2019 AGS Magazine_V5

Magazine for the 2019 Artisan Guitar Show

Magazine for the 2019 Artisan Guitar Show

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

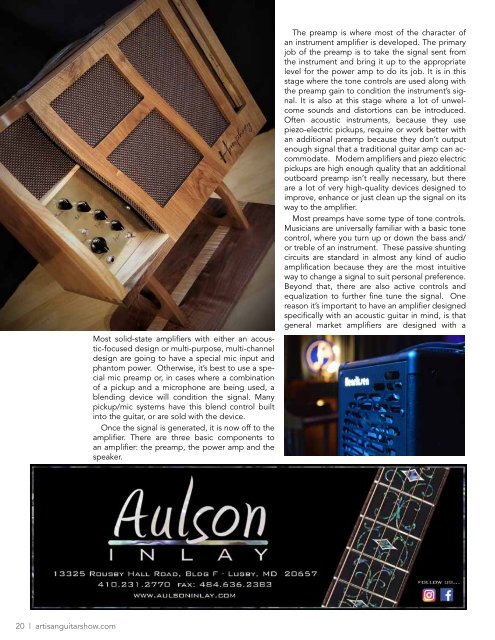

Most solid-state amplifiers with either an acoustic-focused<br />

design or multi-purpose, multi-channel<br />

design are going to have a special mic input and<br />

phantom power. Otherwise, it’s best to use a special<br />

mic preamp or, in cases where a combination<br />

of a pickup and a microphone are being used, a<br />

blending device will condition the signal. Many<br />

pickup/mic systems have this blend control built<br />

into the guitar, or are sold with the device.<br />

Once the signal is generated, it is now off to the<br />

amplifier. There are three basic components to<br />

an amplifier: the preamp, the power amp and the<br />

speaker.<br />

The preamp is where most of the character of<br />

an instrument amplifier is developed. The primary<br />

job of the preamp is to take the signal sent from<br />

the instrument and bring it up to the appropriate<br />

level for the power amp to do its job. It is in this<br />

stage where the tone controls are used along with<br />

the preamp gain to condition the instrument’s signal.<br />

It is also at this stage where a lot of unwelcome<br />

sounds and distortions can be introduced.<br />

Often acoustic instruments, because they use<br />

piezo-electric pickups, require or work better with<br />

an additional preamp because they don’t output<br />

enough signal that a traditional guitar amp can accommodate.<br />

Modern amplifiers and piezo electric<br />

pickups are high enough quality that an additional<br />

outboard preamp isn’t really necessary, but there<br />

are a lot of very high-quality devices designed to<br />

improve, enhance or just clean up the signal on its<br />

way to the amplifier.<br />

Most preamps have some type of tone controls.<br />

Musicians are universally familiar with a basic tone<br />

control, where you turn up or down the bass and/<br />

or treble of an instrument. These passive shunting<br />

circuits are standard in almost any kind of audio<br />

amplification because they are the most intuitive<br />

way to change a signal to suit personal preference.<br />

Beyond that, there are also active controls and<br />

equalization to further fine tune the signal. One<br />

reason it’s important to have an amplifier designed<br />

specifically with an acoustic guitar in mind, is that<br />

general market amplifiers are designed with a<br />

“scoop” built into their preamp, meaning the midrange<br />

frequencies are artificially turned down because<br />

when playing rock on an electric guitar those<br />

frequencies can become “muddy” and unpleasant.<br />

With acoustic guitars, or archtops and jazz music,<br />

you need those frequencies because you want a<br />

much more piano-like response.<br />

The preamp is really where there can be a real<br />

“art” to audio design. Different components can<br />

make a difference in whether something is dark<br />

or bright, even if they have the same specification.<br />

Just like choosing a type of wood, choosing<br />

a brand and type of capacitor can change the<br />

sound; for example going from a less expensive<br />

type of capacitor to a polypropelene capacitor will<br />

add brilliance to a sound, but the finer elements<br />

can even change greatly depending on the manufacturer<br />

and the individual components tolerances.<br />

Even something as simple as a different batch<br />

can make a difference in the sound and although<br />

subtle, not necessarily insignificant. This is typically<br />

where math and engineering take a backseat to using<br />

one’s ears to make design decisions.<br />

The next stage in amplification is the power amp.<br />

Power amplifier designs are a little more straight<br />

forward and have traditionally been broken into<br />

classes (A, A/B, etc…) but in the simplest terms,<br />

these days there are three basic types of power<br />

amplifiers on the market: Tube amps, traditional<br />

transistor solid-state amps, and class D (switching)<br />

amplifiers.<br />

Tube amplifiers are the oldest of the technologies,<br />

and their design is an art unto itself -- every<br />

little thing matters including where wires are<br />

placed when connecting components together.<br />

Solid state power amplifier architecture uses a<br />

transistor as opposed to a vacuum tube, reducing<br />

weight, size, cost and maintenance, but requiring<br />

more complex circuits. Most recently, class D amplifiers<br />

have become more available and are the<br />

predominant amplifier on the market for acoustic<br />

instruments as they put out the most efficient power.<br />

In the beginning, class D amplifiers had both<br />

quality and fidelity issues as well as noise problems<br />

when applied to instrument amplifiers (as opposed<br />

to consumer audio applications), but those problems<br />

are largely a thing of the past.<br />

When designing an amplifier for acoustic instruments,<br />

or any instrument where you do not want<br />

the signal to contain any distortion, you want as<br />

much power as is practical. The more power you<br />

have, the more volume and dynamic control you<br />

can get from the instrument without mud or distortion;<br />

however that brings with it size and weight.<br />

Class D amps are the most economical way to do<br />

this, but can be missing the analog warmth you get<br />

from a tube amp design. As with the preamp, this<br />

is where designs need the attention of the designer’s<br />

ears as much as anything.<br />

If weight is not so much of a concern, then a<br />

well-designed tube amp can deliver a few things<br />

that aren’t possible with even the most sophisticated<br />

digital circuitry. One of the unique characteristics<br />

of vacuum tube technology is that tubes can<br />

produce harmonics naturally. Why might this be<br />

important, and doesn’t this constitute some type<br />

of distortion of the input signal? A purist would say<br />

yes – it’s harmonic distortion, but when you take<br />

into consideration the loss of the “total” sound and<br />

nuances that a single-point pickup system doesn’t<br />

deliver to the amp, then it’s a reasonable trade-off.<br />

When playing your favorite acoustic guitar,<br />

you’re hearing all kinds of sounds coming not just<br />

from the sound hole, but from the sides, the back,<br />

the neck and the strings themselves. A lot of the<br />

complexity of that sound is lost when you use a<br />

single-point, or even a dual, pickup system that<br />

samples the sound from a very narrow space on<br />

the guitar.<br />

Vacuum tubes help by reintroducing some of the<br />

20 | artisanguitarshow.com<br />

artisanguitarshow.com | 21