Hackley Review Summer 2015: Lower School Science

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

FEATURE<br />

30<br />

By Amanda Esteves-Kraus<br />

Discovering Magic:<br />

Regina DiStefano and <strong>Hackley</strong> <strong>Lower</strong><br />

<strong>School</strong> <strong>Science</strong><br />

This article is part of a series on faculty holders of <strong>Hackley</strong>’s endowed chairs. Regina<br />

DiStefano was named to The Parents’ Chair for a three year term, beginning in 2013.<br />

The Chair was endowed by the <strong>Hackley</strong> Parents’ Association to recognize excellence in<br />

teaching and is awarded to faculty following nomination by their faculty peers.<br />

Full disclosure: children under the age of 10 scare me.<br />

I spend my days in the science classrooms of the<br />

Upper <strong>School</strong>—teaching biology to juniors and<br />

seniors—and my conversations with students occur<br />

at eye level. So it was with some trepidation that<br />

I entered the <strong>Hackley</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong>—a beautiful<br />

building sized for individuals who barely reach my<br />

hip—to gather my research on Regina DiStefano.<br />

I say “research” because over the last few months,<br />

I poked and prodded many individuals in order to<br />

gather data on Regina and <strong>Hackley</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong><br />

science. Scientists know that only with data can you<br />

formulate a conclusion. Let me share with you some<br />

numbers that I picked up on my first day of this<br />

social experiment.<br />

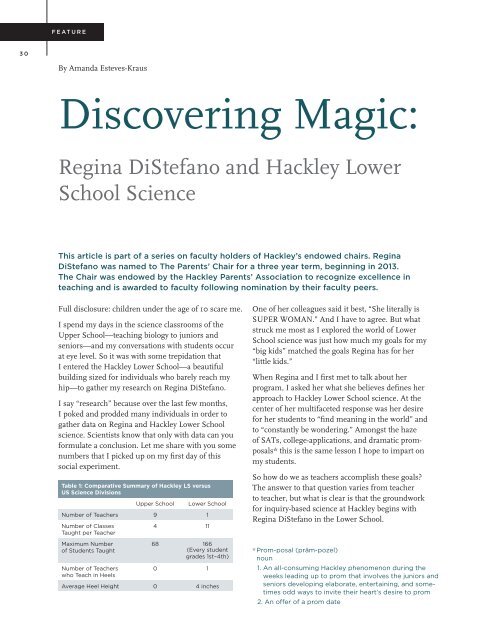

Table 1: Comparative Summary of <strong>Hackley</strong> LS versus<br />

US <strong>Science</strong> Divisions<br />

Upper <strong>School</strong><br />

<strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong><br />

Number of Teachers 9 1<br />

Number of Classes<br />

Taught per Teacher<br />

Maximum Number<br />

of Students Taught<br />

Number of Teachers<br />

who Teach in Heels<br />

4 11<br />

68 166<br />

(Every student<br />

grades 1st–4th)<br />

0 1<br />

Average Heel Height 0 4 inches<br />

One of her colleagues said it best, “She literally is<br />

SUPER WOMAN.” And I have to agree. But what<br />

struck me most as I explored the world of <strong>Lower</strong><br />

<strong>School</strong> science was just how much my goals for my<br />

“big kids” matched the goals Regina has for her<br />

“little kids.”<br />

When Regina and I first met to talk about her<br />

program, I asked her what she believes defines her<br />

approach to <strong>Hackley</strong> <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong> science. At the<br />

center of her multifaceted response was her desire<br />

for her students to “find meaning in the world” and<br />

to “constantly be wondering.” Amongst the haze<br />

of SATs, college-applications, and dramatic promposals*<br />

this is the same lesson I hope to impart on<br />

my students.<br />

So how do we as teachers accomplish these goals?<br />

The answer to that question varies from teacher<br />

to teacher, but what is clear is that the groundwork<br />

for inquiry-based science at <strong>Hackley</strong> begins with<br />

Regina DiStefano in the <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong>.<br />

