The Marine Biologist Issue 24

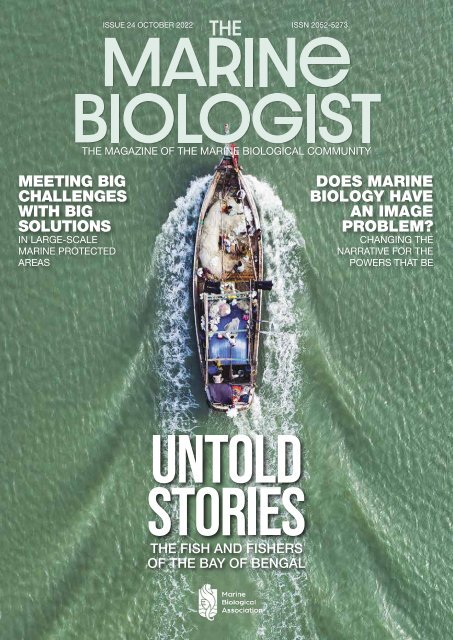

The Marine Biologist has had a redesign! With a fresh and professional new look, the magazine continues to bring you the latest marine life science, features, book reviews, and more from top names in the field. Our cover feature is the fascinating untold story of the fish and fishers of the Bay of Bengal by Alifa Haque. Dive in for an insightful read with beautiful images. In this edition we take a look at marine biology as a discipline, asking: does it have an image problem, and why does the marine biological community need a voice? Access to rewarding careers remains an issue and we hear from the Marine Biological Association’s Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion Committee about the barriers to accessing nature and marine science and how we can break them down. The magazine is just part of a great membership package from the Marine Biological Association (MBA). The MBA supports members on their journeys in marine biology, whether that is a high-flying career or simply a love of the sea. For our superb quarterly magazine and a host of other benefits join the MBA today.

The Marine Biologist has had a redesign! With a fresh and professional new look, the magazine continues to bring you the latest marine life science, features, book reviews, and more from top names in the field.

Our cover feature is the fascinating untold story of the fish and fishers of the Bay of Bengal by Alifa Haque. Dive in for an insightful read with beautiful images.

In this edition we take a look at marine biology as a discipline, asking: does it have an image problem, and why does the marine biological community need a voice? Access to rewarding careers remains an issue and we hear from the Marine Biological Association’s Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion Committee about the barriers to accessing nature and marine science and how we can break them down.

The magazine is just part of a great membership package from the Marine Biological Association (MBA). The MBA supports members on their journeys in marine biology, whether that is a high-flying career or simply a love of the sea. For our superb quarterly magazine and a host of other benefits join the MBA today.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

ISSUE <strong>24</strong> OCTOBER 2022 ISSN 2052-5273<br />

THE MAGAZINE OF THE MARINE BIOLOGICAL COMMUNITY<br />

MEETING BIG<br />

CHALLENGES<br />

WITH BIG<br />

SOLUTIONS<br />

IN LARGE-SCALE<br />

MARINE PROTECTED<br />

AREAS<br />

DOES MARINE<br />

BIOLOGY HAVE<br />

AN IMAGE<br />

PROBLEM?<br />

CHANGING THE<br />

NARRATIVE FOR THE<br />

POWERS THAT BE<br />

THE FISH AND FISHERS<br />

OF THE BAY OF BENGAL<br />

september 2022

september 2022<br />

MEETING BIG<br />

CHALLENGES<br />

WITH BIG<br />

SOLUTIONS<br />

IN LARGE-SCALE<br />

MARINE PROTECTED<br />

AREAS<br />

ISSUE <strong>24</strong> OCTOBER 2022 ISSN 2052-5273<br />

THE<br />

<strong>Marine</strong><br />

BiologiSt<br />

THE MAGAZINE OF THE MARINE BIOLOGICAL COMMUNITY<br />

DOES MARINE<br />

BIOLOGY HAVE<br />

AN IMAGE<br />

PROBLEM?<br />

CHANGING THE<br />

NARRATIVE FOR THE<br />

POWERS THAT BE<br />

contents<br />

18<br />

UNTOLD<br />

STORIES<br />

THE FISH AND FISHERS<br />

OF THE BAY OF BENGAL<br />

ON THE COVER:<br />

UNTOLD STORIES<br />

<strong>The</strong> fish and fishers<br />

of the Bay of Bengal<br />

REGULAR<br />

16<br />

03 EDITORIAL<br />

© Juliet Brodie<br />

06<br />

IN BRIEF<br />

04 IN BRIEF<br />

Current ocean issues and<br />

Association news.<br />

AN OCEAN OF<br />

SCIENCE<br />

06 STRUCTURAL<br />

COLOUR IN<br />

SEAWEEDS<br />

Dazzling displays are more<br />

than meets the eye. By<br />

Juliet Brodie.<br />

07 WHITHER<br />

COCCOLITHOPHORES<br />

IN A CHANGING<br />

OCEAN?<br />

Ocean acidification affects<br />

tiny algal cells’ capacity to<br />

calcify. By Colin Brownlee<br />

and Glen Wheeler.<br />

MARINE POLICY<br />

08 UN OCEANS 2022 –<br />

A POST-MEETING<br />

REFLECTION<br />

Matt Frost gives the<br />

insider’s view.<br />

FEATURES<br />

09 HAVE YOU ASKED THE<br />

FISHERS HOW TO<br />

SAFEGUARD THE FISH?<br />

Enchantment and ecosocial<br />

justice in the Bay of<br />

Bengal with Alifa Haque.<br />

14 MARINE BIOLOGY<br />

MATTERS IN THE<br />

CLIMATE AND<br />

BIODIVERSITY CRISIS<br />

Dan Laffoley outlines why<br />

marine biology is a key part of<br />

our global knowledge system.<br />

16 DOES MARINE BIOLOGY<br />

HAVE AN IMAGE<br />

PROBLEM?<br />

Matt Frost argues that<br />

the discipline of marine<br />

biology deserves greater<br />

recognition.<br />

18 MEETING BIG<br />

CHALLENGES WITH<br />

BIG SOLUTIONS<br />

Large-scale marine<br />

protected areas attract<br />

attention but Daniela Sturm<br />

asks what is behind the<br />

headlines?<br />

22 RESEARCH VESSEL<br />

AND INSTRUMENT<br />

MOORING TIPS<br />

Top tips for scientists and<br />

crew from an experienced<br />

sea captain.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Biologist</strong> is the Membership<br />

magazine of the <strong>Marine</strong> Biological Association<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Marine</strong> Biological Association<br />

