JAVA Mar-2019

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

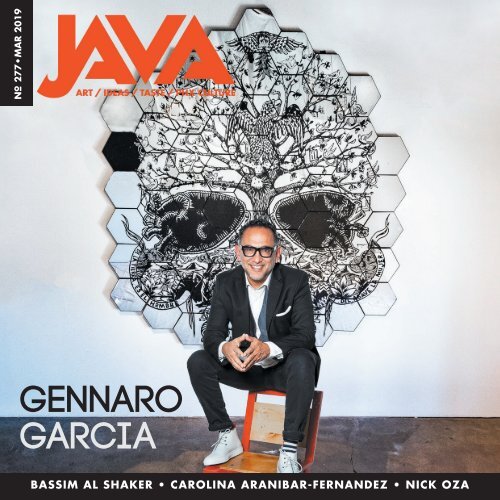

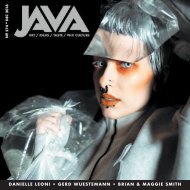

277 •MAR <strong>2019</strong><br />

GENNARO<br />

GARCIA<br />

BASSIM AL SHAKER • CAROLINA ARANIBAR-FERNANDEZ • NICK OZA

WONDROUS WORLDS<br />

ART & ISLAM THROUGH TIME & PLACE<br />

Discover more than 100 works of Islamic art from around the world and spanning a millennium.<br />

ON VIEW NOW THROUGH MAY 26<br />

PHXART.ORG<br />

CENTRAL + MCDOWELL<br />

@PHXART<br />

Wondrous Worlds: Art & Islam Through Time & Place is organized by the Newark Museum. Its premiere at Phoenix Art Museum is made possible through the generosity of the Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust Exhibition Endowment Fund, and supported by<br />

E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation, APS, and OUTFRONT Media. image credit (detail): Molded Luster Tile with Sentence Fragment in Raised Calligraphy, Floral, Avian and Geometric Motifs (detail), Kashan, Iran, first half of the 13th century.<br />

Molded fritware polychrome painted over white slip under transparent glaze. Newark Museum Gift of Herman A. E. Jaehne and Paul C. Jaehne, 1938.

NOVO AMOR<br />

Opening Act: Gia <strong>Mar</strong>garet<br />

Wed., <strong>Mar</strong>ch 6 | 7 p.m. | $28.50–$38.50<br />

“His melodic instrumental accompaniments<br />

pair perfectly with his Bon Iver-esque vocals,<br />

creating a beautiful flow to his songs.”<br />

—The Triangle<br />

Upcoming Concerts<br />

River Whyless and<br />

Darlingside<br />

<strong>Mar</strong>ch 17<br />

Omar Sosa and Seckou Keita:<br />

Transparent Water<br />

<strong>Mar</strong>ch 24<br />

Antonio Sanchez and<br />

Migration<br />

<strong>Mar</strong>ch 24<br />

SFJazz Collective:<br />

Music of Miles Davis<br />

April 4<br />

And many more!<br />

<strong>2019</strong> Concert Series sponsored by<br />

MIM.org | 480.478.6000 | 4725 E. Mayo Blvd., Phoenix, AZ

CONTENTS<br />

8<br />

12<br />

22<br />

30<br />

34<br />

FEATURES<br />

Cover: Gennaro Garcia<br />

Photo by: Juan Loza<br />

8 12 22<br />

34<br />

THE ART AND LIFE OF<br />

GENNARO GARCIA<br />

By Jeff Kronenfeld<br />

BASSIM AL SHAKER<br />

Opens Green Leaf Gallery<br />

By Rembrandt Quiballo<br />

KNIGHT LIFE<br />

Photography: Karl Millings<br />

Sara Krug, Ta Nee’ Townsend<br />

ARTIST CAROLINA<br />

ARANIBAR-FERNANDEZ<br />

From Bolivia to Arizona and Beyond<br />

By Morgan Moore<br />

PHOTOJOURNALIST<br />

NICK OZA<br />

Documenting Life on the Border<br />

By Tom Reardon<br />

COLUMNS<br />

7<br />

16<br />

20<br />

38<br />

40<br />

BUZZ<br />

Immigration and the Arts<br />

By Robert Sentinery<br />

ARTS<br />

Josef Albers in Mexico<br />

By Jenna Duncan<br />

Now Playing: Video 1999–<strong>2019</strong><br />

Mikey Foster Estes<br />

FOOD FETISH<br />

Sapiens Paleo French Cuisine<br />

By Sloane Burwell<br />

GIRL ON FARMER<br />

Fry’s Favorite<br />

By Celia Beresford<br />

NIGHT GALLERY<br />

Photos by Robert Sentinery<br />

<strong>JAVA</strong> MAGAZINE<br />

EDITOR & PUBLISHER<br />

Robert Sentinery<br />

ART DIRECTOR<br />

Victor Vasquez<br />

ARTS EDITOR<br />

Rembrandt Quiballo<br />

FOOD EDITOR<br />

Sloane Burwell<br />

CONTRIBUTING EDITOR<br />

Jenna Duncan<br />

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS<br />

Celia Beresford<br />

Mikey Foster Estes<br />

Kevin Hanlon<br />

Jeff Kronenfeld<br />

Ashley Naftule<br />

Tom Reardon<br />

PROOFREADER<br />

Patricia Sanders<br />

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS<br />

Enrique Garcia<br />

Karl Millings<br />

Sara Krug<br />

Johnny Jaffe<br />

Ta Nee’ Townsend<br />

ADVERTISING<br />

(602) 574-6364<br />

Java Magazine<br />

Copyright © <strong>2019</strong><br />

All rights reserved.<br />

Reproduction in whole or in part of any text, photograph<br />

or illustration is strictly prohibited without the written<br />

permission of the publisher. The publisher does not<br />

assume responsibility for unsolicited submissions.<br />

Publisher assumes no liability for the information<br />

contained herein; all statements are the sole opinions<br />

of the contributors and/or advertisers.<br />

<strong>JAVA</strong> MAGAZINE<br />

PO Box 45448 Phoenix, AZ 85064<br />

email: javamag@cox.net<br />

tel: (480) 966-6352<br />

www.javamagaz.com<br />

4 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE

THE HEARD MUSEUM PRESENTS<br />

ORGANIZED BY THE SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM FOUNDATION, NEW YORK<br />

ON VIEW NOW THROUGH MAY 27, <strong>2019</strong><br />

PRESENTING SPONSORS: The Diane and Bruce Halle Foundation, Virginia M. Ullman Foundation<br />

Heard Museum | 2301 N. Central Ave. Phoenix, AZ 85004 | 602.252.8840 | heard.org<br />

Josef Albers, Study for Homage to the Square: Closing, 1964. Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, Gift of the artist, 1969.<br />

© <strong>2019</strong> The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Partial funding provided by the Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture<br />

through appropriations from the Phoenix City Council.<br />

GALLERY<br />

EXPERIENCE IT<br />

BEFORE IT CLOSES<br />

NOW - MAY 12<br />

THE WINTER SHOW<br />

Through <strong>Mar</strong>ch 29, <strong>2019</strong><br />

Bassim Al Shaker, Bill Dambrova, CeCe Cole, Colin Chillag,<br />

Patricia Sannit, Catherine Cole, Abbey Messmer, Falah Saeedi<br />

Lisa Von Hoffner, Raypule, Rafael Navarro, Anthony Pessler<br />

Claire Warden, Charles Orme, Sean Deckert, Rembrandt Quiballo<br />

Fausto Fernandez, Jay Hardin, Joe Brklacich, Daniel Funkhouser<br />

Aileen Frick, Diyar Al Asadi, David Emitt Adams<br />

AMERICAN<br />

AIRLINES<br />

SPONSORED BY:<br />

SUNSTATE<br />

EQUIPMENT CO.<br />

TEMPE TOURISM<br />

OFFICE<br />

Open daily 10 am – 7 pm, First & Third Fridays until 10 pm<br />

Art classes, event & meeting space<br />

Call for an appointment 602 777 8646<br />

222 E McDowell Road Phoenix, AZ 85004

IMMIGRATION AND THE ARTS<br />

By Robert Sentinery<br />

BUZZ<br />

In the midst of the border wall debate, we look at how immigration impacts the<br />

