In Praise of Holy Women

'Come to the Father' is the official journal of the Anglican Community of the Servants of the Will of God, Sussex, England, a contemplative monastic order for men and women founded in 1938. The aim of the journal is to maintain a dialogue between the Churches - East and West. This issue features articles on Evelyn Underhill, Julia DeBeausobre, Therese of Lisieux, Sister Joanna Reitlinger and Dorothy Day.

'Come to the Father' is the official journal of the Anglican Community of the Servants of the Will of God, Sussex, England, a contemplative monastic order for men and women founded in 1938. The aim of the journal is to maintain a dialogue between the Churches - East and West. This issue features articles on Evelyn Underhill, Julia DeBeausobre, Therese of Lisieux, Sister Joanna Reitlinger and Dorothy Day.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>In</strong> <strong>Praise</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Holy</strong><br />

<strong>Women</strong>

From Church <strong>of</strong> St Seraphim <strong>of</strong> Sarov, Paris: ‘If you remain in Me and<br />

I in you, you will bear much fruit; apart from Me you can do nothing.’<br />

(John 15:5)

Journal <strong>of</strong> the Community <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Servants <strong>of</strong> the Will <strong>of</strong> God<br />

CONTENTS<br />

'<strong>In</strong> <strong>Praise</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Holy</strong> <strong>Women</strong>'<br />

Father Superior’s Letter – Colin CSWG........................................................2<br />

<strong>In</strong>troduction to Articles......................................................................................4<br />

Page<br />

Iulia de Beausobre on Creative Suffering<br />

– Caroline Walton, Associate CSWG....................6<br />

Thérèse <strong>of</strong> Lisieux: her Human Face<br />

‒ Sr Mary Michael CHC................................................12<br />

Lift Up Your Hearts: the Spiritual Formation <strong>of</strong><br />

Nun-Iconographer, Joanna Reitlinger<br />

‒ Christopher Mark CSWG.........................................19<br />

Evelyn Underhill on St Paul the Mystic and the Monastic Ideal<br />

‒ Philip Gorski, Associate CSWG...........................39<br />

A Harsh and Dreadful Love: Dorothy Day's Witness to the Gospel<br />

‒ Jim Forest.........................................................................44<br />

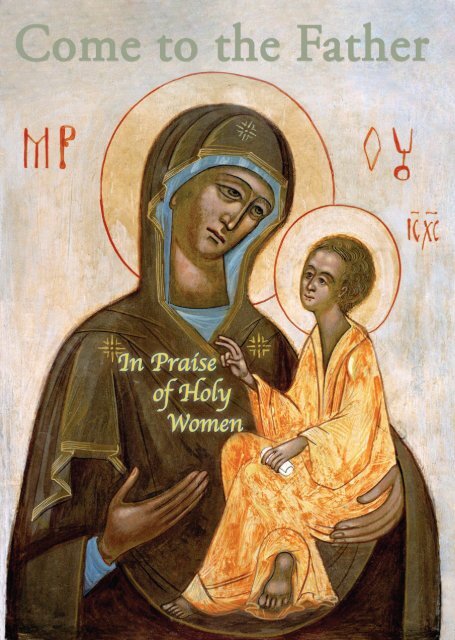

Cover: Theotokos (Virgin Mary) holding the Child Jesus at her side while pointing to<br />

Him as the source <strong>of</strong> salvation for humankind. A Hodigetria type <strong>of</strong> icon: "She who<br />

shows the Way"; <strong>In</strong> the Western tradition, this type <strong>of</strong> icon is frequently called Our<br />

Lady <strong>of</strong> the Way.<br />

To be included on our mailing list for Come to the Father, please send your name<br />

and address to father.peter@cswg.org.uk, or to the postal address on the back cover.<br />

Bulk orders: 5 copies for £10; 10 copies for £15.<br />

Epiphany 2018 No. 32

Dear Friends,<br />

FROM THE SUPERIOR<br />

Counting our blessings<br />

Earlier this year we decided to employ someone to cook for us. After various<br />

enquiries and advertisements, Louise Marcinkowski began as our cook in<br />

the middle <strong>of</strong> May. Louise is a pr<strong>of</strong>essional cook and lives in the village. She<br />

was previously employed as a cook at the Mc<strong>In</strong>doe plastic surgery and burns<br />

unit at the hospital in East Grinstead. She works Monday to Friday mornings,<br />

cooking our main meal and doing some preparation for supper. We, and our<br />

guests, are enjoying her delicious meals, beautifully cooked and presented.<br />

We are very thankful for all the care and thought that she puts into it. The<br />

kitchen and storeroom has been tidied up and at some stage we will need to<br />

make considerable improvements to the kitchen.<br />

We have changed the way we purchase our food and supplies, buying more<br />

locally and in smaller quantities. We hope this will reduce costs and avoid<br />

waste. When we have seen how this is working out financially, then we may<br />

see if we can find someone to do some housework and housekeeping, and<br />

also have some help in the garden when needed.<br />

Sheep may safely graze<br />

A local man heard that we had some open fields on our property and asked<br />

if he could put his flock <strong>of</strong> sheep in one <strong>of</strong> our pastures. Some adult sheep<br />

and their lambs duly arrived in April. Having eaten all the grass in the field<br />

by the barn, they then moved on to the field by the lake and having eaten all<br />

<strong>of</strong> that they have now moved back again into the barn field. It is certainly a<br />

very effective way <strong>of</strong> keeping the grass mown. The sheep seem content and<br />

it is good to have some animals in the place. We are not getting too attached<br />

to them, as the lambs are being reared for meat.<br />

Associates<br />

A dozen or so <strong>of</strong> our Associates met at the Monastery at the beginning <strong>of</strong><br />

May. On the first day we spent some time looking at two sermons <strong>of</strong> Father<br />

Gilbert Shaw. On the second day Dr Peta Dunstan spoke to us about the life<br />

<strong>of</strong> Father William <strong>of</strong> Glasshampton, revealing some interesting facts about<br />

his early life and exploring his decision to pursue a call to contemplative<br />

monastic life.<br />

We admitted Clive Holding, from Portslade, as a probationer Associate. We<br />

also admitted Paul Veitch as a probationer Associate on 7 May. Paul had been<br />

to stay with us on several occasions in the past, originally recommended by<br />

Associate, the late Father Michael Stagg. <strong>In</strong> more recent years, he has found<br />

it difficult to visit, undergoing treatment for cancer. After various courses <strong>of</strong><br />

treatment, which gave him some lengthy periods <strong>of</strong> remission, he accepted<br />

2

the news with great faith and courage that no more could be done. His visit to<br />

us in early May was cut short when his back became very painful so I admitted<br />

him as an Associate there and then, which he greatly appreciated. On his<br />

return home, his condition continued to deteriorate, and he died on 28 June.<br />

Some years ago, Paul started a contemplative prayer group in his parish which<br />

is now well-established, a lasting witness to his commitment to prayer and<br />

attentiveness to God.<br />

Fairacres<br />

<strong>In</strong> September, three <strong>of</strong> us – myself, Fr Peter and Br Christopher attended a<br />

Study Day on Fr Gilbert Shaw organised by the Sisters <strong>of</strong> the Love <strong>of</strong> God<br />

at Fairacres, Oxford, to commemorate the 50 th anniversary <strong>of</strong> his death. Fr<br />

Gilbert was Warden there for several years up until his death in 1967. The<br />

study day was a fitting tribute to his witness, with some papers given by the<br />

Sisters and by ourselves. The day concluded with a tour <strong>of</strong> the Sisters' new<br />

wing, and with recollections <strong>of</strong> earlier shared visits at Burwash.<br />

A testing time<br />

Brother Andrew is having a year out <strong>of</strong> the usual day-to-day life <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Community. He is living in one <strong>of</strong> the hermitages, coming to Lauds each day<br />

and the Eucharist on Sunday. He is continuing to look after the accounts, to<br />

deal with guest bookings and other administrative matters but otherwise is<br />

not as involved in the life <strong>of</strong> the Community as he used to be. This is to give<br />

him time and space to reflect on his vocation and what God wants him to be<br />

doing with his life. This is for a twelve-month period and it began just after<br />

Easter last year (2017). Please remember him in your prayers.<br />

Father John Patrick Buckingham<br />

Patrick made his first pr<strong>of</strong>ession in our Community on 8 December 1980<br />

and his life vows in 1984. He went with the first group <strong>of</strong> monks to the<br />

Monastery <strong>of</strong> Christ the Saviour at Hove in 1985. He left the Community and<br />

was received into the Roman Catholic Church in 1996, subsequently joining<br />

the Communities <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem and making his life pr<strong>of</strong>ession at All Saints<br />

