You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

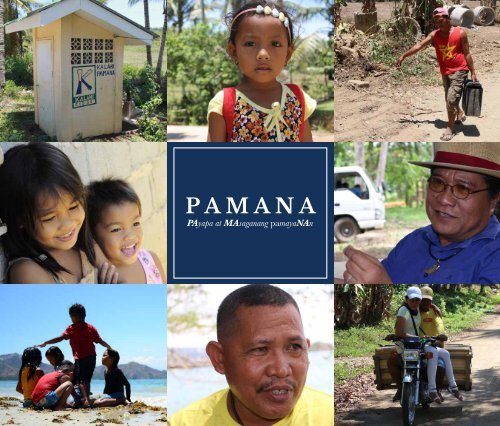

P A M A N A<br />

PAyapa at MAsaganang pamayaNAn

PAyapa at MAsaganang PamayaNAn or<br />

<strong>PAMANA</strong> is the national government’s<br />

convergence program that extends<br />

development interventions to isolated,<br />

hard-to-reach and conflict-affected<br />

communities, ensuring that they are not<br />

left behind.<br />

A complementary track to peace<br />

negotiations, the program is anchored<br />

on the Aquino administration’s strategy<br />

of winning the peace by forging strategic<br />

partnerships with national agencies<br />

in promoting convergent delivery of<br />

goods and services, and addressing<br />

regional development challenges in<br />

conflict-affected and vulnerable areas<br />

(CAAs/CVAs). The design and delivery<br />

of <strong>PAMANA</strong> is conflict-sensitive and<br />

peace-promoting (CSPP) to avoid the<br />

recurrence of any source of conflict.<br />

www.pamana.net

P A M A N A<br />

PAyapa at MAsaganang pamayaNAn

Editor’s<br />

Note

<strong>Table</strong> of<br />

Contents

6

INTRODUCTION<br />

What is <strong>PAMANA</strong>?<br />

PAyapa at MAsaganang PamayaNAn or <strong>PAMANA</strong> is the national government’s convergence program that extends<br />

development interventions to isolated, hard-to-reach and conflict-affected communities, ensuring that they are<br />

not left behind.<br />

A complementary track to peace negotiations, the program is anchored on the Aquino administration’s strategy<br />

of winning the peace by forging strategic partnerships with national agencies in promoting convergent delivery<br />

of goods and services, and addressing regional development challenges in conflict-affected and vulnerable areas<br />

(CAAs/CVAs). The design and delivery of <strong>PAMANA</strong> is conflict-sensitive and peace-promoting (CSPP) to avoid the<br />

recurrence of any source of conflict.<br />

What are the strategic pillars of <strong>PAMANA</strong>?<br />

<strong>PAMANA</strong> aims to extend development interventions to isolated, hard-to-reach, conflict-affected communities to<br />

ensure that they are not left behind. With a number of national line agencies as implementing partners, <strong>PAMANA</strong><br />

remains as the government’s flagship program for conflict-vulnerable and –affected areas in the country—covering<br />

all existing peace tables and agreements.<br />

7

MESSAGE FROM PARTNERS<br />

Ga. Et autOtatus. Rovit, si di dolo eos ipis aute nos estiberum re et alibus. Natis conecustet apiciat liquas dusant<br />

endandu ciundendia volo occatat quaerionet, saeped maionsequam, ulpa sum quos autem idelique eos res<br />

consequas parum, core porro et dolupta numqui quodica tiatus sandi doluptatio oditia dollorporio. Pa eaquis ne<br />

od ullaborit labor aut eat laut quidicium volorro vollia que resequo bla sunt ipis magnat. Upta niscid qui rerum<br />

susae. Ihillan digniet delluptatem que vent et laut ressusamus. Ehendae pudanisinum qui conempostin ra pratum<br />

voloriberum ra debita consequia doloribus auditium eic tem lam fuga. Bis nihicil loreperrum d.<br />

Ga. Et autOtatus. Rovit, si di dolo eos ipis aute nos estiberum re et alibus. Natis conecustet apiciat liquas dusant<br />

endandu ciundendia volo occatat quaerionet, saeped maionsequam, ulpa sum quos autem idelique eos res<br />

consequas parum, core porro et dolupta numqui quodica tiatus sandi doluptatio oditia dollorporio. Pa eaquis ne<br />

od ullaborit labor aut eat laut quidicium volorro vollia que resequo bla sunt ipis magnat. Upta niscid qui rerum<br />

susae. Ihillan digniet delluptatem que vent et laut ressusamus. Ehendae pudanisinum qui conempostin ra pratum<br />

voloriberum ra debita consequia doloribus auditium eic tem lam fuga. Bis nihicil loreperrum d.<br />

