You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Adhrynn</strong><br />

A PRIMER<br />

By Scytheria<br />

<strong>Adhrynn</strong> /æˈθɹɪn:/ is a constructed (or artificial) language which exists for no purpose other than being pleasing to me,<br />

the author. It is not based on any natural language, and has an entirely a priori vocabulary in which words have been<br />

derived on aesthetic principles (which essentially means that they have been selected because I like the sound of them<br />

– it gets no more scientific than that).<br />

<strong>Adhrynn</strong> is not especially challenging, mainly because my purpose was to create a language that could actually be<br />

learned and spoken or written. There are, however, a few inflexion patterns and minor sound changes to learn, but<br />

these are quite regular in their own way and certainly no worse than many real languages. Perhaps the hardest aspect<br />

of <strong>Adhrynn</strong> is the four ‘tenses’ which kind of overlap the grammatical tenses used in English (and most other<br />

languages), and which express time in relative terms.<br />

The vocabulary of over 1000 root words is sufficient for <strong>Adhrynn</strong> to be used to speak or write creatively and variedly<br />

on most subjects, as long as those subjects are confined to pre-technological (Dark Age and earlier) Europe. By this, I<br />

mean that you will find words for oak trees, castles, knives, badgers and honey, but not for baobab trees, pagodas,<br />

computers, zebras and avocados.<br />

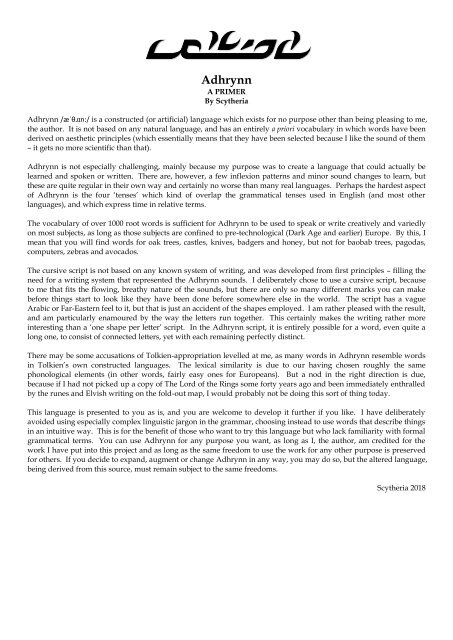

The cursive script is not based on any known system of writing, and was developed from first principles – filling the<br />

need for a writing system that represented the <strong>Adhrynn</strong> sounds. I deliberately chose to use a cursive script, because<br />

to me that fits the flowing, breathy nature of the sounds, but there are only so many different marks you can make<br />

before things start to look like they have been done before somewhere else in the world. The script has a vague<br />

Arabic or Far-Eastern feel to it, but that is just an accident of the shapes employed. I am rather pleased with the result,<br />

and am particularly enamoured by the way the letters run together. This certainly makes the writing rather more<br />

interesting than a ‘one shape per letter’ script. In the <strong>Adhrynn</strong> script, it is entirely possible for a word, even quite a<br />

long one, to consist of connected letters, yet with each remaining perfectly distinct.<br />

There may be some accusations of Tolkien-appropriation levelled at me, as many words in <strong>Adhrynn</strong> resemble words<br />

in Tolkien’s own constructed languages. The lexical similarity is due to our having chosen roughly the same<br />

phonological elements (in other words, fairly easy ones for Europeans). But a nod in the right direction is due,<br />

because if I had not picked up a copy of The Lord of the Rings some forty years ago and been immediately enthralled<br />

by the runes and Elvish writing on the fold-out map, I would probably not be doing this sort of thing today.<br />

This language is presented to you as is, and you are welcome to develop it further if you like. I have deliberately<br />

avoided using especially complex linguistic jargon in the grammar, choosing instead to use words that describe things<br />

in an intuitive way. This is for the benefit of those who want to try this language but who lack familiarity with formal<br />

grammatical terms. You can use <strong>Adhrynn</strong> for any purpose you want, as long as I, the author, am credited for the<br />

work I have put into this project and as long as the same freedom to use the work for any other purpose is preserved<br />

for others. If you decide to expand, augment or change <strong>Adhrynn</strong> in any way, you may do so, but the altered language,<br />

being derived from this source, must remain subject to the same freedoms.<br />

Scytheria 2018

Alphabet<br />

The <strong>Adhrynn</strong> alphabet, as transcribed into the Roman alphabet, contains just 16 letters: A B C D E F G H L M N O R<br />

S U and Y. The letter combinations DH, FH and GH behave like letters in their own right.<br />

<strong>Adhrynn</strong> is written from left to right, in a cursive manner. Each letter has up to four forms, depending where it<br />

appears in a word and how it connects to other words:<br />

Letter<br />

Isolate<br />

Connecting<br />

Right<br />

Connecting<br />

Left<br />

Connecting<br />

Left and Right<br />

a A. A a. a<br />

b b. b<br />

c c. c<br />

d d. d<br />

dh dh. dh<br />

e E. E e. e<br />

f F f<br />

fh fh. fh<br />

g g. g<br />

gh gh. gh<br />

h H. H h. h<br />

l L. L l. l<br />

m M m<br />

n N n<br />

o O. O o. o<br />

r R. R r. r<br />

s S s<br />

u U. U u. u<br />

y Y. Y y. y<br />

LIGATURES<br />

In the <strong>Adhrynn</strong> script, many letters connect to following letters via a ligature at the base. All letters have an isolate<br />

form, used when the preceding and following letters prohibit connection. Most letters (except m, n and s) connect to<br />

following letters. Many letters (except b, c, d, dh, f, fh, g and gh) connect to preceding letters. Many letters (a, e, h, l,<br />

o, r, u and y) can connect on both sides.<br />

Doubled letters (ll, mm, nn, rr and ss) are indicated by following a single instance of the letter with h. Since lh, mh,<br />

nh, rh and sh are not otherwise valid combinations, this causes no confusion.<br />

AmI.dh. A. ScronHe. Lam SE. fheanda.<br />

In the language definition that follows, we do not employ the <strong>Adhrynn</strong> script, choosing instead to render the words in<br />

their Roman transcription.

Phonology<br />

Although the number of distinct letters is relatively low, they combine to produce wide range of sounds. <strong>Adhrynn</strong><br />

spelling is almost entirely phonetic, but the value of some consonants varies somewhat depending on position within<br />

a word and on the surrounding letters. Most sounds are easy enough for Europeans to produce.<br />

CONSONANTS<br />

Letter Approximate Sound Value(s) IPA<br />

Usually b as in bend or above (is never word-final)<br />

b<br />

b<br />

In sb like the sp in spend, and in sbr like the spr in sprite<br />

p<br />

c Always like the k in king or the ch in ache (is never word final) k<br />

d<br />

dh<br />

Usually d as in dove, adage or sad<br />

In sd like the st in stop, and in sdr like the str in strong<br />

Usually like the th in though or rather<br />

Word-finally, and when preceded by s or followed by r, like the th in bath<br />

f Always like f in far or afar (is never word-final) f<br />

fh Always like v in voice or avoid (is never word-final) v<br />

g<br />

Usually g as in give, again or beg<br />

In ng, like the nkh of ankh (never the ng of sing)<br />

In sg like the sc of scar and in sgr like the scr of scratch, but both very guttural<br />

gh Only occurs at the end of root words, and is a guttural g sound ɣ<br />

h<br />

l<br />

m<br />

n<br />

r<br />

s<br />

In word-initial positions, before a vowel is a glottal stop<br />

When between vowels or in hr and hl, like the h in house or ahoy<br />

Otherwise modifies a preceding consonant (dh, fh, gh, lh, mh, nh, rh, sh)<br />

Usually like the l in look, alone or full<br />

When doubled in ll, is geminated and very long<br />

Usually like the m in milk, amen or ham<br />

When doubled in mm, is geminated and very long<br />

Can be found in a syllabic form at the end of a word in dhm and ghm<br />

Usually like the n in nook, anull or fin<br />

When doubled in nn, is geminated and very long<br />

Usually like the r in rook, around or fear<br />

When doubled in rr, is geminated and very long<br />

Often modifies the value of a preceding vowel<br />

Usually like the s in seek, assail or fuss<br />

When doubled in ss, is geminated and very long<br />

d<br />

t<br />

ð<br />

θ<br />

g<br />

x<br />

x<br />

ʔ<br />

h<br />

l<br />

l:<br />

m<br />

m:<br />

m̩<br />

n<br />

n:<br />

ɹ<br />

ɹ:<br />

s<br />

s:

VOWELS AND DIPHTHONGS<br />

<strong>Adhrynn</strong> has four main vowels, a, e, o and u, and a modifying semi-vowel y (which is also used as a vowel on its<br />

own). The letter r is used to lengthen vowel sounds without adding a rhotic quality to them.<br />

