Thomas Raussen, Geoffrey Ebong and Jimmy Musiime - Foodnet

Thomas Raussen, Geoffrey Ebong and Jimmy Musiime - Foodnet

Thomas Raussen, Geoffrey Ebong and Jimmy Musiime - Foodnet

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Development in Practice, Volume 11, Number 4, August 2001<br />

Notice: This material may be prot~ct~d<br />

by copynght taw (Title 17 U.S. Code)<br />

<strong>Thomas</strong> <strong>Raussen</strong>, <strong>Geoffrey</strong> <strong>Ebong</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Jimmy</strong> <strong>Musiime</strong><br />

Scaling up agroforestry adoption requires technical innovations that are adapted to the<br />

environment. dem<strong>and</strong> driven. require low capital <strong>and</strong> labour inputs. <strong>and</strong> provide tangible<br />

benefits in a short time. The basic inputs. usually information <strong>and</strong> germplasm, need to be<br />

available. To reach out to millions of rural poor who require the products <strong>and</strong> services of<br />

agroforestry innovations, the scaling-up process has to be cost- <strong>and</strong> time efficient. The<br />

common project mode of scaling up is often too slow <strong>and</strong> expensive. <strong>and</strong> natural resource<br />

management issues need addressing on a large scale. Experiences from south-western<br />

Ug<strong>and</strong>a suggest that local governments <strong>and</strong> organisations can be encouraged to initiate<br />

cost-effective, large-scale adoption. The recent decentralisation process in Ug<strong>and</strong>a makes it<br />

feasible for farmer organisations to do this, while research <strong>and</strong> development organisations<br />

concentrate on their comparative advantages. which lie in developing innovations <strong>and</strong><br />

monitoring.<br />

Introduction<br />

As forest <strong>and</strong> plantation reserves decline, the dem<strong>and</strong> for tree products <strong>and</strong> services steadily<br />

increases in the densely populated south-western highl<strong>and</strong>s of Ug<strong>and</strong>a. Farmers are willing to<br />

grow trees on their farms but, as is typical in the highl<strong>and</strong>s of central Africa, on a small farm<br />

of less than I ha the farmer cannot set aside an area specifically for trees. Integrating trees into<br />

the farming system can provide important benefits to the farmer <strong>and</strong> the environment.<br />

Thro types of problem inhibit wider adoption of agroforestry:<br />

.Knowl"'g,md,k;I",boo"grofure"rym"O"'iolliM,"'kmg"M,""",d,,"d<br />

",dii""<br />

.Som'of'"'probkm'fu,w";,",grofure"ry;"p",;b"wru,;o"mlli'bo"md"d<br />

WOp'",;,elyby,"""mm~;,y","e,,"mby,",hoo,,hOld(G="y2000,Th;,;,<br />

P"";,"IMly '"e "" Im mm,gi"g w'"""ed rew""" ill 're" w;," "00,oc,"l;dMed<br />

["gm,""d fum, w"ic" ,re wmmoo ;" '"ill"we",m Ugmd,<br />

460 ISSN 0961-4524 printlISSN 1364-921.1 online 040460.11 @ 2001 Oxfam GB<br />

DOl; 10.1080109614520120066747 Caifa.1: Publishing

"ce<br />

:ratically<br />

lment<br />

at are adapted to the<br />

.<strong>and</strong> pro\'ide tangible<br />

~ennplasm, need to be<br />

.oducts <strong>and</strong> services of<br />

I/Id time efficient. The<br />

.<strong>and</strong> natural resource<br />

fS from south-western<br />

encouraged to initiate<br />

ss in Ug<strong>and</strong>a makes it<br />

!Iopment organisations<br />

'ping innovations <strong>and</strong><br />

s <strong>and</strong> services steadily<br />

Fanners are willing to<br />

\frica, on a small fann<br />

,. Integrating trees into<br />

he environment.<br />

as are tree seeds <strong>and</strong><br />

:ion must be h<strong>and</strong>led<br />

Jarrity 2000). This is<br />

,-ith non-consolidated,<br />

.~-11 @:I 2001 Ox/am GB<br />

~747 Carfax Publishing<br />

More effective natural resource management<br />

Successful <strong>and</strong> sustainable community-based approaches to managing watershed resources, of<br />

which agroforestry is an important component, share a number of requirements (Cooper <strong>and</strong><br />

Denning 2000; Garrity 2000):<br />

.Management approaches, as well as the proposed innovations, should be dem<strong>and</strong> driven-<br />

