Driven By Demand - Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society

Driven By Demand - Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society

Driven By Demand - Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

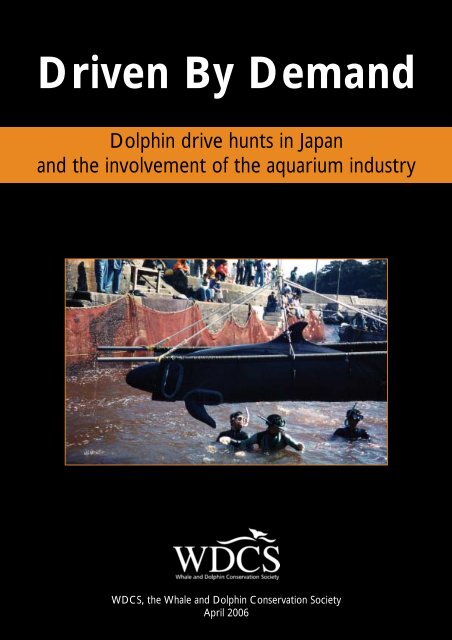

<strong>Driven</strong> <strong>By</strong> <strong>Dem<strong>and</strong></strong><strong>Dolphin</strong> drive hunts in Japan<strong>and</strong> the involvement of the aquarium industryWDCS, the <strong>Whale</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Dolphin</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Society</strong>April 2006

All information in this report may be reproduced for educational purposes provided written credit isgiven to WDCS. The report itself <strong>and</strong> photographs contained within it may not be reproduced withoutthe prior written approval of WDCS. We have taken care to ensure the accuracy of information withinthis report. We are concerned about whale <strong>and</strong> dolphin hunts wherever they occur, <strong>and</strong> welcomecomments, updates <strong>and</strong> new information. Please send information to: info@wdcs.org.WDCS UKBrookfield House, 38 St. Paul Street, Chippenham, Wiltshire SN15 1LJ, U.K.Tel: +44 (0)1249 449 500, Fax: +44 (0)1249 449 501, www.wdcs.orgWDCS North America70 East Falmouth Hwy, East Falmouth, MA 02536, USATel: +1 508 548 8328, Fax: +1 508 457 1988, www.whales.orgWDCS GermanyWDCS, Altostr. 43, 81245 Munich, GermanyTel: +49 (0) 89 6100 2393, Fax: +49 (0) 89 6100 2394, www.wdcs-de.orgWDCS AustralasiaWDCS, PO Box 720, Port Adelaide Business Centre, Port Adelaide, South Australia 5015, AustraliaTel: 1300 360 442, Fax: 088 44 74 211, www.wdcs.org.auWDCS ArgentinaWDCS, Francisco Beiro 3731, (B1636CHM) - Olivos, Prov. Buenos Aires, ArgentinaTel+Fax: +54 11 479 06 870, www.wdcs.orgAcknowledgementsThis report was written by Courtney S.Vail <strong>and</strong> Denise Risch, <strong>and</strong> edited by Cathy Williamson.Japanese translation was provided by: Sakae Hemmi, Elsa Nature Conservancy.Our sincere thanks to Sakae Hemmi, Nanami Kurasawa, Sue Fisher, Mark Simmonds, Hardy Jones,Philippa Brakes, Clare Perry <strong>and</strong> Nicolas Entrup for their help in the production of this report.© Copyright 2006 WDCS. All rights reserved. Report design by: Roman Richter.The authors wish to point out that they have made every effort to ensure credit is given to those persons whosematerials have been used in this report. Every effort has been made to identify contributors <strong>and</strong> to recognise thecopyright of any material incorporated. If any person is aware of any circumstances which suggest that theproper accreditation has not been given in respect of any material contained or referred to in the report they areasked to bring it to the attention of the authors <strong>and</strong> appropriate steps will be taken to accredit such materials.Readers may find some of the images in this report disturbing.Front cover <strong>and</strong> page three photo: Sakae Hemmi. Copyright: Elsa Nature Conservancy 2006. A falsekiller whale being selected by aquarium representatives at a drive hunt in Futo. Back page photo: IngridN Visser: bottlenose dolphin.WDCS, the <strong>Whale</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Dolphin</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Society</strong>, is an international charity dedicated to the conservation<strong>and</strong> welfare of whales, dolphins <strong>and</strong> porpoises worldwide. Established in 1987, <strong>and</strong> with offices in the UK,USA, Australia, Germany <strong>and</strong> Argentina, WDCS works to reduce <strong>and</strong> ultimately eliminate the continuingthreats to cetaceans <strong>and</strong> their habitats, whilst striving to raise awareness of these remarkable animals <strong>and</strong>the need to protect them in their natural environment. We achieve these objectives through a mix ofcampaigning, conservation, research, education <strong>and</strong> awareness raising initiatives.WDCS is a registered charity, No 1014795 <strong>and</strong> a company limited by guarantee. Registered in Engl<strong>and</strong> No 2737421.

<strong>Driven</strong> <strong>By</strong> <strong>Dem<strong>and</strong></strong><strong>Dolphin</strong> drive hunts in Japan<strong>and</strong> the involvement of the aquarium industryWDCS, the <strong>Whale</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Dolphin</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Society</strong>April 2006

4Foreword Sakae Hemmi, Researcher <strong>and</strong> Director, Marine Mammal Project, Elsa Nature ConservancySakae Hemmi, writer, has published 18 books, three of which achievedspecial recommendation for school children from the Japan LibraryAssociation. She has served as a volunteer for the Elsa NatureConservancy since 1976 <strong>and</strong> has worked to create awareness for animalconservation in Japan, including that of whales <strong>and</strong> dolphins.»If dolphins could speak human languages, <strong>and</strong>one of them kept in an aquarium wasinterviewed, she might say, “My family lived in theocean, freely swimming around. One day, all of asudden, we were chased by fishing boats, threatenedby noises from the banging of metal pipes, driven toa shallow inlet <strong>and</strong> confined there. My father diedfrom suffocation after becoming entangled in fishingnets. My mother was slaughtered with a knife forhuman consumption. My sister died of shock whenshe was lifted out of the water <strong>and</strong> my brotherdrowned during the capture procedure. Both of themwere processed for meat <strong>and</strong> eaten by humans <strong>and</strong>their pets. I myself survived, was brought into thisaquarium, taught tricks, <strong>and</strong> am working toentertain you.”You may think this story is imaginary, but it is not.It is a true story - a reality of the drive fisheryindustry in Japan. All readers of this report aresure to find it distressing.Nowadays, voices of worldwide criticism areincreasingly raised against Japan's dolphin drivehunts. This issue has already become animportant political issue to which more <strong>and</strong> moreinternational nature, environmental <strong>and</strong> animalprotection organizations are strongly opposed.In these circumstances it is extremely important,valuable <strong>and</strong> timely that WDCS has completed<strong>and</strong> published a detailed report on Japan's dolphindrive fishery industry. What is needed most nowis to clarify what the drive fishery industry really is<strong>and</strong> accurately convey it to people as widely aspossible. I am most delighted with this publicationas one of the people who has long worked on theissue to abolish these cruel drive hunts. I believethat human wisdom, sensitivity <strong>and</strong> warmheartednesswill never allow the cruelty of thedrive hunts described in this report to continue.This report discusses important facts concerningdolphin drive hunts in detail, including their briefhistory. Readers will be able to underst<strong>and</strong> thereality of the hunts, as well as their historicalprogress <strong>and</strong> changes, <strong>and</strong> come to underst<strong>and</strong>the present situation of the drive fishery industryin Japan.Indicating the actual number of traded dolphins,the authors of this report prove that dolphinscaught in drive hunts have been sold to aquariaboth at home <strong>and</strong> abroad, <strong>and</strong> conclude that anincreasing number of aquaria have a closerelationship with the drive fishery industry. Ibelieve this will be well understood by thereaders. Readers will be shocked to learn that agrowing number of aquaria, which have beenconsidered to be educational facilities to protectdolphins, obtain dolphins from drive hunts, which,whether directly or indirectly has the effect ofsustaining them <strong>and</strong> allowing unspeakablesuffering to be inflicted on individual animals.Furthermore, readers will be astonished to findthat the dem<strong>and</strong> for live dolphins from a growingnumber of aquaria threatens the survival of wilddolphins.<strong>Dolphin</strong>s are one of the most beloved <strong>and</strong>popular animals in the world. Many people whoare suffering from daily stress seek healingthrough dolphins in aquaria <strong>and</strong> special dolphinfacilities. However, this report makes it clear thatthose who need to be healed most are nothumans, but dolphins themselves. After readingthis report, readers may be less inclined to visitdolphin shows. Once the public witnesses theorigin of these animals, they will no longer wantto swim with dolphins in these facilities, nor seedolphins swim around <strong>and</strong> around in a small tank.I recommend this excellent report to all peoplewho are interested in dolphins, who love aquaria,who work in the aquarium industry, <strong>and</strong> alldolphin researchers. I hope that all who read thisreport will be encouraged to think about the issueof Japan's dolphin drive hunts. I would like toappeal, along with the authors of this report, thatit is you, the readers of this report, who hold thekey to the future life of dolphins in Japanesewaters.«

ContentsContentsIntroduction 6The hunts today 8Why the hunts continue 12Cooperation unveiled 17International trade in drive hunt dolphins 20The role of international zoo <strong>and</strong> aquarium organizations 23Drive hunts: Impact on dolphin welfare 25Drive hunts: Detrimental to cetacean conservation 29National legislation <strong>and</strong> the drive hunts 31In conclusion 32<strong>Whale</strong> <strong>and</strong> dolphin watching - the alternative 33How you can help 34Notes <strong>and</strong> references 35Photo: WDCS. Pilot whale.5

IntroductionIntroduction6Photo: WDCS. Pilot whale.

