00050

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

IJRPC 2011, 1(3) Srinivasan et al. ISSN: 22312781<br />

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN PHARMACY AND CHEMISTRY<br />

Available online at www.ijrpc.com<br />

Review Article<br />

ADVERSE DRUG REACTION-CAUSALITY ASSESSMENT<br />

Srinivasan R* and Ramya G<br />

PES College of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmacy Practice, 50 Ft. Road, Hanumanth Nager,<br />

Bangalore, Karnataka, India.<br />

*Corresponding Author: cdmseena@gmail.com<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are considered<br />

as one among the leading causes of morbidity<br />

and mortality 1 . .The epidemiological<br />

importance of ADR is justified by its high<br />

prevalence rate – they cause from 3% to 6% of<br />

hospital admissions at any age, and up to 24%<br />

in the elderly population; they rank fifth<br />

among all causes of death and, moreover, they<br />

represent from 5 to 10% of hospital costs 2 . and<br />

is a great cause of concern to the medical<br />

profession. Every occasion when a patient is<br />

exposed to a medical product, is a unique<br />

situation and we can never be certain about<br />

what might happen. A good example for this<br />

is thalidomide tragedy in late 1950s and<br />

1960s.Thalidomide prescribed as a safe<br />

hypnotic to many thousands of pregnant<br />

women caused severe form of limb<br />

abnormality known as phocomelia in many of<br />

the babies born to those women. It was a<br />

seminal event that led to the development of<br />

modern drug regulations aimed to identify,<br />

confirm and quantify ADRs. An adverse drug<br />

reaction (ADR) is any undesirable effect of a<br />

drug beyond anticipated therapeutic effects<br />

occurring during clinical use 14 . Hence every<br />

health care professional who give advice to<br />

patients need to know the frequency and<br />

magnitude of the risks involved in medical<br />

treatment along with its beneficial effects.<br />

Recent epidemiological studies estimated that<br />

ADRs are fourth to sixth leading cause of<br />

death 3 . It has been estimated that<br />

approximately 2.9-5% of all hospital admission<br />

are caused by ADRs and as many as 35% of<br />

hospitalised patients experience an ADR<br />

during their hospital stay 4 . An incidence of<br />

fatal ADRs is 0.23%-0.4%. 5 Although many of<br />

the ADRs are relatively mild and disappear<br />

when drug is stopped or dose is reduced,<br />

others are more serious and last longer.<br />

Therefore there is a little doubt that ADRs<br />

increase not only morbidity and mortality but<br />

also add to the overall health care cost 6, 7 .<br />

Adverse drug reaction (ADR)<br />

Definitions of ADRs exist, including those of<br />

the World Health Organization (WHO) 8 .<br />

Karch and Lasagna 9 and the Food and Drug<br />

Administration (FDA) 10 .<br />

WHO<br />

Any response to a drug which is noxious and<br />

unintended, and which occurs at doses<br />

normally used in man for prophylaxis,<br />

diagnosis, or therapy of disease, or for the<br />

modification of physiological function.<br />

Karch and Lasagna<br />

Any response to a drug that is noxious and<br />

unintended, and that occurs at doses used in<br />

humans for prophylaxis, diagnosis, or therapy,<br />

excluding failure to accomplish the intended<br />

purpose.<br />

FDA<br />

For reporting purposes, FDA categorizes a<br />

serious adverse event (events relating to drugs or<br />

devices) as one in which “the patient outcome<br />

is death, life-threatening (real risk of dying),<br />

hospitalization (initial or prolonged), disability<br />

(significant, persistent, or permanent),<br />

congenital anomaly, or required intervention<br />

to prevent permanent impairment or damage.<br />

Classification of Adverse Drug Reactions<br />

ADRs can be divided schematically into two<br />

major categories:<br />

606

IJRPC 2011, 1(3) Srinivasan et al. ISSN: 22312781<br />

Type A and Type B (Table 1).<br />

Type A reactions are common, predictable and<br />

may occur in any individual. Type B ADRs are<br />

uncommon and unpredictable and only occur<br />

in susceptible individuals 11 .<br />

Type A reactions are the most frequent and<br />

can be observed in as many as 25–45% of<br />

patients. These represent an exaggeration of<br />

the known primary and/or secondary<br />

pharmacological actions of the drug, they are<br />

dose related and could probably be avoided<br />