<strong>The</strong> Laboratory<br />

Citadel Hill<br />

Plymouth<br />

PL1 2PB<br />

Editor<br />

Guy Baker<br />

editor@mba.ac.uk<br />

+44 (0)1752 426 331<br />

Executive Editor<br />

Matt Frost<br />

matf@mba.ac.uk<br />

+44 (0)1752 426 343<br />

@thembauk<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Guy Baker, Eliane Bastos, Matthew Bunce,<br />

Matt Frost, Kartik Shanker, Sophie Stafford.<br />

Membership<br />

Alex Street<br />

membership@mba.ac.uk<br />

+44 (0)1752 426 347<br />

www.mba.ac.uk/our-membership<br />

ISSN: 2052-5273<br />

www.mba.ac.uk/our-membership/our-magazine<br />

Views expressed in <strong>The</strong> <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Biologist</strong> are those<br />

of the authors and do not necessarily represent<br />

those of the <strong>Marine</strong> Biological Association.<br />

Copyright © the <strong>Marine</strong> Biological<br />

Association 2022.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Biologist</strong> is published by<br />

the <strong>Marine</strong> Biological Association,<br />

Registered Charity No. 1155893.<br />

We welcome your articles, letters and reviews,<br />

and we can advertise events. Please contact us<br />

for details, or see the magazine website at:<br />

www.mba.ac.uk/our-membership/our-magazine<br />

<strong>The</strong> Association permits single copying of individual<br />

articles for private study or research, irrespective<br />

of where the copying is done. Multiple copying<br />

of individual articles for teaching purposes is also<br />

permitted without specific permission. For copying<br />

or reproduction for any other purpose, written<br />

permission must be sought from the Association.<br />

Access to the magazine is available online; please<br />

see the Association’s website for further details.<br />

Published on behalf of the <strong>Marine</strong> Biological Association by:<br />

Century One Publishing<br />

Alban Row, 27–31 Verulam Road,<br />

St Albans,<br />

Herts,<br />

AL3 4DG<br />

T: 01727 893 894<br />

E: enquiries@centuryonepublishing.uk<br />

W: www.centuryonepublishing.uk<br />

Advertising Sales<br />

Jonathan Knight<br />

T 01727 739 182<br />

E jonathan@centuryonepublishing.uk<br />

Creative Director<br />

Peter Davies<br />

printed by<br />

Century One Publishing Ltd.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Biologist</strong> is printed on FSC ® mixed credit - Mixed<br />

source products are a blend of FSC 100%, Recycled and/or<br />

Controlled fibre. Certified by the Forest Stewardship Council ® .

34<br />

26<br />

THE VOICE OF<br />

MARINE BIOLOGY<br />

<strong>24</strong> A SPACE TO CONNECT<br />

Amplifying the voice of<br />

marine biology with Head<br />

of MBA Membership<br />

Jo Langston.<br />

26 OPENING THE DOOR<br />

TO MARINE SPACES<br />

AND SCIENCE<br />

Opportunities in rewarding<br />

careers such as marine<br />

science should be a universal<br />

right. By Joanna Harley.<br />

28 A FOUNDATION FOR<br />

SUCCESS<br />

Jason Birt introduces an<br />

alternative path into marine<br />

biology careers.<br />

30 THE YOUNG MARINE<br />

BIOLOGIST SUMMIT<br />

2022<br />

33 ADVANCING CAREERS<br />

MBA bursary winners’ reports.<br />

34 REVIEWS<br />

<strong>The</strong> best in marine biology<br />

books, movies, podcasts,<br />

and more.<br />

Plankton sampling for first year<br />

students off the north coast of<br />

Cornwall<br />

Protecting<br />

ecosystems is tied<br />

to social justice<br />

ARE YOU BEING<br />

HEARD?<br />

We are delighted to welcome new and regular<br />

readers to <strong>The</strong> <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Biologist</strong> magazine,<br />

improved and redesigned in the <strong>Marine</strong><br />

Biological Association’s new branding.<br />

<strong>The</strong> changes are just part of the Membership Team’s<br />

commitment to help support members’ careers and<br />

advance the wider profession.<br />

Why does the marine biological community need a<br />

voice? Ocean health is inseparable from human health and<br />

wellbeing but this is not reflected in resources directed to<br />

it (of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, SDG14 ‘Life<br />

Below Water’ received least funding), prompting Matt Frost<br />

to argue that the narrative around marine biology needs to<br />

change. Another reason is that as an authoritative community<br />

of experts, the Association is best placed to translate scientific<br />

knowledge into evidence for effective policy (see Dan<br />

Laffoley's article on page 14). One of the ways we are working<br />

to strengthen our voice is by facilitating communication and<br />

network-building among our community: Head of<br />

Membership Jo Langston sets the scene and introduces new<br />

ways for Association members to connect and be heard.<br />

Many voices simply aren’t heard because of exclusion<br />

or marginalization. In our initial article from the MBA’s EDI<br />

(Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion) Committee, Joanna<br />