7IntroductionFishermen have killed small cetaceans (dolphins,porpoises <strong>and</strong> small whales) around the coastlinesof Japan for centuries. Currently, over 20,000 ofthese animals are killed every year in “drivehunts”, h<strong>and</strong>-held harpoon 1 <strong>and</strong> cross-bow hunts,<strong>and</strong> in so-called “small type coastal whaling”where harpoons are fired from a boat's bow. 2 Thespecies targeted by these hunts include Dall'sporpoises, Risso's dolphins, bottlenose dolphins,short-finned pilot whales, striped dolphins,spotted dolphins, false killer whales <strong>and</strong> Baird'sbeaked whales. Increasingly, these hunts havecome under international scrutiny, promptingconcern from bodies such as the InternationalWhaling Commission (IWC), on both welfare <strong>and</strong>conservation grounds. In the last 20 years, over400,000 small cetaceans have been killed inJapanese waters. 3One particularly controversial form of thesehunts, <strong>and</strong> the focus of this report, is the “drivehunt” (sometimes called the “drive fishery” or“oikomiryou” in Japanese), in which dolphins <strong>and</strong>small whales are corralled by boats <strong>and</strong> driven,sometimes by their hundreds, into shallow waterwhere they are killed for their meat <strong>and</strong> blubber.Not all the dolphins are killed, however. Agrowing <strong>and</strong> disturbing trend has surfaced thatlinks the thriving aquarium ('captivity') industry tothis archaic practice. Instead of driving dolphins totheir death for human consumption <strong>and</strong> fertilizer,or as a means of what might be described as“pest control”, resulting from claims that dolphinssignificantly compete for fish with fisherman,fishing cooperatives are collaborating withnational <strong>and</strong> international aquaria <strong>and</strong> marineamusement parks to select dolphins from thesehunts for public display <strong>and</strong> human-dolphininteraction programmes.These hunts present a significant threat to boththe welfare <strong>and</strong> conservation of the cetaceanpopulations they target. They continue contraryto the repeated recommendations of the IWC<strong>and</strong> its Scientific Committee <strong>and</strong> the Governmentof Japan's claims that it pursues a policy ofsustainable utilization of marine resources. 4Furthermore, the edible products of the dolphinstaken in these hunts are often highly polluted withcontaminants including mercury <strong>and</strong> organiccompounds such as PCBs, <strong>and</strong> can pose a risk tohuman consumers. 5Despite intense international criticism of theinhumane methods of slaughter employed, <strong>and</strong> asJapanese prefectures appeared to be on the vergeof ab<strong>and</strong>oning the hunts, the dem<strong>and</strong> for liveanimals to supply a growing number of marineparks <strong>and</strong> aquaria is emerging as a primarymotivating factor for the drive hunts to continuein Japan. This report explores the nature of thisdem<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> the role of the aquarium industrythat purchases live animals from these hunts. Thiscooperation between the aquarium industry <strong>and</strong>the drive hunts is a devastating development forJapan's dolphins.Photo: Bottlenose dolphins being driven into a corner during a drive hunt in Futo.

The hunts todayThe hunts today8Photo: Boats surround dolphins during a drive hunt in Futo.

9The hunts todayPhoto: Sakae Hemmi. © Elsa Nature Conservancy 2006. <strong>Dolphin</strong>s are surrounded during the round-up process in Futo harbour.“Drive hunts are conducted by a number of highspeed boats that spot a school of dolphins or smallwhales at sea. The boats form a semi-circle <strong>and</strong> herdthe animals to a harbor or port. Once in the port,the dolphins are surrounded by nets, which aregradually pulled tighter, trapping the animals into anincreasingly confined space. The dolphins are thencaught with a hook, have a rope tied around theirflukes <strong>and</strong> are then lifted by a winch onto the quayor onto a truck. They are then driven to a nearbywarehouse to be slaughtered.” 6This description of a typical drive hunt does notconvey the trauma experienced by the dolphinscaught in these round-ups. After being driveninto shallow coves, the fishermen kill thedolphins with crude methods, cutting theirthroats or stabbing them with spears.Unconsciousness <strong>and</strong> death are not alwaysimmediate, <strong>and</strong> some dolphins take manyminutes to die, thrashing about violently asblood pours from their wounds. Some of thedolphins suffocate during the round-up <strong>and</strong>slaughter, getting caught in the nets, weakened<strong>and</strong> unable to swim from the shock <strong>and</strong> stressof capture. 7 Many dolphins panic <strong>and</strong> crash intonets, boats, pier walls <strong>and</strong> each other. As aresult of this struggle, the water turns red withthe blood of the dying dolphins. Sometimes thewhole drive hunt process can take days, withthe animals trapped <strong>and</strong> frightened, their fateunknown to them.Because of growing international scrutiny, <strong>and</strong> thepresence of observers from animal welfare <strong>and</strong>conservation groups documenting the hunts forbroadcast, the dolphins are increasingly killed underthe cover of tarpaulins or out of view in othercoastal areas. 8 Access to the areas where thedolphins are slaughtered is obstructed. In Taiji, signsprohibiting photography <strong>and</strong> access to coastalroutes that were once public park areas have beenerected by the fishing cooperative, warning of fallingrocks <strong>and</strong> other pretences to prevent the publicfrom viewing the killing of dolphins. At Futo in2004, fishermen, local police <strong>and</strong> Fisheries Agencyofficials tried to prevent the taking of video <strong>and</strong>photographs <strong>and</strong> a tent was pitched to conceal thekilling. Roads to the harbour where the dolphinswere being held during the hunt were also blockedwith “no admittance” signs. 9 These tents, ortarpaulins, are now used as a st<strong>and</strong>ard part of thehunt to conceal the selection <strong>and</strong> slaughter process.Photos: Michelle Grady/WDCS. There are signs at many vantagepoints along the coast at Taiji, blocking public pathways to the baywhere the dolphins are herded <strong>and</strong> held for slaughter <strong>and</strong> by theslaughter shed.

10The hunts todayJapanese fishermen have conducted drive huntssince the 15th Century. Reductions in dolphinabundance, the introduction of quotas <strong>and</strong> widerpolitical <strong>and</strong> economic factors have all influencedthe hunts, which initially operated over a widegeographic range <strong>and</strong> involved a large number ofhunting teams. 10 <strong>By</strong> the mid-1900s, there werefewer fishing cooperatives still hunting dolphinsbut these surviving hunts exp<strong>and</strong>ed during WorldWar II <strong>and</strong> the post-war period, likely as a resultof fishing operations moving closer to shoreduring wartime <strong>and</strong> post-war food shortages. Thisexpansion was, however, followed by a decline inthe number of drive hunt teams <strong>and</strong> a change inthe species targeted. 11In recent years, the use of radios, mobile phones<strong>and</strong> faster boats has enabled the surviving huntingteams to become even more efficient in theirhunting efforts. This has resulted in an overexploitationof the populations targeted <strong>and</strong>,ultimately, a decline in annual catches. In 1982, theIWC expressed severe concerns about theoverexploitation of the Japanese coastal populationof striped dolphins, the main species targeted. 12Later, in 1992, the IWC's Scientific Committee“strongly advised” that the Government of Japanimplement an “interim halt in all direct catches ofstriped dolphins.” 13 As populations have declined <strong>and</strong>striped dolphin catches plummeted, the huntershave successfully exp<strong>and</strong>ed their hunts to includeother species, including bottlenose dolphins, spotteddolphins, Risso's dolphins <strong>and</strong> false killer whales. 14Currently, drive hunts are conducted at Futo, inShizuoka Prefecture <strong>and</strong> Taiji, in WakayamaPrefecture, (see map). The hunting season in FutoPhoto: Michelle Grady/WDCS. Taiji harbour <strong>and</strong> the buildings usedfor slaughter.runs from September 1 to March 31 of thefollowing year. The hunt in Taiji runs fromOctober 1 to April 30 of the following year,although only pilot whales are targeted afterFebruary. 15 It should be noted that althoughspecies-specific catch quotas are issued for thesehunts, there was little monitoring or enforcementof these quotas by the national Fisheries Agencywhich sets the quotas or the regional prefecturesthat permit the hunts to be carried out, untilprotests by non-governmental environmentalorganizations against the hunts. 16 In 2002, amonitoring <strong>and</strong> penalty system was officiallyintroduced to drive fishermen in Futo but it doesnot involve independent observers. 17Furthermore, there are no restrictions on thekilling methods that are used in these hunts. 18Japan's Fisheries Agency only advises fishermen toreduce the time to death of the animals by cuttingthe spinal cord instead of the throat. 19Map: Futo <strong>and</strong> Taiji are the only Japanese towns currentlyhunting dolphins using drive hunts. Until relatively recently,Katsumoto also carried out drive hunts for dolphins.Pacific OceanKatsumoto, Nagasaki PrefectureFuto, Shizuoka PrefectureTaiji, Wakayama Prefecture

