BookAction_issue1-2

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Book-Café<br />

The Barricade<br />

Voorstraat 71<br />

3512 AK, Utrecht<br />

Sun 16:00-23:00<br />

http://acu.nl<br />

barricade@acu.nl<br />

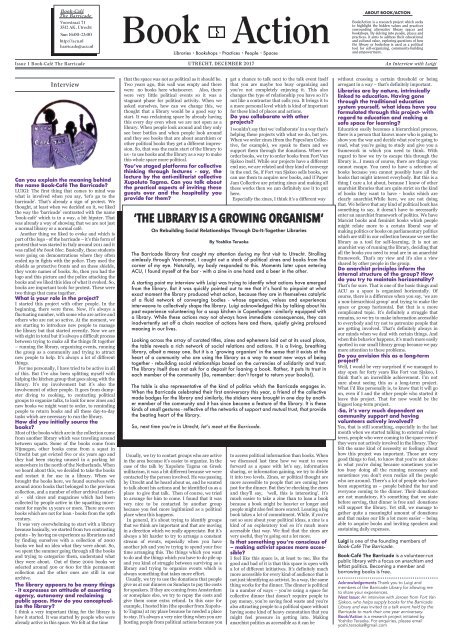

Issue 1 Book-Café The Barricade<br />

Libraries Bookshops Practices People Spaces<br />

UTRECHT, DECEMBER 2017<br />

ABOUT BOOK/ACTION<br />

Book/Action is a research project which seeks<br />

to highlight the hidden values and practices<br />

surrounding alternative library spaces and<br />

bookshops. By delving into people, places and<br />

practices, it aims to address their educational<br />

and cultural value, exploring questions of how<br />

the library or bookshop is used as a political<br />

tool for self-organizing, community-building<br />

and empowerment.<br />

An Interview with Luigi<br />

Interview<br />

Can you explain the meaning behind<br />

the name Book-Café The Barricade?<br />

LUIGI: The first thing that comes to mind was<br />

what is involved when you say, ‘let’s go to the<br />

barricade’. That's already a sign of protest. We<br />

thought, at least when we decided on it, we liked<br />

the way the ‘barricade’ contrasted with the name<br />

‘book-café’ which is in a way, a bit hipster. That<br />

was already a way of showing that we are not just<br />

a normal library or a normal café.<br />

Another thing we liked to evoke and which is<br />

part of the logo - of the barricade – it’s this form of<br />

protest that was started in Italy around 2011 and it<br />

was called the book bloc. Basically, these students<br />

were going on demonstrations where they often<br />

ended up in fights with the police. They used the<br />

shields as protective fronts and on these shields,<br />

they wrote names of books. So, then you had the<br />

logo and this picture and the police attacking the<br />

books and we liked this idea of what it evoked. So,<br />

books are important tools for protest. These were<br />

two things that came together.<br />

What is your role in the project?<br />

I started this project with other people. In the<br />

beginning, there were three. Now, it’s always a<br />

fluctuating number, with some who are active and<br />

others who are not so active. At the moment, we<br />

are starting to introduce new people to manage<br />

the library but that started recently. Now we are<br />

with eight in total but it’s always a difficult process<br />

between trying to make all the things fit together<br />

– running the library, organizing events, running<br />

the group as a community and trying to attract<br />

new people to help. It’s always a lot of different<br />

things.<br />

For me personally, I have tried to be active in all<br />

of this. But I’ve also been splitting myself with<br />

helping the kitchen group that goes along with the<br />

library. It’s my involvement but it’s also the<br />

involvement of other people. It goes from dumpster<br />

diving to cooking, to contacting political<br />

groups to organize talks, to look for new zines and<br />

new books we might want to order, to reminding<br />

people to return books and all these day-to-day<br />

tasks which are necessary to run the library.<br />

How did you initially source the<br />

books?<br />

Most of the books which are in the collection come<br />

from another library which was traveling around<br />

between squats. Some of the books come from<br />

Nijmegen, other books come from a squat in<br />

Utrecht but got evicted five or six years ago and<br />

they had been staying unused in a parking lot<br />

somewhere in the north of the Netherlands. When<br />

we heard about this, we decided to take the books<br />

and restart it for use in a library. When we<br />

brought the books here, we found ourselves with<br />

around 2000 books that belonged to the previous<br />

collection, and a number of other archival material<br />

- old zines and magazines which had been<br />

collected by people active in the squatting movement<br />

for maybe 15 years or more. There are even<br />

books which are not for loan - books from the 19th<br />

century.<br />

It was very overwhelming to start with a library<br />