and/or foreseen 12 . Multi-factorial, involving<br />

not only defects at multiple gene loci but also<br />

environmental factors such as concomitant<br />

infections. Most work has focused on enzyme<br />

polymorphism in drug oxidation and<br />

conjugation as risk factors for drug toxicity but<br />

genes involved in cell repair mechanisms,<br />

elaboration of cytokines and immune<br />

responsiveness cannot be excluded to predict<br />

individual susceptibility to different forms of<br />

ADRs 12,14 . . Genetic polymorphisms are a<br />

source of variation of drug response in the<br />

human body. In relation to ADRs, most<br />

interest has centred on the involvement of<br />

pharmacokinetic factors and, in particular,<br />

drug metabolism. However, there is now<br />

increasing realization that genetic variation in<br />

drug targets (Pharmacodynamic factors) might<br />

also predispose to ADRs, although research<br />

into this area is in its infancy 15 .<br />

Mechanism by which ADR Occurs 16<br />

ADRs can be classified as either<br />

pharmacological reactions representing an<br />

augmentation of the known pharmacological<br />

actions of the drug or idiosyncratic reactions<br />

that are not predictable. Pharmacological<br />

reactions are most common, usually doserelated<br />

and are due to the primary or<br />

secondary pharmacological characteristics of<br />

the drug. Factors that predispose to these<br />

ADRs include dose, pharmaceutical variation<br />

in drug formulation, pharmacokinetic or<br />

pharmacodynamic abnormalities, and drugdrug<br />

interactions. Pharmacological ADRs<br />

occur when drug concentration in plasma or<br />

tissue exceeds the “therapeutic window” or<br />

when there is increased sensitivity to the drug<br />

(even in concentrations considered normal for<br />

the general population). Idiosyncratic ADRs<br />

are less common, often serious, not dose<br />

dependent and show no simple relationship<br />

between the dose and the occurrence of<br />

toxicity or the severity of the reaction. The<br />

toxic reactions may affect many organ systems<br />

either in isolation or combination. The<br />

mechanism of these is not clear but is thought<br />

to include receptor abnormality, abnormality<br />

of a biological system that is unmasked by the<br />

drug, immunological response, drug-drug<br />

interactions, or be multi-factorial.<br />

Adverse drug reaction (ADR) monitoring<br />

involves following steps<br />

1. Identifying adverse drug reaction<br />

(ADR).<br />

2. Assessing causality between drug and<br />

suspected reaction by using various<br />

algorithms.<br />

3. Documentation of ADR in patient’s<br />

medical records.<br />

4. Reporting serious ADRs to<br />

pharmacovigilance centres /ADR<br />

regulating authorities<br />

Identifying the Adverse Drug Reaction<br />

The ADRs produced by a certain new drug are<br />

often recognized when the medication is<br />

undergoing its phase three randomized<br />

controlled trials. Both in the USA and in the<br />

UK there is post marketing surveillance of<br />

ADRs. In the UK this involves reporting<br />

suspected ADRs to the Commission on<br />

Human Medicine using the yellow card<br />

system. In this system new or intensively<br />

monitored medicines should have all<br />

suspected ADRs reported and other medicines<br />

should have any suspected serious ADR<br />

reported. In spite of these mechanisms ADRs<br />

are vastly under reported, 17 and initial reports<br />

of adverse reactions to drugs have taken up to<br />

seven years for trends to begin to appear in the<br />

literature. Under reporting of ADRs is likely to<br />

be due to a number of reasons. Reporting is<br />

not mandatory to clinicians in the UK and so is<br />

likely to be forgotten about amongst the many<br />

other work pressures. A clinician may have<br />

problems recognizing the scenario as an ADR,<br />

because of the background symptoms of the<br />

patient’s original illness. Clinicians might also<br />

be wary of reporting an ADR, because of<br />

worries of inducing a complaint, even in this<br />

no blame culture NHS. It should be pointed<br />

out that the yellow card clearly states you do<br />

not need to be sure if it is or is not an ADR<br />

before you report it. In recognizing an ADR<br />

there are a number of important factors one is<br />

identifying those individuals in whom ADRs<br />

are most likely to occur. This includes the aged<br />

and the premature, those with liver<br />

