armenian</strong>s, but as<br />

foreigners. After arriving they figured<br />

that out, but it was too late,” he told me.<br />

When I tried to broach the subject<br />

one more time, gently reminding him<br />

that the repatriates who came in the 40s<br />

must have contributed, at the very least<br />

through their way of life, through their<br />

cuisine and customs, something to the<br />

fabric of society , he said, “What good is<br />

it when you bring people in 1946–48 and<br />

then you exile them to Siberia in 1949<br />

If you didn’t want these people, if you<br />

brought them by mistake, why not just<br />

send them back where they came from<br />

Why do you exile them”<br />

There was more to his anger than appeared<br />

on the surface. He understood<br />

what the loss of homeland meant. More<br />

than that, he understood the hunger for<br />

returning. For him it was about their<br />

collective fate, their collective suffering,<br />

the Genocide that always hung over<br />

their heads. These feelings are portrayed<br />

in his paintings from that time period.<br />

With all that this artist has seen in his<br />

life, the one thing he doesn’t have is regret.<br />

“It was my destiny to move here, however.<br />

I have never regretted coming. I have never<br />

thought about leaving or living somewhere<br />

else. I always wanted to live in my<br />

country among my people,” he told me.<br />

His thoughts about repatriation today<br />

are ambiguous but of one conviction<br />

he is sure. “Repatriation today Don’t<br />

you think it would be better for them<br />

to find ways of hampering people from<br />

leaving the country” he asked. “The Diaspora<br />

Ministry should concern itself<br />

with finding ways of keeping people in<br />

the country, then trying to bring back<br />

those who left.”<br />

Starting over in Gyumri<br />

When the Hakobyan family repatriated<br />

to Armenia, they were settled in Gyumri,<br />

Armenia’s second largest city. They lived<br />

there for five years. Hakob was 40 years<br />

old. He was known in some artistic circles<br />

in Armenia already because he had<br />

donated 10 of his best paintings a few<br />

years earlier to the National Art Gallery.<br />

Life in Gyumri was difficult. “They<br />

didn’t even ‘give’ me a studio to paint,” he<br />

said. “Instead of all the accolades, if they<br />

had allowed me to have a small room to<br />

turn into a studio instead of working in a<br />

corner of my tiny apartment, that would<br />

have served me better.” He had brought<br />

some canvas with him when he moved,<br />

and after that was finished, he bought<br />

what he could find, which was of very<br />

poor quality. “A lot of my early paintings<br />

have been ruined because of that poor<br />

quality of canvas.” He still finds it ironic<br />

that they would only have poor quality<br />

canvas upon which paintings that were<br />

sometimes worth thousands of dollars<br />

would be painted. “Nothing made sense,”<br />

he said, shaking his head.<br />

“That’s how our life was in Gyumri. I<br />

don’t want to complain that I had to<br />

work under those conditions. For me the<br />

most important thing was to be able to<br />

paint in Armenia. I didn’t want to take a<br />

break. I didn’t want people think that I<br />

couldn’t succeed here,” he explained.<br />

After his first solo exhibition, he slowly<br />

began to establish himself as a painter<br />

in the homeland. Although even art was<br />

stifled under the Soviet regime, Hakobyan<br />

stressed that it wasn’t always possible to<br />

<strong>Armenian</strong> <strong>Reporter</strong> Arts & Culture February 21, 2009<br />