* Prom-posal (präm-pozel)<br />

noun<br />

1. An all-consuming <strong>Hackley</strong> phenomenon during the<br />

weeks leading up to prom that involves the juniors and<br />

seniors developing elaborate, entertaining, and sometimes<br />

odd ways to invite their heart’s desire to prom<br />

2. An offer of a prom date

31<br />

<strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong> science students building cars they will later race, testing the effects of friction and other forces. The project is<br />

part of a unit on simple machines; cars combine levers, wheels and axles.<br />

Families touring <strong>Hackley</strong> will often say the school<br />

resembles Hogwarts. If so, then Regina’s second-floor<br />

classroom is that magical room at the top of several<br />

moving staircases that manages to make you feel<br />

that you are no longer inside, but instead exploring<br />

the natural world outside. Windows cover one entire<br />

wall of the <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong> science classroom. When<br />

I walked in for the first time, I felt enveloped in the<br />

trees. None of the surrounding school buildings or<br />

neighborhood houses were visible. Instead, the view<br />

was a panorama of tree branches, the sky, and birds<br />

as they flitted past the windows. In elementary school,<br />

teachers chastised me for staring out the window; this<br />

classroom would have been my downfall.<br />

Luckily, what I soon discovered was that the inside<br />

of the classroom was just as lively and magical as the<br />

outside world. Old hornets’ hives and birds’ nests<br />

hang from the ceiling. Colorful solar system projects<br />

cover another wall. There are books everywhere,<br />

posters of local bird species, and reconstructed owl<br />

pellets. And just when I began to border on sensory<br />

overload, my eyes landed on what might be the bestkept<br />

secret of <strong>Hackley</strong>—the <strong>Science</strong> Word Wall. It is<br />

a wall full of science vocabulary. Words like “crenate,”<br />

“arachnid,” “conduction,” and “momentum” stand<br />

proudly on the wall in big, glossy, black letters.<br />

True magic!<br />

You may think I am the biggest nerd for falling in<br />

love with this wall, but when I told my juniors and<br />

seniors about this phenomenal creation—well, actually,<br />

first they did laugh at me—but then they started<br />

pestering me to create their own <strong>Science</strong> Word<br />

Wall in my classroom. At the core of all sciences,<br />

but especially biology, is a bevy of new vocabulary.<br />

I often write on graded assessments, “Please use<br />

your science vocabulary.” The smooth endoplasmic<br />

reticulum produces lipids, whereas the rough endoplasmic<br />

reticulum produces proteins. Fail to delineate<br />

the adjective, smooth or rough, and it is impossible to<br />

know this particular organelle’s function. Even within<br />

these two sentences, new questions pop up in relation<br />

to vocabulary; “What is a lipid again? An organelle?”<br />

It can be never-ending—hence the begging for an<br />

Upper <strong>School</strong> <strong>Science</strong> Word Wall.<br />

When I asked Regina about the Word Wall, she told<br />

me it was “just the best” classroom aid, reminding<br />

students to focus on what they say and how they say<br />

it. Exploring and discovering meaning is all well and<br />

good, but without the basic skill set of vocabulary,<br />

students cannot ask the appropriate questions. It<br />

is not enough in Regina’s classroom to say “seethrough”<br />

when “transparent” is on the Word Wall.<br />

She believes students “feel better and more capable if<br />

the work is hard for them,” and part of that capability<br />

is appropriate use of science vocabulary.<br />

This conversation about language underscores a<br />

central tenant of effective science education. These<br />

days, the buzz in science education is all about<br />

“STEM,” and many curricula—and more important,<br />

many students—seek to compartmentalize<br />

STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math)<br />

as subjects completely detached from humanities<br />

classes. Not only does this reinforce old stereotypes,<br />

encouraging those students who naturally gravitate

FEATURE<br />

32<br />

Students take advantage of <strong>Hackley</strong>’s largest classroom—our woods!<br />

