Aperçus Quarterly 1.3

Aperçus Quarterly 1.3 - Apercus Quarterly

Aperçus Quarterly 1.3 - Apercus Quarterly

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Aperçus</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong><strong>1.3</strong>

Issue <strong>1.3</strong>Melodie BoltThe Science Fiction of Blues within Blue Eyes 6with a nod to Frank HerbertJerry Springer’s Audience 7Boyd BensonAbby MurrayTo Say the Wind is Another ThingSoldier’s Wife Writes PoemI am Myself But No One KnowsI am Not Lucky: a Sestina891011Jan BottiglieriCastle Metals(a cebu)AlphabetDear Mr. Spock:121314Kara ArguelloTop Thrill Dragster15Robert PeakeBritish Matches16Juan DelgadoFor AnnaStanding Water1718Lisa CoffmanNot Choosing OtherwiseLight Comes at Me SidewaysThe Past TensePoem As Insect, Poem As Bird19202122LisaCoffman23

Issue <strong>1.3</strong>Andrew Stark Olive25InterviewsPaying Attention To It All WithLisa CoffmanSpotlight Artist: Alison Petty 3529Visual ArtBrandi Katherine Herrera37Elliot D’Antin 39Kate Hall 40Contributor’s Notes 41

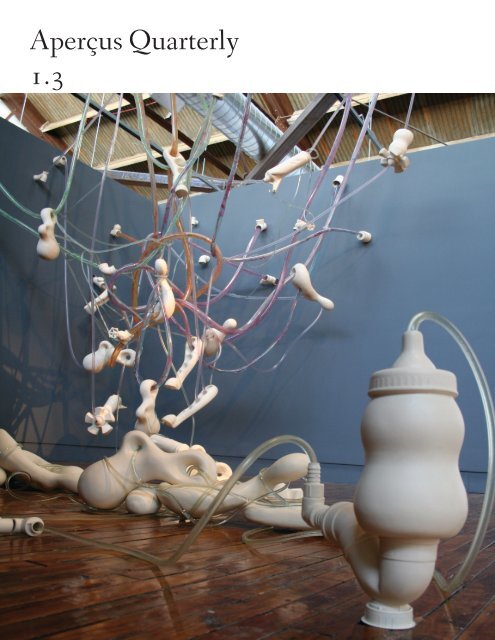

Alison Petty

Melodie BoltThe Science Fiction of Blues within Blue Eyeswith a nod to Frank HerbertAges after the accident he worm-thinks, worm-dreams,folds paper bits with ink squiggles to thump for rain.When it rains, he gets outside,wheels in the wheelchair to the driveto watch worms wriggle from earth to race in soggy gravel.Earth worms, Night Crawlers—great bait, I remember.Inside, he checks the cat’s ass for tape worms,wishes the dog had whip worms.He’s broken hearted for heart worms.He reads his scrapbook’s newspaper cuttings like a bookwormand he talks endlessly of sand worms—Little Makers and Shai Hulud.He sips coffee, stirring in cinnamon and sugar dunes.He wants cinnamon on toast, oatmeal, hotdogs, tacosbecause it’s spice. Not a spice, but the Spice. Melange.He swears his brown eyes will blue and he’ll travel without moving,folding space with his spice-heavy brain.But he doesn’t listen when I say,there are no triathlon races on Arrakis.6

Jerry Springer’s AudienceI watch that man cradle his head,hide his face when faced with her cheating.He believes all is lost.Springer’s crowd thrives on these moments of collapse,a man stripped of what he built, his woman gone cheating,his son declared not his own.The stranger the triangles the betterrelationshipsplices between cousins, man-stealing sisters,a father’s fling with a daughter-in-law.The crowd clamors for hair by the fistful,the flash of panty or boob,but are audience cravings ever met?Don’t their souls demandthe long shadows thrown by the Colosseum’s harsh sun?The Retiarius trident sunk deepin the tender flesh of Mermillo’s chest,nipple ripped, lungs punctured,helmet flung askew.The warm sand cradled his cooling body. Thenthe mob roared with venerationfor everything lost in an afternoon’s show.7

Boyd BensonTo Say the Wind is Another ThingTonight, the wind pushes through the treesbecause a door is open, and down the street children turna thousand laughs or cries into a sort of steady moanor song. The wind stumblesbecause clouds are gray and somewherein the Pacific another wind has paused.Because the sky is also far off.The wind blows because philosophy cannot move a tree.Tonight, the sky remains wide and unfathomable, except to wind —which, like any pale bureaucrat, can a lonesome thing befor so long and steady one might rarely notice.The wind blows because things happen above a city.Because a fable unwinds itself from an old man’s mouth.The wind blows because his hands tremble.Because he is my father or someone like my father.Because the sea turns blue after grayand before.8

Abby MurraySoldier’s Wife Writes Poemand all county residents are tuned into see how it was done, how she wasstanding in her driveway alone at dawnthis morning when she parted the ragsof hair flapping across her face and her eyeswere dry as stones, how she turnedcalmly toward the front door of her houseas if she were walking through the openingof a giant snail’s shell, into the kitchen,the hallway, the spare room used as an office;then between two stacks of bills, one paidone unpaid, she armed her pen, a clickheard round the neighborhood, the catsin the den pricked their ears in their sleep,two black dogs in the backyard stoppedlapping water from their silver bowl to hearthe sound of writing, the news crewthree miles out shouted an approximate addressand hopped in their vans with their satellitesand microphones and laptops and GPSwhile the woman at the center of it all,hair tied back by then in a knot over her neck,legs crossed at the ankles as she satin the eye of this rare storm swirlingtight circles around the crown of her head,lowered her instrument and the paperbeneath her fist was white as winterbefore she drew on top of it several words9