11The hunts todayShizuoka PrefectureDrive hunts began in Shizuoka Prefecture in the17th Century, mainly off the coast of the IzuPeninsula. 20 After World War II, five towns in thisPrefecture still conducted drive hunts, almostexclusively for striped dolphins. In the 1950s,declines in striped dolphins were first witnessed<strong>and</strong>, as a result, a licensing system wasimplemented that restricted the number ofhunting teams <strong>and</strong> limited the hunting season toSeptember to March. 21 <strong>By</strong> the late 1960s, onlytwo locations in Shizuoka Prefecture (Kawana <strong>and</strong>Futo) were permitted to drive <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> dolphins.Kawana conducted its final drive in 1983, leavingFuto as the only town in the Prefectureconducting drive hunts in its coastal waters. 22 Inspite of increased regulation of the drive hunts, itwas not until 1993 that the first catch limits wereimposed. 23Shizuoka Prefecture operates under a quota of600 dolphins a year, consisting of 455 spotteddolphins, 75 bottlenose dolphins <strong>and</strong> 70 stripeddolphins. 24 In spite of this, Futo suspended drivehunting after 1999, perhaps as a result of thedecline of the industry. However, evidently inresponse to persistent dem<strong>and</strong>s from theaquarium industry 25 , Futo conducted its first drivehunt in five years on November 11, 2004, drivingover 100 bottlenose dolphins into Futo harbour. 26Fourteen dolphins were selected by six differentaquaria <strong>and</strong> five were slaughtered <strong>and</strong> used for“research” purposes <strong>and</strong> human consumption. Atleast four other dolphins died of suffocation orshock, <strong>and</strong> the surviving dolphins were reportedlyreleased, one having been fitted with a radiotransmitter. 27 As many of these dolphins werereleased with serious injuries, their continuedsurvival was severely compromised <strong>and</strong> reportssuggest that bodies were recovered from theharbour during the night of the release. 28 It isanticipated that future hunts will occur in Futowith the aim of supplying dolphins for theaquarium industry. A November 2004 article inthe Izu Shimbun newspaper quoted the managerof the Futo Branch of the Ito City FishingCooperative as saying: “I'm glad we were able tohave the hunt. I think it was a good experience forthe fishermen… This year isn't the end, so I'd like tothink about the future.” 29 The revitalization of theFuto hunt to meet the dem<strong>and</strong>s of the aquariumindustry is an unfortunate turnaround for a townthat was becoming better known for its dolphinwatching opportunities than its hunting.Wakayama PrefectureDrive hunts in Wakayama Prefecture did not fullybegin until 1969, with the driving of short-finnedpilot whales at Taiji. The hunt exp<strong>and</strong>ed in 1973 toinclude striped dolphins. Following declines instriped dolphins in the 1980s, Taiji fishermenturned their attention to other species such asbottlenose, spotted <strong>and</strong> Risso´s dolphins. 30 In1993, a limited season (October to April) wasimposed on Taiji's drive hunts, with an annualcatch quota of 2,380 animals. This includes 450striped dolphins, 890 bottlenose dolphins, 400spotted dolphins, 300 Risso's dolphins, 300 shortfinnedpilot whales <strong>and</strong> 40 false killer whales. 31 InTaiji's 2003-2004 drive hunt season, 1,165 dolphinswere killed <strong>and</strong> 78 captured alive for the aquariumtrade. 32 In 2000, 2,009 dolphins were killed <strong>and</strong> 68were captured alive; in 2001, 1,191 dolphins werekilled <strong>and</strong> 28 were captured alive; <strong>and</strong>, in 2002,1,935 dolphins were killed <strong>and</strong> 73 were capturedalive. 33 In spite of concerns raised about thepossible impact on the populations targeted 34 , theoverall numbers taken remain high, with increasingnumbers of animals taken alive.Nagasaki PrefectureUntil relatively recently, drive hunts were alsocarried out in the village of Katsumoto, Iki Isl<strong>and</strong>,Nagasaki Prefecture, starting in 1910. Between1976 <strong>and</strong> 1982, 4,141 bottlenose dolphins, 466Pacific white-sided dolphins, 953 false killerwhales <strong>and</strong> 525 Risso's dolphins were killed. 35 Therelease of video footage of the Iki Isl<strong>and</strong> hunts inthe 1980s resulted in an international outcry overthe killings. Whether this had an impact onbringing about an end to the hunts is difficult toassess, although environmentalist <strong>and</strong> broadcasterHardy Jones, who has been documenting thehunts for several decades, believes publicbroadcast of them brought about an end to the IkiIsl<strong>and</strong> hunts. 36 Katsumoto residents report achange in attitude away from the dolphins aspests as the primary factor in ending the hunts. 37Large catches at Katsumoto ceased around 1986,although the town maintained an annual quota of50 until 1995 38 <strong>and</strong> investigations by a Japanesenon-governmental organization, the Elsa NatureConservancy, revealed that 20 dolphins werecaptured alive in 1996. 39 No drive has beenrecorded or reported since then. However,recent interviews with fisheries cooperativeofficials in Katsumoto indicate interest in resumingthe drive hunts in order to capture live dolphinsfor the aquarium industry. 40

Why the hunts continueWhy the huntscontinue12Photo: Sakae Hemmi. © Elsa Nature Conservancy 2006. These false killer whales <strong>and</strong> bottlenose dolphin are transported alive to the nearby slaughterhouse.

13Why the hunts continue<strong>Dem<strong>and</strong></strong> for dolphin meatFollowing the establishment of a globalmoratorium on commercial whaling in 1986,prices for dolphin meat increased in Japan, 41suggesting a rising dem<strong>and</strong> as the availability ofmeat from large whales declined. Although Japanresumed whaling in 1987 in defiance of themoratorium <strong>and</strong> kills up to 1,000 minke whaleseach year under its so-called “scientific whaling”programme (along with well over 100 otherwhales, including Bryde's, sei <strong>and</strong> spermwhales) 42 , there is evidence that lower pricedolphin meat still replaces or supplements themeat from these larger whales in themarketplace. 43Evidence suggests that consumer dem<strong>and</strong> forcetacean products in Japan is decreasing 44 , even aslarger numbers of whales are hunted annually.While the local consumption of dolphin meatcontinues, mainly in fishing communities, reportssuggest that cetacean meat is not essential to“culinary culture” as the Japanese governmentclaims. 45 Reports suggest that young people rarelyeat dolphin meat, <strong>and</strong> even some Futo fishermencomment that it is no longer necessary. 46However, in an attempt to stimulate dem<strong>and</strong> forthous<strong>and</strong>s of tonnes of whale products from itsscientific whaling programmes, the governmenthas recently started to promote <strong>and</strong> subsidize thesale of whale meat to schools <strong>and</strong> hospitals. 47Photos: Top: <strong>Dolphin</strong> entrails <strong>and</strong> other parts serve as vivid evidence of a recent hunt. Bottom: A victim of the hunt.

