Minerals Extraction and Archaeology: A Practice Guide - CBI

Minerals Extraction and Archaeology: A Practice Guide - CBI

Minerals Extraction and Archaeology: A Practice Guide - CBI

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

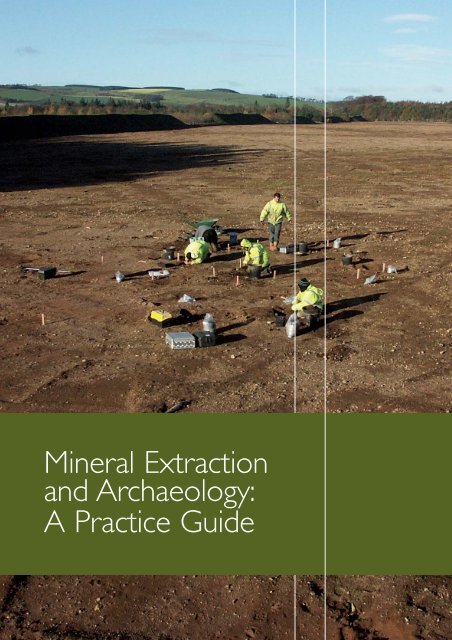

Mineral <strong>Extraction</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>Archaeology</strong>:A <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>

This document has been prepared by the <strong>Minerals</strong> <strong>and</strong> Historic Environment Forum as anaid to planning authorities, mineral planners, mineral operators, archaeologists <strong>and</strong> consultants.It provides guidance specifically for dealing with archaeological remains as part of mineraldevelopment through the planning process.The principal purpose of this <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> is toprovide clear <strong>and</strong> practical guidance on the archaeological evaluation of mineral development sites,particularly for the determination of individual planning applications for minerals development.It should ensure that adequate information is acquired in a cost-effective way so that an informedplanning decision can be made.The guide also provides some information on the mitigationtechniques that could be employed.Government planning policy relating to archaeology <strong>and</strong> mineral extraction is set out in MineralPolicy Statement 1 (DCLG 2006a) <strong>and</strong> Planning Policy Guidance Note 16 (DoE 1990). EnglishHeritage’s policy towards mineral extraction can be found in Mineral <strong>Extraction</strong> <strong>and</strong> the HistoricEnvironment (2008a).This <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> builds on the <strong>CBI</strong> Archaeological Investigations Codeof <strong>Practice</strong> (1991) with the aim of ensuring that planning decisions are informed by investigationsthat are proportionate to the archaeological potential of a site, <strong>and</strong> reasonable in all other respects.This <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> deals specifically with l<strong>and</strong>-based mineral extraction in Engl<strong>and</strong>. It is confined toarchaeological considerations <strong>and</strong> does not cover st<strong>and</strong>ing buildings for which other guidance exists.Good practice for mineral extraction <strong>and</strong> archaeology in the marine environment is dealt withelsewhere (BMAPA/EH 2003), as is a strategy for dealing with archaeology in relation to peatextraction (English Heritage 2002c).The guide was authored by Clive Waddington ofArchaeological Research Services Ltd on behalfof the <strong>Minerals</strong> <strong>and</strong> Historic Environment Forumthat includes:Association of Local Government ArchaeologicalOfficers: Engl<strong>and</strong>British Aggregates AssociationConfederation of British Industry <strong>Minerals</strong> GroupEnglish HeritageInstitute of Field ArchaeologistsMining Association of the UKPlanning Officers SocietyQuarry Products AssociationSt<strong>and</strong>ing Committee of Archaeological Unit ManagersThe <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> carries the endorsement of all theorganisations represented on the Forum <strong>and</strong> each iscommitted to promoting the practices it contains.The Forumcontinues to meet to discuss issues relating to archaeologicalpractice <strong>and</strong> mineral extraction <strong>and</strong> promote good practice.It can contacted by writing to the address below.The <strong>Minerals</strong> <strong>and</strong> Historic Environment Forumc/o The Executive Secretary<strong>CBI</strong> <strong>Minerals</strong> GroupCentre Point103 New Oxford StreetLondonWC1A 1DUThe writing <strong>and</strong> production of this guidance was supportedby the Aggregates Levy Sustainability Fund distributedby English Heritage on behalf of the Department forEnvironment, Food <strong>and</strong> Rural Affairs (Defra).Cover: Excavation in progress on a Bronze Age roundhouse at Lanton Quarry, Northumberl<strong>and</strong>. © Archaeological Research Services Ltd1

CONTENTSpageIntroduction 3Agreed basis for the guide 4The planning process 8Overview 8Local Development Frameworks 8Planning applications 10Screening 10Scoping 11Environmental impact assessment <strong>and</strong> 12pre-determination measuresDetermination 14Post-permission mitigation measures 14Techniques 17Aerial photography 17Archaeological survey 18Desk-based assessment 19Evaluation trenching 19Excavation 21Fieldwalking 22Geomorphological mapping 22Geophysical survey <strong>and</strong> remote sensing 23Palaeoenvironmental analysis 24Post-excavation, archive <strong>and</strong> dissemination 25Sediment analysis 26Strip, map <strong>and</strong> sample 27Test pits 28Watching brief 28References <strong>and</strong> key publications 29Sources of useful information<strong>and</strong> adviceBack page2

AGREED BASIS FOR THE GUIDE5 The Forum agrees that:• A steady, adequate <strong>and</strong> sustainable supply of mineralsis essential to the nation’s prosperity, infrastructure<strong>and</strong> quality of life.• <strong>Minerals</strong> are finite <strong>and</strong> irreplaceable resources thatcan only be worked where they occur. Proposals forthe extraction of those resources will only proceedif the minerals operator considers the commercialrisk acceptable.• Archaeological remains are a finite <strong>and</strong> irreplaceableresource that may occur anywhere. In many casesthey are highly fragile <strong>and</strong> vulnerable to damage<strong>and</strong> destruction.• Archaeological resources are not all equal in value;those of international or national importance requirethe highest level of protection from competingdevelopment. Equally, few archaeological resourcesare without value <strong>and</strong> this can sometimes only beestablished by investigation.• It is the role of the planning system to reconcile theneeds of the historic environment <strong>and</strong> mineralsdevelopment in the context of sustainabledevelopment.These points are explained more fully below.A steady, adequate <strong>and</strong> sustainable supply ofminerals is essential6 ‘<strong>Minerals</strong> are essential to the nation’s prosperity <strong>and</strong>quality of life, not least in helping to create <strong>and</strong> developsustainable communities. It is essential that there is anadequate <strong>and</strong> steady supply of material to providethe infrastructure, buildings <strong>and</strong> goods that society,industry <strong>and</strong> the economy needs but that this provisionis made in accordance with the principles of sustainabledevelopment’, <strong>Minerals</strong> Policy Statement 1, paragraph 1(MPS1, DCLG 2006a).<strong>Minerals</strong> are finite <strong>and</strong> irreplaceable resources7 Mineral extraction can only occur where viableminerals are found. In that respect it is different frommost other forms of development in that the scope forconsidering alternative locations is limited by geology.Thisis especially true in the case of less abundant mineralssuch as coal, industrial minerals, silica s<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> distinctivebuilding stone which themselves may be locally, regionallyor nationally important.What is often forgotten is thatalthough recyclable, primary minerals are finite <strong>and</strong>irreplaceable; in the context of sustainability, it is essentialto secure their prudent <strong>and</strong> efficient use <strong>and</strong> to preventneedless sterilisation of mineral resources.Archaeological remains are a finite <strong>and</strong>irreplaceable resource8 The removal of archaeological remains is an irreversibleprocess; once they have been removed they cannever be replaced. Humans have occupied Engl<strong>and</strong> fromas far back as 700,000 years ago, <strong>and</strong> continuously sincethe last Ice Age around 13,000 years ago. Evidence ofhuman activity can be recognised in different forms <strong>and</strong>at different scales, ranging from the very local to wholel<strong>and</strong>scapes. Between areas, however, there can be largevariations in the number <strong>and</strong> type of archaeologicalremains.There is also likely to be a relationship betweenthe origin <strong>and</strong> age of a l<strong>and</strong>form, the history of itssubsequent use by people, the likely characteristicsof any archaeological remains <strong>and</strong> the probability ofthem surviving.9 For example, remains are often abundant on s<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong>gravel terraces.This is because these areas are typicallyfree-draining <strong>and</strong> fertile, <strong>and</strong> were consequently favouredas locations for Neolithic monuments, later prehistoric<strong>and</strong> Roman settlements <strong>and</strong> field systems <strong>and</strong> Anglo-Saxon settlements. In hard-rock areas with little orno drift cover, the archaeological associations may bedifferent, typically comprising upst<strong>and</strong>ing stone cairns,st<strong>and</strong>ing stones, house platforms, field systems, prehistoricrock art, rock shelters, cave sites <strong>and</strong> artefact scatters.Another important relationship between a l<strong>and</strong>form<strong>and</strong> its archaeological potential is the occurrence ofPalaeolithic material – typically flint tools <strong>and</strong> faunalremains, such as mammoth bones – within s<strong>and</strong><strong>and</strong> gravel deposits themselves.The likelihood ofencountering such remains depends on both the ageof the l<strong>and</strong>form unit <strong>and</strong> the circumstances of itsdeposition. In some cases monitoring of archaeologicallysensitive deposits may form an important part ofa mitigation strategy, although the in situ preservationof such Palaeolithic remains will rarely be practicalor justified.4