1999. He was later ordained priest. <strong>In</strong> 2001, he went to the priory at Vezelay,<br />

which is on the pilgrimage route to Compostella and had a much-appreciated<br />

ministry welcoming pilgrims and hearing confessions. He went into hospital<br />

for a routine operation, but died unexpectedly on 25 July 2017. He was 82.<br />

He had kept in touch with us, always expressing his gratitude for all that he<br />

had received through his membership <strong>of</strong> our Community, and praying for<br />

the unity <strong>of</strong> the church.<br />

Isaac, Chae Choong Suk<br />

Isaac, a retired journalist, lives in Seoul in South Korea where his niece, Sister<br />

Jemma, is a member <strong>of</strong> the Community <strong>of</strong> St Francis. He wrote and asked if he<br />

could come and stay with us, in order to experience monastic life. He arrived<br />

3

at the beginning <strong>of</strong> September and stayed for two months. He valued the<br />

silence and the solitude as the setting for writing his next book. <strong>In</strong> addition,<br />

he supervised the picking <strong>of</strong> our large apple crop, doing an immense amount<br />

<strong>of</strong> work gently and quietly. It was a privilege to have him with us.<br />

Seekers<br />

Many religious communities nowadays provide the opportunity for people<br />

to live ‘alongside’ them, to explore a possible vocation to religious life or to<br />

provide the opportunity to share in a life <strong>of</strong> prayer whilst deciding on the<br />

next step. We have had the opportunity for people to be Seekers here since<br />

the early 1980's. We remain open to welcoming Seekers and enquiries from<br />

anyone wanting to live with us, from one month to six months or longer.<br />

Help<br />

<strong>In</strong> addition, we are always glad to receive any <strong>of</strong>fers <strong>of</strong> help if anyone would<br />

like to do some work in the place for a day or few days (accommodation<br />

free). Work in our library in particular is needed with help in thinning out<br />

books to make room for new books.<br />

We thank you as always for your prayers, gifts and donations, and assure you<br />

<strong>of</strong> our continuing prayers for you.<br />

Colin CSWG<br />

INTRODUCTION TO ARTICLES – ON HOLINESS<br />

Our theme in this current issue, <strong>In</strong> <strong>Praise</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Holy</strong> <strong>Women</strong>, opens itself <strong>of</strong><br />

course to the critical question: what is holiness? We are frequently warned<br />

in scripture to avoid unholiness: 1 Peter 2:1-2 for example: 'put away malice,<br />

deceit, hypocrisy, envy, slander' – and few <strong>of</strong> us would puzzle over what<br />

those things mean. Would practising the opposite – kindness, truthfulness,<br />

honesty, generosity, praise – make us holy? If so, there would have been no<br />

need for Christ to die on the Cross (Galatians 2:21). Being nice is a matter<br />

<strong>of</strong> social skills, not transformation. <strong>In</strong> the Christian sense holiness implies<br />

some sort <strong>of</strong> consummation: a ‘new heaven’, a ‘new earth’, a ‘new creation’;<br />

indeed, we are invited to participate in a ‘new reality’. This reality is not just<br />

the 'flipside' <strong>of</strong> the reality we already know. <strong>In</strong>herently and experientially it<br />

is joyful because it is endowed overwhelmingly with the truth <strong>of</strong> existence,<br />

but to attain it involves mental or physical suffering, or God forbid both.<br />

It is a matter <strong>of</strong> denying the desires and attractions with whch we are<br />

already overly familiar and ‘putting on’ the ‘Other’, a Person – the Christ,<br />

the Anointed One, the Messiah. Holiness is the outcome <strong>of</strong> our everdeepening<br />

relationship with that Person. For the Christian, this relationship<br />

4

is not an optional extra; it comes with the force <strong>of</strong> a commandment:<br />

'You shall be holy, for I am holy.' (1 Peter 1:16; cf Lev 11:45, 20:26, 21:8)<br />

<strong>In</strong> this issue, five authors – three Anglicans and two Orthodox – look at<br />

five contemporary women – one Anglican, two Roman Catholics and two<br />

Orthodox – all <strong>of</strong> whom aimed to fulfil the commandment to be holy. Only<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the five women has been canonised. The other four are simply ‘doers<br />

<strong>of</strong> the word, and not hearers only’ [James 1:22]. Caroline Walton on Julia de<br />

Beausobre, shows that attaining to holiness, one encounters what appears<br />

to be an insurmountable obstacle – that quintessential blockade called ‘the<br />

Cross’; it always involves suffering, but refusing to draw back from it, in<br />

what Beausobre calls ‘creative suffering’, leads surprisingly to such joy and<br />

freedom that the present reality begins to lose its grip on us. Like a woman<br />

giving birth – a classic metaphor for suffering – inescapable pain is followed<br />

by wondrous joy. Sister Mary Michael writing on Thérèse <strong>of</strong> Liseux, will not<br />

let us, however, exhaust women’s contribution with mere metaphors. ‘There<br />

is no respect for us poor, wretched women anywhere’, St Thérèse writes;<br />

‘And yet you’ll find the love <strong>of</strong> God much more common among women than<br />

among men, and the women during the Passion showed much more courage<br />

than the Apostles….’ <strong>In</strong> our feature article on Sister Joanna [Reitlinger], a<br />

nun-iconographer, who in her chosen pr<strong>of</strong>ession as an artist is continually<br />

repudiating self-importance, holiness begins essentially with an encounter<br />

with Christ. This marks the advent <strong>of</strong> a decisive winter thaw: the world<br />

loses its frozen grip on us, and we become aware, if only momentarily,<br />

<strong>of</strong> the other, Christ-sown, spiritual reality. Spiritual work then begins in<br />

earnest as we endeavour, with God's help, to reclaim the original image <strong>of</strong><br />

God in us (distorted by idolatry <strong>of</strong> self) as we now ‘strain forward’ (Phil<br />

3:13) to embrace Christ's likeness, while he in turn manifests to the world<br />

our uniqueness. Philip Gorski writes on the Anglican mystic and scholar,<br />

Evelyn Underhill, who, ‘speaking from pr<strong>of</strong>ound personal experience’ while<br />

swimming mightily against the academic, mainstream, theological currents<br />

<strong>of</strong> her time, develops the theme <strong>of</strong> contemplative prayer as practised by<br />

St Paul and continued by monastics and contemplatives down through<br />

the ages as the highway to holiness. ‘Holiness is not sinlessness’ is one <strong>of</strong><br />

Sergii Bulgakov's remarks, meaning we are not obliged to become holy<br />

before holiness takes up residence in those practicing ongoing repentance<br />

and service to fellow pilgrims, as Jim Forest demonstrates in his article<br />

on Dorothy Day, whose contemplation opened out in social action. A holy<br />

person, he tells us quite simply is someone ‘who in a remarkable way, shows<br />

us what it means to follow Christ.’<br />

Christopher Mark CSWG<br />

5

IULIA DE BEAUSOBRE ON 'CREATIVE SUFFERING'<br />

CAROLINE WALTON<br />

‘Iulia spoke <strong>of</strong> suffering<br />

as the most essential feature<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Christian religion –<br />

so <strong>of</strong>ten ignored or contradicted by liberal ideas.’ 1<br />

A poster in my local tube station advertises a book: 'You were not born to<br />

suffer,' which seems to sum up neatly the prevailing western secular attitude.<br />

Suffering is something to be pushed away, denied or, if it is too persistent,<br />

‘treated.’ It is rare to hear that, as the introduction to the first edition <strong>of</strong> Iulia<br />

de Beausobre’s essay Creative Suffering 2 asserts, ‘something can be made<br />

<strong>of</strong> suffering.’ Yet suffering is integral to the human experience and (in my<br />

case anyway) our most powerful catalyst for change. <strong>In</strong> the words <strong>of</strong> Father<br />

Sophrony, in its absence, man remains spiritually lazy, half-asleep, devoid <strong>of</strong><br />

Christ. 3<br />

Born Iulia Kazarina in 1893, de Beausobre grew up in an aristocratic Russian<br />

family. <strong>In</strong> 1917 she married a diplomat, Nikolai de Beausobre. Their only<br />

child died <strong>of</strong> starvation during the Civil War that followed the Bolshevik<br />

revolution. Both Iulia and Nikolai were arrested in 1932 and imprisoned<br />

and tortured in Moscow’s Lubianka prison. She was later sent to a gulag<br />

logging-camp; he was shot. De Beausobre was released after a year ‘on<br />

health grounds.’ Although her ‘freedom’ was severely circumscribed, she<br />

was able to get a message to an Englishwoman who had once been her nanny<br />

and who paid a ransom for her to leave the country. 4 Iulia settled in Britain<br />

where she became a writer and speaker, documenting her own experiences<br />

and helping people in the West enhance their understanding <strong>of</strong> Russian<br />

