John Wallis_0

John Wallis_0

John Wallis_0

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

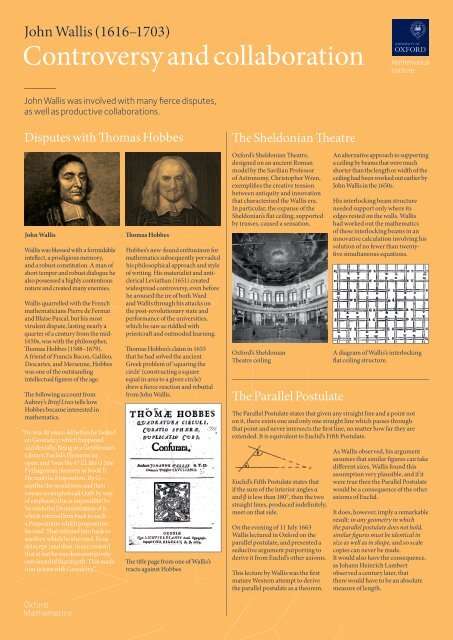

<strong>John</strong> <strong>Wallis</strong> (1616–1703)Controversy and collaboration<strong>John</strong> <strong>Wallis</strong> was involved with many fierce disputes,as well as productive collaborations.Disputes with Thomas HobbesThe Sheldonian Theatre<strong>John</strong> <strong>Wallis</strong><strong>Wallis</strong> was blessed with a formidableintellect, a prodigious memory,and a robust constitution. A man ofshort temper and robust dialogue healso possessed a highly contentiousnature and created many enemies.<strong>Wallis</strong> quarrelled with the Frenchmathematicians Pierre de Fermatand Blaise Pascal, but his mostvirulent dispute, lasting nearly aquarter of a century from the mid-1650s, was with the philosopher,Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679).A friend of Francis Bacon, Galileo,Descartes, and Mersenne, Hobbeswas one of the outstandingintellectual figures of the age.The following account fromAubrey’s Brief Lives tells howHobbes became interested inmathematics.“He was 40 years old before he lookedon Geometry; which happenedaccidentally. Being in a Gentleman’sLibrary, Euclid’s Elements layopen, and ’twas the 47 El. libri I [thePythagorean theorem in Book I].He read the Proposition. By G—,sayd he (he would now and thensweare an emphaticall Oath by wayof emphasis) this is impossible! Sohe reads the Demonstration of it,which referred him back to sucha Proposition; which propositionhe read. That referred him back toanother, which he also read. Et sicdeinceps [and thus, in succession]that at last he was demonstrativelyconvinced of that trueth. This madehim in love with Geometry.”Thomas HobbesHobbes’s new-found enthusiasm formathematics subsequently pervadedhis philosophical approach and styleof writing. His materialist and anticlericalLeviathan (1651) createdwidespread controversy, even beforehe aroused the ire of both Wardand <strong>Wallis</strong> through his attacks onthe post-revolutionary state andperformance of the universities,which he saw as riddled withpriestcraft and outmoded learning.Thomas Hobbes’s claim in 1655that he had solved the ancientGreek problem of ‘squaring thecircle’ (constructing a squareequal in area to a given circle)drew a fierce reaction and rebuttalfrom <strong>John</strong> <strong>Wallis</strong>.The title page from one of <strong>Wallis</strong>’stracts against HobbesOxford’s Sheldonian Theatre, An alternative approach to supportingdesigned on an ancient Roman a ceiling by beams that were muchmodel by the Savilian Professor shorter than the length or width of theof Astronomy, Christopher Wren, ceiling had been worked out earlier byexemplifies the creative tension <strong>John</strong> <strong>Wallis</strong> in the 1650s.between antiquity and innovationthat characterised the <strong>Wallis</strong> era. His interlocking beam structureIn particular, the expanse of the needed support only where itsSheldonian’s flat ceiling, supported edges rested on the walls. <strong>Wallis</strong>by trusses, caused a sensation. had worked out the mathematicsof these interlocking beams in aninnovative calculation involving hissolution of no fewer than twentyfivesimultaneous equations.Oxford’s SheldonianA diagram of <strong>Wallis</strong>’s interlockingTheatre ceilingflat ceiling structure.The Parallel PostulateThe Parallel Postulate states that given any straight line and a point noton it, there exists one and only one straight line which passes throughthat point and never intersects the first line, no matter how far they areextended. It is equivalent to Euclid’s Fifth Postulate.As <strong>Wallis</strong> observed, his argumentassumes that similar figures can takedifferent sizes. <strong>Wallis</strong> found thisassumption very plausible, and if itEuclid’s Fifth Postulate states that were true then the Parallel Postulateif the sum of the interior angles α would be a consequence of the otherand β is less than 180°, then the two axioms of Euclid.straight lines, produced indefinitely,meet on that side.It does, however, imply a remarkableresult: in any geometry in whichOn the evening of 11 July 1663 the parallel postulate does not hold,<strong>Wallis</strong> lectured in Oxford on the similar figures must be identical inparallel postulate, and presented a size as well as in shape, and so scaleseductive argument purporting to copies can never be made.derive it from Euclid’s other axioms. It would also have the consequence,as Johann Heinrich LambertThis lecture by <strong>Wallis</strong> was the first observed a century later, thatmature Western attempt to derive there would have to be an absolutethe parallel postulate as a theorem. measure of length.