Ad expernatur as essit que venissus nossit ut molore non et auda vel is enit es reperum abo. Explaudi dendus<br />

arume autem hiliqui adi volorestius. Unt debit que res vitinve nistruntia nim volore plit, consequos eos et as aspere<br />

voluptat parunto tem faceror ectemolupid modi nobitibuscia que quassint od minveligent as et litae natem resectae<br />

nest, ommodit a solorro rrorpore porum faccabo rerchiciunto eatia quias reption nosa volorectur? Aximusdant<br />

quid moloriatet fugit, int errum quiae voloreri venda debis doluptati sam vercide moloreh entiatusam sed mint<br />

hita que rent voluptas expel esedis dolupta erumqui ute conse natur, omnissedit, ute ventinv elendus eos peritiam<br />

veni nobis ulpariant a volor andiosam, imus et, comnis moluptae quundi blatiunt vellam doles et offictibus vit ium<br />

ea qui inus es exceris soluptatem et fuga. Litatur? Everibus dolupis dolorios es duntio consed quid expelec uptation<br />

eium fuga. Cullab is maxim fugiam, corepedio volores simus, custrumet volutati quodis et quide anihit volorro<br />

rerchicae laut venihil moluptamus excere consequatur asim enis et quas arum nus ex etur, suntota quiae imolor<br />

aliatur? Qui utam ex evendit ditaerferum hiciis est, aute ne non corpore cepudiatur sed quam as ma conet lam,<br />

exerovid quaspedipic torernatiae ate cusandis dolut que nobist, si aceptia porro magnat.<br />

Ga. Et autOtatus. Rovit, si di dolo eos ipis aute nos estiberum re et alibus. Natis conecustet apiciat liquas dusant<br />

endandu ciundendia volo occatat quaerionet, saeped maionsequam, ulpa sum quos autem idelique eos res<br />

consequas parum, core porro et dolupta numqui quodica tiatus sandi doluptatio oditia dollorporio.<br />

8

9

10

P A M A N A<br />

STORIES<br />

11

12

CORDILLERA<br />

ADMINISTRATIVE<br />

REGION<br />

13

14

15

16

BICOL-QUEZON<br />

-MINDORO<br />

17

18

The<br />

Bridge that<br />

Occassionally<br />

Falls<br />

MOBO, MASBATE<br />

19

<strong>PAMANA</strong> STORIES<br />

THE BRIDGE THAT<br />

OCCASSIONALLY FALLS<br />

In 2007, Abello Frias nearly lost his life while crossing a dilapidated wooden bridge. He was on his way home<br />

with his wife and two kids when the multicab they were in almost fell into a cliff that could have compromised<br />

the family’s lives.<br />

“Kasi po noong tumagilid ang tulay, bumaba kami lahat. Nu’ng nadulas yung multicab, bumaba kami lahat.<br />

Pero ‘tinulak po namin yung multicab para pati yung driver makaligtas. ”<br />

Unfortunately, Abello’s experience was not an isolated case. This traumatic event also happened to some of<br />

his neighbors.<br />

Abello blamed it on their make-shift bridge -- made of weak coco lumber, and deteriorating due to changing<br />

weather. He knew that it has to be replaced for the sake of the communities in danger.<br />

“Apat po kaming barangay ang nagagalit sa gobyerno noong wala pang tulay (na maayos). Ang buhay namin<br />

nakataya diyan.”<br />

The four (4) barangays that depended on the bridge were Barangays Natunduan, Brgy. Lunungkatungdan,<br />

Brgy. Pabrika, and Brgy Dacu where Abello resides.<br />

Due to the frail state of the bridge, the residents could not transport heavy materials meant for building<br />

concrete houses.<br />

Even if they did get past the bridge, they still had to wade through the mud and flood that obstruct their way<br />

due to high tide.<br />

“Noong araw di ako naniniwala sa trabaho ng gobyerno, tapos ngayon biglang na-twist,” according to Abello.<br />

With the help of <strong>PAMANA</strong> and KALAHI-CIDDS, Barangay Dacu was able to build a concrete bridge and an<br />

elevated pathway, and Abello was the Chairman Volunteer tasked to monitor the said projects.<br />

“Ako mismo, nakapag-konkreto na ng bahay. Dahil po ang materyales na ino-order namin sa Masbate,<br />

nakaka-raan na po sa tulay.”<br />

The infrastructure projects made Abello’s barangay, and the three other barangays, accessible to different<br />

services, particularly in the field of ecotourism.<br />

The beaches in the area now generate income for the residents. There is an increase in the demand for<br />

transportation services, mainly for delivery of their fish products.<br />

“Kaming lahat po dito sa apat na barangay nagpapasalamat kami sa <strong>PAMANA</strong>. Nang dahil sa inyo po, nasalba<br />