454 Dix Quarry, Stanton Harcourt,Oxfordshire: archaeologistsexcavate remains of mammoths<strong>and</strong> stone tools dating back to apreviously unknown warm interglacialepisode 200,000 years ago.© Hanson Aggregates5 Excavation of a prehistoric pitalignment at Barrow upon Trent,Derbyshire. © Trent & Peak<strong>Archaeology</strong>application.Whenever possible, it should also alertprospective developers to any archaeological issues thatwill need to be addressed in respect of allocated sites.Areas of higher <strong>and</strong> lower archaeological potentialshould normally be defined within the LDF to ensurethat planning authorities give appropriate considerationto archaeology when identifying future working areas.The better the quality of the information available, thegreater the certainty with which those locations may beidentified <strong>and</strong> the lower the potential risks to all parties<strong>and</strong> to the archaeological resource. Planning authoritiesshould consult local authority archaeological curatorsto ensure they are provided with the information <strong>and</strong>advice needed to inform <strong>and</strong> underpin the LDF. Furtheradvice on the archaeological input to LDFs is includedin the relevant section below (paras 24–29).18 Early identification of the potential impacts of aproposed development is a key element in workingtowards the goal of achieving sustainable mineralsdevelopment <strong>and</strong> appropriate treatment ofarchaeological remains. Applicants are stronglyrecommended to engage in pre-application discussionsas a way of helping them to formulate their proposals.Applications that are not supported by adequateinformation can take longer to determine, becausefurther information will need to be provided.19 Sometimes the planning authority will decide that apre-determination archaeological evaluation is neededbefore an informed <strong>and</strong> reasonable decision can betaken on an application.This evaluation should drawon field techniques appropriate to the l<strong>and</strong>forms <strong>and</strong>types of archaeology expected. In addition, it shoulduse Historic L<strong>and</strong>scape Character data, available fromsome HERs, to contextualize the site more widely intothe l<strong>and</strong>scape.The brief for a pre-determinationprogramme of work should be developed by the localauthority archaeological curator in discussion withthe consultant or contractor acting on behalf of thedeveloper, in accordance with the detail in paragraphs32–37 of this <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>.The programme shouldbe consistent with best practice across the country,proportionate to the archaeological potential of the site<strong>and</strong> reasonable in all other respects. PPG 16, paragraph21, states that pre-determination evaluation is ‘normallya rapid <strong>and</strong> inexpensive operation’ (relative to theoverall scale of the operation) which helps to definethe character <strong>and</strong> extent of the archaeological remainsthat exist in the area of a proposed development.Theavailability of this information early in the process is animportant risk management tool that will give the6

developer <strong>and</strong> the curator a clearer indication of thearchaeological potential of the site <strong>and</strong> thereby minimisethe possibility of the unexpected. In most instances,evaluations are also the key to identifying the order ofcosts involved in dealing with any remains. If a site isto be developed in phases over a long period of timethere is merit in the developer producing a site strategyor masterplan, particularly if a number of differentarchaeological contractors become involved over thelife of the site.20 An archaeological assessment of the proposeddevelopment, including the findings of any initialinvestigations, should be incorporated within anyEnvironmental Impact Assessment (EIA, see paras32–5) accompanying the planning application. Furtherinformation on the EIA process <strong>and</strong> content can befound on the websites of Planarch <strong>and</strong> the EIA Centre.The developer should be prepared for the planningauthority to ask for additional investigation in the lightof information gathered by the initial work.This isentirely reasonable, provided that it is consistent withthe requirements set out in paragraph 19 above <strong>and</strong>PPG 16 paragraph 21.21 If planning permission is granted, this may be subjectto further archaeological work being undertaken or arequirement to preserve in situ remains identified duringpre-determination evaluation. Further details of measuresthat can be specified through planning conditions <strong>and</strong>other obligations are contained in the section on Post-Permission Mitigation Measures (paras 38–44).676 Hunterhuegh Crags,Northumberl<strong>and</strong>: after quarryingof rock outcrops in the earlyBronze Age this carving wasmade on the new surface. ©Archaeological Research Services Ltd7 Cheviot Quarry,Northumberl<strong>and</strong>: archaeologistsexcavating the interior of aBronze Age roundhouse that wasaccurately dated to the 10thcentury BC. © ArchaeologicalResearch Services Ltd8 View towards the visitor centre<strong>and</strong> wetl<strong>and</strong>s at AttenboroughQuarry, Beeston, Nottinghamshire,where much of the site hasbeen restored <strong>and</strong> is activelyused by community groups.© Tim Cooper, Arcus87

THE PLANNING PROCESSOverview22 The policies <strong>and</strong> proposals that are the basis ofthe Development Plan are contained in the RegionalSpatial Strategy <strong>and</strong> Local Development Frameworksappropriate to that area (which may, in the case of thosedocuments specific to minerals, be referred to as MineralDevelopment Frameworks or MDFs). All planningapplications must be determined in accordance withthe Development Plan unless material considerationsindicate otherwise. Consequently it is essential that thebest available archaeological information is used whenthe LDFs are being drafted <strong>and</strong> consulted upon. Inparticular, at the LDF stage the planning authorityshould seek archaeological input from local authorityarchaeological curators that will assist in identifying areasof potential archaeological sensitivity. If appropriatepolicy provision is not made when a LDF is draftedit makes protection of archaeological interests muchmore difficult later, when individual planning applicationsare considered.The development of the archaeologicalcomponents of LDFs is primarily a role for localauthorities to undertake, although mineral operatorsmay assist.23 At all phases, provision for archaeological work shouldfollow a question-led approach in which clear researchgoals are linked, wherever possible, to local, regional<strong>and</strong> national research agendas. At the pre-determinationstage, however, questions may initially relate to morebasic concerns such as the character, date <strong>and</strong> extentof archaeological remains to provide information ontheir relative importance. Later on it is particularlyimportant that any programme of work is linkedto regional research frameworks for the historicenvironment, <strong>and</strong> any other local research strategies orpolicies.The responsibility for this is shared betweenthe archaeological curator, consultant <strong>and</strong> contractor.Any programme of archaeological work will need tobe agreed by the local authority archaeological curator<strong>and</strong> approved by the mineral planning authority inadvance of commencement.Local Development Frameworks24 A new system for producing development plans wasintroduced in 2004.The principal policies against whichminerals planning applications are considered are nowcontained in the LDF (or MDF) in place of the old<strong>Minerals</strong> Local Plans. LDFs <strong>and</strong> MDFs are in turn madeup of a series of Local Development Documents(LDDs) that address specific aspects of l<strong>and</strong> use planningfor their area. Further detail on LDDs can be foundin PPS12 <strong>and</strong> the accompanying <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>(ODPM 2004).25 An important part of the new system is improvedstakeholder <strong>and</strong> public engagement in development planpreparation. Archaeological curators as key stakeholdersshould seek to ensure that they are involved in thepreparation of LDDs so that archaeological interestsare addressed.The planning authority should takeaccount of the advice provided by curators in draftingpolicies <strong>and</strong> proposals for the LDD. Ideally, areas ofknown archaeological potential should be flagged <strong>and</strong>considered in the LDD <strong>and</strong>, if possible, mapped, drawingon the best possible data available at the time. Paragraph15 of PPG 16 (DoE 1990) states that ‘developmentplans should include policies for the protection,enhancement <strong>and</strong> preservation of sites of archaeologicalinterest <strong>and</strong> of their settings.The proposals map shoulddefine the areas <strong>and</strong> sites to which the policies <strong>and</strong>proposals apply’. However, it must be recognised thatarchaeological knowledge of an area may not becomprehensive. By identifying areas of known potentialat the earliest opportunity the risks to archaeologicalassets, mineral operators <strong>and</strong> planning authoritiesare reduced.To ensure effective consideration ofarchaeological interests in the LDDs, it is important thatarchaeological curators have an in-depth knowledge<strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the local <strong>and</strong> regional archaeology<strong>and</strong> are appropriately resourced <strong>and</strong> supported todeliver archaeological advice.26 Table 1 summarises the input to the LDDs requiredof archaeological curators. Flagging of archaeologicallysensitive areas within LDDs is vital to protectingarchaeological interests <strong>and</strong> safeguarding developersfrom proceeding with expensive applications forsites that later present significant risks in relationto archaeological interests. Mapping at the LDDstage can often be broad-brush, however, <strong>and</strong> thedeveloper should therefore seek early advice fromthe archaeological curator.27 A useful way of providing high quality data tounderpin archaeological provision within a LDD isto map l<strong>and</strong>form units <strong>and</strong> then overlay them witharchaeological data sets derived from such sourcesas aerial photographs <strong>and</strong> geophysical survey.Sometimes referred to as a ‘resource assessmentexercise’, this approach, digitally integrated into anHistoric Environment Record (HER, also known as theSites <strong>and</strong> Monuments Record or SMR), allows areas of8

