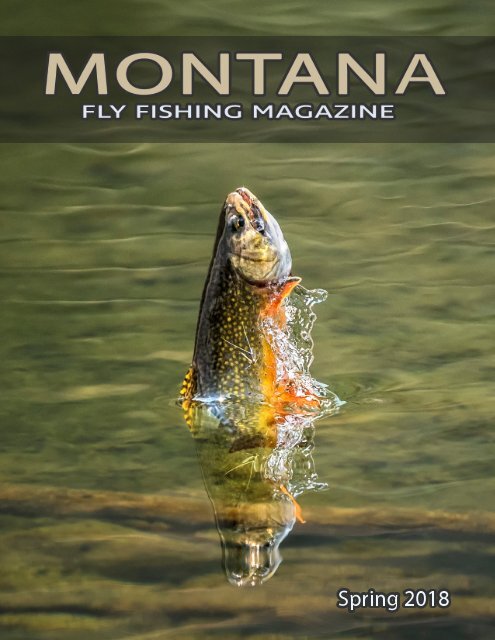

Spring 2018

Montana Fly Fishing Magazine is the FREE digital magazine devoted to fly fishing in the great state of Montana.

Montana Fly Fishing Magazine is the FREE digital magazine devoted to fly fishing in the great state of Montana.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Spring</strong><strong>2018</strong>

Treat Yourself To a<br />

Fly Fishing<br />

Getaway!<br />

VISIT<br />

Located Near Cascade<br />

Just Minutes<br />

From Craig<br />

on The<br />

Mighty<br />

Missouri River!<br />

Book your vacation at<br />

vrbo.com/434225<br />

George & Cathy<br />

Amundson<br />

(406)870-0685<br />

Find us: facebook.com/JumpingRainbowLodge

Welcome back!<br />

We have another FREE online-issue lined up for you. This one is loaded with amazing<br />

imagery supplied by some incredibly talented local photographers and artists. We<br />

also have some solid written work too on Fall brown trout tactics, fly tying, and even<br />

a piece outside our region as we sometimes like to add, this time Alaska. So, be sure<br />

and check them all out.<br />

If you enjoyed reading the investigative article in our <strong>Spring</strong> 2017 issue, about Big<br />

Sky Resort and the developers’ plans to discharge effluent into the Gallatin (an idea<br />

which has been recently nixed by TU, American Rivers, and GYC) get ready; as we<br />

have another one for you. This time the subject is on the Yellowstone River fishkills,<br />

which began in 2016, causing FWP to close a 183-mile stretch of the river that<br />

summer, then a secondary, unexplained, kill in summer of 2017. While some have<br />

written this off as a naturally occurring event, the kills remain scientifically unsolved.<br />

New information gathered by Montana Fly Fishing Magazine reveals interesting and<br />

never before released information about this event. We also interview a 30-year<br />

expert on bryozoans and PKD* in trout, and what is revealed will be surprising to<br />

many.<br />

To top it off, we’re beginning an online campaign to independently bring in this<br />

expert and his team to conduct extensive research on the Yellowstone, in July of<br />

<strong>2018</strong>. You too can be a part of this unprecedented endeavor by donating toward<br />

these efforts.<br />

We’ve always remained a FREE online-magazine and never actively requested<br />

donations from our subscribers. Today, however, we do request that you go to the<br />

Go Fund Me account, provided at the article’s conclusion, and give as generously as<br />

you can toward this unique PKD research project. All proceeds collected online go to<br />

the research team and the proposed project.<br />

It’s important to our western rivers that we gather more scientific data, by actual<br />

experts in the field, on what potentially caused the largest fish-kill in Montana’s<br />

history.<br />

Thank you,<br />

Greg Lewis<br />

Publisher / Montana Fly Fishing Magazine<br />

*PKD refers to Prolific Kidney Disease

Montana Fly Fishing Magazine<br />

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

Volume 6 Issue 1<br />

www.MontanaFlyFishingMagazine.com<br />

Senior Editor:Greg Lewis<br />

Contributors:<br />

Craig Campbell<br />

Pat Clayton<br />

Zack Clothier<br />

Ed Coyle<br />

Terry Dunford<br />

Stephen C. Hinch<br />

George Kalantzes<br />

Greg Lewis<br />

Jodi Monahan<br />

Jason Savage<br />

Stacey Schad Randall<br />

Charlie Smith<br />

Ehren Wells<br />

General Inquiries and Submissions:<br />

mtflyfishmagz796@yahoo.com<br />

Cover Image: Zach Clothier

MONTANA FLYFISHING

MONTANA FLYFISHING

MONTANA FLYFISHING<br />

Pho

tos By Ed Coyle Photography<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Harrison Lake, Self Portrait. Image By George Kalantzes<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

MONTANA FLYFISHING

St Marys Lake. Image By George Kalantzes<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

GEORGE KALANTZ<br />

SPECIALIZING IN LANDSCAPE<br />

TROUTTAILS@Q.COM<br />

WWW.GKALANTZESPHOTO

ES PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

AND SCENIC PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

PH: 435-703-4569<br />

GRAPHY.ZENFOLIO.COM

8 Tips for<br />

Fall

Browns<br />

Written by Ehren Wells<br />

Photo: Charlie Smith

When to go.<br />

The best time to begin fishing for fall browns can vary slightly from year to<br />

year but is generally found from mid-September through October, after the<br />

crowds have pretty much cleared out for the year and the fall colors have<br />

reached their prime. If you’re planning a trip to Yellowstone country, be aware<br />

that fall weather here is on a different timeline from that of much of the state,<br />

bringing early ice and road closures, so it is advisable to plan to fish earlier<br />

rather than later in the fall.

Know your boundaries.<br />

Before planning your fall brown trout excursion, it is a good idea to familiarize<br />

yourself with the park boundaries. You will need to buy a separate license for<br />

the either side of the boundary you wish to fish – a Montana license won’t cover<br />

you in the Park and vice-versa – and each side of the boundary has its own<br />

regulations covering harvest, possession, and gear requirements.

Playing the weather game.<br />

Slow down, stay warm. Fall air temperatures in and around the park generally<br />

run 10-20F cooler than Bozeman and Ennis, with nighttime temps often<br />

dipping into the teens and twenties. Weather cycles and road conditions<br />

also can be dramatically different. You could leave bluebird skies in town and<br />

drive into a blizzard near your destination.<br />

As the saying goes, hope for the best but prepare for the worst. It’s easier to<br />

remove a layer than it is to put on a layer you forgot to bring with you. Even if<br />

I don’t plan on wearing them, I often carry an extra pair or two of my warmest<br />

socks,a warm hat, and long underwear, and a heavy winter jacket to go under<br />

my waders if I get too cold. It is also not a bad idea to keep a spare change of<br />

warm dry clothes in the vehicle in the event of an unexpected plunge.<br />

Perhaps everyone’s worst pet peeve this time of year is ice in the rod guides.<br />

Unfortunately, there’s little that can be done to curtail this time-sucking<br />

line-grabbing menace. Solutions range from applying a coat of Vaseline or<br />

Pam cooking spray to your line and guides to just flat staying home. My solution<br />

is to hit the water anyway and take time to dunk the affected guides in<br />

the water and swish the rod back and forth a few times to melt the ice, and<br />

perhaps crunching it away with my fingertips if that seems to be taking too<br />

long. The same technique can be used to free an ice-bound reel, although<br />

submerging a reel in sub-freezing conditions can put the brakes on the spool<br />

in a hurry, locking your setup into an impromptu Tenkara mode… not exactly<br />

the ideal situation for tackling a beefy brown on 50 feet of line.