607

IJRPC 2011, 1(3) Srinivasan et al. ISSN: 22312781<br />

Post marketing surveillance<br />

Post marketing surveillance can be done by<br />

different methods:<br />

Anecdotal reporting 18<br />

The majority of the first reports of ADR come<br />

through anecdotal reports from individual<br />

doctors when a patient has suffered some<br />

peculiar effect. Such anecdotal reports need to<br />

be verified by further studies and these<br />

sometimes fail to confirm problem.<br />

Intensive monitoring studies 19,24<br />

These studies provide systematic and detailed<br />

collection of data from well defined groups of<br />

inpatients .The surveillance was done by<br />

specially trained health care professionals who<br />

devote their full time efforts towards<br />

recording all the drugs administered and all<br />

the events, which might conceivably be drug<br />

induced. Subsequently, statistical screening for<br />

drug-event association may lead to special<br />

studies. Popular example for this methodology<br />

is Boston collaborative drug surveillance<br />

program.<br />

Spontaneous reporting system (SRS) 20<br />

It is the principal method used for monitoring<br />

the safety of marketed drugs. In UK, USA,<br />

India and Australia, the ADR monitoring<br />

programs in use are based on spontaneous<br />

reporting systems. In this system, clinicians<br />

encourage reporting any or all reactions that<br />

believe may be associated with drug use<br />

usually, attention is focused on new drugs and<br />

serious ADRs. The rationale for SRS is to<br />

generate signals of potential drug problems, to<br />

identify rare ADRs and theoretically to<br />

monitor continuously all drug used in a<br />

variety of real conditions from the time they<br />

are first marketed. 15<br />

Cohort studies (Prospective studies) 19<br />

In these studies, patients taking a particular<br />

drug are identified and events are then<br />

recorded. The weakness of this method is<br />

relatively small number patients likely to be<br />

studied, and the lack of suitable control group<br />

to assess the background incidence of any<br />

adverse events. Such studies are expensive<br />

and it.<br />

Case control studies (retrospective studies) 18<br />

In these studies, patients who present with<br />

symptoms or an illness that could be due to an<br />

adverse drug reaction are screened to see if<br />

they have taken the drug. The prevalence of<br />

drug taking in this group is then compared<br />

with the prevalence in a reference population<br />

who do not have the symptoms or illness. The<br />

case control study is thus suitable for<br />

determining whether the drug causes a given<br />

adverse event once there is some initial<br />

indication that it might. However, it is not a<br />

method for detecting completely new adverse<br />

reactions.<br />

Case cohort studies 18<br />

The case cohort study is a hybrid of<br />

prospective cohort study and retrospective<br />

case control study, Patients who present with<br />

symptoms or an illness that could be due to an<br />

adverse drug reaction are screened to see if<br />

they have taken the drug. The results are then<br />

compared with the incidence of the symptoms<br />

or illness in a prospective cohort of patients<br />

who are taking the drug.<br />

Record linkage 18<br />

The idea here is to bring together a variety of<br />

patient records like general practice records of<br />

illness events and general records of<br />

prescriptions. In this way it may be possible to<br />

match illness events with drugs prescribed. A<br />

specific example of the use of record linkage is<br />

the so called prescription event monitoring<br />

scheme in which all the prescriptions issued<br />

by selected parishioners for a particular drug<br />

are obtained from the prescription pricing<br />

authority. The prescribers are then asked to<br />

inform those running scheme of any events in<br />

the patients taking the drugs. This scheme is<br />

less expensive and time consuming than other<br />

surveillance methods<br />

Meta analysis 21<br />

Meta analysis is a quantitative analysis of two<br />

or more independent studies for the purpose<br />

of determining an overall effect and of<br />

describing reasons for variation in study<br />

results, is another potential tool for identifying<br />

ADRs and assessing drug safety.<br />

Use of population statistics 22<br />

Birth defect registers and cancer registers can<br />