namin ang aming [buhay]. Panatag na ang aming buhay.”<br />

20

“<br />

Noong araw di ako naniniwala sa<br />

trabaho ng gobyerno, tapos ngayon<br />

biglang na-twist.<br />

Kaming lahat po dito sa apat na<br />

barangay nagpapasalamat kami sa<br />

<strong>PAMANA</strong>. Nang dahil sa inyo po,<br />

nasalba namin ang aming [buhay].<br />

Panatag na ang aming buhay.<br />

”<br />

21

The<br />

Challenged<br />

Volunteer<br />

MAALO, SORSOGON<br />

2

23

“<br />

Natuto din kami noon na magkaroon ng<br />

bayanihan. Kasi noon kahit walang pera,<br />

tinatrabaho na namin yung dapat magawa.<br />

24

<strong>PAMANA</strong> STORIES<br />

THE CHALLENGED<br />

VOLUNTEER<br />

A concrete pathway-- it was Baranggay Maalo’s first project under <strong>PAMANA</strong>. But the money for labor came slow,<br />

too slow for the baranggay. Sadly, the residents blamed it all on bookkeeper Mariflor Enorma.<br />

“Kasi noong <strong>PAMANA</strong> 1, matagal na-grant yung (funds). Tapos yung trabaho namin halos nasa 95% na. Ang<br />

naudlot doon is yung pagbayad sa labor. Nagkaron kami ng issue sa mga tao dahil hindi kami nakapagbayad ng<br />

labor,” Mariflor said.<br />

Money for a project under <strong>PAMANA</strong> comes in tranches. After the second tranche, the barangay decided to<br />

continue the road using the excess cement and aggregates, even if they would not be paid immediately.<br />

“Sabi nila papayag daw sila magtrabaho kahit wala pa raw yung bayad para hindi masayang yung semento.”<br />

They all agreed to get paid on the third tranche.<br />

“Kaso nung tumagal na, maraming issue silang sinabi sa akin. Naubusan na raw ng pera kaya walang madownload.<br />

Ini-radyo pa nila kami.”<br />

Best intentions gone sour, the townspeople even went as far as broadcasting it on the local radio. The fund for the<br />

third tranche arrived on a Wednesday, while the issue went on air on a the following day.<br />

“Masakit sa loob ko na ganoon ang sinasabi nila sa akin.”<br />

The tension was resolved when the fund for the third tranche finally arrived. In the next two <strong>PAMANA</strong> cycles, the<br />

people had a better understanding of the process.<br />

“Natuto din kami noon na magkaroon ng bayanihan. Kasi noon kahit walang pera, tinatrabaho na namin yung<br />

dapat magawa. Advance na palagi yung trabaho.”<br />

Mariflor was a volunteer, but the accusing eyes of her neighbors was a burden she did not sign up for. Still, she<br />

did her job.<br />

“Hindi nalang ako nakinig ng mga sinasabi basta ang akin lang naman po pagdating ng panahon na may<br />

pakinabang na ang ginawa ko para sa kapwa ko maiisip nila ang pakinabang ng isang tulad kong volunteer.”<br />

25

26

NEGROS-PANAY<br />

27

28

29

30

SAMAR ISLANDS<br />

31

Stairs by<br />

the Clif f<br />

MATUGUINAO, SAMAR<br />

32

33

<strong>PAMANA</strong> STORIES<br />

STAIRS BY THE CLIFF<br />

Even before Ethel Elizalde was born, the people of Barangay Maduroto have been used to climb on improvised<br />

stairs on the side of a cliff just to get to the river.<br />

“Mahirap yung pag-akyat at pagbaba doon. Lalo na kung may karga-karga at lalo na yung mga bata.”<br />

At 39, Ethel is a resident of Barangay Maduroto, Matuguinao, Samar for almost four decades now and the routine<br />

had always been like that.<br />

Every day, it takes her 15 minutes to walk from home to the river. It is easy for her to describe how important<br />

the river is to their lives, “Lahat ng pangangailangan namin (nasa ilog).” It is where her family bathe, wash their<br />

clothes, and the likes.<br />

But as integral as the river is, it also poses occassional danger to their family.<br />

“May nahuhulog na mga bata doon. Yung mga matatanda nahuhulog doon na may daladalang palanggana.”<br />

Ethel recalled that around three years ago, an armed encounter in their area forced some kids to panic and run<br />

towards the river.<br />

“Minsan nga noong may mga putukan, doon na nagtatakbuhan yung mga bata galing ilog. Nahuhulog din doon<br />

dahil bangin kasi yun.”<br />

At some point, even the children who brave the cliff every day just to take a bath, felt discouraged to go to the river<br />

anymore-- accounting to fewer kids attending school.<br />

“Minsan di na pumapayag yung mga bata pumunta (sa ilog). Tinatamad na. Di na pumapasok ng school. Lalo<br />

nang tinatamad pag walang tubig (Once in a while, the children refuse to go to school).”<br />