because basically, we started from two contrasting<br />

points - by having no experience as librarians and<br />

by finding ourselves with a collection of 2000<br />

books we had no idea what they were about. So,<br />

we spent the summer going through all the books<br />

and trying to categorize them, understand what<br />

they were about. Out of these 2000 books we<br />

selected around 500 or 600 for this permanent<br />

collection and the other ones are still in our<br />

archive.<br />

The library appears to be many things<br />

- it expresses an attitude of asserting<br />

agency, autonomy and reclaiming<br />

public space. How do you conceptualize<br />

the library?<br />

I think a very important thing for the library is<br />

how it started. It was started by people who were<br />

already active in this space. We felt at the time<br />

that the space was not as political as it should be.<br />

Two years ago, this wall was empty and there<br />

were no books here whatsoever. Also, there<br />

were very little political events so it was a<br />

stagnant phase for political activity. When we<br />

asked ourselves, how can we change this, we<br />

thought that a library would be a good way to<br />

start. It was reclaiming space by already having<br />

this every day even when we are not open as a<br />

library. When people look around and they only<br />

see beer bottles and when people look around<br />

and they see books that are about anarchism or<br />

other political books they get a different impression.<br />

So, that was the main start of the library to<br />

us - to use books and the library as a way to make<br />

this whole space more political.<br />

You’ve staged platforms for collective<br />

thinking through lectures - say, the<br />

lecture by the anti-militarist collective<br />

Xupoluto Tagma. Can you talk about<br />

the practical aspects of inviting these<br />

guests over and the hospitality you<br />

provide for them?<br />

The Barricade library first caught my attention during my first visit to Utrecht. Strolling<br />

aimlessly through Voorstraat, I caught out a stack of political zines and books from the<br />

corner of my eye. Naturally, my body responded to this. Moments later upon entering<br />

ACU, I found myself at the bar - with a zine in one hand and a beer in the other.<br />

A starting point my interview with Luigi was trying to identify what actions have emerged<br />

from the library. But it was quickly pointed out to me that itʼs hard to pinpoint at what<br />

exact moment the library produced what action, because they are in themselves catalytic<br />

of a fluid network of converging bodies - whose agencies, values and experiences<br />

interweave to collectively shape the library. Luigi acknowledged this by talking about his<br />

past experience volunteering for a soup kitchen in Copenhagen - similarly equipped with<br />

a library. While these actions may not always have immediate consequences, they can<br />

inadvertently set off a chain reaction of actions here and there, quietly giving profound<br />

meaning in our lives.<br />

Looking across the array of curated titles, zines and ephemera laid out at its usual place,<br />

the table reveals a rich network of social relations and actions. It is a living, breathing<br />

library, albeit a messy one. But it is a ʻgrowing organismʼ in the sense that it exists at the<br />

heart of a community who are using the library as a way to enact new ways of being<br />

together - rebuilding social relationships based on the currencies of solidarity and trust.<br />

The library itself does not ask for a deposit for loaning a book. Rather, it puts its trust in<br />

each member of the community (So, remember: donʻt forget to return your books!).<br />

The table is also representative of the kind of politics which the Barricade engages in.<br />

When the Barricade celebrated their first anniversary this year, a friend of the collective<br />

made badges for the library and similarly, the stickers were brought in one day by another<br />

member of the community and it has since become a feature of the library. It is these<br />

kinds of small gestures - reflective of the networks of support and mutual trust, that provide<br />