be used If drug induced event is highly<br />

remarkable or very frequent. If suspicions are<br />

aroused then case control and observational<br />

cohort studies will be initiated.<br />

608

IJRPC 2011, 1(3) Srinivasan et al. ISSN: 22312781<br />

II. Causality Assessment Between Drug and<br />

Suspected reaction 23<br />

Causality assessment is the method by which<br />

the extent of relationship between a drug and<br />

a suspected reaction is established.<br />

It is often difficult to decide if an adverse<br />

clinical event is an ADR or due to<br />

deterioration in the primary condition.<br />

Furthermore, if it is an ADR, which medicine<br />

caused it, as many patients are on multiple<br />

new medications when ill, particularly if<br />

admitted to hospital. In spite of these<br />

problems, the decision that a particular drug<br />

caused an ADR is usually based on clinical<br />

judgment alone. Studies have shown that there<br />

is a lot of variation in between rater and<br />

within rater decisions on causality of ADRs;<br />

this applies both to pharmacologists and<br />

physicians 25,26 .<br />

There are various approaches in the first<br />

approach an individual who is an expert in<br />

the area of ADRs would evaluate the case. In<br />

the process of evaluation, he or she may<br />

consider and critically evaluate all the data<br />

obtained to assess whether the drug has<br />

caused the particular reaction. A panel of<br />

experts adopts a similar procedure to arrive at<br />

a collective opinion. using algorithms<br />

including standardization of methods.<br />

Algorithms being structured systems<br />

specifically designed for the identification of<br />

an ADR, should theoretically make a more<br />

objective decision on causality. As such<br />

algorithms should have a better between and<br />

within rater agreement than clinical judgment.<br />

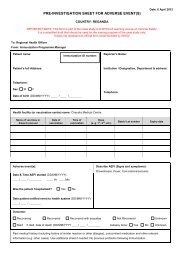

A number of algorithms or decision aids have<br />

been published including the Jones’<br />

algorithm, 28 the Naranjo algorithm, 27 the<br />

Yalealgorithm, 29 the Karch algorithm, 30 the<br />

Begaud algorithm, 31 the ADRAC, 32 the WHO-<br />

UMC, 33 and a newer quantitative approach<br />

Algorithm.34 Each of these algorithms has<br />

similarities and differences. And the most<br />

commonly used algorithms; the Naranjo<br />

algorithm (Fig :1) is shown below<br />

The Naranjo Algorithm is a questionnaire<br />

designed by Naranjo et al for determining the<br />

likelihood of whether an ADR (adverse drug<br />

reaction) is actually due to the drug rather<br />

than the result of other factors. Probability is<br />

assigned via a score termed definite, probable,<br />

possible or doubtful. Values obtained from the<br />

algorithm are sometimes used in peer reviews<br />

to verify the validity of author’s conclusions<br />

regarding adverse drug reactions. It is also<br />

called the Naranjo Scale or Naranjo Score.<br />

III. Documentation of ADRs in Patient’s<br />

Medical Records<br />

This aids as reference for alerting clinicians<br />

and other health care professionals to the<br />

possibility of a particular drug causing<br />

suspected reaction.<br />

IV. Reporting Serious ADRs to<br />

Pharmacovigilance Centres / ADR<br />

Regulating Authorities<br />

According to FDA, a serious reaction is<br />

classified as one which is fatal, life threatening,<br />

prolonging hospitalisation, and causing a<br />

significant persistent disability, resulting in a<br />

congenital anomaly and requiring intervention<br />

to prevent permanent damage or resulting in<br />

death 35 Hatwig SC, Seigel J and Schneider PJ<br />

categorised ADRs into seven levels as per their<br />

severity. Level 1&2 fall under mild category<br />

whereas level 3& 4 under moderate and level<br />

5, 6&7 fall under severe category . 36 (fig:2). Karch<br />

and Lasanga classify severity into minor,<br />

moderate, severe and lethal. In minor severity,<br />

there is no need of antidote, therapy or<br />

prolongation of hospitalisation. To classify as<br />

moderate severity, a change in drug therapy,<br />

specific treatment or an increase in<br />

hospitalization by at least one day is required.<br />

Severe class includes all potentially life<br />

threatening reactions causing permanent<br />

damage or requiring intensive medical care.<br />

Lethal reactions are the one which directly or<br />

indirectly contributes to death of the patient.<br />

Different ADR regulatory authorities are -<br />