Valley by specifically featuring artists who hail from other countries. There is no<br />

doubt that certain cities become artist magnets (think Paris in the 1920s), and<br />

the result is a cross-pollination of ideas and culture that ultimately makes for a<br />

thriving community. The four artists featured this month currently call Phoenix<br />

home but come from around the globe – Mexico, Iraq, Bolivia, and India.<br />

Gennaro Garcia was born in the Mexican city of San Luis Rio Colorado, Sonora,<br />

just across the border from Yuma. He grew up poor but with an artistic eye and<br />

a knack for making things. When Garcia became old enough to work, he helped<br />

with his family’s food cart, eventually building it into a brick and mortar. But he<br />

knew there had to be more for him.<br />

He came to the U.S. with nothing except his dual talents for making art and<br />

running restaurants, and he built a strong career encompassing both his<br />

homeland and his adopted one. Garcia’s artwork expands beyond traditional<br />

painting to ceramics, sculpture, and murals (many in high-profile restaurants<br />

here, on the West Coast, and in the Mexican art mecca of San Miguel de<br />

Allende). He has representation at half a dozen galleries across both countries<br />

and is co-owner of Taco Chelo restaurant in the heart of Roosevelt Row (see<br />

“The Art and Life of Gennaro Garcia,” p. 8).<br />

Bassim Al Shaker’s life is already well documented in sources like The New York<br />

Times. Having escaped persecution in his native Baghdad, Iraq, he found asylum<br />

here in the desert with the help of ASU’s visiting artist program. He has shown<br />

his work in prestigious international venues including the Venice Biennale and<br />

the Biennale of Sydney.<br />

Al Shaker has started a new venture, as a way of giving back to the city that<br />

welcomed him and his family – the Green Leaf Gallery. Located in a building<br />

adjacent to the Phoenix Art Museum that houses luxury apartments, it will help<br />

fill the void of professional galleries that represent the many talented contemporary<br />

artists in Phoenix (see “Bassim Al Shaker Opens Green Leaf Gallery,” p. 12).<br />

Carolina Aranibar-Fernandez is here by way of a year-long fellowship with<br />

ASU. Growing up in her native Bolivia, she experienced the Cochabamba<br />

Water War firsthand, where a California company took control of the city’s<br />

water supply and jacked up rates. This incident continues to inform her<br />

artwork. Her current project explores the impact of copper mining in Arizona<br />

and the ways in which private companies handle our natural resources (see<br />

“Artist Carolina Aranibar-Fernandez:From Bolivia to Arizona and Beyond,” p. 30).<br />

Nick Oza came to study in the U.S. from his native Mumbai, India, and his<br />

talent behind the camera kept him here. The recipient of numerous awards,<br />

including two Pulitzer Prizes, for his work with the Arizona Republic, Oza has<br />

achieved a career pinnacle. His current body of work covering border issues and<br />

the migrant caravan brings a great degree of humanity to a complex issue (see<br />

“Photojournalist Nick Oza: Documenting Life on the Border,” p. 34).

