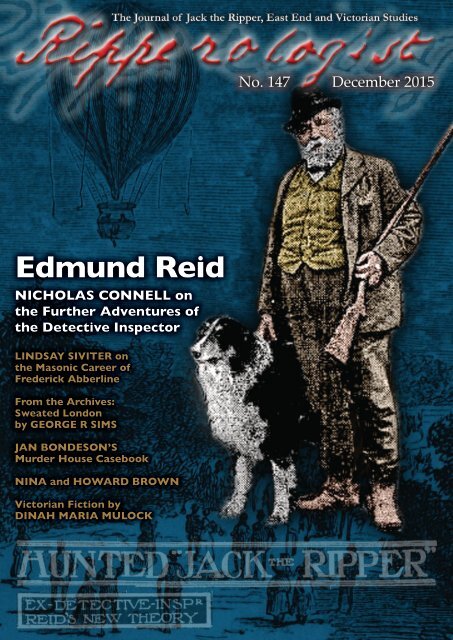

Edmund Reid

nuhf574

nuhf574

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

No. 147 December 2015<br />

<strong>Edmund</strong> <strong>Reid</strong><br />

NICHOLAS CONNELL on<br />

the Further Adventures of<br />

the Detective Inspector<br />

LINDSAY SIVITER on<br />

the Masonic Career of<br />

Frederick Abberline<br />

From the Archives:<br />

Sweated London<br />

by GEORGE R SIMS<br />

JAN BONDESON’S<br />

Murder House Casebook<br />

NINA and HOWARD BROWN<br />

Victorian Fiction by<br />

DINAH MARIA MULOCK<br />

Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1

Quote for the month<br />

“Seriously I am amazed at some people who think a Pantomime of Jack the Ripper is okay. A<br />

play by all means but a pantomime? He was supposed to have cut women open<br />

from throat to thigh removed organs also laid them out for all to see.<br />

If that’s okay as a pantomime then lets have a Fred West pantomime or<br />

a Yorkshire Ripper show.”<br />

Norfolk Daily Press reader Brian Potter comments on reports of a local production. Sing-a-long songs include “Thrash Me Thrash Me”.<br />

Ripperologist 147<br />

December 2015<br />

EDITORIAL: THE ANNIVERSARY WALTZ<br />

by Adam Wood<br />

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF<br />

DETECTIVE INSPECTOR EDMUND REID<br />

by Nicholas Connell<br />

BROTHER ABBERLINE AND<br />

A FEW OTHER FELLOW NOTABLE FREEMASONS<br />

by Lindsay Siviter<br />

JTR FORUMS: A DECADE OF DEDICATION<br />

by Howard Brown<br />

FROM THE ARCHIVES:<br />

SWEATED LONDON BY GEORGE R SIMS<br />

From Living London Vol 1 (1901)<br />

FROM THE CASEBOOKS OF A MURDER HOUSE DETECTIVE:<br />

MURDER HOUSES OF RAMSGATE<br />

by Jan Bondeson<br />

A FATAL AFFINITY: CHAPTERS 5 & 6<br />

Nina and Howard Brown<br />

DEAR RIP<br />

Your letters and comments<br />

VICTORIAN FICTION:<br />

THE LAST HOUSE IN C-- STREET<br />

by Dinah Maria Mulock (Mrs Craik)<br />

REVIEWS Jack the Ripper- Case Solved, 1891 and more!<br />

EXECUTIVE EDITOR<br />

Adam Wood<br />

EDITORS<br />

Gareth Williams<br />

Eduardo Zinna<br />

REVIEWS EDITOR<br />

Paul Begg<br />

EDITOR-AT-LARGE<br />

Christopher T George<br />

COLUMNISTS<br />

Nina and Howard Brown<br />

David Green<br />

The Gentle Author<br />

ARTWORK<br />

Adam Wood<br />

Follow the latest news at<br />

www.facebook.com/ripperologist<br />

Ripperologist magazine is free of<br />

charge. To be added to the mailing list,<br />

send an email to contact@ripperologist.<br />

biz.<br />

Back issues form 62-146 are<br />

available in PDF format: ask at<br />

contact@ripperologist.biz<br />

To contribute an article, please email<br />

us at contact@ripperologist.biz<br />

Contact us for advertising rates.<br />

www.ripperologist.biz<br />

Ripperologist is published by Mango Books. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist<br />

are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and<br />

opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its<br />

editorial team, but do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the publisher.<br />

We occasionally use material we believe has been placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim<br />

ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement.<br />

The contents of Ripperologist No. 147, December 2015, including the compilation of all materials and the unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other<br />

items are copyright © 2015 Ripperologist/Mango Books. The authors of signed articles, essays, letters, news reports, reviews and other items retain the copyright of<br />

their respective contributions. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or otherwise circulated<br />

in any form or by any means, including digital, electronic, printed, mechanical, photocopying, recording or any other, without the prior permission in writing of<br />

Ripperologist. The unauthorised reproduction or circulation of this publication or any part thereof, whether for monetary gain or not, is strictly prohibited and may<br />

constitute copyright infringement as defined in domestic laws and international agreements and give rise Ripperologist to civil liability 118 and criminal January prosecution. 2011 2

The Anniversary Waltz<br />

EDITORIAL by ADAM WOOD<br />

The thing about anniversaries is that there’s something to be found when you need one. As we<br />

publish this edition of Ripperologist, on 31 December 2015, it’s 127 years to the day that Henry<br />

Winslade recovered the body of Montague Druitt from the Thames at Thornycroft’s torpedo works,<br />

Chiswick. And tomorrow will be the 126th anniversary of James Kelly’s escape from Broadmoor.<br />

It’s doubtful that Mark Galloway was contemplating these events when he hit upon the idea of bringing together likeminded<br />

people to meet and discuss the Ripper crimes over a pint or two, but that’s exactly what he did late in 1994.<br />

His most excellent plan quickly captured the imagination of many and the Cloak and Dagger Club was formed, with a<br />

ten-page Pilot Newsletter published to mark the first meeting on 3 December, making us 21-years-old this month. And<br />

boy, do we feel old...<br />

As the Club grew so did the newsletter, being renamed Ripperologist magazine with Issue 5, December 1995 - making<br />

it 20 years of publication under this name with Rip 147.<br />

And ten years ago this month we<br />

ran the gauntlet by relaunching as<br />

an electronic journal, our last print<br />

edition being Rip 61, September 2005.<br />

It’s fair to say reaction in the Ripper<br />

community was ‘mixed’, with many<br />

posts from the likes of ‘Outraged<br />

of Tunbridge Wells’ expressing<br />

their opinions on Stephen Ryder’s<br />

Casebook: Jack the Ripper site.<br />

By happy coincidence, 2016 sees<br />

Casebook itself celebrating its 20th<br />

birthday. Over the years Casebook<br />

launched many innovative, free<br />

platforms for Ripperologists such as the message boards, chatroom and the Jack the Ripper Wiki.<br />

While that site continues to house the largest collection of transcribed Ripper-related newspaper articles and other<br />

crucial content, perhaps the platform for most discussion today is JTRForums.com, run by Howard Brown and which -<br />

you’ve guessed it - in September this year celebrated an anniversary of its own, ten years since doors opened.<br />

Elsewhere in this issue, How Brown describes those heady early days and the well-oiled machine which is the message<br />

boards of JTRForums today.<br />

To finish this numbers-based editorial of exactly 1,888 words (it’s not really, but did you start counting?), here’s a look<br />

to the future... we’ll be publishing the 150th issue of Ripperologist in August 2016 - perfectly timed to coincide with<br />

the 128th anniversary of the Autumn of Terror. In fact, we anticipate publishing the special edition on the anniversary<br />

of Polly Nichols’ death.<br />

We’re planning something very special to mark the occasion, so keep reading future issues to make sure you don’t<br />

miss out... Finally, the team at Ripperologist wish every single one of our readers good health and happiness in the New<br />

Year. Thank you for your support over the past 21 years.<br />

Left to right: Pilot issue; the first electronic Ripperologist; our 100th edition<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 1

The Further Adventures<br />

of Detective Inspector<br />

<strong>Edmund</strong> <strong>Reid</strong><br />

By NICHOLAS CONNELL<br />

Since the publication of the last edition of The Man Who Hunted Jack the Ripper several new<br />

sources have come to light that provide new information on <strong>Edmund</strong> <strong>Reid</strong>, the former head of<br />