14Why the hunts continueMislabelled <strong>and</strong> contaminatedmeatIn 1999, two independent Japanesetoxicologists 48 , working with Americangeneticists, tested samples of raw, cooked <strong>and</strong>canned cetacean meat, blubber <strong>and</strong> organs onsale across Japan, to determine whatcontaminants they contained <strong>and</strong> what speciesthey came from. They found that more thanone quarter of the samples identified usingDNA techniques were mislabelled - i.e. theycontained the DNA of species other than, or inaddition to, the one advertised. 75% of thesemis-advertised products contained at least onepollutant type at a level above regulatory limitsset for human food by national <strong>and</strong> internationalauthorities. Nearly all the mislabelled samplescontained tissues from dolphins, which aretypically amongst the most highly contaminatedof all marine species, living at the top of thefood chain <strong>and</strong> therefore accumulating thehighest level of contaminants in their tissues. 49Japan's Ministry of Health, Labour <strong>and</strong> Welfareconducted its own tests of five cetacean species<strong>and</strong>, as expected, the results published in 2002identified similar levels of contamination tothose found in 1999 <strong>and</strong> subsequently. 50 In aseparate study, the government also identified aproblem with the mislabelling of whale meat. 51Despite this, the government has actuallyincreased the amount of whale meat enteringthe market place since 2000 52 , promoted itsconsumption 53 , <strong>and</strong> even subsidized its sale toschool lunch programmes. 54Recent market analyses continue to findexceedingly high levels of mercury in whale <strong>and</strong>dolphin meat for sale in supermarket chainsthroughout Japan. 55 Studies published in 2005 thattested samples of products from 10 species ofsmall cetacean intended for human consumptionrevealed the mercury concentrations againexceeded the government permitted level. Thehighest concentration of methyl mercury wasfound in a striped dolphin <strong>and</strong> was found to be 87times higher than the permitted level. 56 While theJapanese government has issued specific advice topregnant women about limited consumption ofsmall cetacean meat, the toxicologistsrecommended the advice be urgently revised. 57Competition with fishermenThe Japanese Government claims that dolphins<strong>and</strong> other cetaceans compete with fishermen formarine resources such as fish <strong>and</strong> squid <strong>and</strong> mustbe “culled” to preserve human livelihoods <strong>and</strong>food security. 58 The Nagasaki Prefectureinstigated government-issued 'bounties' for cullingdolphins in the 1970s <strong>and</strong> 1980s. According to theKatsumoto Fishing Cooperative in Katsumoto,Nagasaki, they did not kill dolphins for humanconsumption, but to get rid of nuisance animals. 59Taiji fishermen are also reported to have claimedthe drive hunts to be a form of “pest control”. 60The Government of Japan also uses “predatorcontrol” as a justification for its two “scientificwhaling” programmes; examining the stomachcontents of hundreds of whales to determinetheir impact on fish resources. Despite thecompelling simplicity of the argument that cullinglarge predators will save their smaller prey,fisheries experts find no evidence that marinemammals are to blame for the crisis the world'sfisheries are facing today, or that the long historyof mismanagement of fisheries could be solved byreducing marine mammal populations. 61Additionally, it is possible to determine diet fromnon-lethal research techniques, such as faecalanalysis, by which scientists can determinethrough genetic testing what prey the whaleshave eaten <strong>and</strong> even what intestinal parasites theycarry. 62Photo: Michelle Grady/WDCS. Taiji <strong>Whale</strong> Museum. <strong>Whale</strong> meat issold at the shop here, along with toys <strong>and</strong> stationery depicting cutewhale <strong>and</strong> dolphin imagery. This illustrates the inconsistencies inTaiji between whale <strong>and</strong> dolphin appreciation <strong>and</strong> slaughter.

15Why the hunts continuePhoto: Michelle Grady/WDCS. A bottlenose dolphin taken in one of Taiji's drive hunts leaps in a pen at <strong>Dolphin</strong> Base.The captivity connectionWDCS believes that neither the dem<strong>and</strong> fordolphin meat nor “pest control” can explain thepersistence of drive hunts in Japan today. In fact,evidence suggests that it is the dem<strong>and</strong> for livedolphins from a growing number of marine parks<strong>and</strong> aquaria that is now underpinning the continuedslaughter of dolphins in Japan's drive hunts.There are currently more than 40 commercialaquaria in Japan displaying captive cetaceans. 63Over the years, authors have pointed out thatmany of the cetaceans in Japan's oceanariums hadbeen taken from drive hunts. 64 Six aquariaobtained dolphins from the November 2004 drivehunt in Futo 65 <strong>and</strong> representatives of animalprotection group, One Voice, witnessed whatappeared to be trainers from <strong>Dolphin</strong> Base, theTaiji <strong>Whale</strong> Museum <strong>and</strong> other aquaria selectingdolphins from a 2004 Taiji drive hunt. 66Bottlenose dolphins are the most popular speciesfor display in captivity <strong>and</strong> the numbers of liveindividuals of this species captured in the drivehunts over the years has increased greatly.Historically, between 1968 <strong>and</strong> 1972, Japaneseaquaria purchased 77 live-caught bottlenosedolphins from the drive hunts. This increased to atotal of 181 dolphins between 1973 <strong>and</strong> 1976,<strong>and</strong> 264 individuals between 1977 <strong>and</strong> 1980. 67Between 1973 <strong>and</strong> 1982, Japanese aquariaobtained as many as 532 bottlenose dolphins, 103Pacific white-sided dolphins, 74 short-finned pilotwhales, 35 Risso’s dolphins, nine orcas <strong>and</strong> threefalse killer whales from drive hunts. 68 Live-capturedata were not reported to the InternationalWhaling Commission (IWC) until 1986. Between1986 <strong>and</strong> 1999, 834 small cetaceans werecaptured alive in Japanese waters, including eightfinless porpoises, 569 bottlenose dolphins, sixpilot whales, 116 false killer whales, one commonor 'harbour' porpoise, 40 Risso’s dolphins, sixspotted dolphins, two Dall's porpoises, 17 stripeddolphins, 50 Pacific white-sided dolphins, 17unspecified Delphinidae <strong>and</strong> two unspecifiedKogia. 69 Data from 1999 onwards are not readilyavailable since Japan stopped reporting details oflive captures to the IWC in 2001. 70In 1996, a dead dolphin could be sold for aroundUS $300 each while live bottlenose dolphinsfetched about US $3,000 <strong>and</strong> false killer whalesbetween US $5,000 <strong>and</strong> $6,000. 71 Prices rosesharply in the late 1990s <strong>and</strong> by 1999 Japaneseaquaria were paying as much as US $30,000 for asingle bottlenose dolphin, once trained, 72 whiledead dolphins were selling for only around US$400. 73 Reports suggest the dolphins captured inthe 2004 Futo hunt were purchased by aquariafor between US $3,300 <strong>and</strong> US $3,500 each. 74These figures are said to be much lower thanthose at Taiji where the Fishing Cooperative hasreportedly sold dolphins to aquaria for around US$6,200. 75 Prices paid for dolphins by the aquariumindustry in other parts of the world are muchhigher, with figures of over US $100,000commonly quoted. 76 Nevertheless, consideringthe high prices to be gained for the supply of liveanimals to the captivity industry compared withthe value of dolphin meat, it is reasonable toconclude that payments by the aquarium industryfor live animals provide a strong financial incentiveto continue the hunts. Furthermore, as the pricespaid for dolphins in other parts of the worldcontinue to increase, Japan's drive hunts provide arelatively cheap source of animals for display.

16Why the hunts continueDrive hunts: A dying practice?There are indications that the drive hunts werebecoming a dying practice before the lucrativetrade in live animals really took hold. Of theJapanese towns maintaining the practice, onlyTaiji has continued aggressively with the hunt inrecent years. Katsumoto, on Iki Isl<strong>and</strong>,essentially ab<strong>and</strong>oned the hunts in the late1980s, but has recently indicated it mightreopen them in order to capture livedolphins. 77 In Futo, between 1999 <strong>and</strong> 2004, nohunts took place. In 2001, the Ito City FishingCooperative's Futo Branch had 500 membersbut only about 15 had experience of using theirboats to drive dolphins in a hunt. Thesefishermen were fast reaching retirement age<strong>and</strong> finding it very difficult to find youngerfishermen to carry on the practice. 78Prior to the hunts being ab<strong>and</strong>oned, reportssuggest the work of these fishermen wasproving increasingly difficult. To deflectattention away from the drive hunts, Japan'sFisheries Agency directed the Futo fishermento conceal the 'unsavoury' aspects of the huntsfrom public view, requiring them to screen offFuto's harbour where the dolphins were beingkilled or to kill the dolphins offshore. 79 Reportssuggest both requirements would have madethe hunts unprofitable <strong>and</strong> in the latter casewould have endangered the fishermen's lives. 80Furthermore, after 1999, it was considered tooexpensive to send out 'spotter' boats to lookfor dolphins so the hunts could only beconducted opportunistically when dolphinswere seen from a fishing boat already out atsea, or if they passed within sight of shore.Before the revival of the hunts in 2004, fuelledby the dem<strong>and</strong> for live captures, all thesefactors resulted in a reduction in hunting to thepoint of ab<strong>and</strong>onment. 81 In Taiji, the trend issimilar. Of the 550 members of the Taiji FishingCooperative, only 26 maintain the right to huntdolphins, <strong>and</strong> only 13 boats have a license toconduct the hunts. 82 In addition, the price ofdolphin meat has also significantly dropped inrecent years, possibly due to an increase inlarge whale meat from the exp<strong>and</strong>ed scientificwhaling programme, 83 but also perhaps due tofears over adverse human health effects.There is more evidence that demonstrates theincreased focus of the drive hunts on obtaininglive animals for display by the aquarium industry.A memo circulated by Japan's CetaceanConference on Zoological Gardens <strong>and</strong>Aquariums in August 2005 <strong>and</strong> written by theconference's Executive Secretary asked aquariumdirectors to complete a questionnaire todetermine the extent to which aquaria want todisplay Pacific white-sided dolphins, a species notcurrently targeted by drive hunts, so the resultscould be used to justify a permit application fortheir capture at Taiji. 84 The memo also referred tothe need for discussion between fishermen <strong>and</strong>aquaria to only capture dolphins wanted forcaptivity. Taiji's plans to exp<strong>and</strong> its use of smallcetaceans, a five-year “Community DevelopmentPlan by <strong>Whale</strong> People using <strong>Whale</strong>s”, has beenapproved by the Japanese Government underJapan's Local Revitalisation Law, which enteredinto force in April 2005. 85Photo courtesy of Elsa Nature Conservancy. A dolphin leaps in aholding pen in Taiji.Photo: Michelle Grady/WDCS. At Iruka (dolphin) Park, a facility run bythe Katsumoto Fishing Cooperative, a trainer comm<strong>and</strong>s a dolphinacquired through the drive hunts.