I Am Myself But No One KnowsI am myself but no one knowsbecause I wear a mustache,bushy like a sheriff’s mustache.My parents have me overfor dinner and say some okay stuffabout me but mostly admitI’m not that great, hardlya doctor, they would’ve lovedto have a doctor in the family,even though I’ve shown upwith a bottle of wine fromthe twenties, a perfect year, French.I’m rich. They say, “You remind usof our daughter but yourmustache is quite different.”I pour the wine in the kitchenand my mother clasps little charmsaround each glass stem,pewter fruit-shaped beads.I don’t gag but I cough a little.I ask my father about industry.He says he has a daughterwho’s never once asked himabout industry. I make a tsk noisewith my teeth to tell himthat’s very disappointingthen smile into my grey tweed lap.We have dinner, red beet lasagnawith bagged salad and rolls.Then coffee, lemon squares,paper napkins, more wineand I can’t get the charmoff my glass so I close my eyeswhenever I tilt it up to drink.Just before I leave, standingat the door, I take off my mustacheand hold it up like a prize trout,a trick! My father’s eyes get big,my mother slides her arm aroundhis waist and his eyes go back to normaland he giggles, “You really arevery much like our daughter,”his laughter shivers in his throatdisappearing like a stone tossedinto a pond, thwoop, nothing.10

I Am Not Lucky: A SestinaI will wake up having shed my bodyand transformed into the shape of a raccoon.My husband will give me a chance. He’ll trybringing me to the doctor’s office, calling mymother. We’ll separate quietly. I’ll insistimmediately upon custody of the trashin spite of myself, no lover of trashbefore my sudden change in body.Just think of what we throw away, I’ll insist,and my husband will look into my raccooneyes, just once, searching, waiting for myold self to reappear, to magically trysurfacing like a lily in the muck. It won’t. I’ll tryhis patience for changing shape, for loving trash.He’ll disappear, communicate only through mylawyer from that day on. I’ll curse my bodyall over again, this time alone, a raccoonwith an armful of trash and no one to insiston her behalf that change is best, insistI am worth my own breath. The lawyer will tryto politely ignore my raccoonways, answering the phone with trashin my mouth, just tasting it, the bodyof my conversation absorbed by thoughts on myhusband’s old t-shirts, which will then be mynew bed. The lawyer will listen, then insistI see a therapist. She can’t keep calling when the bodyof her legal work is done. Why don’t I tryyoga? The lawyer says it works. I’ll say trashworks, like chocolate-covered music to a raccoon.She’ll wish me luck, knowing I am not lucky. Raccoonswill start calling after that, skipping bottle caps off mywindow at night, promising me the freshest trashif I climb down from my apartment. They’ll insistthey are gentlemen. I’ll know better but let them tryto tempt me anyway. I will never forgive my body.My raccoon routine will get easier, loving trashwill come more naturally than loving my old bodyever did. I’ll insist no woman tried harder than me.11

Jan BottiglieriCastle Metals(a cebu)Once in the offices of the steel warehouse I wasthe manager’s small daughter visiting in a Sunday dress.In the wood-paneled room, there were papers on the deskand lovely organizational charts, fish bone diagramswith words clinging to them as their meat.My brother passes by, clever namesake,shaking hands in all his little-man-ness.He beams like two boys. My brother istwo boys riding by on the mail cart, laughing.My feet run themselves acrossthe checkerboard linoleum: blue-fleckedwhite, white-flecked blue, a sky with cloudsarrayed for optimum efficiency. No one knowshow little time my father has.Now a grey-suited man bends at the waist before me,lowers his red face like a sunset, takes my handinto his, white bird in a nest of rocks: we all loveyour father here—even the men in the back,the warehouse men, love him.The warehouse is last: my father keepsa hand on my brother, a hand on me, and from the wide windowwe survey the mountains and plains of stacked steel,the beams and rolls, the men in their orange hardhats.A few raise their hands to wave. Here and there,in brilliant fealty, the thrilling cutters spraytheir blue, obedient fire.12

AlphabetA is for anger, its iodine smear.B is better than that.C is coughing from the wings.D is a mild disturbance, butE shuts everyone up with its shrieking.F is fine, thank you,G no really, I’m fine.H has heavy hemisphere halves:I see them tipping their icy caps.J-K-L and hide. That’s my joke.M makes mountains with ferocious peaks,N nestles down between them.O if only I could too, oblique to thePage, Quiet, Resting on theSlopes with the sheep and goats.T is for tenor – no, bariTone.U pities V for its graceless point.WaX runs ruby off the table edge:Y? You tell me. Maybe gravity.Z is the arrow you can’t quite see.13

Dear Mr. Spock:My blue shirt, my backyard protector:so long since you last beamed down,we’ve lost our farthest planet, groundedour shuttles. It was Stardate 1969,Patton Street, Earth:Your mission, to learn all I knewabout everything – trees, curbs,cars, swingsets – a logical desire,the wisdom of my six years, complete.How patiently you’d listenas I catalogued my life!Barely green, the peaksof your ears; your black browrising, your alien interest.You were quick with the phaserif we got into a jam, but I knewyou wrote that book on babies,so must be kind. I’d tug your handinto mine and explain, explainuntil the light of our hydrogen sunfaded and you’d leave me behind(certain my parents would miss meif I beamed into space.) Dear Spock,some days I still find myselftelling you everything: This is the waywe pay bills, here’s a pen. Here arephotos, a phone, pay attention. I knowhow to make oatmeal, hospital corners.Here’s how it works. Again andagain: I know how this works.14

Kara ArguelloTop Thrill DragsterYou have dangled bare legs,gripped lap bars on steel and wooden giantsin three states.But today,on this thickly August afternoon, you are waitingin line for the world’s newest, fastest coaster.Four hours of faith through shutdowns and repairs,maddened by that song, baby I’m ready to go-oh!Then at dusk you slide into the very front car.Press your hip to his, breathe deepat the sound of the bell,let the ride thrust you up, impossibly up the vertical U.You don’t know this is the last ride—in 42 seconds you’ll descend,wind-blindscreaming lifeinto the platform,his hand will grip yoursas you sea-leg away,gaspingspitting bugs from your teeth,survival-high—that in months he’ll lose his mother,that in years you’ll flee the East,marry another.Right now there is only you two, hot on the edgeof a painted capsule, off the seat like some space jockeythundering around Saturn,over a pale silent moonscape, its lake a deep plum,whose shadow trees feel no sway as you racetoward love and death and then past.15