Whitechapel CID.<br />

Upon retiring in 1896 <strong>Edmund</strong> <strong>Reid</strong> was interviewed by several newspapers including the News of the World<br />

who boasted that their feature on his involvement in the Jack the Ripper investigation would ‘place before the<br />

public facts they never before learned, and to clear up a volume of curious misconceptions which were made by<br />

theorists, learned and unlearned, who took a deep interest in the crimes at the time of their committal.’<br />

The News of the World journalist justifiably described <strong>Reid</strong> as ‘one of the most remarkable men ever engaged in<br />

the business of detecting crime.’ They met at <strong>Reid</strong>’s home and when sat at the drawing-room table the journalist<br />

bluntly asked the detective: ‘Tell me all about the Ripper murders.’ 1 <strong>Reid</strong> responded by opening a cabinet drawer<br />

that contained ‘assassin’s knives, portraits, and a thousand and one curiosities of criminal association.’ Among<br />

the criminological ephemera was ‘probably the most remarkable photographic chamber of horrors in existence.’<br />

<strong>Reid</strong> owned a set of Jack the Ripper victim photographs which he spread out on the table before telling the tale<br />

of the Whitechapel murders:<br />

‘The first Ripper murder was one which is not<br />

generally associated with the series. This was<br />

the Brick-lane murder, committed on a bank<br />

holiday in 1888. A woman named Smith was met<br />

by a man in Brick-lane who carried a walkingstick,<br />

and committed a most terrible outrage<br />

upon her.’<br />

It is impossible to repeat the description of the<br />

outrage. <strong>Reid</strong> proceeded –<br />

News of the World, 12 April 1896<br />

‘The woman, strange to say, made no cry, and<br />

raised no alarm. She took a scarf from her<br />

neck, bound up the terrible wound, and quickly<br />

walked round to George’s-yard, some distance,<br />

and told some of her female friends what<br />

had happened. Seeing her fainting condition,<br />

these women took her walking to the London<br />

Hospital. Here she retained consciousness for<br />

some time, but could give no description of the<br />

man who assaulted her. She died the next day.<br />

This was the only woman who lived after seeing<br />

the Ripper. She could afford us no information<br />

about him.’<br />

1 Presumably the interview took place at Stepney Buildings, Stepney, the address given in <strong>Reid</strong>’s pension papers (PRO, MEPO 21/25).<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 2

So you never obtained a description of the man from anyone?<br />

‘Never. Indeed that the murderer was a man, is only an inference from the fact that no one but a person<br />

believed by the women themselves to be a man could have been taken by them to the secret haunts in<br />

which the murders were all committed.’<br />

All the murders were committed in secret haunts?<br />

‘Yes, all the murders were upon women of the most degraded class, and in the darkest, most secret<br />

places, inaccessible to the police, where the murderer was taken by the women themselves. This is<br />

an important point, in reviewing the crimes, that it was evident in every case the women themselves<br />

selected the place of their death. The murderer never took them to these places. He was always taken<br />

to them by his victims who knew and selected dark, hidden spots for their own purpose. This, also, is<br />

why I maintained always that respectable women never had anything to fear from the Ripper.’<br />

And the next murder?<br />

‘The next murder was the one which has been recorded as the first Ripper case. This was the notorious<br />

Buck’s-row murder. In this case the woman was believed to have been murdered about one o’clock in<br />

the morning. She was found with her throat cut and on the post-mortem examination taking place it<br />

was found that her body was [sic] been cut about in a brutal, haphazard manner with a knife.’<br />

And what connection had this case with the previous one?<br />

‘The answer to your question is an explanation of the whole theory of the murders. The idea that the<br />

murderer was a mad surgeon, or a man with any knowledge of the anatomy of the human being was a<br />

most ridiculously inaccurate one. The murderer was mad beyond a doubt – a homicidal maniac. He had<br />

no method, nor did he exhibit any acquaintance of the human frame. He was simply seized with a frenzy<br />

the moment he was alone with the women, hacked and tore at them in his frenzy, with no intent but<br />

the satisfaction of a horrible passion for destruction. There were other murders in the district during<br />

the period which were not Ripper murders.’<br />

And herein lay the distinction between the ordinary murders and the others, if I am right in putting<br />

the question so?<br />

‘The cases which I am discussing with you as the Ripper murders all displayed one peculiar form of<br />

violation and an interesting fact was that the hand of the one madman could be traced through a series<br />

of nine murders, each one displaying a gradation of more intensified frenzy. Every fresh time the mania<br />

seized the murderer his passion became more horrible in its satisfaction. The mutilation in the Buck’srow<br />

case was exactly of the same nature as that inflicted upon the woman who died in the hospital;<br />

but in the second and all succeeding cases the throat of the victim had been cut before the mutilation.<br />

Take another case. There was the George-yard murder. A cabman coming down the stairs of some<br />

dwellings at four o’clock in the morning found the body of a woman named Tabrun [sic] lying half in<br />

the doorway of a passage in the building. Her throat was cut and she had been stabbed in 39 places.<br />

She had been dead over two hours. The doctor who examined the body said the stabs appeared to have<br />

been inflicted with a bayonet. A woman known as Pearly Poll said she and Tabrun were in company the<br />

evening before with a private soldier and a corporal, and that the corporal went away with Tabrun. We<br />

had two parades at the Tower of London of the Coldstream Guards, and one at the Wellington Barracks.<br />

At each place Pearly Poll picked out a different man as the one she had seen, but in each case the books<br />

of the barracks proved that the men she picked out were indoors during the whole evening and night.<br />

As a matter of fact Pearly Poll was not a trustworthy witness. We never obtained any clue in this case,<br />

nor anyone in any subsequent case able to afford us the slightest information that was of use.<br />

To enable you to understand the difficulty surrounding the next case I need to explain that in the East<br />

End of London it is a common thing for men of means to farm houses. This is to say they rent houses in<br />

which they do not live themselves, and let out every room of a house to tenants of their own. The front<br />

door of such a house is always unbarred, and no person living on the premises has a right to interfere<br />

with anyone using the front doorway, or the passages or stairs. Yet the police have no power to enter,<br />

as the place is the private property of the absent landlord. Outcasts wander into these houses and<br />

sleep on the stairs and in the passages, and no one is empowered to remove them. A resident in one of<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 3

these houses in Hanbury-street went down at five o’clock in the morning into a yard at the rear of the<br />

place and found the body of a woman lying between some stone steps and a wall adjoining the side of<br />

the house. Her throat was cut in the same way as in the previous cases, and the ‘ripping’ to which the<br />

Buck’s-row woman’s body had been subjected had been inflicted upon this one. Again, there was a stage<br />

of increased ferocity. The ripping was far more severe upon the Hanbury-street woman. She had been<br />

dead some hours. No one knew anything about her. She was one of the outcasts. No one had seen her,<br />

no one had heard a person shout. Not a word in the locality could afford us the slightest information.<br />

The body of the woman had again been slashed and hacked about in the clumsiest possible manner.’<br />

The next murder described by <strong>Reid</strong>, as the horrible photograph came in its turn into his hand, was the<br />

Berner-street murder. As to this case he said –<br />

‘In this case a woman was found under curious circumstances with her throat cut. A man named<br />

Darnschitz [sic] kept a Socialist club, now extinct, in Berner-street. At the side of the club was a<br />

gateway, leading to a very dark yard. One Sunday night – a very dark night it was – Darnschitz, who had<br />

been out driving, arrived home about half-past twelve, and turned his pony through this gateway. A<br />

little distance up the yard the pony reared and refused to move forward. It had seen something, and,<br />

looking down, Darnschitz saw something move on the ground. He leaped out of the pony-carriage and<br />

ran into the club by a side door and called to his wife, who was in charge, and others. Lights were<br />

brought, and the body of a woman was found, with the throat cut and still bleeding. The pony must<br />

have seen the man at the moment the murder was being committed. During the short space of time the<br />

club proprietor had been bringing lights the murderer had sped like a shadow. No person could be found<br />

who had noticed anyone leave the yard.<br />

While the police were engaged making their inquiries into this case information was received that<br />

another murder had been committed in Mitre-square in the City. In a quiet, dark corner of Mitre-square<br />

we found the body of a woman with the throat cut, and her body mutilated in the same horrible manner<br />

as in the other cases. This woman’s nose and ears had been cut off, and her face slashed. This murder<br />

was committed in September 1889 or 90. I forget for the moment which year.’<br />

