Marigolds 2011-1 - Prior Lake-Savage Area Schools

Marigolds 2011-1 - Prior Lake-Savage Area Schools

Marigolds 2011-1 - Prior Lake-Savage Area Schools

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

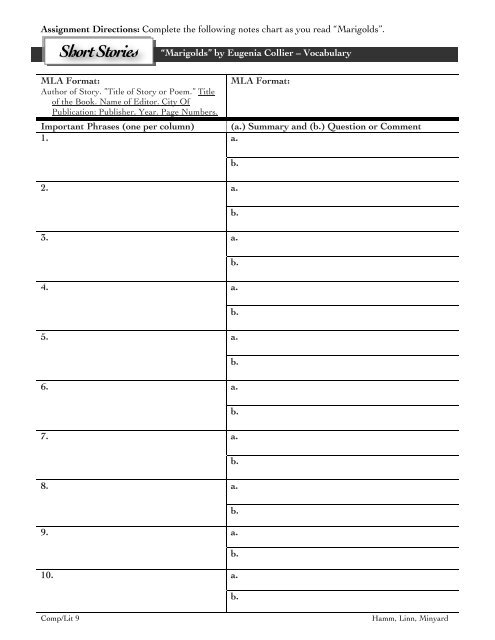

Assignment Directions: Complete the following notes chart as you read “<strong>Marigolds</strong>”.Short Stories“<strong>Marigolds</strong>” by Eugenia Collier – VocabularyMLA Format:Author of Story. ”Title of Story or Poem.” Titleof the Book. Name of Editor. City OfPublication: Publisher, Year. Page Numbers.Important Phrases (one per column)1.MLA Format:(a.) Summary and (b.) Question or Commenta.b.2.a.b.3.a.b.4.a.b.5.a.b.6.a.b.7.a.b.8.a.b.9.a.b.10.a.b.Comp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard

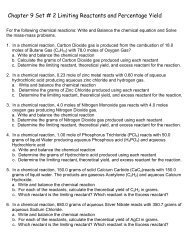

Literary Element: (Definition & Example)1.Simile: a direct comparison of twoessentially unlike things, often using like oras.Literary Elements: (Examples from the Text)1. Simile:Example: He hurried home like a snakeslithering into its hole.2.Metaphor: a less direct comparison of twoessentially unlike things.2. Metaphor:Example: The lamp of grandfather’s loveilluminated the difficult times after Sally’sdeath.3.Allusion: a reference to something inhistory or literature.3. Allusion:Example: All through high school, heplayed Romeo to my Juliet.4.Symbolism: something that is both itself,but also stands for or represents somethingother than itself.4. Symbolism:Example: When we give our mothersflowers on Mother’s Day, the flowers arereal flowers, but they also symbolize love,gratitude, loyalty, and other values.Plot Summary:Character Description:Miss Lottie:Theme:Comp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard

Short Stories“<strong>Marigolds</strong>” by Eugenia Collier – Journal PromptWhy Did I Do That?Think of a time when you did something in a fit of anger or frustration that you regretted later. Did youperhaps destroy something or hurt someone, simply because you were mad, depressed or having a hard time?Please write no less than a page on this topic, if you are having difficultly recalling a time, you may write fromthe other perspective, perhaps you were the recipient of someone’s rage, depression, frustration, etc. Explain indetail leaving little to my imagination.________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________Comp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard

<strong>Marigolds</strong>By Eugenia W. CollierWhen I think of the hometown of my youth, allthat I seem to remember is dust—the brown, crumblydust of late summer—arid, sterile dust that gets intothe eyes and makes them water, gets into the throatand between the toes of bare brown feet. I don’t knowwhy I should remember only the dust. Surely theremust have been lush green lawns and paved streetsunder leafy shade trees somewhere in town; butmemory is an abstract painting—it does not presentthings as they are, but rather as they feel. And so,when I think of that time and that place, I rememberonly the dry September of the dirt roads and grasslessyards of the shantytown where I lived. And one otherthing I remember, another incongruency ofmemory—a brilliant splash of sunny yellow against thedust—Miss Lottie’s marigolds.Whenever the memory of those marigoldsflashes across my mind, a strange nostalgia comeswith it and remains long after the picture has faded. Ifeel again the chaotic emotions of adolescence,illusive as smoke, yet as real as the potted geraniumbefore me now. Joy and rage and wild animalgladness and shame become tangled together in themulticolored skein of fourteen-going-on-fifteen as Irecall that devastating moment when I was suddenlymore woman than child, years ago in Miss Lottie’syard. I think of those marigolds at the strangest times; Iremember them vividly now as I desperately passaway the time.I suppose that futile waiting was the sorrowfulbackground music of our impoverished littlecommunity when I was young. The Depression thatgripped the nation was no new thing to us, for theblack workers of rural Maryland had always beendepressed. I don’t know what it was that we werewaiting for; certainly not for the prosperity that was“just around the corner,” for those were white folks’words, which we never believed. Nor did we wait forhard work and thrift to pay off in shining success, asthe American Dream promised, for we knew betterthan that, too. Perhaps we waited for a miracle,amorphous in concept but necessary if one were tohave the grit to rise before dawn each day and labor inthe white man’s vineyard until after dark, or to wanderabout in the September dust offering one’s sweat inreturn for some meager share of bread. But God waschary with miracles in those days, and so wewaited—and waited.We children, of course, were only vaguelyaware of the extent of our poverty. Having no radios,few newspapers, and no magazines, we wereComp/Lit 9-1-somewhat unaware of the world outside ourcommunity. Nowadays we would be called culturallydeprived and people would write books and holdconferences about us. In those days everybody weknew was just as hungry and ill clad as we were.Poverty was the cage in which we all were trapped,and our hatred of it was still the vague, undirectedrestlessness of the zoo-bred flamingo who knows thatnature created him to fly free.incongruency: inconsistency; lack of agreement orharmonymulticolored skein: The writer is comparing her manyfeelings to a skein, or long coiled piece of manycolored yarn.amorphous: vague, shapeless.chary: not generous.As I think of those days I feel most poignantlythe tag end of summer, the bright, dry times when webegan to have a sense of shortening days and theimminence of the cold.By the time I was fourteen, my brother Joeyand I were the only children left at our house, the olderones having left home for early marriage or the lure ofthe city, and the two babies having been sent torelatives who might care for them better than we. Joeywas three years younger than I, and a boy, andtherefore vastly inferior. Each morning our mother andfather trudged wearily down the dirt road and aroundthe bend, she to her domestic job, he to his dailyunsuccessful quest for work. After our few choresaround the tumbledown shanty, Joey and I were freeto run wild in the sun with other children similarlysituated.For the most part, those days are ill-defined inmy memory, running together and combining like afresh watercolor painting left out in the rain. Iremember squatting in the road drawing a picture inthe dust, a picture which Joey gleefully erased withone sweep of his dirty foot. I remember fishing forminnows in a muddy creek and watching sadly as theyeluded my cupped hands, while Joey laugheduproariously. And I remember, that year, a strangerestlessness of body and of spirit, a feeling thatsomething old and familiar was ending, and somethingunknown and therefore terrifying was beginning.Hamm, Linn, Minyard