PHASE1Issues <strong>and</strong>OptionsACTIONS FORARCHAEOLOGICAL CURATORSSeek to ensure all issues associatedwith archaeology are brought tothe attention of the MineralPlanning Authority (MPA) throughearly dialogue.The MPA shouldensure that no proposals are putforward that would have anunacceptable impact onarchaeological interests.99 Aggregate extraction occurs indifferent ways. For example, hereblast-hole drilling is taking placeat Tunstead limestone quarry,Derbyshire. © Tarmac Ltd10 A restored whinstone quarrythat will be brought into publicaccess at Howick, Northumberl<strong>and</strong>.© Archaeological ResearchServices Ltd11 The screening <strong>and</strong> scopingphases provide an opportunityto flag the potential archaeologicalimpacts of a mineral developmentat the earliest stages of its planning.© Archaeological Research ServicesLtd2PreferredOptionsRespond to the MPA’s consultationmaking it clear which proposalswould have an impact uponarchaeological interests that wouldbe contrary to national or regionalor local policy.Where possible, putforward suggestions/alternatives forconsideration which would remedythe situation.3SubmissionRespond to the consultation notingif any of the submitted proposalsare ‘unsound’, ie that they do notpass one or more of the ‘tests ofsoundness’ set out in PPS12.Wherepossible, put forward suggestionsthat would make the policy orproposal sound from anarchaeological perspective.104SustainabilityAppraisal(integral toeach of thephases setout above)The MPA should ensure that itseeks the archaeological curator’sadvice to ensure the appraisal hasparameters that include thehistoric environment.11Table 1: Archaeological input to the Local Development Documents.archaeological potential as well as the age of differentl<strong>and</strong>forms to be explicitly identified in well-surveyedareas <strong>and</strong> to be inferred in others. Given that aerialphotography works better over some soils <strong>and</strong> typesof geology than others, additional data from techniquessuch as geophysical survey <strong>and</strong> fieldwalking can be addedto such digital maps. Research has shown that there is adirect link between certain types of l<strong>and</strong>form <strong>and</strong> kinds9

12 St Keverne, Cornwall: thisroad-stone <strong>and</strong> aggregate quarrydug into the cliffs on the Lizardpeninsula has its own jetty <strong>and</strong>road access.The surrounding fieldboundaries are prehistoric in origin.© Cornwall County Council13 This late 19th-century granitequarry on Bodmin Moor is anhistoric monument in its own right.121314In reworking the quarry, careneeds to be taken to conserve theshape <strong>and</strong> character of the ‘finger’dumps that are typical of thecontemporary tramming of waste.© Cornwall County Council14 View over Dowlow <strong>and</strong>Hindlow quarries, Derbyshire,on the Carboniferous Limestoneplateau. © English Heritage.NMRof archaeological <strong>and</strong> environmental remains (eg Bishop1994, Passmore et al 2002, Knight <strong>and</strong> Howard 2004,Waddington <strong>and</strong> Passmore 2006). In some instancesl<strong>and</strong>forms, such as alluvial terraces, may overlie oldersediments that contain earlier remains. Differentl<strong>and</strong>forms present different opportunities for thepreservation <strong>and</strong> evaluation of archaeological <strong>and</strong>palaeoenvironmental remains. Underst<strong>and</strong>ing thesedifferences can enable identification of areas of higher<strong>and</strong> lower sensitivity, which means in turn that theresponse to proposed developments can take thisinto account. Another useful predictive tool is theHistoric L<strong>and</strong>scape Characterisation (HLC) datamaintained by some HERs, although its value will dependon the scale at which the HLC data has been mapped.28 Easily accessible high quality map-based data allowsall stakeholders involved in mineral extraction to basetheir decision-making, strategic planning <strong>and</strong> mitigationstrategies on the same set of information. However,this kind of mapped evidence requires informedinterpretation by the archaeological curator beforeareas of archaeological potential can be securely linkedto relevant policies within the LDD. For that reasonit is essential to consult the local authority archaeologicalcurator before any development proposals are drawn up.Planning applications29 Table 2 summarises the archaeological input requiredduring each phase of the planning application process.Any programme of work needs to be agreed in advancewith the archaeological curator.Screening30 Seeking a ‘screening opinion’ from the local MineralPlanning Authority (MPA) is optional for the prospectivedeveloper, but nevertheless forms part of the statutoryprocess. If one is sought then the local authority mustprovide a response. It is important, therefore, that thelocal authority has sufficient information available to giveone within the prescribed time limit. It is advantageousfor the MPA to consult the archaeological curator at thisstage, if not before, to ensure that any issues of concernare raised before a screening opinion is issued. Certaintypes <strong>and</strong> scales of mineral development will require anEnvironmental Impact Assessment (EIA), together withan Environmental Statement (ES) that details its results(for further definitions of the EIA <strong>and</strong> ES see paragraph32 below).The Town <strong>and</strong> Country Planning Regulations(DETR 1999f) <strong>and</strong> Circular 02/99 (DETR 1999a) set outthe circumstances when planning applications require anEIA.The information contained in an ES will be taken10

