AKOSUA DUFIE VRS.pdf - Judicial Training Institute

AKOSUA DUFIE VRS.pdf - Judicial Training Institute

AKOSUA DUFIE VRS.pdf - Judicial Training Institute

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

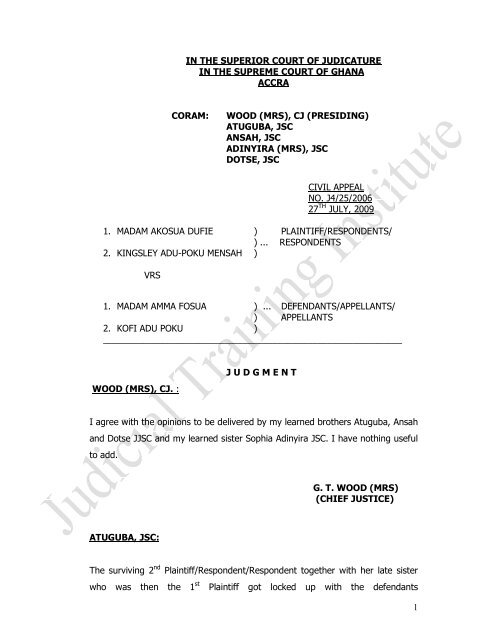

IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF JUDICATURE<br />

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF GHANA<br />

ACCRA<br />

CORAM: WOOD (MRS), CJ (PRESIDING)<br />

ATUGUBA, JSC<br />

ANSAH, JSC<br />

ADINYIRA (MRS), JSC<br />

DOTSE, JSC<br />

CIVIL APPEAL<br />

NO. J4/25/2006<br />

27 TH JULY, 2009<br />

1. MADAM <strong>AKOSUA</strong> <strong>DUFIE</strong> ) PLAINTIFF/RESPONDENTS/<br />

) ... RESPONDENTS<br />

2. KINGSLEY ADU-POKU MENSAH )<br />

<strong>VRS</strong><br />

1. MADAM AMMA FOSUA ) ... DEFENDANTS/APPELLANTS/<br />

) APPELLANTS<br />

2. KOFI ADU POKU )<br />

____________________________________________________________<br />

WOOD (MRS), CJ. :<br />

J U D G M E N T<br />

I agree with the opinions to be delivered by my learned brothers Atuguba, Ansah<br />

and Dotse JJSC and my learned sister Sophia Adinyira JSC. I have nothing useful<br />

to add.<br />

ATUGUBA, JSC:<br />

G. T. WOOD (MRS)<br />

(CHIEF JUSTICE)<br />

The surviving 2 nd Plaintiff/Respondent/Respondent together with her late sister<br />

who was then the 1 st Plaintiff got locked up with the defendants<br />

1

appellants/appellants in an estate dispute relating to the ownership of a house<br />

and two cocoa farms. Whilst the plaintiff claims that these are family properties<br />

the defendants claim they are all self-acquired properties of their late father and<br />

husband respectively.<br />

There are concurrent findings of fact on these matters in the High Court and<br />

Court of Appeal in favour of the plaintiff.<br />

It is trite law that an appellate court is not entitled to reverse concurrent findings<br />

of fact unless there are, in effect, strong legal or factual reasons to the contrary.<br />

It is also to be borne in mind that claims against the estate of a deceased person<br />

are to be viewed with caution and very cogent evidence is necessary to sustain<br />

the same.<br />

The plaintiff’s case is that when he was about leaving the country for Britain he<br />

handed over to the defendants’ late father and husband respectively a document<br />

covering a piece of land which later by substitution, became the plot on which<br />

the disputed house stands. He also owned a store and a beer bar which he left in<br />

the care of the same person, i.e. the late Kwaku Poku. He later instructed his<br />

said late brother to sell the store and beer bar and construct a house for him on<br />

the said plot of land.<br />

Ownership of the disputed house<br />

The courts below came to the conclusion that the house was not financed only<br />

by the late Kwaku Poku.<br />

One matter that did not receive critical attention by the courts below is the date<br />

of the construction of the house. The plaintiff is quite definite that the house was<br />

completed in June 1955 whereas exhibits 2 and 4 dated 9/5/1958 and 23/6/1958<br />

being an undertaking by Kwaku Poku to develop the said land within 2 years and<br />

a receipt for payment for the preparation of a development permit in respect of<br />

the said land, tend to show otherwise. Also at p. 42 of the record between lines<br />

1 to 4 the plaintiff admitted thus: “Yes I know that in the 1950s the<br />

colonial authorities insisted on strict compliance with building<br />

regulations. Yes without a development permit, you could not<br />

commence the development of any plot”. These pieces of evidence point to<br />

2

the high probability that the disputed house could not have been built in 1955 as<br />

contended by the plaintiff. This is especially so because as laid down in Atadi v<br />

Ladzekpo [1981] GLR 218 CA and Republic v Nana Akuamoah Boateng II,<br />

Ex parte Dansoah (1982-83) 2 GLR 913 S.C. documentary evidence should<br />

prevail over oral evidence. And in Guardian Assurance v Kyat Trading Store<br />

(1972) 2 GLR 48 C.A. at 55 Amissah J.A. (his brethren concurring), held that the<br />

supportive evidence of an opponent is as strong as the documentary evidence of<br />

the other party in proof of the latter’s case. However, as was held in Ahiabley v<br />

Dorgah (1984-86) 2 GLR 537 C.A., where documents support one party’s case<br />

as against the other, the court should consider whether the latter party was<br />

untruthful or truthful but with faulty recollection. In this case the trial judge saw<br />

the relevance of exhibit 2 only in terms of it being evidence of the acquisition of<br />

title to the property vel non. That exhibit was also relevant in the terms I have<br />

hereinbefore set out.<br />

The trial judge said of exhibit 2 at p. 136 of the record thus: “It is significant<br />

to note that the defendants did not produce for tender the allocation<br />

note. It is an undertaking allegedly made by the late Kwaku Poku.<br />

Whether the contents of Exhibit 2 are true or false is not clear on the<br />

evidence on the record”. Given the high evidential protein which documentary<br />

evidence contains, in the eyes of the law, the trial judge should have given<br />

cogent reasons for doubting the veracity of exhibit 2. The only discoverable<br />

reason is the non production in evidence of the allocation note. But given that<br />

the documents pertaining to grants of Kumasi lands were meticulously kept and<br />

processed by the Asantehene’s Lands Office as clearly shown by exhibits 2 and 4<br />

which clearly show that the lease document was yet to be prepared for execution<br />

by the parties, what does the allocation note matter? What could it in such<br />

circumstances have evidenced which exhibits 2 and 4 do not evidence? In any<br />

case I know of no law that mandatorily requires an allocation note. Even in<br />

Ghanaian popular parlance, it is a maxim that “Book no lie.”<br />

Applying the principle in Ahiabley v Dorgah, supra, could it be said in the face<br />

of exhibits 2 and 4 that the plaintiff is truthful but with a faulty recollection? The<br />

plaintiff in his evidence was so specific in terms of months and years and even in<br />

3

some cases of days of the week that he cannot be debited with faulty<br />

recollection. How then was he visiting a non-existent house in 1955? It stands to<br />

reason that since as per exhibits 2 and 4, not until as late as 9 th May 1958 the<br />

late Kwaku Poku was still battling for a development permit he could not have<br />

commenced let alone completed he said building much earlier.<br />

Furthermore the documents tendered in evidence tend strongly to show that the<br />

plot on which the disputed house stands was acquired in or around 1958. For<br />

several receipts show that the earliest demands and payments for ground rent<br />

date back only as far as 1958.<br />

Also the earliest demand notices and payments in respect of property rate, then<br />

known as general rate, are dated between 1963/64-1971/72. See pp 156-194 of<br />

the record of appeal. Again, on the evidence, the best known time when<br />

occupation of the house began, with tenants renting it is 1964 when PW3 rented<br />

some rooms and connected electricity to it and thereafter the 1 st late plaintiff<br />

herself came in there. If the house was completed in 1955 was it lying idle all<br />

this long?<br />

The Star Witnesses<br />

The courts below were highly captivated by the evidence of PWS 1 and 5 in<br />

particular. Their evidence however requires closer scrutiny.<br />

PW 1<br />

PW1’s evidence at p.45 between lines 31-36 is as follows: “One day I and my<br />

husband came to Kumasi from a cottage where we were farming. When<br />

we came the 2 nd plaintiff approached my husband and told him he had<br />

acquired a plot at Krofofrom and so he had come to see him build a house<br />

on the plot for him.” This evidence stands alone and is not even supported by<br />

the plaintiff himself. The nearest support for it is when the plaintiff at p. 30 of<br />

the record, in cross-examination and obviously as an afterthought, between<br />

lines 31-37 said thus: “I left the allocation sheet with my elder brother because I<br />

was leaving the country and I wanted him to use the proceeds of my shop<br />

to develop the land for me.” He does not even indicate where this took place.<br />