One day returns to me with special clarity forsome reason, perhaps because it was the beginning ofthe experience that in some inexplicable way markedthe end of innocence. I was loafing under the greatoak tree in our yard, deep in some reverie which Ihave now forgotten, except that it involved somesecret, secret thoughts of one of the Harris boysacross the yard. Joey and a bunch of kids were borednow with the old tire suspended from an oak limb,which had kept them entertained for a while.“Hey, Lizabeth,” Joey yelled. He never talkedwhen he could yell. “Hey, Lizabeth, let’s gosomewhere.”I came reluctantly from my private world.“Where you want to go? What you want to do?”The truth was that we were becoming tired ofthe formlessness of our summer days. The idlenesswhose prospect had seemed so beautiful during thebusy days of spring now had degenerated to an almostdesperate effort to fill up the empty midday hours.“Let’s go see can we find some locusts on thehill,” someone suggested.Joey was scornful. “Ain’t no more locusts there.Y’all got ‘em all while they was still green.”The argument that followed was brief and notreally worth the effort. Hunting locust trees wasn’t funanymore by now.“Tell you what,” said Joey finally, his eyessparkling. “Let’s us go over to Miss Lottie’s.”Clarity: n.: clearness.Inexplicable: not explainable or understandable.The idea caught on at once, for annoying MissLottie was always fun. I was still child enough toscamper along with the group over rickety fences andthrough bushes that tore our already raggedy clothes,back to where Miss Lottie lived. I think now that wemust have made a tragicomic spectacle, five or sixkids of different ages, each of us clad in only onegarment—the girls in faded dresses that were too longor too short, the boys in patchy pants, their sweatybrown chests gleaming in the hot sun. A little cloud ofdust followed our thin legs and bare feet as wetramped over the barren land.When Miss Lottie’s house came into view westopped, ostensibly to plan our strategy, but actuallyto reinforce our courage. Miss Lottie’s house was themost ramshackle of all our ramshackle homes. Thesun and rain had long since faded its rickety frameComp/Lit 9-2-siding from white to a sullen gray. The boardsthemselves seemed to remain upright not from beingnailed together but rather from leaning together, like ahouse that a child might have constructed from cards.A brisk wind might have blown it down, and the factthat it was still standing implied a kind of enchantmentthat was stronger than the elements. There it stoodand as far as I know is standing yet—a gray, rottingthing with no porch, no shutters, no steps, set on acramped lot with no grass, not even any weeds—amonument to decay.In front of the house in a squeaky rocking chairsat Miss Lottie’s son, John Burke, completing theimpression of decay. John Burke was what was knownas queer-headed. Black and ageless, he sat rockingday in and day out in a mindless stupor, lulled by themonotonous squeak-squawk of the chair. A batteredhat atop his shaggy head shaded him from the sun.Usually John Burke was totally unaware of everythingoutside his quiet dream world. But if you disturbed him,if you intruded upon his fantasies, he would becomeenraged, strike out at you, and curse at you in somestrange enchanted language which only he couldunderstand. We children made a game of thinking ofways to disturb John Burke and then to elude hisviolent retribution.But our real fun and our real fear lay in MissLottie herself. Miss Lottie seemed to be at least ahundred years old. Her big frame still held traces of thetall, powerful woman she must have been in youth,although it was now bent and drawn. Her smooth skinwas a dark reddish brown, and her face had Indian-likefeatures and the stern stoicism that one associateswith Indian faces. Miss Lottie didn’t like intruderseither, especially children. She never left her yard, andnobody ever visited her. We never knew how shemanaged those necessities which depend on humaninteraction—how she ate, for example, or evenwhether she ate. When we were tiny children, wethought Miss Lottie was a witch and we made up talesthat we half believed ourselves about her exploits. Wewere far too sophisticated now, of course, to believethe witch nonsense. But old fears have a way ofclinging like cobwebs, and so when we sighted thetumbledown shack, we had to stop to reinforce ournerves.“Look, there she is,” I whispered, forgetting thatMiss Lottie could not possibly have heard me from thatdistance. “She’s fooling with them crazy flowers.”“Yeh, look at ‘er.”ostensibly: seemingly; apparently.retribution: n.: revenge.stoicism: calm indifference to pleasure or pain.Hamm, Linn, Minyard