Letter Approximate Sound Value(s) IPA<br />

a<br />

Usually like the a in and or man<br />

In ar like the a in far<br />

In au like the au in autumn – the same as or, but longer<br />

In aur like the or in order but longer<br />

In ay like the igh in high<br />

In ayr like the ire in spire<br />

In word-final positions shortens to a schwa sound<br />

æ<br />

ɑː<br />

ɔː<br />

ɔːə<br />

aɪ<br />

aɪ.ə<br />

ə<br />

e<br />

o<br />

u<br />

y<br />

Usually like the e in end or men<br />

In ea like like the ia in fiat<br />

In ear like the ear in prearmed<br />

In eo like the aeo in aeon<br />

In eor like the eor in meteor<br />

In er like the ear in bear<br />

In ey like the ay in say<br />

In eyr like the ayer in sooth-sayer<br />

In word-final positions is virtually silent<br />

Usually like the o in off or fond<br />

In or like the or in order<br />

In ou like the the ou in loud<br />

In our like the ower in tower<br />

In oy like the oy in boy<br />

In oyr like the awyer in lawyer<br />

Usually like the oo in noose<br />

In ur like the ewer in skewer<br />

Usually like the i in ink or thin<br />

In yr like the eer in beer<br />

ɛ<br />

ɪːæ<br />

ɪːɑː<br />

ɪːɒ<br />

ɪːɔː<br />

ɛə<br />

eɪ<br />

eɪ.ə<br />

ø<br />

ɒ<br />

ɔː<br />

aʊ<br />

aʊ.ə<br />

ɔɪ<br />

ɔɪ.ə<br />

uː<br />

uːə<br />

ɪ<br />

ɪːə

ROOT WORDS<br />

<strong>Adhrynn</strong> is based on inflected root words, which can be nouns or verbs. Roots have a restricted structure which is<br />

best illustrated by the table below.<br />

Initial Consonant Medial Vowel Final Consonant<br />

r l a ea au aya ayo r l<br />

b sb sbr br bl e eya eyo<br />

c sc scr cr cl o eo ou oya oyo<br />

d sd sdr dr u d nd rd ld<br />

dh sdh sdhr dhr y dh ndh rdh ldh<br />

f sf sfr fr fl<br />

fh sfh sfhr fhr fhl<br />

g sg sgr gr gl gh ngh rgh<br />

h hr hl<br />

m sm m rm<br />

n sn n rn<br />

s sr sl s<br />

A root word is generally valid if it consists of an Initial Consonant, a Medial Vowel and a Final Consonant.<br />

Two further structural restrictions are colourised:<br />

1. Two salmon-cell consonants (R-coloured) cannot be used consecutively across the Initial-Final Consonants.<br />

Thus, combinations like *brar are invalid.<br />

2. Two mauve-cell consonants (L-coloured) cannot be used consecutively across the Initial-Final consonants.<br />

Thus, combinations like *blal are invalid.<br />

All roots are monosyllabic except those containing a dual-vowel (ea, eo, aya, ayo, eya, eyo, oya or oyo).<br />

WORD STRESS<br />

Dual-vowel roots are stressed on the syllable containing primary vowel, which is always the first one rather than the<br />

one following the y. Inflected roots retain their stress position. Regardless of any stress, vowels are always fullysounded,<br />

with the exception of final a or e.<br />

ROOT SOUND CHANGES<br />

When inflected, a root’s initial consonant sounds may change in predictable patterns. These always occur when a root<br />

is given a prefix ending with a vowel. There are only five known changes:<br />

b* mb*<br />

c* nc*<br />

d* nd* (but not dh* ndh*)<br />

f* mf * (but not fh* mfh*)<br />

g* ng*<br />

These changes are applied to the L-coloured or R-coloured variants of the same consonants. Thus, a+born amborn,<br />

and a+bron ambron.

Nouns<br />

<strong>Adhrynn</strong> nouns are inflected for plurality, duality, completeness or generality, possession and to turn them into other<br />

parts of speech, the most important of which is an attributive noun. There are no grammatical genders (unless<br />

inferred by the noun itself, like brother, sister, mother, etc. or found in certain suffixed noun forms), no cases and no<br />

specified articles, definite or indefinite.<br />

THE SINGULAR<br />

Countable roots are concrete things, complete concepts or completed actions (e.g. bears, languages, killings). In their<br />

root, uninflected form, they describe a single instance of a thing or action. Uncountable roots, in the singular, describe<br />

a quantity of a thing (e.g. water, blood, iron). Adjectival roots describe a quality (e.g. strength, bravery, greenness):<br />

nadh beauty lam (a) quantity of milk, (some) milk<br />

drogh (a) duty leom (a) flower<br />

mydh (a) king megh (a) girl<br />

bradh (a) table mour (a) man<br />

dhryn (a) language lordh strength<br />

droudh (a) dog ragh (a) quantity of blood, (some) blood<br />

heorn (an) eye radh (a) person<br />

fheand (a) sword sdhar (an) omen<br />

fhem nobility sfhraun (a) boy<br />

fles (a) bow scron (a) warrior<br />

gaurn (a) lake smaun (a) harp<br />

glean (a) hand sogh (a) quantity of wood, (some) wood<br />

gordh (a) bear sedh sweetness (of fragrance)<br />

gron (a) quantity of iron, (some) iron mas bravery<br />

hend (a) child mayan (a) mother<br />

hes greenness lerm (a) cup<br />

hron (a) brother mayos (a) quantity of water, (some) water

THE COMMON PLURAL<br />

The common plural form of a noun is made using slightly different modifications of each Final Consonant in the root:<br />

Final Consonant Changes (Common Plural)<br />

r rre<br />

l lle<br />

d dra nd ndra rd rda ld lda<br />

dh dhra ndh ndhra rdh rdha ldh ldha<br />

gh ghma ngh ngha rgh rgha<br />

m mme<br />

n nne<br />

s sse<br />

rm rma<br />

rn rna<br />

nadhra (some) beautiful ones lamme (some) quantities of milk<br />

droghma (some) duties leomme (some) flowers<br />

mydhra (some) kings meghma (some) girls<br />

bradhra (some) tables mourre (some) men<br />

dhrynne (some) languages lordha (some) strong ones<br />

droudhra (some) dogs raghma (some) quantities of blood<br />

heorna (some) eyes radhra (some) people<br />

fheandra (some) swords sdharre (some) omens<br />

fhemme (some) noble ones sfhraunne (some) boys<br />

flesse (some) bows scronne (some) warriors<br />

gaurna (some) lakes smaunne (some) harps<br />

gleanne (some) hands soghma (some) quantities of wood<br />

gordha (some) bears sedhra (some) sweet ones<br />

gronne (some) quantities of iron masse (some) brave ones<br />

hendra (some) children mayanne (some) mothers<br />

hesse (some) green ones lerma (some) cups<br />

hronne (some) brothers mayosse (some) quantities of water<br />

Note that adjectival roots describing a quality become nouns displaying that quality in the common plural. These are<br />

genderless, but can assume suffixes to indicate a male (-eya) or female (-aya). These suffixes replace the final a or e of<br />

the normal common plural. Thus, nadhra beautiful ones, nadhraya beautiful females, lordha strong ones, lordheya strong<br />

males.<br />

To form the singular of one of these words, it must be preceded by the number one: hem nadhraya a beautiful female,<br />

hem lordheya a strong male. These gender suffixes can also be used to add gender to non-qualitative nouns: hem<br />

droudhreya a male dog, hendraya female children.<br />

When specific numbers of a pluralised root are needed, a numeral precedes it. The common plural is used in all such<br />

cases, even if the number is one.<br />

hem gordha dar radhra las fheandra<br />

one bear two people three swords<br />

The complete number system is detailed in a later section.<br />

The common plural is used when one or more incident of a noun is being spoken or written about, but does not<br />

indicate the entire set of referenced instances or the entire set of instances (known and unknown). For these, the<br />

complete plural and general plural are used.

THE DUAL<br />

Things that naturally come in pairs (e.g. eyes, hands, parents) or any things there are exactly two of form plurals in a<br />

special way when they denote a full pair.<br />

Final Consonant Changes (Dual)<br />

r rres<br />

l lles<br />

d dras nd ndras rd rdas ld ldas<br />

dh dhras ndh ndhras rdh rdhas ldh ldhas<br />

gh ghmas ngh nghas rgh rghas<br />

m mmes<br />

n nnes<br />

s sses<br />

rm rmas<br />

rn rnas<br />

nadhras (both) beautiful ones lammes (both) quantities of milk<br />

droghmas (both) duties leommes (both) flowers<br />

mydhras (both) kings meghmas (both) girls<br />

bradhras (both) tables mourres (both) men<br />

dhrynnes (both) languages lordhas (both) strong ones<br />

droudhras (both) dogs raghmas (both) quantities of blood<br />

heornas (both) eyes radhras (both) people<br />

fheandras (both) swords sdharres (both) omens<br />

fhemmes (both) noble ones sfhraunnes (both) boys<br />

flesses (both) bows scronnes (both) warriors<br />

gaurnas (both) lakes smaunnes (both) harps<br />

gleannes (both) hands soghmas (both) quantities of wood<br />

gordhas (both) bears sedhras (both) sweet ones<br />

gronnes (both) quantities of iron masses (both) brave ones<br />

hendras (both) children mayannes (both) mothers<br />

hesses (both) green ones lermas (both) cups<br />

hronnes (both) brothers mayosses (both) quantities of water<br />

Like the plural, the dual can be given gender. The suffixes –eyas (male) and –ayas (female) are used, replacing the<br />

final as or es. Thus, massayas both brave females, fhemmeyas both noble males, gordhayas both female bears, etc.<br />

The dual can take a number, indicating the number of pairs, although this tends only to occur with body parts. las<br />

gleannes three pairs of hands, dar heornas two pairs of eyes.