Committee on safety of medicine (CSM),<br />

Adverse drug reaction advisory committee<br />

(ADRAC), 37 MEDWATCH, Vaccine Adverse<br />

Event Reporting System 38 WHO-UMC<br />

international database maintains all the data of<br />

ADRs.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

India has more than half a million qualified<br />

doctors and 15,000 hospitals having bed<br />

strength of 6, 24,000. It is the fourth largest<br />

producer of pharmaceuticals in the world. It is<br />

emerging as important clinical trial hub in the<br />

world. Many new drugs are being introduced<br />

every year and so every health care<br />

professional must have knowledge about<br />

importance of ADR monitoring and<br />

pharmacovigilance. Every health care<br />

professional should see it as a part of his/her<br />

professional duty keeping in mind about<br />

Hippocrates admonition” at least does no<br />

harm”.<br />

609

IJRPC 2011, 1(3) Srinivasan et al. ISSN: 22312781<br />

Table 1: Characteristics of Type A and Type B Adverse Reactions<br />

Characteristics Type A Type B<br />

Dose dependency Usually shows good relationship No simple relation ship<br />

Predictable from<br />

known pharmacology<br />

Yes<br />

Not usually<br />

Host factors Genetic factors might be important<br />

Dependent on host<br />

factors<br />

Frequency Common Uncommon<br />

Severity<br />

Variable but usually mild<br />

Variable,<br />

proportionately more<br />

severe<br />

Clinical burden High morbidity and low mortality<br />

High morbidity and<br />

mortality<br />

Overall portion of<br />

adverse drug reaction<br />

80% 20%<br />

First detection<br />

Phase1-III<br />

Phase IV, occasionally<br />

phase III<br />

Animal models Usually reproducible in animals<br />

No known animal<br />

models<br />

Level 1<br />

Level 2<br />

Level 3<br />

Level 4<br />

Level 5<br />

Level 6<br />

Level 7<br />

Table 2: Hartwig’s Severity Assessment Scale<br />

An ADR occurred but required no change in treatment with the suspected drug.<br />

The ADR required that treatment with the suspected drug be held, discontinued, or otherwise<br />

changed. No antidote or other treatment requirement was required. No increase in length of stay<br />

(LOS)<br />

The ADR required that treatment with the suspected drug be held, discontinued, or otherwise<br />

changed.<br />

AND/OR<br />

An Antidote or other treatment was required. No increase in length of stay (LOS)<br />

Mild= level 1 and 2, moderate= level 3 and 4, severe= 5, 6 and 7.<br />

Any level 3 ADR which increases length of stay by at least 1 day . OR<br />

The ADR was the reason for the admission<br />

Any level 4 ADR which requires intensive medical care<br />

The adverse reaction caused permanent harm to the patient<br />

The adverse reaction either directly or indirectly led to the death of the patient<br />

1) Are there previous conclusive reports of this reaction?<br />

If YES = +1, NO = 0, Do not know or not done = 0<br />

2) Did the adverse event appear after the suspected drug was Given?<br />

If YES = +2, NO = -1, Do not know or not done = 0<br />

3) Did the adverse reaction improve when the drug was discontinued or a specific antagonist was given?<br />

If YES = +1, NO = 0, Do not know or not done = 0<br />

4) Did the adverse reaction appear when the drug was Re-administered?<br />

If YES = +2, NO = -2, Do not know or not done = 0<br />

5) Are there alternative causes that could have caused the reaction?<br />

If YES = -1, NO = +2, Do not know or not done = 0<br />

6) Did the reaction reappear when a placebo was given?<br />

If YES = -1, NO = +1, Do not know or not done = 0<br />

7) Was the drug detected in any body fluid in toxic Concentrations?<br />

If YES = +1, NO = 0, Do not know or not done = 0<br />

610

IJRPC 2011, 1(3) Srinivasan et al. ISSN: 22312781<br />

8) Was the reaction more severe when the dose was increased or less severe when the dose was decreased?<br />

If YES = +1, NO = 0, Do not know or not done = 0<br />

9) Did the patient have a similar reaction to the same or similar drugs in any previous exposure?<br />

If YES = +1, NO = 0, Do not know or not done = 0<br />

10) Was the adverse event confirmed by any objective evidence?<br />

If YES = +1, NO = 0, Do not know or not done = 0<br />

SCORING<br />

9 = DEFINITE ADR, 5-8 = PROBABLE ADR,<br />

1-4 = POSSIBLE ADR , 0 = DOUBTFUL ADR<br />

Fig. 1: Naranjo Algorithm.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. Ditto AM. Drug allergy. In Grammer<br />

