Senior English Critical Writing Handbook - Selwyn House School

Senior English Critical Writing Handbook - Selwyn House School

Senior English Critical Writing Handbook - Selwyn House School

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

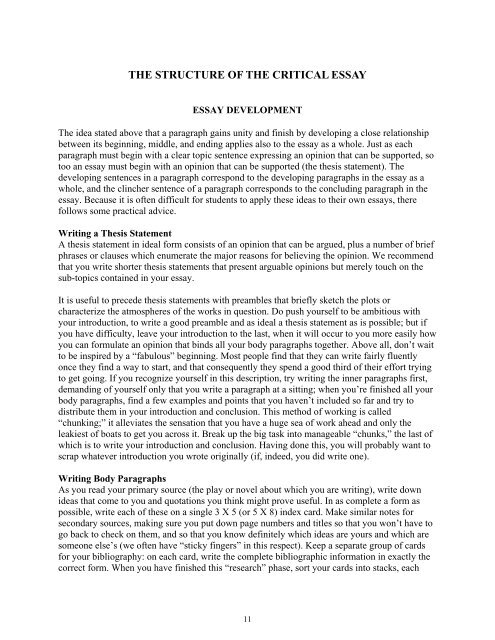

THE STRUCTURE OF THE CRITICAL ESSAYESSAY DEVELOPMENTThe idea stated above that a paragraph gains unity and finish by developing a close relationshipbetween its beginning, middle, and ending applies also to the essay as a whole. Just as eachparagraph must begin with a clear topic sentence expressing an opinion that can be supported, sotoo an essay must begin with an opinion that can be supported (the thesis statement). Thedeveloping sentences in a paragraph correspond to the developing paragraphs in the essay as awhole, and the clincher sentence of a paragraph corresponds to the concluding paragraph in theessay. Because it is often difficult for students to apply these ideas to their own essays, therefollows some practical advice.<strong>Writing</strong> a Thesis StatementA thesis statement in ideal form consists of an opinion that can be argued, plus a number of briefphrases or clauses which enumerate the major reasons for believing the opinion. We recommendthat you write shorter thesis statements that present arguable opinions but merely touch on thesub-topics contained in your essay.It is useful to precede thesis statements with preambles that briefly sketch the plots orcharacterize the atmospheres of the works in question. Do push yourself to be ambitious withyour introduction, to write a good preamble and as ideal a thesis statement as is possible; but ifyou have difficulty, leave your introduction to the last, when it will occur to you more easily howyou can formulate an opinion that binds all your body paragraphs together. Above all, don’t waitto be inspired by a “fabulous” beginning. Most people find that they can write fairly fluentlyonce they find a way to start, and that consequently they spend a good third of their effort tryingto get going. If you recognize yourself in this description, try writing the inner paragraphs first,demanding of yourself only that you write a paragraph at a sitting; when you’re finished all yourbody paragraphs, find a few examples and points that you haven’t included so far and try todistribute them in your introduction and conclusion. This method of working is called“chunking;” it alleviates the sensation that you have a huge sea of work ahead and only theleakiest of boats to get you across it. Break up the big task into manageable “chunks,” the last ofwhich is to write your introduction and conclusion. Having done this, you will probably want toscrap whatever introduction you wrote originally (if, indeed, you did write one).<strong>Writing</strong> Body ParagraphsAs you read your primary source (the play or novel about which you are writing), write downideas that come to you and quotations you think might prove useful. In as complete a form aspossible, write each of these on a single 3 X 5 (or 5 X 8) index card. Make similar notes forsecondary sources, making sure you put down page numbers and titles so that you won’t have togo back to check on them, and so that you know definitely which ideas are yours and which aresomeone else’s (we often have “sticky fingers” in this respect). Keep a separate group of cardsfor your bibliography: on each card, write the complete bibliographic information in exactly thecorrect form. When you have finished this “research” phase, sort your cards into stacks, each11