Robert PeakeBritish MatchesOn the matchbox, there is a child,frown like a downturned slice of melonflames decorating her thin stick arms.A single red wing arcs in saluteby the epigram: “Fire Kills Children.”Above it is the royal coat of arms.I wonder why only children. Fire killstrees, and adults, too—anything alive,once enfolded in that wing will soonhear the “shhh” of death’s librarian.My father taught me games with matches.We used to make rockets by wrappingthe match head in foil, propping iton a bent paperclip, then ticklingthe shiny underside with a flame.It would fizz into the air, danglingsmoke like a dancer’s scarf. I wentthrough whole booklets that way.Now we are six thousand miles apart,and the pale light of an unfamiliarplace lights up this new-to-me warning.In the absence of photojournalism,the idea of a child on fireis as cartoonish as a queenwhose family symbols are nationalsymbols, propped up by a unicornin a place that will never be home.16

Juan DelgadoFor AnnaThe hum of wings,a hummingbird’s hungerpuffing up the air—she feeds, a tiny storm,a redness, then hot lead,a side-way rocketpast the world’s ear.Like the wind’s sheep,dandelions flock ,following each other upward,a funnel of white,gauze-like curtainsdraping the sky.A Mountain Chickadeetoo full of seed chatterbounces on a twig;this ruckus amongthe cedar shade is a danceto waste time away.17

Standing WaterOn our way a crow in the sprinklersoakedivy sinks deeper until we canhear it squawk only when we pass,the ivy’s leaves trembling in sunlight.Later, we notice a set of wingsflattened by the side of the road;the wings, headless, large and gluedby their dried blood to the asphalt.We hurry the kids along when they ask“What’s wrong?” We hurry them pastthe fallen birds and the appearing oneshiding behind our Mexican flower pots.We begin to study the pools of water,the still water, the untreated water, turning greenin our sleep, breeding what we come to see:a hand nudging us beyond the unusual;a pair of eyes perched on our sagging clothesline;a beak singing into its own ruffled chest.18

Lisa CoffmanNot Choosing OtherwiseHere they say going to the snow. There we lay under itas it came on. Without the trouble of choosing otherwise.Let the heat of the rooms grow even oppressiveheld within the generous, empty touch of colduntil we could bear a little of our own coolness,stand naked in a room inside the snowing.It limited our waywardness, as it did the tarry slide of rivers.Muted the shapes of hills but retained them,working as memory does, blessedly covering.All day the slowness of it. The balked light.A presence that would not spend itself in one impulse.Or tears of the Virgin sent to anoint usthat cherished themselves on the way down and retainedremoteness even at the moment of blessing.In my room under the roof, by the sleeping dog,at my desk with a bird’s nest brought in from summer,and two horse bones that had worked their whitenessout of the earth of the bodyand then the earth where the body lay buried,I typed small neat dark tracks on paper,all of it open and slowly filling with snow.19

Light Comes At Me SidewaysI never live with balanceI always wake up nervousLight comes at me sidewaysI hold my breath forever–Bruce Cockburn, “Open”Tuesday sun laid on, I write, but it’s Thursdayand oh God the puppy’s dug up the yard.When I called the banjo holy, I meantwalks beside all things–creek in sun, walnutshitting a tin roof–it’s light’s hold on water,it’s the way the apostrophe holds the snot too close, a good dancing partner.Or that the fallopians don’t first touch the egg,but fringe it over, they could be adder heads,a Venus Fly Trap, I hope not, but anyway,isn’t all that swaying in the name of embrace?Sometimes I stray so and tangle in metaphorI end up making love to the wrong thing,B over the A, my own pleasure in manufacture.And why I like tangent better than pilgrimage:no posted lookout, no time to arrive,the best place to taste the lover’s mouth.For whenever did desire strut down the avenuesin full dress like a marching band drum major?Ah, the coyness of those summer screen doors–air stirred through, a figure darkening close–greatly open without seeming so.20

The Past TensePast tense, you bring near, you set next to mewhat is not.Such as This morning, I got up, fried eggs, walked the dog.I like your light stride across a sentence.I like the shadow you throw: first phase of an eclipsein which objects grow not darker but richer.Sometimes, when I am quiet, alone in my house,I hear you come into the the thing I’m doing.Where Akhmatova writes “On the copper shoulder of the Lyre playera scarlet bird sits,” you are secretly there.It is to you I turn for the kiss in the gardenand not the one who kissed me then.In you, in the last days, her appetite came back.She called for pork chops, a plate of greens,It is with you I bind all my possessionsto carry the way of all possessions.said, “When I was a girlwe never had a care,we kept the babies all morning in the morning airin white carriages.Grandfathers on the stoops rocked them.”21

Poem As Insect, Poem As BirdMichael writes, in the persona of Big Cup, in an introduction to his own book, “poemswork that thin line where words are mistaken for things.” I then glimpse poems asinsects, congregated at a crack of sap, working all the wound-lipped edges of the world.Mouthed up to skin, dung, a plate not claimed. Little crawling engines, black blood lineof marchers, so numerous that the carrying and coming back is a single shape, mobile asa mouth. Drawn to whatever spilled, parted, tore, petalled. The flower at its narrowest.The festered place for laying eggs. Out of this greed, this urge, a service.But today I see them as birds “watering sunlight with their air of shadow.” The smallbody I fasten the poem to, that it fashions for itself–our joint effort. The airy strength forthe exceeding migration. The way they throw themselves into flight. But hold the body amoment–downy & sharp ended, a hot scramble of claw and frightened heart, all theprecious shadings. The strange backward angle of the legs. They look precarious,breakable, but are crouched, gathering to leap. I hold it up or open my hand, I get out ofits way and may, for the ceremony, even say “go” but this was already set in motion–itsimply returns to the arc of flight interrupted: body making flight making body22