In any case from these two extracts the house was to be built not for the family<br />

but for the plaintiff.<br />

4

Again the evidence of PW1 on this issue lost compressure under cross-<br />

examination at p.46 lines 39-46 thus: “Q: When you said 2 nd plaintiff sent money<br />

to your husband, did he send the money from abroad.<br />

A: I cannot tell. What I know is that 2 nd plaintiff gave money and some<br />

documents to my husband.<br />

Q: Did you know what those documents were.<br />

A: No, what I know is that 2 nd plaintiff told my husband that he had<br />

acquired a plot.”<br />

Then at p.47 between lines 4-10 she continued thus: “Q: Did you know the<br />

purpose for which the money was given to your husband?<br />

A: What I know is that 2 nd plaintiff told my husband that he had acquired<br />

a plot at Krofofrom and that he should take the money and the<br />

documents and build a house for him.” One cannot fathom any consistency<br />

in such evidence. Nor should it be forgotten that though she admits that PW5<br />

used to visit them at the Abompe farm, she maintained that he used only to<br />

come for school fees but did not help on the farm. PW5 sharply challenges that<br />

evidence at p.78 lines 1 to 10 thus: “Q: Afua Manu (P.W.1) has told this court<br />

that no member of Kwaku Poku’s family assisted in the cultivation of the Abompe<br />

Cocoa Farm.<br />

A: If PW 1 said so, that is not correct because I was there and I<br />

assisted in the cultivation of that cocoa farm.” Naturally PW1 at least<br />

would have helped in the way he claims at p.74 of the record to have done.<br />

Between lines 20-21 thereof PW5 said: “I was assisting him to plant the<br />

cocoa trees.”<br />

It is quite clear that the courts below glossed over all these material<br />

considerations.<br />

PW 5<br />

In one breath at p. 74 lines 20-27 PW5 claims that only he and his grandmother<br />

assisted the late Kwaku Poku on his Abompe cocoa farm but in another breath at<br />

5

p.78 admits between lines 1 to 4 that Afua Manu (PW1) also assisted on that<br />

farm.<br />

At p. 73 of the record PW5’s trend of evidence clearly is that when plaintiff was<br />

leaving the country he entrusted the store to him PW5. He was running it and<br />

“using the proceeds of the sale to replenish the store.” Later he tries to<br />

rope in the late Kwaku Poku by saying that it was he that put him in charge of<br />

the store before the plaintiff left the country for Britain. But not even the plaintiff<br />

himself has said that before leaving the country he entrusted his store to the late<br />

Kwaku Poku!<br />

It is also amazing that though at p.34 of the record the plaintiff claimed between<br />

lines 29-30: “My daily earnings ranged between £25-£30. Yes, up to<br />

1952,” he could not even start developing his alleged plot of land before he left<br />

for Britain. His explanation at p. 40 between lines 23-24 that “I did not<br />

develop the plot before I left because I was busy working on my shop”<br />

is very strange indeed since PW5 his nephew in whose charge he left it before<br />

leaving for Britain was around till he also left for Britain in 1958. In any case it is<br />

difficult to see how a vibrant store business’ proceeds could only be used as PW5<br />

said to replenish it.<br />

The only indisputable evidence is the connection of water and electricity to the<br />

house by the deceased first plaintiff. But in my view such contributions to an<br />

already completed house can at best be a claim for restitution in equity but not<br />

co-ownership of the house. Even there she and her daughter enjoyed free<br />

accommodation in that house. This aside, it is incredible that the only two<br />

members of the family, particularly the plaintiff, who claims to have been the<br />

chief financier of the house, should have to leave that house especially as the<br />

plaintiff is quite clear that he has no other house.<br />

The courts below did not consider all these matters.<br />

Ownership of the Cocoa Farms<br />

This issue is the easiest to determine in this case. It is quite clear on the<br />

evidence that the Abompe farm is the earlier of the two farms and indeed the<br />

thrust of the evidence is that the second farm (the Siiso farm) is an offshoot of<br />

6

the Abompe farm. It therefore follows that if the earlier one is not family<br />

property then the Siiso farm cannot be family property.<br />

PW1, testified at p. 45 of the Record between lines 31 and 37 thus: “One day I<br />

and my husband came to Kumasi from a cottage where we were<br />

farming…” Again at p.46 between lines 16-26 she said: “Yes I took part in<br />

cultivating the Abompe farm. I was the only one who assisted to cultivate the<br />

Abompe farm- no member of my husband’s family assisted in cultivating the<br />

Abompe farm. We used the proceeds at the Abompe farm to finance the<br />

Siiso farm”. She maintained this under cross-examination.<br />

PW5, a nephew of both the plaintiff and the late Kwaku Poku was also clear both<br />

in examination-in-chief and cross-examination that the late Kwaku Poku owned<br />

the Abompe farm. At p.73 between lines 39-40 he said “When I was operating<br />

the store, I used to render accounts to my uncle Kwaku Poku anytime<br />

he came from his farm. The store was sold for £400. My uncle Kwaku Poku<br />

said the 2 nd plaintiff had instructed him to use the proceeds from the sale of the<br />

store to build a house on his (2 nd plaintiff) plot and use the rest to finance his<br />

(Kwaku’s farm). That farm is at Abompe”<br />

At p.74, between lines 23-27, still under examination in chief he continued thus:<br />

“Yes I have been to the Abompe farm. I was even living there with my uncle<br />

Kwaku Poku. I was assisting him to plant the cocoa trees. My grandmother<br />

Yaa Mensah also went to Abompe. Apart from me and my grandmother nobody<br />

else went to Abompe to assist my uncle.”<br />

More clearly under cross examination at p.76 between lines 39-47 he said “Q:<br />

When did Kwaku Poku start cultivation of the Abompe Cocoa farm.<br />

A: In about 1949<br />

Q: At what point in time did you go to assist him.<br />

A: I was then a student so I used to go and assist him during the holidays.<br />

Q: So he started cultivating the Abompe Cocoa farm before 2 nd plaintiff<br />

travelled abroad.<br />

A: Yes”<br />

7

PW1 admitted under cross-examination that PW5 used to come to them at<br />

Abompe during holidays. PW2’s evidence is clearly confused. Granting that PW5<br />

assisted in the Abompe farm in the manner claimed by him, such casual filial<br />

vacation assistance cannot count as any serious contribution towards the family<br />

character of that farm. There is no other affirmative and meaningful assistance<br />

from any other person other than PW1, the deceased’s ex-wife. As to the alleged<br />

financial assistance by the plaintiff towards the acquisition of that farm, the least<br />

said of it the better. In one breath all the proceeds of the plaintiff’s beer bar and<br />

provisions store were to be used to construct the disputed house.<br />

In another breath it was £100 of those proceeds that was to assist in the<br />

cultivation of that form. Yet in another breath it was simply the residue of those<br />

proceeds that was to so assist. In any event one wonders how there could be<br />

spare money from a house that was without electricity, water and a fence wall,<br />

to be spent on a farm.<br />

The clearest pointer of the evidence is that at least the principal or founding farm<br />

at Abompe long predated the proceeds of the sale of plaintiff’s business.<br />

It is however felt that the plaintiff and PW5 stand to gain from the disputed<br />

properties and so their evidence is not disinterested. But so also do the<br />

defendants under the Intestate Succession Law, PNDCL 111, 1985, though the<br />

latter have the benefit of the rule of caution about claims against the estate of a<br />

deceased person, on their side.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

For all the foregoing reasons including the rule about caution regarding claims<br />

against the estates of deceased’s persons it is quite clear that the concurrent<br />

findings of the two courts below suffered, in the respects indicated, from<br />

material misdirections and inadequate considerations as to the law and the<br />

evidence.<br />

Such circumstances warrant the reversal or variation of such concurrent findings.<br />

