Angelus News | June 3, 2022 | Vol. 7 No. 11

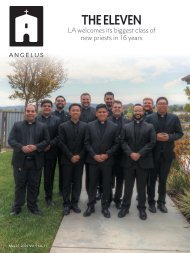

On the cover: The eight men set to be ordained priests for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles on June 4 are pictured outside the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels. Starting on Page 10, Steve Lowery tells their stories: where they come from, how they discerned their vocations, and what they have to say about the people they have to thank for helping them say yes to their special calling.

On the cover: The eight men set to be ordained priests for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles on June 4 are pictured outside the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels. Starting on Page 10, Steve Lowery tells their stories: where they come from, how they discerned their vocations, and what they have to say about the people they have to thank for helping them say yes to their special calling.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

equest.<br />

More broadly, the situation raises the<br />

larger question of the role and mission<br />

of Catholic journalism, both in St.<br />

Brandsma’s era and our own.<br />

<strong>No</strong>te that St. Brandsma’s arrest came<br />

in the context of relaying an order<br />

from the hierarchy to Catholic media<br />

about their editorial policies. In 1942,<br />

when most Catholic media outlets<br />

were directly owned by the bishops,<br />

and when the command-and-control<br />

model of episcopal leadership was at<br />

its zenith in the pre-conciliar Church,<br />

that would have seemed an utterly<br />

normal and appropriate thing for<br />

bishops to do — and, of course, in<br />

context, it was also quite a courageous<br />

stance.<br />

Decades later, the idea of bishops<br />

issuing orders to Catholic media<br />

about their editorial choices would<br />

be considerably more controversial.<br />

Since St. Brandsma’s day, most Catholic<br />

media outlets have won at least a<br />

measure of independence, and most<br />

bishops recognize the value of a free<br />

press. In many cases, Catholic media<br />

outlets are no longer owned directly<br />

by officialdom anyway, and thus are<br />

not subject to ecclesiastical control.<br />

Today, it’s easier to see more clearly<br />

that the role of Catholic media is to<br />

be close enough to the story to get it<br />

right yet far enough away to remain<br />

objective, with both ends of that equation<br />

being equally important.<br />

Reporters need to be close to the<br />

story in order to know what makes<br />

an institution tick, to be able to put<br />

breaking news in context, and to<br />

supply the proper perspective. The<br />

problem with much coverage of<br />

religious affairs in the secular press is<br />

precisely that it’s too far away. Stories<br />

are deprived of context and historical<br />

memory, so that it seems everything<br />

is always happening for the first time,<br />

and too much bogus or sloppy reporting<br />

makes it into circulation. (Anyone<br />

recall the “dogs in heaven” fiasco<br />

from 2014, for example?)<br />

Yet reporters also have to retain a<br />

certain critical distance from the<br />

story, because otherwise the risk is<br />

that stories will be distorted in order to<br />

serve a particular point of view. That’s<br />

the problem with much contemporary<br />

Catholic media, where many outlets<br />

have a clear ideological alignment in<br />

internal Catholic disputes, and their<br />

presentation of the news sometimes<br />

seems shaped to support those commitments.<br />

Maintaining critical distance<br />

requires self-restraint, because most<br />

Catholic journalists, by the nature<br />

of things, are well-informed about<br />

Church affairs, and it’s natural to<br />

develop personal views about rights<br />

and wrongs in the context of exploring<br />

the issues we cover. Yet in the end,<br />

the most valuable service any media<br />

outlet can provide isn’t opinion but<br />

analysis — not telling people what to<br />

think, but rather providing them with<br />

the tools to think intelligently whatever<br />

conclusion they may reach.<br />

To invoke a sports analogy, the<br />

Catholic media shouldn’t be a player<br />

in the game, pushing the Church to<br />

do one thing or another. We’re more<br />

akin to an umpire, calling balls and<br />

strikes but not having an investment<br />

in who wins or loses. Just as a baseball<br />

game would be tainted if an umpire<br />

slants his or her calls in favor of one<br />

team or another, journalists do their<br />

audiences a disservice when they slant<br />

their reports in favor of one position or<br />

another.<br />

That’s a terribly countercultural notion<br />

today, given that we live in an era<br />

of extreme political polarization and<br />

media fragmentation, meaning that<br />

the market pressure on news organizations<br />

generally is to serve the biases<br />

of some share of the audience. Yet just<br />

as St. Brandsma in his day resisted the<br />

lure of Nazi ideology, today Catholic<br />

journalists face the challenge of<br />

resisting a different sort of ideological<br />

regime, one which not-so-subtly seeks<br />

to turn reporting into an extension of<br />

politics by other means.<br />

In that sense, perhaps St. Brandsma<br />

actually would be an apt patron<br />

saint for contemporary journalists —<br />

even if, in all honesty, we probably<br />

shouldn’t be the ones campaigning<br />

for it.<br />

John L. Allen Jr. is the editor of Crux.<br />

<strong>June</strong> 3, <strong>2022</strong> • ANGELUS • 33