Miss Lottie’s marigolds were perhaps thestrangest part of the picture. Certainly they did not fit inwith the crumbling decay of the rest of her yard.Beyond the dusty brown yard, in front of the sorry grayhouse, rose suddenly and shockingly a dazzling stripof bright blossoms, clumped together in enormousmounds, warm and passionate and sun-golden. Theold black witch-woman worked on them all summer,every summer, down on her creaky knees, weedingand cultivating and arranging, while the housecrumbled and John Burke rocked. For some perversereason, we children hated those marigolds. Theyinterfered with the perfect ugliness of the place; theywere too beautiful; they said too much that we couldnot understand; they did not make sense. There wassomething in the vigor with which the old womandestroyed the weeds that intimidated us. It shouldhave been a comical sight—the old woman with theman’s hat on her cropped white head, leaning over thebright mounds, her big backside in the air—but itwasn’t comical, it was something we could not name.We had to annoy her by whizzing a pebble into herflowers or by yelling a dirty word, then dancing awayfrom her rage, reveling in our youth and mocking herage. Actually, I think it was the flowers we wanted todestroy, but nobody had the nerve to try it, not evenJoey, who was usually fool enough to try anything.“Y’all git some stones,” commanded Joey nowand was met with instant giggling obedience aseveryone except me began to gather pebbles from thedusty ground. “Come on, Lizabeth.”I just stood there peering through the bushes,torn between wanting to join the fun and feeling that itwas all a bit silly.Comp/Lit 9“You scared, Lizabeth?”I cursed and spat on the ground—my favorite gestureof phony bravado. “Y’all children get the stones, I’llshow you how to use ‘em.”I said before that we children were notconsciously aware of how thick were the bars of ourcage. I wonder now, though, whether we were notmore aware of it than I thought. Perhaps we had somedim notion of what we were, and how little chance wehad of being anything else. Otherwise, why would wehave been so preoccupied with destruction? Anyway,the pebbles were collected quickly, and everybodylooked at me to begin the fun.“Come on, y’all.”We crept to the edge of the bushes thatbordered the narrow road in front of Miss Lottie’splace. She was working placidly, kneeling over theflowers, her dark hand plunged into the golden mound.-3-Suddenly zing—an expertly aimed stone cut the headoff one of the blossoms.“Who out there?” Miss Lottie’s backside camedown and her head came up as her sharp eyessearched the bushes. “You better git!”We had crouched down out of sight in thebushes, where we stifled the giggles that insisted oncoming. Miss Lottie gazed warily across the road for amoment, then cautiously returned to her weeding.Zing—Joey sent a pebble into the blooms, andanother marigold was beheaded.intimidated: v.: frightened.Miss Lottie was enraged now. She beganstruggling to her feet, leaning on a rickety cane andshouting. “Y’all git! Go on home!” Then the rest of thekids let loose with their pebbles, storming the flowersand laughing wildly and senselessly at Miss Lottie’simpotent rage. She shook her stick at us and startedshakily toward the road crying, “Git ‘long! John Burke!John Burke, come help!”Then I lost my head entirely, mad with thepower of inciting such rage, and ran out of the bushesin the storm of pebbles, straight toward Miss Lottie,chanting madly, “Old witch, fell in a ditch, picked up apenny and thought she was rich!” The childrenscreamed with delight, dropped their pebbles, andjoined the crazy dance, swarming around Miss Lottielike bees and chanting, “Old lady witch!” while shescreamed curses at us. The madness lasted only amoment, for John Burke, startled at last, lurched out ofhis chair, and we dashed for the bushes just as MissLottie’s cane went whizzing at my head.I did not join the merriment when the kidsgathered again under the oak in our bare yard.Suddenly I was ashamed, and I did not like beingashamed. The child in me sulked and said it was all infun, but the woman in me flinched at the thought of themalicious attack that I had led. The mood lasted allafternoon. When we ate the beans and rice that wassupper that night, I did not notice my father’s silence,for he was always silent these days, nor did I noticemy mother’s absence, for she always worked until wellinto evening. Joey and I had a particularly bitterargument after supper; his exuberance got on mynerves. Finally I stretched out upon the pallet in theroom we shared and fell into a fitful doze.When I awoke, somewhere in the middle of thenight, my mother had returned, and I vaguely listenedto the conversation that was audible through the thinwalls that separated our rooms. At first I heard nowords, only voices. My mother’s voice was like a cool,dark room in summer—peaceful, soothing, quiet. IHamm, Linn, Minyard