See Adu v Akamah (2007-2008), SCGLR 143, In re Fianko Akotuah (Dec’d)<br />

Fianko v Djan (2007-2008), SCGLR 165.<br />

Accordingly I will allow the appeal.<br />

8

ANSAH, JSC:<br />

W. A. ATUGUBA<br />

(JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT)<br />

This is an appeal from the judgment of the Court of Appeal dated 17 May 2005<br />

which dismissed an appeal brought before it from the judgment of the High<br />

Court, Kumasi, where the plaintiffs sued for certain reliefs.<br />

The facts and issues in dispute as well as the respective cases of the parties<br />

have been stated so accurately in the opinions read my brother Atuguba JSC that<br />

I have anything to add to them, lest I create unnecessary boredom. I agree with<br />

them and adopt them as my own.<br />

I only wish to add a few words of my own to the opinion just read.<br />

The respective cases for the parties adumbrated in their pleadings, evidence and<br />

submissions, have been stated with equal accuracy.<br />

The plaintiffs are the uterine sister and brother respectively of the late Kwaku<br />

Poku who died intestate on 21 st July 1996; the 2 nd plaintiff was his customary<br />

successor, whilst the defendants are his personal representatives, the first being<br />

his widow and the second, his son.<br />

The pleadings concerning the acquisition of the land in dispute by the parties<br />

have also been referred to by my esteemed brethren. I will not repeat them<br />

here.<br />

The trial judge entered judgment for the plaintiffs on their claims as endorsed<br />

on the writ of summons and on the strength of the evidence before him. The<br />

defendants felt aggrieved by the judgment and appealed against it, first to the<br />

Court of Appeal which affirmed the decision of the trial Court and further to this<br />

court, on the grounds that:<br />

1) “The Court of Appeal in its leading judgment erred in law when<br />

it’s (sic) accepted as facts that the subsequent plot acquired by<br />

Opanin Kwaku Poku was replacement of the plot acquired earlier<br />

by the 2 nd Plaintiffs.<br />

9

2) The Court of Appeal again erred in not giving adequate<br />

consideration to the inconsistencies of the evidence given by the<br />

Plaintiffs/Respondent as to the acquisition of the properties.<br />

3) The Court of Appeal erred in not bringing the issue of capacity<br />

witness’s exception of Kwan v Nyenia (sic) principle.<br />

4) The Court of Appeal erred in holding that the 2nd Plaintiff could<br />

sue in respect of thee properties as customary successor to the<br />

late Kwaku Poku (sic) when he was claiming same as family<br />

properties, as a responsibility that, in the actual head of family of<br />

the family of the plaintiff/Respondent.”<br />

It is obvious this was a typical dispute between a family on one hand and the<br />

survivors of a deceased family member and his immediate family on the other,<br />

over title to a house and other properties. This being an action for the<br />

declaration of title to land and recovery of possession the issue is what must a<br />

plaintiff do in order to succeed?<br />

Section 10, 11 and 12 of the Evidence Decree, 1973, (NRCD 323), come in handy<br />

in answering this question. Section 10 provided that:<br />

1) “For the purposes of this Decree, the burden of persuasion<br />

means the<br />

obligation of a party to establish a requisite degree of belief<br />

concerning a fact in the mind of the tribunal of fact or the<br />

court.<br />

2) The burden of persuasion may require a party<br />

(a) to raise a reasonable doubt concerning the existence or<br />

non-<br />

existence of a fact, or<br />

(b) to establish the existence or non-existence of a fact by<br />

a<br />

preponderance of the probabilities or by proof beyond a<br />

reasonable doubt, or that he establish the existence or<br />

non-existence of a fact by preponderance of the<br />

probabilities, or beyond a reasonable doubt.”<br />

Section 11 on the definition of the burden of producing evidence provided in the<br />

relevant portions that:<br />

X X X X X X X X<br />

10

(4) In other circumstances the burden of producing evidence requires a<br />

party to<br />

produce sufficient evidence which on the totality of the evidence, leads<br />

a reasonable mind to conclude that the existence of the fact was more<br />

probable than its non-existence.<br />

Section 12 of the Decree also defined proof by a preponderance of the<br />

probabilities as:<br />

(1) “Except as otherwise provided by law, the burden of<br />

persuasion requires<br />

proof by a preponderance of the probabilities.”<br />

(2) “Preponderance of the probabilities” means that degree of<br />

certainty of<br />

belief in the mind of the tribunal of fact or the Court by which<br />

it is convinced that the existence of a fact is more probable<br />

than its non-existence.”<br />

Brobbey JA (as he then was) wrote in explanation of these provisions of the<br />

Decree in Yorkwa v Duah [1992-93] GBR 278, at 282 that:<br />

“Part II of NRCD 323 which deals with the burden of proof covers on one<br />

hand the burden of producing evidence under sections 11, 12 and 13.<br />

Considering the wording of section 10(1) in the light of the Commentary on the<br />

Evidence Decree…I am of the view that the expression burden of persuasion<br />

should be interpreted to mean the quality, quantum, amount, degree or extent<br />

of evidence the litigant is obligated to adduce in order to satisfy the requirement<br />

of proving a situation or a fact. The burden of persuation differs from the burden<br />

of producing evidence.<br />

Under sections 11, 12 and 13, particularly section 179(1) of the Decree,<br />

the burden of producing evidence means the duty or obligation lying on a litigant<br />

to lead evidence. In other words, these latter sections cover which of the<br />

litigating parties should be the first to lead evidence before the other’s evidence<br />

is led.<br />

… Therefore it is the plaintiff who will lose first, who has the duty or<br />

obligation to lead evidence in order to forestall a ruling being made against him.<br />

This is clearly amplified in section 11(1) of NRCD 323 which provides that:<br />

‘“For purposes of this Decree, the burden of producing<br />

evidence means the obligation of a party to introduce<br />

sufficient evidence to avoid a ruling against him on the<br />

issue.”’<br />

11

The learned justice went further to explain that:<br />

“The Evidence Decree makes provision for the duty or obligation to adduce<br />

evidence to shift from one party to the other. In a situation …the duty or<br />

obligation could shift from the plaintiff to the defendant. If and when it is shifted,<br />

the defendant would be required to lead evidence to establish the sale once he<br />

claimed to have had possession by reason of sale of the house to him. When the<br />

duty or obligation to adduce evidence shifts, and the defendant fails to adduce<br />

evidence or any evidence on the sale, the ruling of the court on the sale will be<br />

against the defendant. This is the reason for the provision in section 14 which<br />

says that:<br />

“Except as otherwise provided by law, unless and until it is shifted a<br />

party has the burden of persuasion as to each fact the existence or<br />

non-existence of which is essential to the claim or defence he is<br />

asserting.’”<br />

Applying these legal provisions, explained in such details by the learned Judge to<br />

the facts of this appeal, it becomes clear that the respective positions have been<br />

that whereas the plaintiffs asserted title to the properties in dispute to have<br />

belonged to the family, the defendants laid it in the late Kwaku Poku as his selfacquired<br />

properties. Section 11(4) of the Decree put the obligation in civil<br />

proceedings like the present, of producing evidence on a party to produce<br />

sufficient evidence so that on all the evidence, a reasonable mind could conclude<br />

that the existence of the fact was more probable than its non-existence. It was<br />

all a question of which of the parties was better able to prove its case than the<br />

other on all the evidence led at the trial?<br />

In Odoi v Hammond [1971]2 GLR 375, CA, Azu Crabbe JA, (as he then<br />

was), said at p 382 that:<br />

“it is now common learning in this country that in an action<br />

for declaration of title to land the onus is heavily on the<br />

plaintiff to prove his case, and he cannot rely on the weakness<br />

of to the defendant’s case. He must indeed ‘show clear title’:<br />

per Yates Ag C.J. in Kuma v Kuma 1934 2 WACA 178 at p 179.<br />

In Kponuglo v Kodadja 1933 2 WACA 24 at p. 25, the <strong>Judicial</strong><br />