Was not this the writing on the wall case?<br />

‘Yes. I was coming to that. There is no doubt that when the fiend was disturbed by the pony and fled<br />

the mania was still running through his blood insatiate. He appears to have gone straight down Bernerstreet<br />

to Commercial-street, passed along to the City, met this woman whom he mutilated in Mitresquare,<br />

and there expended his mania upon the second victim. Thence he came back by a triangular<br />

route, and on the wall of a passage leading to some model dwelling in Goulston-street he wrote the<br />

words in chalk –<br />

‘The Jews shall not be blamed for this.’<br />

That this was the murderer’s writing was proved by the fact that thrown down on the ground beneath<br />

the writing was a piece of the apron of the woman murdered in Mitre-square. This was the only<br />

trustworthy specimen of the man’s writing we ever obtained, and this was rubbed off before it could<br />

be photographed, contrary to my wishes and much to my regret.’<br />

Detective <strong>Reid</strong>’s next account was of the Dorset-street murder –<br />

‘This was a case in which a pretty, fair-haired, blue-eyed, youthful girl was murdered. She rented a<br />

room in a house in Dorset-street, for which she paid 4s 6d a week rent. The room was badly furnished<br />

for the reason that her class of people always pawn or sell anything decent they ever get into their<br />

places. The curtains to the windows were torn and one of the panes of glass was broken. Kelly was in<br />

arrears with her rent and one morning a man known as ‘The Indian’ who was in the employment of the<br />

landlord of the house, went round about eight o’clock to see the woman about the money. Receiving<br />

no answer to his knock at the door, he peered through the window, and through the torn curtain saw<br />

the horrible sight of the woman lying on her bed hacked to pieces, and pieces of her flesh placed upon<br />

the table.<br />

I ought to tell you that the stories of portions of the body having been taken away by the murderer<br />

were all untrue. In every instance the body was complete. The mania of the murderer was exclusively<br />

for horrible mutilation. The landlord was brought round to the house by his man, and the sight of the<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 4

poor mutilated woman turned his brain. He became a perfect madman for weeks, and used to come at<br />

times and knock me up and cry out ‘Come on, come on, come out with me, we’ve got him, we’ve got<br />

the Ripper.’ Happily the man recovered his balance of mind in time, but the shock was terrible for him.<br />

The suggestion having been made that in the eyes of a murdered person a reflection of the murderer<br />

might be retained, we had the eyes of Kelly photographed and the photographs magnified, but the<br />

effort was fruitless. We tried every possible means of tracing if the woman had been seen with a man,<br />

but without avail.<br />

An example of the difficulty we had may be found in that women came forward who swore that they<br />

saw Kelly standing at the corner of the court at eight o’clock of the morning her body was found, but<br />

the evidence of the doctors proved this to be an impossibility. By that hour the woman had been dead<br />

not less than four hours.<br />

After the death of Kelly, which happened on Lord Mayor’s Day, by the way,’ said <strong>Reid</strong> who continued to<br />

make selections from his hideous photographs, ‘a year and eight months passed without our being again<br />

called out, and we began to hope the murders had ended. During this time, however, the new system<br />

of police patrol, which brought into use for the first time the India-rubber silent boots, and which<br />

necessitated one policeman always passing another, was continued. One morning about one o’clock an<br />

officer passing the Castle-alley from Whitechapel to Wentworth-street, paused under a lamp in the<br />

Alley to eat his supper. After eating his supper he walked down Castle-alley into Wentworth-street, a<br />

distance of less than a hundred yards. At the corner of Wentworth-street he met an officer coming in<br />

the reverse direction to pass over the same ground. They stood about a minute exchanging a word, and<br />

officer number two went up the alley. Number one had taken a few steps down Wentworth-street when<br />

he heard his mate’s alarm whistle. He ran back into Castle-alley and found his mate standing over the<br />

corpse of a woman who had been murdered and mutilated on the very spot where within the past five<br />

minutes he had stood.<br />

The alarm was continued. Other officers came upon the ground. A running search was made in every<br />

direction, but no sight or sound could be traced of the murderer, who had evidently not quite completed<br />

his work when the arrival of officer number two had disturbed him. Immediately above the spot where<br />

the body was found was the window of a room in which the keeper of some wash houses slept, and there<br />

was a light in his window. The keeper was roused. His wife came down to the door and said, ‘I have not<br />

been asleep. I was sitting reading to my husband, and we have heard no sound.’ The murderer and his<br />

victim had evidently followed officer number one into the alley and hidden in one of the entries leading<br />

into it while he was eating his supper. Probably they watched him until he got down to Wentworthstreet.<br />

The method followed by the murderer was to first cut his victims’ throats from right to left in a quiet<br />

way which killed them before they could make a sound, and which caused the blood to spurt out away<br />

from his hand and from his body. This is the secret doubtless of the left-hand theory, and it is most<br />

probable that the murderer never had a speck of blood upon his clothes. The bodies, life having ceased,<br />

would not spurt blood during the mutilation.<br />

The last murder displaying the same hand of the homicidal maniac, happened two years later in<br />

Swallow-gardens. The name belies the place, which is a very dark, dismal railway arch through which<br />

persons may pass from one street to another. The spot is one into which very few people ever dare to<br />

enter after midnight. A young constable, a Cornwall man, who had been a miner, and who had been in<br />

the force only six weeks, was on duty near the place, and hearing footsteps retreating rapidly as he<br />

entered the archway he ran forward in the direction of the sound. He stumbled over something lying<br />

on the ground, and on turning his light on to it found a woman with her throat cut and bleeding. Her<br />

eyes and lips were moving. The woman was just expiring. The policeman’s arrival at the entrance to the<br />

archway had disturbed the Ripper but a moment too late. However, he darted forward in the direction<br />

of the running footsteps, still to be heard. It was so dark he could see nothing. Yet he continued to run<br />

on, and was gaining on the sound when the pursued steps suddenly became silent.<br />

The officer turned on his light and searched in every possible direction round the spot where the<br />

footsteps had ceased, but he could find no one. For this murder a man was arrested, but he succeeded<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 5

in completely proving his innocence. That was the last Ripper murder.’<br />

And now tell me a few things. First, how do you account for the man so skilfully escaping you all?<br />

‘As I have explained, we never in one single instance found a person who had seen a man with any of<br />

the murdered women on the evenings they were murdered, so we never had a description of him. This<br />

is accounted for by the fact that every victim was a woman of ill-fame of the very lowest type, and that<br />

in every instance the woman took the man secretly, at a moment when no one was in sight, away to a<br />

quiet, hidden, secluded spot known by her, never frequented at night-time. Further, with the exception<br />

of the last two cases, the place of the murder was on private property; that is, in a place into which the<br />

law forbids that a policeman should enter. The victims themselves selected the hiding-place, the scene<br />

of their murder, and sought it in a stealthy manner which prevented them being seen. They selected<br />

their murderer, they selected the scene of their death, and provided their assailant with escape. They<br />

took care to render impossible evidence of their being seen taking a man to the scene of the murder.’<br />

And what is your own idea of the murderer?<br />

‘That he was a homicidal maniac there was no doubt, and had that cunning of insanity which defies the<br />

reason of sane persons is equally certain. I am satisfied that he was a man who did not seek victims. My<br />

notion is that he might never have committed a murder at all had he not been solicited and led away<br />

by the women; but that on every occasion when this happened to him the frenzy came upon him. His<br />

carrying a knife may be accounted for in dozens of ways. It is likely, too, that in every instance drink had<br />

much to do with the recurring mania. Every one of the murders was committed after the public-houses<br />

closed at night, most of them within an hour afterwards.’<br />

Have you the remotest idea who or what the man was?<br />

‘He was a vulgar man; that is, he was no scientist or medical man – not even a butcher – I should say,<br />

from the same clumsiness displayed in his frenzied work in each case. I have always believed that he<br />

lived somewhere in the neighbourhood of Berner-street. The first of the murders was in that district,<br />

and every one was committed within a radius of a quarter of a mile of the Princess Alice public house in<br />