8 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE

For Gennaro Garcia, art is all around us,<br />

from the clothes we wear to the buildings<br />

we live in to the food – and tequila – we<br />

consume. Whether he’s designing murals for<br />

restaurants or leading tours of his studio for students,<br />

Garcia tirelessly spreads his gospel of creativity. His<br />

paintings, prints, ceramics, and woodwork grace the<br />

walls of three-star Michelin restaurants, nearly a dozen<br />

prestigious galleries spread across two countries, and<br />

the homes of collectors, where they even hang beside<br />

the works of his main inspiration, Frida Kahlo.<br />

Garcia also owns restaurants, counting a string of<br />

celebrity chefs as his friends and partners. In a<br />

time when walls have become lenses exposing<br />

America’s underbelly, Garcia shows that the<br />

Mexican and American dreams can share a border<br />

and a table, making all our lives a little happier and<br />

more colorful for it.<br />

Growing up poor in Mexico, for Garcia, creativity was<br />

a part of daily life. When he wanted toys, Garcia and<br />

his father made them out of whatever materials were<br />

available. As a teen in San Luis – a Mexican town<br />

across the border from Yuma – he painted signs for<br />

local businesses and helped his dad run restaurants.<br />

He honed the DIY ethos and down-to-earth style that<br />

are as much his trademarks as Tzompantli skulls and<br />

outstretched hands. He studied graphic design at a<br />

university in Tijuana and then returned to San Luis to<br />

take over his father’s restaurant, after the rest of the<br />

family moved to Yuma.<br />

Continually trading up from a small food cart to a<br />

larger one to an actual storefront, Garcia noticed<br />

that field workers a few hundred meters north in the<br />

U.S. were making more than he was as a restaurant<br />

owner. Like so many young and ambitious immigrants<br />

before him, he came to America with a dream and<br />

little else. Broke and with no connections, he slept in<br />

an alley for the first few weeks while he found a job<br />

and place to live.<br />

Later, Garcia painted murals on the walls and ceilings<br />

of the modest house his family rented. He took<br />

photos, to show local restaurant owners what he<br />

could do. Though at first he had no takers, Garcia<br />

eventually received his first commission to paint a<br />

mural for Mi Ranchito Restaurant in Yuma, where<br />

his art still graces the walls. Within two months of<br />

starting the project, he was hired as the restaurant’s<br />

general manager, a job he kept for five years.<br />

“The owner is like my second dad,” Garcia recalled.<br />

“His son was the best man at my wedding years later.”<br />

Garcia eventually met Briseida, an ASU student<br />

visiting Yuma. They quickly fell in love. After a few<br />

months, he moved to Phoenix and worked as a<br />

manager at a Mexican restaurant. Two years later, he<br />

told Briseida that he wanted to do art full-time. She<br />

encouraged him to pursue his dream, helping him to<br />

weather the drop in his income during the transition.<br />

“I think that’s something every artist needs,<br />

somebody that gives them support,” Garcia said.<br />

Garcia quit his day job and began painting at a<br />

furious pace, then working in a highly abstract style.<br />

In Ahwatukee, where he and Briseida still live, he<br />

found a coffee shop that let him display his art. A<br />

woman who liked what she saw contacted him,<br />

explaining that she ran a high-end interior design<br />

company and offering him a job doing what he loved:<br />

painting. Garcia honed his craft and style, working<br />

first as an apprentice and eventually as senior<br />

muralist. After five years, Garcia sold his stake in the<br />

company and finally married Briseida. He was ready<br />

to court the art world in a big way.<br />

His first gallery show was with Xico Arte y Cultura,<br />

now known as Xico Inc., whose mission is to “nourish<br />

a greater appreciation of the cultural and spiritual<br />

heritages of the Latino and Indigenous peoples of<br />

the Americas throughout the Arts.” The organization<br />

operates galleries at their headquarters on Buckeye<br />

Road as well as the container complex on Roosevelt<br />

Row. It was through Xico that Garcia first connected<br />

with Virginia Cardenas, who was on the nonprofit’s<br />

board. Virginia and her husband Jose are prominent<br />

local art collectors and supporters of Latino culture.<br />

Garcia resolved to see his works enter their extensive<br />

collection. He developed a friendship and deep<br />

admiration for the couple.<br />

“They used to come and see my art at festivals and<br />

galleries,” Garcia recalls. “They loved the art, but it<br />

took them two years to get one of my pieces.”<br />

Now six of his works grace the walls of the couple’s<br />

home, which Jose preserves in honor of Virginia –<br />

she died of kidney cancer in 2012. One of Garcia’s<br />

next big breaks came with a show at Calvin Charles<br />

Gallery in Scottsdale. Things went well, and he<br />

began lobbying hard for a solo show, which he got<br />

a few months later. At the time, he was only the<br />

second Latino to do so there. Knowing how vital<br />

the show’s success would be for his career, Garcia<br />

poured his own money and energy into promoting<br />

it, even taking out full-page ads in magazines. His<br />

efforts paid off: the show sold well and launched<br />

Garcia into a higher stratum of the art world.<br />

“After that one, most galleries came easily,”<br />

Garcia recalls.<br />

<strong>JAVA</strong> 9<br />

MAGAZINE

Garcia had also begun working with prominent<br />

spaces in Los Angeles, such as ChimMaya Gallery,<br />

an East L.A. fixture for up-and-coming Latino artists<br />

since 2005. At long last, he was achieving the<br />

success he had pursued for years. A gallery from<br />

New York reached out about doing a show there,<br />

and Garcia said yes. During a family celebration<br />

afterward, his father congratulated him on finally<br />

achieving his “American dream.” The comment<br />

lodged in Garcia’s head, leading him to deep<br />

introspection and precipitating something of an<br />

artistic crisis.<br />

“I was talking to my wife the next day and told her,<br />

‘Seriously, what happened to my Mexican dream?’”<br />

Garcia recalls. “I’m about to have the show of my life<br />

in New York, but nobody knows my name in Mexico.”<br />

Unable to dislodge the demon of doubt, Garcia<br />

made the bold move of cancelling the show. He had<br />

recently met and befriended Carlos Muñoz, a film<br />

director from Mexico City, whom he told about his<br />

decision one night while they shared tequila. “Oh<br />

pendejo, that’s stupid,” Garcia recalls his friend<br />

saying before breaking into a self-effacing laugh.<br />

However, Muñoz also understood Garcia’s desire to<br />

be true to his roots. He eventually accompanied the<br />

artist and filmed him as he journeyed across Mexico<br />

in search of gallery representation in his homeland.<br />

Garcia set his sights on San Miguel de Allende,<br />

drawn by the city’s unique history and beauty.<br />

Located in the central Mexican state of Guanajuato,<br />

San Miguel de Allende has a history of attracting<br />

artists from around the world, and was recognized as<br />

a UNESCO world heritage site in 2008. A friend and<br />

art collector he knew there took Garcia and Muñoz<br />

around town, introducing the artist to numerous<br />

gallery owners.<br />

After a series of rejections, the indefatigable Garcia<br />

finally found a gallery space. He carted his art across<br />

the border, and the show proved to be a critical and<br />

commercial success. After the show, when Garcia<br />

picked up the remaining items, a local art collector –<br />

who had acquired five trunks of art, journals, and other<br />

property purportedly belonging to Frida Kahlo (though its<br />

authenticity has been hotly disputed) – acquired Garcia’s<br />

remaining works. His gambit had paid off.<br />

Garcia continued to work in the U.S. at the same<br />

time, adopting a border-straddling existence he<br />

continues to this day, traveling between the two<br />

countries at least ten times each year for various art<br />

and business projects. Like his life, Garcia’s art fuses<br />

elements from both of the countries he calls home, as<br />

well as his twin passions of food and art.<br />

One example of this is his Hecho A Mano ceramics collection, which features a pair of open palms as the primary<br />

visual motif – sometimes connected to wrists tattooed with birds, webs, and roses – representing the way his<br />

parents worked with their own hands to feed Garcia and his siblings. After <strong>Mar</strong>cela Valladolid, a chef famous for her<br />

show on the Food Network, posted images of the plates to her social media accounts, Garcia saw orders on his web<br />

store skyrocket overnight.<br />

Garcia also began to study and collaborate with Mexican artists and craftsmen in the city of Pueblo, learning the<br />

city’s colorful tradition of Talavera ceramics, which he used to create a mosaic for the Four Seasons Resort in<br />

Scottsdale.<br />

Another transnational endeavor is Garcia’s work with chef Javier Plascencia, who helped Baja California become a<br />

mecca for foodies and wine aficionados from across the globe. In a business mashup worthy of the hippest urban<br />

enclaves in the U.S., the two are opening an art gallery/butcher shop.<br />

With plans to house the hams, chorizos, and other locally made artisan meats within a glass cube inside the space,<br />

Garcia explains that the project’s heart is two friends sharing their respective arts in one place. The shop will share<br />

a property with Plascencia’s Animalon, a dining experience located under a hundred-year-old oak tree, and Finca<br />

Altozano, another of the chef’s world-class restaurants.<br />

A little north of Baja, in La Jolla, California, Garcia has worked with George Hauer and Trey Foshee on both George’s<br />

at the Cove and Galaxy Taco, another pair of famous restaurants. The latter establishment invited Garcia to dust off<br />

his chef’s hat and participate in its Taco Takeover event, where a visiting chef (or artist/chef) occupies the kitchen for<br />

an evening.<br />

Garcia was somewhat reluctant at first, afraid his cooking skills were rusty, but luckily Aaron Chamberlin, a<br />

prominent Phoenix chef and restaurateur previously profiled in <strong>JAVA</strong>, volunteered himself and Suny Santana<br />