.A set of suitable innovations, such as agroforestry practices, <strong>and</strong> their key inputs, such as<br />

germplasm, needs to be available.<br />

.Efficient community organisations facilitate working together <strong>and</strong> resolving conflicts.<br />

.Scaling-up efforts need to be coordinated <strong>and</strong> facilitated.<br />

.A 'minimum external input strategy' needs to be put in place.<br />

While farmers <strong>and</strong> local organisations are quite capable of developing <strong>and</strong> fine-tuning<br />

innovations, they greatly benefit from being exposed to new approaches <strong>and</strong> technologies. All<br />

the other factors listed can be substantially promoted through efficient local governments, as<br />

shown in this case study from south-western Ug<strong>and</strong>a.<br />

In this paper, we describe h<strong>and</strong>s-on experience with community-led management of a<br />

watershed in Kabale District <strong>and</strong> we identify what we consider the important components of<br />

a successful strategy. We estimate that in Kabale District alone, more than 120,000 kIn of<br />

contour hedgerows will be required for soil conservation. At an average rate of 3000 seedlings<br />

per kilometre of hedgerow, this means about 360 million seedlings. The scope of this task<br />

makes intervening in the traditional project mode too slow <strong>and</strong> expensive. We argue that<br />

farmers <strong>and</strong> local government councils have to lead jointly in this task if it is to be achieved<br />

cost effectively <strong>and</strong> in reasonable time. Democratic decentralisation of government functions<br />

appears to be a key policy factor that is enabling successful watershed management.<br />

The study area<br />

The study was conducted in the 970 ha Katagata watershed in Bubare <strong>and</strong> Hannurwa<br />

Subcounties of Kabale District, which lies approximately between latitudes I°S <strong>and</strong> 1°30'S,<br />

<strong>and</strong> longitudes 29°18'E <strong>and</strong> 30°9'E. The district is mountainous, with altitudes ranging from<br />

1220 to 2500m (Rwabwoogo 1997). The topography is rugged, characterised by broken<br />

mountains, scattered Rift Valley lakes, deeply incised river valleys, steep convex slopes of<br />

10-60°, <strong>and</strong> gentle slopes of 5-10° adjacent to reclaimed papyrus swamps.<br />

The watershed, like about 70 per cent of the district, is covered with ferralitic s<strong>and</strong>y clay<br />

loams (Harrop 1960). Clay loams developed from phyllites predominate on the slopes, while<br />

silty clay <strong>and</strong> peat developed from peaty clay alluvium occur in the valleys. More than 50 years<br />

ago fanners began developing the bench terraces along the contours of the hills that are now<br />

a common feature in Kabale District farming systems.<br />

Kabale District has a temperate climate with bimodal rainfall, averaging I 000-1500 mm<br />

annually. Mean maximum <strong>and</strong> minimum temperatures are 23°C <strong>and</strong> 10°C, respectively<br />

(Department of Meteorology 1997). Although the area is mountainous, the favourable climate<br />

<strong>and</strong> the originally fertile soils coupled with historical factors have led to high population<br />

densities of about 246 people perkm2 (Rwabwoogo 1997).<br />

Smallholder agriculture is based on annual crops of sorghum, bean, <strong>and</strong> potato. Goats,<br />

sheep, <strong>and</strong> cattle are common, with upcoming dairy production based on fertile pastures at the<br />

valley bottoms <strong>and</strong> zero-grazing units.<br />

The Katagata watershed is typical of the district. It covers 9..7 km2 (about 0.5 per cent of the<br />

district) <strong>and</strong> comprises eight villages (local council (LC 1)), two parishes (LC 2), <strong>and</strong> two<br />

subcounties (LC 3).<br />

Development in Practice, Volume 11, Number 4, August 2001 461

e the mid-1980s when<br />

'curity after more than<br />

:<strong>and</strong>a 1997), however,<br />

'gramme. Government<br />

nda but also at lower<br />

,lative power has been<br />

'lber 4, August 2001<br />

More effective natural resource management<br />

decentralised. For example, the subcounty collects from every adult male a graduated tax <strong>and</strong><br />

retains 65 per cent of it. The remaining 35 per cent is shared among the county councils (5 per<br />

cent), parishes (5 per cent), <strong>and</strong> village councils (25 per cent). Levies <strong>and</strong> fees as well as<br />

allocations of unconditional <strong>and</strong> conditional grants from central government further add to the<br />

budgets of subcounties <strong>and</strong> districts. This gives lower levels of administration, beginning with<br />

the subcounty, <strong>and</strong> a quite substantial budget, which may surpass US$lOO,OOO even for a rural<br />

subcounty. Equally important is that by retaining much of the local taxes <strong>and</strong> fees, the local<br />

administration becomes directly answerable to its constituency.<br />

The provisions for local government elections guarantee widespread representation at the<br />

various councils <strong>and</strong> include quotas by gender, in that at least one-third of the councillors must<br />