Harley explores the barriers to accessing nature and marine<br />

science and how we can break them down.<br />

Large-scale marine protected areas offer hope for troubled<br />

waters in the form of recovery, regeneration, and wins<br />

for conservation and fishers. Or do they? Daniela Sturm<br />

examines this vast and uncertain world.<br />

Subsistence fishers in many parts of the world face<br />

inequitable distribution of shrinking resources as well as<br />

top-down regulation and poor working conditions. In our<br />

superb cover feature, Alifa Haque’s absorbing story reflects her<br />

enchantment with the fish and fishers of coastal Bangladesh,<br />

underlining that protecting ecosystems is tied to social justice.<br />

At the other end of the marine food web are coccolithophores:<br />

tiny algal cells cloaked in chalky plates. In their abundance<br />

they play a major role in cycling nutrients and drawing carbon<br />

out of the atmosphere. Professor Colin Brownlee and Dr Glen<br />

Wheeler are at the cutting-edge of cell biology and we are<br />

proud to present their insights into how these vital organisms<br />

will respond or adapt to an acidifying ocean.<br />

I hope this edition engages, informs, and inspires you. It<br />

is after all your platform and a reflection of our community.<br />

I look forward to views and ideas from you, the voice of<br />

marine biology.<br />

Guy Baker, EDITOR<br />

editor@mba.ac.uk

4<br />

i n b r i e f<br />

mysterious basking shark<br />

circles explained<br />

Rarely observed circling behaviour<br />

of basking sharks is described as<br />

courtship displays in a new study<br />

published in the Journal of Fish Biology.<br />

Circling formations have been<br />

documented on a few occasions over<br />

the past 40 years in the north-western<br />

Atlantic off Canada and the USA but<br />

never in the north-eastern Atlantic; in the<br />

absence of detailed investigation the<br />

purpose of the behaviour was unknown.<br />

Scientists from the UK and Ireland<br />

studied 19 circling groups using<br />

underwater cameras and aerial drones<br />

A basking shark<br />

courtship torus<br />

off County Clare, Ireland, from 2016 off to Ireland<br />

2021. <strong>The</strong> circling behaviour lasted many<br />

hours and comprised between six and<br />

23 non-feeding sharks swimming slowly<br />

at the surface, with others below them<br />

deeper down, in a three-dimensional ring<br />

structure the researchers termed a ‘torus’.<br />

Within a torus, roughly equal numbers<br />

of mature female and male sharks more<br />

than 7 m in total length interacted<br />

through close-following behaviours,<br />

fin-fin and fin-body contacts, rolling to<br />

expose ventral surfaces to following<br />

sharks, and breaching. Interestingly,<br />

female body colouration was paler<br />

than that of males, similar to colour<br />

changes seen during courtship and<br />

mating in other shark species. Individuals<br />

associated with most other torus<br />

members rapidly (within minutes),<br />

indicating that toroidal behaviours<br />

facilitated multiple interactions, like slowmotion<br />

‘speed dating’. <strong>The</strong> observations<br />

explain a courtship function for toruses,<br />

A basking shark courtship<br />

torus off Ireland.<br />

the study concludes.<br />

<strong>The</strong> study highlights north-eastern<br />

Atlantic coastal waters as important<br />

habitat for courtship reproductive<br />

behaviour of endangered basking<br />

sharks, which may require conservation<br />

measures to reduce potential risks from<br />

disturbance by marine traffic.<br />

David W. Sims<br />

©IRISH BASKING SHARK GROUP.<br />

Don’t be shy;<br />

share your<br />

expertise<br />

Would you like to share your<br />

research or professional expertise<br />

with MBA members and the wider<br />

marine biological community?<br />

We run a programme of talks,<br />

courses, and events on hot topics<br />

in marine biology and we are<br />

encouraging applications from<br />

research scientists and other experts<br />

in their field to share their insights<br />

and expertise. If you would like to be<br />

considered to speak or present at an<br />

MBA event, please fill in the form on<br />

our website. You will need to send<br />

a link or upload a video clip of you<br />

speaking for your application to be<br />

considered.<br />

To apply, please visit:<br />

bit.ly/MBAspeakers<br />

A diamond jubilee ‘down-under’<br />

A little after the MBA was<br />

founded in 1884, a group of<br />

43 Australian marine scientists<br />

got together, in August 1962,<br />

to discuss the formation of a<br />

professional association. This meeting<br />

established the Australian <strong>Marine</strong> Science<br />

Association (AMSA—see https://www.<br />

amsa.asn.au). <strong>The</strong> fledgling society held<br />

its inaugural meeting in May 1963, by<br />

which time there were 130 members.<br />

Amongst those founding members<br />

were Dr (later Sir) Frederick Russell, then<br />

Director of the MBA Plymouth Laboratory<br />

and Dr John Gulland of the Fisheries<br />

Laboratory, Lowestoft (later of FAO).<br />

As we begin our Diamond Jubilee year,<br />

the membership numbers over 800 and<br />

the 2022 annual conference in Cairns<br />

was attended by over 650 delegates. <strong>The</strong><br />

2023 meeting that bookends the Jubilee<br />

year will be in July on the Gold Coast, in<br />

Yugambeh Country, Queensland.<br />

www.amsa2023.amsa.asn.au).<br />

No organization that<br />

survives into a seventh<br />

decade does so by standing<br />

still, and AMSA is continually<br />

reviewing the role of marine science<br />

in the contemporary world and asking<br />

how it can best serve the marine science<br />