LisaCoffman“The subject of a poem is as foreign to it and as important, as his name is to a man”–Paul Valéry.My two namesshow up for a while around people I don’t know.Out on the periphery, they stay trained on melike binoculars or a loyal dog.Called out, they grant me passage,perhaps with a smattering of applause,to the front of an auditorium’s shiny fidgets and coughs,or to the head of a third-grade class, to read my poem on a squirrel.Weeks go by and I may not hear them both.They are like a skirt and shirt I wouldn’t wear togetherthat turn up side by side on a clothesline to dry.Without my two names I cannot owe money,give an answer at a borderor lie under a grave stone.I suppose I have come to blame them for this sort of thing.We share a flawed loyalty: they remainindifferent to any change on my part, any redemption.They intend to outlast me, while Iwill betray them at once for my darling or mama.We have gone on so long like thisin the dentist’s waiting room, on the job applicationthe book jacket, the church Christmas play program.Today my friend brought a poem about an orange,such a poem! its mist and rind hung in the air after we shared it.I heard him say, as he left, “Lisa Coffman, sail on”though now he claims he said “Lisa see-saw” and staggered off howling.The point is this: I turned to my names with such hope.I think I am still listening for my mother’s voice.I think I turn out of that portion of love which is obedienceand therefore never sure if it is love.I turn quickly because now I protect her,I turn toward her the part of me my names never covered.23

Alison Petty24

Andrew StarkOliveMy friend Jessie killed himself on a Monday in springtime. Turns out, most people kill themselves onMondays in springtime. It doesn’t make sense, spring being a time of new life. But the depressive wakes to birdsongand sunshine, to flurries of pollen, and it all seems like a broken promise, the illusion of happiness. That’show Jessie put it, anyway. We were installing a new phone system at the Tribal Center, both of us shoehornedin the attic rafters, saturated with sweat while running network wire, and he just started crying. I thought he waschoking on those pink pillows of insulation, all the glass-reinforced grains between our teeth like dust.“Jesus,” he said. “Jesus Christ.”It was as if he’d just relayed to me some doctor’s damning pronouncement that rapidly upped his expirationdate, a giant cancer, perhaps, like an octopus hugging his brain, threading its awful tendrils around his spine,working toward his heart.He was the type of guy you’d forget you ever went to school with – he blended into the lockers, meldedwith the Formica, and in class pictures, second row back, third from the left, the blacks and reds of his ChicagoBulls t-shirt integrated seamlessly into the backdrop of encyclopedias and flashcards. He never raised his hand,and (in my memory, anyway) he seemed like an organic extension of the desk itself. He might as well have neverexisted at all. And Jessie – my remarkably unremarkable friend – slipped into a routine, rappelled into the channelsof habit as if off a cliff. Every night he’d close George’s Tavern, climb behind the wheel of his rusted-outChevy S-10 with a couple liters of vodka sloshing around in his gut, and drive up to the Holiday station wherehe’d buy a six-pack of Coors and a microwavable bean-and-cheese burrito before heading home to his dingy onebedroomon Baraga’s shoreline and drinking himself further into the undertow. His name had never appeared inthe newspaper; he was rarely, if ever, the topic of anyone’s conversation.He had the occasional girl, sure, called them “Rez Dogs.” But tangling with girls here is a gamble. Sayyou sleep with some pretty cocktail waitress at the casino, or you flirt with a sexy bartender at the Sidetrack, oryou score the phone number off a nurse at Tribal Health. Any given hour in the nights following, you might windup with her hammered ex-boyfriend stumbling up to your house with a bat or a shotgun.I’ve had the occasional girl, too, but it’s been a while. In the same way captive old pups in a pound acclimateto the cold cement floors, the concrete vistas and the steel horizon, I’ve learned to accept loneliness. Thegood girls flee or head off to college and marry Business majors or Economics buffs, guys who fold their sweatersand wash their hands after they take a piss. Or they’re ruined early, at around twelve years old, by drugs or pregnancy.Or they die, like Ginny did. She worked as a cashier at the Pines Convenience Center. And she really wasbeautiful – pale as the belly of a lake trout, with inkblot eyes and thick black hair. I liked Ginny. After work, I’dwaltz in there and buy a six-pack or a pint, and she’d get all squirmy and smiley behind the counter. We’d bitchabout our jobs or just chitchat about whatever, but the place was always busy with folks blowing their welfarechecks on booze or cartons of Seneca 100s, so our conversations were brief. Then, one night last July, her boyfriendhad a meltdown and sawed her head off with a buck knife. Thankfully, people said, her two kids were stayingwith their grandma at the time.25

