DOI: 10.1126/science.1111772 , 570 (2005); 309 Science et al ...

DOI: 10.1126/science.1111772 , 570 (2005); 309 Science et al ...

DOI: 10.1126/science.1111772 , 570 (2005); 309 Science et al ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

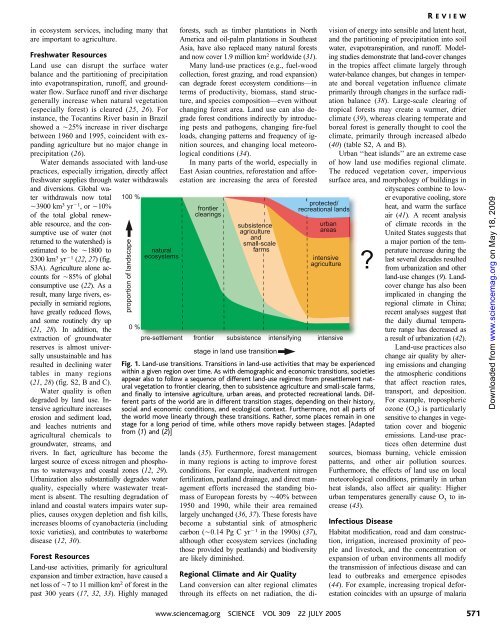

R EVIEWin ecosystem services, including many thatare important to agriculture.Freshwater ResourcesLand use can disrupt the surface waterb<strong>al</strong>ance and the partitioning of precipitationinto evapotranspiration, runoff, and groundwaterflow. Surface runoff and river dischargegener<strong>al</strong>ly increase when natur<strong>al</strong> veg<strong>et</strong>ation(especi<strong>al</strong>ly forest) is cleared (25, 26). Forinstance, the Tocantins River basin in Brazilshowed a È25% increase in river dischargeb<strong>et</strong>ween 1960 and 1995, coincident with expandingagriculture but no major change inprecipitation (26).Water demands associated with land-usepractices, especi<strong>al</strong>ly irrigation, directly affectfreshwater supplies through water withdraw<strong>al</strong>sand diversions. Glob<strong>al</strong> waterwithdraw<strong>al</strong>s now tot<strong>al</strong>È3900 km 3 yr j1 ,orÈ10%of the tot<strong>al</strong> glob<strong>al</strong> renewableresource, and the consumptiveuse of water (notr<strong>et</strong>urned to the watershed) isestimated to be È1800 to2300 km 3 yr j1 (22, 27)(fig.S3A). Agriculture <strong>al</strong>one accountsfor È85% of glob<strong>al</strong>consumptive use (22). As aresult, many large rivers, especi<strong>al</strong>lyin semiarid regions,have greatly reduced flows,and some routinely dry up(21, 28). In addition, theextraction of groundwaterreserves is <strong>al</strong>most univers<strong>al</strong>lyunsustainable and hasresulted in declining watertables in many regions(21, 28) (fig.S2,BandC).Water qu<strong>al</strong>ity is oftendegraded by land use. Intensiveagriculture increaseserosion and sediment load,and leaches nutrients andagricultur<strong>al</strong> chemic<strong>al</strong>s togroundwater, streams, and100 %proportion of landscape0 %natur<strong>al</strong>ecosystemsrivers. In fact, agriculture has become thelargest source of excess nitrogen and phosphorusto waterways and coast<strong>al</strong> zones (12, 29).Urbanization <strong>al</strong>so substanti<strong>al</strong>ly degrades waterqu<strong>al</strong>ity, especi<strong>al</strong>ly where wastewater treatmentis absent. The resulting degradation ofinland and coast<strong>al</strong> waters impairs water supplies,causes oxygen depl<strong>et</strong>ion and fish kills,increases blooms of cyanobacteria (includingtoxic vari<strong>et</strong>ies), and contributes to waterbornedisease (12, 30).Forest ResourcesLand-use activities, primarily for agricultur<strong>al</strong>expansion and timber extraction, have caused an<strong>et</strong> loss of È7to11millionkm 2 of forest in thepast 300 years (17, 32, 33). Highly managedforests, such as timber plantations in NorthAmerica and oil-p<strong>al</strong>m plantations in SoutheastAsia, have <strong>al</strong>so replaced many natur<strong>al</strong> forestsand now cover 1.9 million km 2 worldwide (31).Many land-use practices (e.g., fuel-woodcollection, forest grazing, and road expansion)can degrade forest ecosystem conditions—interms of productivity, biomass, stand structure,and species composition—even withoutchanging forest area. Land use can <strong>al</strong>so degradeforest conditions indirectly by introducingpests and pathogens, changing fire-fuelloads, changing patterns and frequency of ignitionsources, and changing loc<strong>al</strong> m<strong>et</strong>eorologic<strong>al</strong>conditions (34).In many parts of the world, especi<strong>al</strong>ly inEast Asian countries, reforestation and afforestationare increasing the area of forestedfrontierclearingssubsistenceagricultureandsm<strong>al</strong>l-sc<strong>al</strong>efarmspre-s<strong>et</strong>tlement frontier subsistence intensifying intensivestage in land use transitionlands (35). Furthermore, forest managementin many regions is acting to improve forestconditions. For example, inadvertent nitrogenfertilization, peatland drainage, and direct managementefforts increased the standing biomassof European forests by È40% b<strong>et</strong>ween1950 and 1990, while their area remainedlargely unchanged (36, 