community. Joining the professional<br />

and student membership classes is a<br />

new category of Associate Member for<br />

individuals who are not professional<br />

marine scientists but have an interest<br />

in marine science and the ocean realm.<br />

This will allow indigenous sea rangers,<br />

eco-tour guides, and amateur/citizen<br />

scientists to formally engage with<br />

AMSA. Another recent initiative<br />

revitalized our publications and<br />

communications strategies to ensure that<br />

marine science continues to reach the<br />

widest possible audience.<br />

Chris Frid<br />

october 2022<br />

www.mba.ac.uk

i n b r i e f 5<br />

Mentorship matters<br />

Are you seeking guidance from<br />

a professional to kick-start your<br />

career? Maybe you could offer that<br />

guidance or have the drive to inspire<br />

others. <strong>Marine</strong> Biological Association<br />

Members* are eligible to join our<br />

mentoring scheme which matches<br />

mentors with mentees.<br />

Discover your inner mentor<br />

<strong>The</strong> role of a mentor is to share with<br />

their mentee information<br />

about their own career,<br />

motivation, and work/life<br />

balance.<br />

Are you wanting to<br />

develop yourself and<br />

your career?<br />

<strong>The</strong> mentee articulates<br />

their goals and<br />

objectives through a<br />

<strong>Marine</strong> sediments and coastal<br />

habitats such as seagrass,<br />

kelp beds, and salt marsh<br />

are acknowledged for their carbon<br />

sequestration properties, although little<br />

is known about the amount of carbon<br />

stored in each of these habitats.<br />

Blue Carbon Mapping is a pioneering<br />

project from the Scottish Association<br />

of <strong>Marine</strong> Science (SAMS) and funded<br />

by WWF-UK alongside the RSPB and<br />

Wildlife Trusts to map the amount<br />

of blue carbon stored along the UK<br />

coastline. Professor Michael Burrows<br />

of SAMS stated, ‘<strong>The</strong> project will<br />

provide baseline information for key<br />

policy decisions’. Indeed, quantifying<br />

and mapping blue carbon will inform<br />

marine planning decisions, help us<br />

to understand the impacts of human<br />

activities, and could influence the<br />

government to protect much more of<br />

the UK’s coastal environment towards<br />

its goal of protecting 30 per cent of UK<br />

seas by 2030.<br />

<strong>The</strong> project builds upon a pilot study<br />

in the North Sea which showed that<br />

the carbon stored in the English sector<br />

of the North Sea amounts to nearly<br />

20 per cent of that in UK forests and<br />

woodlands.<br />

development plan and will need<br />

to be motivated and ready to lead<br />

mentorship sessions.<br />

Sessions take place online within<br />

the MBA Members’ Portal. Together,<br />

mentor and mentee develop an<br />

action plan with goals and objectives.<br />

<strong>The</strong> scheme provides a space for<br />

discussion and advice and supports<br />

mentor and mentee to establish a<br />

professional relationship.<br />

Scan now to discover<br />

your mentoring<br />

community group.<br />

* Mentoring opportunities<br />

are open to all membership<br />

categories except Young<br />

<strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Biologist</strong>.<br />

Map of blue carbon<br />

stores to help achieve 30<br />

by 30 commitment<br />

When the final report is released in<br />

summer 2023, the UK will be the first<br />

country with such a resource, which, it is<br />

hoped, will pave the way in prioritizing<br />

conservation areas based on protecting<br />

blue carbon.<br />

Kyra Walton<br />

Kiribati fisherman.<br />

Small is beautiful<br />

when it comes to<br />

sustainable fisheries<br />

and boosted<br />

economies<br />

Seafood is a staple source of protein in<br />

the diets of billions of people. Fisheries<br />

and aquaculture provide the main<br />

source of animal protein to 17 per cent<br />

of the world’s population, with over 3<br />

billion people, largely in developing<br />

countries, depending on the ocean to<br />

make a living.<br />

Demand for seafood is set to rise<br />

alongside increasing populations and<br />

increasing levels of consumption. Smallscale<br />

fisheries have huge potential to<br />

not only feed populations, but also<br />

provide direct income to many people.<br />

Low levels of bycatch and higher levels<br />

of consumable fish make these fisheries<br />

more efficient and less environmentally<br />

damaging than industrial fleets.<br />

However, some practices may have to<br />

be reformed to strengthen operations.<br />

With the UN General Assembly<br />

declaring 2022 the International Year of<br />

Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture, the<br />

UN is supporting small-scale fisheries<br />

in a bid to improve food security<br />

and eradicate poverty in developing<br />

countries. Measures include local<br />

governments directing more subsidies<br />

and funding to small-scale fisheries<br />

instead of large-scale fleets, avoiding<br />

overfishing and environmentally<br />

destructive techniques. <strong>The</strong> introduction<br />

of cold storage and processing<br />

equipment—for example, for smoking<br />

or drying—could massively reduce<br />

the number of fish-production losses<br />

experienced by small-scale fisheries.<br />

Capturing and passing on artisanal<br />

fishers’ local knowledge to other smallscale<br />

fisheries in the region could also<br />

make local fleets much more efficient<br />

and environmentally friendly.<br />

Kyra Walton<br />

©DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND TRADE, CC BY 2.0 , VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS<br />