PLANNINGPHASE1Screening2Scoping3Predetermination<strong>and</strong> EIAARCHAEOLOGICAL INPUTSScreening is a formal process whichdetermines whether or not aplanning application should beaccompanied by an EIA (in mostcases minerals extraction applicantswill submit one). A ‘screeningopinion’ must be provided bythe planning authority if this isrequested by the applicant. It isadvantageous for the MPA toconsult archaeological curatorsas part of this phase.This is the process of determiningwhat should be included in theEIA. Scoping will invariably identify:the need for an environmentalstatement on the historicenvironment, the elementswhich need to be considered(eg buried remains, earthworks,palaeoenvironmental remains,historic l<strong>and</strong>scape characteretc), appropriate methods forassessing the potential impactsof development, <strong>and</strong> the proposedmitigation measures. Archaeologicalcurators should be consultedby the MPA <strong>and</strong> the mineraldeveloper.The EIA process must becompleted before submission ofthe planning application. Duringthis phase a range of techniquesshould be used to collect sufficientdata to identify the significantarchaeological effects of thedevelopment, as well anyconsequent mitigation measuresthat may need to be designed.The starting point for the historicenvironment component of theEIA is typically a desk-basedassessment, from which otherpre-determination measuresmay follow.4Determination5PostdeterminationmeasuresThe chosen investigative techniquesshould meet clearly definedarchaeological objectives <strong>and</strong> besuited to the nature of thel<strong>and</strong>form <strong>and</strong> the type ofarchaeology anticipated.Archaeological curators should beconsulted by the MPA <strong>and</strong> themineral developer.At this stage a decision is takenon whether the development isto be approved, <strong>and</strong> what planningconditions or obligations in relationto the historic environmentshould be attached.The MPAshould obtain advice from thearchaeological curator beforecoming to a decision.The measures taken at this stagecould range from no further workbeing required, through excavation<strong>and</strong> recording (including specialistanalysis, publication <strong>and</strong> archiving),to preservation in situ ofarchaeological remains.Thearchaeological curator has the roleof monitoring any archaeologicalmitigation works.Table 2: Archaeological input to the planning application process.into account in determining the proposal. If applicantsconsider that their proposals are likely to require an EIAthey should seek guidance at the screening stage on theneed for an EIA (ie a ‘screening opinion’). All submittedplanning applications will be screened <strong>and</strong> applicantsadvised if an ES is required, if not already submitted.Scoping31 Before making a planning application, a developermay ask the planning authority for its formal opinionon the information to be supplied in the EnvironmentalStatement (a ‘scoping opinion’).This allows the developerto be clear about what the planning authority considersthe main effects of the development are likely to be<strong>and</strong> therefore the topics on which the ES should focus.The planning authority should consult its archaeologicalcurator at this stage to ensure that any issues of concernare raised at the earliest opportunity. Even if consultation11

15 An effective mitigationprogramme will ensure thatarchaeological remains are properlyrecorded so that the resultinginformation can enhance ourunderst<strong>and</strong>ing of the past, as inthe case of the Neolithic materialdiscovered here at Cheviot Quarry,Northumberl<strong>and</strong>. © Tarmac Ltd151616 Excavation of a Romancorn-drying kiln at Denham,Buckinghamshire. ©Buckinghamshire County Councilof the HER shows that no archaeological remains areknown from the application site, this does not necessarilymean that it is without significant archaeological potential.English Heritage may be a statutory consultee in certaincircumstances. PPG 16 (DoE 1990) states that earlyconsultation with historic environment curators is highlydesirable as a means of agreeing the methods to beused in all archaeological work beyond the scoping stage.The key questions that should be asked at this stage arewhat are the likely archaeological impacts <strong>and</strong> how canthese be mitigated?Environmental Impact Assessment <strong>and</strong>pre-determination measures32 If the scoping process has identified archaeologicalissues, archaeological investigation should be included aspart of an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) inorder to assess what impacts need to be addressed<strong>and</strong> how they can be mitigated.The historic environmentis an important consideration in any EIA.The basicstructure of the EIA process as defined by the EuropeanUnion Directive (85/337/EC updated 1997) has beenincorporated very closely into UK legislation througha series of regulations or ‘statutory instruments’.Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is a procedurethat ensures that the environmental consequences ofcertain projects are identified <strong>and</strong> assessed before anyauthorisation, such as a planning permission, is given.Proposals that must be subject to EIA are those whichare likely to have significant effects on the environmentby virtue of their nature, size or location. In practicemost planning applications for mineral extraction willrequire an EIA.The term ‘Environmental Statement’(ES) is often used to refer to the key document thatresults from the EIA information-gathering process.Thepreparation of the ES is often the point at which thepre-determination stage is formalised <strong>and</strong> this is where amineral developer's responsibilities formally commence.33 A useful set of guiding principles is set out inPLANARCH 2. PLANARCH is a partnershipestablished to further the integration of archaeologywithin the planning process in North West Europe .PLANARCH 2 identified good archaeological practicebased on experience of EIA implementation across partsof the EU.The operational principles are intended toprovide a rigorous, robust <strong>and</strong> reasonable framework forensuring that the historic environment is appropriatelytreated in the EIA process.They have been arrived atfollowing a review of current practice across parts ofEngl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> North West Europe as part of thePLANARCH project.12

TECHNIQUELOCALDEVELOPMENTFRAMEWORKPRE-DETERMINATIONPOST-DETERMINATIONPOST-EXCAVATIONANDDISSEMINATIONAerial photograph transcriptionArchaeological surveyDesk-based assessmentEvaluation trenchingExcavationFieldwalkingGeomorphological mappingGeophysical surveyPalaeoenvironmental analysisPost-excavation, archive<strong>and</strong> dissemination•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••Sediment coringStrip, map <strong>and</strong> sampleTest pitsWatching brief••••••••••••••••••Table 3: Relative frequency with which archaeological techniques are used at different phases of the planning process.34 No single technique exists that can identify allarchaeological remains.There is a range of establishedtechniques that is used to evaluate <strong>and</strong> recordarchaeological <strong>and</strong> palaeoenvironmental deposits (seeTechniques section below). Some of these allow thedetection of sites (eg aerial photography, fieldwalking,geophysics) while others are used to make a moredetailed record of structures <strong>and</strong> deposits (eg surveying<strong>and</strong> test pits). Evaluating an area deemed to bearchaeologically sensitive usually requires a combinationof techniques appropriate to the type of l<strong>and</strong>form <strong>and</strong>potential archaeology that may be encountered. Forexample, linear evaluation trenches are generally effectivefor finding continuous features such as field systems,enclosures, forts or large ring ditches (Hey <strong>and</strong> Lacey2001, 59). Conversely, they are poorly suited to findingdispersed, small or non-continuous remains such aspost-built buildings, pits or hearths.The quality of predeterminationarchaeological information requiredfor proposed mineral developments is a significantconsideration for developers <strong>and</strong> curators because thereis usually limited potential for amending permissions totake account of nationally important archaeologicalremains should these be found post-determination.35 Evaluation of the historic environment componentof a proposed development site is undertakenincrementally using an appropriate selection of thetechniques set out in Table 3 <strong>and</strong> based on effectivedialogue between the developer <strong>and</strong> curator.The firstpiece of pre-determination work is usually the deskbasedassessment.This is a crucial task <strong>and</strong> it is in theinterests of the mineral operator <strong>and</strong> local authoritythat it is undertaken by an appropriately qualified<strong>and</strong> experienced archaeologist. A good desk-basedassessment is a cost-effective investment that will reducerisk, whereas a poor assessment can lead to unexpectedcosts <strong>and</strong> delay. For certain types of mineral workings itis also important to consider the impact of any enablingworks (eg access roads, processing plants etc), thepotential for subterranean remains (eg old mineworkings) as well as potential Palaeolithic remains withinthe mineral body itself. Any programme of predeterminationarchaeological works should be agreedwith the archaeological curator <strong>and</strong> approved by themineral planning authority in advance ofcommencement.13