Matching the rod (not just the fly) to the hatch.<br />

For most applications, a nine-foot five- or six-weight single-hand rod will work<br />

just fine. However, since the topic here is targeting larger than average prespawn<br />

browns, there are some things to consider when gearing up for a<br />

specific tactic.<br />

If you plan to focus on nymphing, you might look for a 10-foot with medium action<br />

and good sensitivity. An extra foot of rod length can help cover more water<br />

with each cast, and lift more line off the water to eliminate drag.<br />

If you plan to chuck sizeable streamers at pocket water and behind structure<br />

“bank robber” style with your single-hander, consider going up a weight class<br />

or two to a 7, 8, or even 9-weight. A bit more backbone will handle the larger<br />

flies and lessen the time it takes to haul that bruiser to the net.

If making long casts is your game, consider fishing with a two-hander, like a<br />

switch rod or a short (11’-13’) Spey rod. Spey casting strokes allow for greater<br />

distance when bank vegetation limits your backcast. A minimum of a<br />

6-weight two-hander is recommended for throwing streamers, consider a<br />

9- or 10-weight for handling heavy articulated patterns. Two-handed rods<br />

can also be rigged for nymphing. Long-belly “Speydicator” lines allow for<br />

extremely long drag-free drifts. Being on the longer side as opposed to most<br />

single-handers, and two-handed rod allows you to fish and retrieve a longer<br />

nymphing leader without the necessity of beaching your catch in order to land<br />

it.

Feeding those hungry browns.<br />

Fall browns are notorious for being hungry and aggressive, meaning they can<br />

be targeted with dry flies, nymphs, and streamers.<br />

Dry fly: Greater Yellowstone in the fall can provide a world-class level of dryfly<br />

action. Often times, as temperatures rise in the afternoons and evenings,<br />

midges and mayflies can hatch to the point that the fish will feed on little else.<br />

It is not uncommon to find a pod of a dozen or more fish exceeding 18” chowing<br />

down on these insects. Bringing one of these fish to hand can be highly<br />

challenging but also highly rewarding. It often takes time to discern exactly<br />

what the fish are keyed into, though varying midges, Parachute Adams, BWOs,<br />

and Callibaetis are good starter flies. You might identify four or more insects<br />

present in the feeding lane, but only one imitation will work, forcing you to try<br />

multiple patterns/combinations before dialing it in. Conditions may also force<br />

you to put effort into getting the presentation and placement right. A foot one<br />

side or the other of a lane might be asking a trout to go too far out of its way.<br />

The slightest ripple or v-shape from drag can ruin your drift.<br />

Nymphs / Subsurface: If you’re looking to land a number of fish, with the idea<br />

being that the more you land the better your odds that a few will be larger<br />

than average, then nymphing is likely your best bet. Golden stones, like Pat’s<br />

Rubberlegs, Copper Johns, Pheasant tail nymphs, Prince nymphs, and Hare’s<br />

ear nymphs, and San Juan worms should be in every angler’s fly box.<br />

Streamers: For many, fall brown trout fishing is synonymous with streamer<br />

fishing, and by and large these are indeed the best patterns for singling out<br />

large and aggressive pre-spawn brown trout. If you’re fishing a lightweight<br />

single-hand rod, single-hook streamers (Baitfish Emulator, Gonga, Sasquatch,<br />

Kreelex) are most effective. Heavier setups are needed for articulated flies<br />

(Circus Peanut, Sex Dungeon, Drunk ‘N Disorderly, etc). Streamers come in an<br />

array of colors, and if you go to buy these flies at the fly shop, you can empty<br />

your wallet in a hurry. To narrow down your selection, I’ve found it best to stick<br />

with natural colors. It may be somewhat ironic to point out that the best colors<br />

for catching big brown trout are often those you find in a baby brown trout<br />

(yellow, orange, brown, etc). I don’t know if there are scientific papers on this,<br />

but my feeling is that patterns with eyes get better results.<br />

A sink tip (T-6 to T-11) or some split shot placed a few inches away from the fly<br />

can help drop a streamer into the strike zone quickly – an essential component<br />

to success when conducting a vigorous “seek and destroy” mission down the<br />

far bank.

Be bear aware.<br />

Whether you’re headed out for a week or an hour, it’s important to remember<br />

that this is bear country. The bears don’t care if you are “only fishing,” and<br />

Fall is primetime for grizzly and black bear activity. Just a few weeks ago, a<br />

resident outside of West Yellowstone shot and killed a grizzly that came onto<br />

his porch looking to make lunch of the freshly killed elk he had hanging in the<br />

garage. The same rules apply to fishing as with hiking and backpacking: travel<br />

with partners, make noise (particularly where visibility is low), keep your food<br />

in storage when you’re not cooking or eating it, carry bear spray and know<br />

how to use it. These precautions can certainly help minimize your encounters<br />

with a bear, and they can help you keep distances between you and other species<br />

that can do you harm if too close. These include bison, elk, moose, and<br />

even river otters.

Angling Pressure<br />

For those who live to fish in southwest Montana during the fall one of<br />

the allures, beyond the hope of landing a big feisty brown, is taking time<br />

to enjoy the scenery and be part of the landscape. These days it can be<br />

tough to find solitude, so don’t be surprised if you arrive at your dream<br />

hole to find another angler fishing through it. On the flip-side, you might<br />

be blissfully lost in your fishing, content that you’ve got the hole all to<br />

yourself, when another party shows up and tries to muscle in.<br />

When deciding what to do in these situations, consider what is needed to<br />

preserve the quality of the experience for all involved. Even if it appears<br />

obvious that you both have plenty of room to fish, it is considered courteous<br />

to announce your intention or ask your fellow sportsman if he’s alright<br />

with your stepping in. Likewise, if you’ve already put good time in, it’s<br />

considered good form to allow a little room. Low-holing, or stepping in below<br />

and angler within reach of where he’s fishing, or where he soon might<br />

be fishing, is almost never considered acceptable stream-side etiquette.<br />

It’s better to begin at the top of a hole or run and then fish down, the assumption<br />

being that downstream anglers have already fished through.<br />

If you find it difficult to fish a stretch effectively without someone interfering<br />

with your cast or presentation (or your interfering with someone<br />

else’s), consider stepping back and allowing the other angler(s) a turn. If<br />

push comes to shove, move to another stretch up or down stream; or go<br />

back to your vehicle and try putting some miles between you.

Where to find them<br />

Big browns can be found almost anywhere in the fall, but some places are<br />

more likely than others. Riffles likely aren’t your best bet, though it’s never a<br />

bad idea to hit a bucket if it looks just right. Give these places a knock on the<br />

door and move on if nobody’s home. The same can be said of structure. Any<br />

structure that lies in slow water or slows the water down, like a protruding log,<br />

a boulder, or an undercut bank, can hold a brown looking to ambush its prey.

These spots can and do often hold big browns, but don’t spend too much time<br />

in any one spot. Instead, it’s best to focus on deeper, slow-moving water,either<br />

in the form of deep hole, say at the end of a bend, or a long, steady run with a<br />

distinct separation in water speeds at the seam.

