Gourley TCCC and CLS Army May 2010 - Health.mil

Gourley TCCC and CLS Army May 2010 - Health.mil

Gourley TCCC and CLS Army May 2010 - Health.mil

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

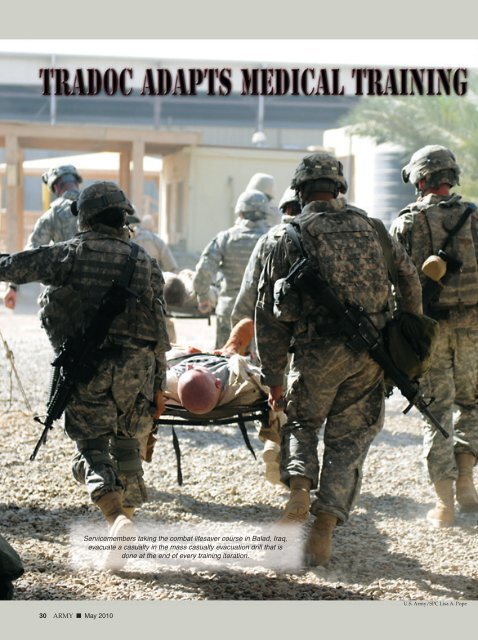

Servicemembers taking the combat lifesaver course in Balad, Iraq,evacuate a casualty in the mass casualty evacuation drill that isdone at the end of every training iteration.U.S. <strong>Army</strong>/SPC Lisa A. Pope30 ARMY ■ <strong>May</strong> <strong>2010</strong>

U.S. <strong>Army</strong>/SPC Lisa A. Pope U.S. <strong>Army</strong>By Scott R. <strong>Gourley</strong>s noted by LTG Mark Hertling,deputy comm<strong>and</strong>ing general, InitialMilitary Training, U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Training<strong>and</strong> Doctrine Comm<strong>and</strong>, inthe March issue of ARMY, themedical community is revising the <strong>Army</strong>’stactical combat casualty care (TC3) trainingbased on extensive combat experience, adaptingmany of the most critical tasks involvinghemorrhage <strong>and</strong> traumatic battlefield injuries.“TC3 is a field that originated in a lot ofunits—particularly the Rangers <strong>and</strong> SpecialForces, but also in conventional line units—where the medics <strong>and</strong> surgeons, going backas far as the conflict in Somalia, were noting‘lessons learned’ in the way that we first respondedto casualties, prior to when theyreached a fixed medical facility,” explainedTRADOC surgeon COL Karen O’Brien,Medical Corps. “If you think about the wayyou respond to trauma on the battlefieldcompared to the way you would do it besidean American highway, it’s quite different.There are tactical considerations that don’tAbove, 1LT Eliza Wick, battalion personnel officerfor Headquarters <strong>and</strong> Headquarters Company, 82ndBrigade Support Battalion, 3rd Brigade CombatTeam, 82nd Airborne Division, puts a tourniquet onthe leg of PVT Matthew Wright during practicalcombat exercises at the tactical combat casualtycare (TC3) class at Contingency Operating BaseSpeicher, Iraq. Left, students in the combat lifesavercourse taught at the Tricia L. Jameson combatmedic center, Balad, Iraq, run into action during themass casualty evacuation drill in September.<strong>May</strong> <strong>2010</strong> ■ ARMY 31