I never left Baraga, stuck around to navigate the murk like a bummed mariner. I’m a phone man. It’s a paycheck.This town’s got one of the highest unemployment rates in the nation, so I should feel lucky. But when I’mjackknifed in somebody’s grimy crawlspace, tinkering with forty-year-old telephone wire and sweating throughthe band of my faulty headlamp, I don’t feel lucky, or whenever I limp into my house after spending all day troubleshootingin some sweltering attic, cocooned in fiberglass insulation. I’ve worked in just about every building inthe county, running wire through the foulest bedrooms and crawlspaces imaginable. I pulled cat-5 cable the lengthof the Ojibwa Casino’s subbasement, shimmying my way through a froth of foot-deep sump leakage. I crashedthrough the suspended ceiling of Winkler’s Nursing Home while installing a new voicemail system and shatteredmy femur. I’ve been chased down the street by a Saint Bernard, had my calf mangled by a surly beagle, and, aftertussling with a German Shepherd, I almost lost a finger. One time, the power went out while I was stapling wireto the rafters in the basement of a downtown tenement building, and I tripped over a dead cat. Ten years ago, mysenior class voted me “Most Likely to Succeed.” I guess I have.***On March 21st, the official first day of spring, we’re hit with one hell of a storm – freezing rain, high windsand downed tree limbs. The sky is a heavy gray lid, and slush keeps reefing my truck from one side of US-41 tothe other as I drive toward Calumet to check the hum on a line at a Lutheran church. I figure the weather will onlyget shittier up north, so I decide to turn around and can the rest of the day. I go to the Pines and buy a fifth of JackDaniels. I’m standing in line, eyeing the enormous middle-aged checkout woman resting her bulk on two aluminumforearm crutches, and I’m struck with a cold pang that sighs through the atriums of my heart. I seem to beslipping down through the dark strata of routine myself these days. I drink too much, but so does everybody else.I’ve quit working out, too, which used to be my thing. Humping weights around at the gym broke up my day, andrunning myself sick on the treadmill took my mind off things. Life is supposed to work like a sinusoidal wave,full of ups and downs, but recently mine feels like an ellipsis, like I’m idling.After Jessie died, I studied up on suicide. I wanted to understand it or to acquire a frame of reference fordespair of that gravity. I read the statistics, but they meant nothing to me. I perused newsgroups on the internet,browsing the forlorn, oddly matter-of-fact exchanges between depressives and the terminally ill as they formedsuicide pacts before my eyes. Many agreed on pills, like the veterinary anesthetic Nembutal, or stringing a nooseover their bedroom door and letting gravity do the work. Most people shot themselves, and a lot of Europeancontributors hopped in front of a train. But there was one common denominator: they were finished.I keep a Glock 9mm in my underwear drawer. Sometimes I take it out, load all seventeen rounds into themagazine, and feel every ounce of the gun’s blued finish in my hand. Or I fieldstrip it, laying the pieces out onmy kitchen table like a dissected predator. Three weeks ago, I’d had quite a few drinks and I pressed the muzzleagainst my head. The gun wasn’t loaded. I just wanted to know what it felt like.The storm is clearing by the time I pull into my driveway, the whiskey tucked under my arm as if I intendon running it down a football field. I step out of the truck, lose my footing on some black ice and go down. Thewhiskey – thank God – survives the fall, and it’s jutting neck-up out of a small snow bank. I scramble to my feetwith a grunt and retrieve the bottle like I’m lifting it from an ice bucket. Then I notice a small fuzzy caterpillarupon an oblong island of gravel beside my left boot. The thing looks like a black and yellow pipe cleaner, curledup into a sort of defensive position against the cold. I return the whiskey to its ice bucket, as it were, and, gentlypinching the caterpillar between my thumb and forefinger and then cupping it in my hands, I lift the insect to myface. It isn’t moving, so I breathe onto it. I walk into the house, breathing away, and leave the whiskey where itsits.26

I’m standing in my kitchen, huffing and puffing, giving the bug mouth to spinneret, really, and it finallyunfolds. I run the tip of my finger along the length of it, brushing its bristly setae. It rears up exultantly, and Ialmost lose it right there, almost dissolve to tears in my kitchen like a widower might after recovering some forgottenmemento from a junk drawer. I rifle my cupboards for a Tupperware container, and then dutifully line thebottom of it with romaine lettuce. I tear an S.O.S. scrubbing sponge in half, saturate it with tap water, and arrangeit in the corner of the caterpillar’s new digs like a piece of oddball furniture. I name her – I decide it’s a she – Olivebecause it’s the first word that comes to me. Olive probes around, hiking the verdant topography of the lettuce,testing the wet sponge, and she looks happy.This is different. This breaks routine. And routine is a tough thing to break in a Reservation town oftwelve-hundred. Twelve-hundred – more a body count than a populace. Our factory workers and high school kidsare as fluent in medical jargon as any EMT virtuoso, and their doublewide homes are like goddamn pharmacies.Down at Larry’s Market and Wilkinson’s Hardware, there’s always a run on Sudafed and TheraFlu for their pseudoephedrine,always a run on lye, distilled water, hydrochloride, battery acid, lantern fuel, and whatever else goesinto a methamphetamine stew. But prescription drugs are all the rage, and our doctors are family-practice pushersthemselves, doling out scripts as perfunctorily as Blackjack dealers divvy hands in the casino. That’s what Jessienever understood – and he was one of the good ones – that the quicksand of routine is everywhere, waiting foryou to misstep. But the most effective way to escape quicksand is to have somebody around to help you out.But for Jessie it was too late. Decisions had been made, plans had been finalized. His trip was booked.And that night, after we finished running network wire in the attic of the Tribal Center, Jessie didn’t go to the bar.He didn’t sink a quarter-gallon of vodka, didn’t show at the Holiday station for a six-pack and a burrito. He drovestraight home, sat down on the linoleum in the corner of his kitchen, and surrounded himself with saved birthdayand Christmas cards sent from his dad out in Wyoming. Then he propped his rifle under his chin, and I’d like tothink he prayed. I’d like to think he made some final arrangements, you know, reserved a spot or something. BecauseJessie was one of the good ones.I’m crying now. And I love this damn caterpillar. I’m beaming into her den, and I’m wearing the busted,spent smile of a new mother cradling her new child. This is different. This breaks routine.27

