Alcyon Project: Protecting seabird and marine IBAs in West Africa

Posters from the Alcyon Project: Protecting seabird and marine IBAs in West Africa

Posters from the Alcyon Project: Protecting seabird and marine IBAs in West Africa

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

2 nd World Seabird Conference<br />

“Seabirds: Global Ocean Sent<strong>in</strong>els”<br />

26-30 October 2015 Cape Town, South <strong>Africa</strong><br />

FEEDING ECOLOGY OF THE CAPE VERDEAN SHEARWATER<br />

(Calonectris edwardsii) POPULATION OF RASO ISLET, CAPE VERDE (P1-B-11)!<br />

Isabel Rodrigues 1,3; Nuno Oliveira 2 Rui Freitas 3 Tommy Melo 1 Pedro Geraldes 2<br />

1<br />

Biosfera I, Cabo Verde, www.biosfera1.com; 2 SPEA, Portugal, www.spea.pt, 3 Universidade de Cabo Verde, www.unicv.edu.cv<br />

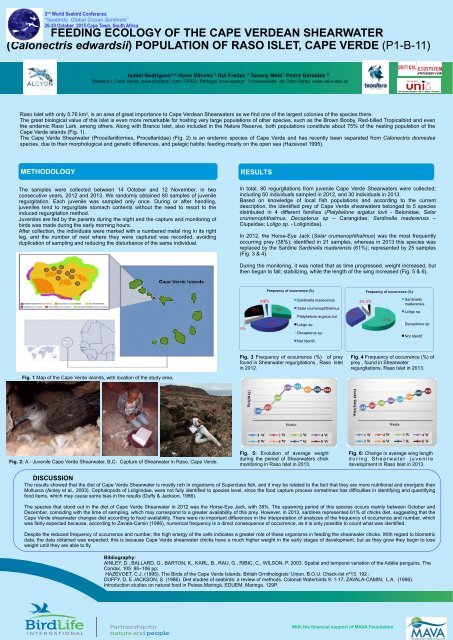

Raso Islet with only 5.76 km 2 , is an area of great importance to Cape Verdean Shearwaters as we f<strong>in</strong>d one of the largest colonies of the species there.<br />

The great biological value of this islet is even more remarkable for host<strong>in</strong>g very large populations of other species, such as the Brown Booby, Red-billed Tropicalbird <strong>and</strong> even<br />

the endemic Raso Lark, among others. Along with Branco Islet, also <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the Nature Reserve, both populations constitute about 75% of the nest<strong>in</strong>g population of the<br />

Cape Verde isl<strong>and</strong>s (Fig. 1).<br />

The Cape Verde Shearwater (Procellariiformes, Procellariidae) (Fig. 2) is an endemic species of Cape Verde <strong>and</strong> has recently been separated from Calonectris diomedea<br />

species, due to their morphological <strong>and</strong> genetic differences, <strong>and</strong> pelagic habits; feed<strong>in</strong>g mostly on the open sea (Hazevoet 1995).<br />

METHODOLOGY<br />

RESULTS<br />

The samples were collected between 14 October <strong>and</strong> 12 November, <strong>in</strong> two<br />

consecutive years, 2012 <strong>and</strong> 2013. We r<strong>and</strong>omly obta<strong>in</strong>ed 80 samples of juvenile<br />

regurgitation. Each juvenile was sampled only once. Dur<strong>in</strong>g or after h<strong>and</strong>l<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

juveniles tend to regurgitate stomach contents without the need to resort to the<br />

<strong>in</strong>duced regurgitation method.<br />

Juveniles are fed by the parents dur<strong>in</strong>g the night <strong>and</strong> the capture <strong>and</strong> monitor<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

birds was made dur<strong>in</strong>g the early morn<strong>in</strong>g hours.<br />

After collection, the <strong>in</strong>dividuals were marked with a numbered metal r<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> its right<br />

leg, <strong>and</strong> the number of nest where they were captured was recorded, avoid<strong>in</strong>g<br />

duplication of sampl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>g the disturbance of the same <strong>in</strong>dividual.<br />

In total, 80 regurgitations from juvenile Cape Verde Shearwaters were collected;<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g 50 <strong>in</strong>dividuals sampled <strong>in</strong> 2012, <strong>and</strong> 30 <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong> 2013.<br />

Based on knowledge of local fish populations <strong>and</strong> accord<strong>in</strong>g to the current<br />

description, the identified prey of Cape Verde shearwaters belonged to 5 species<br />

distributed <strong>in</strong> 4 different families (Platybelone argalus lovii - Belonidae, Selar<br />

crumenophthalmus, Decapterus sp – Carangidae; Sard<strong>in</strong>ella maderensis –<br />

Clupeidae; Loligo sp. - Lolig<strong>in</strong>idae).<br />

In 2012, the Horse-Eye Jack (Selar crumenophthalmus) was the most frequently<br />

occurr<strong>in</strong>g prey (38%); identified <strong>in</strong> 21 samples, whereas <strong>in</strong> 2013 this species was<br />

replaced by the Sard<strong>in</strong>e Sard<strong>in</strong>ella maderensis (61%); represented by 25 samples<br />