THE COMPLETE PLURAL<br />

A special plural marks all instances of a root idea within the frame of reference of the speaker or writer.<br />

Final Consonant Changes (Complete Plural)<br />

r rren<br />

l llen<br />

d dran nd ndran rd rdan ld ldan<br />

dh dhran ndh ndhran rdh rdhan ldh ldhan<br />

gh ghman ngh nghan rgh rghan<br />

m mmen<br />

n nnen<br />

s ssen<br />

rm rman<br />

rn rnan<br />

nadhran (all of the) beautiful ones lammen (all of the) milk<br />

droghman (all of the) duties leommen (all of the) flowers<br />

mydhran (all of the) kings meghman (all of the) girls<br />

bradhran (all of the) tables mourren (all of the) men<br />

dhrynnen (all of the) languages lordhan (all of the) strong ones<br />

droudhran (all of the) dogs raghman (all of the) blood<br />

heornan (all of the) eyes radhran (all of the) people<br />

fheandran (all of the) swords sdharren (all of the) omens<br />

fhemmen (all of the) noble ones sfhraunnen (all of the) boys<br />

flessen (all of the) bows scronnen (all of the) warriors<br />

gaurnan (all of the) lakes smaunnen (all of the) harps<br />

gleannen (all of the) hands soghman (all of the) wood<br />

gordhan (all of the) bears sedhran (all of the) sweet ones<br />

gronnen (all of the) iron massen (all of the) brave ones<br />

hendran (all of the) children mayannen (all of the) mothers<br />

hessen (all of the) green ones lerman (all of the) cups<br />

hronnen (all of the) brothers mayossen (all of the) water<br />

Forced gender of the complete plural is formed with the suffixes –eyan (male) and –ayan (female), replacing the final<br />

an or en. Thus, nadhrayan all of the beautiful females, droudhreyan all of the male dogs, etc.<br />

The complete plural can, like the common plural, be preceded by numerals. When this occurs, the meaning of the<br />

numeral becomes “of a greater number of”:<br />

hem gordhan dar radhran las fheandran<br />

one of the bears two of the people three of the swords<br />

To show a part of a greater quantity, two numerals separated by the particle san are used. Without the second<br />

number, the implication is that all of the available number is being talked about:<br />

hem san las gordhan dar san las radhran dar san fheandran<br />

one of the three bears two of the three people all three of the swords<br />

To show a fractional quantity, the particle sydh is used instead:<br />

hem sydh las lammen<br />

one third of the milk

THE GENERAL PLURAL<br />

The final type of plurality, the general, invokes every possible instance of a noun. It is used when making sweeping<br />

statements of fact along the lines of all men are brave.<br />

Final Consonant Changes (General Plural)<br />

r rryn<br />

l llyn<br />

d dryn nd ndryn rd rdyn ld ldyn<br />

dh dhryn ndh ndhryn rdh rdhyn ldh ldhyn<br />

gh ghryn ngh nghyn rgh rghyn<br />

m mmyn<br />

n nnyn<br />

s ssyn<br />

rm rmyn<br />

rn rnyn<br />

Note that, unlike the common plural, dual and complete plural, -gh becomes -ghryn not, as might be expected, -<br />

ghmyn.<br />

nadhryn (all) beautiful ones lammyn (all) milk<br />

droghryn (all) duties leommyn (all) flowers<br />

mydhryn (all) kings meghryn (all) girls<br />

bradhryn (all) tables mourryn (all) men<br />

dhrynnyn (all) languages lordhyn (all) strong ones<br />

droudhryn (all) dogs raghmyn (all) blood<br />

heornyn (all) eyes radhryn (all) people<br />

fheandryn (all) swords sdharryn (all) omens<br />

fhemmyn (all) noble ones sfhraunnyn (all) boys<br />

flessyn (all) bows scronnyn (all) warriors<br />

gaurnyn (all) lakes smaunnyn (all) harps<br />

gleannyn (all) hands soghryn (all) wood<br />

gordhyn (all) bears sedhryn (all) sweet ones<br />

gronnyn (all) iron massyn (all) brave ones<br />

hendryn (all) children mayannyn (all) mothers<br />

hessyn (all) green ones lermyn (all) cups<br />

hronnyn (all) brothers mayossyn (all) water<br />

Forced gender of the general plural is formed with the suffixes –eyen (male) and –ayen (female), replacing the final yn.<br />

Thus, nadhrayen all beautiful females, droudhreyen all male dogs, etc.

THE DIMINUTIVE AND AUGMENTATIVE<br />

Nouns of all number can be given additional prefixes to form a diminutive or an augmentative. The diminutive prefix<br />

is y- and the augmentative is prefix is a-. The meaning of these forms differs by the type of noun affected.<br />

Qualitative nouns have their quality softened in the diminutive (but not denuded) whilst the quality is intensified in<br />

the augmentative. Other nouns have their size, status or positive qualities reduced in the diminutive, whilst bolstered<br />

in the augmentative. There is little consistency in meanings between different nouns, the meanings being largely<br />

assumed through long use:<br />

ynadh prettiness anadh great beauty, radiance<br />

yndrogh a petty, trivial duty androgh a great or onerous duty<br />

ymydh a petty king amydh a great king<br />

ymbradh a small table ambradh a large table<br />

ydhryn a minor language, dialect adhryn a major language<br />

yndroudh a small dog or puppy androudh a large dog or hound<br />

yheorn a tiny eye aheorn a large eye<br />

yfheand a short sword afheand a greatsword<br />

yfhem gentility, good manners afhem regality<br />

ymfles a short bow amfles a longbow<br />

yngaurn a pond angaurn a great lake or inland sea<br />

ynglean a small hand anglean a large hand<br />

yngordh a small bear or bear cub angordh a large bear<br />

yngron soft iron angron hard iron or steel<br />

yhend a little child or an infant ahend an older child<br />

yhes light/pale greenness ahes intense greenness<br />

yhron a younger brother ahron an older brother<br />

ylam watery milk alam cream, creamy milk<br />

yleom a small flower aleom a large flower or bloom<br />

ymegh a little girl amegh a young woman<br />

ymour a little man or a dwarf amour a large man or giant<br />

ylordh moderate strength alordh great strength<br />

yragh weak blood aragh strong blood<br />

yradh a minor people or tribe aradh a major people or race<br />

ysdhar a small omen or sign asdhar a great omen or portent<br />

ysfhraun a little boy asfhraun a young man<br />

yscron an unseasoned warrior ascron a great or experienced warrior<br />

ysmaun a small harp or lyre asmaun a large harp<br />

ysogh soft wood asogh hard wood<br />

ysedh subtle perfume asedh powerful perfume<br />

ymas moderate bravery amas fearlessness<br />

ymayan ‘mama’ (term of endearment) amayan a grandmother<br />

ylerm a small cup or vessel alerm a chalice<br />

ymayos a drop of water amayos a body of water

THE DEROGATORY<br />

Nouns can assume a derogatory prefix, su-, used to indicate that a noun is debased, broken, spoiled, diseased, weak,<br />

inferior or unpleasant. It does not denude a qualitative noun of its quality, but makes that quality undesirable in<br />

some way.<br />

sunadh<br />

sundrogh<br />

sumydh<br />

sumbradh<br />

sudhryn<br />

sundroudh<br />

suheorn<br />

sufheand<br />

sufhem<br />

sumfles<br />

sungaurn<br />

sunglean<br />

sungordh<br />

sungron<br />

suhend<br />

suhes<br />

suhron<br />

sulam<br />

suleom<br />

sumegh<br />

sumour<br />

sulordh<br />

suragh<br />

suradh<br />

susdhar<br />

susfhraun<br />

suscron<br />

susmaun<br />

susogh<br />

susedh<br />

sumas<br />

sumayan<br />

sulerm<br />

sumayos<br />

peculiar or unearthly beauty<br />

a pointless duty<br />

a corrupt, useless or tyrannical king<br />

a broken table<br />

a crude, primitive language<br />

a wretched dog, mongrel, mutt<br />

a diseased or blind eye<br />

a broken or blunt sword<br />

the arrogance of nobility<br />

a broken or inaccurate bow<br />

a stagnant or dried-up pond<br />

a crippled hand<br />

a weak or sickly bear<br />

poor quality iron<br />

a wretched child<br />

vile greenness<br />

a bastard brother<br />

spoiled or sour milk<br />

an ugly flower<br />

a wretched girl or whore<br />

a wretch or scoundrel<br />

ineffectual strength<br />

tainted or diseased blood<br />

a degenerate, primitive or sub-human<br />

a terrible omen or portent of doom<br />

a yob, thug, layabout or scoundrel<br />

a feeble warrior<br />

a broken or untuned harp<br />

rotten or worm-eaten wood<br />

overpowering pefurme<br />

foolhardiness<br />

a terrible mother<br />

a broken or leaking vessel<br />

stagnant or filthy water

POSSESSIVES<br />

<strong>Adhrynn</strong> denotes possession in six slightly different ways, depending on the relationship between two nouns. In<br />