10 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE

to tag along for a road trip and guerilla-cooking<br />

expedition to California. On the way home, the trio<br />

discussed their love for the taco, a conversation that<br />

spurred them to partner in the creation of Taco Chelo<br />

on Roosevelt Row in Phoenix.<br />

Garcia “is one of the best marketers I know,”<br />

Chamberlin said of his friend and business partner.<br />

“He knows everybody, and that’s because of his<br />

passion for food. He understands food, and he<br />

understands restaurants. Another thing about<br />

Gennaro that makes him unique from the art<br />

perspective is that he’s very fast. When you’re in the<br />

restaurant business, you need everything two weeks<br />

ago. Those are the things that make him unique and<br />

relevant to restaurants and why he gets work through<br />

so many chefs.”<br />

Garcia currently splits his time about 50/50 between<br />

his design work – collaborating with everything<br />

from fashion labels to wineries and tequila<br />

distilleries – and studio art, juggling a staggering<br />

number of projects that keep him constantly on the<br />

go. While you might think this lifestyle could pose<br />

challenges for the father of a nine-year-old daughter<br />

(who, of course, is named Frida), the pair share a<br />

passion for art and Disney. Though Frida is still<br />

in elementary school, her own work has been<br />

featured in a half-dozen gallery shows, and it<br />

has sold well, as Garcia – her first collector and<br />

biggest fan – is quick to point out.<br />

During a night of dining with a group in<br />

California, one of the guests asked Garcia if he<br />

would be willing to discuss how he integrates<br />

creativity into parenting in front of a crowd, for<br />

a nice paycheck. Somewhat incredulous at first,<br />

Garcia finally understood when a friend explained<br />

that the man was vice president for Disney’s<br />

Latin American and Caribbean operations. Garcia<br />

accepted, and Disney footed the bill to fly him<br />

and his family to Mexico City, where he and Frida<br />

gave a presentation to a rapt crowd of Disney<br />

executives and creatives.<br />

When Frida was asked who her favorite princess<br />

was, she said she didn’t like princesses, but<br />

preferred the heroines from the Disney series “The<br />

Descendants,” which follows the younger relatives of<br />

some of the company’s most infamous villains. This<br />

led to her and her father flying to Mexico City again,<br />

where they created a mural to promote the film. In<br />

classic style, Garcia invited local graffiti artists to<br />

participate as well. As always, Garcia was acting as<br />

a bridge, this time between the rough-and-tumble<br />

world of Mexico City street art and one of the world’s<br />

largest entertainment companies.<br />

Garcia points to his own life as an example of the<br />

contributions immigrants can offer. For him, the<br />

border is a cultural crossroads, not a place for hate<br />

or lies. Ever sensitive to his surroundings, he laments<br />

the “visual contamination” that barriers on the border<br />

impose on communities along both sides. Now, his<br />

art literally helps block such aesthetic imperialism.<br />

In 2015, San Luis installed a series of 30 billboards<br />

featuring Garcia’s art in front of the metal barrier<br />

running along the border. Like his other projects,<br />

it embodies his commitments both to building<br />

community through art and infusing creativity into<br />

daily life.<br />

<strong>JAVA</strong> 11<br />

MAGAZINE

12 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE<br />

Photo: Rembrandt Quiballo

It’s another balmy winter evening around downtown<br />

Phoenix. There’s a DJ playing rhythmic<br />

music amid contemporary works of art and a<br />

throng of people in conversation. It’s First Friday,<br />

but we’re not on Roosevelt Row. The celebration is<br />

the opening of a new art gallery in a luxury apartment<br />

complex across from the Phoenix Art Museum.<br />

Bassim Al Shaker, the individual who made all this<br />

happen, is chatting up visitors, and there’s been a<br />

smile on his face since the doors opened. He knows<br />

to enjoy the moment, because as a young immigrant<br />

artist, nothing can be taken for granted.<br />

Al Shaker has come a long way from his hometown<br />

of Baghdad, and through it all, he has kept his positive<br />

outlook intact. The politically tenuous environment<br />

he grew up in and his near-death experience<br />

have been well documented in numerous publications,<br />

including The New York Times. The media<br />

portrayal of bombings in Iraq and neighborhoods in<br />

shambles is accurate; however, Al Shaker prefers to<br />

focus on Iraq’s rich history and the culture that has<br />

endured despite all the hardships. “The art is in our<br />

blood,” he said. “We’re the oldest country in the<br />

world. [Iraq] taught the world so many things. We<br />

taught the world how to write.”<br />

From the beginning, he was surrounded by family that<br />

had a great appreciation for the arts. “I come from<br />

an art family,” he said. “My uncles are all artists. My<br />

dad is an artist. My uncle was a famous drummer in<br />

the Middle East. They taught me a lot.”<br />

The young Al Shaker would draw every chance he<br />

got. He would draw at home or anywhere he could<br />

set his paper and pencil. He found himself in trouble<br />

for not showing up at his assigned classroom;<br />

instead, he would be in the studio drawing or painting.<br />

At an early age, Al Shaker already had the ability<br />

to render anything with precise detail. In fact, he<br />

drew so well he had to prove himself to a teacher<br />

when she did not believe he had created one particularly<br />

adept work. She told him to replicate the work<br />

in front of her. He not only replicated the image, but<br />

he improved upon it, finally convincing the teacher.<br />

This innate talent would allow Al Shaker to get into a<br />

specialized arts school. “This high school, they have<br />

music, they have actors, they have movies, everything,”<br />

he said. “Not everyone could go to this high<br />

school. You needed to have a test, and they apply<br />

every year more than eight hundred to a thousand<br />

students, and they accept just fifty to sixty. When I<br />

applied, in the beginning, my family, they didn’t know<br />

I applied to this school.”<br />

Al Shaker’s hard work and his willingness to bet on<br />

himself paid off when he was invited to an important<br />

art show that took place in Egypt. “I won a gold<br />

medal,” he said with a laugh. “It’s very funny, when<br />

I say gold medal, because I’m not a sport guy. I don’t<br />

know why they gave me a gold medal. It was for the<br />

most detailed painting in the Middle East.”<br />

After winning the award, Al Shaker returned to Iraq<br />

and attended the College of Fine Arts at the University<br />

of Baghdad. He would hone his craft to a point<br />

where he was chosen to be one of a select group of<br />

artists to represent the country of Iraq in the 55th<br />

<strong>JAVA</strong> 13<br />

MAGAZINE

Venice Biennale in 2013. This inclusion to the prestigious<br />

international exhibition would prove a catalyst<br />

for the young artist’s life and career. Gordon Knox,<br />

the director of the ASU Art Museum at the time, saw<br />

his work and invited Al Shaker to participate in the<br />

International Artist Residency Program at Combine<br />

Studios in downtown Phoenix.<br />

Al Shaker arrived in the U.S. speaking no English.<br />

Gradually, he is becoming more and more comfortable<br />

with the language. “When I came here, I started<br />

from zero. I don’t have a language. I speak ‘yes’ and<br />

‘no,’ and I speak ‘hello’ and from one to ten. The ASU<br />

Art Museum, they give me someone with me always.<br />

Her name is Layal Rabat. She’s from Syria, and she’s<br />

one of my best friends. She translated everything.<br />

She introduced me to all the people I know now.”<br />

Although Al Shaker was thankful for the assistance<br />

from the ASU Art Museum, his lack of mastery over<br />

the English language made him feel isolated early<br />

on. He endured an existential crisis when he stayed<br />

inside his home for ten days straight to really examine<br />

his decision to relocate halfway around the world<br />

and to ask if this would ultimately be beneficial to<br />

his art.<br />

“You know, when you come from all big festivals,”<br />

Al Shaker said, “all the media come to you, all the<br />

14 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE<br />

things. When you come here and then you feel alone,<br />

it’s just very hard, you know. You feel alone because<br />

the language. I decided, maybe I will go to [another]<br />

country in the Middle East because I can’t go back to<br />

Iraq, or maybe I will stay here and start from zero. So<br />

I stayed here. I went outside, talked with the people.<br />

Just read one sentence or read a question and at<br />

home repeat it like ten times. Then go outside and<br />

just ask the people. So I hear them – what they talk<br />

about. From there I changed my life.”<br />

Al Shaker has had to be truly resourceful, moving<br />

from one space to the next in order to continue<br />

making art. After a productive stint in the residency<br />

program at ASU, he committed to staying in the U.S.<br />

and moved to Grant Street Studios. He was able to<br />

have a show and paint at 720 Gallery briefly, but<br />

had several of his works stolen during a break-in. He<br />

worked at a studio in Bentley Projects and had a special<br />

exhibition of portrait works depicting his biggest<br />

supporters. He opened Babylon Gallery on Roosevelt<br />

Row and found some stability to practice his craft as<br />

he continued to teach art around the Valley.<br />

His next venture took him to another artist residency,<br />

this time at Broadstone Arts District, a luxury<br />

apartment complex inspired by the arts. Al Shaker<br />

was brought in to do a four-month residency. After<br />

the complex sold to a different company – it’s now<br />

called the Green Leaf Arts District – the new owners<br />

decided to extend his residency indefinitely, and Al<br />

Shaker vowed to create a quality arts experience for<br />

his adopted city.<br />

He now paints in the complex and teaches art classes<br />

for tenants, as well as the general public. Although<br />

Al Shaker’s work area was originally more of a lounge<br />

than an actual art space, he envisioned a viable<br />

space where artists could show their work and be<br />

appreciated by art lovers.<br />

“My dream here is in Phoenix,” he said. “Baghdad<br />

is still my first love. But Phoenix is my second city,<br />

because when I walk in the street, I say ‘hi’ to everyone<br />

and they say ‘hi’ to me. When I go anywhere, I<br />

feel like I’m born here, so this is why it’s really amazing.<br />

And people here are lovely. I try to do something<br />

for the city, because we have very good artists, we<br />

have the space, and we just need to put up high-level<br />

art. We need more galleries.”<br />

Al Shaker puts his words into practice. After months<br />

of preparation overhauling the space and selecting<br />

art, he recently opened a group show in the newly<br />

minted Green Leaf Gallery, with some notable Phoenix<br />

artists. It was a rousing success.

TOP CHEFS<br />

41<br />

R E STAU RA N TS<br />

DESTINATION<br />

SCOTTSDALE<br />

CULINARY<br />

FESTIVAL<br />

APRIL 13-14<br />

<strong>2019</strong><br />

3<br />

STAGES<br />

LIVE MUSIC<br />

ALL WEEKEND<br />

FEATURING<br />

BERLIN<br />

W/TERRI NUNN<br />

Al Shaker will be having a solo exhibition of his most recent work in April. It has<br />

great emotional value to him in light of his beloved uncle passing away in a car<br />

accident. The experience has resulted in the artist experimenting with cutting<br />

and laying canvas on the floor. “I am doing this show for my uncle who died ten<br />

months ago,” Al Shaker said. “He’s really in my soul. When he died, I feel everything<br />

is broken in my life because I used to paint because of him.”<br />

Throughout all this, Al Shaker has been working diligently on an even more ambitious<br />

project. Consisting of large-scale paintings featuring musicians, the work<br />

comments on the dangers of religious intolerance. “I’m doing a series. It’s eight<br />

paintings, all of them [featuring] musicians. It’s not about the technique – it’s just<br />

about the idea behind it. I’m talking about all religion in the world. About how<br />

some people, they use religion to do whatever they want. It’s about what’s going<br />

on in the world now. These paintings, I’ve been sketching and reading about it<br />

more than seven years.”<br />

When asked if he practices a specific religion, Al-Shaker plainly states: “I’m an<br />

artist.”<br />

“I need to focus on my art,” Al Shaker said. “We didn’t come to this life to just<br />

fight. We didn’t come to this life to just, ‘Oh, I am Muslim, oh, you are Jewish,<br />

and, oh, you are Christian.’ No, we came to do something in this life. This life is<br />