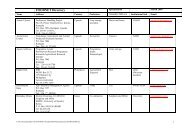

be women (see Figure 1).<br />

The Local Governments Act specifies functions <strong>and</strong> services that a district council can<br />

devolve to subcounty councils (LC 3) (Section 31 [4] Local Governments Act, Republic of<br />

U g<strong>and</strong>a, 1997). For managing natural resources, these include:<br />

.providing agricultural ancillary field services, such as extension;<br />

.controlling soil erosion <strong>and</strong> protecting local wetl<strong>and</strong>s;<br />

.taking measures to prohibit, restrict, prevent, regulate or abate destruction of grass, forest or<br />

bush by fIfe, including the requisition of able-bodied males to extinguish such fires <strong>and</strong> to<br />

cut fire-breaks <strong>and</strong> generally protect the local environment;<br />

.providing measures to prevent <strong>and</strong> contain food shortages, including relief work, the<br />

provision of seed, <strong>and</strong> the storage of foodstuffs.<br />

All of these functions <strong>and</strong> services are relevant to adopting agroforestry innovations in the<br />

community. While many councillors are aware of these provisions, they often ask for technical<br />

support in order to translate them into action. Others need to be made more aware of both the<br />

usefulness of a community-based approach as well as the legal backing <strong>and</strong> the obligations<br />

they have. A number of programmes are in place to improve the capability of local councils.<br />

All levels of local government have the specific task of advising higher levels of government<br />

<strong>and</strong> can thereby influence policy.<br />

An interesting example of such community action is emerging in Kabale District of southwestern<br />

Ug<strong>and</strong>a, where farmers in the Katagata river catchment of Bubare <strong>and</strong> Hamurwa<br />

Subcounties (LC 3) have moved forward to begin managing a critical watershed in which soil<br />

erosion <strong>and</strong> related sedimentation are serious problems (<strong>Raussen</strong> 2000).<br />

Dem<strong>and</strong>-driven approach<br />

A crucial prerequisite for successful community action appears to be a common underst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

that an important problem exists <strong>and</strong> that communities are willing to invest resources to tackle<br />

it. During the exceptionally heavy El Nifio rains of 1997-1998, farmers of Kyantobi village at<br />

the lower end of the Katagata river catchment experienced the typical problems of erosion<br />

from the fields on the steep slopes <strong>and</strong> flooding <strong>and</strong> sedimentation on their best valley-bottom<br />

soils. This erosion during heavy rainfall leads to massive loss of fertile topsoil on the slopes;<br />

destruction of crops, particularly at the valley bottoms; <strong>and</strong> deposits of infertile s<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> at<br />

times even large stones on the fertile valley-bottom soils. Although the causes of these<br />

problems usually lie in the upper parts of a watershed, the immediate impact is highest in the<br />

lower parts.<br />

For help to deal with the problems, representatives from the village at the lower end of the<br />

watershed contacted the Agroforestry Research <strong>and</strong> Development Project jointly implemented<br />

Development in Practice, Volume 11, Number 4, August 2001<br />

463

entre for Research in<br />

ne obvious to project<br />

~Iems of runoff would<br />

rly so since farmers'<br />

le would not have any<br />

~Ip with training <strong>and</strong><br />

mise the key element<br />

:)ndition. Community<br />

ops <strong>and</strong> planted trees<br />

ies can make suitable<br />

)y-Iaws. Furthermore,<br />

I organise discussions<br />

~Is to initiate contacts<br />

.means that a system<br />

se may be available<br />

~s can often provide<br />

1 of the innovations;<br />

t is common to leave<br />

; are not sufficiently<br />

their village council<br />

he project staff on a<br />

exposure led them<br />

ation for alleviating<br />

I water conservation<br />

ry fodder, stakes for<br />

~xperiment with <strong>and</strong><br />

This possibility of<br />

siasm high.<br />

!'ul means for giving<br />

'isit fanners already<br />

)articipants, making<br />

providing transport<br />

other agroforestry<br />

, also wanted to try<br />

robusta <strong>and</strong> AInus<br />

~oing much of the<br />

More effective natural resource management<br />

.Rotational woodlots on degraded l<strong>and</strong> for fuelwood <strong>and</strong> stake production while at the same<br />

time improving the soil (AFRENA-Ug<strong>and</strong>a 2000).<br />

.Fruit trees for home consumption of fruit, particularly the newly introduced deciduous trees<br />