www.mba.ac.uk<br />

october 2022

6<br />

a n o c e a n o f s c i e n c e<br />

structural colour<br />

in seaweeds: more than<br />

meets the eye<br />

Discovering seaweeds on the shore that<br />

sparkle and twinkle shades of blue, mauve,<br />

turquoise, green, and pink in sunlight is an<br />

awe-inspiring experience. Structural colour,<br />

widespread in the marine environment, has barely<br />

been studied in red, green, and brown seaweeds until<br />

now. Our work indicates that this phenomenon is more<br />

common in seaweeds than previously thought, both<br />

geographically and in evolutionary development.<br />

By removing blue wavelengths of light, we suspect<br />

that structural colour may provide protection from the<br />

harmful effects of UV radiation. However, it could be a<br />

way of moving light to where it is needed, or providing<br />

defence against predators. Colour production includes<br />

multi-layered structures (reds), iridescent bodies (reds<br />

and browns), and microfibril arrays (greens) which<br />

also occur in the charophytes (freshwater green algae)<br />

and land plants. Such observations raise intriguing<br />

evolutionary questions across the tree of life for these<br />

remarkable photosynthesizers. Professor Juliet Brodie<br />

(j.brodie@nhm.ac.uk) Merit Researcher, Department of<br />

Life Sciences at the Natural History Museum.<br />

• Professor Juliet Brodie (j.brodie@nhm.ac.uk)<br />

Merit Researcher, Department of Life Sciences at<br />

the Natural HistoryMuseum.<br />

© Juliet Brodie<br />

This work is part of ‘BEEP’ (Bio-inspired<br />

and Bionic materials for Enhanced<br />

Photosynthesis), an interdisciplinary<br />

research training network funded by<br />

the EU Horizon 2020 programme.<br />

https://www.ch.cam.ac.uk/beep/home<br />

october 2022<br />

www.mba.ac.uk

a n o c e a n o f s c i e n c e 7<br />

whither coccolithophores<br />

in a changing<br />

ocean?<br />

Colin Brownlee and Glen Wheeler look at the<br />

implications of ‘the other CO 2<br />

problem’.<br />

© MBA<br />

Figure 1: Scanning electron micrograph of the coccolithophore<br />

Coccolithus braarudii, showing external calcite coccoliths that are<br />

produced inside the cell and secreted to the cell surface.<br />

Global temperature increases in response to<br />

anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are<br />

predicted to have multiple consequences,<br />

including changes in ocean currents, polar ice<br />

cover, nutrient availability, and surface ocean oxygen levels.<br />

<strong>The</strong> consequences of such changes are predicted to include<br />

phytoplankton community regime shifts, with consequent<br />

knock-on effects on the overall structure of marine ecosystems.<br />

Increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) levels also have<br />

more direct impacts on ocean chemistry. As carbon dioxide<br />

dissolves in the ocean it forms carbonic acid, which itself<br />

2-<br />

dissociates into bicarbonate (HCO 3-<br />

), carbonate (CO 3<br />

) and<br />

protons (H + ):<br />

CO 2<br />

+ H 2<br />

O ↔ H 2<br />

CO 3<br />

↔ HCO 3<br />

-<br />

+ CO 3<br />

2-<br />

+ H +<br />

<strong>The</strong> concentration of H + (acidity) in the surface ocean<br />

therefore increases as atmospheric CO 2<br />

increases. Put another<br />

way, the pH of the oceans is steadily declining during the<br />

process of ocean acidification. It is important to understand<br />

that the oceans are unlikely to become truly acid (i.e. pH below<br />

7.0). <strong>The</strong> mean pH of the ocean surface is around 8.2 and it has<br />

fallen by about 0.1 pH unit since the mid-20th century. While<br />

model predictions vary, it is likely to fall further to around 7.8 or<br />

lower by the end of the 21st century. However, since the acidity<br />

of the ocean surface is not uniform, certain regions, such as<br />

coastal and polar seas, are likely to see larger falls in pH over<br />

this timescale.<br />

While elevated carbon dioxide levels may actually help<br />

certain phytoplankton species to photosynthesize better, it<br />

is important to distinguish the effects of increased carbon<br />

dioxide and increased acidity. Greater H + concentrations<br />

are likely to have increasingly negative impacts on marine<br />

organisms, particularly those that produce calcium carbonate,<br />

such as many molluscs, corals, foraminifera and the calcifying<br />

coccolithophore phytoplankton. Indeed, negative impacts of<br />

increased ocean acidity have already been observed in species<br />

such as pteropods that produce a more soluble form of calcium<br />

carbonate (aragonite) in their shells which is more susceptible<br />

to dissolution. Similarly, corals that produce aragonite skeletons<br />

are likely to be more susceptible to increasing acidity.<br />

What about the coccolithophores, which produce much<br />

of the ocean’s calcium carbonate? Unlike other calcifying<br />

organisms, the unicellular coccolithophores produce calcium<br />

carbonate in the form of crystalline calcite plates (coccoliths)<br />

inside their cells, from where the coccoliths are secreted onto<br />

the cells’ surface (see Fig. 1). One might then assume that the<br />

calcification process would be protected from the effects of<br />

external acidification. Moreover, calcite is a less soluble form<br />

of calcium carbonate, so is less likely to dissolve in more acidic<br />

conditions, and protection from dissolution may also be given<br />

by an organic layer. Nevertheless, while experimental results<br />

vary between species, the general consensus is that increased<br />

acidity is likely to have a negative impact on coccolithophore<br />

calcification. In order to understand why this may be, it is<br />

important to better understand the mechanism of calcification.<br />

Coccolithophores take up bicarbonate, where it combines with<br />

calcium ions inside a special vesicle to form calcite. A major<br />

by-product of this reaction is H + , which must be removed to<br />

enable the calcification reaction to proceed. It was recently<br />

shown that coccolithophores utilize a special mechanism to<br />

bring this about, whereby ion channels that selectively allow<br />

H + to diffuse out of the cell can open and close depending on<br />

the cell’s internal pH.<br />

This mechanism works well at normal seawater pH but it is<br />

ineffective and shuts down at lower seawater pH that prevents<br />

diffusion of H + out of the cell, and the ability<br />

www.mba.ac.uk<br />

october 2022

Figure 2. Internal calcification is a pH-dependent<br />

process. Protons produced at the site of calcification<br />

are removed from the cell through H + channels in<br />

the cell membrane. However, this process becomes<br />

compromised as seawater acidity increases.<br />

to calcify becomes compromised (Fig. 2).<br />

Coccolithophores that produce heavily calcified<br />

coccoliths were shown to be more affected by this.<br />

Mechanistic understanding of this kind will<br />

hopefully allow researchers to better understand<br />

the impacts of changing ocean chemistry on<br />

calcification in a wider range of coccolithophores—<br />

essential if we are to predict how this planetaryscale<br />

major biogeochemical process is likely to be<br />

impacted in the future.<br />

• Professor Colin Brownlee (cbr@MBA.ac.uk), Lankester<br />

Research Fellow<br />

• Dr Glen Wheeler (glw@MBA.ac.uk), MBA Senior<br />

Research Fellow<br />

Further reading<br />

Taylor A.R., Brownlee C. and Wheeler G.L. 2017. Coccolithophore cell biology: Chalking up progress. Annual Review of <strong>Marine</strong> Science<br />