Commercial-street. All of the women lived in that district, and so I believe did the murderer. There are<br />

similar women, and equally hidden spots in other parts of London, yet no Ripper murder was committed<br />

in any other part of London. Then, again, on the night of the Berner-street murder he went down Citywards,<br />

when he murdered the woman in Mitre-square and returned to Berner-street within an hour and<br />

a half, to the spot where the piece of the Mitre-square woman’s apron was found, thrown on the ground<br />

beneath the writing on the wall.’<br />

Now, what became of him?<br />

‘I believe he is dead. You see every case disclosed that with each recurring attack of the mania the fury<br />

of the frenzy was intensified. The greatest probability is that the effect on the murderer’s system was<br />

physical exhaustion of a kind which would destroy the system. Yes, I should say Jack the Ripper is dead.<br />

Most likely he died in a madhouse.’<br />

Among other things which <strong>Reid</strong> spoke of was the fact that though called Whitechapel murders, most of<br />

them were committed in Stepney and Spitalfields. He also said it was a mistake to fancy the murders<br />

made the Ripper feared by the class of people who alone had need to fear him.<br />

‘I have heard wretched women of that class, starving, homeless, unhappy creatures in the misery of<br />

their debased life, scream for Jack the Ripper, pray for him to come to them and end their misery. And<br />

I saw children in the street, when the scare was at its height, laughing and skipping, and enjoying life,<br />

playing at the game of the Ripper.’<br />

The journalist ended the interview by informing readers that:<br />

<strong>Edmund</strong> <strong>Reid</strong>, by the way, is still one of the most popular men in the East End, and an influential<br />

committee has been formed, of which Mr Solomon, of 18 Commercial-street, is the secretary, for the<br />

purpose of presenting him with a handsome testimonial from Whitechapel tradesmen, as a memento of<br />

his services among them. 2<br />

2 News of the World, 12 April 1896.<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 6

As in other interviews given by <strong>Reid</strong> on the Whitechapel murders, this<br />

contains glaring and obvious errors, including getting the year of the Mitre<br />

Square murder wrong, saying that Emma Smith was killed by one man when<br />

she had described three attackers, claiming that no body parts had been<br />

removed and saying that nobody saw a man with any of the victims on the<br />

nights they were killed are just a few examples.<br />

from Lloyd’s Weekly News<br />

<strong>Reid</strong> repeated his belief that there were nine murders, that the murderer<br />

had no anatomical knowledge and was a homicidal maniac who was probably<br />

dead by 1896. He elaborates on his theory that the victims were largely<br />

responsible for their own deaths with the curious suggestion that Jack the<br />

Ripper had not been seeking victims and might not have killed anyone if<br />

he not been given the opportunity to do so and escape undetected. It is<br />

difficult to believe <strong>Reid</strong>’s story about John McCarthy’s mental breakdown,<br />

as immediately after the murder of Mary Kelly he was lucid enough to be<br />

interviewed by the Sunday Times newspaper and to give evidence at Kelly’s<br />

inquest a few days later.<br />

It is perplexing to read the remarks of a police officer who had worked so closely on the Whitechapel murders<br />

investigation for so long, making numerous errors just a few years after the crimes had been committed. Yet<br />

on other occasions <strong>Reid</strong> was accurate, such as still being able to remember exactly how much weekly rent Mary<br />

Kelly had to pay. Disappointingly, <strong>Edmund</strong> <strong>Reid</strong> has not proved to be the most reliable source on the subject of<br />

the Whitechapel murders. However, his ultimate conclusion that the identity of Jack the Ripper was not known<br />

is entirely reasonable.<br />

In 1902 <strong>Reid</strong> took umbrage when the Metropolitan Police offered retired officers a modest sum to assist at the<br />

Coronation of King Edward VII in London. <strong>Reid</strong> felt that it was rather insulting for retired sergeants and inspectors<br />

to receive ‘the same as a pensioned third-class constable. It is not a matter of sight-seeing with them, but hard<br />

work, many leaving a home and business for a time, travelling many miles; and, another thing, no matter how<br />

loyal one may be, he does not want to be out of pocket in the manner.’ 3<br />

<strong>Reid</strong> later added:<br />

I do not wish to egotise, but should like to say that I was a detective-inspector twelve years, both at<br />

the Yard and Whitechapel during the Ripper murders, and only left in 1896, and now am asked to offer<br />

myself for duty during the Coronation at the same price as a constable who has just managed to get a<br />

small pension with the skin of his teeth.<br />

I certainly think that some distinction should be made according to rank, and that all should be asked<br />

to assist. I do not intend to offer myself after the disrespect shown to an officer who also left with a<br />

good character. 4<br />

Despite this disagreement with his former employers it seems that <strong>Reid</strong> was still willing to do them a good<br />

turn. In 1912 and 1913 he advertised his services, free of charge, to advise young men who wished to join the<br />

Metropolitan Police Force. 5<br />

By the time of the Coronation <strong>Reid</strong> had left London for his native east Kent and in the early 20th century was<br />

registered as living at ‘<strong>Reid</strong>’s Ranch’ in Hampton-on-Sea, a tiny seaside hamlet of Herne Bay. He was simultaneously<br />

living at a house in Borstal Hill in the neighbouring town of Whitstable. There he joined the quoit club 6 and<br />

wrote letters to the local newspaper. In 1905 a Whitstable resident, writing under the name of ‘A Progressive’,<br />

complained in a letter to the Whitstable Times about the state of the town which ‘excels in untidiness. Many<br />

of the roads are overgrown with weeds and the water channels at the side of the roads are full with grit and<br />

manure.’ The seafront was in a ‘deplorable’ condition, and worst of all, a refuge dump had been established at<br />

the eastern entrance of the town, close to the main road. 7<br />

3 Daily Mail, 29 April 1902.<br />

4 Daily Mail, 12 May 1902.<br />

5 Whitstable Times, 14 & 28 December 1912; 4 January 1913.<br />

6 Whitstable Times, 14 October 1905.<br />

7 Whitstable Times, 15 July 1905.<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 7

<strong>Reid</strong> was unsympathetic and wrote to the paper in characteristic style:<br />

Why, what ever is the matter with the anonymous writer who signs himself ‘A Progressive’ in your last<br />

week’s issue touching the above subject [‘Progressive Whitstable’].<br />

Why don’t he come and live up Borstal Hill way, where all is peace and joy? We ain’t got no troubles up<br />

our way like he writes about.<br />

We ain’t got no path to get out of order between ‘The Four Horse Shoes’ Hotel and the end of Whitstable<br />

District.<br />

We ain’t got no gas lamp that wants lighting to show us our way home on a dark night like they have at<br />

Tankerton.<br />

We ain’t got no scavengers coming and taking away our dust and putting it in a heap to annoy our<br />

visitors. We look after that ourselves.<br />

We ain’t got no trouble to<br />

read any acknowledgement<br />

to our applications for a<br />

gas lamp and a path to the<br />

end of Whitstable District<br />

(which we pay for), because<br />

they never send one.<br />

Cheer up, old boy, better<br />

days in store.<br />

Thanking you in anticipation<br />

for a good time coming,<br />

when we shall all know the<br />

boundary of Whitstable on<br />

the road to Canterbury by<br />

the erection of a gas lamp<br />

on a footpath. 8<br />

His practice of writing letters<br />

Postcard showing Whitstable from Borstal Hill, where <strong>Reid</strong> made his home<br />

to the press continued and, as in<br />

Herne Bay, a local councillor was<br />

the target of his chagrin. Councillor Church had remarked that he did not think that the gas company should be<br />

asked to extend their mains into the country. In response to this <strong>Reid</strong> wrote a long letter to the Whitstable Times<br />

which they declined to publish as it was ‘of too personal a character to be inserted in its entirety.’ 9 The gist of the<br />

letter was that <strong>Reid</strong> could not understand ‘how Councillor Church can show so much ignorance as not to know the<br />

extent of the district, adding that the boundary of the Urban District extends to just past the ‘Long Reach’ Tavern,<br />

and that there are several persons residing in the Councillor’s so-called country who would be only too pleased to<br />

burn gas in their houses if they got the chance.’ 10<br />

<strong>Reid</strong> had taken out a six-year lease of the unfurnished Borstal Hill house early in 1905, but in 1907 he was sued<br />

by his landlord, George Hall, for non-payment of a quarter’s rent of £5 10s, plus 5s in interest on the payment.<br />

