Floppy-tail Syndrome:

Floppy-tail Syndrome:

Floppy-tail Syndrome:

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Feature – Crested Gecko<strong>Floppy</strong>-<strong>tail</strong><strong>Syndrome</strong>:a problem which could endanger thecaptive population of crested geckosAndy Tedder considers a serious and misunderstoodhealth issue surrounding these popular lizards whichis becoming increasing prevalent, and explains whatshould be done to tackle the problem.Perhaps the most over-lookedand under-estimated conditionthreatening both the health ofindividuals and the ‘fitness’ of the captivecrested gecko (Rhacodactylus ciliatus)population today is floppy-<strong>tail</strong> syndrome(FTS). The <strong>tail</strong> is hyperextended in affectedindividuals, which means that it rotatesfreely, and, in extreme conditions, hangsat an angle of 90° perpendicular to thebody. It poses the risk of serious muscleand bone damage to geckos sufferingfrom this condition, and also has thepotential to have a serious impact on thecaptive ‘gene-pool’.The crested gecko <strong>tail</strong>The <strong>tail</strong> of the crested gecko, compared withother members of its genus Rhacodactylus,possesses some unique features, whichmake it highly specialised. Firstly, andperhaps most importantly is the presence oflamellae on the <strong>tail</strong> tip, which aid with gripin a similar fashion to the enlarged toe padsof geckos. In addition, the <strong>tail</strong>’s prehensilecapabilities allow this appendage to act asa fifth limb, helping the gecko to climb andbalance more effectively. It is very importantto note that both of these characters areprobably difficult to evolve.The third trait that this appendagepossesses which is of significance in thiscontext is caudal autotomy - the ability to‘shed’ the <strong>tail</strong> when threatened. Althoughthis trait is a common and well-documentedin many gecko species, the <strong>tail</strong> of crestedgeckos will not regrow if it is lost. This ishighly significant, and probably reflectsThe common theoriesA number of ideas have been putforward to explain this condition, asoutlined below.1. “The pelvis isn’t designed tosupport the weight of a <strong>tail</strong>” – thisis a very common suggestion as tothe reason why this species developsFTS in captivity. There is of coursea major problem with this, namely:the <strong>tail</strong> of crested geckos is a highlyspecialized, derived (as opposed toancestral) character, and as such islikely the product of many hundreds ofthousands (if not millions) of years ofevolution. To suggest that selection fora trait like this could occur at the sametime as selection for reduced musclecapability required to support it is clearlyexceedingly unlikely.2. Partial caudal autotomy – thistheory suggests that incomplete ‘loss’of the <strong>tail</strong> results in fracturing of themuscles only, thus significantly reducingthe animal’s ability to control its weight.In situations where the animal spendslarge amounts of time facing towardsthe ground, the <strong>tail</strong> will be able to‘hang’, causing the hips to tilt. Overprolonged periods, this will then resultin the associated hip damage. Whilethis theory IS plausible, it does not fullyexplain the sheer number of caseswhich have been recorded, and has yetto be demonstrated in any veterinarysituation. It is also likely that for muscledetachment to occur, the blood supplywould be lost and so the <strong>tail</strong> would likelydeteriorate rapidly, as dry gangrene setin.3. A symptom of metabolic bonedisease (MBD) – calcium plays a vitalrole within the body of all reptiles, andis involved in both bone maintenanceand muscle function. With this is mind,it would seem plausible that MBD couldplay a role in the development of FTS.However, it would appear to be quiteunlikely that the bone density of only thepelvis would be affected, and not themore commonly affected regions likethe limbs and lower jaw. X-rays also showthat bone density throughout the bodyis not being affected, and so calciummetabolism, while able to play a role inFTS is not likely to be the primary cause.This means that of the theoriesregularly suggested as causes of FTS incrested geckos, none of them really fullyexplains the phenomenon. Howeverthey do offer some insight into whatthe potential cause is, and how it maycontinue to affect the captive populationof this species in the future.July 2010 17