very quick. We came to do something before we leave.”<br />

Scottsdale Civic Center Mall<br />

SAT APRIL 13 NOON - 9 PM<br />

SUN APRIL 14 NOON - 6 PM<br />

A WORLD OF FOOD, MUSIC & FUN<br />

FOUR PEAKS BEER GARDEN • TITO’S HANDMADE VODKA LOUNGE<br />

LIQUID ARIZONA presented by PHOENIX Magazine<br />

3 STAGES LIVE MUSIC including BERLIN featuring Terri Nunn<br />

VIP EXPERIENCE • CHOCOLATE & WINE • CULINARY DEMOS<br />

FAMILY FUN ZONE • more!<br />

TITLE SPONSOR<br />

ScottsdaleFest.org / tickets<br />

Green Leaf Gallery<br />

222 E. McDowell Road, Phoenix<br />

The Winter Show<br />

Through <strong>Mar</strong>ch 29th<br />

Bassim Al Shaker Solo Show<br />

Opening Reception: April 5, 6 – 11 p.m.<br />

@bassimalshaker<br />

www.bassim-alshaker.com<br />

SCOTTSDALE LEAGUE<br />

FOR THE ARTS, a 501(c)(3)<br />

supporting local arts<br />

programs since 1978,<br />

donates 100% of net<br />

proceeds to the arts.<br />

$4.5 million donated<br />

since 2000.<br />

Proud presenters of Arizona’s Tastiest Fundraisers:<br />

Burger Battle – <strong>Mar</strong>ch 22, <strong>2019</strong><br />

Cocktail Society – April 12, <strong>2019</strong><br />

Scottsdale Culinary Festival – April 13-14, <strong>2019</strong>

ARTS<br />

JOSEF ALBERS IN MEXICO<br />

By Jenna Duncan<br />

History can often influence movements in contemporary<br />

art, as evidenced by images of the ancients<br />

resurfacing in the works of Modern masters.<br />

Artistic influences of the past begin to meld with<br />

modern artists – Minimalists, Abstract Expressionists,<br />

and Bauhaus-era designers – particularly evidenced<br />

in the paintings, drawings, and photographs<br />

of Josef Albers. “Josef Albers in Mexico” is now on<br />

view at Heard Museum.<br />

This exhibit allows guests to view and consider the<br />

links between Meso-American architecture and ruins<br />

that Josef Albers explored during his travels and the<br />

way these sites influenced his practice for the next<br />

30 years, explains Lauren Hinkson, Associate Curator<br />

of Collections for the Guggenheim Museum in New<br />

York, where the show was organized.<br />

“Before Albers traveled to Mexico in 1935, he was<br />

not painting,” Hinkson said. “He took thousands of<br />

photos. You can see that he really studied elements<br />

of the pyramids and their designs.”<br />

Many revelations come in viewing the photography,<br />

Hinkson said. “We have included about sixty<br />

photos and photo collages in this show, many of<br />

which have not been seen in the United States,<br />

and rarely seen at all.”<br />

Works in the exhibit are grouped by architectural<br />

sites across Central Mexico and the Yucatan<br />

peninsula, including Chichén Itza, Mitla, Monte<br />

Albán, and Teothuacán. Josef and his wife,<br />

Anni Albers, also visited additional sites in<br />

South America, including Peru, but the spotlight<br />

was placed on Mexico for this show.<br />

“We wanted to focus on both the Guggenheim’s<br />

holdings and also what was available from the<br />

Albers Foundation,” Hinkson said. Many of the<br />

photos came from his namesake foundation. Most<br />

of the works, including the very familiar Homage<br />

to the Square series, have never been on view in<br />

Arizona prior to this show.<br />

Anni Albers was a well-known and influential<br />

designer and textile artist. Anni taught design theory<br />

to weavers at Bauhaus and later became the school’s<br />

acting director. From 1933 to 1949, she was head of<br />

the weaving department at Black Mountain College.<br />

She was recently recognized with a solo exhibition<br />

at the Tate in London from October 2018 to the end<br />

of January. She is seen in several of the photos and<br />

contact sheet collages.<br />

Hinkson says she discovered Albers’ photographs<br />

in the Guggenheim collection about 10 years ago<br />

and became very excited about them because<br />

they had not been shown. She connected with<br />

chief curator Brenda Danilowitz of the Albers<br />

Foundation, then planned and arranged for the collaboration.<br />

While much of the work comes from<br />

the Guggenheim collection, Hinkson also borrowed<br />

extensively from the Albers Foundation to<br />

complement, Danilowitz explained.<br />

In the arrangement of this exhibit, the juxtaposition<br />

of photos of geometric and serpentine patterns<br />

next to the paintings of Albers makes it easy to<br />

16 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE

see the influences in shape, texture, and hue. “He<br />

started experimenting using the colors of Mexico,”<br />

Danilowitz said, pointing out details of some of his<br />

older paintings.<br />

Some credit Albers for inspiring the Minimalist<br />

movement in art, and he is often noted for his work<br />

in color theory. Though Donald Judd called him the<br />

godfather of Minimalism, Albers probably wouldn’t<br />

have labeled himself that way, Danilowitz said. However,<br />

his teaching at Black Mountain College and Yale<br />

directly influenced a generation of artists, including<br />

Cy Twombly, Eva Hesse, and Robert Rauschenberg.<br />

“All of the ’60s artists knew about Albers. That<br />

is when he began to be seen as this old master,”<br />

Danilowitz said.<br />

Albers joined the Bauhaus school of art, design, and<br />

architecture in 1920 at age 32. He was one of the<br />

first students to become a meister, or master, Hinkson<br />

says. Due to pressures from the Nazi government, the<br />

school was forced to move from Weimar to Dessau<br />

and then Berlin in its final months. Josef, Anni, and<br />

many others fled Germany. After relocating to the<br />

United States, Albers became active at Black Mountain<br />

College in North Carolina and later settled in<br />

Connecticut to teach at Yale. He and Anni continued<br />

their travels through Mexico into the 1960s.<br />

Over the decades of their travel, the development<br />

of the tourism industry in Mexico is also chronicled.<br />

“When they first arrived in the 1930s, there wasn’t<br />

much,” Hinkson said. “In one of his tiny contact<br />

prints, you can see Josef Albers standing in front of<br />

a streamlined car, right next to a pyramid, because<br />

you could drive right up to the pyramids and walk<br />

right in.”<br />

At the Zapotec site, Monte Alban, in the 1940s and<br />

1950s, Mexican archeologist Alfonso Caso was<br />

in the process of excavating for years. This was<br />

particularly exciting to Josef and Anni because each<br />

time they returned, there was something new to see,<br />

Hinkson said.<br />

Another interesting part of this exhibit is the collection<br />

of a few well-preserved Pemex travel maps.<br />

These maps were produced by the state-run oil company<br />

to support the travel industry and designed as<br />

highly visual souvenirs.<br />

“Josef Albers in Mexico”<br />

Heard Museum<br />

Jacobson Gallery<br />

Through May 27<br />

heard.org<br />

Josef Albers (1888-1976), Study for Homage to the Square, Closing, 1964,<br />

Acrylic on Masonite, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, The<br />

Josef Albers Foundation, Inc., 1996<br />

Anni Albers (1899-1994), Josef Albers, Mitla, 1935-39, The Josef and Anni<br />

Albers Foundation, Bethany, Connecticut, 1976<br />

Josef Albers (1888-1976), Study for Sanctuary, 1941-1942, Ink on paper, The<br />

Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany, Connecticut, 1976<br />

Josef Albers (1888-1976), Ballcourt at Monte Alban, Mexico, ca. 1936-37, Gelatin<br />

silver print, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany, Connecticut, 1976<br />

Josef Albers (1888-1976), The Pyramid of the Magician, Uxmal, 1950, Gelatin<br />

silver print, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, The Josef Albers<br />

Foundation, Inc., 1996<br />

Josef Albers (1888-1976), Luminous Day, 1947-1952, Oil on Masonite, The Josef<br />

and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany, Connecticut, 1976<br />

Josef Albers (1888-1976), Tenayuca I, 1942, Oil on Masonite, The Josef and<br />

Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany, Connecticut, 1976<br />

<strong>JAVA</strong> 17<br />

MAGAZINE

NOW PLAYING: VIDEO 1999–<strong>2019</strong><br />

Mikey Foster Estes<br />

To mark its 20th anniversary and commemorate its movie theater past,<br />

Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art presents an exhibition entirely<br />

focused on the moving image. “Now Playing: Video 1999–<strong>2019</strong>” brings<br />

together works by 11 international artists and samples both major<br />

contributions to video art and works from SMoCA’s collection. The exhibition<br />

highlights different aspects of video: its ephemerality, animation, and its<br />

relationship to narrative.<br />

Writing on the relationship between painting and cinema in 1967, French film<br />

theorist André Bazin distinguished the space of the picture frame from that<br />

of the screen. A painting, Bazin wrote, pulls our gaze inward, but the screen<br />

harnesses a centrifugal force that propels us outward. The moving image,<br />

unlike its still counterpart, exists in time, and in many cases blurs the line<br />

between reality and fiction.<br />

This exhibition poses an intriguing situation in which to view video. Instead<br />

of solely being secluded in darkened, soundproofed rooms or confined to<br />

a monitor via headset, the exhibition allows for sets of relationships and<br />

rhythms to take form. In one gallery, the metronomic sound of dribbling<br />

a basketball from a video by <strong>Mar</strong>k Bradford bounces through the space,<br />