suffocate every human inspiration. “Look<br />

at Minas Avedissian. You can’t always take<br />

the art out of the man,” he told me, referring<br />

to a fellow artist.<br />

What would his life’s journey been<br />

had he not moved to Armenia “If I had<br />

stayed in Egypt, I might have become<br />

a different artist,” he said. The painter<br />

was also astute. He knew never to complain<br />

or demand in order to survive in<br />

the system. “I had no confrontations,<br />

but I retained my freedom in my sphere<br />

– through my art.”<br />

Thoughts about the nation<br />

“I have lived half my life outside of Armenia,<br />

then I lived under Soviet rule for<br />

27 years and 17 years in independence,”<br />

he said. He feels that we have suffered<br />

as a nation because of our size. “If we<br />

had been 30 million instead of 3 million,<br />

do you think that the Turks could have<br />

slaughtered us like sheep Therefore being<br />

a small nation is a sin,” he stressed.<br />

For Hakobyan there is an important<br />

distinction to be made. “Independence<br />

was given to us; we didn’t win it. For<br />

600 years we never had independence.<br />

Did we ever think about independence<br />

Therefore we never wanted it and now<br />

we don’t know what to do with it. We<br />

still want odars to come and govern us,”<br />

he told me. And about victories “Yes,<br />

we won in Karabakh. But look at what<br />

the price was – thousands dead, hundreds<br />

of thousands of displaced people,<br />

more than a million left the country.<br />

If this is victory, then bravo, we won,”<br />

he said, his voice straining. So there is<br />

some bitterness in this man’s spirit.<br />

And what about the state of the country<br />

today “After 600 years of slavery and<br />

survival, we have learned how to survive,<br />

but in the process we have become individualistic.<br />

We think only of taking care<br />

of ourselves. That is why we can’t move<br />

forward today. It’s all about the individual.<br />

There are no unifying elements.”<br />

He shifted in his chair and continued.<br />

“My dear, we don’t have normal relations<br />

with our neighbors. Two of them are our<br />

enemies; the neighbor to the north we<br />

want to turn into an enemy; the one<br />

to the south is the enemy of the rest of<br />

the world, and the other one [Russia],<br />

with whom we have no natural borders<br />

and who is our former ‘owner,’ is in our<br />

country protecting our borders.”<br />

His disenchantment causes waves of<br />

sadness to rush over him. He is frustrated<br />

because he is the first to admit that<br />

we are a nation of gifted people. “The <strong>Armenian</strong><br />

has limitless abilities. Before the<br />

Soviets, the <strong>Armenian</strong> was another sort<br />

of person, a totally different person,” he<br />

said. “We had genius; we had the farmer,<br />

but they turned him into a kolkhoznik;<br />

we had the artisan but they turned him<br />

into a laborer; and the entrepreneur was<br />

sentenced to exile or death. That is what<br />

the Soviet regime bequeathed us.”<br />

Studio visit<br />

Finding that our conversation had exhausted<br />

him, I suggested we move to his<br />

studio to look at his new creations. His<br />

demeanor changed, and the sadness and<br />

frustration subsided as he stepped into<br />

his oasis.<br />

As he walked around his studio, he<br />

told me that he works every day for a<br />

few hours. Today he produces about<br />

20–25 pieces annually. “I don’t have the<br />

same enthusiasm as I did, but creating<br />

something new still exists in me,” he<br />

said, pointing to shelves of newly created<br />

metal sculptures.<br />

Over the past year, Hakobyan has<br />

started creating sculptures out of scrap<br />

metal parts. “Every weekend I go to the<br />

Vernissage and buy these metal parts. After<br />

creating the sculpture I incorporate<br />

in into my paintings. I have made about<br />

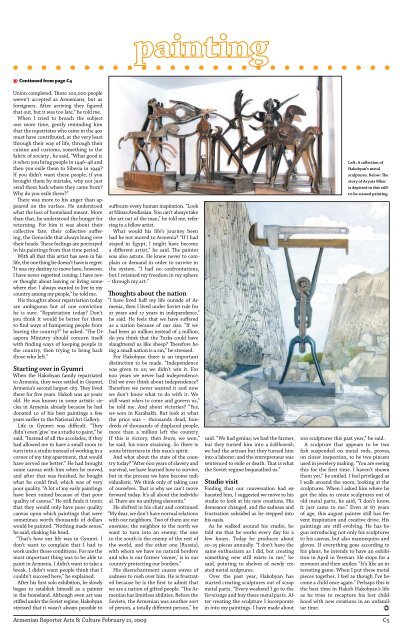

Left: A collection of<br />

Hakobyan’s metal<br />

sculptures. Below: The<br />

story of Aryuts Mher<br />

is depicted in this stillto-be-named<br />

painting.<br />

100 sculptures this past year,” he said.<br />

A sculpture that appears to be two<br />

fish suspended on metal rods, proves,<br />

on closer inspection, to be two pincers<br />

used in jewelery making. “You are seeing<br />

this for the first time. I haven’t shown<br />

them yet,” he smiled. I feel privileged as<br />

I walk around the room, looking at the<br />

sculptures. When I asked him where he<br />

got the idea to create sculptures out of<br />

old metal parts, he said, “I don’t know.<br />

It just came to me.” Even at 87 years<br />

of age, this august painter still has fervent<br />

inspiration and creative drive. His<br />

paintings are still evolving. He has begun<br />

introducing not only his sculptures<br />

to his canvas, but also mannequins and<br />

gloves. If everything goes according to<br />

his plans, he intends to have an exhibition<br />

in April in Yerevan. He stops for a<br />

moment and then smiles: “It’s like an interesting<br />

game. When I put these metal<br />

pieces together, I feel as though I’ve become<br />

a child once again.” Perhaps this is<br />

the best time in Hakob Hakobyan’s life<br />

as he tries to recapture his lost childhood<br />

with new creations in an unfamiliar<br />

time.<br />

f<br />

C5