A fourth grader displays the result of owl pellet dissection.<br />

to quantitative subjects to justify their resistance to<br />

the humanities while marginalizing those who more<br />

naturally gravitate to literature and arts, it fundamentally<br />

detracts from the depth with which each student<br />

can engage with the subject. Through language we<br />

not only learn and build a stronger foundation, but<br />

also unlock other doors.<br />

“Endo,” for example, derives from the Greek endon,<br />

which means “within.” Understanding this, we can<br />

conclude that both the smooth and rough endoplasmic<br />

reticulum must be within something. My<br />

first year teaching at <strong>Hackley</strong>, a student floored me<br />

by nonchalantly stating, “Of course, the function of<br />

the cloaca [an opening in birds for the release of both<br />

excretory and reproductive products] makes sense<br />

because the Latin association of the word is ‘sewer.’”<br />

With this observation, this student engaged every<br />

other student in the classroom and ensured that no<br />

one would ever forget the term cloaca.<br />

And this is what I think is so phenomenal about<br />

Regina. She understands and manages to create a<br />

science classroom that is incredibly hands-on and<br />

inquiry-based without losing sight of the other skills<br />

students need to have to simply be good students.<br />

One of the days I visited Regina’s class was a day<br />

she deemed “a boring day” because her first grade<br />

students were doing research for their research<br />

projects. Now, I do not know what you were doing<br />

in your school in first grade, but I can assure you, I<br />

was most certainly not involved in research of any<br />

kind. And yet here was a classroom of little people, all<br />

focused on gathering information on their assigned<br />

animals. To make them feel special, and to keep<br />

them focused, Regina set-up blue cardboard dividers<br />

around students to create the feeling of cubicles.<br />

Regina notes, “Students need to learn to look at<br />

sources, understand and question where information<br />

comes from, and draw conclusions from what they<br />

gather—facts or data.” With the amount of information<br />

available to students instantaneously these days,<br />

it is never too early to learn this lesson.<br />

In my conversations with students, parents, and<br />

colleagues, it is clear that <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong> science is fun.<br />

Regina said it best when she told me she loves her job<br />

because she “gets to play all day long.” Students build<br />

racecars and race them in the hallway. The different<br />

modes of heat transfer—conduction, convection, and<br />

radiation—became a delicious lesson when taught<br />

through the vector of popcorn.<br />

A current senior who had Regina in third grade<br />

distinctly remembers the still popular catapultbuilding<br />

activity. The assignment is to build a catapult<br />

out of pieces of wood, paper, glue, and rubber bands.<br />

The activity focused on trial, error, and recording<br />

of results, in order to learn from each attempted<br />

design—in short, the real-life scientific method. He<br />

recalled that his catapult “worked terribly, but it was<br />

a lot of fun to build.” Whenever I perform dissections<br />

with my students, the <strong>Hackley</strong> lifers always—and I<br />

mean always—remember dissecting the owl pellet in

33<br />

<strong>Hackley</strong> 4th graders and kindergartners at the Wolf Conservation Center.<br />

The Wolf Project<br />

The swan song of <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong><br />

<strong>Science</strong> is the WOLF UNIT. Regina<br />

DiStefano developed the project at<br />

the encouragement of Ron DelMoro,<br />

former <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong> Director. The<br />

project engages <strong>Hackley</strong> students<br />

in two partnerships: the first, with<br />

the Wolf Conservation Center<br />

located in South Salem, NY, and the<br />

second pairs <strong>Hackley</strong> fourth graders<br />

and their Kindergarten “buddies.”<br />

The Kindergarten Buddy partnership<br />

extends back decades, as<br />

<strong>Hackley</strong>’s oldest <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong><br />