(Fig. 3 & 4).<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g the monitor<strong>in</strong>g, it was noted that as time progressed, weight <strong>in</strong>creased, but<br />

then began to fall; stabiliz<strong>in</strong>g, while the length of the w<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>creased (Fig. 5 & 6).<br />

CMYK - blue to green<br />

5%<br />

27%<br />

0%2%<br />

Frequency of occurrence (%)<br />

37%<br />

29%<br />

Sard<strong>in</strong>ella maderensis<br />

Selar crumenophthalmus<br />

Platybelone argalus lovi<br />

Loligo sp.<br />

Decapterus sp.<br />

Not Identif.<br />

Fig. 3 Frequency of occurrence (%) of prey<br />

found <strong>in</strong> Shearwater regurgitations , Raso Islet<br />

<strong>in</strong> 2012.<br />

32%<br />

5% 2%<br />

Frequency of occurrence (%)<br />

61%<br />

Sard<strong>in</strong>ella<br />

maderensis<br />

Loligo sp.<br />

Decapterus sp.<br />

Not Identif.<br />

Fig. 4 Frequency of occurrence (%) of<br />

prey , found <strong>in</strong> Shearwater<br />

regurgitations, Raso Islet <strong>in</strong> 2013.<br />

A<br />

Fig. 1 Map of the Cape Verde isl<strong>and</strong>s, with location of the study area,<br />

Raso Islet - Cape Verde<br />

B<br />

C<br />

Fig. 2: A - Juvenile Cape Verde Shearwater, B,C- Capture of Shearwater <strong>in</strong> Raso, Cape Verde.<br />

Fig. 5: Evolution of average weight<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g the period of Shearwaters chick<br />

monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Raso Islet <strong>in</strong> 2013.<br />

Fig. 6: Change <strong>in</strong> average w<strong>in</strong>g length<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g Shearwater juvenile<br />

development <strong>in</strong> Raso Islet <strong>in</strong> 2013.<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

The results showed that the diet of Cape Verde Shearwater is mostly rich <strong>in</strong> organisms of Superclass fish, <strong>and</strong> it may be related to the fact that they are more nutritional <strong>and</strong> energetic than<br />

Mollusca (A<strong>in</strong>ley et al., 2003). Cephalopods of Lolig<strong>in</strong>idae, were not fully identified to species level, s<strong>in</strong>ce the food capture process sometimes has difficulties <strong>in</strong> identify<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> quantify<strong>in</strong>g<br />

food items, which may cause some bias <strong>in</strong> the results (Duffy & Jackson, 1986).<br />

The species that stood out <strong>in</strong> the diet of Cape Verde Shearwater <strong>in</strong> 2012 was the Horse-Eye Jack, with 38%. The spawn<strong>in</strong>g period of this species occurs ma<strong>in</strong>ly between October <strong>and</strong><br />

December, co<strong>in</strong>cid<strong>in</strong>g with the time of sampl<strong>in</strong>g, which may correspond to a greater availability of this prey. However, <strong>in</strong> 2013, sard<strong>in</strong>es represented 61% of chicks diet, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that the<br />

Cape Verde shearwater changes diet accord<strong>in</strong>g to food availability. There were no important differences <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terpretation of analyzes of the frequency of occurrence <strong>and</strong> number, which<br />

was fairly expected because, accord<strong>in</strong>g to Zavala-Cam<strong>in</strong> (1996), numerical frequency is a direct consequence of occurrence, as it is only possible to count what was identified.<br />

Despite the reduced frequency of occurrence <strong>and</strong> number, the high energy of the cells <strong>in</strong>dicates a greater role of these organisms <strong>in</strong> feed<strong>in</strong>g the shearwater chicks. With regard to biometric<br />

data, the data obta<strong>in</strong>ed was expected, this is because Cape Verde shearwater chicks have a much higher weight <strong>in</strong> the early stages of development, but as they grow they beg<strong>in</strong> to lose<br />

weight until they are able to fly.<br />

Bibliography:<br />

AINLEY, D., BALLARD, G., BARTON, K., KARL, B., RAU, G., RIBIC, C., WILSON, P. 2003. Spatial <strong>and</strong> temporal variation of the Adélie pengu<strong>in</strong>s. The<br />

Condor, 105: 95–106 pp;<br />

HAZEVOET, C.J. (1995). The Birds of the Cape Verde Isl<strong>and</strong>s. British Ornithologists’ Union. B.O.U. Check-list nº13. 192 ;<br />

DUFFY, D. E JACKSON, S. (1986). Diet studies of <strong>seabird</strong>s: a review of methods. Colonial Waterbirds 9: 1-17; ZAVALA-CAMIN, L.A. (1996).<br />

Introduction studies on natural food <strong>in</strong> Peixes.Mar<strong>in</strong>gá, EDUEM, Mar<strong>in</strong>ga. 129P.<br />

With the f<strong>in</strong>ancial support of MAVA Foundation

2 nd World Seabird Conference<br />

“Seabirds: Global Ocean Sent<strong>in</strong>els”<br />

26-30 October 2015 Cape Town, South <strong>Africa</strong><br />

ANALYSIS OF MONITORING METHODS OF SEABIRD COMMUNITIES<br />

ON RASO ISLET, CAPE VERDE (P2-H-173)<br />

Almeida, Nathalie 1 ; Paiva, Vitor 2 ; Ramos, Jaime 2 ; Geraldes, Pedro 3 ; Fortes ,Isabel 1 ; Melo, Tommy 1 ; Rabaça, João 4<br />