KEY PRE-DETERMINATIONTECHNIQUESAerial photographtranscriptionArchaeologicalsurveyDesk-basedassessmentEvaluationtrenchingFieldwalkingGeomorphologicalmappingGeophysical surveySediment coringTest pitsWHAT CAN IT DELIVER?Useful for discovering large sites.This may take the form of atopographic survey of upst<strong>and</strong>ingfeatures, a contour survey orrapid walkover survey to identifyany surviving upst<strong>and</strong>ing features.In-depth synthesis of existingdata <strong>and</strong> prediction of the typeof archaeological remains thatcould be expected to occur, orbe impacted upon.Invasive technique that allows theextent <strong>and</strong> character of subsurfaceremains to be identified<strong>and</strong> assessed.Rapid coverage over largeploughed areas virtually theonly technique that provides arecord of remains within theoverburden of a site.Establishes the nature <strong>and</strong> extentof l<strong>and</strong>forms <strong>and</strong> the associationsthey may have with particulartypes of archaeological remains.Rapid coverage over large areasnoting the potential presence ofburied archaeological remains.Rapid assessment of theexistence of buried sites,buried l<strong>and</strong> surfaces <strong>and</strong>organic deposits that may holdpalaeoenvironmental information.As evaluation trenching but onsmaller scale. Can also link fieldwalkingdata with buried features<strong>and</strong> record archaeological remainssurviving in the overburden.Determination36 Following one or more stages of pre-determinationworks, an informed decision is made by the planningauthority to grant or refuse planning permission. Ifpermission is granted, appropriate planning conditionsor obligations, such as Section 106 agreements, will beapplied. Permission may be granted subject to a rangeof conditions. Examples could include further evaluationwork, full archaeological recording or, on some occasions,the preservation in situ of nationally important remainsidentified during the pre-determination evaluation stage.On occasions no further action may be required otherthan the analysis <strong>and</strong> dissemination of results to date (foran example of model conditions see PPG 16 paragraph30 (DoE 1990) <strong>and</strong> DoE Circular 11/95). It is a keyprinciple of PPG 16 that there should be a presumptionin favour of preservation in situ of nationally importantremains <strong>and</strong> their settings, whether scheduled or not.In addressing the latter consideration the developer<strong>and</strong> curator also need to give consideration to thecharacter of the surrounding historic l<strong>and</strong>scape. In somecases preservation in situ may be beneficial for boththe protection of the archaeology <strong>and</strong> the developer,as the latter does not have to bear the cost of fullexcavation. Preservation in situ may be appropriatefor other remains that are considered to be ofsufficient importance.37 The criteria for assessing whether archaeologicalremains are of national importance are set out inAnnex 4 of PPG 16 (DoE 1990) together with anadditional criterion identified by English Heritage as‘amenity value’.The amenity value of a monument isassessed in terms of its visibility <strong>and</strong> its physical <strong>and</strong>intellectual accessibility.These criteria are currently underreview <strong>and</strong> further guidance can be expected. Otherfactors that should be considered are the state ofpreservation of the archaeological remains <strong>and</strong> thepotential for survival beneath the surface. Becauseall sites are unique, weighing up the significance ofarchaeological remains requires professional judgement.Post-permission mitigation measures38 Official guidance states that planning conditions,including those for post-permission archaeologicalmeasures, should only be imposed where they satisfyall of the following tests. In brief, all archaeologicalconditions at any stage in the planning processshould be:Table 4: Contributions of the archaeological techniques typically used at thepre-determination stage to establish the importance of archaeological remains.14

KEY POST-DETERMINATIONTECHNIQUESArchaeologicalsurveyExcavationMonitoringPalaeoenvironmentalanalysisStrip, map <strong>and</strong>sampleWatching briefWHAT CAN IT DELIVER?This may take the form of atopographic survey of upst<strong>and</strong>ingfeatures, a contour survey orrapid walkover survey to identifyany surviving features withsurface expression.Full recording <strong>and</strong>/or samplingof archaeological remainsover large or small areasbefore removal.This may include anarchaeologist visiting anextraction site on a regular basiswhen extraction is taking placeto monitor sediment or rocksections in order to identify <strong>and</strong>record archaeological featuresthat may be revealed.Reconstructs past human useof the environment through avariety of methods that includesampling organic sedimentsfor pollen, seeds, charred orwaterlogged wood, <strong>and</strong> indicatorspecies such as beetles, snailsor other organisms.Stripping the site to reveal theentire archaeological remainswithin a development area,planning them <strong>and</strong> thenselectively sampling to provideinformation sufficient tointerpret the site adequately.Ensures archaeologicalmonitoring (<strong>and</strong> recording ifnecessary) over a given area asit is stripped back under closearchaeological supervision.• necessary• relevant to planning• relevant to the development to be permitted• enforceable• precise• reasonable in all other respectsAny programme of post-permission archaeologicalworks should be discussed <strong>and</strong> agreed with thearchaeological curator in advance of commencement.Such a requirement usually appears as part of anarchaeological condition.39 Archaeological mitigation measures range from nofurther work, through full excavation to preservationin situ of archaeological remains.Typically they liesomewhere between two ends of the spectrum <strong>and</strong>involve a combination of preservation, excavation(ie recording) <strong>and</strong> perhaps long-term monitoring (seeTable 5). Because the choice of mitigation measuresrequires a long-term perspective, due considerationshould be given to ensuring that mitigation solutions aresustainable over the long term. In some cases this meansthat archaeological remains will be protected through‘preservation by design’. For example, if ground waterlevels need to be altered, this work will be designedin a way that prevents any waterlogged archaeologicalremains from drying out <strong>and</strong> thus being destroyed.Where remains are preserved in situ there may be aneed for long-term monitoring, <strong>and</strong> possible provision forfurther mitigation if preservation conditions deteriorate.40 A key part of post-permission mitigation is theassessment, analysis, archiving <strong>and</strong> dissemination ofinformation – sometimes referred to as the ‘postexcavationstage’ (Table 6). It is not only essential thatsuch work is factored into the cost of post-permissionmitigation but also that its level <strong>and</strong> scope is agreedwith the archaeological curator shortly after thefieldwork is complete. Later on there may be significantopportunities for developers to use interpretative,educational <strong>and</strong> outreach initiatives to engage withthe wider community <strong>and</strong> gain recognition for theirinvestment in the archaeological heritage.Table 5: Contributions of the archaeological techniques that are most typicallyused in the post-determination stage.15

TYPICAL POST-EXCAVATIONWORKPrimary archiveAssessmentAnalysisReport ProductionWHAT CAN IT DELIVER?This includes a stratigraphyreport detailing all archaeologicalfeatures <strong>and</strong> contexts <strong>and</strong>relating them to theirstratigraphic sequence <strong>and</strong> anyrelationships between features aswell as illustrations, photographsof the small finds <strong>and</strong>environmental samples <strong>and</strong>their accompanying registers.After the primary or site archiveis compiled certain categoriesof material that may providefurther information are rapidlyassessed to see whether theymerit a full analysis. For example,common finds that are assessedare pottery, flint tools,metalwork, skeletal remains,environmental samples <strong>and</strong>material that could beradiocarbon dated. Selectedsamples may be dated to providespot-dates on key deposits.If, after assessment, any materialis considered appropriate forfurther analysis then a morethoroughanalysis of the materialtakes place.This could include,for example, the acquisition ofradiocarbon dates, a report onthe pottery assemblage orreport on the environmentalremains from a site.Once the primary archive hasbeen assembled <strong>and</strong> anyassessments <strong>and</strong> analyses arecomplete a final integratedreport is produced that shouldsynthesise <strong>and</strong> interpret thearchaeological remains.ArchiveDisseminationThis includes the archiving <strong>and</strong>mounting of photographs <strong>and</strong>transparencies, the conservation<strong>and</strong> appropriate storage of smallfinds <strong>and</strong> the paper site archive.These should then be depositedwith an appropriate institution.The digital archive is normallysubmitted to the on-linedatabase of archaeological sites(OASIS).This may take a range of formsfrom a published academic paperor monograph to newspaper<strong>and</strong> magazine articles, publictalks, television <strong>and</strong> radioprogrammes, other mediacoverage, information panels,open days, school visits orschool packs, leaflets, guidedwalks <strong>and</strong> so forth.Table 6: Contributions of the key components of the post-excavation, archive<strong>and</strong> dissemination phase.41 Restoration is a key element of mineral extraction<strong>and</strong> one that has been carried out to good effect onmany sites, thereby improving the l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> thequality of life of local communities. It is important thatplans for quarry restoration are in keeping with thehistoric l<strong>and</strong>scape character of the site’s surroundings.In practice this has to be reconciled with a widerrange of interests that may also include biodiversity,geodiversity <strong>and</strong> recreation.16