loved to listen to it; it made things seem all rightsomehow. But my father’s voice cut through hers,shattering the peace.“Twenty-two years, Maybelle, twenty-twoyears,” he was saying, “and I got nothing for you,nothing, nothing.”“It’s all right, honey, you’ll get something.Everybody out of work now, you know that.”“It ain’t right. Ain’t no man ought to eat hiswoman’s food year in and year out, and see hischildren running wild. Ain’t nothing right about that.”“Honey, you took good care of us when youhad it. Ain’t nobody got nothing nowadays.”“I ain’t talking about nobody else, I m talkingabout me. God knows I try.” My mother said somethingI could not hear, and my father cried out louder, “Whatmust a man do, tell me that?”“Look, we ain’t starving. I git paid every week,and Mrs. Ellis is real nice about giving me things. Shegonna let me have Mr. Ellis’s old coat for you thiswinter—”impotent: adj.: powerless; helpless.pallet: small bed or cot.“Damn Mr. Ellis’s coat! And damn his money!You think I want white folks’ leavings?“Damn, Maybelle”—and suddenly he sobbed,loudly and painfully, and cried helplessly andhopelessly in the dark night. I had never heard a mancry before. I did not know men ever cried. I coveredmy ears with my hands but could not cut off the soundof my father’s harsh, painful, despairing sobs. Myfather was a strong man who could whisk a child uponhis shoulders and go singing through the house. Myfather whittled toys for us, and laughed so loud that thegreat oak seemed to laugh with him, and taught ushow to fish and hunt rabbits. How could it be that myfather was crying? But the sobs went on, unstifled,finally quieting until I could hear my mother’s voice,deep and rich, humming softly as she used to hum to afrightened child.The world had lost its boundary lines. Mymother, who was small and soft, was now the strengthof the family; my father, who was the rock on which thefamily had been built, was sobbing like the tiniest child.Everything was suddenly out of tune, like a brokenaccordion. Where did I fit into this crazy picture? I donot now remember my thoughts, only a feeling of greatbewilderment and fear.Comp/Lit 9-4-Long after the sobbing and humming hadstopped, I lay on the pallet, still as stone with myhands over my ears, wishing that I too could cry andbe comforted. The night was silent now except for thesound of the crickets and of Joey’s soft breathing. Butthe room was too crowded with fear to allow me tosleep, and finally, feeling the terrible aloneness of 4A.M., I decided to awaken Joey.“Ouch! What’s the matter with you? What youwant?” he demanded disagreeably when I had pinchedand slapped him awake.“Come on, wake up.”“What for? Go ‘way.”I was lost for a reasonable reply. I could notsay, “I’m scared and I don’t want to be alone,” so Imerely said, “I’m going out. If you want to come, comeon.”The promise of adventure awoke him. “Goingout now? Where to, Lizabeth? What you going to do?”I was pulling my dress over my head. Until nowI had not thought of going out. “Just come on,” I repliedtersely.I was out the window and halfway down theroad before Joey caught up with me.“Wait, Lizabeth, where you going?”I was running as if the Furies were after me,as perhaps they were—running silently and furiouslyuntil I came to where I had half known I was headed:to Miss Lottie’s yard.The half-dawn light was more eerie thancomplete darkness, and in it the old house was like theruin that my world had become—foul and crumbling, agrotesque caricature. It looked haunted, but I was notafraid, because I was haunted too.“Lizabeth, you lost your mind?” panted Joey.Furies: in Greek and Roman mythology, spirits whopursue people who have committed crimes,sometimes driving them mad.I had indeed lost my mind, for all thesmoldering emotions of that summer swelled in meand burst—the great need for my mother who wasnever there, the hopelessness of our poverty anddegradation, the bewilderment of being neither childnor woman and yet both at once, the fear unleashedby my father’s tears. And these feelings combined inone great impulse toward destruction.Hamm, Linn, Minyard

“Lizabeth!”I leaped furiously into the mounds of marigoldsand pulled madly, trampling and pulling and destroyingthe perfect yellow blooms. The fresh smell of earlymorning and of dew-soaked marigolds spurred me onas I went tearing and mangling and sobbing while Joeytugged my dress or my waist crying, “Lizabeth, stop,please stop!”And then I was sitting in the ruined little gardenamong the uprooted and ruined flowers, crying andcrying, and it was too late to undo what I had done.Joey was sitting beside me, silent and frightened, notknowing what to say. Then, “Lizabeth, look!’I opened my swollen eyes and saw in front ofme a pair of large, calloused feet; my gaze lifted to theswollen legs, the age-distorted body clad in a tightcotton nightdress, and then the shadowed Indian facesurrounded by stubby white hair. And there was norage in the face now, now that the garden wasdestroyed and there was nothing any longer to beprotected.“M-miss Lottie!” I scrambled to my feet and juststood there and stared at her, and that was themoment when childhood faded and womanhoodbegan. That violent, crazy act was the last act ofchildhood. For as I gazed at the immobile face with thesad, weary eyes, I gazed upon a kind of reality whichis hidden to childhood. The witch was no longer awitch but only a broken old woman who had dared tocreate beauty in the midst of ugliness and sterility. Shehad been born in squalor and lived in it all her life. Nowat the end of that life she had nothing except a fallingdownhut, a wrecked body, and John Burke, themindless son of her passion. Whatever verve therewas left in her, whatever was of love and beauty andjoy that had not been squeezed out by life, had beenthere in the marigolds she had so tenderly cared for.Of course I could not express the things that Iknew about Miss Lottie as I stood there awkward andashamed. The years have put words to the things Iknew in that moment, and as I look back upon it, Iknow that that moment marked the end of innocence.Innocence involves an unseeing acceptance of thingsat face value, an ignorance of the area below thesurface. In that humiliating moment I looked beyondmyself and into the depths of another person. This wasthe beginning of compassion, and one cannot haveboth compassion and innocence.The years have taken me worlds away fromthat time and that place, from the dust and squalor ofour lives, and from the bright thing that I destroyed in ablind, childish striking out at God knows what. MissLottie died long ago and many years have passedsince I last saw her hut, completely barren at last, fordespite my wild contrition she never plantedmarigolds again. Yet, there are times when the imageof those passionate yellow mounds returns with apainful poignancy. For one does not have to beignorant and poor to find that his life is as barren asthe dusty yards of our town. And I too have plantedmarigolds.Contrition: n.: deep feelings of guilt and repentance.COPYRIGHT © 2000-2004 MISTERSUAREZ.COMComp/Lit 9-5-Hamm, Linn, Minyard

