You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Nancy Abelmann, Josie Sohn Revisiting the Developmentalist Era Mother in 2000s South <strong>Korean</strong> Film<br />

with her diving. And this young diver now takes a perfect<br />

stranger into her home w<strong>here</strong> everything – the old<br />

dresser, photographs, and so on – is too familiar for comfort<br />

to the guest. When Na-yŏng wakes after spending<br />

her first night in the village in utter disbelief, Yŏn-sun, as<br />

real as real can be, enters her room with a small breakfast<br />

table. The seaweed soup that Na-yŏng had refused at<br />

home and the pickled crab that her mother had embarrassingly<br />

demanded at the aforementioned evening out<br />

quietly lets us know that Yŏn-sun is and always has been<br />

a kind and generous woman.<br />

The film is propelled, as we wind the exquisite island<br />

paths of yesteryear (interestingly, entirely different than<br />

the crime-ridden dusty ways in the village in Mother), by<br />

the ever-so-innocent love story of Yŏn-sun and the man<br />

who we know will become Na-yŏng’s father – the island<br />

postman. In what <strong>Korean</strong> cinema scholar Steven Chung<br />

describes as the “spectacularizing enlightenment” (18),<br />

theirs is an enlightenment story in which the postman<br />

teaches illiterate Yŏn-sun, opening her world, allowing<br />

her, literally, to name it (see Figure 4). 4 And Na-yŏng is<br />

t<strong>here</strong> to test her mother from the primers that her fatherto-be<br />

has given her mother. In a nearly classical developmentalist<br />

spectacle, we look on as Na-yŏng witnesses the<br />

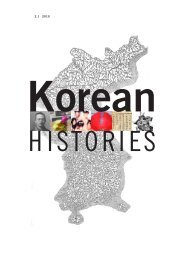

arrival of the island’s first bus, and we are t<strong>here</strong> to capture<br />

(in a photograph) Na-yŏng, Yŏn-sun, and, yes, the postman<br />

who has peeped out<br />

from behind the bus,<br />

in the nick of time for<br />

posterity (see Figure<br />

5). How then does the<br />

film allow us to thread<br />

time: from literacy and<br />

the first village bus to<br />

the hardened antics of<br />

a middle-aged laboring<br />

woman? Are we to<br />

wax nostalgic for the<br />

days of yore before the<br />

ravages of advanced<br />

doggy-dog capitalism<br />

– times in which the<br />

Yŏn-sun could innocently<br />

marvel at the<br />

5. My mother, the mermaid (2004)<br />

rural postman’s knowledge<br />

and worldly ways? Are we to nod knowingly that<br />

the kindness of Na-yŏng’s father’s variety, a throw-back<br />

to island days and ways – somehow out of step with the<br />

times – is enough to drive a woman crazy? Indeed, the film<br />

opens on the adult mother at the funeral of her husband’s<br />

buddy who has died leaving her husband the guarantor<br />

of his debt: we see all of the antics of mourning, but in<br />

her case the nearly humorous mourning of her husband’s<br />

ill-founded generosity through which he no doubt squandered<br />

her hard earned savings.<br />

The climax of Na-yŏng’s suture is the moment in which<br />

Na-yŏng and her child-mother are most integrated, a<br />

moment in which the time traveler seems to touch, not<br />

just witness, her mother’s past. This is also the moment<br />

when Na-yŏng will call Yŏn-sun, “Mom,” instead of her<br />

name. Yŏn-sun has nearly drowned, diving one too many<br />

times in the throes of her mourning the news of the<br />

postman’s relocation. As Na-yŏng nurses her mother at<br />

the sickbed, Yŏn-sun confides in Na-yŏng that it wasn’t<br />

until she learned from a neighbor that she had been an<br />

orphaned child, picked up by her late non-biological<br />

mother. Yŏn-sun continues that for a time she thought that<br />

this explained her sometimes hollow heart and frightening<br />

sadness. But she goes on, “[In fact] it wasn’t that at<br />

all, I felt all that because I wanted to see my [biological]<br />

mother.” And with the remarks that follow this comment,<br />

4 We cite this idea from Steven Chung’s 2008 presentation at the University of Illinois Korea Workshop, “Enlightenment Discourse and <strong>Korean</strong> Peninsular Cinema,” in which he argues that many films from the postwar<br />

era staged an “enlightenment spectacle.” A revised version of this presentation is forthcoming as “Modalities of Enlightenment in 20th Century <strong>Korean</strong> Cinema” in positions.<br />

40 <strong>Korean</strong> <strong>Histories</strong> 3.2 2013