IdahoA

PATAGONIA • SIMMS<br />

KORKERS • WINSTON<br />

TENKARA • TFO<br />

REDDINGTON • HATCH<br />

ABEL • ECHO • SAGE<br />

WATERWORKS/LAMSON<br />

Idaho’s Premier<br />

Flyfishing Shop<br />

FULL-SERVICE SHOP<br />

GUIDING • TRAVEL<br />

HOSTED TRIPS<br />

CLASSES<br />

ngler.com <br />

208-389-9957<br />

1682 S. Vista Ave • Boise

Yellowstone<br />

Montana Fly Fishing Magazine interview<br />

on the subject of what caused the u<br />

Written by Greg Lewis, Publisher<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

River Killer!<br />

s a 30-Year Expert in Bryozoans and PKD,<br />

nsolved fish-kill from 2016-2017<br />

By most guide and outfitter<br />

accounts the Yellowstone<br />

River has recovered from<br />

the year-long event from<br />

2016 to 2017, and in some<br />

cases as far as fishing goes<br />

anglers are catching more<br />

trout per-mile than whitefish<br />

in the past. So why revisit<br />

this unfortunate episode in<br />

our state’s past, some might<br />

be asking?<br />

…Because the event still<br />

remains scientifically<br />

unsolved.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

What we know:<br />

In the summer of 2016 the Yellowstone River began experiencing the largest<br />

recorded fish-kill in Montana state history. This unprecedented event caused the Fish<br />

Wildlife and Parks Department to close the river for a 183-mile stretch, as well as all<br />

its’ tributaries for over a two-month period during peak fishing season. This extensive<br />

closure resulted in a loss of angling and area tourism business totaling over $500,000.<br />

What we didn’t realize at the time:<br />

Contrary to multiple articles in the local and national press through misinformation<br />

provided by Region- 3 FWP, anglers across the globe were led to believe that only<br />

native whitefish were killed by the tens-of-thousands in the original event during the<br />

river-closure in summer of 2016. This is untrue. Thousands of rainbow, cutthroat,<br />

and brown trout, were also decimated during this episode, as the unexplained kill-off<br />

carried on throughout the winter and lasted well into the summer of 2017.<br />

This new information was revealed within internal reports and research-work<br />

conducted by FWP over the past 16 months, obtained by Montana Fly Fishing<br />

Magazine, through special-request in January <strong>2018</strong>.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Timing - August 2016:<br />

At the time of the initial fish-kill in August of 2016, I was living in Big<br />

Sky fulltime. There we had recently experienced what a river looks<br />

like only months earlier, in this case the Gallatin, when on April 2015,<br />

30-million-gallons of muddy wastewater spilled out of an effluent pond<br />

discoloring the river for over 50 miles. Information had materialized<br />

soon afterward amongst those in the conservation community about<br />

the potential for direct-discharge in the near future; so, my focus as a<br />

journalist was on effluent, capacity-issues, and treatment.<br />

Given that mindset while I was reading the news of the Yellowstone<br />

river-closure, I began to wonder if the fish-kill might be related to the<br />

upcoming 100 th Anniversary of Yellowstone National Park and the<br />

anticipated 1-million visitors?<br />

I asked myself a basic mathematical question, how could the small<br />

rural-facility designed for 1,800 local Gardiner residents be handling the<br />

volumes of raw wastewater being produced, by what had already been<br />

estimated to be an arriving 900K in tourists annually, over the previous<br />

year?<br />

I did some preliminary research online and realized the Gardiner plant<br />

was renovated in 2012, advertised as state of the art at the time, yet<br />

and it was designed for 600,000 annual visitors. The plant has not been<br />

expanded since that time, to adjust for the significant increase in tourism<br />

(+300K-400K).<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

I then began looking into bryozoans and Prolific Kidney Disease in fish<br />

species (PKD) online. After a couple days of research, I came up with a<br />

name of an expert in the field of “bryozoans and PKD in trout” - the very<br />

culprit FWP was now blaming on the massive fish-kill occurring. Since<br />

there appeared to be very few scientists dedicated to this field of research,<br />

I emailed Dr. Timothy Wood and after a brief introduction, I asked him this<br />

question:<br />

Q) Is it possible, in your professional opinion, the wastewater treatment<br />

plant in Gardiner inadvertently flushed some type of bryozoans into the<br />

river over the few weeks leading up to the initial fish-kill in August 2016;<br />

inadvertently causing this event?<br />

Twenty-four hours later, this was his reply appearing in my in-box:<br />

A) The short answer is: Definitely yes, the<br />

discharge of nutrient-rich water at Gardiner<br />

could be an important factor in the spread<br />

of PKD downstream.Some bryozoans<br />

do thrive in wastewater plants, and it is<br />

conceivable that the plant in Gardiner is<br />

discharging statoblasts or live bryozoan<br />

fragments.<br />

Whether or not this is really happening, and<br />

if so whether those bryozoans are infected<br />

with PKD are things we could easily check.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

I then followed-up with this question:<br />

Q) FWP originally stated the bryozoan and PKD parasite was “an invasive<br />

species, likely introduced by an angler or boater” and that “the fish in the<br />

Yellowstone River were naive to it”. Does this sound accurate?<br />

A) Bryozoans and their associated PKD parasites have probably been in<br />

the Yellowstone River since the last glaciation.<br />

In general, the infection rates are thought to be low and hardly<br />

noticeable. If the latest fish kill was really caused by PKD the most<br />

likely reasons would include: (1) Increase in the infection rate among<br />

bryozoans, (2) increase in the bryozoan population, (3) a lowered<br />

resistance to infection among fish, and (4) a change in the virulence of<br />

the parasite.<br />

Dr. Timothy Wood has published over 60 scientific papers, books, and book chapters on<br />

freshwater bryozoans;<br />

* Named 26 species of bryozoans;<br />

* Conducted full bryozoan surveys in Ohio, Illinois, Britain, Ireland, Panama and Thailand;<br />

* Published the first molecular genetic phylogeny of freshwater bryozoans;<br />

* Currently serving as elected President of the International Bryozoology Association.<br />

An FWP Introduction Gone Wrong<br />

This information (above) shared by Dr. Tim Wood, was then immediately<br />

relayed to FWP officials at the public meeting in Livingston on August 24<br />

2016. The meeting was designed for FWP to explain the river-closure and<br />

was attended by over 300 concerned locals, a senator, and news media.<br />

About 20 minutes before it began I spoke to Sam Shepard, who was at the<br />

time Region 3 Supervisor, as well as Dr. Eileen Ryce. I read the information<br />

that the expert had said “the bryozoan and parasite have been in our rivers<br />

for hundreds of years and are commonly transported by waterfowl”, thus<br />

impossible to control. They both openly dismissed my input, then went on<br />

stage to further spread a false narrative riddled with multiple inaccurate<br />

statements, as to what was occurring on the river.<br />

trout pose<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

All attempted connections afterward between actual experts on bryozoans<br />

and Region 3 FWP, were dismissed in 2016.<br />

After reading countless articles filled with false information between Region<br />

3 Fisheries and the press, as well as a second fish-kill occurring in the<br />

summer of 2017, (when recorded-flows were higher and water temps much<br />

colder), I decided to conduct this in-depth interview.<br />

– What is a Bryozoan?<br />

Bryozoans (literally<br />

“moss animals”) are small, invertebrate animals that<br />

grow as branching colonies attached to submerged surfaces.<br />

Often they resemble brown moss or plant roots and so they<br />

attract little attention. Using tufts of ciliated tentacles<br />

they feed on microscopic particles in the water. In turn,<br />

they provide food and shelter for insect larvae that help<br />

support fish populations. Bryozoans occur in lakes and<br />

rivers worldwide as a normal part of any healthy freshwater<br />

community.<br />

New Information<br />

Q) Would bryozoans be considered an “invasive species” such as zebra<br />

mussels?<br />

A) No, not at all. The bryozoans harboring PKD are well established<br />

across five continents. They occur throughout North America, especially<br />

in cold, flowing waters like the Yellowstone River. By contrast, zebra<br />

mussels invaded North America from Europe about 30 years ago and we<br />

are now seeing them move across southern Asia - a true invasive species.<br />

Q) How is the bryozoan most commonly spread from river to river and<br />

commercial bodies of water?<br />

A) Most freshwater bryozoans produce dormant capsules about the size<br />

of a period in newsprint. Called statoblasts, these can survive freezing,<br />

drying, and other harsh conditions. We know that statoblasts are<br />

easily transported by waterfowl - on the feet, feathers, and even in the<br />

digestive tract. However, I have found bryozoans in glacial lakes at high<br />

elevations where waterfowl seldom go, and I have no idea how they got<br />

there.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Q) Besides your 30+ years as a professor at Wright University in Ohio, you<br />

also own and operate a commercial company called: Bryo Technologies,<br />

which routinely treats certain commercial facilities of bryozoan outbreaks.<br />