Soldiers at FortSill, Okla., take IV(intravenous)training. Since theintroduction ofcombat lifesavertraining two yearsago, soldiers’medical traininghas aligned moreclosely withtactical combatcasualty care.U.S. <strong>Army</strong>come into play in civilian medicine: things like maintainingsecurity when you are being attacked, in addition tobeing able to care for the casualty; things like teaching soldiersthat just because they are wounded doesn’t meanthat they shouldn’t keep shooting back <strong>and</strong> making surethey are neutralizing the enemy if they are able to. As a result,a lot of those tactical considerations started beingtaught to medical folks <strong>and</strong> to junior leaders in the smallunits that would be helping respond to casualties.”Noting that early activities also included reviewingdata from previous wars, she said, “What theyfound was that often after a war there would besome lessons learned that might be forgotten. An exampleof one of those was tourniquets. If you think about it, wehave been using cravat <strong>and</strong> belt-type tourniquets eversince the Revolutionary War. Yet there was data from earlierwars that showed that tourniquets of that nature didn’twork very well. On top of that, there was a lot of concernabout using tourniquets because people thought that ifyou cut off circulation to an extremity for too long, youwould lose that extremity. Based on the data collected inprior conflicts, however, we were able to start putting togetherthe facts, which showed that tourniquets that workactually save lives. So a lot of development occurred in theScott R. <strong>Gourley</strong>, a freelance writer, is a contributing editor toARMY.early 2000s to identify a good, functionaltourniquet that could be issuedto every soldier <strong>and</strong> put into the newimproved first-aid kits.“We think that doing that can nowbe credited with more than 1,000 livessaved,” COL O’Brien added. “Additionalresearch has also shown thatthere have been no bad outcomes onthe basis of using tourniquets. We alsoknow that there is still some hesitationin first responders to apply a tourniquet.So they often wait longer thanthey should, <strong>and</strong> sometimes peopledie because they don’t have a tourniquetput on in time. As a result, westill have some potential survivorswho die. The time to intervene to preventthese deaths is in the first 5 to 10minutes.”That analysis of battlefield lessonshad also prompted a significant revisionof medical aspects of basic combattraining, with the introduction ofcombat lifesaver training in <strong>May</strong> 2007.Among the memorable changes formany new soldiers at that time wasthe new requirement to successfullyinstall an IV [intravenous] needle withsaline bag lock.“As we started to teach all soldiers combat lifesavertraining, we started to modify that combat lifesaver curriculumto align it with principles of tactical combat casualtycare,” COL O’Brien said.Casualty analysis remains a dynamic process, however.COL O’Brien added, “One of the things they learned asthey continued to look at potentially survivable deaths <strong>and</strong>the causes behind them: Some of those causes were‘tourniquetable’ injuries. Others involved compressiblehemorrhage, which has led to the development of newspecial b<strong>and</strong>ages that have material on them to preventbleeding. And there was another area that evolved, noncompressiblehemorrhage—hemorrhage to the torso, likeinternal bleeding in the lungs or abdominal area. You can’treally put a tourniquet on that or compress that.”She continued, “What they found in those situations wasthat when you get a lot of IV fluid early on, it’s actuallybad for that type of trauma. First, it raises your blood pressure,which can blow off a clot that is forming inside thearea that can’t be reached, <strong>and</strong> all of that data coming fromthe Joint Theater Trauma Registry has shown that we wantto keep a lower blood pressure in some of those patients.Second, all of that extra fluid can dilute your blood’s abilityto clot naturally.”The concern about the noncompressible trauma wascompounded by the concern regarding remaining delaysin installing tourniquets.32 ARMY ■ <strong>May</strong> <strong>2010</strong>

SPC ChaseCarman, a medic<strong>and</strong> TC3 instructor,shows soldiers howto load a casualtyat the 82ndAirborne Divisiontroop medical clinicon ContingencyOperating BaseSpeicher.U.S. <strong>Army</strong>“Often first responders were focused on starting the IV,thinking that the IV was the lifesaving intervention,” COLO’Brien said. “In fact, there is really no data to show thatgetting an IV in the first 5 to 10 minutes is going to saveanybody’s life. It’s not that IVs are bad in the long run. It’sthat the priority of what should happen in the first fewminutes should be geared toward stopping bleeding.”Based on the analysis of all the data, the Committee onTactical Combat Casualty Care hadrecommended that the <strong>Army</strong> stop insertingIVs during the “care underfire” phase of medical treatment—primarilythe first few minutes after beingwounded.As a result, GEN Martin E. Dempsey,TRADOC comm<strong>and</strong>inggeneral, made the decision tosuspend IV training in basic combattraining in September 2009. Followingadditional analysis, a new medicaltraining support package was releasedin January <strong>2010</strong>.“We have changed the training toplace more emphasis on mastery ofbleeding control,” COL O’Brien said,adding that another area of emphasisin the new program involves fa<strong>mil</strong>iarizingsoldiers with the importance ofbeing evaluated after exposure to blasteffects. “If you’ve been in a vehicle exposedto a blast, within 50 meters of ablast, in a structure hit by a blast, orhave any kind of direct blow to yourhead or loss of consciousness, youneed to be evaluated by a medical professional,whether by a 68W [<strong>Army</strong>combat medic] or at an aid station,”she explained. “But you do need to beU.S. <strong>Army</strong>/Rodney Jacksonevaluated, <strong>and</strong> possibly allowed to rest for 24 hours, becauseif you get that rest early on, it allows your ‘harddrive’ to reset. But if you don’t get that rest <strong>and</strong> you driveon, then you could have lingering problems for months.”Another example of coordination across the <strong>Army</strong> medical<strong>and</strong> training communities during this same period isthe release of the new <strong>Army</strong> field medical card, alsoknown as the TC3 card, in individual first-aid kits.SGT PatrickMalone, C Troop,2nd Squadron, 14thCavalry Regiment,2nd BrigadeCombat Team, 25thInfantry Division,demonstrates howto apply thecombat applicationtourniquet during abilateral exercise atCamp Bundela,India.<strong>May</strong> <strong>2010</strong> ■ ARMY 33