<strong>Reid</strong> had always settled regularly up until that time, but now he claimed he was unable to pay and offered Hall an<br />

extra pound a year in rent if he could just wait a while longer for the quarterly payment. Hall was not interested<br />

and the case ended up at the Canterbury County Court in April 1907.<br />

Unfazed at being a defendant in a court case, <strong>Reid</strong> argued that the house was unfit to live in. He claimed that<br />

it was overrun with rats and that there was ‘not a room that the rain does not come in.’ George Hall was not<br />

impressed by his truculent tenant’s defence. He told <strong>Reid</strong> that he had ‘got it cheap enough’ at £22 a year and<br />

if there were any rats in the property it was through his own neglect. The judge pointed out that the alleged<br />

condition of the house was not a valid defence as <strong>Reid</strong> had already lived there for two years and was only now<br />

8 Whitstable Times, 22 July 1905.<br />

9 Whitstable Times, 21 July 1906.<br />

10 Ibid.<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 8

<strong>Edmund</strong> <strong>Reid</strong> at Hampton-on-Sea<br />

making an issue of it. Furthermore, the tenancy agreement <strong>Reid</strong> had signed placed him under obligation to keep<br />

the house in a good state of repair. <strong>Reid</strong> countered this by asking why, if that was the case, Hall had paid for<br />

previous repairs to the house. The judge said this was irrelevant and even ‘if the roof fell in about your ears it<br />

would be no defence in law.’ <strong>Reid</strong> retorted that ‘It has been down twice and he has put it up again.’<br />

By now Hall’s patience had run out. He told <strong>Reid</strong> that he had another potential tenant who would take the<br />

house immediately, ‘but I won’t release you Mr <strong>Reid</strong>. Oh no!’ <strong>Reid</strong> replied ‘It is a hornet’s nest about my ears.’<br />

Hall seemed to relent and said ‘If you will compensate me I could let it tomorrow.’ The judge’s ruling was that<br />

<strong>Reid</strong> had to pay the outstanding £5 10s by the end of May, but not the 5s interest. Hall’s lawyer pointed out that by<br />

then another quarterly payment would be due, to which Hall said ‘And I will have him for it.’ Playing to the court,<br />

<strong>Reid</strong> glibly replied ‘You will have your pound of flesh.’ This raised a laugh, but Hall was unamused, responding<br />

‘Yes, I will.’ 11<br />

This episode shows <strong>Reid</strong> in a poor light. He had failed to pay his rent for a house which the landlord had<br />

maintained, despite it being <strong>Reid</strong>’s responsibility. Hall’s anger towards <strong>Reid</strong> is understandable and it is to his<br />

credit that he stood up to <strong>Reid</strong>, who he knew was a former Scotland Yard inspector as well as something of a<br />

local celebrity. And why was <strong>Reid</strong> keeping two houses at once? In 1912 and 1913 when offering to help potential<br />

Metropolitan Police recruits he again had an address in Whitstable while still living at ‘<strong>Reid</strong>’s Ranch.’ On that<br />

occasion it was 84 High Street.<br />

<strong>Reid</strong> owned the ‘Ranch’ at Hampton and when it was inspected for the 1910 Finance Act survey it was noted<br />

that: ‘The house is in a very dilaptd [sic – dilapidated] Condition’, and that the sea was rapidly encroaching. 12 It is<br />

not clear if this indicates that the interior of the house was dilapidated or if coastal erosion had started to attack<br />

the foundations and exterior of the ‘Ranch’. A number of properties in Hampton were lost to coastal erosion<br />

around 1910, although <strong>Reid</strong> did not leave the Ranch until 1916. An earlier visitor to the ‘Ranch’ said it was ‘a well<br />

arranged cottage.’ 13<br />

11 Whitstable Times, 13 April 1907.<br />

12 TNA, PRO IR58/17510.<br />

13 Herne Bay Press, 27 September 1902.<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 9

In 1913 <strong>Reid</strong> wrote a series of articles on his ballooning exploits which had been hinted at in articles and his<br />

obituaries. They were written years after the events by <strong>Reid</strong>, so it remains to be seen how much of it is accurate<br />

and how much is <strong>Reid</strong> being a raconteur. His first balloon ascent came about after he made the acquaintance of<br />

the self-styled ‘Professor’ Thomas Lythgoe, an experienced aeronaut. 14 One evening he was chatting to Lythgoe<br />

over a pipe when he was asked ‘Ever been down in a diving bell?’ <strong>Reid</strong> replied that he had. Lythgoe then wondered<br />

if <strong>Reid</strong> had ever been up in a balloon. <strong>Reid</strong> had not, so Lythgoe offered to ‘arrange for a trip from the Crystal<br />

Palace.’ At a subsequent meeting on a Tuesday evening, Lythgoe told <strong>Reid</strong> to meet him at the Crystal Palace<br />

on Saturday at three o’clock in the afternoon when they would make an ascent with another balloonist named<br />

Thomas Wright. <strong>Reid</strong> told nobody about his forthcoming adventure and spent the rest of the week wondering if he<br />

would be alive the following week.<br />

Dark clouds began to appear shortly before the balloon was due to take off, so the three intrepid men got into<br />

the balloon car and took off before the rain made their balloon wet and heavy. <strong>Reid</strong> remembered:<br />

The world seemed to drop down from us. I felt no motion at all. It was not long before a dark cloud<br />

came all around us, then the cloud went down, and we were in the light again with the blue sky over our<br />

heads. But all at once there was a flash of lightning and a clap of thunder, and I began to think. I said<br />

to Mr Lythgoe ‘What’s that?’ He replied ‘Oh, that’s nothing.’ I said ‘You call that nothing.’ He replied<br />

‘Let the lightning flash and the thunder roar, it won’t hurt us as we are not attached to the earth.’ And<br />

it didn’t, or I should not be writing this now.<br />

A balloon ascent from the Crystal Palace. From Travels in the Air by James Glaisher (1871)<br />

<strong>Reid</strong> had been seated in the car<br />

and when he stood up he saw the<br />

dark storm clouds beneath him and<br />

a clear blue sky above. It was ‘one<br />

of the grandest panoramic views<br />

that I have ever seen.’ The Crystal<br />

Palace looked like ‘a little glass<br />

house standing on a carpet,’ while<br />

the River Thames resembled a<br />

narrow ditch. All pre-flight nerves<br />

disappeared as <strong>Reid</strong> marvelled at<br />

the splendour of the view and he<br />

felt completely safe and calm.<br />

The balloon was nearly two miles<br />

high and <strong>Reid</strong> was now thoroughly<br />

enjoying himself. The dizzying<br />

heights were ‘a nice place to live<br />

in, no tax collectors, nothing to<br />

upset the mind.’<br />

They were now floating over Gravesend. <strong>Reid</strong> mused:<br />

Why it looks to me like a lot of red bricks thrown into a field. Then I began to think – there are<br />

thousands of houses down there, and thousands and thousands of people, some walk about as if the<br />

world belong to them only; some that will sometimes condescend to speak to you under circumstances<br />

to suit themselves only; others that work hard to live, yet I cannot see one, then what am I when I am<br />

down there, nothing, not so much as a grain of sand. I think that if there is anything to take the pride<br />

out of anyone it is being up in a balloon. It teaches that the world can go on very well without us, and<br />

perhaps better, and whenever anyone tells you all about what is up here, that has never been, well to<br />

put it in a mild form, you can look at them and think. I have never heard the angels sing yet, and I have<br />

made many balloon ascents in my time. 15<br />

14 Thomas Lythgoe worked as a meter inspector to the Metropolitan Gas Company, retiring in 1885 to become landlord of the Duke<br />

Inn at St Albans. He later took over the Old Oak Inn in Hertford where he died in 1893 aged 61. He made 405 ascents over 43 years.<br />

(Hertfordshire Mercury, 1 April 1893). <strong>Reid</strong>’s memory was working reasonably well on this matter some twenty years later. He<br />

wrote that ‘After he [Lythgoe] gave up ballooning he kept ‘The Old Oak Hotel’ at Hertford, where he died a natural death.’<br />

However, <strong>Reid</strong> asserted that Lythgoe had made over 500 ascents. (Whitstable Times, 11 January 1913).<br />