Orthodox spirituality. 5<br />

Creative Suffering opens by stating that the history <strong>of</strong> the Russian people<br />

is one <strong>of</strong> suffering, and <strong>of</strong> a particular type: 'the suffering <strong>of</strong> individuals<br />

endowed with a feeling for personal freedom so pr<strong>of</strong>ound as <strong>of</strong>ten to verge<br />

on the anarchic', who at the same time have been 'continually compelled to<br />

1<br />

Constance Babington-Smith, Iulia de Beausobre, A Russian Christian in the West (Darton,<br />

Longman and Todd 1983)<br />

2<br />

Iulia de Beausobre, Creative Suffering (Dacre Press 1940, republished by SLG press 1984)<br />

3<br />

Arch. Sophrony On Prayer (St Vladimir’s Press 1996).<br />

4<br />

<strong>In</strong> its drive to industrialise during those years, the USSR was anxious to acquire hard currency;<br />

later this form <strong>of</strong> ransom became impossible.<br />

5<br />

De Beausobre’s books include Flame in the Snow, A Life <strong>of</strong> Saint Seraphim <strong>of</strong> Sarov (Templegate<br />

1996) and a selection and translation <strong>of</strong> Russian Letters <strong>of</strong> Direction by Macarius, Staretz <strong>of</strong> Optino<br />

(St Vladimir’s Press 1975)<br />

6

live.... under a succession <strong>of</strong> despotisms resolutely bent on the destruction<br />

<strong>of</strong> that freedom.' 6 De Beausobre describes the co-existence <strong>of</strong> despotism<br />

and freedom in Orthodox Christianity, identifying 'two strains in Russian<br />

Christianity, the one which was formed by and from people <strong>of</strong> ascetic or<br />

disciplinarian temper, and the other by and from people <strong>of</strong> mystical temper<br />

(mystical in the widest sense <strong>of</strong> the word).'<br />

For De Beausobre, asceticism has a particular meaning and it is important<br />

to distinguish her definition from the commonly understood meaning <strong>of</strong> the<br />

word: it is 'a temper <strong>of</strong> mind that inhales fear and exudes fear.' She defines<br />

it in this disciplinary sense as the exercise <strong>of</strong> power in which the individual<br />

personality is crushed in the name <strong>of</strong> the ‘supreme good.’<br />

Those <strong>of</strong> the mystical temper have always been in the majority. 'Popular<br />

sympathy in Russia has always gone, and still goes, to any expression <strong>of</strong> this<br />

mystical temper, explicitly religious or not.' This temper may be seen, for<br />

example, in the popular veneration <strong>of</strong> St Seraphim <strong>of</strong> Sarov who rejected<br />

the power struggles <strong>of</strong> his monastery, and went to live for many years as a<br />

hermit in the forest.<br />

So how do these elements co-exist? What is the interplay between them?<br />

De Beausobre writes that for the first few centuries after the conversion<br />

<strong>of</strong> Russia to Christianity 'both tempers persisted side by side, each finding<br />

a Christian form <strong>of</strong> expression; during the whole <strong>of</strong> this time the deeper,<br />

mystical temper was more widespread; the articulate, ascetic temper more<br />

influential.' 7<br />

As a result <strong>of</strong> the Mongol invasion <strong>of</strong> 1240 there was a tightening <strong>of</strong> authority<br />

and hardening <strong>of</strong> convention in every area <strong>of</strong> life, until Russia reached its<br />

peak <strong>of</strong> brutal, disciplinary asceticism under Ivan the Terrible. Then in the<br />

seventeenth century, the reformer Peter the Great swept religious asceticism<br />

into the monasteries and out <strong>of</strong> everyday life, as he reformed and westernised<br />

the country.<br />

Asceticism was not confined to Christianity. '[It] reconquered its lost position<br />

in everyday life from outside the monasteries and outside the Church<br />

altogether.' This temper re-appeared as the revolutionary movement, or at<br />

least the strand that took power in 1917: 'The Bolshevik revolution...is in<br />

fact essentially disciplinarian and ascetic.'<br />

We need only look at Lenin, the arch-ascetic, the ruthless eliminator <strong>of</strong> dissent<br />

who shied away from music because he said it made him feel like talking<br />

6<br />

Unless otherwise stated, all quotes are taken from the Creative Suffering essay.<br />

7<br />

I would add that the Russian Christian mystical temper also absorbed elements <strong>of</strong> mystical<br />

paganism – sometimes referred to as dvoeveriye, a dual belief system – which still exists in this<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the world and is to some extent undergoing a resurgence.<br />

7

nonsense and caressing the people who could create such beauty in the<br />

midst <strong>of</strong> the filth <strong>of</strong> life. And today too, the teetotal, black-belt Putin presents<br />

a disciplinarian counterbalance to the anarchic ‘gangster capitalism’ that<br />

prevailed during the Yeltsin era and caused the impoverishment <strong>of</strong> so many.<br />

Paradoxically, however, the disciplinarians at times may have even fostered<br />

mysticism by throwing people back onto their inner resources to cultivate<br />

internal freedom, a freedom that would inevitably have an effect on those<br />

around them. De Beausobre and others such as Vladimir Lossky argue that<br />

this happened to the Church during the Soviet period. '<strong>In</strong> every place where<br />

the faith has been put to the test, there have been abundant outpourings<br />

<strong>of</strong> grace, the most astonishing miracles – icons renewing themselves... the<br />

cupolas <strong>of</strong> churches shining with light not <strong>of</strong> this world...' 8<br />

On the one hand countless thousands <strong>of</strong> Christians were persecuted during<br />

the decades <strong>of</strong> terror and repression that followed the Russian revolution<br />

<strong>of</strong> 1917. Theological schools, churches and monasteries were closed and<br />

religious publications prohibited. During Stalin’s terror, thousands <strong>of</strong> clergy<br />

and the faithful were shot or sent to camps. Yet on the other hand the<br />

Church survived underground, on both sides <strong>of</strong> the barbed wire. 9 It not only<br />

survived, it was purified in the crucible <strong>of</strong> repression.<br />

There are accounts <strong>of</strong> extraordinary experiences in Soviet prisons. Father<br />

Sophrony’s brother Nicholas was imprisoned in 1949. After his interrogator<br />

had finished questioning him, he picked up the phone and gave the order<br />

for his execution. But before the guards could come to take Nicholas away<br />

to shoot him in the back <strong>of</strong> the neck in the corridor, his interrogator fell ill<br />

with a suspected heart attack. Nicholas immediately called for help. It came<br />

in time, and the interrogator survived. He countermanded the order for<br />

execution, saying to Nicholas, ‘You saved my life. Now I will save yours.’<br />

When Father Sophrony asked his brother later how he had endured all his<br />

sufferings, Nicholas replied, ‘without prayer it is impossible.’ 10<br />

De Beausobre had gone through the interrogation process some 16 years<br />

earlier. Explaining in detail how she was able to survive, she writes that when<br />

one is tortured, there is only one way to save yourself: to fail to react. Then<br />

you will no longer be <strong>of</strong> interest to the inner sadism <strong>of</strong> the torturer, and will<br />

eventually be left alone. There are two ways to cease reacting: one is to render<br />

yourself completely unfeeling. But De Beausobre points out the dangers <strong>of</strong><br />

8<br />

Lossky, The Mystical Theology <strong>of</strong> the Eastern Church (St Vladimir’s Press 1976).<br />

9<br />

See in particular Father Arseny 1983-1973, Priest, Prisoner, Spiritual Father (trans. Vera<br />

Bouteneff, St. Vladimir’s Press 1998), Father Arseny – A Cloud <strong>of</strong> Witnesses, (trans. Vera<br />

Bouteneff, St. Vladimir’s Press 2001) and With God in Russia by Jesuit priest Walter J. Ciszek<br />

(Doubleday 1966).<br />

10<br />

Arch. Sophrony Letters to his Family (Stavropegic Monastery <strong>of</strong> St John the Baptist 2015)<br />

8

this path: 'as Berdyaev has remarked: "<strong>In</strong>ability to suffer sometimes proves<br />

to be the greatest evil <strong>of</strong> all"... if you lapse into such a condition, it is unlikely<br />

that you will ever get out <strong>of</strong> it without the help <strong>of</strong> a psychiatrist.'<br />