9: 283-310. https://doi/10.1146/annurev-marine-12<strong>24</strong>1403032.<br />

Kottmeier D.M., Chrachri A, Langer G., Helliwell K.E., Wheeler G.L. and Brownlee C. 2022. Reduced H + channel activity disrupts pH<br />

homeostasis and calcification in coccolithophores at low ocean pH. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA:<br />

119, e2118009119 https://doi.org/10/1073/pnas.211809119.<br />

8<br />

m a r i n e p o l i c y<br />

un oceans 2022—<br />

a post-meeting<br />

reflection<br />

<strong>The</strong> Second UN Ocean Conference,<br />

co-hosted by the Governments of<br />

Kenya and Portugal, was convened in<br />

Lisbon, Portugal, from 27 June to 1 July<br />

with more than 6,000 participants, including<br />

many Heads of State and Government in<br />

attendance. <strong>The</strong> theme was ‘Scaling up ocean<br />

action based on science and innovation for<br />

the implementation of SDG 14: Stocktaking,<br />

partnerships and solutions’ and there was a<br />

renewed sense of urgency as world leaders<br />

recognized that up to this point there has been<br />

a ‘collective failure to achieve Ocean related<br />

targets’ (7 SDG targets have already been<br />

missed). This fact along with admission that<br />

SDG14 is the least funded of all the SDGs, only accounting for<br />

about 1.6 per cent of the Overseas Development Aid (ODA)<br />

and 1.7 per cent of global research funding was, if anyone<br />

needed one, a sobering reminder of the challenges ahead.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re were, as expected, a raft of pledges, calls to arms,<br />

and proposed actions—particularly as part of the Lisbon<br />

declaration—but were there genuine grounds for optimism<br />

that things can be different in future? One important element<br />

was the focus on the need for innovative financing solutions<br />

including a concerted focus on global philanthropy. Utilising<br />

the private sector will be important but this should not detract<br />

from the need for G7 countries to ‘step up’ when it comes<br />

to action and associated funding. <strong>The</strong> marine community<br />

must also be better in articulating links between SDG14 and<br />

wider issues in order to encourage investment. Emphasising<br />

the importance of marine science and<br />

environmental action to support solutions for<br />

SDG targets for poverty, hunger, climate, clean<br />

water, and others will be key to unlocking both<br />

private and public funding, but is a message<br />

that the marine community has not always been<br />

good at conveying (See ‘Does <strong>Marine</strong> Biology<br />

have an image problem?’).<br />

As for the MBA, as an official UN-accredited<br />

participant, we were able to participate firsthand<br />

in meetings, observe and contribute<br />

to discussions, and network with many other<br />

delegates. <strong>The</strong> MBA’s voluntary commitment:<br />

‘World Association of <strong>Marine</strong> Stations:<br />

Mobilising global capacity and facilitating<br />

networking and capacity building’, was one of 700 new<br />

commitments made by organizations. <strong>The</strong>se ‘concrete and<br />

realistic’ pledges will be crucial in order to underpin the<br />

broader outcomes agreed at the meeting and ensure the next<br />

one starts on a more positive note.<br />

• Matt Frost (matfr@mba.ac.uk), Head of Policy and<br />

Engagement/MBA Deputy Director<br />

october 2022<br />

www.mba.ac.uk

f e a t u r e 9<br />

have you asked<br />

the fishers how to<br />

safeguard<br />

the fish?<br />

<strong>The</strong> untold stories of the enchanting fish and fishers of Bangladesh’s Bay of Bengal, by Alifa Haque.<br />

Bangladesh’s Bay of Bengal<br />

In the north of the Bay of Bengal—the biggest bay<br />

in the world, is Bangladesh. It is a coastal nation<br />

with an extremely biodiverse 710-kilometre<br />

coastline and home to the longest (125km)<br />

unbroken sea beach in the world: Cox’s Bazar.<br />

Rivers, floodplains, wetlands, mudflats, rocky<br />

beaches, coral reefs, and seagrass beds make<br />

up the country’s coastal and marine habitats.<br />

In the west lies the Sundarbans Reserve Forest,<br />

further east is the freshwater and nutrient-rich<br />

Meghna deltaic plain, and in the east is the<br />

Chittagong Coastal Plain, with rock and reef and<br />

less freshwater influence. Further offshore are<br />

unexplored deep oceanic waters, and deepwater<br />

continental shelf habitats.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Sundarbans Reserve Forest is located in<br />

Above: Alifa Haque<br />

awaits the day’s<br />

catch, Bay of Bengal,<br />

Bangladesh.<br />

the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta, where the<br />

Ganges, Padma, Brahmaputra, and Meghna<br />

rivers converge. At 10,000 km 2 , it is the<br />

biggest continuous halophytic mangrove<br />

forest in the world, with 62 per cent of its<br />

area located in south-western Bangladesh<br />

and the rest in India. Its intricate ecosystem,<br />

combining freshwater, estuarine, and marine<br />

waters, makes it a unique home for wildlife:<br />

fish, sea snakes, whales, sharks, rays, dolphins,<br />

corals, marine turtles, seagrasses, and a huge<br />

diversity of invertebrates including crabs,<br />

shrimps, worms, and molluscs are<br />

found here.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se coastal ecosystems provide the bread<br />