the beating heart of the library.<br />

So, next time youʼre in Utrecht, letʼs meet at the Barricade.<br />

Usually, we try to contact groups who are active<br />

in the area because it’s easier to organize. In the<br />

case of the talk by Xupoluto Tagma on Greek<br />

militarism, it was a bit different because we were<br />

contacted by the person involved. He was passing<br />

by Utrecht and he heard about us, and he wanted<br />

to talk about his actions and he identified us as a<br />

place to give that talk. Then of course, we tried<br />

to arrange for him to come. I found that it was<br />

very nice to be contacted by another group<br />

because you feel more legitimized as a political<br />

place when this happens.<br />

In general, it’s about trying to identify groups<br />

that we think are important and that are moving<br />

in a direction which we really appreciate. But it’s<br />

always a bit harder to try to arrange a constant<br />

stream of events, especially when you have<br />

another job and you’re trying to spend your free<br />

time arranging this. The things which you want<br />

to do and the things which you have to do pile up<br />

and you kind of struggle between surviving as a<br />

library and trying to organize events which is<br />

always something that takes more effort.<br />

Usually, we try to use the donations that people<br />

give us at our dinners on Sundays to pay the costs<br />

for speakers. If they are coming from Amsterdam<br />

or someplace else, we try to repay the costs and<br />

give them some extra refund. In this case for<br />

example, I hosted him (the speaker from Xupoluto<br />

Tagma) at my place because he needed a place<br />

to stay. It’s always a very nice thing when you are<br />

hosting people from political actions because you<br />

get a chance to talk next to the talk event itself<br />

that you are maybe too busy organizing and<br />

you’re not completely enjoying it. This also<br />

changes the type of relationship you have so it’s<br />

not like a contractor that calls you. It brings it to<br />

a more personal level which is kind of important<br />

for these kind of places and actions.<br />

Do you collaborate with other<br />

projects?<br />

I wouldn’t say that we ‘collaborate’ in a way that's<br />

helping these projects with what we do, but yes.<br />

When we order zines (from the PaperJam Collective,<br />

for example), we speak to them and we<br />

support them through the donations. When we<br />

order books, we try to order books from Fort Van<br />

Sjakoo itself. While our projects have a different<br />

end use, we are related and they kind of converge<br />

in the end. So, if Fort van Sjakoo sells books, we<br />

can use them to acquire new books, and if Paper<br />

Jam Collective are printing zines and making all<br />

these works then we can definitely use it to put<br />

here.<br />

Especially the zines, I think it's a different way<br />

‘THE LIBRARY IS A GROWING ORGANISM’<br />

On Rebuilding Social Relationships Through Do-It-Together Libraries<br />

By Yoshiko Teraoka<br />

to access political information than books. When<br />

we discussed last time how we want to move<br />

forward as a space with let’s say, information<br />

sharing, or information gaining, we try to divide<br />

it into two levels. Zines, or political thought are<br />

more accessible to people that are coming here<br />

just for the dinner. But they’re checking the zines<br />

and they’ll say, ‘well, this is interesting’. It’s<br />

much easier to take a zine than to loan a book<br />

because a book might be heavier or longer and<br />

people might also feel more scared. Loaning a big<br />

book takes a lot of commitment. While, if you’re<br />

not so sure about your political ideas, a zine is a<br />

kind of an exploratory tool so it’s much more<br />

accessible that way. We find that the zines are<br />

very useful, they’re going out a lot more.<br />

Is that something you’re conscious of<br />

– making activist spaces more accessible?<br />

I feel like this space is, at least to me, like the<br />

good and bad of it is that this space is open with<br />

a lot of different initiatives. It's definitely much<br />

more accessible for every kind of audience that is<br />

not just identifying as activist. In a way, the same<br />

thing works for the dinner. The dinner is political<br />

in a number of ways – you’re using a space for<br />

collective dinner that doesn’t require people to<br />

pay money, you’re saving food waste and you’re<br />

also attracting people to a political space without<br />

having some kind of heavy connotation that you<br />

might feel pressure in getting into. Making<br />

anarchist politics as accessible as it can be<br />

without crossing a certain threshold or being<br />

arrogant in a way – that’s definitely important.<br />

Libraries are by nature, intrinsically<br />

linked to education. Having gone<br />

through the traditional education<br />

system yourself, what ideas have you<br />

formulated through this project- with<br />

regard to education and making a<br />

safe space for learning?<br />

Education easily becomes a hierarchical process,<br />