English, the possessive apostrophe-s or the word of usually covers all of these.<br />

For alienable possession, where a thing is physically owned, the possessed noun is preceded by yn:<br />

fles yn scron<br />

the warrior’s bow<br />

fheand yn amydh<br />

the great king’s sword<br />

For anatomical possession, where a body part is possessed (but hardly owned), the possessed noun is preceded by sun:<br />

suheornas sun megh<br />

the girl’s blind eyes<br />

ragh sun amydh<br />

the great king’s blood<br />

For mutual possession, where a thing is not actually owned and the relationship between the two nouns is mutual,<br />

the possessed noun is preceded by sym:<br />

mayan sym sfhraun<br />

the boy’s mother<br />

sfhraun sym amayan<br />

the grandmother’s boy<br />

For qualitative possession, where a quality is exhibited, the possessed noun is preceded by em:<br />

mas em scron<br />

the warrior’s bravery<br />

amas em ysfhraun<br />

the little boy’s fearlessness<br />

For containment possession, where a noun contains or holds another noun, the possessed noun is preceded by hen:<br />

lerm hen lam<br />

a cup of milk<br />

ylerm hen alam<br />

a small cup of cream<br />

For component possession, where a noun is comprised or made of another noun, the possessed noun is preceded by<br />

ym:<br />

bradh ym sogh<br />

a wooden table<br />

fheand ym angron<br />

a sword of steel

ATTRIBUTIVE NOUNS<br />

A noun can modify the meaning of another noun in senses other than possession. When this occurs, the modifying noun is placed<br />

after the noun it modifies and is used in the attributive form. These behave more like adjectives than nouns, and in the case of<br />

qualitative nouns, can even be used as verbs.<br />

Final Consonant Changes (Attributive)<br />

r rr<br />

l ll<br />

d dru nd ndru rd rdu ld ldu<br />

dh dhm ndh ndhru rdh rdhu ldh ldhu<br />

gh ghm ngh nghm rgh rghm<br />

m mm<br />

n nn<br />

s ss<br />

rm rmu<br />

rn rnu<br />

nadhm<br />

droghm<br />

mydhm<br />

bradhm<br />

dhrynn<br />

droudhm<br />

heornu<br />

fheandru<br />

fhemm<br />

fless<br />

gaurnu<br />

gleann<br />

gordhm<br />

gronn<br />

hendru<br />

hess<br />

hronn<br />

lamm<br />

leomm<br />

meghm<br />

mourr<br />

lordhm<br />

raghm<br />

radhm<br />

sdharr<br />

sfhraunn<br />

scronn<br />

smaunn<br />

soghm<br />

sedhm<br />

mass<br />

mayann<br />

lermu<br />

mayoss<br />

concerning beauty, beautiful, to be beautiful<br />

concerning duty, dutiful, to be dutiful<br />

concerning kings, kingly, to be kingly<br />

concerning tables<br />

concerning language, linguistic<br />

concerning dogs, canine, dog-like, to be dog like<br />

concerning eyes, ocular<br />

concerning swords<br />

concerning nobility, noble, to be noble<br />

concerning bows<br />

concerning lakes<br />

concerning hands, hand-like, to be hand-like<br />

concerning bears, ursine, bear-like, to be bear-like<br />

concerning iron<br />

concerning children, childish, to be childish<br />

concerning greenness, green, to be green<br />

concerning brothers, fraternal, to be fraternal<br />

concerning milk, milky, to be milky<br />

concerning flowers, floral<br />

concerning girls, girlish, to be girlish<br />

concerning men, manly, to be manly<br />

concerning strength, strong, to be strong<br />

concerning blood, bloody, to be bloody<br />

concerning people<br />

concerning omens, portentous, to be portentous<br />

concerning boys, boyish, to be boyish<br />

concerning warriors<br />

concerning harps<br />

concerning wood<br />

concerning sweetness, fragrant, to be fragrant<br />

concerning bravery, brave, to be brave<br />

concerning mothers, maternal, to be maternal<br />

concerning cups<br />

concerning water, liquid, watery, to be liquid, to be watery<br />

An attributive can also be formed from nouns inflected by the diminutive, augmentative or derogatory prefixes.

The exact meaning of an attributive noun is not fixed, varying by context.<br />

scronne mass<br />

brave warriors<br />

leomme sedhm<br />

fragrant flowers<br />

gordh droudhm<br />

a dog-like bear<br />

mydh droghm<br />

a dutiful king<br />

mas scronn<br />

warrior bravery<br />

sedh leomm<br />

flower fragrance<br />

droudh gordhm<br />

a bear-like dog<br />

drogh mydhm<br />

a kingly duty<br />

An attributive noun can stand alone, without modifying another noun, as a title or appellation. Thus we see Mydhm<br />

(“The King”), Mayann (“Great Mother”), etc.<br />

Attributive nouns can be used with the diminutive, augmentative or derogatory prefixes, lessening or intensifying the<br />

attributes described:<br />

yleomme asedhm aleomme ysedhm leomme susedhm<br />

strongly-perfumed little flowers subtly-perfumed large flowers vilely-perfumed flowers<br />

It is worth noting that the name of this language, <strong>Adhrynn</strong>, is an attributive noun derived from dhrin language and<br />

used in the augmented form in a titular sense – The Great Language.<br />

<strong>Adhrynn</strong> tends not to construct long strings of adjectives (like a big beautiful green fragrant flower), although such<br />

sentences are entirely possible:<br />

aleom anadhm hess sedhm<br />

a big extremely beautiful green fragrant flower<br />

Unlike English, there is no particular order in which such attributives should be placed. The above could also be<br />

rendered as:<br />

aleom anadhm sedhm hess<br />

a big extremely beautiful fragrant green flower<br />

aleom hess anadhm sedhm<br />

a big green extremely beautiful fragrant flower<br />

aleom hess sedhm anadhm<br />

a big green fragrant extremely beautiful flower<br />

aleom sedhm anadhm hess<br />

a big fragrant extremely beautiful green flower<br />

aleom sedhm hess anadhm<br />

a big fragrant green extremely beautiful flower<br />

The careful use of the various plurals, diminutive, augmentative, derogatory and attributives can paint a very rich<br />

description with only a few words:<br />

yleommes anadhm ahess susedhm<br />

two small, extremely beautiful, bright-green but vilely-perfumed flowers<br />

Attributives and possessed nouns are assumed to modify the lead noun, not each other, although the particle ryn<br />

allows a logical break in a list of descriptors:<br />

fles ym sogh ordhm hess<br />

a strong green wooden bow<br />

fles ym sogh ryn ordhm hess<br />

a bow of strong, green wood

NUMBER<br />

We have already seen the cardinal numbers for one, two and three (hem, dar, las). <strong>Adhrynn</strong> employs an octal<br />

counting system:<br />

hem one hemme first<br />

dar two darre second<br />

las three lasse third<br />

sym four symme fourth<br />

gor five gorre fifth<br />

rem six remme sixth<br />

lon seven lhonne seventh<br />

sadh eight sadhrem eighth<br />

daradh sixteen daradhrem sixteenth<br />

lasadh twenty-four lasadhrem twenty-fourth<br />

syradh thirty-two syradhrem thirty-second<br />

goradh forty goradhrem fortieth<br />

resadh forty-eight resadhrem forty-eighth<br />

losadh fifty-six losadhrem fifty-sixth<br />

edhran sixty-four edhrannem sixty-fourth<br />

Numbers without specific names are formed by addition, starting with the highest multiple of eight:<br />

sadh hem nine sadh hemme ninth<br />

sadh dar ten sadh darre tenth<br />

sadh las eleven sadh lasse eleventh<br />

…<br />

…<br />

daradh sym twenty daradh symme twentieth<br />

…<br />

…<br />

lasadh gor twenty-nine lasadh gorre twenty-ninth<br />

…<br />

…<br />

syradh rem thirty-eight syradh remme thirty-eighth<br />

…<br />

…<br />

goradh lon forty-seven goradh lonne forty-seventh<br />

…<br />

…<br />

edhran gor sixty-nine edhran gorre sixty-ninth<br />

edhran rem seventy edhran remme seventieth<br />

edhran lon seventy-one edhran lonne seventy-first<br />

edhran sadh seventy-two edhran sadhrem seventy-second<br />

edhran sadh hem seventy-three edhran sadh hemme seventy-third<br />

…<br />

…<br />

edhran syradh sym a hundred edhran syradh symme hundredth<br />

Larger numbers are rarely used in contexts beyond counting stock, and in literature expressions like dar edhran two<br />

sixty-fours, edhran edhran sixty-four sixty-fours tend to mean ‘lots of’ or ‘vast amounts of’ rather than referring to<br />

specific quantities. This is the same way that English employs vague numerical expressions like several hundred, or<br />

hundreds upon hundreds.<br />

Adverbial numbers (once, twice, thrice, etc.) are formed from the cardinal number inflected in the same way as<br />

attributive nouns:<br />

hemm, darr, lass, symm, gorr, remm, lonn, sadhm…<br />

once, twice, thrice, four-times, five-times, six-times, seven-times, eight-times…