That state was very dangerous indeed. The gulag was full <strong>of</strong> inmates –<br />

usually ‘criminal’ prisoners – who had taken that path. 11 The other road<br />

was even harder. De Beausobre writes that this second way <strong>of</strong> coping<br />

with the sadism <strong>of</strong> torturers was excruciating: ‘It exacts <strong>of</strong> the victim who<br />

undertakes it a heightening <strong>of</strong> consciousness, which is inseparable from<br />

the pain that goes with any expansion <strong>of</strong> awareness.’ She explains that the<br />

victim has to make an intense effort to gain sympathetic insight into the<br />

situation, to be attentive to every detail <strong>of</strong> the moment, and to penetrate<br />

as far as possible into the minds <strong>of</strong> her torturers. She warns that this<br />

empathy must not veer into any sentimentality; you must avoid both selfpity<br />

and any absolution <strong>of</strong> your tormentors’ responsibility. 'All this is very<br />

hard. But the point is that once it is achieved, you realise that you have<br />

been privileged to take part in nothing less than an act <strong>of</strong> redemption...'<br />

Complete attention necessitated complete acceptance <strong>of</strong> the situation:<br />

no inner protest – ‘Why me?’ or ‘This is unfair; I am entirely innocent!’ –<br />

because resistance would mean absconding from the present. Acceptance<br />

meant surrendering to the reality <strong>of</strong> the moment, as Nicholas Sakharov had<br />

done by responding immediately his interrogator fell ill.<br />

This kind <strong>of</strong> attentiveness could only be attained through faith. De Beausobre<br />

stressed that it was important that the tortured belonged to the Church, so<br />

that they did not just think <strong>of</strong> themselves as poor or brave, lonely wretches<br />

but as members <strong>of</strong> the mystical body <strong>of</strong> Christ.... They alone can raise their<br />

harrowing experience from the level <strong>of</strong> a personal evil... and make it an<br />

impersonal enrichment, a universal good, a part <strong>of</strong> the redemptive work <strong>of</strong><br />

Christ through his mystical body – the Church.<br />

<strong>In</strong> her memoirs, de Beausobre recounts how she received Divine help during<br />

her periods <strong>of</strong> interrogation. She called it the voice <strong>of</strong> Peace which came to<br />

11<br />

<strong>In</strong> St Petersburg in the late 1990s I met a woman who had been an actor in a Siberian<br />

logging camp like the one to which De Beausobre had been sent. Tamara Petkevich suffered<br />

the consequences <strong>of</strong> the numbness, the spiritual deadness, against which De Beausobre<br />

warned. She described how female criminal prisoners had beaten her up as a ‘political’ – but<br />

a few weeks later they were weeping as she read them a story. “Perhaps you have to suffer<br />

a great deal in order to understand the effect <strong>of</strong> creative expression on the spirit,” Tamara<br />

Petkevich told me. “Only then do you truly appreciate how it enables you to survive an ordeal.<br />

The human psyche is capable <strong>of</strong> enormous transformation. It is only by living through this<br />

process that you appreciate it.” She saw her role as that <strong>of</strong> performing the equivalent <strong>of</strong><br />

cardio-pulmonary resuscitation on the prisoners – and on the guards too, by reminding them<br />

that beauty and emotion existed. And in doing this Tamara saved herself from lapsing into the<br />

condition <strong>of</strong> numbness and disconnection that De Beausobre warned against – a condition<br />

from which there is virtually no way back.<br />

9

her as she was summoned from her cell at nights: 'Peace. My peace be with<br />

you.' Later: 'The eyes <strong>of</strong> Peace are lighting up in my heart again. It is as though<br />

they were shining into my face, inundating it with light from the inside. The<br />

light seems to change the bones and muscles, it shines out through my eyes,<br />

my ears, the whole <strong>of</strong> my skull, changes the meaning <strong>of</strong> the world I see, the<br />

world I hear, the world I comprehend. And gives it up, thus illumined and<br />

transformed, to One who understands all things...'<br />

A few pages later, she is able to affirm that 'prayer resounding out <strong>of</strong> the<br />

depths <strong>of</strong> darkest pr<strong>of</strong>undity, out <strong>of</strong> the despairing marrow <strong>of</strong> human bones,<br />

is always answered fully.'<br />

De Beausobre’s point is that by overcoming the pain inflicted on them, the<br />

tortured not only make the criminality <strong>of</strong> the torturers less heinous, they<br />

bring something <strong>of</strong> beauty into the situation. If the tortured can make<br />

themselves invulnerable, they not only save themselves, they are actually<br />

performing an act <strong>of</strong> kindness to the torturers. 12<br />

By bringing the whole focus <strong>of</strong> her attention onto what was taking place both<br />

outside and within herself, de Beausobre attained an extraordinary depth <strong>of</strong><br />

serenity and even joy in having redeemed the evil deed. Through her faith,<br />

De Beausobre was able to transcend and transfigure her cir-cumstances. Her<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> inner peace became so deep and tangible that her torturers finally<br />

understood that she would not succumb.<br />

There was <strong>of</strong> course another form <strong>of</strong> surrender – surrender to the torturers<br />

by agreeing to join them. Many took that route and de Beausobre does<br />

not condemn them. <strong>In</strong> her memoirs 13 she describes Emma, a woman who<br />

shares her cell for a time, returning from an interrogation looking elated. De<br />

Beausobre realises what has happened and wishes that the future victims <strong>of</strong><br />

Emma’s betrayal will themselves learn to redeem that ugliness, and that the<br />

ugliness <strong>of</strong> the betrayal will be redeemed by something beautiful and human<br />

in her life out there.<br />

<strong>In</strong> the logging camp too, de Beausobre received assistance, both human – in<br />

the form <strong>of</strong> imprisoned nuns, and Divine. She – and others – were aware <strong>of</strong><br />

the presence <strong>of</strong> Saint Seraphim <strong>of</strong> Sarov, who had lived as a hermit in the<br />

surrounding forest: 'among the trees, an old cripple with an injured spine<br />

stands silently, his eyes two shining wells <strong>of</strong> blue.'<br />

To survive, she said, she had to make a ‘holy fool’ <strong>of</strong> herself, a figure that<br />

features large in Russian spirituality. De Beausobre emphasises that the<br />

12<br />

The case <strong>of</strong> Nicholas Sophrony, p 8 above, is another example. Upon hearing the order <strong>of</strong><br />

execution, he did not react outwardly; but inwardly he must have suffered inconsolably, even<br />

while calling for help for his executioner.<br />

13<br />

The Woman Who Could Not Die, Iulia de Beausobre (Gollancz 1948).<br />

10

‘fool’ is someone who deliberately chooses to participate in all the badness<br />

and degradation <strong>of</strong> society, because the Russian understanding is that<br />

good and evil are inextricably bound together. 'That is, to us, the greatest<br />

mystery <strong>of</strong> life on earth... evil must not be shunned, but first participated<br />

in and understood through participation, and then through understanding<br />

transfigured.' Iulia describes the vast numbers <strong>of</strong> religious men and women<br />

who were imprisoned in the gulag who made holy fools <strong>of</strong> themselves in<br />

accepting their torture at the hands <strong>of</strong> their ‘ascetic’ rulers.<br />

Much later, in the 1970's in England, De Beausobre carried her practice <strong>of</strong><br />

creative suffering into the process <strong>of</strong> dying. This she saw as a great process<br />

<strong>of</strong> sorting out <strong>of</strong> the ‘dieable from the ‘undieable,’ and for her the process<br />

could not have lasted too long. She regarded her carnal remains (by which<br />

she meant flesh, blood, bone, hair etc) as rags for cleaning up some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

pollutants <strong>of</strong> this world. She spoke <strong>of</strong> ‘our task – as Christians – to use our<br />

bodies <strong>of</strong> the Resurrection as purifiers’ <strong>of</strong> the earth that we increasingly<br />

pollute. 14 This idea she had absorbed from the nuns back in the logging<br />

camp in the 1930's.<br />

At the marginal hour, guide, Lord<br />

That my mortal remains decompose into cleansing substances,<br />

Which, in your hands<br />

Depollute your beautiful universe<br />

Polluted, in ignorance, not <strong>of</strong> choice<br />

By me, my ancestors and my contemporaries. 15<br />

* * *<br />

<strong>In</strong> her preface to Creative Suffering, Sister Rosemary SLG, says that Iulia de<br />

Beausobre’s approach is 'a reminder to Western Christians that suffering has<br />

a corporate as well as a personal aspect, and that this becomes redemptive<br />

within the mystical body <strong>of</strong> Christ.' It was certainly a reminder for me.<br />

Over the years I have learned to accept suffering as a necessary part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

process <strong>of</strong> repentance and transformation. To be alive and present to it as<br />