(www.bryotechnologies.com). What types of problems can bryozoans cause<br />

inside these facilities and what does your company do to stop the spread?<br />

A) The problems we fix begin when water from a lake or river is drawn<br />

through a pipeline. Very soon things are growing on the inner pipeline<br />

walls. Among these are zebra mussels, which most people know, but<br />

there are also bryozoans, hydroids, peritrichs, sponges, and other<br />

unfamiliar aquatic pests. They can completely block a pipeline, or if<br />

they break loose they can clog equipment.<br />

This is what we deal with, and it is a very common problem. Every<br />

situation is unique, but over the years we have developed a variety of<br />

successful methods to handle them.<br />

Q) How many years have you been studying bryozoans and their association<br />

with Prolific kidney disease in trout species?<br />

A) As a graduate student in Colorado in 1968, I discovered a way to<br />

grow bryozoans in the laboratory. One of the species I worked with was<br />

Fredericella, which is now known to be the primary carrier of PKD. In<br />

those days I knew nothing of PKD but I did notice tiny, sac-like things<br />

moving around inside the bryozoans, very likely the PKD parasite itself.<br />

Years later I collaborated with Dr. Beth Okamura to study myxozoan<br />

parasites in bryozoans, which led directly to discovering the link<br />

between these parasites and PKD in salmonid fish.<br />

Q) What is the relationship between PKD and bryozoans?<br />

A) PKD is essentially a bryozoan disease. Bryozoans with PKD can<br />

infect other bryozoans, they can infect the next generation of bryozoans,<br />

and they can also (accidentally) infect salmonid fish.<br />

Fish with PKD cannot pass the disease to other fish, they can only reinfect<br />

bryozoans. So, without infected bryozoans there would be no<br />

PKD in fish.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

MONTANA FLYFISHING

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Q) In spring of 2017, FWP reported they found an entire larger age-class<br />

of trout missing from the Yellowstone river in roughly the same general<br />

location as 2016 year’s fish kill*. While they initially reported that the public<br />

shouldn’t make the connection to last year’s event, given ice scourging and<br />

possibly it being a cyclical event was to blame, now that we experienced<br />

another fish-kill this past year, isn’t it plausible that we’re actually<br />

experiencing a PKD event still unfolding?<br />

A) It does seem unlikely that there would be a single isolated PKD<br />

event without the effects rippling into the following years. But I would<br />

emphasize that we know little about how PKD operates in the natural<br />

world. Most of the research so far has been clinical, not ecological.<br />

Regrettably, there are no PKD data from the Yellowstone River in years<br />

prior to the recent fish kills.<br />

*Source: Link<br />

Records provided by FWP in <strong>2018</strong> show “a population decline, of as<br />

many as 50% in all trout species”: Brown, rainbow, and cutthroat occurred<br />

between 2016-2017 on the most impacted stretches due to PKD. This<br />

information was verified in more detail within FWP’s internal records and<br />

research work, which was obtained by Montana Fly Fishing Magazine in<br />

January <strong>2018</strong>.<br />

……………….<br />

Q) In your scientific research could a substantial increase in arsenic, which<br />

was being introduced to the wastewater facility in Gardiner, have any impact<br />

on the bryozoans present?<br />

A) Possibly, but the fish would be affected even more.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Arsenic –<br />

It was revealed in an article published in the Bozeman Daily Chronicle on Oct. 20, 2017 that<br />

“high levels of arsenic were found in the district’s sewage treatment facilities”, originating from<br />

a leaking pipeline in YNP. This has now resulted in a $2-million-dollar lawsuit. According to the<br />

complaint an engineer told the district in February 2015 that high levels of the odorless chemical<br />

were entering the treatment facility. The engineer also said that 95 percent of the arsenic was<br />

coming from Yellowstone, and testing showed the park’s sewage had levels nearly 40 times that<br />

of Gardiner sewage.<br />

The Montana Department of Environmental Quality had directed the district to empty the ponds,<br />

but the engineer recommended they wait to do so until the park fixed its arsenic problems,<br />

according to the complaint. The Gardiner treatment facility legally and routinely discharges its<br />

treated effluent into the Yellowstone River. Source: Link<br />

Second Recorded Fish Kill – August 2017<br />

Q) Is it possible that the theory which FWP reported as recently as August<br />

2017, “that the bryozoan colony, or host, was swept below last years’ killsite<br />

during ice-out”, and now this is why the 2017 fish-kill occurred 20 miles<br />

downstream?<br />

A) No, this does not strike me as very plausible. Most freshwater<br />

bryozoans overwinter in the form of dormant statoblasts attached firmly<br />

to rocks. It is unlikely that these would be significantly affected by ice-out.<br />

Q) In your experiences treating wastewater facilities and nuclear cooling ponds<br />

for bryozoan outbreaks how does the bryozoan grow to some problematic<br />

proportions and what does your team do to stop it from recurring?<br />

A) Many bryozoans grow best with continuously flowing water and<br />

plentiful food. To control these populations, we use a variety of chemical<br />

and nonchemical tools, all depending on the species, water chemistry, and<br />

characteristics of the site. There is no single solution that works in every<br />

case.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Q) At the heart of the 2016 fish-kill and where biologists also located dead whitefish<br />

again in 2017, a vital tributary, or artery known as Mill Creek, has long since been cutoff<br />

from reaching the river due to ranchers’ diverting 100% of its spring and summer<br />

flow.<br />

That much lower volume, (if any) which does eventually enter the river, after usage for<br />

commercial scale agriculture is then from irrigation ditches or leaching along the edges<br />

of fields; with fertilizers mixed within the water. Could this be a possible factor in the<br />

spread or bloom of bryozoan colonies, and a potential cause of PKD outbreaks in the<br />

hardest-hit areas?<br />

A) Possibly. We do know that elevated nutrient levels in the water promote<br />

strong growth in bryozoans. Whether this also promotes higher infection rates by<br />

PKD parasites is not known.<br />

…………………………………….<br />

Q) Could a wastewater plant performing a by-pass, either authorized or unauthorized,<br />

and sending into the river system untreated sewage be the cause of the bryozoan/PKD<br />

outbreak?<br />

A) Yes. It has been shown that the nutrients from wastewater have a positive<br />

effect on the growth of bryozoans, including the species that carries PKD.<br />

Q) There were reports by FWP in May 2017, of “septic shock as the cause of death<br />

in whitefish in the hardest hit areas of the 2016 fish-kill”. Does this sound correct?<br />

Have you or colleagues ever experienced or witnessed anything on this scale before in<br />

hatcheries or in nature?<br />

A) I am not aware of any instance where a massive release of PKD spores<br />

resulted in septic shock in fish. If this has been reported by FWP it would be<br />

reasonable to inquire about any evidence.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Q) Why is FWP calling Prolific Kidney Disease now PKX?<br />

A) PKD is proliferative kidney disease; PKX is an old term for the parasite<br />

causing PKD. For a long time, it was clear that another species was involved<br />

in the life cycle, but no one could discover what it was. The “X” represented<br />

the unknown species. Now that bryozoans are known to be the final hosts the<br />

expression “PKX” has fallen out of use.<br />

Q) Can anglers do anything to help stop the spread of bryozoans from one river to<br />

another?<br />

A) It is always a good precaution to hose off boots and other equipment<br />

before entering a new fishing site. Live bryozoan fragments or statoblasts<br />

can adhere to fishing gear, especially in standing water. The statoblasts remain<br />

viable even after being dried or frozen for months.<br />

Q) FWP stated in early media reports and also at the meeting held in Livingston<br />

after the Yellowstone River-closure, that they “had only located both the bryozoan<br />

and PKD parasite in two isolated locations in the past 20 years, Cherry Creek and<br />

an irrigation ditch (neither related to a fish-kill)”; yet in your paper on the subject:<br />