Acting rather like numbers, we also find cardinal sar (zero, no, none), leor (any), smean (few/little/scant), argand<br />

(many/lots/abundant), efhor (mostly, most), sgream (all, every), fhend (more), uran (less, fewer), sufhend (too<br />

many), suran (too few), and ordinal rounne (last, last few, final).<br />

As we have already seen, numbers precede the nouns they modify:<br />

Common Plural Complete Plural General Plural<br />

hem gordha dar gordhan hem gordhyn<br />

one bear two of the bears the one and only bear (in existence)<br />

hemme gordha darre gordhan hemme gordhyn<br />

the first bear the second one of the bears the first (ever) bear<br />

hem san las gordha dar san las gordhan hem san las gordhyn<br />

one of three bears two of the three bears one of the only three bears (in existence)<br />

hemme san las gordha darre san las gordhan hemme san las gordhyn<br />

the first of three bears the second of the three bears the first of the only three bears (in existence)<br />

sar gordha sar gordhan sar gordhyn<br />

no bears none of the bears no bear (that exists)<br />

leor gordha leor gordhan leor gordhyn<br />

any bears any of the bears any bear (that exists)<br />

smean gordha smean gordhan smean gordhyn<br />

a few bears a few of the bears few bears (that exist)<br />

argand gordha argand gordhan argand gordhyn<br />

a lot of bears many of the bears many bears (that exist)<br />

efhor gordha efhor gordhan efhor gordhyn<br />

most bears most of the bears most bears (that exist)<br />

sgream gordha sgream gordhan sgream gordhyn<br />

every bear all of the bears all bears (that exist)<br />

fhend gordha fhend gordhan efhor gordhyn<br />

more bears more of the bears more bears (of those that exist)<br />

uran gordha uran gordhan uran gordhyn<br />

fewer bears fewer of the bears fewer bears (of those that exist)<br />

sufhend gordha sufhend gordhan sufhend gordhyn<br />

too many bears too many of the bears too many bears (of those that exist)<br />

suran gordha suran gordhan suran gordhyn<br />

too few bears too few of the bears too few bears (of those that exist)<br />

rounne gordha rounne gordhan rounne gordhyn<br />

the last bear the last of the bears the last bear (of those that exist)<br />

It is important again to stress the difference between the plural, total and general. A common plural refers to any<br />

number of instances of a noun, but does not necessarily include every instance. The complete plural refers to every<br />

instance of a noun within the speaker or writer’s frame of reference, but again does not necessarily include every<br />

possible instance. The general plural, however, includes every possible instance. If you find three swords, you would<br />

use the common plural to say “I have found three swords”, and the implication is that there are other swords you have<br />

not found and know nothing about. If you were looking for three swords and found them all, you would use the<br />

complete plural to say “I have found all three of the swords”, and the implication is that there are other swords you may<br />

or may not have found, but they are not part of the three you were looking for. If you found all the swords in<br />

existence and there happened to be three of them, you would use the general plural to say “I have found all three<br />

swords”, and the implication is that there are no more swords to find anywhere.

PRONOUNS<br />

<strong>Adhrynn</strong> pronouns are rich and complex, containing vestiges of a case-system that is no longer used elsewhere.<br />

The First Person Singular (1PS) has masculine and feminine forms, and is declined for the agent (I), emphatic agent (I<br />

who), reflexive agent (I to myself), non-agent (me, to me) and possessive (my):<br />

ne/na<br />

arne/arna<br />

nennes/nannes<br />

nes/nas<br />

ennen/annen<br />

1PS agent: I (masculine/feminine)<br />

1PS emphatic agent: I who (masculine/feminine)<br />

1PS reflexive agent: myself (masculine/feminine)<br />

1PS non-agent: me (masculine/feminine)<br />

1PS possessive: my (masculine/feminine)<br />

The First Person Plural (1PP) has a neuter gender, but has collaborative (speaker and listener), inclusive (speaker,<br />

listener and third party) and exclusive (speaker and third party) forms. It is declined for the agent (we), emphatic<br />

agent (we who), reflexive agent (we to ourselves), non-agent (us, to us) and possessive (our):<br />

nyn/ynd/ynde<br />

arnyn/arn/arne<br />

nynnes/ynnes/yndes<br />

nys/ys/ysse<br />

nynnen/ynnen/ynden<br />

1PP agent: we (collaborative/inclusive/exclusive)<br />

1PP emphatic agent: we who (collaborative/inclusive/exclusive)<br />

1PS reflexive agent: ourselves (collaborative/inclusive/exclusive)<br />

1PP non-agent: us (collaborative/inclusive/exclusive)<br />

1PS possessive: our (collaborative/inclusive/exclusive)<br />

The Second Person Singular (2PS) has masculine and feminine forms, and is declined for the agent (you), emphatic<br />

agent (you who), reflexive agent (you to yourself), non-agent (you, to you) and possessive (your):<br />

fhen/fhan<br />

arfhen/arfhan<br />

fhennes/fhannes<br />

fhes/fhas<br />

fhenne/fhanne<br />

2PS agent: you (masculine/feminine)<br />

2PS emphatic agent: you who (masculine/feminine)<br />

2PS reflexive agent: yourself (masculine/feminine)<br />

2PS non-agent: you (masculine/feminine)<br />

2PS possessive: your (masculine/feminine)<br />

The Second Person Plural (2PP) has a neuter gender, but has immediate (you here) and indirect (you and others)<br />

forms. It is declined for the agent (you), emphatic agent (you who), reflexive agent (you to yourselves), non-agent (you, to<br />

you) and possessive (your):<br />

fhyn/afhyn<br />

arfhyn<br />

fhynnes/afhynnes<br />

fhys/afhys<br />

fhynne/afhynne<br />

2PP agent: you (immediate/indirect)<br />

2PP emphatic agent: you who (immediate and indirect)<br />

2PP reflexive agent: yourselves (immediate/indirect)<br />

2PP non-agent: you (immediate/indirect)<br />

2PP possessive: your (immediate/indirect)<br />

The Third Person Singular (3PS) has masculine, feminine and genderless genders. It is declined for the agent (he, she,<br />

this/that), emphatic agent (he who, she who, that which), reflexive agent (he to himself, her to herself, this/that to itself), nonagent<br />

(him, to him, her, to her, this/that, to this/that) and possessive (his, her, of this/that):<br />

len/lan/dhe<br />

adren/adran/ar<br />

lennes/lannes/dhenne<br />

les/las/dhes<br />

lenne/lanne/dhen<br />

3PS agent: he/she/this or that<br />

3PS emphatic agent: he who/she who/that which<br />

3PS reflexive agent: himself/herself/this or that to itself<br />

3PS non-agent: him/her/this or that<br />

3PS possessive: his/her/of this or that<br />

The Third Person Plural (3PP) has neuter and genderless genders. It is declined for the agent (they, these/those),<br />

emphatic agent (they who, these/those which), reflexive agent (they to themselves, these/those to themselves), non-agent (them,<br />

to them, these/those, to these/those) and possessive (their, of these/those):<br />

lyn/ydhe<br />

ardryn/yr<br />

lynnes/dhynne<br />

lys/dhys<br />

lynne/dhyn<br />

3PP agent: they/these or those<br />

3PP emphatic agent: they who/these or those which<br />

3PP reflexive agent: themselves/these or those to themselves<br />

3PP non-agent: them/these or those<br />

3PP possessive: their/of these or those<br />

The deployment of pronouns is covered in a later section on sentence structures.