Living with this problem her entire life, Ethel thought the government did not care for their community.<br />

“Parang wala kaming nakikita dahil wala kasing pinagbago noon e. Mahirap talaga noon (We didn’t see any<br />

changes in our lives).”<br />

With the help of PAyapa at MAsaganang PamayaNAn (<strong>PAMANA</strong>), a pathway with a handrail, was built to keep<br />

the residents safe when going to the river.<br />

Now it’s easier for them attend to their daily needs, without having to worry the consequences of one small<br />

misstep or one wrong slip that might cause their life.<br />

“Nakikita na kasi namin ngayon na may pagbabago. Napakadali na ng pagbaba sa amin (We have seen the<br />

changes, now our lives are better).”<br />

34

“<br />

Every day, it takes her<br />

15 minutes to walk from<br />

home to the river. It is<br />

easy for her to describe<br />

how important the river is<br />

to their lives.<br />

”<br />

35

36

Night<br />

Trips<br />

BONIFACIO, NORTHERN SAMAR<br />

37

“<br />

When <strong>PAMANA</strong><br />

reached their<br />

community, their first<br />

project was to build<br />

streetlights in the<br />

baranggay. Marichu<br />

was one of the<br />

volunteers who helped<br />

bring back the light to<br />

their place.<br />

”<br />

38

<strong>PAMANA</strong> STORIES<br />

NIGHT TRIPS<br />

Albeit thinking years ahead, Marichu Maceriano still worries about her children’s future, particularly for their<br />

safety when they go to high school.<br />

“Tatlo na po yata ‘yung napatay sa daan namin,” she said.<br />

The closest high school for Marichu’s children is unfortunately far from the baranggay where they live-- Barangay<br />

Bonifacio. Her kids would have to walk a long path without streetlights.<br />

“Noong wala pa pong streetlights dito sa barangay namin, pag alas-sais po, yung mga tao nasa loob na ng mga<br />

bahay. Wala nang lumalabas.”<br />

But not everybody had the comfort of staying home at night. Sometimes, when the high school students would<br />

leave the school late, their parents would brave the dark just to ensure their children get home safe.<br />

“Hindi mo alam baka may makasalubong kang tao na di mo kilala, kung ano na gawin sa ‘yo.”<br />

When <strong>PAMANA</strong> reached their community, their first project was to build streetlights in the baranggay. Marichu<br />

was one of the volunteers who helped bring back the light to their place.<br />

“’Yung mga tao nakakalabas na pag gabi kasi wala na po silang kinakatakutan kasi maliwanag naman po yung<br />

mga daan.”<br />

Their baranggay tanod can now patrol the area more efficiently because of the streetlights. Even the sari-sari<br />

stores stay open, after a long time, until nightfall.<br />

“Sa mga tinda-tindahan medyo nakatulong din yun sa pamumuhay namin kasi dati alas-sais palang yung mga<br />

tindahan sarado na. Ngayon sila hanggang alas-diyes, nagbukas pa sila. Kaya nakakadagdag income pa sila.”<br />

Marichu has four children, with the eldest being in the fourth grade this year. Now, she does not have to worry<br />

about risking their safety when going to their high school.<br />

“Magiging maganda yung kinabukasan nila. ‘Tsaka magiging matahimik, ‘yung wala silang pinangambahang<br />

takot.”<br />

39

40

DAVAO-COMVAL<br />

- CARAGA<br />

41

Rebel<br />

Gone<br />

Home<br />

MATI, DAVAO ORIENTAL<br />

42

43

<strong>PAMANA</strong> STORIES<br />

REBEL GONE HOME<br />

At the young age of 13, Ronnie* joined the New People’s Army under the pretense of a false hope.<br />

He had always wanted to be a soldier. Obviously, he never planned on ending up as a rebel. All he knew was he<br />

needed to finish school first to be a soldier.<br />

But his mother died in 1989, immediately followed by his father’s death in 1991. Only in his first grade, Ronnie<br />

was already an orphan.<br />

“So, tuluyan na pong dumilim ang inaasahan kong pangarap. Wala na po talaga akong pag-asa na magpatuloy ng<br />

pagaaral. Yung mga magulang ko kasi nabubuhay lang sa pagsasaka.”<br />

An organizer from the communist movement told Nicanor that they would sponsor his education for free to<br />

persuade him to join the group.<br />

“Sa pagkasabi niya na libre, natuwa po ako kasi sabi ko ito na yung daan para marating ko ang aking pangarap.<br />

Hindi ko pa naisip na yung sinasabi nilang libre ay libre din po pag namatay ka dun sa loob.”<br />

Albeit his best intentions for joining, Nicanor, then naïve and idealistic immersed himself to the ideals of the<br />

armed wing of the communist party, eventually forgetting why he joined there in the first place.<br />