1<br />

Biosfera I, Cape Verde, www.biosfera1.com; 2 Coimbra University; 3 SPEA, Portugal, www.spea.pt; 4 Évora University<br />

Raso Islet is an authentic sanctuary for <strong>seabird</strong>s; some of them endemic to Cape Verde. In this present work we studied the populations of pelagic <strong>seabird</strong>s (Procelariiforms) of Calonectris<br />

edwardsii (Oustalet, 1883) Cape Verde Shearwaters <strong>and</strong> Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulwerii, (Jard<strong>in</strong>e & Selby, 1828) from the islet. The current size of the shearwater population is not very well<br />

known, as well as the impact of cont<strong>in</strong>uous illegal kill<strong>in</strong>g of juveniles. Given that the majority of the world population of this species is <strong>in</strong> Santa Luzia <strong>and</strong> Branco <strong>and</strong> Raso Islets MPA, it is<br />

essential to know the size of the breed<strong>in</strong>g population (Lecoq, 2009), as well as the Bulwer’s Petrel population s<strong>in</strong>ce we found no literature related to recent census for the Cape Verde isl<strong>and</strong>s.<br />

Cape Verde Shearwater<br />

Fig. 1 – Geographic location of Raso Islet.<br />

Bulwer’s Petrel<br />

From August - November, we used a series of fixed-po<strong>in</strong>t circular plots (total plot area = 706.50 m 2 )<br />

count<strong>in</strong>g holes with chicks/parents/eggs of the target species. The islet (Fig. 1) was then mapped<br />

<strong>and</strong> divided <strong>in</strong>to UTM squares, where 28 plots were r<strong>and</strong>omly distributed <strong>in</strong> representative areas of<br />

the colonies (Fig. 2) predict<strong>in</strong>g nest densities for a comb<strong>in</strong>ation of environmental variables<br />

described, through multiple regression, <strong>and</strong> then resorted to extrapolation with the colony area to<br />

obta<strong>in</strong> a population estimate <strong>and</strong> compare with other data from previous studies.<br />

In 209 detections of active nests <strong>in</strong> 2013 (Fig. 3), we obta<strong>in</strong>ed NLLR <strong>and</strong> PVEG as the most<br />

significant characteristics (Table 1) for predict<strong>in</strong>g densities of B. bulwerii, as it breeds more <strong>in</strong> coastal<br />

rav<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> rocky walls <strong>in</strong> the islet <strong>in</strong>terior, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> areas where there is presence of vegetation,<br />

function<strong>in</strong>g as cover for the rocks <strong>and</strong> cavities where they occur. For C. edwardsii, PVEG is most<br />

important <strong>and</strong> significant (Table 2); act<strong>in</strong>g as a form of protection aga<strong>in</strong>st nest floods, reduc<strong>in</strong>g their<br />

impact <strong>and</strong> prevent<strong>in</strong>g rock l<strong>and</strong>slides, caus<strong>in</strong>g chick mortality.<br />

20<br />

15<br />

Nº of nests<br />

10<br />

5<br />

CMYK - blue to green<br />

0<br />

P1<br />

P2<br />

P3<br />

P4<br />

P5<br />

P6<br />

P7<br />

P8<br />

P9<br />

P10<br />

P11<br />

P12<br />

P13<br />

P14<br />

P15<br />

P16<br />

P17<br />

P18<br />

P19<br />

P20<br />

P21<br />

P22<br />

P23<br />

P24<br />

P25<br />

P26<br />

P27<br />

P28<br />

Nº of Plots<br />

Fig. 3 Number of Calonectris edwardsii (Green) <strong>and</strong> Bulweria bulwerii (blue) nests for each plot.<br />

Fig. 2 –Calonectris edwardsii) ; unoccupied areas (brown) ;colonies (yellow) 28 plots (green).<br />

Source: Lecoq, 2009<br />

Coefficients!<br />

Statistics!<br />

F<strong>in</strong>al<br />

Model! !<br />

SE!<br />

T! P!<br />

Constant! -0,041! 0,020! -2,066! 0,049!<br />

VEGP! 0,026! 0,008! 3,172! 0,004!<br />

NLLR! 0,020! 0,009! 2,102! 0,046!<br />

Table 1 – Coefficients <strong>and</strong> statistics of selected<br />

parameter <strong>in</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>al expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g model of the<br />

density of Bulweria bulwerii. VEGP –<br />

Vegetation Percentage. NLLR – Number of<br />

Large Loose Rocks.<br />

Coefficients<br />

Statistics<br />

F<strong>in</strong>al Model ! SE T P<br />

Constant 0,060 0,023 6,326

2 nd World Seabird Conference<br />

“Seabirds: Global Ocean Sent<strong>in</strong>els”<br />

P1-B-16<br />

26-30 October 2015 Cape Town, South <strong>Africa</strong><br />

ANALYSIS OF CHICK CONDITION OF CASPIAN TERNS COLONY<br />

BREEDING IN THE SALOUM DELTA NATIONAL PARK, SENEGAL<br />

Stanislas MALOU, stanislas.malou@yahoo.fr<br />

MSc. student , Ecology <strong>and</strong> Ecosystem Managment, University Cheikh Anta Diopof Dakar, Senegal<br />