Iulia described, but within that, to constantly request Divine assistance. To<br />

ask: ‘What am I being shown here? What am I reacting to? What behaviour<br />

or belief system should I let go <strong>of</strong>?’ The response always comes, sooner or<br />

later. Painful as it may feel at the time, in hindsight the suffering invariably<br />

makes sense.<br />

De Beausobre, however, opens up horizons beyond the individual viewpoint,<br />

directing us towards new possibilities. One <strong>of</strong> these opened up to me recently,<br />

14<br />

Constance Babington Smith, op.cit..<br />

15<br />

A prayer Iulia composed as she was dying, quoted in Constance Babington Smith, ibid<br />

11

when I found myself wide awake at night with an inner knowledge that<br />

something terrible had happened nearby. I prayed, finally fell asleep, and<br />

awoke to the news <strong>of</strong> the Grenfell tower fire five miles away. A few days later<br />

I found myself awake at one in the morning. My state <strong>of</strong> inner disturbance<br />

told me something was happening and I kept vigil, praying till 6 am when<br />

I read the news <strong>of</strong> an attack on worshippers at a nearby mosque. At these<br />

times it feels as though something is praying through me, despite myself<br />

who would rather be fast asleep. If it is the spirit <strong>of</strong> peace then all I can do is<br />

try to follow Iulia’s example and be prepared to participate.<br />

<strong>In</strong> an era when, within the Anglican Church, the overtly mystical tends to be<br />

relegated to the margins, De Beausobre’s writings help to reconnect us to<br />

the essential Christian truth that our suffering may have a transfigurative<br />

role on a collective level. Her thesis gives flesh to St Seraphim Sarov’s famous<br />

dictum that if you ‘acquire the Spirit <strong>of</strong> Peace a thousand souls around you<br />

will be saved.’ Iulia was visited by the Spirit <strong>of</strong> Peace; through it she touched<br />

a great many souls, both here and in Russia.<br />

Caroline Walton, a CSWG Associate, is a pr<strong>of</strong>essional translator from Russian to English and the<br />

author <strong>of</strong> several books on Russia and the Soviet Union. She is currently working on a book on<br />

spirituality during the Soviet period, particularly in relation to war and catastrophe.<br />

THÉRÈSE OF LISIEUX: HER HUMAN FACE<br />

Sister Mary Michael<br />

<strong>In</strong> many ways Marie Françoise-Thérèse Martin (2 January 1873 –<br />

30 September 1897) could seem to be a spoilt child. She was the youngest<br />

daughter in a family <strong>of</strong> nine, five <strong>of</strong> whom, all girls, survived early childhood.<br />

Her mother died when she was four years old, and Thérèse was specially<br />

cherished by her father and her older sisters, but her lively personality was<br />

not eclipsed by them or the circumstances <strong>of</strong> her life.<br />

At the age <strong>of</strong> fourteen she had an ardent desire to enter the local Carmel at<br />

Lisieux there and then. Marie and Pauline, two <strong>of</strong> her sisters, had already<br />

done so, but this was not the reason for Thérèse to make her request. Only<br />

a direct call from God could have given her the courage to break the news to<br />

her father, apply to her local bishop and then travel to Rome to ask Pope Leo<br />

XIII himself to fulfil her wishes. She won the day, and on April 19th, 1888,<br />

Thérèse did indeed enter Carmel when only fifteen years old.<br />

She had already received many graces but in her humility, saw herself as least<br />

<strong>of</strong> all, a mere toy for the Child Jesus to play with, a little insignificant flower<br />

by comparison with God’s saints, the lilies and roses. But in her simplicity<br />

12

and innocence she was granted an immediate perception <strong>of</strong> the essence <strong>of</strong><br />

sanctity – the perfect fulfilment <strong>of</strong> the divine will in response to a vision <strong>of</strong><br />

God’s burning love. Thérèse stretched towards this directly and absolutely,<br />

without distraction or delay.<br />

The secrets <strong>of</strong> her life have come down to us in her famous l’Histoire d’une<br />

Âme (Story <strong>of</strong> a Soul), which Thérèse wrote at the request <strong>of</strong> her superiors, as<br />

well as in her poems and letters. Her outward life appeared unremarkable but<br />

her inner trials were costly indeed. At the age <strong>of</strong> 24 she died <strong>of</strong> tuberculosis.<br />

The sacrifice was complete.<br />

For one who has thus been apprehended by the burning fire <strong>of</strong> divine love<br />

there can in fact be no option but to respond to Love with love – love for God,<br />

for all mankind, for the whole <strong>of</strong> creation. Such all-embracing love is a sure<br />

mark <strong>of</strong> sanctity. St Thérèse <strong>of</strong> Lisieux is no exception.<br />

It would be a grave mistake to think that Christianity is world-denying,<br />

or, more especially, that a vocation to the enclosed religious life involves a<br />

disparagement <strong>of</strong> the human and the natural. Rather it is a concentration <strong>of</strong><br />

all the powers <strong>of</strong> body, mind and spirit on the one thing needful and so opens<br />

up the human person to the wholeness <strong>of</strong> reality.<br />

From early childhood Thérèse knew and loved God with all her heart and<br />

soul and revelled in the beauty <strong>of</strong> his creation. Such love spilled over to<br />

all with whom she had contact. <strong>In</strong> all this she was being prepared for her<br />

Carmelite vocation and she is in direct line with the life and teaching <strong>of</strong> St<br />

John <strong>of</strong> the Cross. But Thérèse and John alike went directly towards God, and<br />

the very speed <strong>of</strong> that journey entailed a discipline and asceticism that to<br />

unaccustomed eyes could seem like a disparagement <strong>of</strong> created things and<br />

<strong>of</strong> natural human affections. By paradox, however, they show us the infinite<br />

worth <strong>of</strong> all that God has made. A proper detachment teaches us to value<br />

God’s creation as a manifestation <strong>of</strong> his glory, to use and not abuse it, and to<br />

accept ourselves and one another with reverence and respect as sharers in it.<br />

Thérèse is manifestly a poet and an artist, as she herself admits in her<br />

writings, and which they themselves illustrate only too well. Imagery<br />

from nature, insights into human behaviour, humorous anecdotes abound,<br />

despite, in the Story <strong>of</strong> a Soul, the restrictions <strong>of</strong> style necessarily imposed in<br />

an autobiography written by a religious under obedience to her superiors.<br />

To the end <strong>of</strong> her short life, Thérèse was positive and outgoing, keeping<br />

secret the inner trials which go to the making <strong>of</strong> a saint. Her love <strong>of</strong> beauty<br />

and <strong>of</strong> people will come to express itself, but always in the last analysis with<br />

reference to God, their creator, source and goal.<br />

13

As a child <strong>of</strong> no more than six or seven, Thérèse was already discovering in<br />

her own delightful way the majesty <strong>of</strong> God in creation while also sensing<br />

that anything less than him was only second best:<br />

On the way home (on Sunday evenings) I would look up at the stars that<br />

shone so quietly, and the sight took me out <strong>of</strong> myself. <strong>In</strong> particular there<br />

was a string <strong>of</strong> golden beads, which seemed, to my great delight, to be in the<br />

form <strong>of</strong> the letter T. I used to show it to Papa and tell him that my name was<br />

written in heaven; then, determined that I wasn’t going to waste any more<br />

time looking at an ugly thing like the earth, I would ask him to steer me<br />

along and walk with my head well in the air, not looking where I was going<br />

– I could gaze for ever at that starry vault! 1<br />

A year or two later Thérése caught her first sight <strong>of</strong> the sea:<br />

I couldn’t take my eyes <strong>of</strong>f it, its vastness, the ceaseless roaring <strong>of</strong> the waves,<br />

spoke to me <strong>of</strong> the greatness and the power <strong>of</strong> God… I made a resolve that<br />

I would always think <strong>of</strong> our Lord watching me, and travel straight on in his<br />

line <strong>of</strong> vision till I came safe to the shore <strong>of</strong> my heavenly country. 2<br />

But she also remembered on the same occasion hearing a lady and gentleman<br />

ask her father if the pretty little girl was his daughter! Thérèse enjoyed the<br />

compliment since she didn’t think she was pretty at all.<br />

By the age <strong>of</strong> thirteen Thérèse felt herself to have grown up. She recalls some<br />