Bryozoans as hosts for Tetracapsula bryosalmonae, the PKX organism it was<br />

recorded as present in Ennis Lake and the Lower Madison in 2000.<br />

How did you come to find both the same bryozoan and PKD parasite in this<br />

region and for whom were you doing research at the time (or from where was that<br />

information gathered)?<br />

A) From various sources we compiled a list of sites where PKD had been<br />

reported. The goal of this study was to find out what bryozoan species occur<br />

in the same vicinities. The species we found were well known across the<br />

northern states. This work was funded by the Natural Environment Research<br />

Center in the UK.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Q) The question most asked after these back-to-back fish kills is why the Yellowstone<br />

river is seeing reactions when both the bryozoan and parasite are in all of our rivers? If<br />

it were merely temperature and flow rate which is triggering it, certainly the Jefferson,<br />

Lower Madison, or Big Hole, should have experienced mass fish-kills, since both<br />

rivers’ flows are typically lower and warmer (and Hoot Owl restrictions* go into effect<br />

on) well before the Yellowstone’s levels drop.<br />

So why the Yellowstone?<br />

A) Bryozoans are a normal part of any healthy river ecosystem, and they<br />

probably occur in every river system in Montana. However, we do not know<br />

where the PKD parasite occurs or how much of any bryozoan population is likely<br />

to be infected.<br />

*Hoot Owl restrictions are when FWP halts fishing after 2PM to alleviate pressure/stress on trout during high watertemps.<br />

Q) Also, why is a certain section seeing a fish-kill if temperatures and low-flows are a<br />

cause? Others have questioned why wouldn’t the degree of fish-kill be more extreme<br />

much further downriver where water is even lower and thus much warmer?<br />

A) These are good questions that need to be asked. At this time, I have no answers<br />

for you.<br />

Q) Why do you suppose the parasite is targeting whitefish primarily, versus rainbow or<br />

brown trout? Or do you think it is and we’re just not seeing as many of the latter*?<br />

A) Scientists now believe there are many different strains of the PKD parasite,<br />

and some of these may be more lethal to whitefish than to other species. At this<br />

point we are still learning to distinguish one strain from another.<br />

*Information was later revealed within internal FWP reports, to indicate thousands of trout also perished<br />

between the summers of 2016-2017.<br />

Q) Approximately how many times have you corresponded with Montana FWP and<br />

state officials since 2016-2017 fish kills? Have they been asking related questions?A)<br />

We initially made half a dozen contacts with various people. There seemed to be<br />

very little interest, and no one has responded with questions of their own.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Q) In your initial written proposal to FWP in September 2016 you laid out a plan that<br />

you and your team would conduct if the state brought you in to help research the fishkill.<br />

It appears they simply read your outline and followed your proposed methods<br />

themselves. Has anything like this occurred before?<br />

A) Our proposal contained no privileged information. FWP was free to use it<br />

any way they wished. However, following through with those ideas would have<br />

required specific experience and knowledge that FWP seems to lack. For that<br />

reason, they may have given the proposal a low priority. We found a similar nonresponse<br />

from the State of Idaho, where there have been numerous unexplained<br />

fish kills on the Snake River.<br />

Q) Do you think it was perhaps because of budgeting reasons or cost concerns, why<br />

FWP decided not to bring your team in?<br />

A) Cost was never discussed as we’d not yet determined the amount of time<br />

required to investigate the outbreak and its potential causes. I think a more likely<br />

reason is that FWP preferred to focus on the fish rather than the less familiar<br />

bryozoans.<br />

…………………<br />

Proposal for Research - <strong>2018</strong><br />

Q) Would your scientific findings after a two-week research project on the Yellowstone,<br />

then be of benefit to other scientists and students studying PKD outbreaks, once its<br />

completed?<br />

A) Absolutely. Most studies of PKD have been done in laboratories. This would be<br />

one of the first actually performed on site.<br />

Here is what we want to know: What is the population size of bryozoans in the<br />

study area and how are they distributed? What is the infection rate? Can we<br />

identify PKD “hotspots?”<br />

If so, do they suggest possible factors triggering the PKD outbreaks? Can we<br />

identify steps to be taken that would decrease the likelihood of another severe<br />

outbreak?<br />

There may be additional information of interest mainly to researchers: is there<br />

more than one bryozoan species harboring PKD parasites? Is this the same PKD<br />

strain that afflicts trout farms in Europe? Etc.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Q) Could the two events, or back-to-back fish kills on the Yellowstone during August<br />

2016/2017, be something that is naturally recurring and possibly something to some<br />

degree we might experience annually from now on?<br />

A) I certainly hope not. But I think the people supporting this investigation are<br />

taking the right approach. You can speculate all day about PKD outbreaks and<br />

what the future holds for the Yellowstone River, but without reliable data it is just<br />

talk. I look forward to investigating the PKD outbreak area in <strong>2018</strong>. If all goes well<br />

we will be able to provide some real answers.<br />

……………………….<br />

If you’d like to help us come closer to discovering what truly<br />

caused the fish-kills on the Yellowstone River during 2016-<br />

2017, and thus further help prevent similar events in other<br />

western rivers, we are collecting donations toward independent<br />

research.<br />

The costs for bringing Dr. Wood and his team of experts in<br />

to conduct a two-week Bryozoan Mapping Project, in July of<br />

<strong>2018</strong>, are significant - so we’re also searching out major donors<br />

in the fly fishing industry, as well as foundations.<br />

Please log into our Go Fund Me Campaign here:<br />

https://www.gofundme.com/why-the-yellowstone<br />

Here is the link to the <strong>2018</strong> Research Proposal and the dedicated website for more<br />

information: http://www.yellowstoneriverfishkill.com<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Q&A with Craig Campbell,<br />

Builder of Gravitas Boats<br />

Interview by Greg Lewis<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Q) How (and what age) did you get started in woodworking?<br />

I grew up in a house with a wood shop. My father has been a<br />

woodworker longer than I’ve been alive so I was always around tools<br />

and equipment, stacks of wood, and the smell of stain and lacquer. It<br />

was in my early teens when I truly started woodworking and since that<br />

time I’ve built everything from a rubber band pistol to a hand shaped<br />

Sam Maloof rocking chair.<br />

Q) How about fly fishing, when did that bug kick in?<br />

From Canada originally, I moved to Montana in 2001 and with a<br />

degree in Biology and Chemistry worked as a wildlife technician. From<br />

the moment the ice melted I was fishing the streams and rivers and it<br />

wasn’t long before I began fly fishing. I’ve never regretted the decision.<br />

Fly fishing from a wooden drift boat is the only activity where I am<br />

completely relaxed and rejuvenated at the end of the day.<br />

Q) How did you get into making custom drift boats?<br />

I was searching for a drift boat that met my needs and quickly became<br />

frustrated in the lack of personalized options. Given my woodworking<br />

experience I decided to build my own drift boat and that was the<br />

beginning of a passion. I did a lot of online research, bought some<br />

generic plans, and started my build.<br />

It wasn’t long before I had compiled a list of all the changes that<br />

would make the boat a more appropriate fit for me and, as it turns out,<br />

for others as well. I had a great time completing the build and realized<br />

that this was a career I could fully embrace. There are many challenges<br />

in “getting it right” and I’m constantly thinking of ways to improve<br />

drift boat designs but these are reasons why it’s such a rewarding<br />

vocation.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

MONTANA FLYFISHING

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Q) How do you figure out which custom boat design you offer, is ideal for<br />

which customer?<br />

The first and most important conversation that I have with a<br />

customer centers around what type of water they float and how they<br />

plan to use their boat. Not every drift boat owner is a fly fisherman. A<br />

family may simply want a hard-bottomed boat which will offer both<br />

stability and safety for young kids and their gear. Then of course<br />

there are those who want all the necessary accessories for a great day<br />

of fishing. Wooden drift boats don’t fall out of a manufacturers mold<br />

and consequently they can be designed and built to provide whatever a<br />

customer needs.<br />

Q) How many custom drift boat projects do you take on per year?<br />

My mission statement is built around quality as opposed to quantity.<br />

I’m capable of working on two boats at a time while still paying<br />

attention to the details that set my boats apart. If an interested<br />

customer finds that I am occupied with other orders they are welcome<br />

to join a waiting list. I think the wait will be worth it for them but I<br />

also have boats available for immediate purchase.<br />

Q) What’s the usual turnaround time on a custom wooden drift boat you<br />

build?<br />

It is dependent on the complexity of each boat but the average time<br />

is approximately 4-6 months.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Q) What custom features do you offer?<br />