Committee of the Privy Council observed that in an action for<br />

a declaration of title the “first question logically and<br />

chronologically, to consider in the appeal is the traditional<br />

evidence regarding the acquisition of a title to the disputed<br />

territory.” For a stool or family to succeed in an action for a<br />

declaration of title it must prove its method of acquisition<br />

12

conclusively, either by traditional evidence, or by overt acts of<br />

ownership exercised in respect of the land in dispute.”<br />

As stated the plaintiffs led evidence to discharge of the onus that lay on them.///<br />

as outlined above in this opinion. There was evidence from the PW1 Afua Manu<br />

the widow of the late Kwaku Manu that the original plot was eaten up or<br />

swallowed by the newly constructed road, PW5 operated the provisions store<br />

that was sold for #400.00 by Kwaku Poku out of which #300 was used for the<br />

building and #300 for developing the Abompe farm; PW2, Kofi Adu, supported<br />

the claim that Kwaku Poku cultivated the Abompe farm; PW3, Charles Kusi and<br />

the PW4 Amma Ode, corroborated the plaintiff’s evidence that the second<br />

plaintiff’s sister, the deceased 1 st plaintiff contributed to the acquisition of the<br />

house, which consisted of providing electricity power and other utilities to the<br />

building, and also cement blocks for a fence wall around the building.<br />

The plaintiffs having led that kind of evidence in favor of the family as owners of<br />

the disputed properties, the onus shifted to the defendants who laid ownership<br />

in the properties in Kwaku Poku, to lead that kind of evidence that would tilt the<br />

balance of the probabilities in their favor.<br />

The defendants accepted the gauntlet and led evidence by the DW1 Dauda Ali a<br />

caretaker for Kwaku Poku’s cocoa farm at Siiso and a house in the Stadium area<br />

in Kumasi. It is common knowledge that that is not the same as New Amakom<br />

where the disputed house is situated. The DW2 Isaac Asare Lartey said he was<br />

a tenant and the first defendant his landlady as per the tenancy agreement in<br />

Exhibit D.<br />

In this appeal, the learned trial judge properly directed himself in resolving the<br />

dispute before him by referring to the principle in Kodilinye v Odu (2 WACA),<br />

explained in Ricketts v Addo [1975] 2 GLR, before coming to his judgment.<br />

It is trite that an appeal to this court is by way of a rehearing and this court will<br />

consider the evidence led at the trial to see whether or not it supported the<br />

judgment of the lower courts, and the submissions before it in support of or<br />

against the appeal. I must observe from the record that the 1 st plaintiff died in<br />

the course of the trial but was never substituted, thus leaving the second as the<br />

lone crusader.<br />

In support of ground one of appeal, the appellant submitted that the Court of<br />

Appeal confirmed the findings of the trial judge relying on the evidence adduced<br />

at the trial by the second plaintiff, supported as it were by the PW1, Afua Manu<br />

the widow of Kwaku Poku and the PW5, Yaw Agyei his nephew. The Court of<br />

Appeal considered the evidence as corroborating each other; for example, the<br />

13

evidence of the second plaintiff was that the construction of the house started<br />

before the second plaintiff left the shores of Ghana for the United Kingdom (UK),<br />

whereas the evidence on the record showed that it took place whilst he was in<br />

the UK. The trial judge found as a fact that Kwaku Poku built the house in<br />

dispute.<br />

The implication was that the house was under construction before the second<br />

plaintiff left for the UK, for there was evidence that the plot acquired by the<br />

second plaintiff was eaten up by the construction of the Kumasi-Accra road;<br />

whilst the second plaintiff was in the U.K; there was no development on the land<br />

for if there had been any that would have been eaten up as well by the said<br />

construction. But the evidence was that whilst the second plaintiff was in Ghana,<br />

the construction had not even started. That was why he only asked Kwaku Poku<br />

to take a replacement plot and not a replacement house. If his evidence were to<br />

be true, that would have been also eaten up during the construction of the road.<br />

In another consideration, the evidence of the second plaintiff/ respondent was<br />

not too creditworthy. Why did he ask Kwaku Manu to take the replacement plot<br />

in his Manu’s name but not his if he was truly the owner of the lost plot?<br />

On the acquisition of the house and the cocoa farms, the trial judge found that<br />

proceeds from the Abompe farms were used to acquire the Siiso farms and the<br />

house in dispute; and also that the family contributed substantially towards the<br />

acquisition. Besides this, the second plaintiff asserted in his evidence that<br />

proceeds from his store and stock-in-trade was used for the same purpose.<br />

This finding has been severely criticized by the appellants. To their counsel, the<br />

evidence by the plaintiffs was inconsistent with each other on fundamental issues<br />

before the court, like the acquisition of the disputed properties and so the<br />

plaintiff’s claims should have been dismissed. I shall come back to this aspect of<br />

submissions by the appellant.<br />

The admitted fundamental issues are issues of fact, and the law is settled that all<br />

issues of facts are for the trial judge to determine. Counsel cited Doku v Doku &<br />

Another [1992-93] GBR 367, CA, and Bisi v Tabiri alias Asare [1987-88] 1 GLR<br />

360, to buttress his point. The facts in Doku v Doku (supra) were that each party<br />

claimed sole ownership of the property in dispute, but at the end of the trial, the<br />

trial judge made definite findings of facts and upheld the claim by the 2nd<br />

defendant on his counterclaim for a declaration of title. The plaintiff appealed<br />

against the judgment on several grounds a summary of which was that the<br />

judgment was against the weight of evidence on record. Dismissing the appeal,<br />

the Court of Appeal stated the settled principles governing appeals on such<br />

grounds to be that:<br />

14

“The generally accepted principle of law is that findings of<br />

fact made by a trial judge should not be disturbed unless they<br />

are perverse or not supported by the evidence on record. In<br />

Bruce v Attorney General [1967] GLR 170, it was held, inter<br />

alia, that an appellate court should not disturb findings of<br />

fact made by a trial judge, but it was equally true that an<br />

appellate court was not precluded from doing so.”<br />

These principles of law were correctly stated by the Court of Appeal and ought to<br />

be affirmed.<br />

In Bisi v Tabiri alias Asare [1987-88] GLR 360, this court reiterated this principle<br />

when it held that:<br />

“I cannot believe that it was ever intended that the Court of<br />

Appeal (or any other appellate court for that matter) should<br />

move into a new era of regular questioning of decisions of<br />

trial judges on issues of fact, as distinct from law, which are<br />

supportable. For this reason there could be no ground for<br />

caviling at the judge’s exercise of discretion or duty in the<br />

selection of witnesses to believe or in stating his findings of<br />

fact.”<br />

In stating his the SC did not make any reference whatsoever to what was stated<br />

in Bruce v Attorney General.<br />

On the sore question whether Kwaku Poku acquired the plot of land on which the<br />

Amakom house stood by himself, the trial judge minced no words when he found<br />

as a fact that it was given as a replacement to the plot that had been given out<br />

to him previously but was eaten up as a result of the construction of the Kumasi-<br />

Accra road. I think the judge had enough evidence to make his finding and for<br />

that reason was not so perverse as to be reversed on appeal. The question was<br />

where was the evidence led to corroborate this claim of replacement plot? The<br />

second plaintiff said in his evidence in chief that he obtained an allocation paper<br />

from the Amakom stool, but he did not tender it in evidence saying he left it with<br />

Kwaku Poku. Dead men do not speak. The second plaintiff also made a startling<br />

statement in his evidence in chief that there were no title deeds to the house. He<br />

was literate who knew the importance of such documents; he would have taken<br />

them from Poku if he truly owned or even built the house. He could have<br />

changed all names on all documents on the house into either his or the family as<br />

he said he had wanted to have built the house for. He did not and left a huge<br />

credibility gap in his evidence concerning the ownership of the house. I therefore<br />

have some disquiet about how the Court of Appeal affirmed the findings of<br />

ownership of the house by the trial court.<br />

15

It must be borne in mind in this appeal that the Court of Appeal unanimously<br />

affirmed the judgment of the trial court on all facts and concurred in its<br />

judgment. An appeal from such a judgment is governed by the principle stated in<br />