Verbs<br />

<strong>Adhrynn</strong> verbs are marked for tense on a scale relative to the past, present and future of an event or state. There are<br />

four tenses in total, and each can be used to construct the active and passive voices and form infinitives.<br />

1. Predictive Tense - Describing the period before an event or state is instigated<br />

I was going to eat<br />

I am going to eat<br />

I will be going to eat<br />

He was to become strong<br />

He is to become strong<br />

He will become strong<br />

I was to come to love her<br />

I am to come to love her<br />

I will come to love her<br />

He was to become a great king<br />

He is to become a great king<br />

He will become a great king<br />

2. Incomplete Tense – Describing the period after an event or state is instigated but before realisation<br />

I had started to eat / I was eating<br />

I have started to eat / I am eating<br />

I will have started to eat / I will be eating<br />

He was becoming strong<br />

He is becoming strong<br />

He will be becoming strong<br />

I have started to love her<br />

I have started to love her<br />

I will have started to love her<br />

He was becoming a great king<br />

He is becoming a great king<br />

He will be becoming a great king<br />

3. Complete Tense – Describing the period after an event or state is realised<br />

I had eaten<br />

I have eaten<br />

I will have eaten<br />

He had become strong<br />

He has become strong<br />

He will have become strong<br />

He had come to love her<br />

He has come to love her<br />

He will have come to love her<br />

He had become a great king<br />

He has become a great king<br />

He will have become a great king<br />

4. Timeless Tense – Describing a period in which an entire event or state is instigated and realised<br />

I ate<br />

I eat<br />

I will eat<br />

He was strong<br />

He is strong<br />

He will be strong<br />

He loved her<br />

He loves her<br />

He will love her<br />

He was a great king<br />

He is a great king<br />

He will be a great king<br />

Verbs are inflected to show voice (active and passive) and sometimes with prepositional morphs. Tense information<br />

and negation is contained in a separate particle (called a marker) which usually sits between the agent and patient of<br />

the verb (or between the agent and the actual verb in the case of intransient verbs). The word order of clauses is agentmarker-(patient)-verb<br />

for the active voice and patient-marker-verb for the passive voice. In the active infinitive, the agent<br />

is completely dropped, and in the passive infinitive the patient is dropped. Ditransitive verbs are handled a little<br />

strangely, with the recipient usually acting as the patient (we will discuss this in depth in the next section).<br />

In the following examples of verb phrase formation, we render the <strong>Adhrynn</strong> sentences into English present tenses,<br />

although each example, of course, can be used to describe the past or future.

THE COPULA<br />

Markers without a verb form copulas, assigning the agent of the action as a noun or describing it with an attributive<br />

noun quality. The Predictive, Incomplete and Complete tenses intrinsically contain a sense of ‘becoming’ or<br />

transformation from one state to another, whilst the Timeless tense suggests an unchanging state (at least in the time<br />

period being talked or written about). The structure employed is agent-marker-verb (or marker-verb in the infinitive):<br />

Predictive Tense:<br />

1. He is going to become a great king len dhra amydh<br />

1. Neg. He is not going to become a great king len nadhra amydh<br />

1. Inf. To be going to become a great king dhram amydh<br />

1. Inf. Neg. To not be going to become a great king nadhram amydh<br />

1. He is to become strong len dhra lordhm<br />

1. Neg. He is not to become strong len nadhra lordhm<br />

1. Inf. To be going to become strong dhram lordhm<br />

1. Inf. Neg. To not be going to become strong nadhram lordhm<br />

The Predictive Tense can be given a sense of imminent instigation using the adverb edhra after the noun or attributive.<br />

Thus, len dhra amydh edhra he is soon going to become a great king or dhram lordhm edhra to soon be going to become<br />

strong. In negative statements, edhra provides a sense that instigation is not imminent: len nadhra amydh edhra he is<br />

not going to become a great king any time soon or nadhram lordhm edhra to not be going to become strong any time soon.<br />

Incomplete Tense:<br />

2. He is becoming a great king len agra amydh<br />

2. Neg. He is not becoming a great king len nagra amydh<br />

2. Inf. To be becoming a great king agram amydh<br />

2. Inf. Neg. To not be becoming a great king nagram amydh<br />

2. He is becoming strong len agra lordhm<br />

2. Neg. He is not becoming strong len nagra lordhm<br />

2. Inf. To be becoming strong agram lordhm<br />

2. Inf. Neg. To not be becoming strong nagram lordhm<br />

The Incomplete Tense can be given a sense of recent instigation using the adverb braya after the noun or attributive.<br />

Thus, len agra amydh braya he has just started to become a great king or agram lordhm braya to have just started to become<br />

strong. In negative statements, braya provides a sense that instigation has not yet occurred: len nagra amydh braya he<br />

has not yet started to become a great king or nagram lordhm braya to have not yet started to become strong.<br />

Another adverb, nafhray, gives the Incomplete Tense a sense that realisation is imminent: len agra amydh nafhray he<br />

has almost become a great king or agram lordhm nafhray to have almost become strong. In negative statements, nafhray<br />

gives a sense that, although the process is ongoing, realisation is far from being reached: len nagra amydh nafhray he<br />

is becoming more like a great king, but is currently far from being one or nagram lordhm nafhray to be becoming stronger, but<br />

to be far from strong at this time.<br />

Complete Tense:<br />

3. He has become a great king len adra amydh<br />

3. Neg. He has not become a great king len adranna amydh<br />

3. Inf. To have become a great king adram amydh<br />

3. Inf. Neg. To have not become a great king adrannam amydh<br />

3. He has become strong len adra lordhm<br />

3. Neg. He has not become strong len adranna lordhm<br />

3. Inf. To have become strong adram lordhm<br />

3. Inf. Neg. To have not become strong adrannam lordhm<br />

The Complete Tense can be given a sense of recent completion with the adverb sorn placed after the noun or<br />

attributive. Thus, len adra amydh sorn he has just/recently become a great king or adram lordhm sorn to have<br />

just/recently become strong. In negative statements, sorn gives a sense that the state has not yet been reached: len<br />

adranna amydh sorn he has not yet become a great king or adrannam lordhm sorn to not yet have become strong.

Timeless Tense:<br />

4. He is a great king len a amydh<br />

4. Neg. He is not a great king len anna amydh<br />

4. Inf. To be a great king am amydh<br />

4. Inf. Neg. To not be a great king annam amydh<br />

4. He is strong len a lordhm<br />

4. Neg. He is not strong len anna lordhm<br />

4. Inf. To be strong am lordhm<br />

4. Inf. Neg. To not be strong annam lordhm<br />

The Timeless Tense can be given a sense of enduring action using the adverb agrean after the noun or attributive.<br />

Thus, len a amydh agrean he is always great, as a king or am lordhm agrean to be, at all times, strong. In negative<br />

statements, it suggests the action is never performed: len anna amydh agrean he is never great, as a king or annam<br />

lordhm agrean to never, at any time, be strong.<br />

Another adverb, nagread, gives a sense of regularity: len a amydh nagread he is often great, as a king or am lordhm<br />

nagread to be, more often than not, strong. In negative statements is suggests the frequency of the action is low: len<br />

anna amydh nagread he is seldom great, as a king or annam lordhm nagread to seldom be strong.<br />

Any of the four tenses can be augmented with the adverb heord, which indicates that the action of the verb has<br />

undergone a change in potential. Thus, len dhra amydh heord he is now going to become a great king, len agra amydh<br />

heord he is now becoming a great king, len adra amydh heord he has now become a great king or len a amydh heord he is<br />

now a great king. In negative statements, it also implies a change in potential: len nadhra amydh heord he is no longer<br />

going to become a great king, len nagra amydh heord he is no longer becoming a great king and len anna amydh heord he is<br />

no longer a great king. The heord adverb is never used, however, with negative statements in the Complete Tense<br />

(which would make no sense, since a completed action is, by definition, unchangeable).

INTRANSITIVE VERBS<br />

Intransitive verbs (or transitive verbs used intransitively) have no patient. The structure employed is agent-markerverb<br />

(or marker-verb in the infinitive), and the verb is uninflected:<br />

Predictive Tense:<br />

1. The mother is going to weep mayan dhra creodh<br />

1. Neg. The mother is not going to weep mayan nadhra creodh<br />

1. Inf. To be going to weep dhram creodh<br />

1. Inf. Neg. To not be going to weep nadhram creodh<br />

1. He is going to kill len dhra sloud<br />

1. Neg. He is not going to kill len nadhra sloud<br />

1. Inf. To be going to kill dhram sloud<br />

1. Inf. Neg. To not be going to kill nadhram sloud<br />

1. She is going to come to love lan dhra meld<br />

1. Neg. She is not going to come to love lan nadhra meld<br />

1. Inf. To be going to come to love dhram meld<br />

1. Inf. Neg. To not be going to come to love nadhram meld<br />

The Predictive Tense can be given a sense of imminent instigation using the adverb edhra after the verb. Thus, mayan<br />

dhra creodh edhra the mother is soon going to weep, dhram sloud edhra to soon be going to kill or lan dhra meld edhra<br />

she is soon going to come to love. In negative statements, edhra provides a sense that instigation is not imminent: mayan<br />

nadhra creodh edhra the mother is not going to cry any time soon, nadhram sloud edhra to not be going to kill any time<br />

soon or lan nadhra meld edhra she is not going to come to love any time soon.<br />