Alison Petty28

Paying Attention To It AllWithLisa CoffmanThe following interview was conducted by <strong>Aperçus</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> editors, Lauren Henley and JonathanMaule, from October 7th to November 22nd, 2011.LH: Do you remember the first time you were exposed to poetry that moved you?LC: It precedes memory. I know the date, though–Christmas 1965–because it’s written in the front of my copyof The Big Golden Book of Poetry, a Christmas present from some cousins that Christmas. I would have been alittle over two years old. My mother, who says she wasn’t read to at all as a child (one of her parents chronicallyvery ill, the other working to get out from under the hospital bills), read these poems to me. From them I got theidea that poetry is some kind of magic incantation, inseparable from music, just fun to take in your mouth andlet spill back out. A lot of those poems and their illustrations stamped themselves into me, like the glee of therefrain in this, “The Baby Goes to Boston”:What does the train say?Jiggle joggle jiggle joggle!What does the train say?Jiggle joggle jee!Will the little baby goRiding with the locomo?Loky moky poky stokySmoky choky chee!Apparently, at age two I could recite fairly long poems like “Custard the Dragon” after hearing them a fewtimes. I’ve never had a particularly good memory, but I can and could take in and hold poems. I think they justmade me feel good, even then. What I still love in poems is very tied up in how the line feels–is it solid enough,musical enough, that I can pick it up and carry it around? Like a musical two-by-four, like something solid andpretty enough to build with.I didn’t read a great deal of poetry in high school. In my early college years, I loved Hardy and Tennyson–wasdrawn to the drama of their work. I memorized Tennyson’s “Ulysses” walking to work the summer after myfreshman year, and Hardy’s “During Wind and Rain.” I love “down their carved names the rain-drop ploughs.”The first contemporary poetry that hooked me–the first contemporary poetry I read–was during my senior yearof college, when I was finishing a major in computer science, and took a poetry writing workshop: poems byGalway Kinnell, Sharon Olds, Louise Glück, William Carlos Williams. Also Appalachian writers including JimWayne Miller and George Ella Lyon. These were early influences.29

LH: In a review of Likely posted at ForPoetry.com, writer and editor Brad Bostian states that James Wright “isan obvious influence” for you. Would you agree with this?LC: Wright is an influence; I certainly love many of his poems. I don’t know that he’s more obvious than theothers I listed above. Yehuda Amichai (who also was my teacher at NYU) remains a major guiding light. RobertFrost was a big influence when I was writing Likely; so were Linda Gregg, Charles Wright, Elizabeth Bishop,Robert Lowell, Wallace Stevens, Mary Oliver, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound. These were some of the first poets Iread deeply and carefully and with awe—I looked to them to see how it was done.Another major influence on my work is the physical place I live in. The landscape, its weather and seasons andanimals. The streets and canals, the paved-over and razor-wired places. In some way, I think I’m always comparingwhatever place I’m in to East Tennessee, where I grew up.JM: Speaking of being influenced by physical place, you lived in a cabin on Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateaufor six months. What events led up to this experience? Can you give us a visual of the Cumberland Plateau andyour humble abode?LC: The first six months of 1995, I lived in a board-and-batten cabin on a hill above the Clear Fork River inRugby, Tennessee, on the Plateau. I used part of a poetry fellowship I’d received from the Pew CharitableTrusts to stay there.Rugby was an attempt at a utopian community founded by British author Thomas Hughes in the 1880’s, fundedin part by proceeds from his book Tom Brown’s School Days. The community flourished and then waned by theearly 1900’s, leaving behind a small town of crisply detailed Victorian houses on the wild Appalachian Plateau.It’s a fairly secluded tourist town now (the seclusion making the tourist trade challenging), but still has thatutopian community vibe—lots of music, traditional crafts, artists coming through, mixed with history buffs andpeople who love that part of the Plateau.I went there because it was near the defunct mining town where my mother had been born–Glenmary, Tennessee.I wanted to find out more about my mother’s side of the family and live in a place that had given rise to somany family stories: the great-great-great grandmother who ran a farm and never married; the great-great grandfatherwho slipped through Confederate lines to fight for the Union; the boom times when the coal mine was going,the passenger railroad came through, and my great-grandmother owned a hotel. Also I simply wanted to beon the Plateau, which is geographically a very rugged part of Appalachia, even by Appalachian standards. Andbeautiful: rivers, craggy bluffs, thickly wooded hills.JM: How has moving to California’s central coast affected your poetry?LC: I’ve lived here ten years now, moving with my husband, a native Californian, to the central coast the yearbefore our daughter was born. At first I was in shock: no seasons (at least, as I understood seasons). No rain,except during a fairly narrow slice of the year. Few of the trees I knew. These were the rhythms I’d lived withall my life and I grieved their loss deeply. I suppose I still do.For a while, I shut down in my writing because of that shock. Probably the move turned my poems more inward.I don’t make things up so much as report what’s around and in me, and I didn’t yet have a connection towhat was around me.30

But of course those connections grew. The ocean, the oaks, the stone-faced mountains. People I’ve come toknow intimately here. That’s the soil my poems grow from. Also, I think my work with Buddhist teachers atSpirit Rock Meditation Center in Marin County has shaped my writing: what I’m willing to see, what I’m willingto sit with. Although, obviously, Buddhism has its roots in India and China, this seems to me an influence Ihad to reach California to get. California’s been good to me.LH: In a telephone conversation we had, you mentioned that you were a dancer for many years. What forms ofdance did you study? How does the physicality of dance interconnect with the movement of language in poetry?I think of your poem, “About the Pelvis”…Pelvis, that furnace, is a self-fueler:shoveler of energy into the body.It is the chair that walks. Swingthat can fire off like a rocket.LC: I studied classical ballet from age 7 through my early 20’s, discovered modern dance in my late 20’s (thatexperience inspired the pelvis poem, which I used to subtitle “Or, Introduction to Modern Dance”).I think dance has influenced my idea of the body of the poem. But how? Maybe that it should be strong, be ableto do the heavy lifting and big leaps, but not show strain of the effort required for such things. Also that thepoem should have a rhythm to move to, walk to, hold on to, be pleasured by—not a strict meter but somethingphysical as well as cerebral. Something that engages the body, like dance does.JM: Your poems seem to deal with introspection and entropy—how the emotive inside perceives the destructiveoutside. How do you find balance when writing about dire situations and oppressed people?LC: I don’t think I find balance. I think I write from an unbalanced place, and try to describe the pitch of theslope I—and others—are tumbling down. If I try to fix things, or comfort myself (as I am often tempted to do)then I don’t think I do as good a job with the material.And usually, it feels the destructive is right in there with the emotive, that there’s as harsh a destruction going oninside as out. That’s the dangerous labyrinth to the isolation that my writing seems to need. I’ve never learnedto balance the aloneness writing requires from me with the being out in the world that writing requires from me.Oddly, though, writing about imbalance provides a kind of balance. To write “I am tumbling down a steeplypitched slope” both documents and, somehow, provides a counter motion to the fall.LH: Do you enjoy writing fiction or non-fiction as well?LC: I’m drawn to nonfiction; I love the essay space to explore things. I’m also sort of hooked on feature-lengthjournalism. In 1989, I worked for the North Jersey Herald and News, a daily newspaper in Passaic, New Jersey,and wrote feature stories for their Sunday Lifestyles section (a very neglected section, I might add, since everyonein the area read the New York Times on Sunday). Later, for much of 1991-1997, I worked as a freelancewriter, and some of my favorite work was doing feature stories. I covered everything from professional baseballand local breweries to interior decorating (which I knew almost nothing about). I don’t necessarily enjoythe deadline writing, the having to get out and interview people and press them for information and comments,but it’s good for me, and I absolutely love the feeling when I file the story. Essays accommodate that kind ofresearch, but also allow for more introspection, more quirkiness–I suppose they’re a kind of poem/feature story31