TECHNIQUES42 The range of archaeological techniques describedbelow is not exhaustive, but simply provides an overviewof the more-commonly employed methods. Forconvenience they are described in alphabetical orderrather than in the sequence in which they will typicallybe employed in the planning process.The effectivenessof different archaeological techniques depends on thetype of l<strong>and</strong>form on which they are being used, the type<strong>and</strong> period of archaeology they are trying to locate orrecord, <strong>and</strong> in some cases even the time of year they areused. No single technique can provide all the information<strong>and</strong> it is therefore in the interests of both the developer<strong>and</strong> the local authority archaeological curator to agree asuite of techniques suited to the particular needs of thesite under investigation.43 The post-excavation stage of any programme ofwork is an important consideration <strong>and</strong> should includeprovision for the assessment, analysis, archiving <strong>and</strong>dissemination of the results including, where possible,to the general public.The contribution by the developershould be accorded due recognition whereverappropriate. A section on the post-excavation phaseis included below.44 When employing any archaeological technique,appropriate technical st<strong>and</strong>ards <strong>and</strong> guidance mustbe followed, including those set out by the Institute ofField Archaeologists (IFA) <strong>and</strong> English Heritage as wellas other guidance specific to the region or technique.45 In the following overviews reference is made tothe relative costs of each technique.These commentsare intended only as a guide to help provide a broadindication of the cost of the various techniques relativeto each other. It must be borne in mind, however,that this will always be proportionate to the scale<strong>and</strong> complexity of the site in question. In terms of riskmanagement more expensive techniques that providegood quality information can sometimes be more costeffective in the long run than cheaper but less reliableones that introduce a higher element of risk.Aerial photography46 Over the past hundred years, aerial photographyhas proved to be a very effective tool for discoveringarchaeological sites, although its effectiveness dependson the local geology, soil <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>-use regime. Largecollections of aerial photographs, taken both forarchaeological <strong>and</strong> non-archaeological purposes,are available for study <strong>and</strong> provide a rich source ofvaluable information.17 Cropmarks of ring ditchesbelonging to previously upst<strong>and</strong>ingBronze Age barrows in a fieldadjacent to flooded gravel pits nearWest Deeping, Cambridgeshire.© English Heritage.NMR17181918 A LiDAR image showing partof a Romano-British field system(right) near Halecombe Quarry,Somerset. Cambridge UniversityUnit for L<strong>and</strong>scape Modelling.© English Heritage19 Surveying of the principalcrushing mill at Hilton <strong>and</strong> Murtonlead mines, Scordale, Cumbria.© English Heritage17

47 Aerial photography can reveal archaeological sitesthat survive as upst<strong>and</strong>ing remains or earthworks,including those that are slight <strong>and</strong> difficult to observe atground level. Sites no longer visible at the surface may beidentified, under certain conditions, through differences inthe growth of plants <strong>and</strong> crops.These crop marks <strong>and</strong>parch marks are usually only recognised from the air <strong>and</strong>are particularly common in drought conditions. Sites canalso be recognised through soil marks, when ploughingbrings parts of archaeological deposits to the surfaceof the field.48 Analysis of aerial photographs from all readily availablecollections should be a normal part of any desk-basedassessment.The work should be undertaken by aspecialist archaeological air photo interpreter who will beable to provide accurate mapping <strong>and</strong> guidance on thetypes of features visible <strong>and</strong> the limitations of the results.The collections of aerial photographs held by theNational Monuments Record (Swindon) <strong>and</strong> the Unitfor L<strong>and</strong>scape Modelling (Cambridge University) shouldalways be consulted, as well as those available throughthe local planning authority.The results should becompared with available geomorphological data toidentify whether apparently blank areas may be dueto archaeological remains being more deeply buried<strong>and</strong> so less likely to be visible.49 English Heritage is undertaking a National MappingProgramme (NMP) to provide a synthetic analysis ofarchaeological features recorded from the air. The resultsfrom this can inform the Local Development Frameworkor be used in the pre-determination phase of theplanning application. In the areas already completedthis can provide a useful guide for planning purposes.Nevetheless it is still necessary to check whether newair photo information is available <strong>and</strong> whether moredetailedwork is needed for mitigation purposes. Severalaggregate resource assessment surveys have also usedthe NMP methodology to help strategic planning <strong>and</strong>enhance the respective HERs.50 Aerial photography can only partially reveal theextent <strong>and</strong> character of archaeological remains. Newtechniques such as airborne laser scanning (LiDAR) <strong>and</strong>multi-spectral imaging can be useful additional tools.Like geophysical survey, however, they should betreated as complementary techniques rather thanbe used in isolation.51 Aerial photography is a mid-range expense, buthighly cost-effective in terms of the return that can beexpected from analysis <strong>and</strong> transcription. For potentiallarge-scale, long-term developments considerationshould be given to commissioning archaeological flyingat specific times of the year when the soil moisturedeficit is at its maximum.Archaeological survey52 Traditional archaeological survey is a non-intrusivemethod for recording upst<strong>and</strong>ing archaeological remains.It is particularly useful for underst<strong>and</strong>ing constructionalrelationships <strong>and</strong> is used on earthwork sites <strong>and</strong> thosewith st<strong>and</strong>ing buildings or masonry. Surveys can take avariety of forms: the recording of upst<strong>and</strong>ing features,l<strong>and</strong>scape topography <strong>and</strong> contour surveys. If upst<strong>and</strong>ingremains are to be excavated it is st<strong>and</strong>ard practice toaccurately survey the site in advance of excavation. Inaddition, if l<strong>and</strong>scape character or the setting of a sitemay be disturbed by a development, then a survey ofthe surrounding area may be required.53 Surveys can often be enhanced by reference toaerial photographs that help show large features moreclearly, as well as the presence of buried features. Fieldsurveys may also be enhanced by the use of LiDAR data;depending on its resolution, this can very rapidly providedetailed contour information that can assist in pickingout subtle as well as more-clearly defined features. Itcan be particularly useful in relation to the rapid surveyof complex earthworks such as ridge <strong>and</strong> furrowploughing, deserted medieval villages, areas of woodl<strong>and</strong><strong>and</strong> features associated with previous mineral extractionor 20th-century military installations.54 Walkover survey is a rapid means of assessing theupst<strong>and</strong>ing archaeology <strong>and</strong> built structures of largeor inaccessible areas, such as woodl<strong>and</strong>. It comprisessystematically walking over a given area in order to plotall features onto a base map, usually with the aid of ah<strong>and</strong>-held global positioning system (GPS).55 Survey is a recording technique that can be employedeither pre or post-determination. It is a medium-expensetechnique that requires time in the field by a teamof usually two or more people depending on the sizeof the site. It can involve the use of specialist surveyequipment, GPS instruments, surveying software <strong>and</strong>drawing packages to produce scale drawings fromdigital output.18