and butter for the fisherfolk and, in turn, the<br />

economy of Bangladesh.<br />

www.mba.ac.uk<br />

october 2022

10<br />

f e a t u r e<br />

<strong>The</strong> coastal and marine fisheries<br />

of Bangladesh<br />

Bangladesh’s coastal and marine fisheries are<br />

complex and heterogeneous. <strong>The</strong> artisanal<br />

and industrial sectors are clearly distinguished<br />

from one another. <strong>The</strong>re are currently nearly<br />

68,000 artisanal fishing vessels operating in<br />

Bangladesh; in comparison, there were only<br />

5,783 fishing vessels registered in the UK in<br />

2021. About 3 million hilsa (see below) fishers<br />

depend on these fisheries, and artisanal fisheries<br />

support 12 million people in Bangladesh. <strong>Marine</strong><br />

fisheries are one of the most crucial sectors<br />

in ensuring food security and livelihood for<br />

millions of Bangladeshis. Between 2015 and<br />

2016, marine fisheries production was 0.626<br />

million MT contributing 16 per cent of the total<br />

fish production of Bangladesh, with a growth<br />

rate of nearly 4.5 per cent. A significant amount<br />

of unreported catch is made up of subsistence,<br />

discarded bycatch, and underreported<br />

commercial catch.<br />

Artisanal fisheries (using powered or<br />

unpowered fishing vessels) use gears including<br />

gillnets and modified gillnets, set-bag nets,<br />

longlines, hooks, trawl nets, seine nets, bambooset<br />

nets, and trammel nets. <strong>The</strong> hilsa shad<br />

(a pelagic, clupeid fish, the national fish of<br />

Bangladesh and formerly abundant in the Bay<br />

of Bengal) and Bombay duck are single species<br />

contributors of the artisanal marine capture.<br />

However, there is bycatch of sharks and rays<br />

during the fishing season (Fig.1). When all<br />

artisanal fisheries are combined, they account<br />

for 80 per cent of the shark and ray bycatch in<br />

Bangladesh. However, one traditional practice<br />

of targeting rays still persists within the artisanal<br />

practices. In Bangladesh, the tradition of target<br />

ray fishing dates back decades, and fishing<br />

techniques have been passed down through<br />

generations. During fishing season, 10 to 12<br />

fishers go to sea, for 5 to 7 days. Fish are mostly<br />

caught down to 40 m, although deeper areas are<br />

also frequented by artisanal fishers.<br />

Figure 1 (above).<br />

Bycatch of sharks<br />

and rays.<br />

Figure 2 a (right).<br />

<strong>The</strong> author holding a<br />

large pectoral fin. <strong>The</strong><br />

price of four large dried<br />

fins—two pectorals, a<br />

first dorsal, and a lower<br />

caudal fin—measuring 51<br />

to 66 cm can be as high<br />

as $356 and fin sets sell<br />

for even more on the<br />

international market. Due<br />

to the size of the fins and<br />

commercial demand,<br />

hammerhead sharks,<br />

giant carcharhinids, and<br />

rhino rays are the most<br />

coveted species by<br />

traders.<br />

Figure 2 b (below).<br />

Shark fins and meat<br />

drying on a rack.<br />

© FAYED MASUD KHAN<br />

Species and trade: sharks and rays<br />

Unsustainable fishing, fuelled by a growing<br />

demand for fins and meat (see Fig. 2), has led to<br />

an 80 per cent or more decline of elasmobranchs<br />

in some areas of the world. About 37per cent of<br />

all elasmobranch species are now threatened<br />

with extinction, according to the International<br />

Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red<br />

List of Threatened Species. Only a handful<br />

of nations—including the USA and Australia—<br />

manage elasmobranch fisheries responsibly and<br />

can be considered exceptions to the norm. Little<br />

is known about species-specific management.<br />

Until recently, Bangladesh has had no speciesspecific<br />

data on sharks and rays, and we were<br />

unaware of the historical fishing pressure. Our<br />

study spanning the last 6 years found that more<br />

than 110 shark and ray species were reported<br />

from Bangladesh, and they are all susceptible to<br />

october 2022<br />

www.mba.ac.uk

f e a t u r e 11<br />

excessive fishing pressure (Fig. 3). More than 90<br />

species of sharks and rays are protected under<br />

the newly amended national law, reflecting<br />

an umbrella catch and trade ban on almost all<br />

species that are present and frequently entangled<br />

in fishing gear. An umbrella embargo on trade is<br />

advocated for and implemented in many areas in<br />

the global south, but success is limited.<br />

Although considered non-commercial, on<br />

average, 4,588 MT of sharks and rays were<br />

bycaught and landed between 2005 and 2018.<br />

In 2015–16 alone, a very conservative survey<br />

revealed 622 MT of sharks and rays were caught<br />

by industrial trawlers, 1,920 MT by gill nets, 205<br />

MT by set-bag nets, 1,875 MT by long lines and<br />

4,000 MT by other gears which were not listed.<br />

Figure 3 a (top). <strong>The</strong><br />

sharpnose guitarfish is a<br />

protected species under<br />

Bangladesh law.<br />

Figure 3 b (above).<br />

Largetooth sawfish<br />

rostrum.<br />

Fishers<br />

Although millions of fishers depend on marine<br />

fisheries and contribute greatly to the GDP, they<br />

are one of the most marginalized communities,<br />

prone to vulnerabilities such as financial<br />

marginalization, natural calamities, no safeguards<br />

at sea, and lack of education and healthcare. Of<br />

late, they are also blighted by low catches at sea.<br />

‘In the 1990s, we had to come back to shore<br />

daily after a fishing trip as we caught more<br />

than 2,000 rays in less than 7 days and had no<br />

storage capacity. Twenty years ago, a seven-day<br />

fishing trip was enough for an entire month’s<br />

subsistence for fishers on the boat if we were<br />

lucky. Now there are days we don’t even catch a<br />

single individual in a week’, said one fisher.<br />

Another fisher mentioned species being lost<br />

before they could be recorded and researched<br />

by scientists, such as one Critically Endangered<br />

wedgefish. He said, ‘Until the 2000s, a species<br />