Koglex No 2 v Field [2000] SCGLR 175 that:<br />

“(2) Where the first appellate court had confirmed the<br />

findings of the trial court, the second appellate court would<br />

not interfere with the concurrent findings unless it was<br />

established with absolute clearness that some blunder or<br />

error resulting in a miscarriage of justice, was apparent in<br />

the way in which the lower court had dealt with the facts.”<br />

Authorities on this principle abound in our books and Achoro v<br />

Akanfela [1996-97] SCGLR 209, Obresiwa II v Otu [1996-97] 628 are<br />

cited for further elucidation and support.<br />

A second appellate court would justifiably reverse the judgment of a first<br />

appellate court where the trial committed a fundamental error in its findings of<br />

fact but the first appellate court did not detect the error but affirmed it and<br />

thereby perpetuated the error. In that situation it becomes clear that a<br />

miscarriage of justice had occurred and a second appellate court will justifiably<br />

reverse the judgment of the first appellate court.<br />

Thus stated, it cannot be said an appellate court cannot set aside a judgment<br />

where two lower courts had made concurrent findings of facts.<br />

An appeal this court is by way of a rehearing meaning this court is entitled to<br />

review the evidence on the record to ascertain whether there is enough<br />

satisfactory evidence in support of both the findings and conclusion which was<br />

supported by the Court of Appeal since an appeal is by way of a rehearing of the<br />

case: see Wangara Gyato v Gyato Wangara [1982-83] GLR 639, holding 1;<br />

Akufo-Addo v Cathline [1992] GLR 377, holding 3; Fijal Stool v Effia Stool…<br />

In the present appeal the appellant assayed to demonstrate why the judgment of<br />

the Court of Appeal ought to be reversed by submitting before us that there<br />

were inconsistencies, and contradictions in the evidence proffered by the<br />

plaintiffs in support of their case.<br />

The above submissions deserve some analysis. In Effisah v Ansah [2005-2006]<br />

SCGLR 943, one of the issues in the appeal was the submission by the appellant<br />

that there were inconsistencies and contradictions in the evidence of the plaintiff.<br />

This court had no difficulty in dismissing the appellant’s complaint and said, in<br />

stating the law, in the opinion delivered by Mrs. Georgina Wood JSC (as she then<br />

was, but now CJ) that:<br />

“In the real world evidence led at any trial which turns<br />

principally on issues of fact and involving fair number of<br />

16

witnesses, would not be entirely free form inconsistencies,<br />

conflicts or contradictions and the like. In evaluating<br />

evidence led at a trial, the presence of such matters per se<br />

should not justify a wholesale rejection of the evidence to<br />

which they may relate. Thus, in any given case, minor,<br />

immaterial insignificant or non-critical inconsistencies must<br />

not be dwelt upon to deny justice to a party who has<br />

substantially discharged his or her burden of persuasion.”<br />

The learned Chief Justice then went on to give a proper direction which I find<br />

very useful in guiding a court in the face of such criticisms in a judgment as a<br />

ground of appeal, at page 960 of the judgment that:<br />

“Where inconsistencies or conflicts in the evidence are<br />

clearly reconcilable and there is a critical mass of evidence<br />

on crucial or vital matters, the court would be right to gloss<br />

over these inconsistencies.”<br />

In this appeal, the Court of Appeal observed that the events about which the<br />

witnesses testified took place over 40 years earlier and in circumstances as these<br />

there were bound to be inconsistencies in the narratives without any intention to<br />

tell a lie, as explained in Adjeibi Kojo v Bonsie….<br />

I have examined the so called inconsistencies and found the criticism to have<br />

been well founded. They were not inconsistencies at all, or even if they were<br />

any, they were not so monumental or irreconcilable that the evidence must be<br />

rejected. At the highest, the most important part of the evidence was that the<br />

house was built by Kwaku Poku and whether it was before or after the second<br />

respondent journeyed to Europe was of a little or no significance. At any rate this<br />

was an issue of fact entirely within the province of the trial judge to determine<br />

one way or the other. Provided he resolved the issue in favor of or against one<br />

side based on the evidence before him, the settled law is that an appellate court<br />

would be slow to interfere with or set aside the finding of fact so made. ///And<br />

that corroborative evidence was not lacking for it was provided by the PW1, Afua<br />

Manu, the widow of Kwaku Poku and the PW5, Yaw Agyei, his nephew. The trial<br />

judge not only had the benefit of hearing these witnesses in their viva voce<br />

evidence in court, he also saw their demeanor as they did so. He came to the<br />

conclusion that their evidence was credible and worthy of belief. The veracity or<br />

otherwise of a witness is a function reserved exclusively for the trial judge and<br />

will ordinarily not be interfered with except it was proved he did not take<br />

advantage of seeing the witnesses as they testified before him, or drew the<br />

wrong inferences from the evidence. That appears to have been the case here.<br />

17

From the nature of the facts and issues before the court, all the evidence must<br />

be considered dispassionately. The appellants relied heavily on the fact that<br />

documents on the house like building plans and permits, demand notices and<br />

receipts for payments of rents were in the name of Kwaku Poku but though in<br />

law that, per se, was no proof of title to a property in dispute, they are not be<br />

glossed over for they serve as strong acts of ownership which may be spokes in<br />

a claim for declaration of title by a plaintiff.<br />

I am bold to say that in the face of the strong challenge by the defendants on<br />

the title to the house in dispute, it was not enough for the plaintiffs to have<br />

relied on only the viva voce evidence by the plaintiffs no matter who how many<br />

they are. Corroborative evidence that was likely to exist were their evidence to<br />

be believed as true; official documents from official or public sources could have<br />

been produced, see Majolagbe v Larbi [1959] GLR…But in this case nothing like<br />

that came from the plaintiffs.<br />

The respondent led no sufficient evidence to show how the second plaintiff<br />

acquired the plot of land on which the house stood. The evidence in the<br />

documents in his name must be matched against the totality of the evidence on<br />

record that even if Kwaku Poku built the house, the family made contributions,<br />

substantial or otherwise, towards the acquisition, for the store run by the PW5<br />

and the stock in trade were sold and the proceeds or part thereof were pooled<br />

together for the acquisition, proceeds from the farm at Siiso was utilized in<br />

acquiring the Abompe farm.In circumstances like this the legal conclusion was<br />

that the house at New Amakom Extension, Plot Number 11, Block 24, so<br />

acquired are stamped with the family character, or badge was against the weight<br />

of the evidence . The case that they were acquired by the second plaintiff was<br />

not supported by the evidence on record as found by the trial court. The appeal<br />

by the respondent must fail.<br />

The sum total of grounds one and two of appeal was that the judgment of the<br />

trial court was against the weight of evidence. It requires no authority to be cited<br />

in support of the proposition that an appeal to this court is by way of a rehearing<br />

and even though it is not the function of the appellate court to assess<br />

the veracity, truthfulness or otherwise of the witnesses in a civil case, it is<br />

incumbent on the court to take into account the testimonies and all the evidence,<br />

documentary or oral, adduced at the trial before arriving at its decision so as to<br />

satisfy itself that, on a preponderance of the probabilities, the conclusions of the<br />

trial judge are reasonably or amply supported by the evidence: see Tuakwa v<br />

Bosom [2001-2002] SCGLR 61.<br />

Accordingly the Court of Appeal erred in affirming the findings of fact by the trial<br />

court and grounds 1 and 2 of Appeal are both allowed.<br />

18

Grounds 3 and 4 of appeal touching and dealing with the plaintiffs’ capacity to<br />

sue raise important issues of law and will be considered together.<br />

These grounds of appeal were that:<br />

3. “The Court of Appeal erred in not bringing the issue of<br />

capacity within the reception (sic) of Kwan v Nyieni principle<br />

and the Court of Appeal erred in holding that the 2 nd plaintiff<br />

could sue in respect of these properties as customary<br />

successor to the late Kwaku Poku when he was claiming<br />

properties a responsibility that, in the prerogative of the<br />

actual Head of family of the Plaintiff/Respondent.<br />

4. The issue of capacity is fundamental to our law and being<br />

a question of law can be raised at anytime even on appeal.<br />

The Court therefore erred in holding that the<br />

Defendants/Appellants did not raise that issue at the trial<br />

court and therefore could not do so at the Appellate Court.”<br />

The material holding in Kwan v Nyieni [1959] GLR 67 was:<br />

“as a general rule the head of family, as representative of the family<br />

is the proper person to institute suits for the recovery of family land;<br />

(1) to this general rule there are exceptions in certain special<br />

circumstances, such as:<br />

(i).where the family property is in danger of being lost to the<br />

family, and it is shown that the head either out of personal<br />

interest will not make a move to save or preserve it;<br />

(ii). where owing to a division in the family, the head and<br />

some of the principal members will not take any step;<br />

Or<br />

iii. where the head and the principal members are deliberately<br />

disposing of the family property in their interest, to the<br />

detriment of the family as a whole.<br />

In any such special circumstances, the Court will entertain<br />

an action by any member of the family, either upon proof<br />

that he has been authorized by other members of the family<br />

to sue, or upon proof of necessity, provided that the Court is<br />

19

satisfied that the action is instituted in order to preserve the<br />

family character of the property.”<br />

The grounds of appeal quoted above sum up much of the dispute in this appeal.<br />