students (once fifth graders, but<br />

fourth graders since 2004 when fifth<br />

grade joined the Middle <strong>School</strong>),<br />

partner with <strong>Hackley</strong>’s youngest<br />

students at the start of the school<br />

year, and this relationship blossoms<br />

throughout the year through joint<br />

snack sessions, mini “peer advisory”<br />

meetings, and other activities. At<br />

the end of the year, the kindergartners<br />

sing to the fourth graders at<br />

Step-Up Day.<br />

As the fourth graders begin to learn<br />

everything there is to know about<br />

wolves, they share this information<br />

with their buddies. Regina’s unit<br />

encompasses ecology, biodiversity,<br />

predation habits, and endless other<br />

new vocabulary terms. She uses the<br />

wolf as a framework for studying<br />

the local environment and changing<br />

weather patterns. Meanwhile,<br />

however, the kindergartners read<br />

fiction stories that portray wolves<br />

as “bad,” evil creatures. <strong>Hackley</strong><br />

fourth graders share knowledge<br />

that expands the kindergartners’<br />

perspectives so the younger<br />

students may come to appreciate<br />

wolves as more than just fairy<br />

tale villains.<br />

Come springtime, the fourth graders<br />

and their kindergarten buddies<br />

travel to the Wolf Conservation<br />

Center where they get to see live<br />

wolves and ask questions of the<br />

naturalists at the Center. Their<br />

questions reveal the depth of the<br />

knowledge they have gained over<br />

the course of the years. “Why do<br />

the red wolves only have numbers<br />

when the ambassador wolves have<br />

names?” (4th grader). “Can red<br />

wolves and gray wolves breed with<br />

each other?” (4th grader). “Does it<br />

hurt when the elk lose their antlers?”<br />

(kindergartner). “Why do the wolves<br />

pace back and forth like that?”<br />

(4th grader). “How come the wolf<br />

doesn’t like you?”(kindergartner).<br />

The Wolf Unit is one of the staples<br />

of the <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong> science<br />

program that students look forward<br />

to each year. The current fourth<br />

graders can now remember when<br />

they were kindergartners and visited<br />

the Wolf Center with their own<br />

fourth grade buddies. The project<br />

continues to grow and flourish.<br />

Most important, however, by the<br />

end of the unit, students learn that<br />

the “Big, Bad, Wolf” does not really<br />

exist. Regina observes, “If I’m doing<br />

my job right, the students should<br />

understand there really is no such<br />

thing as a ‘bad’ animal.”

FEATURE<br />

34<br />

The <strong>Science</strong> Word Wall<br />

<strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong>—slowly pulling apart the regurgitated<br />

pellet looking for bones that they have to then rebuild<br />

into a complete mouse skeleton. Students learn to<br />

identify the bones not only by structure, but also by<br />

name. This activity is time-consuming, meticulous<br />

work that requires attention to detail and patience.<br />

These are the moments that resonate with <strong>Hackley</strong><br />

students. <strong>Science</strong> is a living, breathing, constantly<br />

evolving process, and if done properly, a fun process<br />

as well. My current students do not remember doing<br />

research in Regina’s class. They do not remember<br />

her focus on the scientific method and using proper<br />

terminology. What they do remember are the owl<br />

pellets, the final fourth grade “Wolf Unit” [see<br />

previous page], and the opportunity to venture out<br />

and explore the 250 or so acres of woods on <strong>Hackley</strong>’s<br />

285 acre campus. But whether the students who have<br />

gone through the <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong> are aware of it or<br />

not, this strong foundation is lodged in their brains.<br />

I see it everyday in my classroom and outside of<br />

my classroom.<br />

When I say outside, I mean outside. My classes trek<br />

through the wilds of <strong>Hackley</strong> regularly. Upper <strong>School</strong><br />

Biology and Ecology teacher Tessa Johnson’s Ecology<br />

classes are in the woods every day. Often, Tessa’s<br />

students pair up with Regina’s <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong> students<br />

to check for salamanders in varying locations in the<br />

woods. These Upper <strong>School</strong>-<strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong> student<br />

partnerships continue throughout the year and<br />

often evolve to lasting devotion. (One <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong>er<br />

frequented the sports games of his Upper <strong>School</strong><br />

“salamander buddy.”) The Upper <strong>School</strong> students are<br />

amazed by how much knowledge of science and the<br />

woods the little people have and it is all a testament<br />

to Regina. She introduces the students to the <strong>Hackley</strong><br />

woods, to the plants and animals local to the area, and<br />

all the while holding the students accountable for the<br />

proper names of species, and encouraging them to view<br />

the world with wider eyes.<br />

Tessa and I have hatched ducks in our classroom for the<br />

last three years. The level of craziness in our classroom<br />

the first few days after the ducks hatch may in fact rival<br />

prom-posal season. Regina brings many of her science<br />

classes to visit the ducks throughout the process—from<br />

eggs, to hatchlings, to toddler ducks. Tessa and I take<br />

turns talking to the <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong>ers who come to visit.<br />