Cooperation unveiledCooperationunveiledPhoto: Michelle Grady/WDCS. This orca, acquired in a drive hunt, performs three times a day at the Taiji <strong>Whale</strong> Museum.17

18Cooperation unveiledThe following case studies illustrate howaquarium industry dem<strong>and</strong>s provide an importantincentive for the continuation of Japan's drivehunts.Futo, 1996In October 1996, over 200 bottlenose dolphins <strong>and</strong>approximately 50 false killer whales were driveninto Futo's harbour. Ten Japanese aquaria fromShizuoka <strong>and</strong> other nearby prefectures werereported to be involved in the capture, althoughonly six selected dolphins for display at theirpremises. Twenty-six bottlenose dolphins <strong>and</strong> sixfalse killer whales were taken into captivity <strong>and</strong>,following selection, 69 bottlenose dolphins <strong>and</strong> fivefalse killer whales were reported killed, althoughthe actual mortality rate is likely to be much higheras a result of stress <strong>and</strong> injury to the animals. 86These removals violated the official quota of 75bottlenose dolphins <strong>and</strong> zero false killer whales forthat drive hunt season. The hunt promptedprotests at the removals by Japanese citizen groups<strong>and</strong> individuals <strong>and</strong> international animal protectionorganizations. 87 Using video footage provided byJapanese group Iruka <strong>and</strong> Kujira (<strong>Dolphin</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>Whale</strong>) Action Network (IKAN), the illegality of thehunt was revealed <strong>and</strong> the national FisheriesAgency ordered the local fishing cooperative torelease the remaining dolphins <strong>and</strong> false killerwhales held in the harbour. 88 Ten days after thehunt, the six false killer whales that had been takeninto captivity were also released. 89 The survivalrate of the released whales is unknown, followingthe stressful hunt, round-up, selection <strong>and</strong>confinement process. Furthermore, two monthsafter this hunt, further quota violations werereported, including information that 22 false killerwhales had been caught <strong>and</strong> sold for 6.6 millionyen (almost US $60,000). 90 Reports suggest thisfigure also includes several other false killer whaleskilled <strong>and</strong> sold for meat. 91Taiji, 1997In 1991, Japan's Fisheries Agency issued anotification to prohibit orca (killer whale) capturesin Japanese coastal waters, with an exemption forscientific research. In 1992, a permit to capture upto five orcas was given for this purpose. InFebruary 1997, there were reports that ten orcaswere driven into Hatajiri Bay, Taiji. Five were soldto three Japanese aquaria, including the Taiji <strong>Whale</strong>Museum <strong>and</strong> Izu Mito Sea Paradise. Five werereleased, their survival status unknown. 92 TwentyJapanese organizations objected to the orcacapture in addition to over 100 internationalenvironmental <strong>and</strong> animal protectionorganizations. 93 <strong>By</strong> June 1997, two of the orcastaken into captivity had already died. Only two arealive today. It was only after the drive hunt hadtaken place in 1997 that the Fisheries Agencyconfirmed that the 1992 quota was still current,although no review of the five-year-old permit orits potential impact on the population targeted hadbeen conducted. 94 The public outcry surroundingthe capture was followed by an announcement bythe Fisheries Agency <strong>and</strong> the Japanese Associationof Zoos <strong>and</strong> Aquariums that captures would onlybe made for “academic purposes” <strong>and</strong> not for“entertainment shows”. 95 The annual quota (fiveorcas for scientific research) was also reviewed <strong>and</strong>a decision made to ban future orca captures unlessfurther permit requests were made. 96Futo, 1999In October 1999, nearly 100 bottlenose dolphinswere driven into Futo Harbour. 97 Reports allegethat representatives from two Japanese aquaria(Aburatsubo Marine Park <strong>and</strong> Izu Mito Sea Paradise)selected six dolphins for their facilities. 98 Followingselection by the aquaria, fishermen slaughtered 69other dolphins, processing their meat at a nearbyslaughterhouse. During this process, the dolphinswere pulled by hooks, lassoed by their flukes withropes, hauled from the water while they were, inmost cases, still alive <strong>and</strong> transported to theprocessing stations. 99 The remaining dolphins wereseriously harmed as they were violently forcedoutside the nets. 100 Footage of this hunt was shownon CNN news in the USA <strong>and</strong> was later describedin a UK government report to the InternationalWhaling Commission. Following internationaldissemination of the hunt footage, drive hunt fishingcooperatives were directed to alter their killingmethods 101 <strong>and</strong> conceal their hunts. 102Photo: Michelle Grady/WDCS. Amphitheatre <strong>and</strong> concrete pools,Taiji <strong>Whale</strong> Museum.

19Cooperation unveiledTaiji, 2004In January 2004, it was reported that over 100bottlenose dolphins were driven into shore inTaiji. According to official records, 23 dolphinswere sold alive, four were killed, <strong>and</strong> 70 werereleased. 104 The hunt appears to have takenplace primarily to provide dolphins for display incaptivity. Japanese aquaria reportedly involved inthe hunt included the Taiji <strong>Whale</strong> Museum <strong>and</strong><strong>Dolphin</strong> Base. 105 In what appeared to be totaldisregard for the welfare of the dolphins held forseveral days, trainers <strong>and</strong> other aquariarepresentatives were seen wading into thechurning waters where dolphins struggled tofree themselves. Several dolphins becameentangled <strong>and</strong> subsequently suffocated in thenets alongside trainers who did not intervene toassist them. 106Photo: Michelle Grady/ WDCS. The ageing dolphin pools at the Taiji <strong>Whale</strong> Museum.Photo: Michelle Grady/WDCS: World <strong>Dolphin</strong> Resort, Taiji. This basic facility contains two large concrete tanks with glass sides, for the public towatch the dolphins swimming.

International trade in drive hunt dolphinsInternationaltrade20Photo: Sakae Hemmi. © Elsa Nature Conservancy 2006. <strong>Dolphin</strong>s being selected for sale to aquaria during a drive hunt in Futo. Aquarium staff confine a dolphinin a sling to raise it onto a truck by crane.

21International trade in drive hunt dolphinsThere is no recognized inventory of informationdocumenting the source of dolphins displayed inaquaria around the world. This makes it difficultto track the destination of dolphins captured alivein drive hunts. The following information iscompiled from newspaper reports, the UnitedStates Marine Mammal Inventory Report, World<strong>Conservation</strong> Monitoring Centre trade data <strong>and</strong>anecdotal reports.United StatesFollowing the making of the American movie“Flipper” in the early 1960s, <strong>and</strong> the very successfultelevision series that followed, dem<strong>and</strong> forcaptive cetaceans increased dramatically. <strong>By</strong> the1970s, the United States had become the mostsignificant source of live cetaceans for the internationalaquarium industry. More than 500 bottlenosedolphins were captured alive in the southeasternUnited States alone between 1973 <strong>and</strong>1988. 107In 1972, partly in response to concerns about thesustainability of these removals, the US governmentadopted the Marine Mammal Protection Act(MMPA), which prohibits, except by a specialpermit, the taking of any marine mammal in USwaters. The introduction of this regulation madeit increasingly difficult for US aquaria to obtainwild-caught animals for public display from USwaters. There is evidence to suggest that someturned to Japan <strong>and</strong> the ready supply of smallwhales <strong>and</strong> dolphins from its drive hunts.The US Marine Mammal Inventory Report(MMIR) records the Miami Seaquarium, Sea LifePark in Hawaii, the Indianapolis Zoo, Sea WorldInc <strong>and</strong> the US Navy as having imported livecetaceans from Japan. 108 No cetaceans capturedin Japan are known to have been imported intothe US since 1993 when the US National MarineFisheries Service denied Marine World Africa USAa permit to import four false killer whales fromJapan, expressing “serious concerns whether thecollection/take of animals through a drive fisheryoperation is [was] humane”. 109It is difficult to obtain details of all the cetaceanscaptured in drive hunts that have been exportedfrom Japan to overseas aquarium facilities. Japanreported the export of 117 live cetaceans(including 16 Pacific white-sided dolphins, 48 falsekiller whales <strong>and</strong> 53 bottlenose dolphins) to theWorld <strong>Conservation</strong> Monitoring Centre (WCMC)between 1972 <strong>and</strong> 2002 to Hong Kong, Republicof Korea, the United States, Israel, Thail<strong>and</strong>,China <strong>and</strong> Mexico. These figures may well beunderestimates. For example, China reported theimport of 26 bottlenose dolphins from Japanbetween 1998 <strong>and</strong> 2002, whereas Japan reportsthe export of only nine bottlenose dolphins toChina in this same period. 110ChinaChina reported imports from Japan of twocommon dolphins in 1995, six false killer whalesbetween 1998 <strong>and</strong> 1999 <strong>and</strong> 46 bottlenosedolphins between 1995 <strong>and</strong> 2003. Japan reportedonly a fraction of this trade to China: six falsekiller whales between 1998 <strong>and</strong> 1999 <strong>and</strong> 26bottlenose dolphins between 1995 <strong>and</strong> 2003 111 ,demonstrating inconsistencies in the reporting ofdata by the two countries. According to datacompiled at the request of a July 2002 workshopin the Philippines sponsored by the Conventionon Migratory Species, there are at least 20 aquariadisplaying captive cetaceans in China, with at leastseven displaying animals imported from Japan,reportedly captured in drive hunts. 112Beijing Aquarium. The Beijing aquarium openedin March 1999 with three false killer whales,seven bottlenose dolphins <strong>and</strong> eight sea lions.Within a month, however, five more false killerwhales <strong>and</strong> five bottlenose dolphins wereimported for display. All 20 cetaceans reportedlycame from the drive hunt in Taiji. 113 In 2001, fiveof the false killer whales were re-exported toSubic Bay, Philippines for display at the OceanAdventures marine park. 114Sunasia Ocean World, Dalien. The Taiji <strong>Whale</strong>Museum exported eight bottlenose dolphinsthought to have been originally captured in drivehunts to this facility in China in June 2005. Thisexport was part of a new scheme initiated by thetown of Taiji to sell dolphins abroad to “promoteinternational, academic <strong>and</strong> scientific exchange.” 115Ocean Park, Hong Kong. A 1994 scientific studyon the survivorship of cetaceans at Ocean Parkbetween 1974 <strong>and</strong> 1994 reported that it acquiredat least five short-finned pilot whales, 19 falsekiller whales, 15 Pacific white-sided dolphins <strong>and</strong>up to 50 bottlenose dolphins from Iki Isl<strong>and</strong> orTaiji, Japan. 116 Eleven false killer whales wereimported by Ocean Park in 1987 alone 117 , the lastof these animals dying in 1999. 118