There is no paucity or dearth of authority on this point. Nyamekye v Ansah<br />

[1989-90] 2GLR 152 CA considered who qualifies to be head of family and made<br />

it clear at page 162 of the report, that when a successor is appointed by the<br />

family he/she automatically becomes the head of family; he can also be<br />

appointed by popular acclamation or by virtue of the fact that he/she is the<br />

oldest member of the family. Again, any person who the family permits to deal<br />

with family property for and on behalf of the family, or to exercise the functions<br />

of a head of family, is deemed to be the head of family until the contrary is<br />

proved: see Mills v Addy (1958) 3 WALR 357, and also Sarbah’s Fanti Customary<br />

Laws (1897 ed).<br />

In Nyame v Ansah (supra), the Court of Appeal held further that:<br />

“As a general rule, the head of family as representative of the family is the<br />

proper person to institute suits for the recovery of family land: see Kwan v Nyieni<br />

[1959] GLR 67 at 72, CA. And where the authority of a person to sue in<br />

representative capacity is challenged, the onus is on him to [prove] that he has<br />

been duly authorized. He cannot succeed on the merits without first satisfying<br />

the court on that important preliminary issue.<br />

The plaintiffs/appellants sued as the “customary successor of the late<br />

Kwaku Poku for themselves and on behalf of the family of the late<br />

Kwaku Poku” for reliefs itemized above. They sought declarations that the<br />

properties were for the family, pleaded facts and led evidence in support. In<br />

those circumstances the exception in the proviso to the principle in Kwan v<br />

Nyieni (supra), does apply as respondents acted to claim and protect the family<br />

character of the properties in dispute.<br />

At the application for directions the parties settled, inter alia, the following issues<br />

for trial:<br />

“3 Whether or not the purchase price of the Beer Bar and provisions<br />

Shop was given to the late Kwaku Poku to put up house on Plot 11,<br />

Block 24, New Amakom, for the family.<br />

5 Whether or not the house in dispute is family property.<br />

8 Whether H/No. Plot 11, Block 24, New Amakom extension is family<br />

property.<br />

9 Whether or not the Abompe and Siiso cocoa farms are family<br />

properties.<br />

20

12 Whether or not the plaintiffs are entitled to the reliefs being<br />

sought by them.”<br />

Thus, whether the plaintiffs had the requisite capacity to sue was made an issue<br />

for trial. That issue was raised by virtue of the general traverse in the statement<br />

of defense.<br />

It is unfortunate the trial judge did not consider the issue of capacity anywhere<br />

in his entire judgment. When he considered whether or not the properties in<br />

dispute were for the family he should have gone forward to also consider if they<br />

were family properties then whether or not the plaintiffs were clothed with the<br />

requisite capacity to sue in respect thereof. That was irrespective of whether or<br />

not the parties made that an issue for trial. Capacity to sue was a matter of law<br />

and could be raised at any stage of the proceedings even on appeal. It can be<br />

raised by the court suo motu.<br />

It was the Court of Appeal which raised the issue and resolved it by holding that<br />

the plaintiffs pleaded in paragraph 4 of their statement of claim that the second<br />

plaintiff was “the customary successor of the late Kwaku Poku.” The respondents<br />

admitted the averment in the said paragraph 4 and with that there was no need<br />

to prove the fact any further. Akamba JA, concurring with the opinion of Anin<br />

Yeboah J.A (as he then was, who read the leading judgment), said that in Akan<br />

customary law, a person appointed a customary successor to a deceased in the<br />

family becomes the head of the immediate family and is the proper person to<br />

sue and be sued in respect of that particular family<br />

Property. The Court relied on Atta v Amissah (1970) CC 73, that:<br />

“The person appointed successor to the deceased becomes,<br />

under customary law, the head of the immediate family, and<br />

is as such head, the proper person to sue and be sued in<br />

respect of that particular family property.” N.A. Ollennu’s<br />

invaluable Customary Land Law in Ghana made the same point at<br />

page 151.<br />

In Sarkodie I v Boateng II [1982-83] GLR 715, SC, this court said that<br />

“It was elementary that a plaintiff or petitioner whose capacity was<br />

put in issue must establish it by cogent evidence. And it was no<br />

answer for a party whose capacity to initiate proceedings has been<br />

challenged by his adversary to plead that he should be given a<br />

hearing on the merits because he had a cast-iron case against his<br />

proponent.”(es)<br />

The Supreme Court considers the question of capacity in initiating proceedings as<br />

very important and fundamental and can have a catastrophic effect on the<br />

fortunes of a case. Thus, in Republic v High Court, Accra, Ex parte Aryeetey<br />

(Ankra Interested Party, [2003-2004] SCGLR 398, the brief facts were that the<br />

21

interested party knew that his father had died testate and the will had been<br />

read, though probate had not been taken, he failed to disclose to the court that<br />

he was one of the executors of the said will, and that probate had not been<br />

taken. In suing, therefore as a beneficiary and customary successor, of his late<br />

father the interested party lacked the capacity to sue, rendering the writ and<br />

subsequent proceedings thereon null and void.<br />

The Court held that:<br />

“Any challenge to capacity therefore puts the validity of a writ in<br />

issue. It is a proposition familiar to all lawyers that the question of<br />

capacity, like the plea of limitation, is not concerned with the merits<br />

so that if the axe falls, then a defendant who is lucky enough to<br />

have the advantage of the unimpeachable defence of lack of capacity<br />

in his opponent, is entitled to insist upon his rights: see Akrong v<br />

Bulley [1965] GLR 469 SC.”<br />

It must be pointed out that in the present appeal, there was no issue raised on<br />

the position of the plaintiff as a head of family for that was admitted on the<br />

pleadings.<br />

Thus, it became clear that the Court of Appeal did consider all the issues at stake<br />

including the capacity of the plaintiff to sue, took into consideration all the<br />

relevant authorities governing the issue before concluding that any attempt by<br />

the appellants at this stage to question the Respondent’s capacity after the initial<br />

admission thereof, is unfounded, uncalled for and a mere waste of time and<br />

effort.<br />

In my opinion, the Court of Appeal did err on grounds 1 and 2 of the appeal, as<br />

the findings by the trial court were not supported by the evidence on record, and<br />

the conclusion was not proper. The Court of Appeal disabled itself from coming<br />

to the proper conclusion in affirming the decision of the trial court.<br />

With that I am persuaded that the appeal ought to succeed and is<br />

consequently allowed.<br />

I may remark now that in United Products Ltd. v Afari (1929) D.C. ’29-’31<br />

at p11, Deane CJ held that:<br />

“the (frequently adopted) presumption with regard to land in<br />

this country is that it is family land.” Lingley J made the same point in<br />

Andoh & Anor. v Franklin & Ors. D,C.(Land) 52-55; see also Codjoe v Kwatchey<br />

1935 (2) WACA 371, and more recently, Nti v Amina [1984-86] 2 GLR 135 at<br />

146-147, C.A. With the passage of time the presumption reduced in strength<br />

and became rebuttable. By 1935, it had become not too strong a presumption as<br />

it used to be in time past, so however that in 1960 the then Court of Appeal<br />

summed up the situation in Larbi v Cato [1960] GLR 146 that:<br />

22

“Whilst it is true that customary law requires that the presumption in favor<br />

of family property should be rebutted by evidence and that the onus is on<br />

who asserts sole ownership, that onus shifts once it is shown that that<br />

person has been dealing with the property as his own….”<br />

In 1986, the Court of Appeal held at p 147 that: “in modern Ghana the said<br />

presumption should not be a strong one and the burden of proof on the one who<br />

asserts sole ownership should be very light and that any slight but reliable<br />

evidence should be sufficient to rebut that presumption.” see Nti v Amina (supra)<br />

The defendants in this appeal bore the onus of rebutting the presumption in<br />

favour of the plaintiffs even though it may be weak now.<br />

Now, it is common knowledge that statute has given more recognition to the<br />

ownership of property by the individual than the family. See The Intestate<br />

Succession Law, 1986, PNDCL 111. In this appeal, the defendant who assumed<br />

the burden of proving on the preponderance of the probabilities that the<br />

properties were for the estate of Kwaku Poku and not the family, was able to<br />

rebut the presumption with evidence that was more than slight and reliable.<br />