The Incomplete Tense:<br />

2. The mother is weeping mayan agra creodh<br />

2. Neg. The mother is not weeping mayan nagra creodh<br />

2. Inf. To be weeping agram creodh<br />

2. Inf. Neg. To not be weeping nagram creodh<br />

2. He is killing len agra sloud<br />

2. Neg. He is not killing len nagra sloud<br />

2. Inf. To be killing agram sloud<br />

2. Inf. Neg. To not be killing nagram sloud<br />

2. She is coming to love lan agra meld<br />

2. Neg. She is not coming to love lan nagra meld<br />

2. Inf. To be coming to love agram meld<br />

2. Inf. Neg. To not be coming to love nagram meld<br />

The Incomplete Tense can be given a sense of recent instigation using the adverb braya after the verb. Thus, mayan<br />

agra creodh braya the mother has just started to weep, agram sloud braya to have just started to kill or lan agra meld braya<br />

she has just started to come to love. In negative statements, braya provides a sense that instigation has not yet occurred:<br />

mayan nagra creodh braya the mother has not yet started to weep, nagram sloud braya to have not yet started to kill or lan<br />

nagra meld braya she has not yet started to come to love.<br />

With nafhray, the Incomplete Tense is given a sense of imminent realisation: Thus, mayan agra creodh nafhray the<br />

mother has all but finished weeping, agram sloud nafhray to have almost finished killing or lan agra meld nafhray she has<br />

nearly come to love. In negative statements, nafhray gives a sense that, although the process is ongoing, realisation is<br />

far from being reached: mayan nagra creodh nafhray the mother is far from done weeping, nagram sloud nafhray to be<br />

far from having killed or lan nagra meld nafhray she is nowhere near having come to love.<br />

The Complete Tense:<br />

3. The mother has wept mayan adra creodh<br />

3. Neg. The mother has not wept mayan adranna creodh<br />

3. Inf. To have wept adram creodh<br />

3. Inf. Neg. To have not wept adrannam creodh

3. He has killed len adra sloud<br />

3. Neg. He has not killed len adranna sloud<br />

3. Inf. To have killed adram sloud<br />

3. Inf. Neg. To have not killed adrannam sloud<br />

3. She has come to love lan adra meld<br />

3. Neg. She has not come to love lan adranna meld<br />

3. Inf. To have come to love adram meld<br />

3. Inf. Neg. To have not come to love adrannam meld<br />

The Complete Tense can be given a sense of recent completion with the adverb sorn placed after the verb. Thus,<br />

mayan adra creodh sorn the mother has just finished weeping, adram sloud sorn to have just killed or lan adra meld sorn<br />

she has recently come to love. In negative statements, sorn gives a sense that the state has not yet been reached: mayan<br />

adranna creodh sorn the mother has not yet wept, adrannam sloud sorn to have not yet killed or lan adranna meld sorn<br />

she has not yet come to love.<br />

The Timeless Tense:<br />

4. The mother weeps mayan a creodh<br />

4. Neg. The mother does not weep mayan anna creodh<br />

4. Inf. To weep am creodh<br />

4. Inf. Neg. To not weep annam creodh<br />

4. He kills len a sloud<br />

4. Neg. He does not kill len anna sloud<br />

4. Inf. To kill am sloud<br />

4. Inf. Neg. To not kill annam sloud<br />

4. She loves lan a meld<br />

4. Neg. She does not love lan anna meld<br />

4. Inf. To love am meld<br />

4. Inf. Neg. To not love annam meld<br />

The Timeless Tense can be given a sense of enduring action using the adverb agrean after the verb. Thus, mayan a<br />

creodh agrean the mother weeps constantly, am sloud agrean to habitually kill or lan a meld agrean she eternally loves. In<br />

negative statements it suggests that the action is never performed: mayan anna creodh agrean the mother never weeps,<br />

annam sloud agrean to never kill, lan anna meld agrean she has never loved.<br />

Another adverb, nagread, gives a sense of regularity: mayan a creodh nagread the mother often weeps, am sloud<br />

nagread to regularly kill or lan a meld nagread she sometimes loves. In negative statements, it suggests that the<br />

frequency of the action is low: mayan anna creodh nagread the mother seldom weeps, annam sloud nagread to seldom<br />

kill or lan anna meld nagread she hardly ever loves.<br />

The Four Tenses can be augmented with the adverb heord, which indicates that the action of the verb has undergone<br />

a change in potential. Thus, mayan dhra creodh heord the mother is now going to weep, len agra sloud heord he is now<br />

killing, lan adra meld heord she has now come to love or len a sloud heord he now kills. In negative statements it also<br />

implies a change in potential: mayan nadhra creodh heord the mother is no longer going to weep, len nagra sloud heord<br />

he is no longer killing, lan anna meld heord she no longer loves. The heord adverb is never used, however, with negative<br />

statements in the Complete Tense (which would make no sense, since a completed action is, by definition,<br />

unchangeable).<br />

Infinitive Forms:<br />

In the infinitive, intransitive verbs usually drop their agent. The agent, however, can be retained if followed by the<br />

particle y:<br />

am creodh am mayan y creodh<br />

to weep for the mother to weep<br />

Pronouns, when employed in these structures, retain their case stubbornly (unlike English):<br />

adrannam sloud adrannam len y sloud<br />

to have killed for him [he] to have killed

TRANSITIVE VERBS<br />

Transitive verbs have an agent and a patient. In the infinitive, the agent is completely dropped. The structure<br />

employed is agent-marker-patient-verb (or marker-patient-verb in the infinitive), and the verb is uninflected:<br />

Predictive Tense:<br />

1. He is going to kill the bear len dhra gordh sloud<br />

1. Neg. He is not going to kill the bear len nadhra gordh sloud<br />

1. Inf. To be going to kill the bear dhram gordh sloud<br />

1. Inf. Neg. To not be going to kill the bear nadhram gordh sloud<br />

1. She is going to come to love him lan dhra les meld<br />

1. Neg. She is not going to come to love him lan nadhra les meld<br />

1. Inf. To be going to come to love him dhram les meld<br />

1. Inf. Neg. To not be going to come to love him nadhram les meld<br />

The Predictive Tense can be given a sense of imminent instigation using the adverb edhra after the verb. Thus, dhram<br />

gordh sloud edhra to soon be going to kill the bear or lan dhra les meld edhra she is soon going to come to love him. In<br />

negative statements, edhra provides a sense that instigation is not imminent: nadhram gordh sloud edhra to not be<br />

going to kill the bear any time soon or lan nadhra les meld edhra she is not going to come to love him any time soon.<br />

The Incomplete Tense:<br />

2. He is killing the bear len agra gordh sloud<br />

2. Neg. He is not killing the bear len nagra gordh sloud<br />

2. Inf. To be killing the bear agram gordh sloud<br />

2. Inf. Neg. To not be killing the bear nagram gordh sloud<br />

2. She is coming to love him lan agra les meld<br />

2. Neg. She is not coming to love him lan nagra les meld<br />

2. Inf. To be coming to love him agram les meld<br />

2. Inf. Neg. To not be coming to love him nagram les meld<br />

The Incomplete Tense can be given a sense of recent instigation using the adverb braya after the verb. Thus, agram<br />

gordh sloud braya to have just started to kill the bear or lan agra les meld braya she has just started to come to love him. In<br />

negative statements, braya provides a sense that instigation has not yet occurred: nagram gordh sloud braya to have<br />

not yet started to kill the bear or lan nagra les meld braya she has not yet started to come to love him.<br />

With nafhray, the Incomplete Tense is given a sense of imminent realisation: Thus, agram gordh sloud nafhray to have<br />

almost finished killing the bear or lan agra les meld nafhray she has nearly come to love him. In negative statements,<br />

nafhray gives a sense that, although the process is ongoing, realisation is far from being reached: nagram gordh sloud<br />

nafhray to be far from having killed the bear or lan nagra les meld nafhray she is nowhere near having come to love him.<br />

The Complete Tense:<br />

3. He has killed the bear len adra gordh sloud<br />

3. Neg. He has not killed the bear len adranna gordh sloud<br />

3. Inf. To have killed the bear adram gordh sloud<br />

3. Inf. Neg. To have not killed the bear adrannam gordh sloud<br />

3. She has come to love him lan adra les meld<br />

3. Neg. She has not come to love him lan adranna les meld<br />

3. Inf. To have come to love him adram les meld<br />

3. Inf. Neg. To have not come to love him adrannam les meld<br />

The Complete Tense can be given a sense of recent completion with the adverb sorn placed after the verb. Thus,<br />

adram gordh sloud sorn to have just killed the bear or lan adra les meld sorn she has recently come to love him. In<br />

negative statements, sorn gives a sense that the state has not yet been reached: adrannam gordh sloud sorn to have not<br />

yet killed the bear or lan adranna les meld sorn she has not yet come to love him.