becoming an acoustic aspect of other works in the room.<br />

The experiential light and projection works by Diana Thater and Aaron<br />

Rothman complement one another. Both artists are concerned with the<br />

natural landscape. Thater’s Orange Room Wallflowers contrasts nature and<br />

beauty with technology and artifice. Rothman’s slow-moving simulation of<br />

light moving across the wall plays with the viewer’s sense of orientation.<br />

Looking up toward the ceiling, you try to discern its cause – the skylight<br />

or the projector?<br />

Shirin Neshat’s Turbulent is in the next space over. Prior to seeing this<br />

installation at SMoCA, I had only seen poor reproductions of it on<br />

YouTube. It’s mesmerizing to see and hear. Upon walking in, the viewer<br />

is caught between two black-and-white videos that stand in for two<br />

opposing forces. In one, a man performs a traditional song in front of a<br />

full audience of other men; in the other, a female singer, Sussan Deyhim,<br />

delivers an ecstatic and deeply moving vocal performance with no<br />

audience. For Neshat, this duel of opposites highlights the inherent social<br />

and political gap between genders in Islamic Iran.<br />

A second gallery contains a total of eight looping videos by four different<br />

artists, all of which clock in at under four minutes. The display of these<br />

is reminiscent of that of painting, in that the moving images exist on a<br />

picture plane and in relation to one another. One can quickly hop from<br />

18 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE

one to the next or devote a few minutes to each. These images, unlike<br />

painting, seem to morph in time endlessly.<br />

The animations on view by Christian <strong>Mar</strong>clay provide one such example.<br />

At first, each work seems to be a catalog of images: chewing gum, bottle<br />

caps, cigarette butts. Minutes in, the images start to transform into<br />

playful flipbook narratives. The blotches of chewing gum on the sidewalk<br />

split and multiply like a culture of microscopic cells. The bottle caps of<br />

different colors and brands seem to remain still on an ever-changing<br />

ground. The cigarette butt slowly inches back up to completion, only to<br />

dwindle down again.<br />

Simpson Verdict, a short animated video by Kota Ezawa, is based on footage<br />

from the O.J. Simpson trial. The audio of the verdict, playing from a<br />

speaker above, is stark against the cartoonish and flattened image of<br />

Simpson’s response to the verdict. The trial was a media event – even if<br />

you didn’t particularly follow it, you knew about it. The video speaks to<br />

the way reality is rendered and compressed by popular culture.<br />

Candice Breitz’s large-scale video installation in the next room, Love<br />

Story, similarly approaches media imagery. The setup itself is like a movie<br />

theater. In separate clips, Alec Baldwin and Julianne Moore appear on<br />

set in front of a green screen, each telling tidbits of an emotional<br />

tale of escape. Almost immediately, we know they are acting, but the<br />

question is: As who? Behind this Hollywood rendition is another set of six<br />

screens and narrators who are refugees, but here they are telling their<br />

own unedited stories. Only when the curtain is pulled back completely do we<br />

have the opportunity to truly empathize.<br />

“Now Playing: Video 1999–<strong>2019</strong>”<br />

Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art<br />

Through May 12<br />

smoca.org<br />

Candice Breitz, “Stills from Love Story,” 2016, Featuring Julianne Moore and Alec Baldwin<br />

Top: Shabeena Francis Saveri, Sarah Ezzat <strong>Mar</strong>dini, Mamy Maloba Langa / Bottom: José <strong>Mar</strong>ia<br />

João, Farah Abdi Mohamed, Luis Ernesto Nava Molero.<br />

7-Channel Installation, Commissioned by the National Gallery of Victoria, Outset Germany + Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg<br />

Courtesy: Goodman Gallery, Kaufmann Repetto + KOW<br />

<strong>Mar</strong>k Bradford, “Practice,” 2003, single channel video; Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth<br />

Song Dong (b. 1966, Beijing, China, where he lives and works)<br />

“Floating: Scottsdale,” 2005, Video projection, Duration: Left screen 21:38, right 17:16<br />

Collection of Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art<br />

Purchased with funds from Mai Yahn, Richard Hayslip and Sara and David Lieberman<br />

Mika Rottenberg, “Sneeze,” 2012, Single channel video; Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.<br />

Kota Ezawa, “The Simpson Verdict” (still), 2002; Courtesy of the artist and Haines Gallery, San Francisco<br />

Diana Thater, “Orange Room Wallflowers,” 2001; Courtesy of the artist and 1301PE, Los Angeles<br />

<strong>JAVA</strong> 19<br />

MAGAZINE

SAPIENS PALEO FRENCH CUISINE<br />

By Sloane Burwell

Fusion cuisine usually involves a mish-mash of cultures that follows the<br />

movement of people with regional influences, like Cuban Chinese food<br />

found on the East Coast. Sometimes it’s fun and trendy, like Mexican sushi.<br />

Sometimes it’s a food analog, like vegan wings. Sometimes it’s strange and<br />

inexplicable. Like French Paleo.<br />

The paleo diet is jokingly referred to as the Caveman diet, with a focus on<br />

meats and some veggies, eschewing things like dairy and grain – since our preagricultural<br />

ancestors wouldn’t have had access to cheese and bread. So how<br />

would that work for French food, where the focus is often on precisely that,<br />

cheese and bread?<br />

Quite well, actually. Sapiens Paleo Kitchen is a French restaurant, perched in far<br />

North Scottsdale. For me, it’s a destination spot, since it’s easily a 40-minute<br />

drive from my super central domicile. When I heard of its opening, I was more<br />

intrigued than excited. I’ve been on Team Keto for quite a while. The keto diet is<br />

essentially paleo with dairy, and they’ll take my dairy when they pry it from my<br />

cold, dead fingers.<br />

Located in a fancy, modern, albeit small strip mall, Sapiens seems like any nice<br />

restaurant. There are about 16 tables inside. The interior is decorated in dark gray,<br />

with appropriately smooth music playing, and it’s packed with families, couples,<br />

and muscle-y CrossFit types. On my visit, it was a BYO situation, and most tables<br />

were happily sipping away.<br />

We started with coffee ($3.50), which comes with almond milk and a shot of MCT<br />

for a $1 upcharge. MCT, or medium chain triglyceride, is essentially fractionated<br />

coconut oil (coconut oil with a molecule removed to keep it from solidifying). It<br />

does give a surge of energy, but it’s challenging to stir pure oil into coffee – it<br />

needs the help of a blender. We make it work, but have to stir furiously lest the<br />

first sip be nothing but coconut oil.<br />

Our charming server engaged us immediately to find out why we were there.<br />

It appears that all of the servers are on the paleo diet, as we heard similar<br />

conversations repeat throughout the evening. Since I’m keto, she advised how we<br />

could add cheese or butter to dishes. So we did.<br />

It would be nearly criminal to skip Escargot ($15) at a French restaurant, so we<br />

didn’t. A cast iron crock comes to the table with more than half a dozen snails,<br />

with a king’s ransom of garlicky herb butter goodness. There are some paleo<br />

bread slices (more on that later) served alongside for scooping, lest anything go<br />

to waste. And it shouldn’t – this dish is quite fabulous, herbaceous, and garlicky<br />

enough to ward away vampires. All conversation ceased while we dug into it, only<br />

stopping long enough to gasp for air before it was gone.<br />

I feel the same way about French Onion Soup ($9), partially because it’s my<br />

favorite of all the soups, and because I make a mean one. So do they. And since<br />

we’re fine with dairy, we had the Gruyère cheese added on top. I’ll own up to<br />

being a tiny bit disappointed when it came out – I’m used to a bubbling mass of<br />

cheese. What felt skimpy was actually about right – turns out if the broth and<br />

onions are this delicious, the cheese isn’t as important. The salty, sultry, deeply<br />

flavorful broth takes two days for them to make, and the hard work wasn’t lost<br />

on us. The dollop of melty cheese gave a bit of textural interest. And flavor. Who<br />

doesn’t love cheese?<br />

Of course, when I saw the Paleo Bread Platter ($10), we had to order it. A<br />

charming tray containing fresh French butter, artichoke dip, and tomato jam is<br />

served along with several types of paleo “bread.” Only one could be classified<br />

as bread, and it was closer to a toast point than a slice of French bread. The<br />

consistency was a bit dry, as one would expect bread analogs to be, but it was<br />

perfect for smearing butter and the other dips on top.<br />

There were two other breads, but I would say they were more like crackers you’d<br />

find at a fancy specialty store. And they worked for the tasty tomato jam – a savory<br />

spread closer in taste to a bruschetta topping. The artichoke dip was great – warm,<br />

savory hunks of chopped artichoke hearts surrounded by ghee, garlic, and onions,<br />

paired perfectly with their fancy cracker-bread.<br />

I adored the Duck Confit ($26), an engaging dish of duck cooked in duck fat until it<br />

essentially falls apart. Here, it is as French and fabulous as you would hope, and<br />