there is a person that knows more who is going to<br />

show you the way and decide what you’re going to<br />

read, what you’re going to study and give you a<br />

framework in which you need to think. With<br />

regard to how we try to escape this through the<br />

library is…I mean of course, there are things you<br />

cannot escape. You need to have a selection of<br />

books because you cannot possibly have all the<br />

books that might interest everybody. But this is a<br />

thing I care a lot about, because I know of other<br />

anarchist libraries that are quite strict on the kind<br />

of books they want to have - books which are<br />

clearly anarchist.While here, we are not doing<br />

that. We believe that any kind of political book has<br />

something to say, it doesn’t have to necessarily<br />

enter an anarchist framework of politics. We have<br />

Marxist books and feminist books which people<br />

might relate more to a certain liberal way of<br />

making politics or books on parliamentary politics<br />

which are still in our collection because we see the<br />

library as a tool for self-learning. It is not an<br />

anarchist way of running the library, deciding that<br />

all the books you need to read are in an anarchist<br />

framework. That’s my view and it’s also a view<br />

shared by other people in the group.<br />

Do anarchist principles inform the<br />

internal structure of the group? How<br />

do you try to maintain horizontality?<br />

That’s for sure. That is one of the basic things and<br />

ACU as a space is organized horizontally. Of<br />

course, there is a difference when you say, ‘we are<br />

a non-hierarchical group’ and trying to make the<br />

space or group horizontal. But that is a more<br />

complicated topic. It’s definitely a struggle that<br />

remains, so we try to make information accessible<br />

to everybody and try not to patronize people that<br />

are getting involved. That’s definitely always in<br />

our minds when we deal with certain things. And<br />

when this behavior happens, it’s much more easily<br />

spotted in our small library group because we pay<br />

more attention to these problems.<br />

Do you envision this as a long-term<br />

project?<br />

Well, I would be very surprised if we managed to<br />

stay open for forty years like Fort van Sjakoo, I<br />

think that’s an incredible achievement. I’m not<br />

sure about seeing this as a long-term project.<br />

What I’d like personally is, to know that it will go<br />

on, even if I and the other people who started it<br />

leave this project. That for now would be the<br />

biggest long-term project.<br />

-So, it’s very much dependent on<br />

community support and having<br />

volunteers actively involved?<br />

Yes, that is still something, especially in the last<br />

month when we started talking to external volunteers,<br />

people who were coming to the space even if<br />

they were not actively involved in the library. They<br />

felt the same kind of necessity or feelings about<br />

how this project was important. Those are very<br />

good things to feel, to know that you’re not alone<br />

in what you’re doing because sometimes you’re<br />

too busy doing all the running necessary and<br />

sometimes you don’t even realize all the people<br />

who are around. There’s a lot of people who have<br />

been supporting us – people behind the bar and<br />

everyone coming to the dinner. Their donations<br />

are not mandatory, it’s something that we state<br />

before serving, that dinner is free and donations<br />

will support the library. Yet still, we manage to<br />

gather quite a meaningful amount of donations<br />

and that makes our life a lot more easier – being<br />

able to acquire books and inviting speakers and<br />

sustaining daily expenses.<br />

Luigi is one of the founding members of<br />

Book-Café The Barricade.<br />

Book-Café The Barricade is a volunteer-run<br />

public library with a focus on anarchism and<br />

leftist politics. Becoming a member and<br />

borrowing books is free.<br />

Acknowledgements Thank you to Luigi and<br />

members of the Barricade Library for allowing me<br />

to share your experiences.<br />

Next Issue: An interview with Jeroen from Fort Van<br />

Sjakoo, who helps supply books for the Barricade<br />

Library and was invited to a talk event held by the<br />

Barricade to mark their one year anniversary.<br />

Book/Action is a research project initiated by<br />

Yoshiko Teraoka. For enquiries, please email<br />

yoshi.teraoka@gmail.com

VOORSTRAAT 71, 3512 AK UTRECHT<br />

BOOK-CAFÉ THE BARRICADE IS A VOLUNTEER-RUN PUBLIC LIBRARY LOCATED<br />

INSIDE ACU - A POLITICAL-CULTURAL CENTRE IN UTRECHT. WITH A FOCUS ON<br />

ANARCHISM AND LEFTIST POLITICS, THE PERMANENT COLLECTION HOUSES<br />

TOPICS RANGING FROM FEMINISM, MARXISM, DECOLONIALISM, ENVIRONMEN-<br />

TALISM, VEGANISM, SQUATTING TO DIY CULTURE. ON SUNDAYS, THE LIBRARY<br />

SERVES AS A PLATFORM FOR VARIOUS ACTIVITIES - FROM WORKSHOPS TO<br />

DISCUSSIONS, LECTURES ON CURRENT POLITICAL ISSUES, FOLLOWED BY A<br />

VEGAN DINNER OFFERED BY THE BARRICOONS KITCHEN - AN UTRECHT-BASED<br />

ANTIFOOD WASTE COLLECTIVE INSPIRED BY RACCOONS.