Animal Biology Department<br />

Cheikh Anta Diop University of<br />

Dakar, Senegal (UCAD)<br />

L<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g structural parameters of growth-to-body mass of <strong>seabird</strong> chicks is a way to assess body condition. Condition is a sensitive measure for prey availability <strong>and</strong> can be used to assess the <strong>in</strong>fluence of<br />

environmental factors (fisheries, weather, SST, etc.). Several methods to calculate condition have been used <strong>in</strong> Saloum Delta NP, Senegal, s<strong>in</strong>ce 1998 (Veen et al. (2003), Klaassen (2008) <strong>and</strong> Lubbe et al. (2014),<br />

but each method has advantages <strong>and</strong> drawbacks. The current study uses Caspian Terns Hydroprogne caspia as a model species to compare these three (3) different methods, <strong>and</strong> suggests which method should<br />

be used for calculat<strong>in</strong>g body condition for long-term monitor<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

The methods compared <strong>and</strong> Results<br />

From 1998 till 2015, head + bill length (mm) <strong>and</strong> body mass (g) of Caspian Tern chicks of all ages were measured <strong>in</strong> Saloum Delta National Park, Senegal, by us<strong>in</strong>g Vernier callipers <strong>and</strong> electronic weigh<strong>in</strong>g scales.<br />

The data was subsequently analyzed by apply<strong>in</strong>g the three (3) different methods as proposed by Veen et al. (2003) 1 , Klaassen (2008) 2 <strong>and</strong> Lubbe et al. (2014) 3 .<br />

The Veen method use the similar growth logistic model: y = A/(1+exp(-K*(x-T))). A, K, T are parameters that need to be estimated. It is the relation between body mass (y) <strong>and</strong> bill+head (x). However, this growth<br />

logistic model corresponds to the maximal growth l<strong>in</strong>e (100%) <strong>and</strong> the lower growth l<strong>in</strong>e corresponds to 48% of the maximal.<br />

The Klaassen method considers mass dependent on structural measures. For the relation between body mass (M) <strong>and</strong> bill+head (H), it assumed a growth logistic model: M = A/(1+bexp[-kH], where A, b, k are<br />

parameters that need be estimated. Thus, for each <strong>in</strong>dividual a mass <strong>in</strong>dex was calculated us<strong>in</strong>g: -ln(A/M-1), which, accord<strong>in</strong>g to the logistic growth model, should yield a straight <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>e with bill+head.<br />

The Lubbe method use the quantile regression technique. Quantile regression is a method for estimat<strong>in</strong>g functional relationships betwen variables for all portions of a probability distribution. Quantiles 0.02 <strong>and</strong><br />

0.98 are chosen to estimate the lower <strong>and</strong> upper l<strong>in</strong>e respectively.<br />

Figure 2 (Klaassen method) shows a highly significant relationship between mass-<strong>in</strong>dex <strong>and</strong> bill head. This relationship also appears to be l<strong>in</strong>ear regression. The same observation appeared <strong>in</strong> Figure 3 (Lubbe<br />

method) but Figure 1 (Veen method) shows non-l<strong>in</strong>ear regression. The Klaassen <strong>and</strong> the Veen methods allow all data to be used. The Klaassen method cannot show good <strong>and</strong> the bad chick condition but the<br />

Veen method evaluates both good <strong>and</strong> bad chick condition. Indeed, this method shows the upper l<strong>in</strong>e (100%), which corresponds to good chick condition, <strong>and</strong> the lower l<strong>in</strong>e (48%) correspond<strong>in</strong>g to bad chick<br />

condition but the ma<strong>in</strong> disadvantage of Veen’s approach is the fitt<strong>in</strong>g of an upper l<strong>in</strong>e by eye. Veen et al. (2003) considered the lower limit of growth to be 48% of the maximal growth l<strong>in</strong>e (Lubbe et al., 2014).<br />

CMYK - blue to green<br />

However, the Lubbe method uses the quantile regression technique to fit the equivalent Veen et al.’s (2003) maximal growth l<strong>in</strong>e. This method is statistically based: Heteroscedasticity test or Breusch-Pagan/Cook-<br />

Weisberg test (chi2 = 23.59, p-value = 0.0000). This test shows the quantile regression technique is the best way to evaluate chick condition. The ma<strong>in</strong> disadvantage of this approach depends on the rigour of its<br />

study; the choice of extreme quantiles is different.<br />

Scatterplot of Mass Index aga<strong>in</strong>st BillHead; categorized by year<br />

Condition chicks 1998-2007 all data MK 17v*1748c<br />

800<br />

1<br />

Include condition: v3="CT"<br />

5<br />

700<br />

0,48<br />

600<br />

1998<br />

1999<br />

4<br />

3<br />

Weight (g)<br />

500<br />

400<br />

300<br />

2000<br />

2001<br />

2003<br />

2004<br />

Mass Index<br />

2<br />

1<br />

0<br />

200<br />

100<br />

0<br />

40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120<br />

2005<br />

2011<br />

2012<br />

2013<br />

2014<br />

-1<br />

-2<br />

-3<br />

-4<br />

40 60 80 100 120 140<br />

year: 1998<br />

year: 1999<br />

year: 2000<br />

year: 2001<br />

year: 2003<br />

year: 2004<br />

year: 2005<br />

year: 2006<br />

BillHead (mm)<br />

BillHead<br />

Figure 1 : Chick condition of Caspian Terns (Veen method) Figure 2 : Chick condition of Caspian Terns (Klaassen method) Figure 3 : Chick condition of Caspian Terns (Lubbe method)<br />