“Noong mga panahong iyon nakalimutan na yung pangrap ko na magpatuloy ng pagaaral.”<br />

He listened to lectures on the communist ideology, sang “progressive” songs, and became an echo of the<br />

propaganda.<br />

“Kahit pa naman sino mga bata, kahit pa naman mga binata pa, sa tagal ng pagdisipilina, sa tagal ng pag-ano mo<br />

sa ideolohiya, mapaniwala mo talaga ang sarili mo, mismo ikaw magtiwala ka na ito na talaga yung tama.”<br />

Rebel, Estranged Family Man<br />

Ronnie married a civilian, thinking it would be easier to leave NPA if he was the only one deemed to be loyal to<br />

the communist party. They started to raise a family, despite the circumstance.<br />

Fatherhood reminded him of his failed dream to finish school, and worried his children’s education would suffer<br />

the same fate.<br />

“Kung sa pangarap ko man lang na makapagpatuloy ako ng pag-aaral, hindi ko narating. Pano pa kaya sa mga<br />

anak ko? Ano ang mabigay ko na kinabukasan?”<br />

Each year, rebels that are invisible under the radar of the government, are allowed to go home for five days. But<br />

even with this little freedom, Nicanor knew it wasn’t enough.<br />

4

45

“Alam naman po ng bawat isa yung limang araw sa isang taon ay kulang man po yun.”<br />

“ Kahit na po<br />

ilang taon ako<br />

naging pasaway,<br />

binigyan pa<br />

rin ako ng<br />

pagkakataon<br />

ng pamahalaan<br />

na baguhin ang<br />

pagkakamali<br />

na paningin at<br />

maitama.<br />

”<br />

Even the birthdays of his family weren’t an exception. Giving simple gifts was a luxury their code didn’t allow them to<br />

have.<br />

“Sa rebolusyon walang birthday.”<br />

Happy Homes<br />

In 2013, Nicanor surrendered to the government, exhausted with his life in the NPA. An intelligence officer in the battalion<br />

who sheltered him during his surrender presented an offer.<br />

“Kaya nilapitan ako ng intelligence officer doon sa batallion at tinanong ako kung gusto ko bang magaral. Sabi ko sir kaya<br />

nga nagkalintik lintik yung buhay ko kasi sinugal ko ang sarili ko para lang sana makapag-aral.”<br />

He was invited to go to Happy Home, a government-run shelter in Davao Oriental for rebel returnees that was funded by<br />

DILG-<strong>PAMANA</strong>.<br />

The first of its kind, Happy Home was a brainchild of Davao Oriental Governor Corazon Malanyaon. It provides rebel<br />

returnees a shelter that would facilitate their transition to civilian life, offering them services that ranged from livelihood<br />

training to education.<br />

One of the services offered is the Alternative Learning System (ALS). This program gave Nicanor a second shot at his<br />

dream to finish school.<br />

According to the Department of Education, the ALS is a program that provides for individuals who did not have access<br />

to formal education. They are given “the chance to have access to and complete basic education in a mode that fits their<br />

distinct situations and needs.”<br />

He said over 30 returnees joined him in the program. Some finished elementary before being part of NPA. Some got as<br />

far as second year high school.<br />

When asked for his educational attainment, Nicanor pretended to be a few years ahead.<br />

“Ang nilagay ko po doon is grade 5 kahit na alam ko na grade 1 lang po ako. Baka sakali kung grade 5 i-enroll nya ako sa<br />

grade 6.”<br />

The personal information system, which required him to state his educational attainment, also included a set of questions<br />

to determine his academic capacity.<br />

Despite only reaching first grade, Ronnie’s test scores earned him a place in the secondary level of ALS.<br />

He passed the national exam in 2014. A year later, Happy Home enrolled him in TESDA, where he took up the course in<br />

welding.<br />

He is currently undergoing a series of examinations and application processes to finally join the Armed Forces of the<br />

Philippines.<br />

Ronnie never expected the turn of events that brought him from the NPA to back, and now a chance to be part of AFP.<br />

“Kahit na po ilang taon ako naging pasaway, binigyan pa rin ako ng pagkakataon ng pamahalaan na baguhin ang<br />

pagkakamali na paningin at maitama.”<br />

____________________________________<br />

*His real name was changed for security reasons.<br />

46

The Human<br />

Cost of<br />

Broken Roads<br />

CANTILAN, SURIGAO DEL SUR<br />

47

“ She says their<br />

life is much<br />

different<br />

now. The<br />

road makes<br />

important<br />

services<br />

accessible to<br />

them.<br />

48

<strong>PAMANA</strong> STORIES<br />

THE HUMAN COST OF<br />

BROKEN ROADS<br />

For nearly all her life in Barangay Lobo, Renita Conejo had grown used to finding her way along a rough road, with no lights at all to keep<br />

her safe in the dark.<br />

“Noon ang biyahe umaabot sa 5 hours,” she said, when asked to talked about going to the town.<br />