15 Whitstable Times, 11 January 1913.<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 10

This sounds similar to Yuri Gagarin’s alleged quote, ‘I see no god up here’, made during his pioneering 1961<br />

space flight. It is purely speculation, but could this have been the origin of <strong>Reid</strong>’s agnosticism? Having ascended<br />

to the heavens and finding nothing there, did <strong>Reid</strong> abandon any idea of a Biblical Heaven, or did he have doubts<br />

before then? He had been baptised at St Alphege Church in Canterbury city centre on 4th October 1846, but it is<br />

not clear how seriously he took religion in his youth.<br />

Lythgoe spotted a likely landing site by the railway station and the balloon descended at Shorne in Kent. <strong>Reid</strong><br />

‘saw the green grass grow into a wood, houses come up through the earth; people popped up out of holes, and<br />

the earth came up and hit the bottom of the car… when the gas was all gone out of the balloon we all got out,<br />

and then I said to myself ‘I have done it.’’ 16<br />

They packed the deflated balloon into the empty car, loaded it onto a cart and went to the nearest pub for tea.<br />

On the train back to London Bridge, <strong>Reid</strong> reflected on how much he had enjoyed the experience and thought that<br />

‘if I had been blindfolded in the car, I should not have known that the balloon had started as I felt no motion.’ 17<br />

<strong>Reid</strong> later wrote of another ascent he made from the Crystal Palace. He decided to amuse the crowds of<br />

children who were in attendance:<br />

I obtained a long piece of string and attached one end to the balloon car and laid the rest over the side<br />

so that it should not be entangled, then I made a small hole in the brim of my straw hat, and when<br />

everything was ready I tied the other end of the string to my hat and put it on my head, let go the<br />

liberating iron, when down went the world with the people in it, and as they were going down, I took<br />

off my hat and shouted ‘Hurrah,’ swinging my hat round and round, then let it drop down.<br />

I heard a general shout of laughter and cries ‘He’s lost his hat.’ When the hat had reached the length of<br />

the string I pulled the hat up and swinging it round again shouted ‘Hurrah,’ and I could hear the people<br />

laughing again at the fun of the thing. 18<br />

As <strong>Reid</strong> drifted over Chislehurst he shouted down to the residents, ‘You have got the grandest garden that I<br />

have ever passed over.’ <strong>Reid</strong> explained that by speaking loudly and distinctly it was possible to communicate with<br />

people on the ground from up to half a mile high. Over Hayes Common, <strong>Reid</strong> performed his hat trick again for a<br />

group of school children, then passed over some fields where he dropped a bottle of water over the side of the<br />

car, seeing it vaporise into a cloud of dust when it hit the ground.<br />

He later dropped some ballast on a strawberry picker who had responded to <strong>Reid</strong>’s request for some strawberries<br />

by saying, ‘Come down and break your neck.’ <strong>Reid</strong> eventually landed in a field in Westerham and bought drinks<br />

for the locals who had helped him pack up his balloon. As they entered the Pig and Whistle pub one of the helpers<br />

called out: ‘See what I have brought you, a gentleman from the clouds.’ 19<br />

<strong>Reid</strong> made another ascent from the Crystal Palace at a police fete with two friends. He had secretly obtained<br />

two bullocks bladders which he filled with gas and sealed with wax before fastening them with two pieces of<br />

string beneath the balloon car. As they took off <strong>Reid</strong> looked down and saw ‘about seven thousand policemen, their<br />

wives and sweethearts (or someone else’s).’ One of <strong>Reid</strong>’s friends had bought two pigeons, the first of which was<br />

released when the balloon was about half a mile high and the other at a quarter of a mile above that. They both<br />

fell some way before they were able to open their wings and safely fly off.<br />

Shortly afterwards, the bullocks bladders exploded:<br />

All of a sudden there was a loud report as of a cannon being fired off, when both my friends called<br />

out ‘What’s that: what’s the matter?’ I replied ‘Oh, it’s all right,’ when bang went another, somewhat<br />

louder than the first. That did it. They both looked as if they had been eating Whitstable oysters that<br />

had been crossed in love.<br />

I afterwards explained to them that it was only the two bladders burst owing to the expansion of the<br />

gas, the same as the balloon would burst if the mouth was not left open to allow the expanded gas to<br />

escape.<br />

16 Whitstable Times, 11 January 1913.<br />

17 Ibid.<br />

18 Whitstable Times, 25 January 1913.<br />

19 Ibid.<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 11

From Travels in the Air by James Glaisher (1871)<br />

We put the matter right by having a sip of that which cheers the heart and gives us courage, and drunk<br />

to the health of those we left behind, and when we looked over the side of the car we found that we<br />

were passing over Forest Hill cemetery, a very healthy place to be buried. 20<br />

The wind dropped and it took the balloon over half an hour to float across the River Thames instead of the usual<br />

ten minutes, only for it to be blown back again and left stranded in mid-air as the boats below blew their whistles<br />

in greeting. The balloon eventually ended up over Barking in East London where it unceremoniously landed in an<br />

onion field and crowds of curious onlookers gathered around, trampling over the crops.<br />

<strong>Reid</strong> had a low opinion of Barking locals and felt that they had been watching the balloon as if it were ‘a ship at<br />

sea, watching to divide the spoil.’ He sent for the farm owner, only to be confronted by his bailiff who demanded<br />

£100 in compensation for the damage done to the fields by the mob. He had sent for the police and two officers<br />

arrived at the scene. <strong>Reid</strong> was unconcerned, arguing that the balloon itself had not caused any damage and had<br />

only landed there by accident. As this was going on, <strong>Reid</strong> and his friends were packing up the balloon as quickly<br />

as they could and his friends managed to leave the scene with the balloon as <strong>Reid</strong> was taken to Barking Police<br />

Station.<br />

Recognising the sergeant on duty, <strong>Reid</strong> explained that the ascent had been made for the benefit of the Police<br />

Orphanage and that the onion field was the only viable landing site, after having been stranded over the River<br />

Thames and three different cemeteries. The sergeant said that there could be no criminal charges against <strong>Reid</strong>,<br />

but suggested to the bailiff that he could take out a summons against him. The bailiff threatened to keep <strong>Reid</strong>’s<br />

balloon until he received the money, but <strong>Reid</strong> pointed out that the balloon had already been taken away, a fact<br />

that made the bailiff look like ‘he had been eating fried oranges that didn’t agree with him.’ <strong>Reid</strong> supplied<br />

his name and address to the bailiff should he wish to sue him and then threatened to counter-sue for false<br />

imprisonment, after which the bailiff left the station.<br />

<strong>Reid</strong> stayed to chat with the sergeant but was growing concerned about the mob that had gathered outside<br />

the police station who thought they were entitled to payment for helping the balloon down. Those that had<br />

20 Whitstable Times, 5 April 1913. It was said of <strong>Reid</strong> that he ‘never tasted intoxicants’ until he was 36 (Lloyd’s Weekly News, 4<br />

February 1912), so presumably this escapade occurred after 1882.<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 12

just touched to guide-rope expected to be paid a shilling each. Then an inspector entered the station, having<br />

coincidentally just returned from the Crystal Palace where he had seen <strong>Reid</strong> take off. They came up with a plan<br />

to help <strong>Reid</strong> escape unseen. A police officer went out and found a horse-drawn brake which was taken back to<br />

the station. <strong>Reid</strong> concealed himself under a seat and the brake drove off through the oblivious crowd. <strong>Reid</strong> was<br />

reunited with his friends at the South London Music Hall.<br />

Deciding to settle the claim out of court, <strong>Reid</strong> eventually paid the<br />

onion farmer £20, but thought that if it had gone to court he would<br />

have won, or been fined less than £20. One thing he was certain of<br />

though was that he never wanted to go to Barking again. 21<br />

As a young man <strong>Reid</strong> had an interest in parachuting and had once<br />

made a small parachute which he attached to a mouse’s tail with<br />

cotton threads. He then dropped the mouse from a high building.<br />

The parachute worked and the mouse scurried off with the parachute<br />

still attached to its tail. <strong>Reid</strong> had also seen a monkey and a cat<br />

making parachute descents at the music halls.<br />

Without giving any specific details of his own parachute jumps,<br />

<strong>Reid</strong> explained his method:<br />

Now let us suppose I am about to make a parachute descent.<br />

The first thing I do is to see that the balloon is ready with the<br />

bag of ballast at its side. I may here mention that on the top<br />

of the parachute is a wire hook, and that has to be hooked into<br />

a ring. I told you of inside the canvas tube at the side of the<br />

balloon, and having seen that that is all right, and that all the<br />

cords attached to the parachute are clear, and not in a tangle,<br />

then I attach my basket to my seat which is fastened to the<br />

ropes that hold the net over the balloon, in such a way that I<br />

can slip in and release myself when I want to. Then I take my<br />

place on my seat, hold the ropes, and cry ‘Let go,’ and the men<br />

standing round holding the balloon down, let go, and the world<br />

appears to drop away from me.<br />

When I begin to lose sight of the people on earth, I slip into my<br />

basket and leave the rest to do its work; my weight releases<br />

the basket from the seat, the hook in the ring becomes straight and comes out of the tube and the<br />

parachute opens like an umbrella.<br />

When the balloon is released of its weight the bag of ballast pulls the top down, and the mouth up, and<br />

lets the hot air out, and the question is which reaches the ground first, you or the balloon.<br />

