Newsletter Vol.16 No.3 - ADEA

Newsletter Vol.16 No.3 - ADEA

Newsletter Vol.16 No.3 - ADEA

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

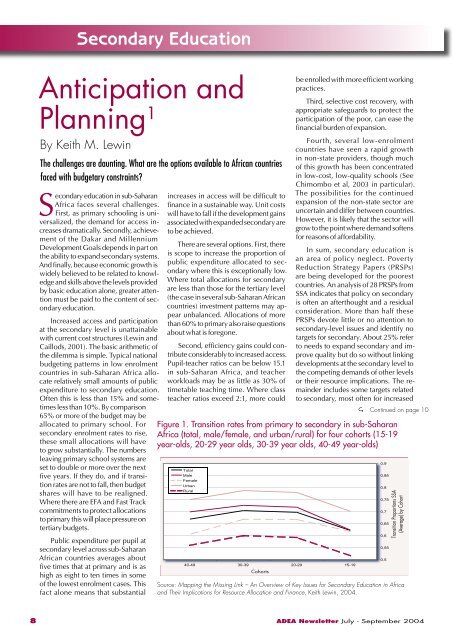

Secondary EducationAnticipation andPlanning 1By Keith M. LewinThe challenges are daunting. What are the options available to African countriesfaced with budgetary constraints?Secondary education in sub-SaharanAfrica faces several challenges.First, as primary schooling is universalized,the demand for access increasesdramatically. Secondly, achievementof the Dakar and MillenniumDevelopment Goals depends in part onthe ability to expand secondary systems.And finally, because economic growth iswidely believed to be related to knowledgeand skills above the levels providedby basic education alone, greater attentionmust be paid to the content of secondaryeducation.Increased access and participationat the secondary level is unattainablewith current cost structures (Lewin andCaillods, 2001). The basic arithmetic ofthe dilemma is simple. Typical nationalbudgeting patterns in low enrolmentcountries in sub-Saharan Africa allocaterelatively small amounts of publicexpenditure to secondary education.Often this is less than 15% and sometimesless than 10%. By comparison65% or more of the budget may beallocated to primary school. Forsecondary enrolment rates to rise,these small allocations will haveto grow substantially. The numbersleaving primary school systems areset to double or more over the nextfive years. If they do, and if transitionrates are not to fall, then budgetshares will have to be realigned.Where there are EFA and Fast Trackcommitments to protect allocationsto primary this will place pressure ontertiary budgets.Public expenditure per pupil atsecondary level across sub-SaharanAfrican countries averages aboutfive times that at primary and is ashigh as eight to ten times in someof the lowest enrolment cases. Thisfact alone means that substantialincreases in access will be difficult tofinance in a sustainable way. Unit costswill have to fall if the development gainsassociated with expanded secondary areto be achieved.There are several options. First, thereis scope to increase the proportion ofpublic expenditure allocated to secondarywhere this is exceptionally low.Where total allocations for secondaryare less than those for the tertiary level(the case in several sub-Saharan Africancountries) investment patterns may appearunbalanced. Allocations of morethan 60% to primary also raise questionsabout what is foregone.Second, efficiency gains could contributeconsiderably to increased access.Pupil-teacher ratios can be below 15.1in sub-Saharan Africa, and teacherworkloads may be as little as 30% oftimetable teaching time. Where classteacher ratios exceed 2:1, more couldbe enrolled with more efficient workingpractices.Third, selective cost recovery, withappropriate safeguards to protect theparticipation of the poor, can ease thefinancial burden of expansion.Fourth, several low-enrolmentcountries have seen a rapid growthin non-state providers, though muchof this growth has been concentratedin low-cost, low-quality schools (SeeChimombo et al, 2003 in particular).The possibilities for the continuedexpansion of the non-state sector areuncertain and differ between countries.However, it is likely that the sector willgrow to the point where demand softensfor reasons of affordability.In sum, secondary education isan area of policy neglect. PovertyReduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs)are being developed for the poorestcountries. An analysis of 28 PRSPs fromSSA indicates that policy on secondaryis often an afterthought and a residualconsideration. More than half thesePRSPs devote little or no attention tosecondary-level issues and identify notargets for secondary. About 25% referto needs to expand secondary and improvequality but do so without linkingdevelopments at the secondary level tothe competing demands of other levelsor their resource implications. The remainderincludes some targets relatedto secondary, most often for increasedFigure 1. Transition rates from primary to secondary in sub-SaharanAfrica (total, male/female, and urban/rural) for four cohorts (15-19year-olds, 20-29 year olds, 30-39 year olds, 40-49 year-olds)TotalMaleFemaleUrbanRural40-4930-39Cohorts20-2915-19 Continued on page 100,90,850,80,750,70,650,60,550,5Transition Proportions SSA(Average) by CohortSource: Mapping the Missing Link – An Overview of Key Issues for Secondary Education in Africaand Their Implications for Resource Allocation and Finance, Keith Lewin, 2004.8 <strong>ADEA</strong> <strong>Newsletter</strong> July - September 2004