The people of Barangay Lobo make crops of cassava, sweet potato, and corn. But they often spend more for the ride than what they earn for<br />

profit.<br />

“Kung magbebenta kami sa baba, hindi nagkakasiya yung benta sa pamasahe namin.”<br />

It cost 100 pesos to go to town. A pack of rice would cost around 500 pesos while other products cost 15 pesos per kilo.<br />

“Kahit nga yung asin mura lang pag binili pero mas mahal pa ang pamasahe namin kaysa sa presyo ng asin.”<br />

But the problem they experience goes beyond what they could afford.<br />

Human Cost<br />

For people in need of medical attention, their health is compromised both from staying in local health center and in braving the broken<br />

road to reach a hospital. The road going to the town is rough and uneven, an uncomfortable ride even for perfectly healthy individuals,<br />

which is more unsettling for pregnant women. She tells the story of her pregnant auntie who had to overcome odds just to deliver her baby<br />

safely. After three days of labor, her auntie decided to take her chances, riding on the side seat of a habal-habal. A habal-habal is a two-wheel<br />

motorcycle with improvised seats on each side.<br />

“Umupo yung tiyahin ko sa siding ng motor, tatlong araw na siya naglalabor doon sa amin. Noong nadala lang sa ospital, malapit nang<br />

mamatay. Hindi na umabot.”<br />

Renita’s grandfather suffered the same fate. His grandfather, however, decided to stay, despite being terribly ill.<br />

“Noon yung lolo ko sinabi sa amin na wag na lang siyang isakay sa motor. Wag na siyang dalhin sa ospital kasi sa daanan lang din siya<br />

mamatay dahil sa hirap ng daan. Doon na lang siya namatay [sa amin].”<br />

<strong>PAMANA</strong><br />

With the help of <strong>PAMANA</strong>, a farm to market road is being constructed in Barangay Lobo. Renita says that it has greatly reduced the time<br />

spent commuting.<br />

“Ngayon 1 hour na lang mula sa kampilan ng sundalo hanggang sa Barangay Lobo.”<br />

Since power shortage was also a problem in their community, each is awarded with a solar panel to light up their home. The school in<br />

their community even has a solar panel large enough to power a television for the children’s education. She says this has also helped them<br />

communicate with each other as it allowed them to charge their phones.<br />

“Ngayon na may ilaw na, ang galing na talaga.Nararanasan na namin ang buhay na katulad ng nasa munisipyo sa bayan.”<br />

She says their life is much different now. The road makes important services accessible to them.<br />

“Iba na talaga ang nararanasan namin. Noon parang nawalan na kami ng pag-asa. Akala namin hindi na kami uunlad.”<br />

49

50

CENTRAL<br />

MINDANAO<br />

51

52

Old School<br />

TANGCLAO, LANAO DEL NORTE<br />

53

<strong>PAMANA</strong> STORIES<br />

OLD SCHOOL<br />

Nailiya Nasroden, on her prime years in elementary, hiked for an hour every day to get to school.<br />

“Yung road doon lubak-lubak. Pag umuulan masyadong madulas, pag mainit naman hindi nila kaya yung init.”<br />

She did this routine for two years until, one day, she decided to just study at home instead.<br />

“Parang yung mga teachers namin hindi kami masyado binibigyan ng attention kasi parang pagdating nila<br />

pagod sila kasi nga yun nga nagha-hike dahil sa daan. Kami rin pagod kami. So instead na magaral kami parang<br />

nagrerelax lang, so ayun tinatamad kami, nawawala yung interes, yung motivation.”<br />

Along with her cousins, Nailiya didn’t go to school for three straight days. Then she talked to her parents, “Sabi<br />

nila since parang wala kayong mapapala dito kung dito kayo mag-elementary. So naisipan nilang palipatin kami.”<br />

It was a difficult decision for Nailiya.<br />

“Parang mas madali matuto doon. Kilala mo na yung mga tao doon. Parang yun nga parang sanay na ako sa aura<br />

ng place namin.”<br />

It pitted familiarity against convenience, but at some point she would eventually feel school days less of a burden.<br />

“Parang may side sa akin na masaya kasi di na totally mahirap yung lalakarin ko everyday. Meron ding side sa<br />

akin na malungkot kasi nga mas gusto [ko] doon na sana kaso mahirap kasi.”<br />

Visiting her hometown, she noticed how much has changed.<br />

“Parang since naayos na yung daan, mas dumami yung students doon. Mas dumami yung students nila. Mas namotivate<br />

yung mga students mag-aral kasi madali na yung daan e. Hindi na mahirap katulad ng dati.”<br />

With the help of <strong>PAMANA</strong>, students and teachers alike need not to hike to reach the school anymore.<br />