<strong>of</strong> the moving times she and her sister Céline (four years her senior) spent<br />

together. Both shared a deep love for God and <strong>of</strong> the natural world. Once<br />

again it is the night sky that Thérèse remembers:<br />

Those were wonderful conversations we had, every evening, upstairs in the<br />

room with a view. Our eyes were lost in distance, as we watched the pale<br />

moon rising slowly above the height <strong>of</strong> the trees. Those silvery rays she cast<br />

on a sleeping world, the stars shining bright in the blue vault above us, the<br />

fleecy clouds floating by in the evening wind ˗ how everything conspired to<br />

turn our thoughts towards heaven! 3<br />

We might be inclined to think that this preoccupation by Thérèse with the<br />

beauties <strong>of</strong> nature was something <strong>of</strong> a pious exaggeration, a reading back<br />

into the past <strong>of</strong> artificial sentiments self-consciously acquired later in<br />

the cloister. But this is hardly so. There is a natural freshness and poetic<br />

beauty about her writing, which somehow rings true. This is especially so<br />

when she describes her journey to Italy. Her over-riding objective was to<br />

gain permission from the Pope to enter Carmel at fourteen. But this did not<br />

prevent her from drinking in all she saw. We can feel her intense excitement<br />

as she crosses Switzerland by train.<br />

1<br />

Story <strong>of</strong> a Soul, St Therese <strong>of</strong> Lisieux Chapter VI Collins Fontana tr. Ronald Knox 1960<br />

2<br />

ibid., Chapter VII<br />

3<br />

ibid. Chapter XVI<br />

14

Rome was our goal, but there were plenty <strong>of</strong> experiences on the way there.<br />

Switzerland, where the mountain-tops are lost in cloud, with its graceful<br />

pattern <strong>of</strong> water-falls, its deep valleys where the ferns grow so high and the<br />

heather shows so red!... I was all eyes as I stood there, breathless at the<br />

carriage door. I wished I could have been on both sides <strong>of</strong> the compartment<br />

at once, so different was the scenery when you turned to look in the other<br />

direction. 4<br />

All the same her eyes were set upon the future and her vocation:<br />

‘Later on’, I thought, ‘when the testing time comes, I shall be shut up within<br />

the four walls <strong>of</strong> Carmel, and my outlook will be restricted to a small corner<br />

<strong>of</strong> (the) starry sky. Very well, then, I shall be able to remember the sights I’m<br />

looking at now, and that will give me courage.’ 5<br />

No doubt that was how it was, though monastic enclosure proved to be no<br />

obstacle to the development <strong>of</strong> her imaginative and creative powers. Not<br />

only did she write poetry and paint pictures but over and over again in the<br />

Story <strong>of</strong> a Soul, Thérèse uses imagery from the world <strong>of</strong> nature to illustrate<br />

her thought, <strong>of</strong>ten in a light-hearted and humorous way. For instance, in<br />

trying to explain that she didn’t care a scrap if other people stole her thunder<br />

by claiming her ideas as their own, she puts it like this:<br />

To suppose that this 'thought' belongs to me would be to make the same<br />

mistake as the donkey carrying the relics, which imagined that all the<br />

reverence shewn to the Saints was meant for its own benefit! 6<br />

Or again, there is the delightful picture <strong>of</strong> the novices who had been put<br />

under her care as a lot <strong>of</strong> playful sheep getting into mischief:<br />

Of course they (the novices) think I’m terribly strict with them, these lambs<br />

<strong>of</strong> your flock. If they read what I am writing now, they would say: “That’s<br />

all very well, but she doesn’t seem to mind it much, running about after us<br />

and lecturing us”. Oh dear, the spots I have had to point out on those white<br />

fleeces, the wool that gets caught in wayside hedges for me to retrieve!<br />

Never mind; let them say what they will, at the bottom <strong>of</strong> their hearts they<br />

know that I really do love them. 7<br />

There is a teasing, bantering tone about it all and one can well imagine the<br />

affection in which Thérèse would have been held by her charges, and the<br />

gratitude they must have felt, despite the heavy demands a saint in the<br />

making would have made on them.<br />

4<br />

ibid, Chap XIX<br />

5<br />

ibid, Chap XIX<br />

6<br />

ibid, Chap XXXV<br />

7<br />

ibid, Chap XXXVI<br />

15

Clearly, then, Thérèse shows that essential gaiety, that joyfulness which is<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the most significant marks <strong>of</strong> sanctity. Here too she is at one with<br />

her great predecessor in the Carmelite tradition, John <strong>of</strong> the Cross. But an<br />

outward lightness <strong>of</strong> touch in those close to God usually veils from those<br />

on the outside looking on, an inner costliness. <strong>In</strong> our own times, we have<br />

discovered with amazement that another namesake, Blessed Mother Teresa<br />

<strong>of</strong> Calcutta, suffered intense spiritual darkness and seeming lack <strong>of</strong> faith<br />

interiorly, while in Christ’s name spending her whole self in the service <strong>of</strong> the<br />

poor and destitute, and in cheerfulness <strong>of</strong> demeanour. Thérèse openly tells<br />

us <strong>of</strong> such trials too, and thus verifies for us both the reality <strong>of</strong> her sanctity<br />

but also her shared human frailty.<br />

The ‘little way’ <strong>of</strong> spiritual childhood was no mere pious observance.<br />

Community life <strong>of</strong>fers boundless opportunities for patience and acts <strong>of</strong><br />

genuine love, despite feelings <strong>of</strong> repugnances. Self-discipline, practised in<br />

simple ways, is part <strong>of</strong> the web and thrum <strong>of</strong> such daily life, schooling the<br />

monastic for even greater trials.<br />

I tried my best to do good on a small scale… all I could do was to take such<br />

opportunities <strong>of</strong> denying myself as came to me without the asking; that<br />

meant mortifying pride, a much more valuable discipline than any kind <strong>of</strong><br />

bodily discomfort…. 8<br />

Beneath all this, however, lay the deeper interior trials inevitable for those<br />

on the path to sanctity.<br />

<strong>In</strong> addition, one might have thought that the life <strong>of</strong> prayer would come easily<br />

to Thérèse, for in the conducive atmosphere <strong>of</strong> the cloister she had already<br />

tasted something <strong>of</strong> union with God. However, she had also reached out<br />

to embrace suffering and so was taken at her word. Any kind <strong>of</strong> spiritual<br />

consolation whatsoever was ultimately, denied her. Everything had to be<br />

done by faith rather than by feeling – and even this Thérèse accepted. She<br />

describes her pr<strong>of</strong>ession retreat as follows:<br />

It brought no consolation with it, only complete dryness and almost a sense<br />

<strong>of</strong> dereliction. Once more our Lord was asleep on the boat; how few souls<br />

there are who let him have his sleep out!… for my own part I am content to<br />

leave him undisturbed… Anyhow, my pr<strong>of</strong>ession retreat, like all the retreats<br />

I’ve made since, was a time <strong>of</strong> great dryness. 9<br />

Similarly, her reception <strong>of</strong> <strong>Holy</strong> Communion, unlike her first one, brought no<br />

consolation either and spiritual reading left her unmoved:<br />

8<br />

ibid, Chap XXVI<br />

9<br />

ibid, Chap XXVI<br />

16

Don’t think <strong>of</strong> me as buoyed up on a tide <strong>of</strong> spiritual consolation; my only<br />

consolation is to have none on this side <strong>of</strong> the grave. As for instruction,<br />

our Lord bestows that on me in some hidden way, without ever making<br />

his voice heard. I don’t get it from books, because I can’t follow what I<br />

read nowadays; only now and again, after a long interval <strong>of</strong> stupidity and<br />

dryness, a sentence I’ve read at the end <strong>of</strong> my prayer will stay with me…. 10<br />

It was the same with the Rosary, with the Offices in choir and with any<br />

help she might have had from those guiding her. Yet all this was only the<br />

background to more costly interior trials. On the eve <strong>of</strong> her pr<strong>of</strong>ession, for<br />

example, she had severe doubts about her vocation: ‘I saw life at Carmel as a<br />

desirable thing yet the devil gave me the clear impression it was not for me…<br />

darkness everywhere.’<br />

Then came that fatal Maundy Thursday when Thérèse began to spit blood.<br />

She knew she had not long to live. This filled her with immense supernatural<br />

joy, but by the end <strong>of</strong> Eastertide came the reaction, the last great spiritual<br />

darkness, the testing <strong>of</strong> her faith – ‘To appreciate the darkness <strong>of</strong> this tunnel<br />

you have to have been through it’, she wrote. Even thoughts <strong>of</strong> heaven became<br />

impossible and the darkness itself taunted her: ‘It’s all a dream this talk <strong>of</strong><br />

a heavenly country…. Alright, go on longing for death! But death will make<br />

nonsense <strong>of</strong> your hopes…’<br />

It is claimed that in her last illness, Thérèse asked to have her medication<br />

taken from her, lest she be tempted to put an end to things. With awe we<br />

contemplate the immense courage manifested in this Gethsemane-like<br />

experience, the last great temptation resisted, since in our time so many cry<br />

out for euthanasia as a basic human right.<br />

But to conclude on a quite different note: Thérèse speaks elsewhere with an<br />

equally contemporary voice. We may ask whether there is a latent feminism<br />

in her comments about the treatment <strong>of</strong> women in Italy? There is humour<br />

certainly:<br />

I still can’t understand why it is so easy for a woman to get excommunicated<br />

in Italy! All the time people seemed to be saying: “No, you mustn’t go here,<br />

you mustn’t go there, you’ll be excommunicated.” There is no respect for us<br />

poor wretched women anywhere. And yet you’ll find the love <strong>of</strong> God much<br />

more common among women than among men, and the women during the<br />

Passion showed much more courage than the Apostles… I suppose our Lord<br />

lets us share the neglect he himself chose for his lot on earth. <strong>In</strong> heaven,<br />

where the last shall be first, we shall know more about what God thinks. 11<br />