the gecko’s inability to replicate the veryspecialised structure of the <strong>tail</strong> itself at thetip. Unlike the situation with many otherspecies, the <strong>tail</strong> can only be lost in asingle position, again suggesting that thisis not an ancestral state, but a derivedor evolved trait.The symptoms of FTSAs mentioned briefly above, the mostcommon sign of FTS is hyperextensionor ‘floppyness’ of the <strong>tail</strong>. This part of thebody will often be seen hanging slightlyto the side, or most notably, hangingperpendicular to the body when the animalis itself upside down (or facing the ground).Other symptoms which often accompanythis problem include slight ‘lumps’ or‘depressions’ around the pelvic region,although these are not really conclusive.In severe cases though, clear damage tothe pelvis can be seen. Many sources willsuggest that a general weakening of the<strong>tail</strong> muscles characterizes FTS, and thusthe <strong>tail</strong> will no longer be able to grip. This,however, is not really true. The musclesinvolved in the prehensile action of the <strong>tail</strong>are seemingly not involved in FTS, and <strong>tail</strong>functionality is generally unaffected.Genetic fixation of reducedpelvic bone density.As many of you will know, crested geckoswere considered to be extinct until asrecently as 1994, reflecting a seriouspopulation decline. The captive population- which although now widespread - isbased on relatively few individuals. One ofthe potential pitfalls when populations gothrough a ‘bottleneck’ like this, a seriouspopulation decline with correspondinglyreduced genetic diversity, and then apopulation increase.In other words, animals that wouldpreviously not have been able to competefor a mate due to health issues, are able toBreeding affected animalsIt would perhaps appear to be a littlenaïve to suggest that this character ISfixed within the ‘gene pool’ , althoughwe see enough cases to suggest that itIS fixed in certain genetic lines. However,the most worrying thing for the futureis that it is likely that this could happento the entire captive population withcontinued breeding of individuals whichdisplay the FTS phenotype, (ie showingsigns of the condition). I continually hearpeople suggest that FTS will not affectthe chances of your animal breeding.Unfortunately I consider this VERY pooradvice for several reasons: If the bone density of the pelvisis low, then damage to the bone andmuscle tissue can and will arise fromprolonged exposure to FTS. This pelvicdamage is likely to impair a female’sability to pass eggs, greatly affecting therisk to health from breeding. Breeding individuals with reduced‘fitness’ can lead to problems generallywith the health of the offspring. Breeding individuals with a trait thatis likely to be genetically linked will onlyincrease the number of individuals inthe population that carry the trait. Thisessentially means that you are damagingthe ‘gene pool’ by allowing ‘less fit’individuals to contribute (and this is NOTrestricted to FTS, it goes for all reduced‘fitness’ characters).The final reason in the list above ispotentially the most potent reason notto breed individuals with FTS. You trulyrisk damaging the future of the speciesin captivity by breeding any animal thatexpresses a phenotype with reduced‘fitness’. I cannot stress enough how badthis will be for this species in captivity ifpeople continue to do so.successfully breed and pass their geneticmaterial on to further generations. Thiscan be a real problem, especially if thesereduced ‘fitness’ individuals are mating withother reduced ‘fitness’ individuals. Suchpairings can essentially lead to the fixationof these reduced ‘fitness’ traits in theClear pelvic tilt, with the <strong>tail</strong> no longerparallel to the body. © Annette Moore.18 Practical Reptile KeepingWhen horizontal, the <strong>tail</strong> lies to the side,out of the animal’s control. © Annette Moore.A pelvic ‘depression’ can be seen, and the<strong>tail</strong> does not hang correctly. © Jaclyn Linge.

