Shakespeare - Athena

Shakespeare - Athena

Shakespeare - Athena

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

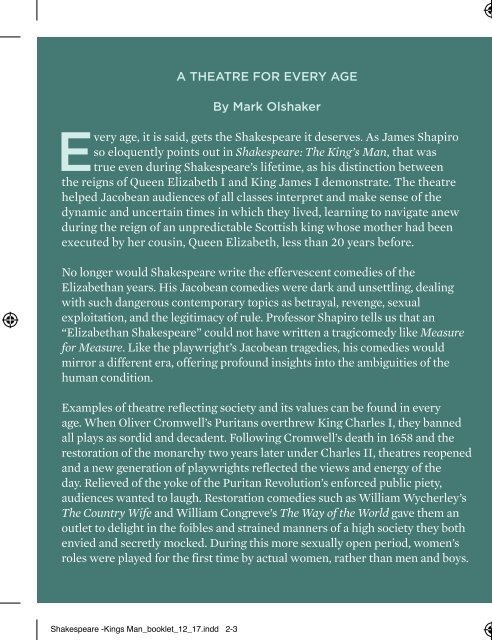

A THEATRE FOR EVERY AGE<br />

By Mark Olshaker<br />

Every age, it is said, gets the <strong>Shakespeare</strong> it deserves. As James Shapiro<br />

so eloquently points out in <strong>Shakespeare</strong>: The King’s Man, that was<br />

true even during <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s lifetime, as his distinction between<br />

the reigns of Queen Elizabeth I and King James I demonstrate. The theatre<br />

helped Jacobean audiences of all classes interpret and make sense of the<br />

dynamic and uncertain times in which they lived, learning to navigate anew<br />

during the reign of an unpredictable Scottish king whose mother had been<br />

executed by her cousin, Queen Elizabeth, less than 20 years before.<br />

No longer would <strong>Shakespeare</strong> write the effervescent comedies of the<br />

Elizabethan years. His Jacobean comedies were dark and unsettling, dealing<br />

with such dangerous contemporary topics as betrayal, revenge, sexual<br />

exploitation, and the legitimacy of rule. Professor Shapiro tells us that an<br />

“Elizabethan <strong>Shakespeare</strong>” could not have written a tragicomedy like Measure<br />

for Measure. Like the playwright’s Jacobean tragedies, his comedies would<br />

mirror a different era, offering profound insights into the ambiguities of the<br />

human condition.<br />

Examples of theatre reflecting society and its values can be found in every<br />

age. When Oliver Cromwell’s Puritans overthrew King Charles I, they banned<br />

all plays as sordid and decadent. Following Cromwell’s death in 1658 and the<br />

restoration of the monarchy two years later under Charles II, theatres reopened<br />

and a new generation of playwrights reflected the views and energy of the<br />

day. Relieved of the yoke of the Puritan Revolution’s enforced public piety,<br />

audiences wanted to laugh. Restoration comedies such as William Wycherley’s<br />

The Country Wife and William Congreve’s The Way of the World gave them an<br />

outlet to delight in the foibles and strained manners of a high society they both<br />

envied and secretly mocked. During this more sexually open period, women’s<br />

roles were played for the first time by actual women, rather than men and boys.<br />

Subsequent decades saw the beginnings of a new type of feel-good theatre,<br />

but one that reflected a society preoccupied with making things “right” and<br />

proper. This impulse reached its preposterous nadir in 1681 with Nahum<br />

Tate’s rewriting of King Lear. Tate removed the Fool and his acerbic social<br />

commentary and substituted a new, upbeat conclusion to <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s<br />

tragedy. In Tate’s version, Cordelia doesn’t die. Instead, she marries Edgar<br />

and they live happily ever after—a model of how audiences were expected<br />

to live their own lives.<br />

In the Victorian period, a newly industrialized and increasingly powerful<br />

Britain was displaying its prowess with stage spectacles, musical<br />

extravaganzas, and elaborate comic operas. As the 19th century progressed,<br />

Britain’s rather straight-laced society grew to favor domestic comedies and<br />

sentimental dramas with elements of realism, like Arthur Wing Pinero’s<br />

Trelawney of the “Wells.” Contrast this with the “angry young men” of<br />

London’s Royal Court Theatre in the late 1950s, where John Osborne’s Look<br />

Back in Anger stunned playgoers with its frank depiction of middle-class<br />

life and frustrations in the years following World War II.<br />

Nowhere, perhaps, does the relationship between theatre and society<br />

emerge more clearly than in comparing productions of the same<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>an plays in two distinct eras. For a vivid demonstration, we can<br />

thank Laurence Olivier and Kenneth Branagh, each of whom committed<br />

memorable versions of Henry V and Hamlet to film.<br />

Olivier’s Henry V, produced during World War II as a morale booster,<br />

portrays a resolute and determined king, rallying the population in a<br />

righteous cause against a formidable enemy. The beautiful film attempts<br />

something midway between stage and screen. It begins with a staging in<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s Globe, but when Henry’s army reaches France, the movie<br />

transports us to a semi-realistic, semi-storybook setting.<br />

Branagh’s 1989 film is a Thatcher-era, post-Falklands War meditation on<br />

1<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> -Kings Man_booklet_12_17.indd 2-3<br />

12/17/12 5:27 PM