Short StoriesEugenia Collier’s Clarity Through ComparisonRead each of the passages from Eugenia Collier’s “<strong>Marigolds</strong>.” Explain your understanding of the passage, andpoint out specific similes, metaphors, and allusions.1. “I feel the chaotic emotions of adolescence, illusive as smoke, yet as real as the potted geranium beforeme now.”• Literary Element:• Meaning:2. “Joy and rage and wild animal gladness and shame become tangled together in the multicolored skein ofa 14-going-on-15…”• Literary Element:• Meaning:3. “…if one were to have the grit rise before dawn each day and labor in the white man’s vineyard…offering one’s sweat in return for some meager share of the bread.”• Literary Element:• Meaning:4. “Poverty was the cage in which we all were trapped, and our hatred of it was still the vague, undirectedrestlessness of the zoo-bred flamingo who knows that nature has created him to fly free.”• Literary Element:• Meaning:5. “…those days are ill-defined in my memory, running together and combining like a fresh water-colorpainting left out in the rain.”• Literary Element:• Meaning:Comp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard

Short Stories“The Daffodil Principle”Comp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard

Comp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard

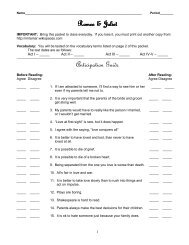

Short Stories“<strong>Marigolds</strong>” by Eugenia Collier – Journal Prompt“And I too have planted marigolds”<strong>Marigolds</strong> are the main symbol in Eugenia Collier’s story, and she emphasizes their symbolic value in theclosing line. Please read “The Daffodil Principle” and then answer the following journal prompt.Have you ever “planted marigolds” when life seemed especially disappointing? Have you seen someone elsecreate beauty to alter a grim landscape? Have you observed someone driven by anger or sadness to destroybeauty?Write your own “<strong>Marigolds</strong>” below.____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________Comp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard

Short Stories“<strong>Marigolds</strong>” by Eugenia Collier – Short Story RewriteDescription of Writing Assignment:In the short story “<strong>Marigolds</strong>” by Eugenia Collier, at one point in the story, the narrator, Lizabeth recalls anincident that occurred during the Great Depression when she was fourteen. After reading the historical fictionpiece, you are to rewrite a portion of the short story from Miss Lottie’s perspective.Circumstances of the Task/Directions:1. You must write a micro mini short story from Miss Lottie’s point of view.2. The assignment has to be at least 25 sentences and 250 words in length.3. You will work alone during the composition of the micro mini short story.4. You are allowed to use your texts and your notes during your rewrites.5. Your story must answer the following questions:a. How does Miss Lottie feel about her living conditions?b. How does she manage to take care of her son John Burke?c. Why does she plant marigolds?d. Why doesn’t she get angry with Lizabeth after Lizabeth destroys her marigolds?Example of how to start:Back when I was a kid, I was known as the weird girl that no one would talk to. I was also known as the poorest girl inmy home town of Jackson, Mississippi. I didn’t care about how my house looked back then and I certainly don’t care about howit looks now. As long as I have a roof over my head, I’m fine. I made a promise to my momma that I would grow marigoldswhen I got older.Comp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard