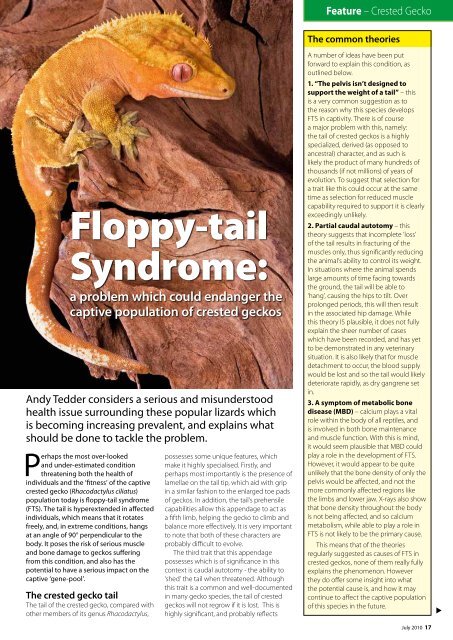

Feature – Crested GeckoIn this case, the <strong>tail</strong>is hanging at 90°perpendicular tothe body.population.In the case of the crested gecko, it isentirely possible that individuals with pelvicbone density lower than that required tomaintain <strong>tail</strong> weight at certain angles werenot at a selective disadvantage (as would beexpected under normal circumstances) dueto their small population size.This theory follows in the footsteps ofthe first suggestion above that perhaps“the pelvis wasn’t meant to support the <strong>tail</strong>weight”, although this is counter intuitive.However, if fixation of a negative character isinvolved because of necessary inbreeding,then this suggestion becomes a little moreplausible. Furthermore, it is also quite likelythat a slight calcium deficit would mean thatthe pelvis, with its already low bone density,could be the first area affected by the earlysymptoms of MBD.Taking individuals with reduced ‘fitness’into captivity and again being forced toA healthy crestedgecko climbingaround its quarters.Are crested geckos the onlyspecies affect by FTS?Unfortunately the answer to thisquestion is NO. However, for otherspecies, the reason for FTS are easilyunderstandable, and DO relate tocalcium metabolism, or to be morespecific, too little dietary calcium beingfully utilized. Again, the best course ofaction if you think your animal may besuffering is to seek veterinary advice.breed genetically related animals dueto low numbers is likely to increase theprobability of fixation. (In this case, allanimals which share the negative characterstate are related, regardless of the siblingstatus). All the offspring produced willtherefore share the trait too, and it has thepotential to become a permanent fixture inthe captive population.What should I do if my animalhas FTS?The first port of call when you notice thesymptoms of FTS is to seek the advice of aveterinarian that specializes in reptiles. Thiscannot be overlooked. You need to knowthe severity of the case, and the overallbone density of the animal in case thereare further husbandry issues which needaddressing. The vet will likely offer you anX-ray for this purpose, and I would highlysuggest that you agree.The results of the X-ray will allow youto assess accurately whether the gecko’scalcium metabolism is adequate, or whetheryou need to introduce further dietarycalcium and a source of UVB to prevent thecondition worsening. In extreme cases thevet can suggest amputating the <strong>tail</strong> in orderto prevent further stress to the pelvis. Inmy opinion, this is an excellent strategy forpreventing further physical damage to theanimal, and should be considered in thesecases. I would also suggest that people donot try to induce caudal autotomy in theiranimals however, as if carried out incorrectly,it can lead to serious health issues.In terms of vivarium management, itis often suggested that glass vivariumssomehow increase the incidence of‘hanging upside down’ or ‘facing theground’. I have no reason to think thisIS the case, however many people willrecommend dense planting of theenclosure to prevent the <strong>tail</strong> ‘flopping’over. While this may prevent immediatedamage to the animal, it perhaps masks thephenotype of FTS in the animal, increasingthe chances of passing it to the nextgeneration. ■*Andy Tedder is an enthusiastic breeder of geckos,with a keen interest in their genetics. You can find hisweb site at www.glasgowgecko.co.ukJuly 2010 19