I only knew it was paleo because of the sides – a gratin of parsnip and roasted<br />

seasonal veggies. Both were tasty and delicious.<br />

Curious about Paleo Meatloaf ($18), I tried theirs. A solid hunk of grass-fed beef<br />

arrives on the plate, surrounded by potato gratin and the aforementioned veggies.<br />

It’s worth noting that none of their gratins have cream or cheese. They are cooked<br />

with flavorful stock and coconut oil. Somehow, there is no coconut taste or smell,<br />

and the dish still manages to taste as creamy as you would expect its French<br />

counterpart to be, even without dairy. Their gratins are inscrutably delicious.<br />

Since we’d taken the leap of faith to drive this far – and no one in our party had<br />

ever tried it – we went all in for the Liver and Onions ($25). An impossibly large<br />

serving of at least six slices of medium rare liver appeared before us, in a silky<br />

sauce, surrounded by mounds of sautéed onions. We all looked at each other before<br />

I went in first. It was great.<br />

As our server explained, liver is one of the most healthful meats one can consume.<br />

It’s full of minerals and nutrients. To be fair, some of my friends found it a bit too<br />

mineral-y, but that is what liver tastes like. You can taste the pâté that is made out<br />

of this, in a sense, in that the rich flavors are on the top of your tongue. If you eat<br />

pâté, you should try liver and onions. And if you haven’t tried liver and onions – this<br />

is the place to do it. The sherry sauce in this dish is plate-lickingly fabulous, and<br />

let’s be frank – who doesn’t love sautéed onions?<br />

As for dessert, every server recommended the same dish – Apple Crisp ($8). Warm,<br />

soulful apples are sautéed in cinnamon, ghee, and spices, and served piping hot. At<br />

the bottom of the dish was the crisp – noted on the menu as “crunchy topping.” It<br />

was crunchy, and it was okay. I didn’t think it added much to the dish. I would have<br />

happily enjoyed the warm sautéed apples on ice cream. I’m sure there is a Paleofriendly<br />

version somewhere, and that would really make this a special dish. It’s<br />

good; I would eat it again. But it could be great.<br />

So is it possible to enjoy the fruits of a French paleo restaurant if you aren’t paleo?<br />

Absolutely. Sapiens Paleo Kitchen is a sweet restaurant serving excellent French<br />

classics.<br />

Sapiens Paleo Kitchen<br />

10411 E. McDowell Mountain Ranch Rd., Suite 120, Scottsdale<br />

(480) 771-5123<br />

Tuesday – Saturday 4 p.m. – 10 p.m.<br />

Closed Sunday and Monday<br />

<strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE<br />

21

22 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE<br />

Knight Life

23 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE

24 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE

25 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE

26 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE

27 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE

28 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE

Photographers:<br />

Karl Millings<br />

Sara Krug<br />

Ta Nee’Townsend<br />

Models”<br />

Tondra Dene’<br />

Simon Rohrich<br />

Ta Nee’Townsend<br />

Hair and makeup:<br />

Christine De Angelis<br />

Assistant<br />

Jesse Joseph Fairchild<br />

<strong>JAVA</strong> 29<br />

MAGAZINE

Artist Carolina Aranibar-Fernandez<br />

From Bolivia to Arizona and Beyond<br />

Text and portraits<br />

By Morgan Moore<br />

30 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE

Carolina Aranibar-Fernandez comes to Arizona from<br />

Bolivia, where she started her life of art at the<br />

age of eight. Her passion and work are driven by<br />

the mapped relationship between people, capital, and<br />

place, and fueled by history and current events.<br />

Bolivia’s famous Water War was one of the sparks<br />

for Aranibar-Fernandez’s body of work, in which<br />

she questions systems of colonization, capitalism,<br />

commodification, and extraction. She grew up at the<br />

time California-based Bechtel took control of her<br />

country’s water and spiked the rates, causing outrage<br />

and protest among Bolivians. She found herself<br />

questioning, then and years after, how a company<br />

so far away from a community could have so much<br />

power over it.<br />

Ten years ago, she left Bolivia to attend art school in<br />

the United States. Since then, her questions and art<br />

have taken her to Virginia, Qatar, Nepal, the Amazon,<br />

Brazil, back to Bolivia, and Arizona, and will take her<br />

soon to Florida.<br />

In each place her work leads her, she first waits<br />

for an invitation to enter the space. She comes<br />

to collaborate, not to work. She takes care not to<br />

perpetuate the colonialist habit of self-inserting<br />

and forcefully exploring for the sake of art. Instead,<br />

she builds relationships with the community, asks<br />

questions, and listens. Her goal is to create dialogue<br />

and form connections with the viewers of her pieces<br />

as well as with the communities with which she<br />

collaborates. Sometimes she engages in with a<br />

community for over a year before starting a piece – or<br />

doesn’t start a piece at all.<br />

Her work projects questions of power and how it<br />

manifests. Often formed as multi-media installations,<br />

Aranibar-Fernandez’s art immerses viewers into<br />

the behind-the-scenes world of production and<br />

extraction. She creates rooms that illustrate, by<br />

engaging almost every sense, the duality of a journey<br />

– between commodity and person – out of the earth,<br />

through the sea, and into a foreign land. Video<br />

projections and audio composites are mixed with<br />

textiles, ceramics, weaving, and beading, merging<br />

traditional forms of storytelling and creation with<br />

more contemporary and processed media.<br />

As an artist within an imperialistic, neocolonialist,<br />

and capitalistic society, she strives to exist inside – but<br />

against – this system, or, as the Peruvian sociologist<br />

Aníbal Quijano asserts, “vivir adentro y en contra.”<br />

This is demonstrated aptly through her exhibited<br />

work, commonly installed in colonial institutions<br />

(art galleries). Viewers unwittingly participate in<br />

destroying the work they experience, dropping its<br />

perceived value rapidly – sometimes simply by<br />

walking into the room. No single piece she has made<br />

still exists in physical form, to reject any attempts<br />

at commodifying an art piece made to question<br />

commodification.<br />

The unperceived value of her work is her process.<br />

Vulnerability threads itself into her regimen as<br />

she visits male-dominated mining sites through<br />

discomfort during deep dives into research. She also<br />

embraces vulnerability to ensure her work reflects<br />

the experiences of others above her own. Whether<br />

it’s silver-leafed coins made of quinoa and cocoa in<br />

Bolivia, or sugar molded in Brazil to model gold bars,<br />

Aranibar-Fernandez makes a point to work with those<br />

impacted by exploitation of these commodities as she<br />

fabricates her pieces. Each small part of the work is<br />

painstakingly handmade in collaboration with local<br />

working-class women of color, who engage in hours<br />

and hours of dialogue with her that in turn informs<br />

the rest of her process, from beginning to end.<br />

The women in these communities are crucial to<br />

Aranibar-Fernandez’s messages. They are directly<br />

impacted by the exploitation of their countries’<br />

resources, be it minerals and food commodities in<br />

Bolivia and Brazil, physical labor in Nepal, or oil and<br />

gas in Qatar. They are, as she affirms, the “most<br />

invisible labor.” She not only collaborates with them<br />

to make her work but also illustrates their stories<br />

visually and aurally.<br />

Women also exhibit a more ideal distribution of power<br />

than what is seen in the typical realm of capitalism.<br />

“If power is not only a ladder, rather a web, I think<br />

we could move differently in the world. And I think a<br />

lot of decisions in the capitalist system that we live<br />

in create an individual, egotistical ladder that I find<br />

very problematic.” Aranibar-Fernandez continues,<br />

“Redistributing power is really important. And in thinking<br />

about community, women have – for thousands of years<br />

– shown that when you work in community, there’s no<br />

ladder in the structure of power.”<br />

Elevating women and sharing their histories is<br />

only one, albeit a significant, facet of Aranibar-<br />

Fernandez’s work. She also wants to introduce

people to the layers of place, and to give thought to how hierarchies of power shape<br />

history and mythology.<br />

“Space – every place we go, and every land we step – has layers of history,” she<br />

explains, and her intent is to uncover the history not rewritten by colonists but shared<br />

by the people who were born and raised on the land – those who live here today<br />

and their ancestors. History indigenous to many of the places Aranibar-Fernandez<br />

has visited is considered mythology by Westerners, who use their position of power<br />

to frame their own narratives as objective history and discredit others. Aranibar-<br />