Short StoriesWhat is Poverty? Jo Goodwin Parker(Speech)The following selection was published in America's Other Children: Public <strong>Schools</strong> Outside Suburbs,by George Henderson in 1971 by the University of Oklahoma Press. The author has requested thatno biographical information about her be distributed. The essay is a personal account, addresseddirectly to the reader, about living in poverty.You ask me what is poverty? Listen to me. Here I am, dirty, smelly, and with no "proper"underwear on and with the stench of my rotting teeth near you. I will tell you. Listen to me.Listen without pity. I cannot use your pity. Listen with understanding. Put yourself in mydirty, worn out, ill-fitting shoes, and hear me.Poverty is getting up every morning from a dirt- and illness-stained mattress. The sheets havelong since been used for diapers. Poverty is living in a smell that never leaves. This is a smell ofurine, sour milk, and spoiling food sometimes joined with the strong smell of long-cookedonions. Onions are cheap. If you have smelled this smell, you did not know how it came. It isthe smell of the outdoor privy. It is the smell of young children who cannot walk the long darkway in the night. It is the smell of the mattresses where years of "accidents" have happened. Itis the smell of the milk which has gone sour because the refrigerator long has not worked, andit costs money to get it fixed. It is the smell of rotting garbage. I could bury it, but where is theshovel? Shovels cost money.Poverty is being tired. I have always been tired. They told me at the hospital when the lastbaby came that I had chronic anemia caused from poor diet, a bad case of worms, and that Ineeded a corrective operation. I listened politely - the poor are always polite. The poor alwayslisten. They don't say that there is no money for iron pills, or better food, or worm medicine.The idea of an operation is frightening and costs so much that, if I had dared, I would havelaughed. Who takes care of my children? Recovery from an operation takes a long time. I havethree children. When I left them with "Granny" the last time I had a job, I came home to findthe baby covered with fly specks, and a diaper that had not been changed since I left. Whenthe dried diaper came off, bits of my baby's flesh came with it. My other child was playing witha sharp bit of broken glass, and my oldest was playing alone at the edge of a lake. I madetwenty-two dollars a week, and a good nursery school costs twenty dollars a week for threechildren. I quit my job.Poverty is dirt. You can say in your clean clothes coming from your clean house, "Anybody canbe clean." Let me explain about housekeeping with no money. For breakfast I give my childrengrits with no oleo or cornbread without eggs and oleo. This does not use up many dishes. Whatdishes there are, I wash in cold water and with no soap. Even the cheapest soap has to besaved for the baby's diapers. Look at my hands, so cracked and red. Once I saved for twomonths to buy a jar of Vaseline for my hands and the baby's diaper rash. When I had savedenough, I went to buy it and the price had gone up two cents. The baby and I suffered on. Ihave to decide every day if I can bear to put my cracked sore hands into the cold water andstrong soap. But you ask, why not hot water? Fuel costs money. If you have a wood fire itcosts money. If you burn electricity, it costs money. Hot water is a luxury. I do not haveluxuries. I know you will be surprised when I tell you how young I am. I look so much older.My back has been bent over the wash tubs every day for so long, I cannot remember when IComp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard

ever did anything else. Every night I wash every stitch my school age child has on and justhope her clothes will be dry by morning.Poverty is staying up all night on' cold nights to watch the fire knowing one spark on thenewspaper covering the walls means your sleeping child dies in flames. In summer poverty iswatching gnats and flies devour your baby's tears when he cries. The screens are torn and youpay so little rent you know they will never be fixed. Poverty means insects in your food, inyour nose, in your eyes, and crawling over you when you sleep. Poverty is hoping it neverrains because diapers won't dry when it rains and soon you are using newspapers. Poverty isseeing your children forever with runny noses. Paper handkerchiefs cost money and all yourrags you need for other things. Even more costly are antihistamines. Poverty is cookingwithout food and cleaning without soap.Poverty is asking for help. Have you ever had to ask for help, knowing 6 your children willsuffer unless you get it? Think about asking for a loan from a relative, if this is the only wayyou can imagine asking for help. I will tell you how it feels. You find out where the office isthat you are supposed to visit. You circle that block four or five times. Thinking of yourchildren, you go in. Everyone is very busy. Finally, someone comes out and you tell her thatyou need help. That never is the person you need to see. You go see another person, and afterspilling the whole shame of your poverty all over the desk between you, you find that this isn'tthe right office after all-you must repeat the whole process, and it never is any easier at thenext place.You have asked for help, and after all it has a cost. You are again told to wait. You are toldwhy, but you don't really hear because of the red cloud of shame and the rising cloud ofdespair.Poverty is remembering. It is remembering quitting school in junior high because "nice"children had been so cruel about my clothes and my smell. The attendance officer came. Mymother told him I was pregnant. I wasn't, but she thought that I could get a job and help out. Ihad jobs off and on, but never long enough to learn anything. Mostly I remember beingmarried. I was so young then. I am still young. For a time, we had all the things you have.There was a little house in another town, with hot water and everything. Then my husband losthis job. There was unemployment insurance for a while and what few jobs I could get. Soon,all our nice things were repossessed and we moved back here. I was pregnant then. This housedidn't look so bad when we first moved in. Every week it gets worse. Nothing is ever fixed. Wenow had no money. There were a few odd jobs for my husband, but everything went for foodthen, as it does now. I don't know how we lived through three years and three babies, but wedid. I'll tell you something, after the last baby I destroyed my marriage. It had been a good one,but could you keep on bringing children in this dirt? Did you ever think how much it costs forany kind of birth control? I knew my husband was leaving the day he left, but there were nogoodbye between us. I hope he has been able to climb out of this mess somewhere. He nevercould hope with us to drag him down.That's when I asked for help. When I got it, you know how much it was? It was, and is,seventy-eight dollars a month for the four of us; that is all I ever can get. Now you know whythere is no soap, no needles and thread, no hot water, no aspirin, no worm medicine, no handcream, no shampoo. None of these things forever and ever and ever. So that you can seeComp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard

clearly, I pay twenty dollars a month rent, and most of the rest goes for food. For grits andcornmeal, and rice and milk and beans. I try my best to use only the minimum electricity. If Iuse more, there is that much less for food.Poverty is looking into a black future. Your children won't play with my boys. They will turnto other boys who steal to get what they want. I can already see them behind the bars of theirprison instead of behind the bars of my poverty. Or they will turn to the freedom of alcohol ordrugs, and find themselves enslaved. And my daughter? At best, there is for her a life likemine.But you say to me, there are schools. Yes, there are schools. My children have no extra books,no magazines, no extra pencils, or crayons, or paper and most important of all, they do nothave health. They have worms, they have infections, they have pink-eye all summer. They donot sleep well on the floor, or with me in my one bed. They do not suffer from hunger, myseventy-eight dollars keeps us alive, but they do suffer from malnutrition. Oh yes, I doremember what I was taught about health in school. It doesn't do much good.In some places there is a surplus commodities program. Not here. The country said it cost toomuch. There is a school lunch program. But I have two children who will already be damagedby the time they get to school.But, you say to me, there are health clinics. Yes, there are health clinics and they are in thetowns. I live out here eight miles from town. I can walk that far (even if it is sixteen miles bothways), but can my little children? My neighbor will take me when he goes; but he expects toget paid, one way or another. I bet you know my neighbor. He is that large man who spendshis time at the gas station, the barbershop, and the corner store complaining about thegovernment spending money on the immoral mothers of illegitimate children.Poverty is an acid that drips on pride until all pride is worn away. Poverty is a chisel that chipson honor until honor is worn away. Some of you say that you would do something in mysituation, and maybe you would, for the first week or the first month, but for year after yearafter year?Even the poor can dream. A dream of a time when there is money. Money for the right kindsof food, for worm medicine, for iron pills, for toothbrushes, for hand cream, for a hammer andnails and a bit of screening, for a shovel, for a bit of paint, for some sheeting, for needles andthread. Money to pay in money for a trip to town. And, oh, money for hot water and money forsoap. A dream of when asking for help does not eat away the last bit of pride. When the officeyou visit is as nice as the offices of other governmental agencies, when there are enoughworkers to help you quickly, when workers do not quit in defeat and despair. When you haveto tell your story to only one person, and that person can send you for other help and you don'thave to prove your poverty over and over and over again.I have come out of my despair to tell you this. Remember I did not come from another place oranother time. Others like me are all around you. Look at us with an angry heart, anger thatwill help me. Anger that will let you tell of me. The poor are always silent. Can you be silenttoo?Comp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard

Short StoriesWhat is Poverty? Jo Goodwin Parker(Speech)PREREADING – Journal Prompt: What is your definition of poverty?______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________What is Parker’s man idea?______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________What is her tone?______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________In what ways do you agree or disagree with Jo Goodwin Parker’s definition of poverty?______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________Comp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard

In what ways are Parker’s experiences of poverty similar to the way the characters in“<strong>Marigolds</strong>” experience poverty? Thoroughly explain citing the text for support.______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________In paragraph fourteen, Parker writes, “Even the poor can dream.” What does she dreamabout? How are her dreams different from your dreams?______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________What does Parker mean in the last paragraph when she asks, “Can you be silent too?”______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________What do you think was Parker’s purpose in writing this piece? What change or reactionis she looking for in the reader? Do you think this piece is successful in achieving thisreaction? Explain.______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________Comp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard

~Simile~Metaphor~Allusion~SymbolismName: ______________________By Eugenia CollierComp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard

Comp/Lit 9Hamm, Linn, Minyard