The quantile regression technique (Lubbe method) seems to be the best way to estimate chick condition. It is important to explore more methods, before a f<strong>in</strong>al conclusion.<br />

1<br />

Veen, J., Peeters, J., leopold, M. P., Van Damme, C. J. G. & Veen, T. 2003. Les oiseaux piscivores comme <strong>in</strong>dicateurs de la qualité de l’environnement mar<strong>in</strong>: suivi des effets de la pêche littorale en Afrique du Nord-Ouest. Alterra-rapport 666, ISSN 1566-7197, 190p.<br />

2<br />

Klaassen, M. An analysis of the condition of the chicks of <strong>West</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>n colony breed<strong>in</strong>g birds: data on terns <strong>and</strong> gulls from Senegal collected <strong>in</strong> the period 1998-2006. Unpublished.<br />

3<br />

Lubbe, A., UnderhillL, G., Waller, L. J. & Veen, J. 2014. A condition <strong>in</strong>dex for <strong>Africa</strong>n pengu<strong>in</strong> Spheniscus demersus chicks. <strong>Africa</strong>n Journal of Mar<strong>in</strong>e Science, University of Cape Town Libraries: Taylor & Francis. ISSN 1814-232X. 12p.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

This research was based on collaboration between Cheikh Anta Diop University <strong>and</strong> the <strong>Alcyon</strong> <strong>Project</strong>, funded by the MAVA Foundation <strong>and</strong> coord<strong>in</strong>ated by FIBA until<br />

December 2014, <strong>and</strong> BirdLife International (from January 2015 onwards). We thank both <strong>in</strong>stitutions for grant<strong>in</strong>g us <strong>in</strong>ternships at PNDS. Thanks are also due to Jan Veen &<br />

Wim C. Mullié for provid<strong>in</strong>g the body condition data collected from 1998 to 2014.<br />

With the f<strong>in</strong>ancial support of MAVA Foundation

2 nd World Seabird Conference<br />

“Seabirds: Global Ocean Sent<strong>in</strong>els”<br />

P1-B-26<br />

26-30 October 2015 Cape Town, South <strong>Africa</strong><br />

FOOD ECOLOGY OF CASPIAN TERNS DURING THE NESTING PERIOD<br />

IN THE NATIONAL PARK OF SALOUM DELTA, SENEGAL<br />

Sokhna Momie THIAW, sokhnamomie@gmail.com<br />

MSc. Student, Ecology <strong>and</strong> Ecosystem Management, University Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar, Senegal<br />

Animal Biology Department<br />

University Cheikh Anta Diop of<br />

Dakar, Senegal (UCAD)<br />

The Canary Current upwell<strong>in</strong>g system along the <strong>West</strong>-<strong>Africa</strong>n coast (Bellemans, 1988) is extremely rich <strong>in</strong> fish which attracts piscivorous colonial <strong>seabird</strong>s. These birds breed on isl<strong>and</strong>s from Mauritania <strong>in</strong> the north to Gu<strong>in</strong>ea<br />

<strong>in</strong> the south. The Delta Saloum <strong>in</strong> Senegal; a wetl<strong>and</strong> of <strong>in</strong>ternational importance (Dia, 2003), harbours important colonies of Sternidae <strong>and</strong> Laridae. Three (3) species, Royal <strong>and</strong> Caspian Term, & Slender-billed Gull) were<br />

chosen as <strong>in</strong>dicators <strong>in</strong> a long-term monitor<strong>in</strong>g programme (started <strong>in</strong> 1998) to obta<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation about prey-availability <strong>and</strong> related environmental factors <strong>in</strong> the <strong>West</strong>-<strong>Africa</strong>n <strong>mar<strong>in</strong>e</strong> environment (Veen et al. 2003, Mullié et<br />

al. this conference). The current study deals with the feed<strong>in</strong>g ecology of the Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia; further CT) <strong>in</strong> Saloum Delta National Park, Senegal, for two months from April - June 2014.<br />

An enclosure around 13<br />

nests was used to assess<br />

food provision<strong>in</strong>g of chicks<br />

by direct observations. The<br />

length of the prey was<br />

estimated by comparison<br />

with Caspian Tern bill<br />

length. Observations were<br />

made from 7 am to 7 pm.<br />

Faeces <strong>and</strong> regurgitated<br />

pellets were collected to<br />

identify the fish otoliths<br />

they conta<strong>in</strong>ed. Three (3)<br />

Caspian Tern breed<strong>in</strong>g<br />

next to the enclosure<br />

were equipped with UVA-<br />

BiTS data loggers.<br />

Individual! Period! beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g! End! Distance <strong>in</strong><br />