Desk-based assessment56 A desk-based assessment (DBA) is defined bythe Institute of Field Archaeologists (IFA 2001b) as‘a programme of assessment of the known or potentialarchaeological resource within a specified area or site’.This involves a detailed <strong>and</strong> comprehensive assessmentof all the documentary evidence that can be accessedfor the development site <strong>and</strong> its immediate environs.Its purpose is to allow a well-informed judgment tobe made about the archaeological potential of thesite <strong>and</strong> the importance of any known remains.57 A DBA is frequently submitted to the planningauthority by the applicant in order to assist indetermining the need for further archaeologicalinvestigation. Archaeological curators should be consultedat the outset as to what is required in the DBA <strong>and</strong>will advise on the specification for the work.Thearchaeological importance of a site is assessed againstother comparable examples <strong>and</strong> is guided principallyby the criteria set out in PPG 16.58 A DBA is used to ‘identify the likely character,extent, quality <strong>and</strong> worth of the known or potentialarchaeological resource’ (IFA 2001b). In doing this, theDBA will need to provide a statement of archaeologicalpotential, which if necessary can be tested <strong>and</strong> refined byfurther assessment.The DBA will typically include <strong>and</strong>analyse information from a range of sources, including inthe first instance the HER, together with modern <strong>and</strong>historical maps <strong>and</strong> plans of the area, the NationalMonuments Record (NMR), Historic L<strong>and</strong>scapeCharacterisation (HLC) data, aerial photograph evidence,published literature <strong>and</strong> unpublished reports, geologicalinformation, place-name evidence <strong>and</strong> any literaturerelating to previous investigations on or near the site.59 Historic L<strong>and</strong>scape Characterisation (HLC) is atechnique for mapping <strong>and</strong> classifying the historiccharacter of the l<strong>and</strong>scape. Around 89 per cent ofEngl<strong>and</strong>’s countryside has been characterised at a macrolevel by an English Heritage supported programme,although HLC may also be undertaken at a detailed levelin order to address the specific requirements of theplanning process. It makes use of the sources typicallyconsulted in DBAs, but adds an historical interpretationof past <strong>and</strong> present l<strong>and</strong>scape patterns. HLC isexpressed via digital mapping as part of a GIS, normallysupported by associated texts <strong>and</strong> databases. As well asdocumenting what has already been identified HLC canallow the prediction of hitherto unrecorded componentsof the historic l<strong>and</strong>scape, including above-ground <strong>and</strong>buried archaeological remains.60 Desk-based assessments are relatively inexpensiveas they do not include any fieldwork other than am<strong>and</strong>atory site visit <strong>and</strong> walkover survey (see IFA2001b).They are undertaken during the predeterminationphase of the planning application.Because their information is crucial to the decisionmakingprocess the commissioning of a good DBAwill invariably be a sound investment.Evaluation trenching61 Evaluation is a ‘limited programme of non-intrusiveor intrusive fieldwork which determines the presence orabsence of archaeological features, structures, deposits,artefacts or ecofacts within a specified area or site’(IFA 2001d). It involves machine-stripping the overburdenfrom trenches spaced across the development areaor in targeted areas to define the nature, extent <strong>and</strong>importance of any archaeological remains. Evaluationtrenching must comply with the IFA’s St<strong>and</strong>ard <strong>and</strong>Guidance for Archaeological Field Evaluation (2001d).62 Each site should be considered on its specific merits<strong>and</strong> the design of trenching should follow a question-ledapproach that draws on expectations of the type ofarchaeology that may reasonably be encountered <strong>and</strong>of its likely location.The planning authority may requesta sample of the site’s area <strong>and</strong> the importance of thearchaeological remains within in, to be evaluated.Thesample size should be reasonable <strong>and</strong> appropriate (see<strong>CBI</strong> 1991 <strong>and</strong> commentary in Hey <strong>and</strong> Lacey 2001).This is because the purpose of evaluation trenching isto identify the potential of an area <strong>and</strong> the importanceof the archaeological remains within it, <strong>and</strong> not to sampleexcavate the site. Responsibility for ensuring appropriatelevels of evaluation trenching should be shared betweencurators, developers, consultants <strong>and</strong> contractors. Beforeplanning permission is granted the mineral planningauthority should be able to demonstrate that allreasonable steps have been taken to ascertain that noremains worthy of in situ preservation will be, or arelikely to be, disturbed by the proposed development.19

20 The study of previousarchaeological work <strong>and</strong> theexamination of old maps areclassic components of a desk-basedassessment. © ArchaeologicalResearch Services Ltd21 Information can also beacquired from examination ofhistoric drawings such as this1827 example showing granite202122quarrying at Haytor, Devon.Devon Library Service (WestcountryStudies Library)22 These evaluation trenches atBroadoak Quarry, near Ebchester,County Durham, were positionedfollowing a programme of intensivefieldwalking across the site.© Archaeological ResearchServices Ltd63 Although evaluation trenching has become a verycommon technique it can be more effective at findingcertain types of archaeological remains than others.Depending on the results of an evaluation, thearchaeological curator may decide that furtherinvestigation is necessary.Trenching will frequently bepositioned to investigate known or potential remainsidentified using other evaluation techniques.Trenching isparticularly effective at finding large structures, or linearfeatures such as ditches, pit alignments, enclosed sites,field systems <strong>and</strong> Roman roads. It can also result in thediscovery of smaller <strong>and</strong> more discrete features such aspit clusters, small post-built buildings <strong>and</strong> burials. If theselatter types of archaeological remains are expected thenother techniques should also be considered. Alternativelythey could be dealt with through post-permissionconditions. Interpreting the results from evaluationtrenching is of key importance. An arc of three smallpost-holes in a trench may, for example, indicate thepresence of a substantial settlement. It is typical forevaluation programmes to include a contingencyrequirement for additional or extended trenching toprovide a better underst<strong>and</strong>ing of any remains that areidentified. Combined with other evaluation techniquesevaluation trenching can offer an accurate, speedy <strong>and</strong>cost-effective means of finding remains that meritpreservation in situ <strong>and</strong> identifying other necessarymitigation measures.64 Trenching is a medium to high expense technique thatcan be very effective for locating <strong>and</strong> evaluating largesites, linear features or sites where certain typesof buried archaeological remains are anticipated.It requires a combination of mechanical excavation<strong>and</strong> limited archaeological investigation followed byassessment of any archaeological <strong>and</strong> environmentalremains that are revealed. It is used as part of thepre-determination phase of the planning application.20

Excavation65 An excavation is defined by the IFA as ‘a programmeof controlled, intrusive fieldwork with defined researchobjectives which examines, records <strong>and</strong> interpretsarchaeological deposits, features <strong>and</strong> structures <strong>and</strong>,as appropriate, retrieves artefacts, ecofacts <strong>and</strong> otherremains within a specified area or site (IFA 2001c).All excavation must comply with the IFA’s St<strong>and</strong>ard<strong>and</strong> Guidance for Archaeological Excavation (2001c).66 Full archaeological excavation of a site allows forpreservation by record. Although physically destructive,excavation is almost invariably the most informative fieldtechnique <strong>and</strong> is imperative when archaeological remainswould otherwise be destroyed. As well as allowing asite to be recorded <strong>and</strong> understood in its entirety,excavation tends to the most effective technique forgenerating positive publicity <strong>and</strong> public interest in a site.67 The excavation process follows a typical sequence:• Once the overburden has been stripped, all featuresare h<strong>and</strong>-cleaned <strong>and</strong> surveyed.This can includeextant features such as pits, post-holes, hearths <strong>and</strong>ditches, or spreads of artefacts within sedimenthorizons, such as scatters of stone tools, animal bonesor even log boats.• Each archaeological deposit <strong>and</strong> feature is usually fullyexcavated or sampled, drawn, levelled, photographed<strong>and</strong> surveyed.The fill of a feature is often sampled torecover smaller artefacts as well as botanical remainssuch as charred plant remains (for guidelines seeEnglish Heritage 2002). A record sheet for eachfeature <strong>and</strong> deposit is completed together withregisters of finds, samples, photographs <strong>and</strong> drawings.• Once excavation is complete the primary or sitearchive is moved to the office <strong>and</strong> any fragile findsare placed in a stable environment. Finds, samples,photographs, written <strong>and</strong> drawn records are thencollated ready for the Post-excavation stage (seesection below).68 Large scale excavation work should follow establishedpractice through the use of English Heritage’s MoRPHE(Management of Research Projects in the HistoricEnvironment, English Heritage 2006, the recentreplacement for MAP2) process <strong>and</strong> the IFA St<strong>and</strong>ard<strong>and</strong> Guidance for Archaeological Excavation (2001c).23 A large multi-phase Iron Ageroundhouse under excavation atHoveringham Quarry, Gonaldston,Nottinghamshire. © L Elliot24 Fieldwalking at Lanton Quarry,Northumberl<strong>and</strong>, revealed adiscrete focus of Neolithicoccupation on part of the site.© Archaeological ResearchServices Ltd23242525 Map showing the distributionof archaeological remainsin relation to differentgeomorphological units atthe Lanton Quarry site,Northumberl<strong>and</strong>. © ArchaeologicalResearch Services Ltd21