Het Fort van Sjakoo<br />

Jodenbreestraat 24 1011 NK, Amsterdam<br />

Mon-Fri 11:00-18:00, Sat 11:00-17:00<br />

http://www.sjakoo.nl info@sjakoo.nl<br />

(+31) 020- 625 89 79<br />

Issue 2 Het Fort Van Sjakoo<br />

Libraries Bookshops Practices People Spaces<br />

AMSTERDAM, JANUARY 2018<br />

ABOUT BOOK/ACTION<br />

Book/Action is a research project which seeks to highlight<br />

the hidden values and practices surrounding alternative<br />

library spaces and bookshops. By delving into people, places<br />

and practices, it aims to address their educational and<br />

cultural value, exploring questions of how the library or<br />

bookshop is used as a political tool for self-organizing,<br />

community-building and empowerment.<br />

An Interview with Jeroen<br />

Het Fort Van Sjakoo<br />

RADICAL BOOKSHOPS are a rarity these days. Itʼs<br />

particularly rare to come across an anarchist<br />

bookshop that enacts (or at least, attempts to) the<br />

very same principles it seeks to realize, without<br />

compromise. One such example is Het Fort Van<br />

Sjakoo, a not-for-profit and collectively run<br />

bookshop located in Amsterdam. The collective -<br />

with the help and support of their community, have<br />

been resiliently shaping their own economy and<br />

politics in the heart of the city for forty years.<br />

For some, the Fort is a remnant of the past - a time<br />

when political activism was still going strong on in<br />

the streets of Amsterdam. But to avoid romanticizing<br />

the past, which can often negate what we can learn<br />

from it, letʼs briefly stop to think about what itʼs<br />

doing today - not only in continuing to play a central<br />

role in the dissemination of radical and libertarian<br />

ideas, but how anarchist values of mutual-aid,<br />

reciprocity, common responsibility and cooperation<br />

are manifested in their praxis. This alone can help<br />

articulate what it might mean today to lead an<br />

ʻanti-capitalistʼ life. While capitalism likes to feed us<br />

the narrative that there is ʻno alternativeʼ, platforms<br />

like Fort van Sjakoo that experiment with self-management<br />

point to possibilities, that is with the participation<br />

and vision of everyone. For the anarcho-curious,<br />

perhaps we can begin to get a tangible glimpse<br />

of what this ʻalternativeʼ might look and feel like<br />

through the support and daily use of such<br />

bookshops.<br />

Itʼs impossible to provide a picture of their economic<br />

practice and organizational structure without first<br />

touching upon on their unique history. Volunteer<br />

Jeroen took me through an illuminating tour of the<br />

bookshop - from their origins, to their various<br />

struggles over the years, and what the bookshop<br />

stands for today.<br />

Interview<br />

What is your role in the bookshop?<br />

JEROEN: I do a lot of different things here. Because I<br />

find the function of our bookshop important, I’ve<br />

worked here for a very long time. I’ve worked here the<br />

longest out of all the people here-<br />

-30 years, right?<br />

Almost. I’ve worked here from December ’89 so that’s<br />

28 years, I think. So, that creates a lot of experience. My<br />

main focus is always to try to share all the knowledge<br />

and the responsibilities with fellow volunteers. I don’t<br />

really want to have a position that people think that I<br />

have more to say or that I would be more important,<br />

because I work here longer than they do. Maybe I do a<br />

lot, but everybody has the same say in the collective -<br />

which doesn’t mean that all the people do as much as<br />

some others.<br />

Through all the years of working here, there has<br />

always been like a core of people – 3 to 5 people who do<br />

a lot of stuff, whereas the collective has always been<br />

ranging from 9 to 15 persons. These 3-5 people do<br />

various things which are necessary for the shop:<br />

bookkeeping, reordering of sold material, IT-matters<br />

and organizing events. A group of people who take on<br />

less responsibilities limit their work to keeping the<br />

shop open. That has always been a kind of friction, or a<br />

thing that sometimes creates disappointment. When<br />

new people come into the collective as a volunteer, we<br />

always try to motivate them in taking on responsibilities<br />

because we are open to everything and to sharing.<br />

It’s up to the people who volunteer to put their interest<br />

into the work they do here -to really participate and to<br />

add content to the shop. Part of the things that we<br />

discuss during the meetings is the picking of the new<br />

titles. There’s the core people who almost always come<br />

to the bi-weekly meetings, but there’s quite a few<br />

volunteers who come once in a while or some never<br />

show up. That’s what we try – to share, take responsibility<br />

and do suggestions for stuff that we can distribute<br />

here which we think is important for people to<br />

know about.<br />

Specifically, about my role – I do a bit of everything,<br />

let’s say. But, what I like most is looking for new books.<br />

Because I, as one of the few people here - who speaks<br />

five languages (Spanish, French, German, Dutch and<br />

English), select a lot of publications in Spanish, French<br />

or German. I always try to follow fellow bookshops and<br />

publishers in other countries, to check which new<br />

books have been published and trying to get them here<br />

if they are relevant or interesting.<br />

I’m trying to understand the political and<br />