That is my style of parachuting, with a basket to stand in. In the case of a balloon you may sometimes<br />

pick the place for coming down, but with the parachute you must come down where it likes to drop you.<br />

When you are up in a balloon, or dropping with a parachute, there you are, don’t you know, you may<br />

call yourself professor, captain, or some other grand name, it’s all the same, you have got to get down. 22<br />

This eccentric detective, daring balloonist and notable man of Kent, whether up in the air, or with his feet on<br />

terra firma, remains one of the most interesting and unusual individuals associated with the Whitechapel murders.<br />

21 Whitstable Times, 5 April 1913.<br />

22 Whitstable Times, 20 April 1913.<br />

NICHOLAS CONNELL is the co-author of The Man Who Hunted Jack the Ripper: <strong>Edmund</strong> <strong>Reid</strong>-Victorian Detective.<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 13

Brother Abberline and<br />

A Few Other Fellow Notable<br />

Freemasons<br />

By LINDSAY SIVITER<br />

Today the United Grand Lodge of England claims to have over a quarter of a million Freemasonic<br />

members. Worldwide there are approximately six million freemasons. 1 For many years, Ripperologists<br />

and indeed the wider public have been fascinated with the notion that the Freemasons were<br />

somehow involved in a conspiracy to conceal the truth about the identity of the perpetrator of the<br />

infamous Jack the Ripper murders. While this theory is very much currently in the news thanks to<br />

Bruce Robinson's They All Love Jack, much of it began back in 1976 with an intrigue convincingly<br />

weaved by the late Stephen Knight in his book, Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution. So powerful<br />

was the impact of this book that over the years several films have been heavily influenced by it,<br />

most notably Murder by Decree in 1978 and From Hell in 2001.<br />

However, before Knight's book was published, the premise had<br />

already been established in an episode of the six-part series Jack the<br />

Ripper in which two popular fictional TV detectives, Barlow and Watt,<br />

took a look at the Whitechapel murders through the eyes of two modern<br />

policemen. Towards the end of the series Joseph Sickert was seen briefly<br />

explaining an amazing tale. Joseph claimed the murders were done as<br />

a way of securing the silence of several women who had knowledge of<br />

Queen Victoria’s grandson, Prince Albert Victor, having secretly married<br />

a shop-girl called Annie Crook.<br />

The secret wedding had apparently been witnessed by Mary Jane<br />

Kelly, the final of the Ripper's canonical victims, who had to be silenced<br />

after she threatened blackmail. Annie Crook, according to the story,<br />

subsequently gave birth to a baby girl called Alice, whom Joseph Sickert<br />

claimed to be his mother.<br />

Knight later met Joseph, who supplied further details, and the<br />

impressive tale was subsequently expounded on throughout Knight's<br />

book. Whole sections argued that a masonic cover-up of the Ripper<br />

murder had occurred, with several high-ranking freemasons being<br />

involved including Sir William Gull, Lord Salisbury and Sir Charles<br />

Warren.<br />

Prince Albert Victor<br />

As part of his research for the book, Knight spoke to John Hamill,<br />

the Librarian at United Grand Lodge Library & Museum in Great Queen<br />

Street, London, who told him that in actual fact only the latter of the<br />

three men previously mentioned was a freemason. However, for some<br />

reason, Knight chose to ignore this information, publishing several<br />

erroneous statements in his book about how Gull, Salisbury and others<br />

were freemasons despite official evidence to the contrary.<br />

1 See www.ugle.org.uk for statistics.<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 14

Sir Charles Warren<br />

Over the years, there has been much speculation about those involved in the<br />

Ripper investigation and whether they were freemasons. Many of the characters<br />

involved were, their freemasonic histories being well publicised and freely<br />

acknowledged in their obituaries. The masonic careers of Sir Charles Warren<br />

(1840-1927), Prince Albert Victor (1842-1892) and Dr Thomas Horrocks Openshaw<br />

(1856-1929) are widely known. Indeed, Openshaw's vast and impressive collection<br />

of masonic medals have been on display for many years in the Royal London<br />

Hospital Museum as he was a founder of the London Hospital Lodge No. 2845,<br />

being initiated 14 March 1901. Openshaw was a member of several Masonic<br />

Lodges, including Hotspur Lodge No. 1626 (Initiated 1882), Old Concord Lodge No.<br />

172 (Initiated 1890), Lancastrian Lodge No. 2528 (Initiated 1894), The University<br />

of Durham Lodge No. 3030 (Initiated 1904), Foxhunters' Lodge No. 3094 (Initiated<br />

1908) and Robert Thorne Lodge No.3663 (Initiated 1913). 2<br />

At various times many researchers, including<br />

myself, have enquired at the United Grand Lodge Library & Museum about<br />

membership of some of those involved in the Ripper investigation. Thankfully,<br />

for all us historians, in November 2015 the United Grand Lodge of England finally<br />

released their Freemasonry Membership Registers after a huge digitisation project,<br />

and these are now searchable via ancestry.co.uk.<br />

These revealing records cover membership records in England 1751–1921 and<br />

Ireland 1733-1923, alongside various lodges in Commonwealth countries. There<br />

are now over two million records available, allowing us to explore and uncover<br />

membership details.<br />

Several times over the years I had enquired whether Sir William Gull had been<br />

a Freemason; the response was always negative, although the United Grand Lodge<br />

did say that not all their records had been properly indexed. I had always believed<br />

through my own research and meeting with his descendants that Gull had not been<br />

a Freemason, and a search in the new database confirms this. I can also confirm<br />

that neither was alleged Ripper coachman John Netley nor Prime Minister Lord<br />

Salisbury, proving Stephen Knight’s claims about these men were wrong.<br />

Det. Inspector Frederick George Abberline (1843-1929) was a Freemason,<br />

Dr Thomas Horrocks Openshaw<br />

however, and so was Sergeant George Godley (1857-1941), although they were not in the same lodge.<br />

Abberline was a member of Zetland Lodge, Lodge No. 511. The Register 3 entry showing Annual Dues paid from<br />

1888-98 informs us of the following:<br />

Date of Initiation: 1889 Dec 4th<br />

Passing: Feb 5 1890<br />

Raising: April 2 1890<br />

Surname: Abberline<br />

Christian Names: Frederick George<br />

Age: 46<br />

Residence: Scotland Yard<br />

Profession: Insp. Crim. Inv. Dept.<br />

Certificates: 11.4.90<br />

Abberline’s Date of Initiation in 1889 coincides with him finishing working on two of the biggest investigations<br />

in his career: the Whitechapel Murders (1888) and the Cleveland Street Scandal (1889). As a Candidate Abberline<br />

would have met most of the active members of his chosen Lodge before he was initiated, typically having been<br />

introduced by a friend within the Lodge, or at a Lodge open evening or social function. To become a Freemason,<br />

Abberline would have filled out a petition requesting that the Lodge admit him into its membership. After a<br />

2 Search results from Freemasonry Registers at www.ancestry.co.uk.<br />

3 Freemasonry Membership Registers via www.ancestry.co.uk.<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 15

Entry for Frederick Abberline and Arthur Hare (highlighted) in the Zetland Lodge register<br />

process of investigation and getting to know him, the Lodge would have voted to decide whether to accept his<br />

petition or not. Once the Lodge voted in favour then Abberline would have been then invited to the next meeting<br />

to receive his Entered Apprentice degree. This is where candidates are initiated into the Fraternity. 4<br />