Now, the old order has changed giving way to the new. The lower courts did not<br />

pay proper regard to the law applicable to the facts of this case, and came to the<br />

wrong conclusions and gave judgment in favor of the plaintiffs on their claims.<br />

This is a proper case to interfere with and to set aside the concurrent judgments<br />

of the lower courts.<br />

The judgment of the Court of Appeal is hereby set aside and the appeal allowed.<br />

ADINYIRA (MRS), JSC:<br />

J. ANSAH<br />

(JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT)<br />

I have had the privilege of reading the judgments of my brothers Ansah JSC and<br />

Dotse JSC, and I agree that the appeal be allowed. After a careful scrutiny of the<br />

record, I find it very difficult to accept the concurrent decisions of the trial and<br />

appellate court that the properties in dispute were family properties. The<br />

23

principles governing appeals against concurrent findings of fact by two lower<br />

courts is well grounded and expounded in the case cited by my brother Dotse,<br />

ACHORO & Anr v. Akanfela & Anr [1996-97] SCGL 209. In support I wish to add<br />

the cases of Kpoglex Ltd. No. 2 v. Field [2000] SCGLR 175 and the more recent<br />

case of Adu v. Ahamah [2007 -2008] SCGLR 143. Boateng (No.2) v. Manu (No.2)<br />

[2007-2008] SCGLR 1117. Social Security Bank Ltd. V. CBAM Services Inc. [2007-<br />

2008] SCGLR 894. Applying the principle to this case I agree that there was<br />

overwhelming evidence both documentary and overt acts of ownership by<br />

Opanin Kwaku Poku which if the Court of Appeal had properly appreciated and<br />

evaluated, they would have come to a different conclusion from the trial court.<br />

Had the lower courts applied the rule of evidence of presumption of title raised<br />

by acts of ownership under section 48 (2) of the Evidence Decree, 1975 NRCD<br />

323 their conclusion would have been different.<br />

I wish to cite one example of overt acts of ownership, to add to what my brother<br />

Dotse enumerated in his well written opinion. The 2 nd Plaintiff who claimed he<br />

bought the land and provided money to put up the house in dispute was ejected<br />

from this same house by the late Opanin Kwaku Poku. Yet during Opanin Kwaku<br />

Poku’s lifetime, the 2 nd plaintiff did not lift a finger to protest nor assert his right<br />

even if not as the owner but as a member of a family that is alleged to own the<br />

house. Clearly the 2 nd Plaintiff’s conduct exposes the hollowness of his claim<br />

against the widow and children of Opanin Kwaku Poku. The preponderance of<br />

the evidence weighs heavily against the findings of the courts below and<br />

accordingly this Court ought to interfere and reverse the finding of the lower<br />

courts. The appeal accordingly succeeds.<br />

S. O. A. ADINYIRA (MRS)<br />

(JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT)<br />

24

DOTSE, JSC:<br />

FACTS<br />

The Plaintiffs/Respondents/Respondents, hereinafter referred to as the Plaintiffs<br />

instituted action against the Defendants/Appellants/Appellants, hereinafter<br />

referred to as the Defendants in the High Court, Kumasi claiming reliefs in the<br />

nature of Declarations in respect of three immovable properties as their family<br />

properties, namely;<br />

i. House No. Plot II Block 24 Amakom Kumasi<br />

ii. Cocoa farm situate at Siiso on Kwapong Stool lands and<br />

iii. Farmstead situate at Abompe and Kunso stool lands.<br />

The Defendants did not counterclaim before the trial court.<br />

FACTS OF THE CASE<br />

The Plaintiffs are the sister and brother of one Opanyin KWAKU POKU who died<br />

intestate in Kumasi on the 21 st day of July 1996.<br />

Following his death intestate, the Defendants herein, who are the widow and son<br />

respectively of the said OPANYIN KWAKU POKU successfully applied for and<br />

obtained Letters of Administration in respect of the estate of their deceased<br />

husband and father.<br />

Included in the inventory of the properties listed in the application for the grant<br />

of the letters of Administration are the properties referred to supra. The Plaintiffs<br />

contending that the said properties are family properties, initiated the suit<br />

against the Defendants in the High Court Kumasi.<br />

The Defendants denied the claims by the Plaintiffs and asserted that the<br />

properties in dispute were the self acquired properties of the deceased Opanyin<br />

Kwaku Poku.<br />

25

On 23-09-03, judgment was entered for the Plaintiffs on all their reliefs in the<br />

trial court and aggrieved by that decision the Defendants filed a notice of Appeal<br />

in the Court of Appeal. The Defendants main ground of appeal was that the<br />

judgment was against the weight of the evidence. The Defendants subsequently<br />

argued two additional grounds of appeal namely that the learned trial judge<br />

shifted the burden of proof onto the Defendants and the Plaintiffs lacked the<br />

capacity to institute the action in the first place.<br />

On the 17 th day of May 2005, the Court of Appeal by a unanimous decision<br />

dismissed the appeal on the grounds that the appeal in its entirety lacked any<br />

merits whatsoever.<br />

Further aggrieved by the decision of the Court of Appeal the Defendants<br />

appealed to the Supreme Court by filing a notice of Appeal on the 15 th of July<br />

2005.<br />

GROUNDS OF APPEAL<br />

The grounds of appeal were as follows:<br />

1. The Court of Appeal in its leading judgment erred in law when it accepted<br />

as fact that the subsequent plot acquired by Opanin Kwaku Poku was<br />

replacement of the plot acquired earlier by the 2 nd Plaintiff.<br />

2. The Court of Appeal again erred in not giving adequate consideration to<br />

the inconsistencies of the evidence given by the Plaintiffs/Respondents as<br />

to the acquisition of the properties.<br />

3. The court of Appeal erred in not bringing the issue of capacity within the<br />

reception of Kwan v Nyieni principle.<br />

4. The Court of Appeal erred in holding that the 2 nd Plaintiff could sue in<br />

respect of these properties as customary successor to the late Kwaku<br />

Poku, when he was claiming same as family properties, a responsibility<br />

that is the prerogative of the actual Head of family of the Plaintiff-<br />

Respondent.<br />

At the trial court, both parties testified and called witnesses.<br />

26

Whilst it was the 2 nd Plaintiff who testified for and on behalf of the Plaintiffs, and<br />

called five witnesses, both Defendants testified and also called witnesses.<br />

PLAINTIFFS CASE<br />

What was the evidence led by the Plaintiffs to prove the method of acquisition of<br />

the property in dispute? According to the 2 nd Plaintiff sometime around 1949, he<br />

acquired a piece of land from the Amakomhene on orders from the Asantehene<br />

Prempeh II. In 1952, he traveled to the United Kingdom and whilst there, he was<br />

informed by his mother that the plot of land he had acquired had been affected<br />

by the construction of the Accra-Kumasi highway. According to the Plaintiff, his<br />

mother assured him that she had informed the Otumfuo and the Amakomhene<br />

who promised to give him a replacement plot but his absence from Ghana at the<br />

time was going to pose a problem. He therefore instructed his mother to let his<br />

brother, the late Kwaku Poku to act on his behalf.<br />

He also led evidence that he owned a beer bar and a provision store which he<br />

left in the care of his late brother when he departed for the UK. He later directed<br />

that the bar and the stock in it be sold and the proceeds used to fund the<br />

construction of the house. According to the 2 nd Plaintiff, he came back from<br />

England in 1955 and the Deceased took him round to show him the completed<br />

house. He said the property had not been fenced at the time. He left again for<br />

the UK and came back in 1960 where the house was in the same condition as he<br />

had seen it in 1955 except that a fence wall had now been built around the<br />

house. He said the fence wall had been constructed by the 1 st Plaintiff out of her<br />

own resources. Later in 1974, he visited again and the 1 st Plaintiff informed him<br />

that she had moved into the house and had connected water and electricity to<br />

the House. He tendered in Evidence Exh A, which is a receipt from the Ghana<br />

Water and Sewerage Corporation dated January 1994 and in the name of Akosua<br />

