Java.Oct.2017

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

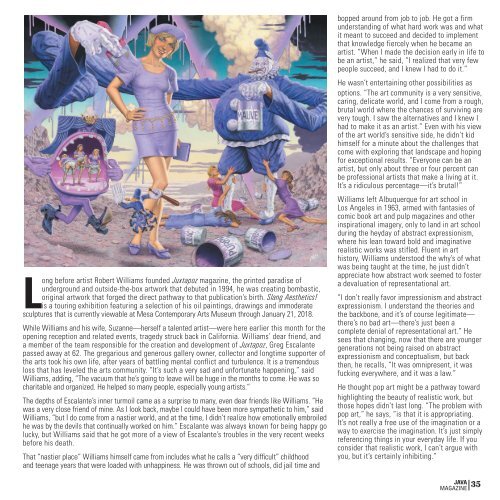

Long before artist Robert Williams founded Juxtapoz magazine, the printed paradise of<br />

underground and outside-the-box artwork that debuted in 1994, he was creating bombastic,<br />

original artwork that forged the direct pathway to that publication’s birth. Slang Aesthetics!<br />

is a touring exhibition featuring a selection of his oil paintings, drawings and immoderate<br />

sculptures that is currently viewable at Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum through January 21, 2018.<br />

While Williams and his wife, Suzanne—herself a talented artist—were here earlier this month for the<br />

opening reception and related events, tragedy struck back in California. Williams’ dear friend, and<br />

a member of the team responsible for the creation and development of Juxtapoz, Greg Escalante<br />

passed away at 62. The gregarious and generous gallery owner, collector and longtime supporter of<br />

the arts took his own life, after years of battling mental conflict and turbulence. It is a tremendous<br />

loss that has leveled the arts community. “It’s such a very sad and unfortunate happening,” said<br />

Williams, adding, “The vacuum that he’s going to leave will be huge in the months to come. He was so<br />

charitable and organized. He helped so many people, especially young artists.”<br />

The depths of Escalante’s inner turmoil came as a surprise to many, even dear friends like Williams. “He<br />

was a very close friend of mine. As I look back, maybe I could have been more sympathetic to him,” said<br />

Williams, “but I do come from a nastier world, and at the time, I didn’t realize how emotionally embroiled<br />

he was by the devils that continually worked on him.” Escalante was always known for being happy go<br />

lucky, but Williams said that he got more of a view of Escalante’s troubles in the very recent weeks<br />

before his death.<br />

That “nastier place” Williams himself came from includes what he calls a “very difficult” childhood<br />

and teenage years that were loaded with unhappiness. He was thrown out of schools, did jail time and<br />

bopped around from job to job. He got a firm<br />

understanding of what hard work was and what<br />

it meant to succeed and decided to implement<br />

that knowledge fiercely when he became an<br />

artist. “When I made the decision early in life to<br />

be an artist,” he said, “I realized that very few<br />

people succeed, and I knew I had to do it.”<br />

He wasn’t entertaining other possibilities as<br />

options. “The art community is a very sensitive,<br />

caring, delicate world, and I come from a rough,<br />

brutal world where the chances of surviving are<br />

very tough. I saw the alternatives and I knew I<br />

had to make it as an artist.” Even with his view<br />

of the art world’s sensitive side, he didn’t kid<br />

himself for a minute about the challenges that<br />

come with exploring that landscape and hoping<br />

for exceptional results. “Everyone can be an<br />

artist, but only about three or four percent can<br />

be professional artists that make a living at it.<br />

It’s a ridiculous percentage—it’s brutal!”<br />

Williams left Albuquerque for art school in<br />

Los Angeles in 1963, armed with fantasies of<br />

comic book art and pulp magazines and other<br />

inspirational imagery, only to land in art school<br />

during the heyday of abstract expressionism,<br />

where his lean toward bold and imaginative<br />

realistic works was stifled. Fluent in art<br />

history, Williams understood the why’s of what<br />

was being taught at the time, he just didn’t<br />

appreciate how abstract work seemed to foster<br />

a devaluation of representational art.<br />

“I don’t really favor impressionism and abstract<br />

expressionism. I understand the theories and<br />

the backbone, and it’s of course legitimate—<br />

there’s no bad art—there’s just been a<br />

complete denial of representational art.” He<br />

sees that changing, now that there are younger<br />

generations not being raised on abstract<br />

expressionism and conceptualism, but back<br />

then, he recalls, “It was omnipresent, it was<br />

fucking everywhere, and it was a law.”<br />

He thought pop art might be a pathway toward<br />

highlighting the beauty of realistic work, but<br />

those hopes didn’t last long. “The problem with<br />

pop art,” he says, “is that it is appropriating.<br />

It’s not really a free use of the imagination or a<br />

way to exercise the imagination. It’s just simply<br />

referencing things in your everyday life. If you<br />

consider that realistic work, I can’t argue with<br />

you, but it’s certainly inhibiting.”<br />

JAVA 35<br />

MAGAZINE