(apple, pear, plum), which can produce in the highl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> generate cash in urban markets<br />

in lower-lying areas (AFRENA-Ug<strong>and</strong>a 2000).<br />

Community organisations<br />

Why are effective community organisations so important for disseminating agroforestry<br />

information <strong>and</strong> systems cost-effectively <strong>and</strong> successfully?<br />

Most dissemination about agroforestry is currently done in a project mode. Much effort is<br />

required to establish suitable structures for the process, which may include forming<br />

dissemination groups, attending to agroforestry-related disputes in the community, <strong>and</strong> posting<br />

extension officers in the target areas.<br />

Working through established community groups allows the development organisation to<br />

concentrate on what it is best at: providing training <strong>and</strong> the few necessary materials. It also<br />

allows the local council to concentrate on its strengths: planning, mobilising the community,<br />

facilitating joint efforts, <strong>and</strong> resolving conflicts. These functions are important, particularly if<br />

one considers how much time <strong>and</strong> funds development organisations, as outsiders, usually<br />

invest to provide these services. Democratically elected village or parish councillors are<br />

respected <strong>and</strong> well placed to fulfil these functions more cost-effectively.<br />

Local communities, as they plan, often benefit from the technical backup that development<br />

organisations can provide. In our case study, for example, villagers much appreciated the<br />

participatory mapping exercise, both for its team building <strong>and</strong> for its usefulness as a tool for<br />

planning natural resource management. Farmers met in the field <strong>and</strong> mapped a whole slope.<br />

To their own surprise, it was not always easy to identify the owners of fields ( over 40 on one<br />

slope). They then determined the measures required for soil conservation. Based on their map<br />

(see Figure 2), the dissemination staff found it simple to calculate the length of the contour<br />

hedges <strong>and</strong> the number of seedlings that each farmer would need (see Table I). This approach<br />

is an important improvement over the common practice in which projects determine a rather<br />

abstract target for nursery production (often based on donor rather than farmer dem<strong>and</strong>). In the<br />

case study, each farmer could now decide the number of seasons required to raise the seedlings<br />

<strong>and</strong> whether to do this individually or with a group of fellow farmers. We expect this approach<br />

to strongly motivate the farmers.<br />

Empowering farmer groups <strong>and</strong> their local councils to plan <strong>and</strong> implement the conservation<br />

exercises should enhance the scaling-up process. Already in the Katagata watershed, 164<br />

farmers have become involved in agroforestry arid have established 32 nurseries. As<br />

mentioned, several hundred million seedlings would be required to establish contour hedges all<br />

over Kabale District. This can be achieved in a reasonable time only if planning, raising<br />

seedlings, <strong>and</strong> establishing them in the field becomes a self -propelled <strong>and</strong> sustainable exercise.<br />

Local councils appear to have the authority <strong>and</strong> most of the resources to lead this process.<br />

Local government<br />

Importantly, local government in villages <strong>and</strong> parishes can instigate community action <strong>and</strong><br />

resolve conflicts; higher levels in the hierarchy have their strengths in coordinating, making<br />

contacts <strong>and</strong> requests, assisting in monitoring, <strong>and</strong> providing funds.<br />

In Ug<strong>and</strong>a, a typical district has between 15 <strong>and</strong> 20 subcounties, <strong>and</strong> the subcounty appears<br />

to be the suitable unit for undertaking these functions. It is the lowest level with budgetary<br />

power <strong>and</strong> corporate rights, as it keeps <strong>and</strong> spends 65 per cent of the graduated tax it collects.<br />

?er 4, August 2001 465<br />

Development in Practice, Volume 11, Number 4, August 2001

ivities as typesetting<br />

lart of it referred to<br />

imilar problems or<br />

Id information, such<br />

ful <strong>and</strong> sustainable.<br />

of labour <strong>and</strong> cash.<br />

>n approaches need<br />

I from development<br />

which will largely<br />

heap as possible in<br />

ide range of other<br />

ke schools, health,<br />

locally supported<br />

forestry extension<br />

er inputs than are<br />

m (ICRAF 2000)<br />

methods. If local<br />

)lute minimum of<br />

gennplasm. Most<br />

kes, <strong>and</strong> watering<br />

~se items <strong>and</strong> can<br />

j that quality fruit<br />

Juts <strong>and</strong> probably<br />

tions will depend<br />

:ar duties <strong>and</strong> not<br />

~refore important<br />

eir perception of<br />

o allocate their<br />

-e seeing just the<br />

to develop clear<br />

unity action <strong>and</strong><br />

Iver whether the<br />

dous. We could<br />

!1 watershed <strong>and</strong><br />

Ilarly important<br />

~m, may initiate<br />

'xperiments, we<br />

4, August 2001<br />

Conclusions<br />

More effective natural resource management<br />

Scaling up adoption of agroforestry innovations from individual farms to watersheds <strong>and</strong> whole<br />