10<br />

ibid, Chap XXX<br />

11<br />

ibid, Chap XXII<br />

17

It was on heaven, <strong>of</strong> course, that Thérèse set her sights. Her love for her Lord<br />

was boundless so that she ardently desired to fulfil all vocations at once.<br />

Even Carmel itself didn’t seem enough sometimes:<br />

I seem to have so many other vocations as well! I feel as if I were called to<br />

be a fighter, a priest, an apostle, a doctor, a martyr…. 12<br />

This could almost be the voice <strong>of</strong> modern women searching for recognition<br />

and fulfilment. But Thérèse doesn’t rest there, she breaks through the male/<br />

female divide to the realm <strong>of</strong> divine love – the vocation which includes and<br />

transcends all others and is open to all. Perhaps here especially Thérèse, the<br />

Carmelite nun at prayer in the heart <strong>of</strong> the church, will rain down a copious<br />

shower <strong>of</strong> roses on us – the grace <strong>of</strong> discernment.<br />

Sr Mary Michael CHC is a member <strong>of</strong> the Community <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Holy</strong> Cross, an Anglican Benedictine<br />

order for women at Costock, in Leicestershire. She has written extensively on the saints and on the<br />

monastic life.<br />

12<br />

ibid, Chap XXX<br />

18

'LIFT UP YOUR HEARTS' –<br />

THE SPIRITUAL FORMATION OF<br />

NUN-ICONOGRAPHER SISTER JOANNA REITLINGER<br />

WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO HER WALL PAINTINGS<br />

'THE MYSTERY OF THE CHURCH'<br />

CHRISTOPHER MARK<br />

“Often, when doubts assail me while I am working – how<br />

much longer shall I be able to continue? – I take comfort (at any<br />

rate, I try to take comfort), in your words…that there remains work<br />

on the most important Icon – one’s soul – and I try to switch over to that<br />

work.…. [But] the mist hinders me. Only by God’s help!” (Sr Joanna, age 84,<br />

to her spiritual director, Protopriest Alexander Men, 6 June, 1982) 1<br />

On 31 May 1988, the 90-year old, deaf and blind, Russian woman who six<br />

years earlier penned the above lines, died full <strong>of</strong> days and joie-de-vivre in a<br />

wattle and daub hut in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. A great number <strong>of</strong> folk <strong>of</strong> all<br />

ages and from all walks <strong>of</strong> life flocked to her funeral. All spoke warmly <strong>of</strong><br />

this almost legendary nun-iconographer who had brought faith, light and joy<br />

into their lives with the small, personal icons she had painted in earnest and<br />

had given away in abundance – ‘little candles,’ they were called – radiant,<br />

iconographic glimpses <strong>of</strong> heaven that had brought them no little wonder,<br />

and had sustained them in prayer over many difficult years.<br />

Meanwhile, several thousand kilometres away, chief government<br />

representatives <strong>of</strong> the United Soviet Socialist Republic (USSR), who had<br />

maintained (along with their predecessors) that religion was the ‘opiate<br />

<strong>of</strong> the people,’ ironically, since Pascha (Russian Easter), had been ‘funding,<br />

promoting, endorsing’ 2 and even actively participating in the millennial<br />

celebrations <strong>of</strong> the conversion <strong>of</strong> the Rus to Christianity in 988 – a seminal<br />

event for the Russian people. This principally religious memorial, unfolding<br />

1<br />

Sister Joanna [Reitlinger]/Fr Alexander Men/Fr Sergii Bulgakov, The Wise Sky: Sr Joanna<br />

[Reitlinger]’s correspondence with Fr Alexander Men and Fr Sergii Bulgakov; quoted in<br />

Yudina, Tatiana, Bearers <strong>of</strong> Unfading Light, (hereafter, BOUL), tr. Mike Whitton, Bluestone<br />

Books, 2009, p 448; special thanks to Hélène Arjakovsky who rounded up all the Reitlinger<br />

articles from RSCM Messenger for me; I gave them to Mike Whitton for translation; he<br />

gave the translations to Tatiana Yudina who collated and significantly supplemented them<br />

with additional texts and commentary. This article is heavily indebted to her book and his<br />

translations for resource material.<br />

2<br />

cf. http://www.christianitytoday.com/history/issues/issue-18/soviet-union-celebrates-1000-years-<strong>of</strong>christianity.html<br />

accessed 1 July 2017.<br />

19

in St Petersburg (Leningrad, as it was called then; the city reclaimed its<br />

original title in 1991), and also in Moscow (not to mention Ukraine and<br />

elsewhere throughout Russia) – this religious memorial was to cap a series<br />

<strong>of</strong> political events that had unintentionally and inadvertently led to a rapid<br />

decline in communist Russia’s seventy-year experiment with atheism. Over<br />

the course <strong>of</strong> the next thirty years, tens <strong>of</strong> millions <strong>of</strong> people would openly<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ess their faith or come to faith 3 and thousands <strong>of</strong> churches and hundreds<br />

<strong>of</strong> monasteries would be rebuilt or reopened. (By contrast, State celebrations<br />

commemorating the hundredth anniversary <strong>of</strong> the Bolshevik Revolution<br />

– March-November 1917 – would be restrained almost to the point <strong>of</strong><br />

indifference.) As church bells once more resounded across the nation, one<br />

could easily imagine a faint smile crossing the lips <strong>of</strong> that old, Russian nun<br />

interred in Tashkent, for she was no stranger to irony and paradox.<br />

* * *<br />

A propensity for paradox is commonplace among Christians; however, in the<br />

case <strong>of</strong> Julia Nikolayevna Reitlinger, as she was known in the world, it was<br />

virtually the norm. <strong>In</strong>deed, this theme in her life was noted quite early by her<br />

spiritual director, Father Sergius Bulgakov, who remarked in a letter dated<br />

18 August 1931, about 11 years after their first encounter, that:<br />

Your fate touches and moves me. <strong>In</strong> its extraordinary paradox and sacrifice<br />

lies the seal <strong>of</strong> some kind <strong>of</strong> election. It is true, you do not always endure it.<br />

[T]hen … I feel [your burden as] heavy and terrible, since like you, I too am<br />

only human. Nonetheless, a life <strong>of</strong> sacrifice is most pleasing to God, not a<br />

successful one. Lift up your hearts to the Lord! 4<br />

Julia, who was born into an aristocratic family and was waited on by<br />

nannies, governesses and servants for nearly twenty years, served as cook<br />

and housekeeper for her spiritual teacher, S.N. Bulgakov and his family for<br />

twenty-two years; she, who as a child was physically weak with breathing<br />

problems, breathed in the spirit <strong>of</strong> Orthodoxy from her youth and lived to<br />

90; she, who since adolescence increasingly wrestled with deafness, was<br />

fluent in several languages, and taught them; she, who is <strong>of</strong>ten called ‘the<br />

first woman iconographer,’ worked at a vocation that traditionally was the<br />

exclusive domain <strong>of</strong> men 5 ; she, who after mastering traditional iconography,<br />

3<br />

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_<strong>of</strong>_the_Russian_Orthodox_Church; while those figures<br />

might represent only 15% <strong>of</strong> the total population (http://www.pewforum.org/2017/11/08/<br />

orthodox-christianity-in-the-21st-century/) this rapid resurgence is nevertheless remarkable if<br />

not miraculous.<br />

4<br />

BOUL, 131. ‘Lift up your hearts to the Lord,’ from the Eucharistic Prayer in the Liturgy <strong>of</strong> St<br />

John Chrysostom, but also to be found in most liturgies throughout the world.<br />

5<br />

Yazykova, I.K., Hidden and Triumphant: the underground struggle to save Russian iconography,<br />

tr. Paul Genier, Paraclete Press, 2010, p 72. ‘Modernity came late to Russia…Be that as it may, women<br />

now number among the most prominent <strong>of</strong> iconographers–both inside and outside Russia.’<br />