22International trade in drive hunt dolphinsPhoto: Michelle Grady/WDCS. In the bay at Taiji are training pens belonging to <strong>Dolphin</strong> Base. <strong>Dolphin</strong> Base has an active training programme <strong>and</strong>reports suggest it provides dolphins <strong>and</strong> training resources to aquaria throughout Japan <strong>and</strong> overseas. 103TaiwanHualien Ocean World. Hualien Ocean World,which opened in October 2002 with 11bottlenose dolphins that were captured at Taiji, 119imported a total of 17 dolphins from Japanbetween 2002 <strong>and</strong> 2005. 120Republic of Korea (South Korea)According to WCMC data, the Republic of Koreaimported four false killer whales from Japan in1983 <strong>and</strong> three Pacific white-sided dolphins in1985. WCMC data also records the export of 17bottlenose dolphins to the Republic of Koreabetween 1983 <strong>and</strong> 1991 <strong>and</strong> a further two tradedfrom Japan to Korea between 1997 <strong>and</strong> 1998. 121PhilippinesIn January 2001, the Subic Bay MarineExploratorium opened in the Philippines with fivefalse killer whales transferred from the BeijingAquarium in China. 122 The facility offers visitorsthe opportunity to swim with these animals,which were thought to have been originallycaptured in Japanese drive hunts. 123 The marinepark, run by Ocean Adventures, remained opendespite a cease-<strong>and</strong>-desist order from theDepartment of the Environment <strong>and</strong> NaturalResources in March 2001, prohibiting continuedactivity at the marine park due to it having notobtained an environmental compliance certificateto operate. 124 Four bottlenose dolphins werereportedly exported by Japan to this facility fromthe January 2004 drive hunt in Taiji. 125 Since 2001,three false killer whales have died at theExploratorium. 126 In August 2005, the PhilippinesDepartment of Environment <strong>and</strong> NaturalResources closed the Exploratorium indefinitelyto review “allegations that the park violated lawsagainst maltreatment <strong>and</strong> abuse of whales.” 127PalauThe tiny isl<strong>and</strong> of Palau is situated in the PacificOcean to the north of Indonesia. In January 2002,<strong>Dolphin</strong> Bay, owned by <strong>Dolphin</strong>s Pacific, openedin Palau. The facility, displaying 11 dolphins, offersinteraction programmes such as swimming withdolphins <strong>and</strong> dolphin-assisted therapy. 128 Reportssuggest the animals were exported from Japan<strong>and</strong> were captured in drive hunts. 129Photo: A dolphin lies in the shallows awaiting its fate .

The role of international zoo <strong>and</strong> aquarium organizationsZoo <strong>and</strong> aquariumorganizationsPhoto: These bottlenose dolphins struggle as they are trapped by boats during a round-up in Futo.23

24The role of international zoo <strong>and</strong> aquarium organizationsSome aquaria that have featured performingwhales <strong>and</strong> dolphins imported from Japan are alsomembers of professional international zoologicalassociations. The American Zoo <strong>and</strong> AquariumAssociation (AZA) lists among its members all USSea World Parks <strong>and</strong> Ocean Park Hong Kong, thelatter also being part of the South East Asia Zoo<strong>and</strong> Aquarium Association (SEAZA). 130 The AZA,SEAZA <strong>and</strong> the Japanese Association of Zoos <strong>and</strong>Aquariums (JAZA) are in turn members to theWorld Association of Zoos <strong>and</strong> Aquariums(WAZA), an umbrella organization whose missionis: “to guide, encourage <strong>and</strong> support the zoos,aquariums, <strong>and</strong> like-minded organisations of theworld in animal care <strong>and</strong> welfare, environmentaleducation <strong>and</strong> global conservation.” 131WDCS believes that the sourcing of dolphinsfrom drive hunts is a violation of the WAZA“Code of Ethics” that recognizes respect for theanimals in its care, opposes “cruel <strong>and</strong> nonselectivemethods of taking animals from the wild”<strong>and</strong> states that “Members must be confident thatsuch acquisitions will not have a deleterious effectupon the wild population.” 132 In October 2005,seemingly in response to increasing pressurefrom environmental organizations <strong>and</strong> concernedscientists, the WAZA issued a statement to itsmembers, reminding them to “ensure that theydo not accept animals obtained by the use ofmethods which are inherently cruel”, <strong>and</strong> notingthat: “the catching of dolphins by the use of amethod known as ‘drive fishing’ is considered anexample of such a non acceptable capturemethod.” 133 It is hoped that this statement will beused to impose sanctions against any WAZAmembers that knowingly procure dolphins fromthe drive hunts.The ‘rescue’ rationaleIn 1993, Marine World Africa USA described its decision to capture four false killer whales from adrive hunt on Iki Isl<strong>and</strong> as a “humane act that saved four animals from certain death.” 134 More recently,in a BBC film documenting the drive hunts, Tim Desmond of Ocean Adventures, Philippines, a facilitydisplaying cetaceans captured in drive hunts stated: “every animal we have here had a life expectancy ofone day…these animals were either going to be taken alive or die.” 135 Desmond's position is reiteratedin his letter to the Subic Bay Management Authority in December 2000, in which he states: “We wentto Japan precisely because these were doomed animals…collection of our animals was a side-product.This was <strong>and</strong> is the lowest impact way to collect wild animals for public display. These are animals thathave already been captured <strong>and</strong> who are literally minutes from death.” 136 It is WDCS’s opinion that this'rescue' rationale to purchase cetaceans captured in drive hunts is misguided <strong>and</strong> belies the large sumsof money paid by aquaria for individual whales <strong>and</strong> dolphins captured alive in the hunts.Photo: This dolphin is sedated after being hauled from a drive hunt on a truck for transport to an aquarium.

Drive hunts: Impact on dolphin welfareDrive hunts:WelfarePhoto: Divers surround a dolphin in the water.25