farming systems is a formidable task. Despite the impressive impact made by various<br />

agroforestry development projects in south-western Ug<strong>and</strong>a, the task is far too large to be<br />

accomplished in a project mode. Only if communities-convinced by the success of early<br />

agroforestry adopters-take responsibility for searching for solutions, adapting <strong>and</strong> adopting<br />

them to their complex environmental problems, <strong>and</strong> implementing them on a large scale, will<br />

environmental degradation in the watershed be addressed in time <strong>and</strong> with affordable resources.<br />

This requires enabling the community to underst<strong>and</strong> the problems <strong>and</strong> plan interventions.<br />

Local farmer organisations <strong>and</strong> local governments are best able to mobilise the community<br />

<strong>and</strong> solve local problems, with research <strong>and</strong> development organisations providing technical<br />

backup <strong>and</strong> quality germplasm. This proposed mode is different from the traditional<br />

technology-transfer approach, in which researchers generate technologies <strong>and</strong> extension<br />

specialists extend them to farmers. Here we propose enabling farmers to analyse <strong>and</strong> plan a<br />

range of options <strong>and</strong> solutions. Most importantly, they should themselves identify these<br />

options <strong>and</strong> solutions <strong>and</strong> maintain an open <strong>and</strong> regular dialogue with all the institutions<br />

involved. Another key ingredient for a successful approach is patience: patience to allow<br />

initiatives to grow <strong>and</strong> farmers to plan <strong>and</strong> explore them for themselves.<br />

The scaling-up process this paper describes is still in its infancy <strong>and</strong> needs more social<br />

research <strong>and</strong> quantification. However, the achievements made with limited physical inputs<br />

from outside are remarkable.<br />

Ug<strong>and</strong>a is advanced in the decentralisation process; however, even in countries with weaker<br />

local governments, the potential to make use of local organisations in scaling up innovations<br />

often appears to be untapped. Greater efforts are needed to mobilise local government officials<br />

as promoters of natural resource management practices.<br />

References<br />

AFRENA-Ug<strong>and</strong>a (2000) Agroforestry Trends, Kampala: Agroforestry Research Network<br />

for Africa.<br />

Cooper, P. J. M. <strong>and</strong> G. L. Defining (eds.) (2000) Scaling Up the Impact of Agroforestry<br />

Research, Nairobi: International Centre for Research in Agroforestry.<br />

Cooper, P. J., R. R. B. Leakey, M. R. Rao <strong>and</strong> L. Reynolds (1996) , Agroforestry <strong>and</strong> the<br />

mitigation of l<strong>and</strong> degradation in the humid <strong>and</strong> sub-humid tropics of Africa', Experimental<br />

Agriculture 32:235-290.<br />

Department of Meteorology (1997) Monthly <strong>and</strong> Annual Weather Data for Kabale District,<br />

Kampala: Ug<strong>and</strong>a Ministry of Natural Resources.<br />

Garrity, D. (2000) 'The farmer-driven L<strong>and</strong>care movement: an institutional innovation with<br />

implications for extension <strong>and</strong> research', in Cooper <strong>and</strong> Denning (eds.) Scaling Up the Impact<br />

of Agroforestry Research.<br />

Harrop, J. F. (1960) The Soils of the Western Province of Ug<strong>and</strong>a, Memoirs of the Research<br />

Division, 1/6, Kampala: Ug<strong>and</strong>a Department of Agriculture.<br />

International Centre for Research in Agroforestry (ICRAF) (2000) Paths to Prosperity<br />

through Agroforestry: ICRAF's Corporate Strategy 2001-2010, Nairobi: International Centre<br />

for Research in Agroforestry.<br />

<strong>Raussen</strong>, T. (2000) 'Scaling up agroforestry adoption: what role for democratically elected<br />

<strong>and</strong> decentralized government structures in Ug<strong>and</strong>a?', in Cooper <strong>and</strong> Denning (eds.) Scaling<br />

Up the Impact of Agroforestry Research.<br />

Development in Practice, Volume 11, Number 4, August 2001<br />

469