lend to me. Last year, I won a nonfiction competition sponsored by ARTS Obispo for an essay about a 1933murder on the Plateau. I’m working this into a longer book-length piece. Moving between poetry and prose isa good mix for me, when I can set up my schedule to allow it.JM: I feel like Tennessee is lucky to have you as one of its poets. What advice do you have for other writersliving in depressed environments? How can they benefit from living in an economically or spiritually deprivedlocale?LC: More like, I’m lucky to have Tennessee. There are writers on the ground there—Jeff Hardin, Bill Brown,Linda Marion come to mind because I’ve just been reading them, but there are many others—who are doingbeautiful work rendering the day-to-day, the landscape, the habits and rhythms. Diane Gilliam’s Kettle Bottomon the West Virginia 1921 mining wars is some of the best poetry I’ve read. These writers are my guides.My advice to writers in deprived locales doesn’t differ from advice I’d give to any writer. But perhaps in thoseareas it’s more difficult to practice: pay attention, a lover’s searching attention, to it all. Try to say its name.32

Alison Petty33

Alison Petty

Spotlight Artist:Alison PettyThe following interview was conducted via email by <strong>Aperçus</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> editors, Lauren Henley and JonathanMaule, between October 25th and November 23rd, 2011.LH: Seeing your work, especially Cross Section Series and Specimens, I imagine a young Alison Petty avidlypeering through a microscope in biology lab. Am I way off? Were there any other fields of study that you werepulled towards? Any parents hoping you’d become a scientist?AP: No, I was never very good at science, in the conventional sense. I think I learned about science through art. Igrew up with a father who was a pediatric rheumatologist (specialized doctor) and he had some pretty cool bookswith great diagrams of joints and the human body in general. All the medical models in the doctor’s office alsointrigued me. I am sure this had some influence. I was lucky that my parents never tried to project much ontome—they really just wanted me to pursue my passion.LH: When did you realize the potential of rubber, clay, and porcelain?AP: I was first drawn to rubber byway of glass for its translucency, something that rarely happens in ceramics. Iwas in grad school and I really was interested in buffering porcelain’s fragile nature. I was thinking about it likebones and flesh, hard and soft, natural and synthetic.LH: You were a resident artist at the Taller Cultural in Santiago de Cuba as well as the Jingdehzen Pottery Workshopin China. This is a tall order, but can you summarize for us those experiences and how living and learningwith different people groups has inspired your work? I realize you can only give us a snippet of an undoubtedlyvery rich time of your life….35

AP: Well, I have traveled quite a bit in my life, so it felt natural to travel and make art in a location. Cuba is a reallymysterious and passionate place, and I really value the people I met and the lessons I learned. Cubans have solittle materially speaking, and yet they have so much joy and happiness! It really was remarkable. In China, it wasa different situation. Ceramicists just saw themselves as cogs in the industrial machine, and not as artists…quitesad really. But it was exciting to be around so much ceramic industry. I was more focused on producing work ina short amount of time. At both residencies, it was so great to focus, get work done, and meet fellow artists. Nowthat I have a family, I really miss those opportunities.JM: What advice do you have for young artists who are struggling to make a living and who may be consideringa career based on economic necessity?AP: I think that it is really important to be authentic and professional. Trust your instincts and always do the rightthing as an artist. Be willing to work hard and collaboratively, and not to let the ego get in the way. Never burnbridges because the art world is small.JM: Can you name a few artists that have inspired you? Were there any particular ceramicists who got you excitedabout ceramics at an early age?AP: Yes, I love Kiki Smith, Ken Price, Charles Long, Louis Bourgeoius, and Jeff Koons. I have also been highlyinfluenced by the Droog designers and Karim Rashid.JM: How has having a family influenced your work?AP: Well, it has forced me to be more patient…and not be so self obsessed! I am not really sure [how having afamily has influenced] the content of my work, as I was interested in reproduction way before I had a child. PerhapsI am less in awe of it now that I have done it.JM: Have you always wanted to teach ceramics? How has teaching influencedyour perspective as an artist?AP: From a pretty young age, I knew I wanted to be a ceramics professor. I really have no other training, andluckily it worked out for me. I do feel quite fortunate. There are few jobs and many excellent clay people.Teaching keeps me open minded. I generally love working with my students, and they often help me with mywork. It can be lonely making art, but I have been fortunate enough to have many student assistants work with meon large projects. From public art works, the cross section ellipse that spans 26 feet long, to curatorial projects.That is the best learning for my students. They get real live experience, and they love to see me in action—blundersand all!JM: What exciting things do you have planned for 2012?AP: I currently have a solo show up that runs through Jan 2012 at the International Museum of Surgical Science.I am also working on a second public art piece with my students that will involve 256 square feel of ceramic tilethat will be installed outside of the CSUSB campus sometime in 2012. Finally, I am having my second child inApril, so I am clearing my work schedule!36