The Timeless Tense:<br />

4. He kills the bear len a gordh sloud<br />

4. Neg. He does not kill the bear len anna gordh sloud<br />

4. Inf. To kill the bear am gordh sloud<br />

4. Inf. Neg. To not kill the bear annam gordh sloud<br />

4. She loves him lan a les meld<br />

4. Neg. She does not love him lan anna les meld<br />

4. Inf. To love him am les meld<br />

4. Inf. Neg. To not love him annam les meld<br />

The Timeless Tense can be given a sense of enduring action using the adverb agrean after the verb. am gordhyn<br />

sloud agrean to habitually kill bears [general] or lan a les meld agrean she eternally loves him. In negative statements it<br />

suggests that the action is never performed: annam gordhyn sloud agrean to never kill bears [general], lan anna les<br />

meld agrean she has never loved him.<br />

Another adverb, nagread, gives a sense of regularity: am gordhyn sloud nagread to regularly kill bears [general] or lan a<br />

les meld nagread she sometimes loves him. In negative statements, it suggests that the frequency of the action is low:<br />

annam gordhyn sloud nagread to seldom kill bears [general] or lan anna les meld nagread she hardly ever loves him.<br />

The Four Tenses can be augmented with the adverb heord, which indicates that the action of the verb has undergone<br />

a change in potential. Thus, len agra gordh sloud heord he is now killing the bear, lan adra les meld heord she has now<br />

come to love him or len a gordhyn sloud heord he now kills bears [general]. In negative statements it also implies a<br />

change in potential: len nagra gordh sloud heord he is no longer killing the bear, lan anna les meld heord she no longer<br />

loves him. The heord adverb is never used, however, with negative statements in the Complete Tense (which would<br />

make no sense, since a completed action is, by definition, unchangeable).<br />

Passive Voice:<br />

Transitive verbs can form the passive voice. The patient is fronted and the agent is moved after the verb and<br />

preceded by a particle, su. In addition, the verb is inflected:<br />

Final Consonant Changes (Passive)<br />

r rra<br />

l lla<br />

d dra nd ndra rd rda ld lda<br />

dh dha ndh ndhra rdh rdha ldh ldha<br />

gh gha ngh ngha rgh rgha<br />

m mma<br />

n nna<br />

s ssa<br />

rm rma<br />

rn rna<br />

Pronouns, in the passive, retain their cases stubbornly. In English, where the passive of I love her is she is loved by me,<br />

in <strong>Adhrynn</strong> the equivalent would mean her is loved by I:<br />

len dhra gordh sloud gordh dhra sloudra (su len)<br />

he is going to kill the bear<br />

the bear is going to be killed (by him)<br />

lan agra les meld les agra melda (su lan)<br />

she is coming to love him<br />

he is coming to be loved (by her)<br />

len agra gordh sloud heord gordh agra sloudra heord (su len)<br />

he is now killing the bear<br />

the bear is now being killed (by him)

In passive infinitives the patient is dropped, but the agent (who would not usually be mentioned in the active<br />

infinitive) can be introduced:<br />

adrannam les meld sorn adrannam melda (su lan)<br />

to have not yet come to love him<br />

to have not yet come to be loved (by her)<br />

Infinitive Forms:<br />

In the infinitive, transitive verbs usually drop their agent and, in bare infinitives, their patient. The agent, however,<br />

can be retained if followed by the particle y:<br />

am sloud<br />

am gordh sloud<br />

am len y sloud<br />

am len y gordh sloud<br />

am sloudra<br />

am sloudra su len<br />

am gordh y sloudra<br />

am gordh y sloudra su len<br />

to kill<br />

to kill the bear<br />

for him to kill<br />

for him to kill the bear<br />

to be killed<br />

to be killed by him<br />

for the bear to be killed<br />

for the bear to be killed by him<br />

Note the stubborn cases of the pronouns. In <strong>Adhrynn</strong>, a pronoun keeps the case of whatever it references irrespective<br />

of the sentence structure employed. As an illustration of this:<br />

English:<br />

<strong>Adhrynn</strong>:<br />

English:<br />

<strong>Adhrynn</strong>:<br />

The dog bit the man The dog bit him [patient] He [agent] was bitten<br />

The dog bit the man The dog bit him [patient] Him [patient] was bitten<br />

The girl loves flowers She [agent] loves them [patient] They [agent] are loved by her [patient]<br />

The girl loves flowers She [agent] loves them [patient] Them [patient] are loved by she [agent]<br />

This unusual (but logical) phenomenon does not, of course, extend to nouns (which are entirely uninflected for case).

PREPOSITIONAL VERBS<br />

Many intransitive or transitive verbs can have a directional nature, incorporating a preposition into the verb phrase to<br />

indicate purpose, destination or direction. Intransitive verbs with a preposition become semi-transitive (e.g. go go<br />

into (enter) or look look at), although the target is not regarded as the patient but as an oblique. Transitive verbs with<br />

a preposition become ditransitive (e.g. pour pour into). Ditransitive verbs are always prepositional in nature and<br />

have up to three arguments: the agent, the patient (who is the recipient or destination) and the oblique (the thing received<br />

or moved).<br />

Two prepositional particles are employed:<br />

Positive: used when the agent’s action directly changes the state of the patient, for movements made by the agent (or<br />

an object used by the agent) towards the patient or for when the patient senses something originating from the agent.<br />

In English, positive prepositions include for, to, towards, in, into, on, onto, etc. The positive prepositional particle is se,<br />

and this follows the verb and precedes the oblique:<br />

mydh a scron larn se fheand<br />

king MARKER warrior give POS.PREP sword<br />

the king gives a sword to the warrior<br />

megh a lerm hlend se lam<br />

girl MARKER cup pour POS.PREP milk<br />

the girl pours the milk into a cup<br />

lan a bradh gorn se lerm<br />

she MARKER table place POS.PREP cup<br />

she places the cup on the table<br />

sfhraun a meodh se megh<br />

boy MARKER sing POS.PREP girl<br />

the boy sings to the girl<br />

lan a dhand se gaurn<br />

she MARKER go POS.PREP lake<br />

she goes to (or into) the lake<br />

Negative: used when the agent’s action does not directly change the state of the patient, for movements made by the<br />

agent (or an object used by the agent) away from the patient and when the agent senses something caused by the<br />

patient. In English, negative prepositions include from, away, off, out, out of, down, down from, under, below, etc. The<br />

negative prepositional particle is sdru, and this follows the verb and precedes the oblique:<br />

mydh a scron hayard sdru fheand<br />

king MARKER warrior take NEG.PREP sword<br />

the king takes a sword from the warrior<br />

megh a hlend sdru lam<br />

girl MARKER pour NEG.PREP milk<br />

the girl pours the milk away<br />

lan a bradh gorn sdru lerm<br />

she MARKER table place NEG.PREP cup<br />

she places the cup under (or away from) the table<br />

lan a dhand sdru gaurn<br />

she MARKER go NEG.PREP lake<br />

she comes out of (or from) the lake<br />

mayan a creyan sdru sfhraun<br />

mother MARKER listen NEG.PREP boy<br />

the mother listens to the boy

As prepositions, se and sdru lack precision, but in most cases the position/direction can be inferred from context.<br />

Both, however, can be augmented by attributives acting as adverbs to refine the positional/directional meaning:<br />

lan a dhand rodru se gaurn<br />

she MARKER go centre-ATTRIB POS.PREP lake<br />

she goes to (or into) the centre of the lake<br />

lan a bradh gorn fremm sdru lerm<br />

she MARKER table place distance-ATTRIB NEG.PREP cup<br />

she places the cup far away from the table<br />

Prepositional phrases otherwise act entirely like as intransitive/transitive verbs, forming the tenses, infinitives and<br />

passive voice in the same manner:<br />

mydh a scron larn se fheand<br />

the king gives a sword to the warrior<br />

mydh a scron larn<br />

the king gives (something) to the warrior<br />

mydh a larn se fheand<br />

the king gives (somebody) a sword<br />

mydh a larn<br />

the king gives (something) (to somebody)<br />

am scron larn se fheand y mydh<br />

for the king to give a sword to the warrior<br />

am scron larn se fheand<br />

to give a sword to the warrior<br />

am scron larn y mydh<br />

for the king to give (something) to the warrior<br />

am scron larn<br />

to give (something) to the warrior<br />

am larn se fheand y mydh<br />

for the king to give a sword (to somebody)<br />

am larn se fheand<br />

to give a sword (to somebody)<br />

am larn y mydh<br />

for the king to give (something) (to somebody)<br />

am larn<br />

to give (something) (to somebody)<br />

scron a larna se fheand (su mydh)<br />

the warrior is given a sword (by the king)<br />

scron a larna (su mydh)<br />

the warrior is given (something) (by the king)<br />

am larna se fheand (su mydh) y scron<br />

for the warrior to be given a sword (by the king)<br />

am larna se fheand (su mydh)<br />

to be given a sword (by the king)

am larna (su mydh) y scron<br />

for the warrior to be given (something) (by the king)<br />

am larna (su mydh)<br />

to be given something (by the king)<br />

Ditransitive phrases can front the oblique in a ‘semi-passive’. This is formed by the structure se/sdru-oblique-markerpatient-verb-(su-agent).<br />

The normal passive verb ending is used, with the addition of –s:<br />

se fheand a scron larnas (su mydh)<br />

the sword was given to the warrior (by the king)<br />

se fheand a larnas (su mydh)<br />