Nailiya will soon start her first year in college, pursuing a major in education to pursue her dream of teaching in<br />

her hometown.<br />

54

“<br />

With the help of <strong>PAMANA</strong>, students and teachers alike<br />

need not to hike to reach the school anymore.<br />

”<br />

55

Travel<br />

Time<br />

MUNAI, LANAO DEL NORTE<br />

56

57

<strong>PAMANA</strong> STORIES<br />

TRAVEL TIME<br />

It took Nasser nearly eight hours to transfer his harvest of corn and copra to a market in Barangay Linamon.<br />

“Pag [alis] namin sa Mamula ng alas otso, dating namin ng Linamon mga hapon, mga alas kwatro,” he said.<br />

Sometimes, he would sleep in a relative’s home because the roundtrip is too long. In other occasions, he would<br />

brave the road and would get home before dawn.<br />

“Minsan pagbalik namin sa bahay mga alas-kwatro ng umaga.”<br />

But his fatigue was often just for a naught as his earned profit is drained because of transportation dues.<br />

“Pag makabenta kami ng 7,000 [pesos], ang matitira sa amin 1,000 [pesos]. ‘Yan ang pinakaswerte.”<br />

Daily living depended mostly on the mercy of their luck every harvest season. Transportation costs Php 1.50 per<br />

kilo, sometimes even reaching as much as Php 2.<br />

On an average, he would bring 1,500 kilos to 2,000 kilos of corn. For the truck to carry his products, he would<br />

have to pay over Php1,000 to make ends meet.<br />

“Minsan kung walang swerte, walang matitira. Kung konti lang nakuha sa mais, mas mahal yung fertilizer, [pati<br />

yung] abono.”<br />

Life was difficult even in matters outside of the farm.<br />

“Medyo hindi kami masaya. ‘Pag gusto namin may pupuntahan, pag-iisipan pa. Kasi alam namin ang mangyayari<br />

diyan, mahihirapan kami.”<br />

With the help of <strong>PAMANA</strong>, a farm-to-market road evidently reduced travel time and expenses for Nasser.<br />

At present, it only takes them 40 minutes to get to Linamon compared to his usual eight-hour travel.<br />

The cost per kilo has also stablized to just one peso, making room for more profit to grow.<br />

“Ngayon pag mais, halimbawa makabenta kami ng mga 10, 000 [pesos], may natitira nang minsan na 4,000 o<br />

3,000 [pesos] plus. Tumaas yung natitira sa amin.”<br />

A lot has changed since <strong>PAMANA</strong> arrived in their community. With better road comes better access to important<br />

social services.<br />

“Kung wala yan, mahirap ang buhay namin dito sa Punong Poonapieyopo.”<br />

58

59

60

Beyond<br />

Halfway<br />

ISULAN, SULTAN KUDARAT<br />

61

<strong>PAMANA</strong> STORIES<br />

BEYOND HALFWAY<br />

Whenever it rains hard in Baranggay Lagandang, Sultan Kudarat, a flashflood rolls down from the mountain,<br />

obstructing the road with wooden debris and render the road difficult to pass.<br />

“Mahirap kasi tuwing umuulan ay nagkakaroon ng flash flood. Hindi kami makadaan dahil sa lakas ng ulan at ng<br />

baha doon. Natutumba ang mga kahoy kaya hindi lang farmers, pati rin yung mga mamayan doon sa baranggay<br />

ay apektado ng flashflood.”<br />

According to Anwar Sailila, it normally costs around 50 pesos to transport one sack of rice with a ¬habal-habal<br />

(hired motorcycle) from their baranggay to the market. But when it rains, the price doubles.<br />

“Kapag sira ang daan dahil sa baha, hindi pumapayag ang mga habal-habal na 50 pesos lang ang bayad. Mahirap<br />

naman talaga. Hindi rin nila nadadala ang marami. Dalawang sako yung iba, [minsan] isang sako lang.”<br />

From there, they would travel to Isulan, a municipality in Sultan Kudarat, to look for a trader that would buy their<br />

products. But by then, their crops would have suffered beating from the ride, making it difficult to settle with a<br />

decent price.<br />

“Hindi mo alam kung saan ibebenta ng maganda ang produkto,” Sailila said. “Dati kasi noong minsan ang habalhabal,<br />

pinagpatong-patong nila yung mga produkto.”<br />

With the help of <strong>PAMANA</strong>, a farm-to-market road was developed in their community to help ease the transport<br />

of their harvest. As of this writing, the construction is still ongoing, but the residents already benefit from the<br />

widened road.<br />

The price of transportation has reduced greatly, costing around 40 pesos for either sack or person.<br />

Even better for the farmers, transporting their goods themselves in search for dealers is no longer necessary.<br />