20

forged a richly innovative, iconographic style aimed to ‘reduce the image to its<br />

essentials,’ following precedents set by Andrei Rublev 6 and pre-14 th century<br />

iconographers; she, who though intelligent, tall and handsome and a woman<br />

<strong>of</strong> high standing, never married, becoming instead a nun, taking the name<br />

Sister Joanna (after John the Baptist, Friend <strong>of</strong> the Bridegroom), and lived not<br />

in a convent but in the world, under obedience in spite <strong>of</strong> her predilection<br />

for independence; she, who identified as an artist, came to understand<br />

iconography not only as an art form but also, more importantly, as theology<br />

(another field reserved exclusively for men), and herself as a theologian;<br />

she, who after a midlife crisis, disillusioned by a discrepancy between the<br />

Christian ideal and its actual practice, left the church and paradoxically, if<br />

not hypocritically, allowed herself, she writes enigmatically, to be ‘carried<br />

away in a way that did not fit with either my age or my status’ 7 ; she, who had<br />

devoted her life’s work to art, gave away her paints and brushes and took<br />

up work decorating silk shawls at a far flung factory in Uzbekistan; she, who<br />

then, in the twilight <strong>of</strong> her life, returned to the Church and under obedience<br />

took up icon painting once again, turning out more icons during the next 15<br />

years than she had in all the previous years <strong>of</strong> her life; she, who though in<br />

dire need financially, never accepted payment for her icons 8 , but freely gave<br />

them away to hundreds who requested them; she, who was forced into exile<br />

by Russian atheists, returned to her motherland (actually to Uzbekistan, a<br />

Russian satellite – another forced exile) and lived to see the first signs <strong>of</strong><br />

the downfall <strong>of</strong> the atheistic Russian government – the hidden life <strong>of</strong> Sister<br />

Joanna [Reitlinger], whose Christian witness coincided with some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

most turbulent religio-political events <strong>of</strong> the twentieth century might well<br />

stand out in sharp relief as an example <strong>of</strong> perseverance towards holiness in<br />

a world slow to discern the ‘signs <strong>of</strong> the times’.<br />

* * *<br />

What does Sr Joanna mean by referring to the soul as icon 9 and why is it<br />

‘the most important icon’? <strong>In</strong> Greek, ‘icon’ means ‘image’. <strong>In</strong> the book <strong>of</strong><br />

Genesis, it states categorically (as well as mystically), that human beings<br />

were created in the image and likeness <strong>of</strong> God:<br />

‘Then God said: Let us make human beings in our image (eikona), after our<br />

likeness. … God created humankind in his image (eikona); in the image<br />

(eikona) <strong>of</strong> God he created them; male and female he created them.’ (Genesis<br />

1:26-27).<br />

6<br />

Think <strong>of</strong> his ‘The Hospitality <strong>of</strong> Abraham,’ a complex image from Genesis 18 redacted to<br />

three angels, in what has become known as the icon <strong>of</strong> the ‘The <strong>Holy</strong> Trinity’.<br />

7<br />

Sister Joanna [Reitlinger], Autobiography, originally in Vestnik RSCM, No 159, 1990, pp 84-<br />

116; in BOUL, 330<br />

8<br />

Ibid, BOUL, 376<br />

9<br />

See excerpt at beginning <strong>of</strong> this article.<br />

21

According to the traditional Christian interpretation, the image and likeness<br />

<strong>of</strong> God in our original parents, rendered them loving, free and joyful, in<br />

communion with God and each other, innocent, unashamed (sinless), and<br />

(arguably – the fathers were by no means unanimous) immortal 10 ; and<br />

God was well pleased. Throughout the creation process, God saw all he had<br />

created was ‘good,’ but once human beings came into the picture, ‘everything<br />

was very good,’ (Genesis 1:31). That is, until the Fall (Genesis 3), when the<br />

image <strong>of</strong> God in these two ancestors underwent abrupt distortion. <strong>In</strong> The<br />

Undistorted Image, a literary portrait <strong>of</strong> the spiritual elder, Saint Silouan, by<br />

his disciple, Father Sophrony [Sakharov], Silouan’s ascetic struggles lead<br />

to the restoration in him <strong>of</strong> the original image <strong>of</strong> God that was in Adam. <strong>In</strong><br />

referring to the soul as icon, Sister Joanna is speaking similarly – that ‘work’<br />

<strong>of</strong> restoring that original image and likeness <strong>of</strong> God in herself; it is a ‘most<br />

important work,’ she tells us, in the sense that it is urgent: if she does not<br />

attend to it presently – ‘now’ (2 Corinthians 6:2b) – who will, and when?<br />

The Fathers understood this restorative process to be a work <strong>of</strong> co-operation:<br />

the soul is, as it were, in ‘training’ (ascesis), working together with God, who,<br />

in effect, draws the regions <strong>of</strong> darkness in the soul, dissipated by the passions<br />

and recurrent human self-will, back into a unity with himself for healing.<br />

Because the soul, created in fellowship and communion with God, had been<br />

negligent, distrustful, and disobedient (causing disfigurement in the soul),<br />

by means <strong>of</strong> the opposite disposition – humble obedience, dispassion and<br />

trust in God – the will <strong>of</strong> the soul is eventually realigned with God’s, and<br />

restoration in the image and likeness <strong>of</strong> God begins.<br />

How can we be certain that the ‘image <strong>of</strong> God’ is fundamental to our souls?<br />

Metropolitan Kallistos, in a typically lucid talk for the <strong>In</strong>stitute for Orthodox<br />

Christian Studies (IOCS), Cambridge, in 2015 11 , lists seven reference points<br />

for the existence <strong>of</strong> the image and likeness <strong>of</strong> God in human beings – attributes<br />

that do not figure prominently in other animals: the soul, he says, is a) God<br />

thirsty; b) Self aware; c) Freedom loving; d) Creative; e) Eucharistic; f) Social<br />

and g) A Pilgrim. He goes on to stress that without God humankind cannot<br />

become truly human:<br />

The first and obvious indication that we are in the image <strong>of</strong> God is that God<br />

is central to the human person [a nagging feature that does not go away<br />

even if we wish it would]. We are created in fellowship and communion with<br />

10<br />

Theological axioms are not meant to be evidence-based history. They attempt to provide<br />

a meta-narrative for why we are here, why we got to be the way we are and what we might<br />

legitimately aim for as we become truly human over time. To say that humankind was created<br />

immortal while obviously it is not currently the case, is merely a theological way <strong>of</strong> saying<br />

how far we have strayed from what we are really meant to become.<br />

11<br />

Metro. Kallistos [Ware], http://pemptousia.com/video/metropolitan-kallistos-ware-on-whatdoes-it-mean-to-be-a-person-part-two/<br />

22

God. If we refuse that fellowship and communion we deny our true self. If<br />

you affirm God, you affirm the human also. If you deny God, you deny the<br />

human also. [For example] in the Soviet Union, you had a systematic denial<br />

<strong>of</strong> God, but also, under Stalin, you had a systematic denial <strong>of</strong> the freedom<br />

and dignity <strong>of</strong> the human being. It was not a coincidence that these two<br />

things went together. Secularisation involves dehumanisation. The human<br />

animal is a God thirsty animal and a human being without God is not human,<br />

but subhuman… 12<br />

We will now endeavour to put this seven-point scheme to work, using it as a<br />

framework on which to hang certain events in Sister Joanna’s life. As Sister<br />

Joanna herself wrote to one <strong>of</strong> her spiritual children later in life:<br />

We <strong>of</strong>ten must do the thing we don’t want in the name <strong>of</strong> God…. We do not<br />

always know what is good for us and what is evil, but we must always be the<br />

prayer: ‘not mine, but thy will be done’…. You see, at times the most difficult<br />

and most necessary thing is to do the very thing you do not want.’ 13<br />

A life intent on holiness is the way <strong>of</strong> the Cross. Sister Joanna chose that way<br />

in order to allow her humanness to be refined, indeed, redefined – divinised<br />

into the original image and likeness <strong>of</strong> God. It is a ‘narrow way’ that brings<br />

dozens <strong>of</strong> practical and spiritual rewards, <strong>of</strong> which we will review but seven.<br />

God Thirsty<br />

Julia Nikolayevna from an early age identified God with joy and her encounter<br />

with joy was <strong>of</strong>ten derived from very simple things: ‘…[W]e grew up in an<br />

atmosphere <strong>of</strong> joie-de-vivre, which pervaded our devotional life as well.’ 14 A<br />

particularly vivid memory: Paschal night in St Petersburg, when ‘everything<br />

was alive and trembling,’ the whole city was ‘charged with paschal joy’<br />

while ‘peals <strong>of</strong> bells called back and forth [and] we [children] were ready to<br />

exchange Easter kisses with every last beggar….’ 15<br />