First and foremost, adjustability. I am working very hard to<br />

make the current designs absolutely user friendly. For example, the<br />

most important feature for a rower is that the boat floats level and<br />

is easy to maneuver. The only way to achieve this is to move weight<br />

throughout the boat accordingly.<br />

The fishing seats in my most recent design have fore and aft<br />

movement set on a track system which is set into the floor. The<br />

rower’s seat has the same fore and aft movement, more than any<br />

other on the market. When the seats are properly positioned based<br />

on weight, the boat will always ride trim. Gone are the days when<br />

the boat’s bow points to the sky or is buried in the water because of<br />

your passenger’s weight and where they are sitting. The seats are<br />

also removeable allowing for a cooler or dog bed.<br />

My boats are designed more closely to the McKenzie style which<br />

means they have the appropriate amount of rocker which equates to<br />

easier maneuverability and less effort to stay stationary at a fishing<br />

hole.<br />

Q) What types of wood are you using when constructing a custom drift<br />

boat?<br />

I use 3/8” marine grade Mahogany plywood for building the<br />

hull sides, dry boxes, decks and hatch covers. 1/2” marine grade<br />

Mahogany plywood is used for constructing the hull bottom and<br />

interior level floors. The gunwales are made of Ash or White Oak,<br />

both of which offer a great deal of strength and are relatively easy<br />

to steam bend. Parts such as the breast hook and anchor mount are<br />

made from Mahogany with Black Walnut accents.<br />

Components that require a great deal of strength, such as the oar<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

lock blocks, the rower’s seat, and adjustable rower’s seat frame are<br />

constructed of White Oak. Unlike other manufacturers who simply<br />

draw the side panels together into a point and then use a stem cap to<br />

protect the bow, I use a solid Ash post which is inset for attaching the<br />

side panels flush to the post. Not only does this provide a structurally<br />

sound bow, it also provides a solid surface for attaching the bow eye.<br />

Ash, White Oak and Mahogany have a very long history in wooden<br />

sailing ships and serve equally well in a drift boat.<br />

Q) What are some of the biggest challenges when building a drift boat from<br />

wood versus fiberglass?<br />

Occasionally a piece of wood will have a flaw below the surface that<br />

reveals itself after the start of the milling process and these are to<br />

be expected on occasion. The solution is to mill a new piece. Wood<br />

has very few challenges that can’t be overcome. It can be cut and<br />

shaped with basic tools, steam bent to provide flowing lines, and easily<br />

repaired. It’s quiet on the water, has a natural insulating factor, and<br />

catches admiring glances and comments from everyone who sees it. It<br />

is a wonderful material to work with and when using the appropriate<br />

species and with a little care, will last a very long time.<br />

Q) Do you test float each craft before delivery?<br />

Every completed boat is loaded onto its size specific trailer and taken<br />

to the river for “trials.” I’m not only getting a feel for the boat in the<br />

water, I also want to confirm that each boat sits well on its trailer and<br />

that the loaded trailer pulls easily at all speeds. Once in the water I’m<br />

listening, looking and feeling how everything is responding to the water<br />

and my oar strokes. Each boat is floated several times to ensure that<br />

the product is perfect. My wife jokes that this is not the time for deep<br />

conversations because I’m usually in a world of my own.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Q) Personal favorite river to float and fly fish in Montana?<br />

The Bitterroot River between Tucker and Florence. The Bitterroot is<br />

my home water and I love every moment I’m floating that stretch. It<br />

doesn’t matter what time of year or whether the fish are biting, it’s one<br />

of those spots that has clear water, spectacular mountain views, and a<br />

lot of structure to hold fish. I do float other rivers but the Bitterroot is<br />

a special place to me.<br />

To learn more about Craig Campbell and Gravitas Drift Boats, visit<br />

http://gravitasdriftboats.com .<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

ROCKY M0l:INTA1N WEST flNE ART<br />

LAND\CAPE I NATURE I WILDLIFE I EVENT<br />

DrstGN I SPACE I LIVING<br />

MIC! IAELCI 11 LCOAT.COM I 406.407.0932<br />

PRINTS· GALLERY WRAPS · METAL PRINTS· CUSTOM ORDERS

Bristol Bay<br />

Sockeye Salmon<br />

A National Treasure<br />

Words and Photos by Patrick Clayton

At the turn of the century,<br />

the industrial revolution ran<br />

like a wildfire up and down<br />

the west coast leaving<br />

ecosystems in tatters and<br />

the once iconic salmon<br />

runs a mere shadow of<br />

their former selves. Dams<br />

were erected, forests were<br />

chopped down, mines<br />

constructed, and irrigation<br />

diversions all sapped<br />

the once vibrant salmon<br />

rearing grounds of what<br />

was needed to sustain their<br />

populations. Canneries<br />

were some of the first<br />

building constructed<br />

along the Columbia<br />

and overharvest was<br />

commonplace. Before we<br />

even knew what existed it<br />

was gone. The keystone<br />

species which supported<br />

all forms of life entered<br />

a precipitous decline<br />

continuing to this day. In<br />

the far north, there was<br />

one place which avoided<br />

this fate, Bristol Bay Alaska.

This vast region was<br />

protected by its shear<br />

remoteness, harsh climate,<br />

and unforgiving wildness.<br />

Like an apparition from<br />

a bygone era, sockeye<br />

salmon still pour out of<br />

the Pacific Ocean by<br />

the millions to these<br />

untouched and pristine<br />

waters. The long arm of<br />

industry long held at bay<br />

now has its eyes squarely<br />

set on developing and<br />

thus destroying this, our<br />

last functioning mega<br />

salmon run. Pebble Mine<br />

is the vanguard industry<br />

which wants to build<br />

massive open pit mines,<br />

dam free flowing rivers,<br />

and drill for oil. During<br />

the Obama presidency,<br />

the mine got a temporary<br />

hold, it has reared its ugly<br />

head once again. The EPA,<br />

under notorious fossil fuel<br />

advocate Scott Pruitt, has<br />

proposed to cancel the<br />

Obama-era determination<br />

that, if finalized, would<br />

have blocked development<br />

at the Pebble gold and<br />

copper prospect in<br />

southwest Alaska.<br />

“Like an<br />

apparition<br />

from a bygone<br />

era, sockeye<br />

salmon still<br />

pour out of the<br />

Pacific Ocean<br />

by the millions<br />

to these<br />

untouched and<br />

pristine waters.<br />

The long arm of<br />

industry.”

No single species defines the Pacific coast<br />

more so than salmon.