69 Excavation is usually employed as part of the postdeterminationphase of the planning process. Because itis labour-intensive <strong>and</strong> generates more post-fieldworkanalysis than other techniques, excavation tends tobe the most expensive type of archaeological work.Once the site has been stripped <strong>and</strong> the full extent ofarchaeological features has been established excavationcosts <strong>and</strong> time frames can normally be fixed so as tolimit further financial risk to the developer.Fieldwalking70 This is an important technique that should beconsidered for all potential quarry sites where removalof topsoil will occur.This is because fieldwalking allowstwo processes to be undertaken at the same time. Firstly,by collecting a sample of the surviving artefacts from thetopsoil a record is created of the archaeological resourcein the topsoil. For some periods such as the Late UpperPalaeolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic <strong>and</strong> Early Bronze Agethis may be all that is left of past human activity at thesite. Secondly, spatial plotting of artefacts found on thesurface can allow the location of potential sub-surfaceremains. Although this method is relatively inexpensiveit can yield good informative data. For best results itis sometimes worth having an area of l<strong>and</strong> speciallyploughed or harrowed, provided it has been ploughedin the past <strong>and</strong> there is no risk to upst<strong>and</strong>ing or buriedarchaeological remains. Fieldwalking usually needs tobe supported by other more invasive techniques,such as test pitting or evaluation trenching, in order tofurther define <strong>and</strong> characterise any surviving sub-surfacedeposits <strong>and</strong> the evidence for archaeological remainsin the overburden.71 Fieldwalking involves archaeologists systematicallywalking across ploughed fields searching the ground forartefacts.The closer together the walkers are placed themore accurate the survey will be <strong>and</strong> the greater thepotential to identify sites <strong>and</strong> assess potential risk. Innorthern Engl<strong>and</strong> intervals of 2–5 metres have beenfound to be most effective whereas in other areas,where flint is more common, spacings of perhaps 10mmay be more appropriate. Finds are bagged, numbered<strong>and</strong> plotted in so that each find can be accuratelylocated on a map.72 The most common finds are stone tools <strong>and</strong> pottery.Fieldwalking is therefore particularly useful for identifyingStone Age (Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) <strong>and</strong> Earlyto Middle Bronze Age sites, as well as Iron Age, Roman,medieval <strong>and</strong> post-medieval sites that sometimesproduce large quantities of well-fired pottery. Poorly firedprehistoric <strong>and</strong> early medieval pottery is rarely foundusing this technique.Where sites are identified by aerialphotography or geophysics, fieldwalking can be used toassess their date as well as to retrieve importantartefactual evidence that may not survive in the burieddeposits. It is sometimes worth considering including aformal programme of metal detecting (for st<strong>and</strong>ards onmetal detecting see Gurney 2003) across a field if it isconsidered there is potential for metalwork to survive.73 Fieldwalking is a relatively inexpensive technique thatallows for broad-brush archaeological prospection <strong>and</strong>characterisation of Stone Age <strong>and</strong> later l<strong>and</strong> use overlarge areas based on the patterning of stone tooldistributions. However, if significant quantities of finds areretrieved there may be additional costs for specialistanalysis of lithics (stone tools), ceramics <strong>and</strong>, more rarely,metalwork <strong>and</strong> coarse stone tools. Fieldwalking is mostcommonly employed in the pre-determination phaseof the planning application but the results from earliersurveys can usefully feed into the LDD. It is particularlyeffective for locating Stone Age archaeology whenundertaken at closely spaced intervals.Geomorphological mapping74 Geomorphological mapping can assist in thedesign of an evaluation programme. Detailed maps ofl<strong>and</strong>form units can be used to identify potentialpalaeoenvironmental remains, assess sediment units, aswell as to produce superficial <strong>and</strong> buried-terrain modelsthat can inform predictive models of sites <strong>and</strong> theirwider l<strong>and</strong>scape setting. Such work can reveal how thel<strong>and</strong>scape was formed <strong>and</strong> how it has been modifiedthrough time.This in turn allows prediction of thesurvival of remains of different periods at differentdepths, alongside an assessment of their likely stateof preservation <strong>and</strong> the type of techniques appropriatefor their evaluation.75 Geomorphological mapping usually requires aprogramme of fieldwork <strong>and</strong> survey by appropriatespecialists, supported by desk-based analysis of OrdnanceSurvey maps, geological maps, aerial photographs <strong>and</strong>data from remote-sensing techniques such as LiDAR.Mineral operators frequently conduct their owngeotechnical bore-hole testing <strong>and</strong> where possiblethis should be used to assist <strong>and</strong> complement thegeomorphological analysis for archaeological purposes.Geomorphological maps can be used as the basisfor l<strong>and</strong>form classification <strong>and</strong> these can informarchaeological expectations for an area <strong>and</strong> subsequentdecision-making.22

76 A typical application of geomorphological mappingmight involve augering across the development area tomap the depth <strong>and</strong> extent of a buried l<strong>and</strong> surface or toidentify waterlogged sediment traps <strong>and</strong> other organichorizons.The technique can also be used to determinethe location <strong>and</strong> depth of hillwash deposits <strong>and</strong> thenfollow up such identifications with evaluation trenchingto assess their archaeological potential.77 Field-based geomorphological mapping is a rapid,cost-effective <strong>and</strong> relatively inexpensive means ofanalysing environmental change <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>form evolution,as well as providing a platform for other evaluationwork.To maximise cost effectiveness, industry-requiredgeotechnical assessments <strong>and</strong> archaeologicalgeomorphological mapping should ideally be integrated.Together they can provide important information onpast l<strong>and</strong>scape development <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>-use by humanpopulations as well as generate data on earlier farmingpractices. Detailed mapping of extensive areas can begreatly facilitated by high-resolution remote sensingtechniques such as LiDAR, although these may add tothe cost of survey. Geomorphological mapping is typicallyemployed as part of the pre-determination phase of theplanning application although prior work can provideimportant information to the LDD.Geophysical survey <strong>and</strong> remote sensing78 Geophysical survey consists of a suite of non-invasiveground-based remote-sensing techniques that can aidthe discovery of buried archaeological remains bymeasuring different physical properties of the subsurface.The preferred methods for mapping shallow remainsare magnetometer <strong>and</strong> earth resistance survey, althoughground-penetrating radar (GPR) is sometimes used.English Heritage has prepared detailed guidance forthe deployment of these techniques (English Heritage,2008b).The archaeological curator <strong>and</strong> consultants willusually be able to use their local knowledge to commenton the likely effectiveness of the techniques in a givenarea <strong>and</strong> thus on whether or not they should beemployed.There may also be opportunities forintegrating archaeological prospection with broaderminerals-based geophysical survey.79 Geophysical survey can offer a relatively inexpensive<strong>and</strong> cost-effective means of testing large areas for thepresence of sub-surface remains. However, its ability tosuccessfully detect archaeological deposits is influencedby local site conditions such as geology, soil properties,the depth of the overburden <strong>and</strong> variations in soilmoisturecontent. Because geophysical techniquesdepend on a physical contrast between buriedarchaeological features <strong>and</strong> the surrounding medium,it is not always possible to detect features with fills similarto their host soils <strong>and</strong> geology. Modern disturbancefrom pipes <strong>and</strong> other services can also mask moresubtle responses to archaeological features. Even whencircumstances are favourable, small discrete featuressuch as post-holes may not be identified, althoughsurveying with higher than normal sample densitiescan increase the chances of detection. Alluvial <strong>and</strong>other types of superficial deposits, particularly at depthsin excess of a metre, present serious difficulties forgeophysical prospecting.80 Because the responsiveness of geophysical techniquesis conditioned by local ground conditions, a pilot surveylinked with coring or test pitting can help with thedevelopment of a reliable <strong>and</strong> efficient evaluationstrategy. Different geophysical methods are oftencomplementary in the information they provide aboutburied remains. Because of its speed, magnetometersurvey will often be the preferred initial technique,followed up by more closely targeted investigationsusing other methods. Geophysical survey is typicallya medium-expense technique; it is not labour intensivebut does require the use of specialist personnel <strong>and</strong>equipment. It is typically employed as part of the predeterminationphase of the planning application.81 In recent years an airborne remote sensing techniqueknown as LiDAR (Light Detection <strong>and</strong> Ranging) hasbeen used to create highly detailed models of the l<strong>and</strong>surface at sub-metre resolution. As the LiDAR surveyaircraft flies over the target area a pulsed laser beam isscanned from side to side, measuring between 20,000to 100,000 points per second to build an accurate,high resolution model of the ground <strong>and</strong> the featuresupon it.This information can assist aerial photographicinterpretation of upst<strong>and</strong>ing archaeological features aswell as slight natural features such as palaeochannels.In Engl<strong>and</strong> the Environment Agency has for severalyears used LiDAR for the production of terrain mapsfor assessing flood risk.They hold data for large areasof the country, concentrating on the coasts <strong>and</strong> rivervalleys, <strong>and</strong> this can be made available in .jpg formatto legitimate researchers subject to strict licensingagreements.23