The few membership records of Zetland Lodge that survive inform us that Abberline was listed (abbreviated)<br />

as an Inspector of the Criminal Investigation Department aged 46. He was initiated on the same day in 1889 as<br />

Mr Arthur Alfred Hare, a 34-year-old CID Inspector at Scotland Yard who had worked on the recent Thames Torso<br />

Murders and was probably good friends with Abberline. The two initiates would have done part of the rituals in<br />

the ceremony separately, and other parts would have been completed together.<br />

During the Ceremony of Initiation, the candidate is expected to swear (usually on a volume of a sacred text<br />

appropriate to their personal faith) to fulfil certain obligations as a mason. In the course of three Degrees, the<br />

new member promises to keep the secrets of their Degree from lower Degrees and outsiders. They also pledge to<br />

support a fellow mason in distress as far as the law permits. 5 The Degrees of Freemasonry retain the three grades<br />

of medieval craft guilds: those of Apprentice, Fellow (now called Fellow craft) and Master Mason. These three are<br />

what are known as Craft Freemasonry.<br />

The Masonic Lodge Freemasonry is an organisational unit of Freemasonry and it meets regularly to conduct<br />

formal business such as paying bills, organising charitable events and to elect new members. In addition to this<br />

formal business, meetings may be used to perform ceremonies to confer a masonic Degree or to present lectures<br />

on masonic history or rituals.<br />

Candidates are progressively initiated into freemasonry in the first Degree as an Entered Apprentice. They<br />

are then Passed into the second degree of Fellowcraft and are finally Raised to the Third Degree level of Master<br />

Mason. The registers tell us Abberline was Passed to the second Degree Freemasonry on 5 February 1890 and<br />

Raised to become a Master Mason on 2 April 1890. He progressed quite quickly through the three Degrees of Blue<br />

Lodge Freemasonry, as sometimes this can take many months to achieve.<br />

The column in the Registers saying the word Raised is as Mackey’s Encyclopaedia of Freemasonry explains:<br />

When a candidate has received the Third degree he is said to have been raised to the sublime Degree of<br />

Master mason. The expression refers materially to a portion of the ceremony of initiation, symbolically<br />

to the resurrection which it is the object of the Degree to exemplify… and also means the acceptance<br />

of the candidate officially by the fraternity. 6<br />

The Register also reveals that Abberline obtained his Certificates on 11 April 1890. This refers to a Grand Lodge<br />

certificate, which a member receives on completion of his three Degrees. Freemasonic certificates recognise<br />

a Master Mason’s special achievement of having been raised to the highest degree in Craft Freemasonry being<br />

rewarded in recognition of three main things.<br />

Firstly, your devotion to your Lodge, the Craft and the Brotherhood overall. Secondly, it represents your personal<br />

dedication and commitments to the principles which organise Freemasonry. Thirdly, it symbolises your continual<br />

journey in the quest for more (spiritual) light. 7 It is necessary for a mason to be certificated and the certificates<br />

themselves are regarded as a kind of Masonic passport to help gain admission to other Lodges.<br />

4 ‘What happens behind the scenes of a freemason’s initiation ceremony’ by Joel Montgomery, Master Mason on www.quora.com.<br />

5 www.wikipedia.org/freemasonry.<br />

6 Mackey’s Encyclopaedia of Freemasonry on www.masonicdictionary.com.<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 16

The register also tells us how much, and for which years Abberline paid his membership fees. These Dues, today<br />

as in Abberline’s time, cover the annual operating expenses of the Lodge. They are paid as an annual subscription<br />

after an initial Joining fee has also been paid. Throughout their careers, members also have to find money to pay<br />

for their Degree ceremonies which includes paying for materials received by the Candidate including regalia such<br />

as an Apron and study guides. Members are also expected to cover the cost of dinners and are encouraged to give<br />

to charity offering what they can afford. 8<br />

Abberline was a fully-paid member from 1889 right up until he resigned from his membership of Zetland Lodge<br />

in November 1903. His leaving the Lodge coincides with him retiring down to Bournemouth, where he lived for<br />

many years until his death in 1929. It is interesting to note that he did not continue his Freemasonic career after<br />

he moved and did not join any local Lodges in the Bournemouth area.<br />

Interestingly, alongside the above membership details from the Registers there is also<br />

a reference to Brother Abberline in The Freemasons Chronicle dated February 1891,<br />

which mentions him being present at the Covent Garden Lodge of Instruction No 1614. 9<br />

Covent Garden Lodge’s date of Warrant of Constitution was 1876, it being consecrated<br />

in 1877. From 1877 the Lodge met at Clunn’s Hotel in Covent Garden, but the following<br />

year they moved to Ashley’s Hotel nearby and by 1880 they met at The Criterion in<br />

Piccadilly, 10 which presumably was where Abberline went in 1891.<br />

Lodges of Instruction are where masonic learning takes place. These type of Lodges<br />

are often associated with a specific Lodge but are not constituted separately. These<br />

Lodges provide the Officers, and those who wish to become Officers, an opportunity to<br />

rehearse ritual under the guidance of a more experienced Brother.<br />

Lodges of Instruction are also places where lectures on symbolism and ritual are given<br />

to develop the knowledge of its members.<br />

Frederick George Abberline<br />

In an email to the library at Grand Lodge London, historian Zeb Micic asked for any<br />

information about Abberline’s membership of Covent Garden Lodge after having found<br />

the above same online reference to the Detective Inspector in a search of Freemasonic<br />

periodicals which are available on the UGLE Library website. 11<br />

Assistant Librarian Peter Aitkenhead replied saying that “Lodges of Instruction draw their members from many<br />

different lodges and it is impossible to identify the lodges whence they came unless their names appear in the<br />

membership lists of the lodge to which the Lodge of Instruction is ‘attached.” 12 Therefore, because there are<br />

no records maintained centrally of Lodges of Instruction, the librarian sadly could offer no further information.<br />

However, thanks to the new registers available we can establish Abberline’s main lodge being Zetland.<br />

Zetland Lodge had its Date of Warrant issued on 3 May 1845, and was consecrated officially as a new Lodge on 9<br />

July 1845. Members originally held their meetings at various pubs in the Kensington area, but from 1868 onwards<br />

the lodge met at Anderton’s Hotel 13 at 160 Fleet Street, which is where Abberline would have gone. Although<br />

there was a pub present on that site since medieval times, the establishment only became known as Anderton’s<br />

in the 1820s. The building was rebuilt in 1880 and a design for the new building by architects Ford & Hesketh can<br />

be seen in an illustration from The Building News dated 12 December 1879. 14 With its red brick and stone facade<br />

and Dutch-style gabled roof elements, it must have been quite striking. It was largely demolished in 1939 after<br />

several buildings were built on the site, which today is now occupied by a branch of HSBC. Throughout the time<br />

when Abberline visited, the Post Office Directory tells us the landlord was a Francis H Clemow. 15<br />

7 www.masonic-lodge-of-education.com.<br />

8 Ibid.<br />

9 Freemasons Chronicle, February, 1891, p.9.<br />

10 See Lane’s Masonic Records: The Library & Museum of Freemasons website (www.hrionline.ac.uk/lane/record).<br />

11 Correspondence between Zeb Micic and Peter Aitkenhead dated 29 April 2015.<br />

12 Ibid.<br />

13 Lane’s Masonic Records: The Library & Museum of Freemasons website (www.hrionline.ac.uk/lane/record)..<br />

14 Article containing information on the building’s history can be seen on www.archiseek.com as well as an illustration from The<br />

Building News, 12 December 1879.<br />

15 ‘Andertons Hotel’ by Stephen Harris on www.pubshistory.com.<br />

Ripperologist 147 December 2015 17

In Abberline’s time, meetings took place several times a year and were held on Wednesdays at Anderton’s<br />

Hotel. Anderton’s Hotel was by coincidence also the location where Doric Lodge No 933 used to meet whose<br />

membership included George Lusk, recipient of the famous 'From Hell’ letter. Lusk, listed as a ‘Builder’, was<br />

initiated on 14 February 1882, aged 41, and became a Master Mason a few weeks later on 11 April 1882. (I hope<br />

to publish an exclusive article for Ripperologist on George Lusk in 2016, as I recently met his descendants and<br />

obtained a lot of new information on him including photos of him and his family!).<br />

Today, Zetland Lodge meets at Freemason’s Hall, Great Queen Street and I made contact with a current<br />