American magazine: March 2017

In this issue, read a love letter (or 26) to Washington, DC; delve into the long and colorful history of the polygraph; get to know the likable curmudgeon of Capitol Hill Books; and meet AU’s 15th president, Sylvia Mathews Burwell. Also, brush up on World War I history, peek into an archeologist’s bag, hop on the Metro to Farragut West, and get to know two of AU’s 643 Twin Cities transplants.

In this issue, read a love letter (or 26) to Washington, DC; delve into the long and colorful history of the polygraph; get to know the likable curmudgeon of Capitol Hill Books; and meet AU’s 15th president, Sylvia Mathews Burwell. Also, brush up on World War I history, peek into an archeologist’s bag, hop on the Metro to Farragut West, and get to know two of AU’s 643 Twin Cities transplants.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Product<br />

of the System<br />

By Mike Unger<br />

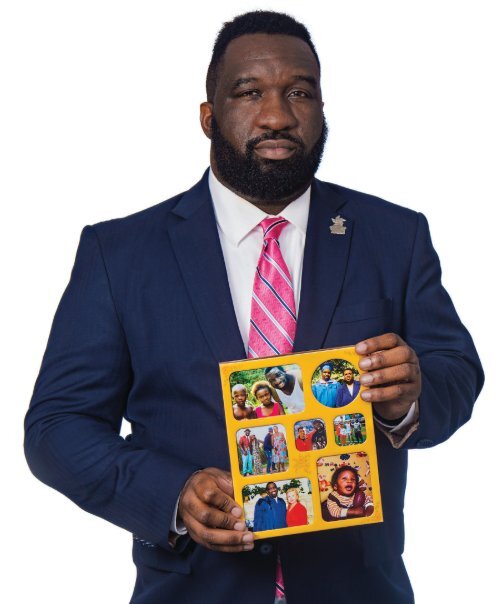

Jelani Freeman entered foster care at eight years old.<br />

While in one sense he never got out, it never got him.<br />

During a trip to Haiti sponsored by<br />

the Congressional Coalition on<br />

Adoption Institute last summer,<br />

Jelani Freeman, CAS/MA ’07, had an<br />

epiphany. Among the politicians, staffers,<br />

practitioners, and advocates in the delegation<br />

was a scientist who specialized in early<br />

childhood brain development. At one point<br />

during the tour, which included stops at<br />

several orphanages sanitized for the<br />

dignitaries’ visit but still heartbreaking<br />

in their squalor, he mentioned to Freeman<br />

how imperative a child’s first<br />

three years are to a lifetime of<br />

cognitive advancement.<br />

“I realized for the first time<br />

that with all the shortcomings<br />

that my mom had, she did a lot<br />

for me, because if she didn’t read<br />

to me or talk to me, I wouldn’t<br />

be where I am now,” Freeman,<br />

36, says. “It made me think, wow,<br />

maybe there was something good<br />

during my childhood.”<br />

Twenty-eight years ago<br />

Freeman came home from<br />

elementary school to find the<br />

small, single-family house his mother rented<br />

in a rough section of Rochester, New York,<br />

empty. No one was there to ask, “What did<br />

you learn today?” or, “Do you want meatloaf<br />

or mac and cheese for dinner?”<br />

The only sound was silence.<br />

This was not particularly strange—often<br />

his mother disappeared for days at a time,<br />

leaving young Jelani to fend for himself. He<br />

learned to mop the floors and scrub toilets,<br />

and even became a halfway decent cook.<br />

Chicken and rice was a specialty. His older<br />

brother and sister had moved out long<br />

ago, and his father, whom he has never<br />

met, was in prison, serving a sentence for<br />

attempted murder.<br />

Vanessa Freeman battled mental health<br />

issues for much of her life, which sometimes<br />

left her bedridden or barricaded in her<br />

room. She struggled to hold down a job or<br />

It was only when, later<br />

that night, an adult walked<br />

through the front door<br />

that he knew his life would<br />

never be the same. That<br />

grown-up wasn’t his mom;<br />

it was a social worker.<br />

create a semblance of normalcy at home for<br />

Jelani, who somehow never got angry or<br />

disillusioned with her. She was his mother;<br />

he loved her.<br />

When he returned home from school the<br />

next day, again to a deserted house, Freeman<br />

still didn’t worry. It was only when, later that<br />

night, an adult walked through the front door<br />

that he knew his life would never be the<br />

same. That grown-up wasn’t his mom;<br />

it was a social worker.<br />

At eight years old, Freeman entered the<br />

foster care system, and while in one sense<br />

he never got out, it never got him. Somehow,<br />

while he trudged from one foster home to<br />

another using “a trash bag as my suitcase,” as<br />

he told the world in July during his speech<br />

at the Democratic National Convention in<br />

Philadelphia, he managed to forge his own<br />

path forward.<br />

Despite the hardships and<br />

heartaches he faced, pain that<br />

often proves too deeply rooted for<br />

thousands of kids in the foster care<br />

system to ever shed, something<br />

good did indeed emerge from<br />

Jelani Freeman’s childhood—<br />

Jelani Freeman himself.<br />

“I and I was protective<br />

was really ashamed of<br />

being in foster care,<br />

of my mom,” says Freeman, who<br />

recounts details of his childhood<br />

with an outward detachment. “I remember in<br />

college I didn’t speak to people much about<br />

it. I [thought] I was going to become a history<br />

teacher, get married, have kids and have a<br />

house, and everything that happened with me<br />

would be behind me and I’d never talk about<br />

it. I quickly learned that’s just not how it’s<br />

going to be. When I came to DC, I started to<br />

FOLLOW US @AU_AMERICANMAG 25