Fernandez learns as much as she can about the history of a place through reading,<br />

as well as through oral stories told by members of the communities she collaborates<br />

with, before settling on an idea for a project.<br />

She also uses place to differentiate forms of movement and exploitation. On the land,<br />

she analyzes resource extraction in mining, agriculture, and construction. But she also<br />

uses place as negative space – an opportunity to discuss what’s between places. That<br />

is why her work has also always been rooted in and across bodies of water; she is, in<br />

many of her pieces, “exploring depth in the ocean.”<br />

Perhaps Bolivia’s Water War served as a precursor to her consideration, as she has<br />

examined water as both a commodity and a plane on which to travel and to assert<br />

dominance. One of her first forays into this concept was working in and near<br />

the ports of Norfolk, Virginia, where she began to (and still to this day does)<br />

shed light on the trafficking of capital and bodies across the Atlantic.<br />

While Aranibar-Fernandez is sharing insight into the backbreaking realm of<br />

extraction, she is also revealing the aftermath of it, both in the transport and<br />

the destination. Her work has taken viewers from the silver mines of South<br />

America across meticulously traced routes to the importing nations of Europe.<br />

She has tracked the traffic of blue-collar workers from Nepal to Qatar, where<br />

they are all but held hostage to build modernity on top of the rich history that<br />

once was there. She illuminates the consequences of destroying value to<br />

construct wealth.<br />

In Arizona, Aranibar-Fernandez delves into the narrative of extraction with one<br />

of our state’s five Cs: copper.<br />

Arizona’s copper mining narrative does not look quite like the silver mining<br />

narrative in Bolivia. Where, in the latter, the country’s resources were stripped<br />

to form another’s (Spain’s) currency, the modern-day copper narrative in Arizona<br />

represents one of dominance and control. Aranibar-Fernandez is delving<br />

into the power dynamics of copper companies that hold influence across<br />

32 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE

the world, and she is only just starting to form her<br />

representation of it.<br />

She has, since August of 2018, immersed herself in<br />

research and conversations revolving around copper,<br />

how its value is perceived across the globe, who<br />

takes it from the ground, where it goes, and who<br />

profits. As she unearths Arizona’s role in the mineral’s<br />

commodification, she is learning new things about<br />

her place in the world, as well as in her own family.<br />

She discovered only recently that her grandfather<br />

was a miner in Bolivia, pulling from the earth silver<br />

and estaño (tin) in a small, rural town she had never<br />

previously considered visiting. Consistent with her usual<br />

form, the information came about through questioning<br />

and conversing with the town’s community.<br />

During her time here, Aranibar-Fernandez has also<br />

developed a relationship with the Copper State that<br />

she has not established with any other place outside<br />

of Bolivia. She rejects any singular term to describe<br />

her identity (not simply an immigrant, not simply<br />

a Bolivian), and this emerges in her sentiments of<br />

belonging, as well. While she considers Bolivia a<br />

home due to her roots, family, and ancestors, Arizona<br />

has presented a similar feeling.<br />

“I feel like since I’ve arrived, my body feels at home<br />

here, and that hasn’t happened before, in a place that<br />

wasn’t Bolivia. I feel that here. It seems like it comes<br />

from… I don’t know. I feel it really inside; it feels<br />

more like home. Arizona is very special.” Ancestral<br />

energy, the weather, the heat, and something still<br />

untouchable connect her to the state, in addition to<br />

human connections.<br />

The politics of a border state has created a sense<br />

of belonging for her unwavering questions. The<br />

effect of power on place exhibits itself in the historic<br />

displacement of indigenous people and people of<br />

color for mining, and the contamination of tribal<br />

and reservation waters when minerals are washed<br />

of their toxicity. Like Bolivia, Brazil, Qatar, Nepal,<br />

and other disenfranchised countries, Arizona is not<br />

unfamiliar with this historical trend. But while it<br />

houses groups marginalized as a result of extraction<br />

and commodification, it also houses the agents who<br />

act to marginalize. In exploring the disparate nature<br />

of a place’s relationships, Aranibar-Fernandez’s art<br />

becomes as multidimensional as the histories and<br />

mythologies she works to unearth.<br />

She views Phoenix as an important space for<br />

community and conversations. As with every place<br />

she has worked, she feels lucky to have mostly<br />

experienced receptivity to her art. She joins Arizona’s<br />

community through the ASU Herberger Institute’s<br />

Projecting All Voices Fellowship, which seeks to<br />

promote equity and inclusion in the arts by upholding<br />

spaces for discourse and representation. At the same<br />

time, any resistance, discomfort, or rejection of her<br />

work is viewed just as positively, and resounds with her<br />

own discomfort and vulnerability in making the pieces.<br />

Aranibar-Fernandez has experienced the privatization<br />

of a country’s resources and the effects spurred from<br />

it, and she observes this still happening throughout<br />

the world, displacing and transporting people and<br />

things from one side of the ocean to the other.<br />

She can feel the state our society is in, and while<br />

conversations may be changing, she doesn’t think the<br />

structure is – at least, not fast enough.<br />

With her work, she wants people to become<br />

conscious of the movement of people, resources, and<br />

narratives. Of those viewing her work, she doesn’t<br />

expect radical change, but smaller movements and<br />

conversations that may someday be catalysts to<br />

something larger.<br />

“My biggest goal is to make and ask questions,”<br />

she concludes. “If every viewer can leave with a<br />

question, that’s amazing.”<br />

<strong>JAVA</strong> 33<br />

MAGAZINE

34 <strong>JAVA</strong><br />

MAGAZINE<br />

Photo Sean Logan

Images can tell stories that transcend time and history, align our collective<br />

souls, or change our minds completely. Photojournalist Nick Oza, who has<br />

worked for the Arizona Republic since <strong>Mar</strong>ch of 2006, is not only locally known<br />

but an internationally esteemed two-time Pulitzer Prize–winning photographer.<br />

To say Oza’s resumé is impressive is an understatement. The Mumbai, Indiaborn<br />

journalist is a humble yet steadfast arbiter of truth in a world weary from<br />

misinformation and “fake” news. When everyone with a smartphone can be a<br />

photographer, it takes a special talent to make photos that evoke real feelings,<br />

images that inspire viewers to think about their own place in the world and<br />

empathize with others they may never meet. Oza possesses this ability, and his<br />

talent behind the viewfinder is something to be celebrated, even when his images<br />

echo a world we do our best to ignore.<br />

Old enough to know better, but young enough to burn the candle at both ends,<br />

Oza is, by his own admission, part of a dying breed. While good storytelling will<br />

always be an important aspect of humanity, the type of in-depth journalism Oza<br />

espouses is on life support. Over the coming decades, only time will tell if there is<br />

any hope for revival.<br />

Recently Oza learned that he will be receiving a grant from the National<br />

Geographic Society to continue documenting immigration issues in the Americas,<br />

so – luckily for all of us – he will be able to persist in making photos that capture<br />

the spirit of truth.<br />

We caught up with Oza to talk about his life, immigration, and what comes next.<br />

So, Nick, where did you grow up?<br />

I grew up in Mumbai. They used to call it Bombay.<br />

And how long did you live in Mumbai?<br />

I lived there until my twenties. I came here when I was 22, in 1989.<br />

So, thirty years here. What were your expectations when moving to the U.S.?<br />

It was, for me, an opportunity. I knew I wanted to be a photographer, but my<br />

whole notion was to be a commercial photographer. When migrants come here,<br />

their focus is to be successful with money. That’s why they’re coming to a foreign<br />

land. But my professors changed my mind after seeing the way I interacted with<br />

my subject matter. And they said I had a gift of getting closer to people, and<br />

having people trust me, so I should go into documentary work and journalism.<br />

Was that anything you had previously thought about doing while growing up?<br />

Honestly, I grew up being very shy, and people knew I didn’t like to talk much.<br />

Journalism just opened my mind on another level. As my work is maturing, I’m<br />

so grateful that the Arizona Republic editors gave me the opportunity to explore<br />

immigration issues.<br />

So, in a way, photography is becoming a smaller segment for me, and storytelling<br />

is becoming the bigger picture. I spend tremendous hours and have a reputation<br />

for working nonstop. I work on sensitive issues like immigration, mental health,<br />

women’s issues, the opioid crisis, and all of that takes time to fully immerse

yourself. You have to gain their [the subject matter of the images] trust. That’s why I<br />

spend more time talking, almost like a preacher; then the photography follows. Trust<br />

is a big thing.<br />

So, if I’m hearing you correctly, you are pitching what you want to work on,<br />