cultural landscape here in the Netherlands.<br />

Where does a radical bookshop<br />

like the Fort situate itself within the local<br />

community? And, what does it mean for<br />

this bookshop to occupy this street?<br />

The bookshop was started in October ’77 but this house<br />

was already squatted in ’75. In this neighborhood, the<br />

municipality had plans to erase most of the living<br />

spaces and make a big motorway through this part of<br />

the inner city - lined by hotels and office buildings.<br />

Also, there was the project of the construction of the<br />

metro. There was a<br />

lot of resistance in<br />

Amsterdam against<br />

those plans to<br />

eradicate the old<br />

n e i g h b o r -<br />

hoods,especially in<br />

this neighborhood<br />

which is called<br />

Nieuwmarkt<br />

(named after the<br />

market which is<br />

further in the<br />

direction of the<br />

central station).<br />

There was a lot of<br />

squatting in the<br />

early 70s already,<br />

the municipal<br />

government had<br />

planked a lot of old houses they wanted to demolish<br />

and squatters moved in and that was more or less the<br />

early days of the squatter movement. The Nieuwmarkt<br />

area was one of the first places where this started to<br />

flourish. There were hundreds of squats in the area<br />

and in the end, it has been partly won, partly lost. The<br />

metro has been built, but the motorway stops at the<br />

end of our street. It was planned to go straight to the<br />

central station, but nowadays it suddenly turns to the<br />

right and goes into the tunnel to the north of Amsterdam.<br />

What was also won was that this whole area has<br />

not been filled with office buildings. But social<br />

housing has come back, although in the last decade<br />

there’s a new tendency for the housing corporations to<br />

sell off quite a high percentage of the social housing<br />

which are older and use that money to act as state<br />

developers which is not really what their business<br />

should be. They should facilitate social housing and<br />

not luxury apartments.<br />

In 1977, some people in the neighborhood who were<br />

active in the activist scene had a lot of contacts with<br />

like-minded groups in Paris, London, Denmark,<br />

Berlin etc. They were exchanging information about<br />

common issues like city destruction and resistance in<br />

squatting. They thought, ‘we should do something<br />

with all the information’ and give that a platform<br />

where people can find stuff from abroad and other<br />

places in the Netherlands. So, a small group was<br />

formed and in October ‘77, they started the bookshop<br />

here in the squat. It has been run by volunteers since<br />

the beginning. We’ve never had paid members of the<br />

collective, which was a principle choice of us.<br />

At the end of the 80s, a lot of squats were legalized in<br />

Amsterdam and so, the people who lived upstairs and<br />

those who ran the bookshop started to pay a relatively<br />

low rent to a housing corporation, which in those days<br />

was still run by the municipal government.<br />

In 2002, the housing corporation had been privatized<br />

and like most, they started to raise the rents of all the<br />

business spaces they had in their possession. So they<br />

sent us a letter, proposing a rent raise of 900 percent<br />

and we thought, ‘we’re not accepting that.’ There was<br />

a big fuss and we tried to get in touch with them but<br />

they didn’t want to talk with us. We, together with<br />

supporters staged various actions. There was an<br />

occupation of their offices, their managing director<br />

was pied, one of their buildings was paintbombed from<br />

top to bottom. Then, they had a court case against us<br />

(not because of the actions but because of the rent<br />

dispute). In the end, they didn’t get the 900 percent<br />

rent raise that they were hoping to get. But, the judge<br />

decided that ‘only’ 400 percent was acceptable, which<br />

we still thought was unacceptable.<br />

Almost a year passed until that verdict. We thought,<br />

‘how are we going to do this?’. We didn’t have any<br />

guarantee because normally with a business space, you<br />

sign a renting contract for 5 years and after that, the<br />

landlord can establish a new rent for a new period of 5<br />

years. If they say the estate value of the business space<br />

has risen, then they are ‘obliged’ to raise the rent. So,<br />

if we would have signed a renting contract for another<br />

5 years, we would get this whole shit again. So, we<br />

thought, ‘how can we get out of this mouse trap<br />

situation?’- that every 5 years we would have like, a<br />

sword hanging above our heads. We said, ‘we want to<br />

buy the place,’ if they come up with an acceptable<br />

price. In the end, they offered us the place for 70<br />

percent of the (then) supposed market value, which<br />

was around 200,000 euros. We had one year to collect<br />

the money which we finally managed to do, with a lot<br />

of support from private people and legalized squats<br />

which had savings accounts for the maintenance of<br />

their building and they had some left-over money for<br />

the support of our cause. There were a lot of people<br />

who knew us from the past who spent 50-100 euros or<br />

more. We also sold bonds (in Dutch called an<br />

‘obligatie’) which is a piece of paper that says: ‘we owe<br />

you 50 euros’. These pieces of paper have a number<br />