No single species defines the<br />

Pacific coast more so than<br />

salmon. While efforts to restore<br />

and preserve these salmon<br />

runs in the lower 48 continue,<br />

in Bristol Bay things exist as<br />

they always have. Salmon;<br />

A thousands year old native<br />

culture rely on them, the tundra<br />

springs to life due to them,<br />

apex predators gorge on their<br />

abundance, and sustainable<br />

economies rely on their return.<br />

The Aleut-Alutiq, Athabascan,<br />

and Yup’ik cultures catch, dry,<br />

smoke, and subsist off this<br />

source of protein as they have<br />

for time and memorial. Their<br />

first language is their own and<br />

they are the most intact native<br />

cultures in North America.<br />

Salmon push to the headwaters<br />

of every available river system<br />

resulting in an irreplaceable<br />

transfer of nutrients from<br />

sea to sky. These still intact<br />

salmon runs support the largest<br />

populations of Grizzly bears on<br />

the planet, caribou herds graze<br />

the salmon fertilized plants,<br />

everything relying on this<br />

food chain even down to the<br />

smallest plants and organisms.

“This place<br />

overwhelms the<br />

senses and enlivens<br />

the spirit; its mere<br />

existence gives us<br />

hope and a place to<br />

dream of.”

Sustainability is more than a<br />

buzzword when it comes to<br />

the commercial fishery. This<br />

massive region supports the<br />

largest sockeye salmon fishery<br />

on earth and is managed in<br />

such a way to go on forever. It<br />

is a billion dollar a year industry<br />

that provides the healthiest of<br />

food to the most discerning of<br />

consumers.<br />

There is not a sportsman<br />

on earth does not dream of<br />

someday wetting a line here,<br />

and this thriving industry in<br />

itself is worth another hundred<br />

million dollars and provides<br />

employment for thousands.<br />

This place overwhelms the<br />

senses and enlivens the spirit;<br />

its mere existence gives us<br />

hope and a place to dream of.<br />

Bristol Bay now faces its most<br />

dire of threats, at its very heart;<br />

mining interests have found<br />

some of the largest deposits of<br />

precious metals on earth and<br />

plan industrial development as<br />

large as any project on earth.<br />

The intensity with which this<br />

ecosystem and landscape<br />

hum is unmistakable. At its<br />

center are Lake Illiamna and<br />

the Nushagak River. Alaska’s<br />

largest lake and its tributaries<br />

are responsible for almost half<br />

the regions sockeye salmon<br />

and represent the largest<br />

salmon run on earth. The<br />

Nushagak is the next largest<br />

producer and one of the top<br />

king salmon rivers on the<br />

planet. The proposed Pebble<br />

Mine is directly above these<br />

drainages and exploratory<br />

mining is occurring throughout<br />

the region. Hard rock mining<br />

of this magnitude spells disaster<br />

for the fish, the culture, and the<br />

ecosystem. In scientific terms<br />

these fish stocks are known as<br />

a strong portfolio. The genetic<br />

diversity guaranteeing their<br />

sustainability and vibrancy.<br />

The potential loss of this core<br />

population threatens not only<br />

the immediate area but the<br />

region as a whole.

Salmon are counted by the<br />

hundreds as they wriggle<br />

over concrete barriers<br />

up and down the Pacific<br />

coast while in Bristol Bay<br />

they are stockpiled by the<br />

millions. So numerous<br />

is this run, if you were to<br />

stack them nose to tail they<br />

would stretch from Bristol<br />

Bay to Australia and back.<br />

The fact that salmon still<br />

exist on many southern<br />

rivers is a testament to<br />

their fierce determination<br />

and evolutionary mastery.<br />

Stragglers still perpetuate<br />

their species amongst the<br />

steepest of odds. Their<br />

efforts know no limit.<br />

A Sockeye salmon known<br />

only as Lonesome Larry<br />

was the only one to return<br />

to a Lake in Idaho after<br />

swimming 900 miles and<br />

passing 8 dams. Redfish<br />

Lake, which in a bygone<br />

era saw tens of thousands<br />

of these oceans going<br />

vagabonds return, had nearly<br />

lost its namesake. This story<br />

has been repeated over and<br />

over from the Puget Sound<br />

to Las Angeles.

The usual culprits who led to the<br />

downfall of our iconic Pacific<br />

Coast species now want a repeat<br />

performance in this last great place.<br />

Bristol Bay is the last treasure in the<br />

chest and it is where the line will be<br />

drawn. Whatever comes down the<br />

pipe, we must be prepared to fight<br />

once again, and this time fight for<br />

permanent protection by whatever<br />

means necessary and never allow<br />

this resource to be destroyed for<br />

the profit of a few.<br />

Words and Photos by Patrick Clayton<br />

www.fisheyeguyphotography.com

About Fly Tying Feathers<br />

~A Beginners Guide~<br />

By Terry Dunford<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

When I first started the art of fly tying, I had many questions<br />

about Fly Tying Feathers. I’ve done extensive research since<br />

then and now aim to provide you with an exhaustive, thorough<br />

guide to Fly Tying Feathers and their uses. This article will<br />

provide you with information about the most used types of<br />

features used in tying flies. I will also include great photos so<br />

you can gain a visual perspective when reading the information<br />

provided to you herein.<br />

Fly tying feathers are usually broken down into two main<br />

categories - Dry Fly Feathers and Wet Fly Feathers. Feathers<br />

are utilized in a variety of ways. For example, feathers can be<br />

used as body material, wings, throats, collars, tails, hackles,<br />

cheeks and sides.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Dry Fly Feathers<br />

The most widely-used feathers for dry fly wings are mallard, wood duck, and<br />

teal flank feathers. Other feathers used include hen, mallard quill and turkey flats.<br />

Certain feathers are selected for their coloration and visual appearance, whereas<br />

others are chosen for their capability to absorb or deter water.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Wet Fly Feathers<br />

Feathers used in tying steelhead, salmon, streamers,<br />

saltwater and other larger flies are often very colorful<br />

and are usually wet flies. Here you will be using the<br />

larger saddle and schlappen feathers from chickens,<br />

flank feathers from many waterfowl species and<br />

some of the more colorful pheasant species. The most<br />

common feathers used for wet flies include marabou,<br />

hen, mallard quill, and ostrich herl.<br />

CDC<br />

CDC is an abbreviation for the fly tying term “cul<br />

de canard.” CDC feathers are exceptionally fluffy<br />

feathers and are also known as “oil gland feathers”<br />

due to the feathers being located close to a duck’s<br />

oil production gland which is the preen gland. This<br />

location enables oils to become absorbed and will<br />

then result in dry flies becoming buoyant and water<br />

resistant (dry). These very useful feathers are available in nearly all colors, including<br />

dark olive, natural brown, medium olive, light dun, yellow olive, white, wood duck,<br />

slate dun, dark brown, light brown, black, salmon, rust, pale and yellow to name a<br />

few. CDC feathers can be used for a very long list of fly patterns, but to name a few<br />

CDC feathers can be used for parachute flies, caddis wings, or looped for emerger<br />

wings. CDC can also be of huge value when used as hackle for both dry and wet fly<br />

patterns.<br />

CDC Oiler Puffs are great for both emergers and dry flies. These tiny feathers lack<br />

observable stems and are frequently called nipple plumes due to the fact that they<br />

are located on the nipple of the preen gland. When tied in as wing posts, these fluffy<br />

feathers entrap lots of air. Oiler Puffs can be tied the usual way, or reverse tied to take<br />

advantage of the naturally integrated bubble created by the base of the feather. This<br />

“CDC Bubble” is usually intended to float the fly in the surface film of moving water.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Marabou, or Blood Quill, is the supple, fluffy, soft feathers from turkeys and chickens and flow marvelously<br />

in the water. Marabou gets its name from the Marabou stork located<br />

in South Africa, which was formerly the singular source of this fluffy<br />

feather. However, in the late 1930’s, it was discovered that turkey<br />

down was incredibly alike, and a new, innovative industry came<br />

into existence. Poultry processing now produces mass quantities of<br />

Marabou.<br />

Marabou is frequently used for tails and wings in flies and jigs. Once<br />

a marabou fly penetrates the water, it immediately becomes lively,<br />

and this dynamic, vivacious act draws curiosity from even the most<br />

laid-back fish. This classic fly tying material is also widely used in nymph patterns and big saltwater streamers.<br />