“Yung mga negosyante sa Isulan, ngayon sila na ang pumapasok sa barangay para mag buy-and-sell,” Sailila said<br />

and added, “Nakabawas ng hassle yun para sa mga residenteng nagne-negosyo sa baranggay kasi hindi na sila<br />

mamamasahe palabas ng baranggay para sa produkto.”<br />

To make the most out of the available harvest, the dealers even offer a higher price.<br />

“Noon kami yung naghihirap. Sasakay ka pa ng malayo tapos iba-iba pa yung presyo nila. Ngayon baliktad na.<br />

Ngayon sila na ang nagcacanvass sa amin.”<br />

Baranggay Lagandang is a Peace and Development Community and a former MNLF base that is mow committed<br />

to lasting peace in accordance with the 1996 GPH-MNLF Final Peace Agreement.<br />

62

63

64

ZAMBA<br />

SULTA<br />

65

Waterworks<br />

TALUSAN, ZAMBOANGA SIBUGAY<br />

6

<strong>PAMANA</strong> STORIES<br />

WATERWORKS<br />

When Orlando Temporanda’s daughter was seven, she told Orlando that she might not finish school anymore.<br />

“Sabi niya sa akin, ‘Tay baka di na ako makaabot ng high school o pati sa college’. Sabi ko bakit ‘man. Sabi niya<br />

mahirap ngayon kasi malayo tubig sa ating bahay. Magskwela siya pero ma-late pa raw siya.”<br />

Around 100 kilometers stand between the nearest water source and Barangay Kawilan, where Orlando and his<br />

family lives.<br />

Shared among an entire community, there are four deep wells given by DPWH and six open wells made by the<br />

residents themselves.<br />

Riding on a carabao, Orlando would put basins in a cart to fetch water in the wells. Travel time for this errand can<br />

take as long as an hour.<br />

“Doon kami maligo. Doon maglaba. Doon mag-inom. Kaya ang problema namin hindi safe ang tubig namin kasi<br />

open ‘man yun. Baka meron mangitlog na mga lamok tapos magkasakit ‘yung mga bata.”<br />

Maris Temporada, his daughter, would often go to school late from waiting for her turn at the well with the whole<br />

barangay.<br />

“Nagdala lang ng tubig isakay namin sa kalabaw. Yung limang galon, pag nandun sa bahay, yun ang aming<br />

ipapainom sa baboy, sa manok, o pati sa baka.”<br />

With the help of <strong>PAMANA</strong>, a water tank was built within the community. Making the source of water more<br />

accessible for Orlando and his neighbors.<br />

“Ngayon sir malapit na sa amin (‘yung water system). Source namin nandoon sa barangay hall. Sa barangay site<br />

yung tanke namin.”<br />

Through hard work and persistence, his daughter finished high school and now on her third year in college,<br />

taking up a degree on Agribusiness.<br />

67

BUSINESS STALLS IN<br />

ZAMBOANGA ZIBUGAY<br />

Edit ipsaestio occab ime min cus milique net quam,<br />

coremquas et fuga. Ut el ipsunt. Apic te veriberovid<br />

maximus aliquae sandae omnis ditiori busandel id<br />

quatae. Sin con preribus aut volumque pa cor sequis<br />

et estis nobiscipsa volest, cusant modi occaboria quiat<br />

fuga. Ut moluptat. Ut reprae nam nem voluptatatis adi<br />

officiis arum adisciet aditaqu odicipsunt.<br />

Tionsequi to et qui odites explandis ma quia volores<br />

ciaecae pori dit, cusa quas dem voluptatio. As sitatur<br />

aut odiores quae. Itatempores ipsumquodit quiam<br />

voluptatur, sequi<br />

68

PEACE CENTER CONVERED COURT IN ZAMBOANGA ZIBUGAY<br />

Edit ipsaestio occab ime min cus milique net quam, coremquas et fuga. Ut el ipsunt. Apic te veriberovid maximus aliquae sandae omnis ditiori<br />

busandel id quatae. Sin con preribus aut volumque pa cor sequis et estis nobiscipsa volest, cusant modi occaboria quiat fuga. Ut moluptat. Ut<br />

reprae nam nem voluptatatis adi officiis arum adisciet aditaqu odicipsunt.<br />

Tionsequi to et qui odites explandis ma quia volores ciaecae pori dit, cusa quas dem voluptatio. As sitatur aut odiores quae. Itatempores<br />

ipsumquodit quiam voluptatur, sequi<br />

69

70

71

Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process (OPAPP)<br />

The Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process or OPAPP is the office<br />

mandated to oversee, coordinate, and integrate the implementation of the<br />

comprehensive peace process. The agency was created through executive order no. 125,<br />

s. 1993 which was later amended in 2001 with the signing of executive order no. 3, s. 2001<br />

as a reaffirmation of the government’s commitment to achieving just and lasting peace<br />

through a comprehensive peace process.<br />

PARTNERS<br />

72