26Drive hunts: Impact on dolphin welfareIt is a common expectation in modern societythat animals that are slaughtered for food shouldnot be subjected to unnecessary suffering. 137 Theguiding principle for the humane slaughter oflivestock is the achievement of immediateunconsciousness, usually through stunning,followed by a rapid progression to death. 138 As aresult, many countries have legislation requiringmammals to be stunned before slaughter in orderto prevent unnecessary pain <strong>and</strong> suffering duringthe slaughter process. <strong>Dolphin</strong>s, like cows <strong>and</strong>pigs, are mammals. However, the methods usedto chase, capture <strong>and</strong> kill cetaceans do not <strong>and</strong>cannot guarantee instantaneous insensibilityfollowed rapidly by death. 139 As a result, manythous<strong>and</strong>s of dolphins killed each year may sufferextreme pain <strong>and</strong> suffering during slaughter over aprolonged period of time.Chase <strong>and</strong> round-upStress suffered during capture <strong>and</strong> the selectionprocess is likely to compromise the survival of anydolphins released from the hunt. 140 Studies haveshown that the capture of wild cetaceans,regardless of methodology, is liable to induceextreme levels of stress. 141 Chase <strong>and</strong> pursuit mayresult in stress-related mortality in cetaceans,since over-exertion may lead to muscular <strong>and</strong>cardiac tissue damage <strong>and</strong> possibly lead to shock,paralysis <strong>and</strong> death, or longer term morbidity. 142However, no assessment has been made of theeffects of the drive hunt on dolphins, including thelong-term physiological effects on any survivors.Beyond this harmful individual impact, thedisruption or damage to a captured animal's socialgroup caused by its removal, while largelyunknown <strong>and</strong> not well studied, may besubstantial. 143Photo: Sakae Hemmi. © Elsa Nature Conservancy 2006. <strong>Dolphin</strong>sstruggle <strong>and</strong> exhibit signs of distress as they are selected by aquariumrepresentatives in Futo.Capture <strong>and</strong> slaughterIn other cetacean drive hunts, such as those in theFaroe Isl<strong>and</strong>s, a knife is used to cut through theskin, blubber <strong>and</strong> flesh to sever the spinal column<strong>and</strong> the blood supply to the brain in order toinduce loss of sensibility <strong>and</strong> death as a result ofblood loss. 144 In contrast, as recorded in a paperdescribing a video recording of Futo's October1999 drive hunt <strong>and</strong> presented by the UKgovernment to the <strong>Whale</strong> Killing Methods <strong>and</strong>Associated Welfare Issues Working Group at the2000 International Whaling Commission meeting,in Japan it is more common that the dolphins arecut in the 'throat' region, leaving the so-called“spinal rete arteries, which lie in the spinal column<strong>and</strong> supply blood to the brain... intact, so thedolphins remain conscious for an unknown length oftime.” 145 The paper goes on to state that: “Theslaughtermen seemed wary <strong>and</strong> unfamiliar with theslaughter process as in 3 filmed incidents theystopped cutting when the animals reacted violentlyto the severing of a major blood vessel… There is noevidence of any attempt to induce rapid loss ofconsciousness <strong>and</strong> death…Overall the film shows anapparent lack of regulation, training in appropriatemethods <strong>and</strong> techniques <strong>and</strong> care or considerationfor the welfare of these animals. It is clear that thedolphins suffered extreme distress <strong>and</strong> pain <strong>and</strong> thiscannot be considered to be acceptable or humane byany accepted international or national st<strong>and</strong>ards.” 146In August of 2002, it was reported that Futodolphin hunters would use a new, fast-killingmethod to sever the spinal cord just behind theblowhole. This was predicted to kill the animalwithin 30 seconds, down from the currentestimate of 10 minutes. This ‘fast-kill’ method isreported to have been adopted by Taiji fishermenas well. 147 However, this method has not beendocumented by any national or internationalobservers 148 <strong>and</strong> one former dolphin hunter hasclaimed that the method of cutting the spinal cordwould be nearly impossible to employ because itis “extremely difficult <strong>and</strong> dangerous tofishermen.” 149Psychological sufferingSmall cetaceans often live in close, stronglybondedfamily groups. During the killing <strong>and</strong>selection of dolphins in the drive hunts, individualanimals may be swimming in the blood of otherdolphins in their family group, hearing <strong>and</strong> seeingtheir distress as they are killed. Scientific researchreveals that dolphins are self-aware <strong>and</strong> cognitive

27Drive hunts: Impact on dolphin welfarebeings. Bottlenose dolphins have exhibited mirrorself-recognition, an ability shared only by greatapes <strong>and</strong> humans. 150 WDCS believes that thedolphins targeted by these hunts may be aware ofwhat is happening to them <strong>and</strong> other dolphinsduring the process <strong>and</strong> suffer extreme fear <strong>and</strong>distress as a result.Live capture, transport <strong>and</strong> captivityIn 1996, Japanese researcher Sakae Hemmirecorded details of the selection of animals by theaquarium industry during a drive hunt in Futo:“To begin with, two fishing boats confused the dolphinswith sounds, then rounded up the dolphins, which werescattered throughout the port. These two vessels hadmetal bars protruded from their hulls into the water,<strong>and</strong> fishermen banged on them constantly withhammers as other fishermen beat on the sides of theirvessels with wooden mallets, <strong>and</strong> still others slappedthe water over <strong>and</strong> over with long poles, therebyterrorizing the dolphins <strong>and</strong> chasing them around.Then, just as when l<strong>and</strong>ing dolphins for slaughter, threefishing boats spread fishing nets from one vessel to thenext to cut off the dolphins' escape route <strong>and</strong>inexorably herd them towards the wall at pierside.The 30-odd dolphins separated out in this mannerare then sorted according to what the aquariumswant. A person from an aquarium, who appears tobe a leader, st<strong>and</strong>s at the top of the wall pointing atdolphins saying, ‘This one,’ <strong>and</strong> ‘That one,’ as about10 aquarium divers subdue the indicated dolphins<strong>and</strong> measure their length with a long bar. It appearsthey are after animals about 150-200 cm long, <strong>and</strong>do not want any over 250 cm. One or two of thedivers restraining the dolphin then dive under theanimal <strong>and</strong> inspect the underbelly slit to see if it ismale or female. Almost all aquariums prefer females,<strong>and</strong>, as far as records indicate, only one male hasever been taken to an aquarium. Even if all otherrequirements were fulfilled, no dolphins with injurieswere chosen. In addition to being panicked by theloud noises <strong>and</strong> chased by divers, the dolphins getcaught in nets, run into the wall <strong>and</strong> collide violentlywith other dolphins, so many of them have injuries.For this reason it took considerable time to selectdolphins that satisfied the aquariums.Divers hold the chosen dolphins at their sides <strong>and</strong> liftthem onto a special dolphin stretcher, which hasholes for dolphins' pectoral fins, that is lowered intothe water level by a crane. Once a dolphin isproperly ensconced, the crane lifts it onto a truckthat the aquariums have waiting on the pier.Aquarium personnel immediately remove thestretcher, <strong>and</strong> move on to the next operation. Whendolphins are taken to nearby aquariums, theirtransport involves placing them on wet mattresses,covering the upper parts of their bodies with cloth,<strong>and</strong> occasionally wetting them, but whendestinations are far, dolphins are put in long tanks tokeep their bodies immersed. In all cases sedativesare administered to keep the dolphins fromstruggling. On this occasion the sedative caused theshock death of one female; her belly wassubsequently cut open, <strong>and</strong> the meat extracted <strong>and</strong>processed.” 151Photo: These bottlenose dolphins captured during a drive hunt are crudely transported by flatbed truck to awaiting facilities.

28Drive hunts: Impact on dolphin welfareThe live capture <strong>and</strong> transport of these animals isan extremely stressful process that may result inthe deaths of the dolphins before they arrive at theaquarium facility they are chosen for. A study ofbottlenose dolphins captured from the wildindicates a six-fold increase in mortality in their firstfive days of confinement. 152 In the drive hunts, evendolphins released from the selection process mayexperience significant mortality. Furthermore, thesmall cetaceans typically held in captivity, such asbottlenose dolphins <strong>and</strong> orcas, are wholly aquatic,far-ranging, fast-moving, deep-diving predators. Inthe wild they may travel up to 150 kilometres aday, reach speeds of up to fifty kilometres an hour,<strong>and</strong> dive several hundred metres. Small cetaceansare highly intelligent, extraordinarily social, <strong>and</strong>behaviourally complex. 153 WDCS believes that it isimpossible to accommodate their mental, physical<strong>and</strong> social needs in captivity <strong>and</strong> that it is cruel toconfine them. Scientific evidence indicates thatcetaceans in captivity suffer extreme mental <strong>and</strong>physical stress, 154 which is revealed in aggressionbetween themselves <strong>and</strong> towards humans, a lowersurvival rate <strong>and</strong> higher infant mortality than in thewild. 155 In addition, many cetaceans are held inappallingly inadequate conditions that have a directnegative impact on their health <strong>and</strong> wellbeing.Conditions <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ards of carein Japanese aquariaIn October 2005, Hardy Jones of Bluevoice.orgtravelled to Japan to investigate the aquaria thathad acquired bottlenose dolphins captured inthe 2004 Futo drive hunt. Two of them werefound at <strong>Dolphin</strong> Fantasy, Ito City, where theyare held with Ami-Chan 156 , a bottlenosedolphin originally captured at Taiji <strong>and</strong> held at<strong>Dolphin</strong> Fantasy since 1999. The sea pen inwhich they are held is small <strong>and</strong> sits in thepolluted harbour water. Ami-Chan is reportedto have survived five other dolphins at <strong>Dolphin</strong>Fantasy.Another dolphin from the Futo 2004 hunt wasfound in a sea pen at Awashima Marine Park.He had also been held at <strong>Dolphin</strong> Fantasy in Itobefore his transfer to Awashima. 157A female transferred from Futo in January 2005was traced to Shinagawa Aquarium in Tokyo, ina tiny pool under a highway overpass,performing tricks for visitors. 158Photo: Dead <strong>and</strong> dying dolphins by the quayside in Futo

Drive hunts: Detrimental to cetacean conservationDrive hunts:<strong>Conservation</strong>Photo: William Rossiter. Spotted dolphins.29