LC, Greenberger PA, editors.<br />

Patterson’s allergic diseases. 6th ed.;<br />

Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &<br />

Wilkins. 2002;295.<br />

2. Onder G, Pedone C, Landi F, Cesari<br />

M, Della VC and Bernabei R. Adverse<br />

Drug Reactions as Cause of Hospital<br />

Admissions Results from the Italian<br />

Group of Pharmacoepidemiology in<br />

the Elderly (GIFA). J Am Geriatr Soc.<br />

2002;50(12):1962-1968.<br />

3. Brown SD and Landry FJ. Recognizing<br />

Reporting and Reducing Adverse<br />

Drug Reactions. Southern Medical<br />

Journal. 2001;94:370-372.<br />

4. Murphy BM and Frigo LC.<br />

Development, Implementation and<br />

Results of a Successful<br />

Multidisciplinary Adverse Drug<br />

Reaction Reporting Program in a<br />

University Teaching Hospital.<br />

Hospital Pharmacy.1993;28:1199-1204.<br />

5. Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH and Corey<br />

PN. Incidence of Adverse Drug<br />

Reactions in Hospitalized Patients. A<br />

Meta analysis of Prospective Studies.<br />

Journal of American medical<br />

Association. 1998;279(15):1200-1205.<br />

6. David WB, Nathan S, David JC.<br />

Elisabeth B, Nan L, Laura A and<br />

Petersen . The Cotrst of Adverse Drug<br />

Events in Hospitalized Patients.<br />

Journal of American Medical<br />

Association. 1997;277(4):307-311<br />

7. Bordet S, Gautier H, Lelouet B and<br />

Dupuis J. Caron. Analysis of the Direct<br />

Cost of Adverse Drug Reaction in<br />

Hospitalised Patients. European<br />

Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.<br />

2001; 56:935-39.<br />

8. Requirements for adverse reaction<br />

reporting. Geneva, Switzerland:<br />

World Health Organization.1975.<br />

9. Karch FE, Lasagna L. Adverse drug<br />

reactions. A Critical<br />

Review.JAMA.1975; 234:1236–41.<br />

10. Kessler DA. Introducing MedWatch,<br />

using FDA for 3500. A New Approach<br />

to Reporting Medication and Device<br />

Adverse Effects and Product<br />

problems. JAMA.1993;269:2765–68.<br />

11. Pirmohamed M and Park BK. Genetic<br />

Susceptibility to Adverse Drug<br />

Reactions. Trends Pharmacol Sci.<br />

2001;22:298–305.<br />

12. Moore N. The role of the Clinical<br />

Pharmacologist in the Management of<br />

Adverse Drug Reactions. Drug Safety<br />

2001;24:1–7.<br />

13. Knowles SR, Uetrecht J and Shear NH.<br />

Idiosyncratic Drug Reactions. The<br />

reactive Metabolite Syndromes.<br />

Lancet. 2000;356:1587–91.<br />

14. Pirmohamed M, Breckenridge AM,<br />

Kitteringham NR and Park BK.<br />

Adverse drug Reactions. BMJ.<br />

1998;316:1295–98.<br />

15. Alvarado I, Wong ML and Licinio J.<br />

Advances in the Pharmacogenomics of<br />

Adverse Reactions. Pharmacogenom J.<br />

2002;2:273.<br />

611

IJRPC 2011, 1(3) Srinivasan et al. ISSN: 22312781<br />

16. Mann R and Andrews E.<br />

Pharmacovigilance. Chichester<br />

England: John Wiley and Sons Ltd;<br />

2002.<br />

17. Laepe LL, Brennan TA and Laird N.<br />

The Nature of Adverse Events in<br />

Hospitalized Patients. Results of the<br />

Harvard Medical Practice Study II.<br />

New Engl. J Med. 1991;324:377–84.<br />

18. Graham smith DG and Ransom JK.<br />

Adverse Drug Reactions to Drugs.<br />

Oxford Text Book of Clinical<br />

Pharmacology and Drug Therapy.3rd<br />

ed. Oxford university press. 202: 101-<br />

104.<br />

19. Lee B and Turner MW. Food and Drug<br />

Administrations Adverse Drug<br />