Often our Upper <strong>School</strong> students will even take over and<br />

speak. It’s wonderful to watch the Upper <strong>School</strong>ers step<br />

into these responsible roles and tread into the world of<br />

communication with youngsters. We are always struck<br />

by how observant Regina’s students are. They notice<br />

how the water rolls of the ducks’ oily feathers, or can<br />

point out bloods vessels in the developing embryo while<br />

it is still in the egg.<br />

My Upper <strong>School</strong>ers are always surprised to find how<br />

smart and curious Regina’s students are and I have<br />

to remind many of them that I am sure they were like<br />

that in <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong>. They shrug and respond, “debat-

35<br />

Testing reflexes<br />

Success in machine building—it moves!<br />

[Regina] introduces the students to the <strong>Hackley</strong> woods, to the plants and animals<br />

local to the area, and all the while holding the students accountable for the proper<br />

names of species, and encouraging them to view the world with wider eyes.<br />

able.” Once the little people leave our classroom, the<br />

overall energy level of the room immediately drops<br />

and there is a quiet moment of reflection. Another<br />

<strong>Hackley</strong> lifer informed me that she loved when the<br />

<strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong>ers visit because she remembers being<br />

a kindergartner and having a fourth grade “buddy”<br />

during Regina’s legendary “Wolf Unit.” She once<br />

thought her fourth grade “buddy” was the coolest<br />

person ever and couldn’t image being on the brink<br />

of leaving <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong> to enter Middle <strong>School</strong>. Now<br />

this lifer is about to graduate from <strong>Hackley</strong>. I say<br />

graduate intentionally, because I do believe once you<br />

are part of <strong>Hackley</strong>, you never truly leave <strong>Hackley</strong>.<br />

But when this student does leave <strong>Hackley</strong>, I know that<br />

she will leave with a strong foundation in science that<br />

all started with Regina. She will leave with a desire<br />

to explore the world around her, a desire to question,<br />

and with a fondness for owl pellets. Most important,<br />

she will graduate with the knowledge that there are<br />

certain key skills—language, writing, communication,<br />

the importance of sources—that not only apply to<br />

science, but have also been key elements of her many<br />

other <strong>Hackley</strong> classes.<br />

This is what makes Regina so outstanding as a<br />

teacher. As one of her colleagues noted, “Our <strong>Lower</strong><br />

<strong>School</strong> students are taught the same procedure for<br />

conducting an experiment as the Middle and Upper<br />

<strong>School</strong> students as they formulate a hypothesis and<br />

either prove or disprove it methodically.” Regina<br />

makes it fun and creative without losing academic<br />

rigor and while building stronger students. Not to<br />

mention, she’s doing all of this in heels.<br />

After spending this time in the <strong>Lower</strong> <strong>School</strong> world,<br />

I realize that in so many ways, my students are really<br />

just Regina’s students trapped in big bodies. There<br />

is no such thing as <strong>Lower</strong>, Middle, or Upper <strong>School</strong><br />

<strong>Science</strong> at <strong>Hackley</strong>. There is only <strong>Hackley</strong> <strong>Science</strong>.<br />

And Regina is its foundation.<br />

Ω Amanda Esteves-Kraus joined the <strong>Hackley</strong> <strong>Science</strong><br />

faculty in 2012 after completing her undergraduate degree<br />

at Williams College, where she majored in Biology and<br />

Art History. A member of <strong>Hackley</strong>’s Boarding faculty, she<br />

also conducts Upper <strong>School</strong> Admissions interviews and<br />

serves as Unity Alumni Coordinator in <strong>Hackley</strong>’s Upper<br />

<strong>School</strong> Diversity program. She begins graduate work<br />

in Biology at Teachers College, Columbia University,<br />

in September.