37). These forests havebecome a substanti<strong>al</strong> sink of atmosphericcarbon (È0.14 Pg C yr j1 in the 1990s) (37),<strong>al</strong>though other ecosystem services (includingthose provided by peatlands) and biodiversityare likely diminished.protected/recreation<strong>al</strong> landsintensiveagricultureurbanareas?Fig. 1. Land-use transitions. Transitions in land-use activities that may be experiencedwithin a given region over time. As with demographic and economic transitions, soci<strong>et</strong>iesappear <strong>al</strong>so to follow a sequence of different land-use regimes: from pres<strong>et</strong>tlement natur<strong>al</strong>veg<strong>et</strong>ation to frontier clearing, then to subsistence agriculture and sm<strong>al</strong>l-sc<strong>al</strong>e farms,and fin<strong>al</strong>ly to intensive agriculture, urban areas, and protected recreation<strong>al</strong> lands. Differentparts of the world are in different transition stages, depending on their history,soci<strong>al</strong> and economic conditions, and ecologic<strong>al</strong> context. Furthermore, not <strong>al</strong>l parts ofthe world move linearly through these transitions. Rather, some places remain in onestage for a long period of time, while others move rapidly b<strong>et</strong>ween stages. [Adaptedfrom (1) and (2)]Region<strong>al</strong> Climate and Air Qu<strong>al</strong>ityLand conversion can <strong>al</strong>ter region<strong>al</strong> climatesthrough its effects on n<strong>et</strong> radiation, the divisionof energy into sensible and latent heat,and the partitioning of precipitation into soilwater, evapotranspiration, and runoff. Modelingstudies demonstrate that land-cover changesin the tropics affect climate largely throughwater-b<strong>al</strong>ance changes, but changes in temperateand bore<strong>al</strong> veg<strong>et</strong>ation influence climateprimarily through changes in the surface radiationb<strong>al</strong>ance (38). Large-sc<strong>al</strong>e clearing oftropic<strong>al</strong> forests may create a warmer, drierclimate (39), whereas clearing temperate andbore<strong>al</strong> forest is gener<strong>al</strong>ly thought to cool theclimate, primarily through increased <strong>al</strong>bedo(40) (table S2, A and B).Urban ‘‘heat islands’’ are an extreme caseof how land use modifies region<strong>al</strong> climate.The reduced veg<strong>et</strong>ation cover, impervioussurface area, and morphology of buildings incityscapes combine to lowerevaporative cooling, storeheat, and warm the surfaceair (41). A recent an<strong>al</strong>ysisof climate records in theUnited States suggests thata major portion of the temperatureincrease during thelast sever<strong>al</strong> decades resultedfrom urbanization and otherland-use changes (9). Landcoverchange has <strong>al</strong>so beenimplicated in changing theregion<strong>al</strong> climate in China;recent an<strong>al</strong>yses suggest thatthe daily diurn<strong>al</strong> temperaturerange has decreased asa result of urbanization (42).Land-use practices <strong>al</strong>sochange air qu<strong>al</strong>ity by <strong>al</strong>teringemissions and changingthe atmospheric conditionsthat affect reaction rates,transport, and deposition.For example, troposphericozone (O 3)isparticularlysensitive to changes in veg<strong>et</strong>ationcover and biogenicemissions. Land-use practicesoften d<strong>et</strong>ermine dustsources, biomass burning, vehicle emissionpatterns, and other air pollution sources.Furthermore, the effects of land use on loc<strong>al</strong>m<strong>et</strong>eorologic<strong>al</strong> conditions, primarily in urbanheat islands, <strong>al</strong>so affect air qu<strong>al</strong>ity: Higherurban temperatures gener<strong>al</strong>ly cause O 3to increase(43).Infectious DiseaseHabitat modification, road and dam construction,irrigation, increased proximity of peopleand livestock, and the concentration orexpansion of urban environments <strong>al</strong>l modifythe transmission of infectious disease and canlead to outbreaks and emergence episodes(44). For example, increasing tropic<strong>al</strong> deforestationcoincides with an upsurge of m<strong>al</strong>ariaDownloaded from www.sciencemag.org on May 18, 2009www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL <strong>309</strong> 22 JULY <strong>2005</strong> 571