Marabou is dyed many different colors, and come in numerous different types, such as strung marabou or<br />

blood quills, marabou plumes, wooly bugger marabou, mini marabou, and grizzly marabou.<br />

Of all the diverse feathers used in fly tying, marabou feathers have to be one of the most distinctive and<br />

valuable. The great thing about Marabou is that beginner fly tyer’s can still create realistic replications, which<br />

is great reason why beginning fly tyer’s should use it frequently.<br />

Peacock herl is well-recognized and cherished by fly tyers for its<br />

glistening quality and vibrant color. These feathers are used to imitate<br />

bodies that are energetic and lively when they enter the water. The<br />

finest peacock herl can typically be located near the eye of the feather.<br />

Peacock herl as well as Ostrich plume herl is used as “butts” or at<br />

times as body material on numerous fly patterns. Peacock and Ostrich<br />

herl is also occasionally used as wing, overwing, or underwing<br />

material on numerous streamer fly patterns. Peacock Herl is also<br />

commonly used to form naturally flashy tails, great great looking<br />

nymphs and other various types of bodies.<br />

Pheasant<br />

The most commonly used pheasant feathers are taken from the Ringneck pheasant; however, there are various<br />

fly recipes that call for Amherst or Golden pheasant neck feathers. Ringneck pheasant whole skins can be<br />

a tremendously precious asset to any fly tyer because any tyer should be able to tie hundreds of flies with<br />

just one full skin. Pheasant Tail feathers can, as usual, be tyed to imitate bodies, legs, wingcases, and tails.<br />

Pheasant body feathers can be used to create very appealing.<br />

Most of the pheasant feathers can be used for one thing or<br />

another. There are many species of pheasant, which in the tying<br />

field usually include Ringnecks, Golden, Silver, and Amhearst<br />

just to name a few. The crest (head) feathers from the Golden<br />

and Amhearst pheasant are frequently used as tails on Atlantic<br />

salmon, Steelhead, and other fly patterns. Body feathers of the<br />

Golden Pheasant can be used to tie on wings, body hackle and<br />

tails.<br />

About the Author<br />

Fly Tying enthusiast Terry Dunford has been a very active fly-fisherman and fly tyer for decades and has<br />

worked 10 years for Platte River Fly Shop in Casper, Wyoming and has written several articles on the topics of<br />

fly tying and fly-fishing. For any questions or comments, please feel free to call the author at (435) 862-8151.<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

and be entered to WIN<br />

FR<br />

SUBSCR<br />

Subscribe to Montana<br />

CLICK HER<br />

* Open to all current and new subscribers.

Fly Fishing Magazine<br />

1 of 5 great prizes!*<br />

E FOR YOUR<br />

EE<br />

IPTION!<br />

1 Dozen Articulated Streamers<br />

*Drawing to be held April 15, <strong>2018</strong>

Fishing For A<br />

Get Hooked On Our Back Issues...<br />

G

ood Read?

Above: On an early spring morning, a crane aggressively defends its<br />

nest against an unwelcome intruder. Each spring, small populations<br />

of sandhill cranes stop over to nest in wetlands throughout the state,<br />

with some paying a visit to the Lake Helena Wildlife Management Area<br />

just north of Helena. Just a few frames captured an amazing glimpse<br />

into crane behavior— and certainly a memorable moment for this<br />

photographer! JASON SAVAGE<br />

Right: Sitting at just over 4,700 feet, Square Butte in Cascade County<br />

(not to be confused with the other Square Butte in Chouteau County)<br />

is a prominent landmark visible throughout the region just south of<br />

Great Falls. JASON SAVAGE<br />

Below: In Crow mythology, Old Man Coyote created people, animals,<br />

and the earth. In some versions, Old Man Coyote is also a trickster,<br />

and that characteristic has remained part of the coyote’s character.<br />

Trickster or not, the coyote relies on stealth to hunt, using all of<br />

its senses to locate prey. STEPHEN C. HINCH<br />

40

41

60

Left: A nonnative to Montana, California quail were introduced in the not so distant past and now<br />

thrive in the western part of the state.. JASON SAVAGE<br />

Far left: The Beartooth Highway is considered one of the most beautiful drives in the world.<br />

Starting in Cooke City, Montana, the road winds up through the mountains and crosses into Wyoming<br />

before dropping back down into Montana and the beautiful town of Red Lodge. The view from the top<br />

looks down into the heart of the Beartooth Mountains, a true Montana wilderness. STEPHEN C. HINCH<br />

Below: The viewpoint at Devil’s Canyon Overlook towers more than 1,000 feet above the water<br />

below in the Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area, established in 1966. The point where Bighorn<br />

Canyon and Devil’s Canyon come together is an incredible sight to behold. STEPHEN C. HINCH<br />

61

12

Above: Bald eagles can be found throughout<br />

Montana and are frequently seen around the<br />

state’s rivers and lakes. Fish compose a large<br />

part of their diet, and it’s not uncommon to<br />

see an eagle harassing an osprey to make<br />

it drop its catch. In winter, bald eagles hunt<br />

waterfowl. This eagle was perched in a tree<br />

above the Madison River looking for injured<br />

or ill mallards. STEPHEN C. HINCH<br />

Left: The Absaroka Mountains rise high<br />

above the Yellowstone River as it flows<br />

through Paradise Valley, a beautiful valley<br />

north of Yellowstone National Park and south<br />

of Livingston. Large herds of elk and deer<br />

reside in the valley, while eagles and osprey<br />

perch in cottonwoods above the river.<br />

At sunset, when conditions are right,<br />

the clouds and mountains light up in a<br />

multitude of colors. STEPHEN C. HINCH<br />

13

Jodi Monahan: Pain<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING<br />

“Patriotism Catch It“

ting For A Cause<br />

There are times in your life when things fall into place and if you allow<br />

yourself to follow your heart , passion and creativity it can lead you<br />

to a spectacular place. My son-in-law asked me to paint fish and from<br />

that I have entered the world of flyfishing and fly tying! I follow many avid<br />

fly tiers on instagram and wait for one of their flies to grab me. When they do<br />

I have to paint it to get it out of my mind. I’m well into over 100 fly paintings<br />

now.<br />

One of my favorite sources told me he was coming to Montana to volunteer<br />

with an organization called Warriors and Quiet Waters out of Bozeman.<br />

They match up a veteran with a wounded warrior and teach them to fly fish.<br />

When you are out on the water it’s a lot like when I paint, you can only think<br />

about that one thing. Your mind is clear of everything else. I decided to look<br />

into this organization and was so impacted and impressed. I took one of<br />

Son Tao caddis flies and painted it on a Lazy Susan. I had it delivered to the<br />

ranch while he was there volunteering for a week. I couldn’t stop thinking<br />

about the impact an organization like that<br />

makes in a community.<br />

Helping veterans enjoy the freedom that fly<br />

fishing gives you. I had an idea to use another of<br />

Son’s flies and changed it into a America flag. I<br />

choose a large canvas 36x36 to make the impact<br />

I wanted. On February 7th I delivered it to the<br />

Warriors and Quiet Waters Ranch to donate the<br />

Original to them. What a wonderful group of<br />

uplifting people that ingulf this special gift to the<br />

warriors who are blessed to make it out there.<br />

warriorsandquietwaters.org<br />

jodimonahanartistry.com<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

MONTANA FLYFISHING<br />

“Copper Beadhead”

“Floating The Hole”<br />

MONTANA FLYFISHING

Check us out<br />

on Facebook!<br />

facebook.com/mtflyfishmag<br />

Photo: Stacey Schad Randall