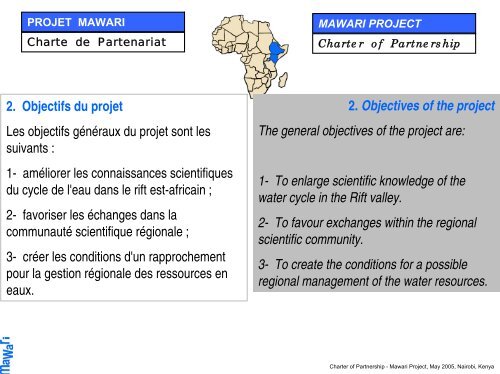

projet mawari - MaWaRi.net

projet mawari - MaWaRi.net

projet mawari - MaWaRi.net

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

CPT Sean McWilliams on patrol in Baghdadabout four blocks from where an improvisedexplosive device (IED) wouldlater strike this same unarmored Humvee.that you are not indispensable; a new leader has assumedyour duties. Realizing that the mission continues without youtakes awhile to get your head around. Making things worse,there was a perceived stigma associated with rear detachment.The other wounded Soldiers and I felt like, “I am not adrug user, criminal, problem maker or newbie replacement.Why, then, am I being lumped into the same category?”Eventually, my time in purgatory ended. Unlike a lot ofothers, I got to rejoin my unit. The others stayed and waitedfor the unit to return. When I saw these Soldiers again, theyhad a number of complaints about how they were treated.This phase creates some additional challenges for thewounded Soldier. As this was a busy time for rear detachments,the wounded leaders were often assigned dutiesthat prevented them from being part of the reintegration.Arms-room inventories, convoy movement and other preparationsoften drew heavily from the pool of available,wounded leaders. They told me that although they felt beingbusy was good for them, they felt insulated from the reintegrationprocess. A number of Soldiers told me that they felttheir contributions during the deployment were not beingpublicly recognized. It did not help that rear detachmentSoldiers were in BDUs [battle dress uniforms] and returningsoldiers were in DCUs [desert camouflage uniforms].On my unit’s second deployment, we had a higher numberof casualties, and the entire brigade made an effort to incorporatethem into welcome-home or recognition ceremonies.We collectively were aware that the wounded Soldier hadstrong feelings of loyalty to the returning unit and wanted tobe part of the team again. One technique we found successfulwas a large ceremony after block leave. The brigade conducteda follow-on ceremony where we brought a number ofwounded soldiers to participate. This was vital to recognizingtheir accomplishments and reintegrating the “team.”One effect of my experience was a kind of empathy forSoldiers who by virtue of their injuries were moved out of aleadership position. I went out of my way to ensure thatwounded leaders were not at a disadvantage.One challenge I observedwas the reintegration of wounded leadersinto their old positions. Many returningleaders found it difficult to understandthat a junior leader hadstepped up to fill their position. TheSoldiers had grown accustomed to relyingon the junior leader to make decisions,so the reintegration of the seniorleader took a little time. Subtle secondguessingof the returning leader wasunintentional, yet it jeopardized theplatoon’s coherence. In a couple ofcases, I saw this create some resentment,but most platoons were able towork through this and reintegrate as a team.In more concrete terms, my experience made me emphasizethe reality of combat in our training. As an HHCcommander, I could partially influence how we conductedCPT Sean McWilliams waits for his flight home in theevacuation holding area at Ramstein Air Force Basein Germany, in October 2003. This photo was takennearly two weeks after the attack that wounded him.February 2008 ■ ARMY 53