km!<br />

Abdou<br />

logger<br />

2075!<br />

Moussa<br />

logger<br />

2062!<br />

Nicolas<br />

logger<br />

2063!<br />

Incubation! 05/05/2014<br />

!<br />

Chick<br />

Rear<strong>in</strong>g<br />

!<br />

17/05/2014<br />

!<br />

Incubation! 27/04/2014<br />

!<br />

Chick<br />

Rear<strong>in</strong>g<br />

!<br />

Incubation<br />

!<br />

Chick<br />

Rear<strong>in</strong>g<br />

!<br />

16/05/2014<br />

!<br />

27/04/2014<br />

!<br />

13/05/2014<br />

!<br />

16/05/<br />

2014<br />

!<br />

27/05/<br />

2014<br />

!<br />

15/05/<br />

2014!<br />

27/05/<br />

2014<br />

!<br />

09/05/<br />

2014<br />

!<br />

19/05/<br />

2014<br />

!<br />

73 ± 14,8<br />

(14,5-174)<br />

!<br />

39 ± 4<br />

(0,13 - 99)<br />

!<br />

83,6± 48<br />

(26 – 183)<br />

!<br />

42,2 ± 4,8<br />

(14– 11)!<br />

90 ± 18<br />

(0,3-170)<br />

!<br />

46 ± 4<br />

(12-108)<br />

!<br />

Duration of<br />

out H!<br />

4:01± 0:49<br />

(0:37-8:41) !<br />

1 :27±0:08<br />

(0:36-3:53)!<br />

4:34±0:51<br />

(1:149:32)!<br />

2:18±0:17<br />

(0:34-6:26)<br />

!<br />

4:28± 0:46<br />

(1:33-8:00)<br />

!<br />

1:35 ± 0:07<br />

(0:42-3:31)<br />

!<br />

Distance<br />

colony!<br />

34 ± 21<br />

(10 – 63)!<br />

15 ± 13<br />

(3 – 54)!<br />

27 ± 10<br />

(13 - 42)!<br />

12 ± 7<br />

(1 - 25)!<br />

40 ± 25<br />

(12–102)!<br />

16 ± 11<br />

(4 – 53)!<br />

Duration of<br />

food!<br />

2:33 ± 2:01<br />

(0:08 - 1:27)!<br />

0:35 ± 0:25<br />

(0:08- 6:00)!<br />

2:46 ± 2 :00<br />

(0:35- 6:26)!<br />

1:12 ± 1:01<br />

(0:08- 4 :49)!<br />

2:34 ± 1:34<br />

(0 :04 - 0:59)!<br />

0:23 ± 0:17<br />

(0 :44 - 5 :11)!<br />

N!<br />

N/J!<br />

14! 1!<br />

30! 3!<br />

10! 1!<br />

20! 3!<br />

9! 1!<br />

23! 3!<br />

Number of prey<br />

Frequency distribution of prey brought to the chicks<br />

45<br />

40<br />

35<br />

Frequency of prey <strong>in</strong> %<br />

30<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

CMYK - blue to green<br />

0<br />

0 to 5 5 to 10 10 to 15 15 to 20 20 to 25 25 to 30<br />

Size of the preys <strong>in</strong> cm<br />

Forag<strong>in</strong>g distances dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the <strong>in</strong>cubation <strong>and</strong> chick<br />

rear<strong>in</strong>g period.<br />

Forag<strong>in</strong>g durations<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>cubation <strong>and</strong><br />

chick rear<strong>in</strong>g period<br />

Prey composition (fish families) <strong>in</strong> pellets of Caspian Terns, collected<br />

<strong>in</strong> the experimental enclosure dur<strong>in</strong>g the breed<strong>in</strong>g saison<br />

Based on the otoliths recovered, the Caspian Tern <strong>in</strong> the enclosure preyed upon 24 fish species.<br />

The average size of prey fed to the chicks <strong>in</strong>creased from 1 to 30 cm.<br />

Incubat<strong>in</strong>g birds made fewer, but longer forag<strong>in</strong>g trips (N= 1/day, avg. distance 50 to 100 km) than<br />

birds with chicks (N=3/day, avg. distance 4 to 18 km).<br />

Birds showed a peak <strong>in</strong> forag<strong>in</strong>g activities <strong>in</strong> the morn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> a less pronounced peak at the end of<br />

the afternoon<br />

References<br />

Caspian Terns proved to be an excellent model species as they were quite <strong>in</strong>sensitive to h<strong>and</strong>l<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong><br />

disturbance <strong>in</strong> the enclosure <strong>and</strong> allowed observations at close range. Direct observations of food<br />

provision<strong>in</strong>g of the chicks <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation with the analysis of faeces <strong>and</strong> pellets (Veen et al. 2002)<br />

provided quite an unbiased measure of their diet etc.<br />

The use of m<strong>in</strong>iaturized data-loggers provided a wealth of <strong>in</strong>formation on home ranges <strong>and</strong> feed<strong>in</strong>g<br />

areas, allow<strong>in</strong>g us to calculate the size of home ranges; water depths <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> their feed<strong>in</strong>g ranges;<br />

distances covered; <strong>and</strong> maximum time <strong>and</strong> distance from the nest without time-<strong>in</strong>tensive observations.<br />

M. Bellemans, A. Sagna, W. Fischer et N. Scialabba, 1988, fiche FAO d’identification des espèces pour les beso<strong>in</strong>s de la pêche, guide des ressources halieutiques<br />

du Sénégal et de la Gambie (espèces <strong>mar<strong>in</strong>e</strong>s et d’eaux saumâtres), 227p.<br />

