No-Till: The Quiet Revolution - Research - Washington State University

No-Till: The Quiet Revolution - Research - Washington State University

No-Till: The Quiet Revolution - Research - Washington State University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

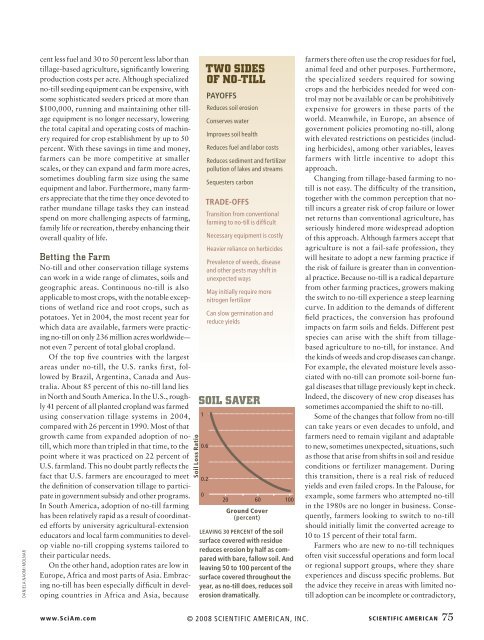

daniela naomi molnarcent less fuel and 30 to 50 percent less labor thantillage-based agriculture, significantly loweringproduction costs per acre. Although specializedno-till seeding equipment can be expensive, withsome sophisticated seeders priced at more than$100,000, running and maintaining other tillageequipment is no longer necessary, loweringthe total capital and operating costs of machineryrequired for crop establishment by up to 50percent. With these savings in time and money,farmers can be more competitive at smallerscales, or they can expand and farm more acres,sometimes doubling farm size using the sameequipment and labor. Furthermore, many farmersappreciate that the time they once devoted torather mundane tillage tasks they can insteadspend on more challenging aspects of farming,family life or recreation, thereby enhancing theiroverall quality of life.Betting the Farm<strong>No</strong>-till and other conservation tillage systemscan work in a wide range of climates, soils andgeographic areas. Continuous no-till is alsoapplicable to most crops, with the notable exceptionsof wetland rice and root crops, such aspotatoes. Yet in 2004, the most recent year forwhich data are available, farmers were practicingno-till on only 236 million acres worldwide—not even 7 percent of total global cropland.Of the top five countries with the largestareas under no-till, the U.S. ranks first, followedby Brazil, Argentina, Canada and Australia.About 85 percent of this no-till land liesin <strong>No</strong>rth and South America. In the U.S., roughly41 percent of all planted cropland was farmedusing conservation tillage systems in 2004,compared with 26 percent in 1990. Most of thatgrowth came from expanded adoption of notill,which more than tripled in that time, to thepoint where it was practiced on 22 percent ofU.S. farmland. This no doubt partly reflects thefact that U.S. farmers are encouraged to meetthe definition of conservation tillage to participatein government subsidy and other programs.In South America, adoption of no-till farminghas been relatively rapid as a result of coordinatedefforts by university agricultural-extensioneducators and local farm communities to developviable no-till cropping systems tailored totheir particular needs.On the other hand, adoption rates are low inEurope, Africa and most parts of Asia. Embracingno-till has been especially difficult in developingcountries in Africa and Asia, becauseSoil Loss RatioTWO SIDESOF NO-TILLPayoffsReduces soil erosionConserves waterImproves soil healthReduces fuel and labor costsReduces sediment and fertilizerpollution of lakes and streamsSequesters carbonTrade-offsTransition from conventionalfarming to no-till is difficultNecessary equipment is costlyHeavier reliance on herbicidesPrevalence of weeds, diseaseand other pests may shift inunexpected waysMay initially require morenitrogen fertilizerCan slow germination andreduce yieldsSoil saver10.60.2020 60 100Ground Cover(percent)Leaving 30 percent of the soilsurface covered with residuereduces erosion by half as comparedwith bare, fallow soil. Andleaving 50 to 100 percent of thesurface covered throughout theyear, as no-till does, reduces soilerosion dramatically.farmers there often use the crop residues for fuel,animal feed and other purposes. Furthermore,the specialized seeders required for sowingcrops and the herbicides needed for weed controlmay not be available or can be prohibitivelyexpensive for growers in these parts of theworld. Meanwhile, in Europe, an absence ofgovernment policies promoting no-till, alongwith elevated restrictions on pesticides (includingherbicides), among other variables, leavesfarmers with little incentive to adopt thisapproach.Changing from tillage-based farming to notillis not easy. <strong>The</strong> difficulty of the transition,together with the common perception that notillincurs a greater risk of crop failure or lowernet returns than conventional agriculture, hasseriously hindered more widespread adoptionof this approach. Although farmers accept thatagriculture is not a fail-safe profession, theywill hesitate to adopt a new farming practice ifthe risk of failure is greater than in conventionalpractice. Because no-till is a radical departurefrom other farming practices, growers makingthe switch to no-till experience a steep learningcurve. In addition to the demands of differentfield practices, the conversion has profoundimpacts on farm soils and fields. Different pestspecies can arise with the shift from tillagebasedagriculture to no-till, for instance. Andthe kinds of weeds and crop diseases can change.For example, the elevated moisture levels associatedwith no-till can promote soil-borne fungaldiseases that tillage previously kept in check.Indeed, the discovery of new crop diseases hassometimes accompanied the shift to no-till.Some of the changes that follow from no-tillcan take years or even decades to unfold, andfarmers need to remain vigilant and adaptableto new, sometimes unexpected, situations, suchas those that arise from shifts in soil and residueconditions or fertilizer management. Duringthis transition, there is a real risk of reducedyields and even failed crops. In the Palouse, forexample, some farmers who attempted no-tillin the 1980s are no longer in business. Consequently,farmers looking to switch to no-tillshould initially limit the converted acreage to10 to 15 percent of their total farm.Farmers who are new to no-till techniquesoften visit successful operations and form localor regional support groups, where they shareexperiences and discuss specific problems. Butthe advice they receive in areas with limited notilladoption can be incomplete or contradictory,www.SciAm.com © 2008 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, INC.SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN 75

![Graduate School Policies & Procedures Manual 2011 - 2012 [PDF]](https://img.yumpu.com/50747405/1/190x245/graduate-school-policies-procedures-manual-2011-2012-pdf.jpg?quality=85)