Dufie who until her demise was the 1 st Plaintiff in this matter.<br />

From the record, this was the only evidence tendered by the Plaintiff in support<br />

of his case of proving title to the land. The 2 nd Plaintiff also said in his evidence<br />

that he had been given an “allocation paper” evidencing the acquisition of the<br />

27

property. This the Plaintiff alleges he handed over to his brother before he left<br />

for England after explaining to him what it was.<br />

DEFENDANTS CASE<br />

2 nd Defendant in his evidence stated that the properties in dispute were the self<br />

acquired properties of his late father. In support of this, he tendered in exhibits<br />

1-13. Exhibit 1 was a goldsmith’s license even though it was not in dispute that<br />

the deceased had been a goldsmith before becoming a farmer. Exh 2 entitled<br />

“undertaking” was dated 23 rd June 1958 and attested to by the deceased and an<br />

officer from the Asantehene’s Land office. It was also copied to the<br />

Amakomhene. Also tendered in evidence were copies of site plans and receipts<br />

for the payment of tribute to various stools and property and ground rent all<br />

issued in the name of Kwaku Poku the deceased.<br />

From the grounds of appeal filed by the Defendants in this court, coupled with<br />

the Statement of Case filed by Counsel for the parties, it is clear the thrust of the<br />

appeal revolves around the rival contentions of the Plaintiffs that the properties<br />

in dispute are family properties in contrast to the Defendants claims that that the<br />

properties were the self-acquired properties of the deceased, KWAKU POKU.<br />

From the evidence on record, the resolution of this dispute will revolve around<br />

1. Assessment of the conflicting pieces of evidence adduced by the parties at<br />

the trial court.<br />

2. The source of funding as determined by the learned trial judge at the trial<br />

court and;<br />

3. Since the issue of CAPACITY has been argued, it will be considered first as<br />

a matter of procedure.<br />

SUBMISSIONS ON CAPACITY<br />

The Counsel for the Appellants argued doggedly the issue of capacity of the<br />

Plaintiffs to institute the present action. Counsel advanced the argument that as<br />

the Plaintiffs were claiming family property, they had to be clothed with the<br />

requisite capacity. The endorsement on the Writ of Summons read as follows:<br />

28

1. MADAM <strong>AKOSUA</strong> <strong>DUFIE</strong> PLAINTIFFS<br />

2. KINGSLEY ADU POKU-MENSAH<br />

(Customary successor to the late Kweku Poku For themselves and on behalf of<br />

the family of the late Kwaku Poku)<br />

It is apparent that the 2 nd Plaintiff was the customary successor of the late<br />

Kwaku Poku and this was admitted by the Defendants in their defence and<br />

testimony. Capacity is a point of law which if raised goes to the root of the<br />

action. The law on the position of a customary successor must then be examined<br />

to determine whether or not the 2 nd Plaintiff was clothed with the capacity.<br />

In GHANA MUSLIMS REPRESENTATIVE COUNCIL AND OTHERS v<br />

SALIFU AND OTHERS [1975] 2 GLR 246-265, the learned Judges held that<br />

in a representative action it was necessary, both in the writ and all<br />

subsequent pleadings to state clearly that the parties were suing or<br />

being sued in their representative capacity on behalf of the members<br />

of a defined class.<br />

It must be stated that the Plaintiff/Respondent had endorsed their Writ and<br />

pleadings as such and therefore no issue could be raised about the procedure or<br />

the capacity in which they sued.-<br />

In NYAMEKYE v ANSAH [1989-90] 2 GLR 152-163 it was held that as a<br />

general rule, the head of a family as representatives of the family was<br />

the proper person to institute suits for the recovery of family land. And<br />

where the authority of a person to sue in a representative capacity was<br />

challenged, the onus was upon him to prove that he had been duly<br />

authorized. He could not succeed on the merits without satisfying the<br />

court on that important preliminary issue. The customary law position<br />

was that when a successor was appointed, he was ipso facto the head<br />

of the immediate family. In the instant case, the 2 nd Plaintiff had been<br />

appointed the successor and therefore he became the head of the immediate<br />

29

family. He therefore had the capacity to sue and the judgment of the court of<br />

Appeal in that respect ought not to be disturbed.<br />

What weight then ought to be put on the conflicting evidence adduced<br />

by both parties?<br />

In the case of Yorkwa v Duah [1992-93] GBLR 278, CA, it was held that<br />

whenever there was in existence a written agreement and conflicting<br />

oral evidence over a transaction, the practice in the Court was to lean<br />

favourably towards the documentary evidence, especially if it was<br />

authentic and the oral evidence conflicting. See also Nsiah v Atuahene,<br />

[1992-93] GBLR 897 C.A<br />

It is interesting to note that in an action for a declaration of title to land, all the<br />

Plaintiffs were able to produce in support of their claim was a utility receipt<br />

dated January 1994 especially also as the burden of proof and persuasion rested<br />

firmly on them.<br />

The Defendants on the other hand have been able to produce enough<br />

compelling evidence to support their claim that the properties were the self<br />

acquired properties of the deceased. The Plaintiff claimed that the building was<br />

completed in 1955 whereas the Defendant tendered in Exh 4 dated 9-5-58 which<br />

was a receipt for the preparation of permit to develop Plot No 11 Block 24 which<br />

is the property in dispute.<br />

Other pieces of evidence which go to confirm that the deceased exercised overt<br />

acts of ownership more than the Plaintiffs were able to prove, are the following;<br />

1. It was not disputed that the deceased exercised overt acts of ownership<br />

over the properties without challenge from either the 1 st or 2 nd Plaintiff.<br />

He rented out the property to tenants and was never once called to<br />

account for the proceeds of the rent.<br />

2. He paid all the ground rent and property rates by himself without any help<br />

from anyone. All these acts go to support the assertion of the Defendants<br />

30

that indeed the properties were the self acquired properties of Kwaku<br />

Poku.<br />

In cross examination, the 2 nd Plaintiff was asked if he ever asked his brother<br />

about the title deeds to the properties and his answer was that he never did<br />

because the deceased was his elder brother and he didn’t have to ask him for<br />

the title deeds.<br />

Indeed this flies in the face of reason especially if as he claims he only put the<br />

deceased in charge because he was outside the country at the time. This<br />

assertion by the 2 nd Plaintiff is contrary to logic and his subsequent conduct in<br />

seeking to establish that the properties were family properties. His conduct any<br />

time he came back from the UK was inconsistent with someone who was<br />

financing or had financed the acquisition of the disputed properties.<br />

Indeed in the Defendants statement of case, learned Counsel for the Defendant<br />

strongly argued that both the Trial Judge and the Court of Appeal failed to<br />

consider the inconsistencies in the evidence of the Plaintiffs and their witnesses<br />

and rather tended to give weight to such inconsistencies contrary to the principle<br />

of law laid down in Odametey v Clocuh [1989-90]1 GLR 14 @ 28 S.C.<br />

3. The evidence of PW1 that she divorced the deceased Kwaku Poku<br />

because he did not give her a portion of the farm they cultivated together<br />

is telling and should have been scrutinized by the learned trial judge. If<br />

she knew that it was family property why would she be claiming a part<br />

when she was aware that she was not part of Kwaku Poku’s family and in<br />

her own testimony, this was the reason why she divorced the deceased.<br />

This in my view would rather corroborate Defendants assertion that the<br />

property was not family property but rather the self acquired property of<br />

Kwaku Poku.<br />

4. In addition to this, from the evidence on record, Kwaku Poku was never<br />

called upon to account for the proceeds from the cocoa farms in his<br />

lifetime, neither is there evidence on record to show that he of his own<br />

31

volition ever accounted to the family for the proceeds from the cocoa farm<br />

or for the Amakom property.<br />

All these pieces of evidence lead to one irresistible conclusion that the property<br />

was not family property.<br />

WEAKNESSES IN PLAINTIFFS CASE<br />

i. 2 nd Plaintiff also gave evidence that it was his sister the 1 st Plaintiff who<br />

connected utility services to the property in Amakom. P.W 3 also testified<br />

that he was responsible for connecting electricity to the house. In his<br />

testimony, he informed the Landlord Kwaku Poku and this was before 1 st<br />

Plaintiff came to live in the house. He also testified that 1 st Plaintiff<br />

refunded the money to him but does this refund of the money convert the<br />

property to family property? I don’t think so. Indeed in Ghana, it is not<br />

unreasonable nor uncommon for tenants to make certain improvements to<br />