and after 5 years, we start picking out ending numbers<br />

and then people with for example bonds with numbers<br />

ending on ‘5’ would get their money back. And so, we<br />

had from the 200 in total 225,000 euros that we had to<br />

pay. We had like 90,000 in gifts and the rest was in<br />

interest-free loans, which was really amazing. We didn’t<br />

have to use a bank whatsoever. We never thought that it<br />

was going to be such a success – that we could buy the<br />

place without having to pay a lot of interest to a bank or<br />

whatever shit institution. So, that gives a bit of an idea<br />

of the support that we have had in those days because a<br />

lot of them were older activists as well from the late 70s<br />

and 80s that spent a lot of money in gifts. If this would<br />

happen today, I don’t know if we would manage again to<br />

raise all that money because the former activists from<br />

the late 70s and 80s have become much older, their<br />

connection with us has for most become something<br />

from quite some time ago and some have died. However,<br />

we managed it in 2003 and at the moment, we try to be<br />

a platform for people in horizontal movements.<br />

Sometimes, we collaborate with places here in town or<br />

in other towns, like bookshops - these stores or distros<br />

we try to help. Some new people come in from time to<br />

time, sometimes in waves, like two years ago with all the<br />

student protests. There were a lot of students coming in,<br />

who had never seen the shop but because some of the<br />

students in the movement were more ‘radical’, and they<br />

told people, ‘if you’re interested in radical ideas, you<br />

should have a look here, they have a really nice and<br />

inspiring collection’.<br />

Can you talk about some of these<br />

collaborations with other initiatives?<br />

We sell zines by Paper Jam Collective which are always<br />

for sale for a donation price. They also do a lot of<br />

printing work for us lately. In the past, we always had a<br />

section with all kinds of pamphlets and we used to<br />

import them from all kinds of places but from time to<br />

time they turned out very expensive. So, what we did<br />

was try and find PDF files of those pamphlets and then<br />

we started to do the copying ourselves. If we couldn’t<br />

find a PDF we just kept an original and reproduced it.<br />

That we did for a long time ourselves, and Paper Jam<br />

offered us that if we have printing work they would be<br />

glad to do that. So lately, they are really stocking our<br />

shop. Because it’s a lot of work, you have to go to a<br />

printing shop and you have to stay there 3-4 hours at the<br />

photocopying machine, changing the sheets every time,<br />

and making the covers, and then afterwards you have to<br />

take them back, fold them and staple them. It’s really a<br />

lot of work. So, we’re very happy that they now do that<br />

for us.<br />

We also collaborate with Boekhandel Rosa in Groningen<br />

- one of the older radical bookshops which still<br />

remain together with us. They are very small - they<br />

mainly do secondhand books and they have a small<br />

section for new books. Since 20 years ago, we have been<br />

making a jointly published catalogue with them 3 or 4<br />

times a year. We take care of the new books section.<br />

There’s a secondhand section which is themed differently<br />

with each issue and Rosa puts in their selection. They<br />

order most of the non-Dutch new books through us<br />

because we do quite a lot of direct importing ourselves.<br />

Opstand in The Hague orders sometimes through us<br />

and the same accounts for the Anarchist Group in<br />

Nijmegen. We always offer fellow bookstores or distros,<br />

‘if you want to order stuff, you can order through us’ and<br />

we will order it with one of our own orders and they‘ll<br />

get it with almost the same discount as what we get. We<br />

have to get a small compensation for the shipping costs<br />

etc. That way, we try to expand the amount of places<br />

where people can get their stuff, because we think it’s a<br />

pity that there are so few places left where people can<br />

find their radical revolutionary information.<br />

The bookshop, as I understand, is a<br />

meeting point for various people such the<br />

activist community. Can you talk about<br />

how the bookshop functions?<br />

In different ways it’s a meeting place. It’s a place for<br />

coincidental meetings of people who are just visiting the<br />

bookshop and who meet each other – like people from<br />

abroad and people from the Netherlands. Sometimes,<br />

people from an anarchist group abroad and somebody<br />

from an anarchist group or another initiative from<br />

Amsterdam meet. We always have some maps of the city<br />

with alternative spaces, and we try to show people where<br />

they can find like-minded people and activists. Sometimes,<br />

we organize meetings which can be a presentation<br />

of a new book or it can be a theoretical discussion.<br />

About two years ago, we had a theoretical discussion on<br />

Anarchism and Revolution by Gabriel Kuhn, an Austrian<br />

anarchist writer based in Sweden. We thought maybe<br />

10 people would show up but 45 people turned up. On<br />

the other hand, sometimes we have a book presentation<br />

and we think, ‘this is really interesting!’ and only five<br />

people show up. It’s really unpredictable how much<br />

attention things attract.<br />

People from abroad who are traveling and staying a<br />

couple of days in Amsterdam – for example, to visit the<br />