Dia.I.M(2003). Elaboration et mise en œuvre d’un plan de gestion <strong>in</strong>tégrée : La Reserve de Biosphere du Delta du Saloum, 130p.<br />

Morel, G, Roux. F (1974). Les migrateurs paléarctiques. Extrait de la Terre et la Vie, Revue d’Ecologie Appliquée Volume 27, 1973 : p. 523-550.<br />

Veen, J., Peeters, J., Leopold, M.F., Van Damme, C.J.G. & Veen, T. 2003. Les oiseaux piscivores comme <strong>in</strong>dicateurs de la qualité de l’environnement mar<strong>in</strong>: suivi<br />

des effets de la pêche littorale en Afrique du Nord-Ouest. Alterra report 666: 1-190.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

This study was f<strong>in</strong>anced by the MAVA foundation <strong>in</strong> the frame of the <strong>Alcyon</strong> <strong>Project</strong>. Just<strong>in</strong>e Dossa, Wim<br />

Mullié, Jan Veen, Ibnou NDIAYE & Cheikh Tidiane gave helpful orgnizational <strong>and</strong> scientific support. Also<br />

Stanislas MALOU my partner <strong>in</strong> this research. Thanks are due to all of them.<br />

Locations where forag<strong>in</strong>g activities of three birds with<br />

GPS data-loggers were concentrated<br />

With the f<strong>in</strong>ancial support of MAVA Foundation

2 nd World Seabird Conference<br />

“Seabirds: Global Ocean Sent<strong>in</strong>els”<br />

26-30 October 2015 Cape Town, South <strong>Africa</strong><br />

K@LM!KNK8C!KOM%ON%!PL%NOQCRKMR%CQLCS%ON%!PL%8CTL%9LQ@L%SPLCQBC!LQ%!"#$%&!'()*+&,-"(,*))+<br />

BK!P%RTS-UORRLQS%%-$#'$,)64%/,>#/2%+1%*$1D,(,1)%+"#,$%0",0>(%&,+"%'%;1$#%7,D#$(,E#7%')7%:#H#$%I.'/,+2%7,#+%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

%<br />

!!<br />

%"C!#!$%&'!(')*'!+,'%)-%.')+!/0)%1231!)'1203+!*4)231!23546%703!"684'#!%3*!5,259:)'%)231!")'*#!!<br />

!"J#!0.,')!+'%62)*+;!"8#!?+!%3*!"@#!@+,')2'+!<br />

CMYK - blue to green<br />

K)0W%X=XY%<br />

8QW%X=XY%<br />

K)0W%\=_Y%<br />

8QW%_=]Y%<br />

K)0W%`^=`Y%<br />

8QW%a=[Y%<br />

"?#! [0)%1231!)'1203+!"\]^!9')3'8!_`#!0/!$%&'!(')*'!+,'%)-%.')+!!"#$%&'()*+,&-.")-+**!*4)231!23546%703!"684'!&08D103+R!a!b!<br />

c]!.)2&+!/)0%35!`f?)1423R!W!P!$%&:(').;!`%9%);!I'3'1%8!<br />

">#! [0)%1231! *2+.)264703! 0/! a0).,')3! 1%33'.+! B0)4+! 6%++%34+! "*%)9! &239! 823'#! %3*! I50&082f+! +,'%)-%.')+! $%803'5.)2+!<br />

*208%35R!V!P!I04.,')3%35!<br />

%<br />

`f?)1423R!W!P!$%&:(').;!`%9%);!I'3'1%8H!<br />

%">#! ?)'%+!0/!U'+.)25.'*!I'%)5,!k03'+!"?UIR!52)58'+#!0/!62)*+!23!V]SW!"684'#!%3*!V]Sc!")'*#H!$2)58'+!)'&)'+'3.!.,'!<br />

%<br />

?UI!k03'+!-2.,!

2 nd World Seabird Conference<br />

“Seabirds: Global Ocean Sent<strong>in</strong>els”<br />

26-30 October 2015 Cape Town, South <strong>Africa</strong><br />

ABUNDANCE, BREEDING PHENOLOGY AND SUCCESS OF THE RED-BILLED TROPICBIRD<br />

(Phaethon aethereus) IN MADELEINE ISLAND (DAKAR, SENEGAL)<br />

Ngoné Diop 1 2 Cheikh Tidiane Ba 1 Papa Ibnou Ndiaye 1 Jacob González-Solís 2<br />

1. Department of Animal Biology, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Av Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar, Senegal<br />

2. Institut de Recerca de la Biodiversitat (IRBio) <strong>and</strong> Department de Biologia Animal, Universitat de Barcelona,<br />

Av Diagonal 643, Barcelona 08028, Spa<strong>in</strong><br />

Rationale<br />

Red-billed tropicbirds (Phaethon aethereus) (fig. 1) occur across tropical waters of the Atlantic <strong>and</strong><br />

Pacific Oceans, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the north Indian Ocean (Orta,1992). It holds approximately 2,000 pairs <strong>in</strong> the<br />

western north Atlantic <strong>and</strong> less than 8,000 pairs globally (Lee & Walsh-McGehee, 2000). In western<br />