Brandi Katherine HerreraSelf PortraitTory37

Luch[a]moreAmerican EthnicIthaca Winter38

Elliot D’AntinBright Gaze, by Elliot D’AntinAcrylic on Masonite39

Kate Hallplease don’t define me, by Kate Hall40

Kara Arguello was born and raised in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania and now lives, works and writesin San Jose, California. Her work has appeared in Allegheny Literary Journal and Snail MailReview.Boyd W. Benson has recently moved to Everett, WA. He has worked as a cook, a janitor, a deliverydriver, a bum, an instructor of English, and taken a stab at various other lives. In 2007,his twenty-poem manuscript “The Owl’s Ears” was included in Volume 1 of the LOST HORSEPRESS NEW POETS SERIES: NEW POETS SHORT BOOKS, edited by Marvin Bell. His poemshave appeared in The Iowa Review, Ascent, Free Lunch, and other publications and anthologies.Melodie Bolt lives and works in Flint, Michigan. She’s earned an M.A. in English Compositionand Rhetoric from University of Michigan-Flint, an MFA in Writing from Pacific University inPortland, Oregon, and is currently a candidate for the MAT TESOL from the University of SouthernCalifornia. Her poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in magazines like Verse Wisconsin,Yellow Medicine Review, Gutter Eloquence, WORK Literary Magazine! and Tales of the Unanticipated.Jan Bottiglieri lives and writes in Schaumburg, Illinois. Some of her previous publications includeRattle, Margie, Harpur Palate, Court Green, and the anthology Brute Neighbors. Jan is anassociate editor with the literary journal RHINO and a freelance writer, and the most recent thingshe baked was chocolate chip banana bread.Lisa Coffman draws her writing from landscapes and experiences that have shaped her—particularlythose from her native East Tennessee and from her current home on the Central Coast.She has received fellowships for her poetry from the National Endowment for the Arts, the PewCharitable Trusts, the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, and Bucknell University. Her firstbook of poetry, Likely, won the Stan and Tom Wick Poetry Prize from Kent State UniversityPress.Elliot D’Antin has loved to paint from the instant his brush touched the canvas. He is currentlyattending Cal Poly Pomona for a baccalaureate degree in general anthropology, and someday hewill attain his doctorates. In his spare time, he enjoys playing guitar recreationally, and for hisunnamed band.Juan Delgado’s collection of poetry, Green Web, received the Contemporary Poetry Series Awardand was published by the University of Georgia Press. El Campo was published by Capra Press,and A Rush of Hands is in its second printing with the University of Arizona Press.41

Katie Hall wants to take her mind and her heartPut them in separate glass boxesTake a braided string and connect the two, string tying the heart and mind togetherAnd put it on display for whoever would dare to indulge in the ways that braid spinsThey may look, touch, hell, even taste the braidShe’ll leave a comment question and concern box there, too.Brandi Katherine Herrera is a poet, freelance writer, and painter, living and creating in Portland,Oregon. Her feature stories, reviews, and author profiles have appeared in The Oregonian,The Jackson Free Press, BOOM Jackson, The Ithaca Times and Madison Magazine. Her poetryhas ppeared in Written River: A Journal of Eco-Poetics, and Charlotte: A Journal of Art and Literature.This is her first fine art publication.Abby E. Murray, a 2011 Pushcart Prize nominee, graduated with her MFA from Pacific Universityand currently teaches creative writing in Colorado Springs. Her poetry has been published inrecent issues of War Literature & the Arts, RHINO, Salt Hill, Confrontation, and Court Green.Her first chapbook, Me and Coyote, was selected for publication by Marvin Bell in the 2010 LostHorse Press New Poets / Short Books series.Robert Peake was born on the U.S.-Mexico border, studied poetry at U.C. Berkeley and PacificUniversity, and lived in California for the first thirty-three years of his life. He relocated to Londonwith his English wife in May 2011. He is a new member of The Highgate Poets, and is enjoyinggetting to know the UK poetry scene. He writes about it all at www.robertpeake.comWorking for over fifteen years, Alison Petty Ragguette has developed an innovative approachto making objects in porcelain, glass, and rubber. Alison received her B.F.A. in 1997 from ConcordiaUniversity, Montreal and her M.F.A. in 2004 from the College of Arts, San Francisco. Shecurrently serves as an Assistant Professor of Art in ceramics at California State University, SanBernardino. Alison’s work has been included in over fifty national and international exhibitions,including her most recent solo exhibitions at the Robert V. Fullerton Art Museum (San Bernardino)and Objct Gallery (Pomona). She has exhibited at venues including the Deborah Martin Gallery(Los Angeles), Galleria De Los Oficios (Santiago de Cuba), Shanghai University Art Gallery(China), and Harbor Front Center (Toronto). She is currently working on a solo show that opensthis summer at the International Museum of Surgical Science (Chicago).Alison has been a resident artist at the Taller Cultural in Santiago de Cuba, Jingdehzen PotteryWorkshop in China, and the Purosil Rubber Company in Corona, California. Her work has beenhighlighted in several art publications and textbooks, including a recent feature article in CeramicsMonthly written by Dr. Billie Sessions. Alison has been supported by grants from the CanadaCouncil for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, and the Durfee Foundation in Los Angeles.Alison maintains an active studio where she lives with her family in Claremont, Ca.42

Andrew Stark grew up on a small Indian reservation in Northern Michigan, where he still worksas a grunt for the local telephone company. He was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, but thenmoved north. After graduating from high school, he attended the School of the Art Institute ofChicago. Seeking a more concrete academic environment, as well as a student body with less facialtattoos, he transferred to Marquette University. Two years and a handful of fortuitous andalcohol-fueled misadventures later, Andrew was expelled. Later still, he was somehow acceptedto Carroll College in Helena, Montana, where he earned his degree and met his future wife, Emily.He recently earned his MFA in Creative Writing, but otherwise writes in his spare time. Helives in Northern Michigan with his wife and their two Chihuahuas, Jasmine and Gizmo.43