International Institute of Social History, they<br />

sometimes like to do an event in Amsterdam and we try<br />

to organize something, either here or in the Anarchist<br />

Library. We organize things together sometimes.<br />

A lot of people who are new to the city and want to<br />

know something more about what is going on in town<br />

- drop in here, to have a chat and hear about places and<br />

things that are going on, for possibilities to become<br />

active in some kind of way.<br />

What is Fort van Sjakoo’s collective<br />

vision?<br />

It’s because we are a group of such different individuals<br />

with such different backgrounds, I can’t really give one<br />

description. We want to be a platform for all kinds of<br />

anti-authoritarian, horizontally-organized movements,<br />

ideas, people, to question authority, to question<br />

myths from our own movement that have been created<br />

through the time, be critical about our own ideas, and<br />

that's why we’re always trying to find new material<br />

from people criticizing previous thoughts or ideas.<br />

What is your personal vision?<br />

I try to give as much to the shop, the work that I do<br />

here and all the other volunteers is to get people<br />

motivated to do something, to change this world…<br />

maybe I sound like an old sod *laugh*.<br />

If I compare it to thirty years ago, there was a very<br />

thriving activist community in the Netherlands. There<br />

was a lot of direct action and it has almost vanished.<br />

Nowadays, it’s on a very small scale, it’s almost invisible.<br />

I would really like to see that flourish again and<br />

that people have some critical conscience.<br />

I earn my living with a job four days a week at a<br />

university bookshop. If I look around and see what<br />

young people are concerned about: they are not<br />

concerned about anything apart from their own egos,<br />

or their smartphones and their screen community.<br />

Even issues that are related to the university community<br />

and how things are being run over there, they are<br />

not interested at all, except for a very small minority<br />

who wants to question things and who wants to change<br />

things. I’m a bit pessimistic about that, but that<br />

motivates me even more to keep on working here and<br />

to try to give people new ideas and a handhold to<br />

change society in a radical and revolutionary way.<br />

Jeroen is an active volunteer at het Fort van<br />

Sjakoo, a non-commercial and collectively run<br />

bookshop with a focus on critical and insurgent<br />

literature.<br />

Published Titles<br />

Every once in a while, Fort van Sjakoo publishes<br />

their own books through profits generated from<br />

the bookshop. In an attempt to illuminate some of<br />

the ways in which the bookshop plays an active<br />

role in supporting the local community, I asked<br />

Jeroen to write about their published titles.<br />

Wat niet mag kan nog steeds<br />

Kraakhandleiding 2015/2016<br />

Author: Anonymous<br />

Year: 2015<br />

This book is a manual for how to prepare a<br />

squatting action in the Netherlands. It tells about<br />

the practical side: searching an empty space, checking<br />

whether it’s really empty, who the owner is,<br />

building plans, how to prepare the squatting action<br />

itself etc. As squatting has been illegal since 2010,<br />

the book tells your legal rights and the possible<br />

risks you run. Furthermore, it tells about security,<br />

barricading the house, good locks, legal support<br />

from squatters’ advice collectives and legal aid<br />

from a lawyer.<br />

Anarchisme breekt door in de kunst<br />

Kunst en anarchisme in Nederland tussen 1880-1930<br />

Author: Andrea Galova<br />

Year: 2012<br />

Andrea (a volunteer at Fort van Sjakoo) wrote her<br />

masters thesis on the interaction between graphical<br />

artists and the anarchist movement in the<br />

period between 1880-1930. She describes the early<br />

years of Dutch anarchism until the start of World<br />

War Two, and the role which graphical artists<br />

played in its propaganda and publishing. Presented<br />

in this thesis are the works of following artists: Chris<br />

Lebeau, Herman J. Schuurman, Luc Kisjes, JJ<br />

Voskuil, Meile Oldeboerrigter, Nico de Haas and<br />

more. She also tries to analyze the visual language<br />

and recurring patterns and symbolism illustrated<br />

with original material from the period.<br />

Met Emmer En Kwast<br />

Veertig Jaar Nederlandse Actieaffiches 1965-2005<br />

Author: Eric Duivenvoorden<br />

Year: 2005<br />

Eric, a former squatter and sociologist, describes<br />

the trends in poster-making in the Dutch radical<br />

social movements from 1965 to 2005. He selected<br />

various posters from the archives of the International<br />

Institute of Social History and categorized them<br />

according to theme. He describes trends in layout,<br />

text-use, trending issues through the passage of<br />

time. The book includes a CD-ROM with high-resolution<br />

scans of 7500 posters.<br />

-Text written by Jeroen<br />

Acknowledgements Thank you to Jeroen (and members of<br />

Het Fort van Sjakoo) for your time and allowing me to share<br />

your unique history and experiences.<br />

Next Issue: An interview with Robin, a former history teacher<br />

who is volunteering at het Fort van Sjakoo.<br />

Book/Action is a research project initiated by Yoshiko Teraoka.<br />

For enquiries, please email yoshi.teraoka@gmail.com

JODENBREESTRAAT 24 1011 NK AMSTERDAM