<strong>Africa</strong>, It breeds only <strong>in</strong> Cape Verde <strong>and</strong> Senegal, but none of these two populations have been<br />

well studied so far. In Senegal, the species holds only one breed<strong>in</strong>g site <strong>in</strong> the Madele<strong>in</strong>e Isl<strong>and</strong>, a<br />

small un<strong>in</strong>habited volcanic isl<strong>and</strong> just 4km off Dakar (fig. 2).<br />

Fig. 1: Red-billed tropicbird bird on nest<br />

Methods<br />

We monitored nests content every 15 days<br />

from June 2014 to July 2015.<br />

Results<br />

Hatch<strong>in</strong>g success= eggs hatched / eggs laid<br />

Fledg<strong>in</strong>g success= chicks fledged / eggs hatched<br />

Breed<strong>in</strong>g success= chicks fledged / eggs laids<br />

Fig. 2: Location of Madele<strong>in</strong>e Isl<strong>and</strong><br />

Abundance <strong>and</strong> Breed<strong>in</strong>g periodicity<br />

Breed<strong>in</strong>g success <strong>and</strong> nest mortality<br />

Red-billed tropicbird was present all year Hatch<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> fledg<strong>in</strong>g success was estimated<br />

round <strong>in</strong> Madele<strong>in</strong>e Isl<strong>and</strong> (fig. 3). The 77,96 <strong>and</strong> 73,91 respectively (fig. 5).<br />

number of active nests (nest with an egg or a Overall breed<strong>in</strong>g success was 57.6% (n=59<br />

chick) <strong>in</strong>creased from October to January, nests).<br />

reach<strong>in</strong>g 41 nests <strong>and</strong> 40 adults on the<br />

isl<strong>and</strong> (fig. 3). Females laid a s<strong>in</strong>gle egg<br />

once a year. Lay<strong>in</strong>g peak was <strong>in</strong> January (19<br />

eggs) <strong>and</strong> first hatch<strong>in</strong>g occurred <strong>in</strong><br />

CMYK - blue to green<br />

November (fig. 4).<br />

Discussion<br />

The breed<strong>in</strong>g cycle of red-billed tropicbirds <strong>in</strong> Madele<strong>in</strong>e Isl<strong>and</strong> is similar to that described <strong>in</strong><br />

Ascension (Stonehouse, 1962) but differs from the cycle described for the same species <strong>in</strong> the<br />

Gulf of California, where seasonality is more marked (from November to June, Castillo-Guerrero et<br />

al. 2011). Breed<strong>in</strong>g success <strong>in</strong> Madele<strong>in</strong>e Isl<strong>and</strong> (58%) is similar to that reported <strong>in</strong> Ascension<br />

Isl<strong>and</strong> (51%, Stonehouse1962) <strong>and</strong> greater than that reported from St Helena (11%, Beard et al.<br />

2013).<br />

Fig. 3: Abundance of adults <strong>and</strong> nests<br />

In summary, red-billed tropicbird <strong>in</strong> Madele<strong>in</strong>e Isl<strong>and</strong> hold a small <strong>and</strong> vulnerable<br />

population, breed<strong>in</strong>g meanly <strong>in</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter, although some breeders can be found throughout<br />

the year. Currently, breed<strong>in</strong>g success is relatively high.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

•!<br />

•!<br />

Beard A., Cl<strong>in</strong>gham E., Henry L. 2013. St helena <strong>seabird</strong>s report.<br />

Castillo-Guerrero J.A.,Guevara-Med<strong>in</strong>a M.A. &Mell<strong>in</strong>k E. 2011. Bred<strong>in</strong>g ecology of the red-billed tropicbird Phaethon aethereus under<br />

contrast<strong>in</strong>g environmental conditions <strong>in</strong> the Gulf of California.Ardea99:61-71.<br />

•! Lee D.S & Walsh-McGehee M. 2000. Population estimates, conservation concerns , <strong>and</strong> management of tropicbirds <strong>in</strong> the western<br />

Atlantic.Carribb.J. Sci. 36: 267-279.<br />

•! Orta J. 1992. Castillo-Guerrero J.A.,Guevara-Med<strong>in</strong>a M.A. & Mell<strong>in</strong>k E. 2011. Bred<strong>in</strong>g ecology of the red-billed tropicbird Phaethon aethereus<br />

under contrast<strong>in</strong>g environmental conditions <strong>in</strong> the Gulf of California.Ardea99:61-71.<br />

•! Stonehouse B. 1962. The tropicbirds (Genus Phaethon) of Ascension Isl<strong>and</strong>. Ibis 103: 124-161<br />

Fig. 4: Breed<strong>in</strong>g phenology<br />

90%<br />

80%<br />

70%<br />

60%<br />

50%<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

This work was conducted as part of <strong>Alcyon</strong> project funded by MAVA <strong>and</strong> implemented<br />

by FIBA !<strong>and</strong> thereafter by BirdLife International. We thank the staff of the national park<br />

of Madele<strong>in</strong>e Isl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Paul Rob<strong>in</strong>son for their support.<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

0%<br />

hatch<strong>in</strong>g success fledg<strong>in</strong>g success breed<strong>in</strong>g success<br />

Fig. 5: Reproductive success<br />

With the f<strong>in</strong>ancial support of MAVA Foundation