Reaction Monitoring Program.<br />

American Journal of Hospital<br />

Pharmacy. 1978; 35: 828-832.<br />

20. MC Nell JJ, Gash EA and Mcdonald<br />

MM. Post Marketing Surveillance<br />

Strengths and Limitations. The<br />

Medical Journal of Australia.<br />

1999;170:270-273.<br />

21. Brewer T and Colditz GA. Post<br />

Marketing Surveillance and Adverse<br />

Drug Reactions. Current Prospective<br />

and needs. Journal of American<br />

Medical Association. 1999;281: 824-<br />

829.<br />

22. Laurence DR, Bennett PN and Browm<br />

MJ. Unwanted Effects and Adverse<br />

Drug Reactions. Clinical<br />

Pharmacology. Eighth ed. Churchill<br />

Livingston.1998;121-137.<br />

23. Edwards IR and Aronson JK. Adverse<br />

Drug Reactions. Definition Diagnosis<br />

and Management. Lancet. 356: 1255-59<br />

24. Hurwitz N and Wade O.L. Intensive<br />

Monitoring of Adverse Drug<br />

Reactions to Drugs. British Medical<br />

Journal. 1969;1:531-536.<br />

25. Blanc S, Leuenberger P, Berger JP,<br />

Brooke M and Schelling JL.<br />

Judgements of Trainedobservers on<br />

Adverse Drug Reactions. Clin<br />

Pharmacol Ther. 1979;25:493–98.<br />

26. Karsh FE, Smith CL, Kerzner B,<br />

Mazzullo JM, Weintraub M and<br />

Lasanga L. Adverse Drug Reactions. A<br />

Matter of Opinion. Clin Pharmacol<br />

Ther. 1976;19:489–92.<br />

27. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellars EM,<br />

Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA and<br />

Janecek E. Method for Estimating the<br />

Probability of Adverse Drug<br />

Reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther.<br />

1981;30:239–45.<br />

28. Jones JK. Adverse Drug Reactions in<br />

the Community Health Setting.<br />

Approach to Recognizing, Counseling<br />

and Reporting. Fam Community<br />

Health. 1982;5(2):58–67.<br />

29. Kramer MS and Hutchinson TA. The<br />

Yale algorithm. Special workshopclinical.<br />

Drug Inf J. 1984;18:283–91.<br />

30. Karch FE and Lasagna L. Towards the<br />

Operational Identification of Adverse<br />

Drug Reaction. Clin Pharmacol Ther.<br />

1977;21:247–54.<br />

31. Begaud B, Evreux JC, Jouglard J and<br />

Lagier G. Imputation of the<br />

Unexpected or Toxic Effects of Drugs.<br />

Actualisation of the Methods Used in<br />

France. Therapie.1985;40:115–18.<br />

32. Mashford MI. The Australian Method<br />

of Drug Event Assessment. Drug Inf J.<br />

1984;18:271–73.<br />

33. WHO-UMC causality assessment<br />

system. Available from<br />

.<br />

34. Koh Y, Chu WY and Shu CL. A<br />

Quantitative Approach Using Genetic<br />

Algorithm in Designing a Probability<br />

Scoring System of an Adverse Drug<br />

Reaction Assessment System. Int J<br />

Med Inf. 2008;77:421–30.<br />

35. Hubes ML, Whittlesea CMC and<br />

Lusconbe DK. Symptoms or Adverse<br />

Reaction. An Investigation into How<br />

Symptoms are Recognized as Side<br />

Effects of Medication. Pharmacy<br />

journal. 2002;269:719-722.<br />

36. Hartwig SC, Siegel J and Schneider PJ.<br />

Preventability and Severity<br />

Assessment in Reporting Adverse<br />

Drug reactions. American Journal of<br />

Hospital Pharmacy. 1992;49:2229-31<br />

37. Information About Adverse Drug<br />

Reaction Advisory Committee<br />

(Available<br />

from<br />

URL:http//www.helth.gov.av/tga/a<br />

dr/adrfaq.htm<br />

38. Information About Vaccine Adverse<br />

Event Reporting System (Available<br />

from URL:http//www.vaers.org).<br />

612