Soldiers from the82nd AirborneDivision practiceloading a casualtyinto a paratroopermedical platformvehicle duringpractical combatexercises at theTC3 class at themedical clinic atContingencyOperating BaseSpeicher.“The field medical card is the card identifying you whenyou are a casualty,” COL O’Brien said. “Under our old system,that card was initiated once you entered the medicalsystem. So we really weren’t capturing a lot of data aboutwhat was actually happening at the level of the first responder,before someone entered the evacuation system:things like what time your tourniquet was applied or whatother lifesaving measures were carried out by the first responder.We had a great joint theater trauma registry thatwas capturing care after someone was further along in themedical system, but we didn’t have that early-on data. Thenew card is aligned with TC3, allowing the data to be capturedvery early, <strong>and</strong> also to assist us in analyzing data <strong>and</strong>immediately responding to lessons learned as we continueto refine the field of TC3—as we work to whittle away theapproximately 20 percent of combat fatalities that we believeto have been potentially survivable.”The removal of the IVs from the combat lifesaver bags—fielded per AR350-1 at a level of one per squad—has alsoallowed the fielding <strong>and</strong> related training of new hypothermia-prevention/warmingblankets.“When you lose a lot of blood, even if it is 100 degreesoutside, you get cold,” COL O’Briensaid. “If you get cold, your blood stops clotting.You also have a higher likelihood of dying from othercomplications. So these new blankets will help keep peoplewarm during the evacuation process, again bolstering theirsurvivability.”Other changes in the new medical training supportpackage include training in tactical movement of casualties<strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong>ed tactical scenario training.Another recent adjustment in Initial Military Training involveshearing protection <strong>and</strong> starting to train soldiers touse the new combat arms earplugs.“We are using an innovative approach developed bysome of our audiologists, bringing the training out to therange, so that when soldiers have their first basic riflemarksmanship, they will also be issued the earplugs <strong>and</strong>train with them at that range,” COL O’Brien said. “Nowthey will be using them right after they train with them. Wehave also worked with our safety colleagues to incorporatehearing protection into the safety briefings at the ranges, tyingthose things together. Since hearing loss is the top reasonfor VA [Department of Veterans Affairs] claims fromsoldiers, we think this will have a huge benefit.”In parallel with the new medical training efforts, theTRADOC surgeon is also involved with issues surroundingsleep deprivation. “I have been reviewing a lot of thematerial currently available, <strong>and</strong> we are looking at betterways to educate the force about the importance of sleep.We are looking at how to make our <strong>Army</strong> more resilient,<strong>and</strong> sleep is an important component of that,” COLO’Brien said. Acknowledging that the sleep-deprivationawareness <strong>and</strong> education campaign has to overcome a traditionalservice approach of digging deep <strong>and</strong> driving on,she added, “The old doctrine for sleep was that you shouldget a minimum of three hours a night. Last year we releaseda new field manual, FM 6-22.5 Combat <strong>and</strong> OperationalStress Control Manual for Leaders <strong>and</strong> Soldiers, whichsays that there is not a minimum number of hours, that weneed to strive for 7 to 8 hours of sleep, <strong>and</strong> any time youfall below that for any significant number of days, yourfunctions will start to be compromised.” ✭U.S. <strong>Army</strong>/SSG Bronco Suzuki34 ARMY ■ <strong>May</strong> <strong>2010</strong>

![Eye Injury Prevention Month Fact Sheet [PDF 3.64 MB]](https://img.yumpu.com/28543556/1/190x245/eye-injury-prevention-month-fact-sheet-pdf-364-mb.jpg?quality=85)