30Drive hunts: Detrimental to cetacean conservationThe overall impact of Japan's drive hunts on thespecies <strong>and</strong> populations of cetaceans they target isdifficult to determine, due to the lack of biologicaldata available for most species. 159 The striped dolphinhas been the most heavily exploited species. TheIWC has documented a serious decline in coastalpopulations of striped dolphins <strong>and</strong> recent declines incatches of short-finned pilot whales <strong>and</strong> spotteddolphins. 160 In 1992, it expressed its: “…great concernabout the status of the striped dolphin stock exploitedby the drive fishery. It was noted that the catch hasdeclined to 1/10 of the level in the early 1960s <strong>and</strong>fishermen have started exploiting other species in recentyears. The number of vessels operating this fishery hasincreased during the period…<strong>and</strong> in recent years mostschools seen are harvested. This indicates decline inavailability of striped dolphins to the fishery due to thedepletion of the exploited stock.” 161 Japanese scientistshave expressed similar concerns, stating, in 1993:“We conclude that the availability of striped dolphins tothe drive fisheries on the Pacific coast has declined overthe past 30 years <strong>and</strong> the fishery has been forced toswitch to other delphinids. The status of other dolphinstocks is unknown due to uncertainties in stock identity<strong>and</strong> the catch trend.” 162 Many of the populationstargeted by drive hunts are also subject to removalsin Japan's other small cetacean hunts. 163The dem<strong>and</strong> for captive dolphins does far more thanharm the individual captured - it can threatendolphin populations <strong>and</strong> the marine ecosystem. Thecapture of even a few animals can result in the deathor injury of many more dolphins, since the captureactivities involve intensive harassment of a group orgroups. In addition, it negatively impacts on alreadydepleted dolphin populations by removing breeding(or otherwise important) members from the group.The capture <strong>and</strong> removal of dolphins for interactiveprogrammes is especially problematic in this regardbecause female dolphins are preferred for theseprogrammes (females are typically regarded as lessaggressive towards humans than male dolphins).Many studies of wildlife populations havedemonstrated that the removal of females can resultin seriously harmful consequences to animalpopulations over the long term. 164The IUCN Cetacean Specialist Group has noted, inits <strong>Conservation</strong> Action Plan for 2002 to 2010:“Removal of live cetaceans from the wild, for captivedisplay <strong>and</strong>/or research, is equivalent to incidental ordeliberate killing, as the animals brought into captivity(or killed during capture operations) are no longeravailable to help maintain their populations. Whenunmanaged <strong>and</strong> undertaken without a rigorous programof research <strong>and</strong> monitoring, live-capture can become aserious threat to local cetacean populations… As ageneral principle, dolphins should not be captured orremoved from a wild population unless that specificpopulation has been assessed <strong>and</strong> it has beendetermined that a certain amount of culling can beallowed without reducing the population's long-termviability or compromising its role in the ecosystem. Suchan assessment, including delineation of stockboundaries, abundance, reproductive potential,mortality, <strong>and</strong> status (trend) cannot be achieved quicklyor inexpensively, <strong>and</strong> the results should be reviewed byan independent group of scientists before any capturesare made. Responsible operators (at both the capturingend <strong>and</strong> the receiving end) must show a willingness toinvest substantial resources in assuring that proposedremovals are ecologically sustainable.” 165 Thecontinued removal of animals in the drive hunts, agrowing number for the aquarium industry, in theface of evidence demonstrating their detrimentalimpact, shows a complete lack of precaution bythose involved <strong>and</strong> may be severely damaging thesustainability of the populations targeted.Status of species targeted by thedrive huntsFrom the IUCN Red List 166Striped dolphin: “Catches of striped dolphins in Japan havedeclined dramatically since the 1950s, <strong>and</strong> there is clearevidence that this decline is the result of stock depletion byover-hunting. Striped dolphins have been completely or nearlyeliminated from some areas of past occurrence.”Pantropical spotted dolphin: “Pantropical spotteddolphins are subject to high mortality in Japan, where theyare killed by harpooning <strong>and</strong> driving. Catches in Japan havebeen in the thous<strong>and</strong>s in some years, although they havetotaled less than 500 per year over the past decade.”Bottlenose dolphin: “Large numbers have been taken inJapan in the drive <strong>and</strong> harpoon fisheries, including 4,000 atIki Isl<strong>and</strong> from 1977 to 1982. Takes in drive <strong>and</strong> h<strong>and</strong>harpoonfisheries along the Pacific coast have increased sincethe early 1980s.”Risso's dolphin: “Regularly hunted in Japan in catchesranging from about 250-500.”Short-finned pilot whale: “Stocks are ill-defined exceptoff Japan, where two distinct forms have been identified... atleast one of the two forms hunted off Japan is depleted. Thenorthern form, whose population is estimated at only 4000-5000, is subject to small-type whaling with an annualnational quota of 50. The southern form, with an estimatedpopulation of about 14,000 in coastal waters, is subject tosmall-type whaling, h<strong>and</strong>-harpoon whaling, <strong>and</strong> drive whaling,<strong>and</strong> there is an annual national quota of 450.”

National legislation <strong>and</strong> the drive huntsNational legislationIn Japan, all cetaceans are treated <strong>and</strong> regulated as afisheries resource, under the control of the FisheriesAgency. This is in spite of the establishment of theEnvironment Agency in 1971, which gained control ofother wildlife issues in Japan. Japan's Law for the<strong>Conservation</strong> of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna <strong>and</strong>Flora (Species Preservation Law), enacted in 1993, alsoexcludes marine mammals, following a memor<strong>and</strong>um ofunderst<strong>and</strong>ing between the Fisheries <strong>and</strong> EnvironmentAgencies. 167In 1993, the Fisheries Agency established quotas foreight species of small cetacean in each prefectureinvolved in hunting them. Although these quotas werereportedly based on science, they appeared heavilyinfluenced by political factors, with emphasis on pastyields. 168 Japanese government research on smallcetaceans in coastal waters remains data deficient. 169Urgently-needed catch quota reviews for most of thedolphin species targeted by the drive hunts have beenpostponed by the Fisheries Agency, at least partly due tothe lack of information about the status of the animalstargeted by them. 170In 2002, the National Biodiversity Strategy was revised<strong>and</strong> a new paragraph, entitled “The Protection <strong>and</strong>Management of Marine Animals”, added, at the requestof non-governmental conservation <strong>and</strong> welfareorganizations. In spite of this apparent achievement,however, the text currently contains no reference to theimportance of the protection <strong>and</strong> management ofcetaceans for coastal biodiversity. 171 Also in 2002, theLaw for the Protection of Wild Birds <strong>and</strong> Mammals <strong>and</strong>Appropriation of Hunting was revised. Marine mammalswere again excluded from the law. 172The 1973 Law concerning the Protection <strong>and</strong>Management of Animals was revised in 2005 to tightenthe regulations on businesses h<strong>and</strong>ling animals, throughthe introduction of a registration or licensing system. 173As a result of pressure from conservation organizationsthrough the Animal Protection Committee to havebusinesses trading <strong>and</strong> capturing dolphins included, allbusinesses trading in wild animals are subject to thelaw. 174 The impact of this has yet to be realized.Photo: Michelle Grady/WDCS: False killer whale at Iruka Park in Katsumoto.31

In conclusionIn conclusionThe government of Japan allows thous<strong>and</strong>s of smallcetaceans to be killed each year in hunts around thecoast of Japan. <strong>Dolphin</strong>s, porpoises <strong>and</strong> small whaleshave inadequate legal protection under Japanese law toprevent them from being killed in the mostindiscriminate <strong>and</strong> brutal manner. The drive huntsrepresent just one form of these annual hunts.Now, as the dem<strong>and</strong> for live cetaceans has increased overthe last two decades, a growing number of aquaria fromJapan <strong>and</strong> several other countries have sourced livedolphins from Japan's drive hunts. The large sums ofmoney paid for these animals represent an importantfinancial incentive to continue an industry that mightotherwise be in decline. WDCS believes that these huntsmay not survive without the purchase of live cetaceans byan increasing number of aquaria. As a result, the purchaseof live cetaceans by aquaria threatens the survival ofdiscrete populations of small cetaceans <strong>and</strong>, at the sametime, allows unspeakable suffering to be inflicted onindividual animals. With more cetacean meat being madeavailable by Japan's exp<strong>and</strong>ing whaling activities <strong>and</strong> thecontroversy surrounding the high level of contaminants insmall cetacean meat, as reported by Japanese consumersafety organizations such as Safety First 175 <strong>and</strong> theConsumers' Union of Japan 176 , the focus of the huntstoday appears to be increasingly on obtaining live animalsfor display in aquaria. This is not surprising given the highvalue of the live animals.Many aquaria, amusement parks <strong>and</strong> zoos displayingcetaceans claim to play an important role in education<strong>and</strong> conservation. For example, the Alliance of MarineMammal Parks <strong>and</strong> Aquariums (AMMPA) states that itsinternational member facilities are “dedicated to thehighest st<strong>and</strong>ards of care for marine mammals <strong>and</strong> to theirconservation in the wild”. 177 However, a growing numberof aquaria purchase live cetaceans which have beensourced from the drive hunts in Japan. These huntsthreaten the survival of the populations targeted <strong>and</strong>inflict extreme pain <strong>and</strong> suffering on individual animals asthey are killed or captured alive for aquaria.It is time for Japan's drive hunts to end. WDCS callsupon the international zoo <strong>and</strong> aquarium associations toprohibit any members or member institutions fromsourcing live dolphins from these hunts <strong>and</strong> to sanctionany that do.32Photo: Michelle Grady/WDCS: A false killer whale <strong>and</strong> a bottlenose dolphin at Iruka Park in Katsumoto.