of rhino ray with flower-like spots was caught<br />

quite frequently, but we haven’t seen it in the<br />

past decade.’ He was talking about a wedgefish<br />

species we haven’t recorded in the past 7 years,<br />

even after continuous efforts in landing-site<br />

data collection.<br />

Fishers are incredibly trusting and hardworking<br />

people. <strong>The</strong>y are usually ready to<br />

extend help and have been interviewed by many<br />

researchers and NGOs for data collection or<br />

are listed as so-called ‘beneficiaries’, but there<br />

seems to have been some exploitation there<br />

too. Fishers do not know how the data will be<br />

used and what impact the study may have on<br />

their fishing practices. This was apparent in<br />

many conversations that we had over the years.<br />

Awareness-raising is limited to posters, banners,<br />

and top-down meetings, which inherently do not<br />

allow true collaboration with fishers. A sudden<br />

© OLIVER DEPPERT/ SAVE OUR SEAS FOUNDATION<br />

www.mba.ac.uk<br />

october 2022

12<br />

f e a t u r e<br />

amendment of a law protecting new species<br />

without consulting and facilitating the fishers’<br />

adherence to the regulations will only criminalize<br />

them overnight.<br />

Some fishers mentioned, ‘Researchers collect<br />

their information and leave. Nothing changes<br />

for us. Officials come, and sometimes we oblige,<br />

fearing punishment for something we don’t<br />

know what to do about, a regulation we don’t<br />

know how to adhere to or why.’<br />

Some fishers have lost faith in the system and<br />

believe policy-makers do not consider them or<br />

their problems: ‘Nobody cares about us. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

bans only make our lives harder and no one ever<br />

asks what we need to maintain our livelihoods.<br />

<strong>The</strong> minimal compensations are not enough and<br />

do not even reach every one of us.’<br />

Due to debt-driven fishing tactics, coastal fishers<br />

are very likely to live in poverty all their lives. Most<br />

of them lack boats or nets, alternative sources of<br />

income, access to effective marketplaces, and<br />

tools necessary to follow the rules.<br />

© OLIVER DEPPERT/ SAVE OUR SEAS FOUNDATION<br />

Conservation of fish and fishers<br />

<strong>The</strong> future of sharks and rays is sandwiched<br />

between two issues: protecting marine species<br />

in their habitats, and safeguarding the wellbeing<br />

of fishers who depend on the same fisheries<br />

that bycatch sharks and rays. <strong>The</strong> dilemma<br />

is worsened by habitat degradation, climate<br />

change, and pollution in nearshore areas that<br />

these species prefer.<br />

But bycatch and trade mitigation in a developing<br />

country is easier said than done. For starters,<br />

tackling bycatch requires a lot of technical facilities,<br />

gear modification, and research to drive decisions.<br />

Most importantly, a long-term investment towards<br />

fishers is needed so they adhere to regulations;<br />

if their lost catch is compensated, then the whole<br />

process is incentivized. This should also be aided<br />

by social and psychological understanding of<br />

fishing communities regarding their adoption of<br />

these new means.<br />

Moreover, trade is exceptionally complicated,<br />

involving many actors with different motivations<br />

and varied access to benefits. All these play an<br />

important role in the trading process, which is<br />

notoriously diverse in different geographic and<br />

cultural contexts.<br />

This multifaceted issue dooms any ‘one size fits<br />

all’ conservation management measure to failure.<br />

A more nuanced approach is needed, where<br />

management plans are co-designed with fishers.<br />

In trying to determine bycatch mitigation<br />

initiatives, I learned of the fishers’ vulnerabilities,<br />

which hindered them from making informed<br />

conservation decisions. <strong>The</strong>re is limited political<br />

or public interest in establishing better markets<br />

that run sustainably and guarantee an equitable<br />

opportunity for all fishers.<br />

A fair and practical first step towards<br />

sustainable fishing and species protection will<br />

involve distribution of revenues from sustainable<br />

practices to fishers, thus decreasing poverty<br />

Figure 4. Solutions lie in<br />

traditional practices and<br />

creating a market where<br />

fishers have an equal<br />

opportunity to earn from<br />

the sustainable catch.<br />

and ensuring better income. For instance, the<br />

fishery for hilsa is Bangladesh’s most significant<br />

single-species coastal fishery, providing<br />

livelihoods for 500,000 Bangladeshi nationals.<br />

<strong>The</strong> government has invested highly in the<br />

sustainable extraction of hilsa. <strong>The</strong> measures aim<br />

to reduce exploitation rates and include limits on<br />

exploitation of juvenile fish through a seasonal<br />

prohibition on fishing in sanctuary regions<br />

and seasonal restrictions elsewhere, fishing<br />

gear limits, and specific controls for fishing<br />

vessels. Fishing for hilsa is also prohibited at<br />

particular times of the year to preserve spawning<br />

individuals. Payments for ecosystem services<br />

were established to enforce such restrictions.<br />

One kilogram of hilsa can be sold for as much<br />

as US$30–35 and upwards for larger sizes in the<br />

cosmopolitan markets. In a good season, one<br />

boat owner can earn up to US$30,000, whereas<br />

the fisher employed by the boat owners, working<br />

relentlessly in dangerous sea conditions, earns<br />

as low as US$30–100 a month. We propose that<br />

the huge revenues earned from the hilsa should<br />

return to the fishers equally, to improve their<br />

livelihoods.<br />

It is crucial to understand how fishers perceive<br />

various species to design targeted conservation<br />

actions. It is also essential to understand the<br />

changing relationship of people, including<br />

fishers, with the fish. <strong>The</strong> point here is that there<br />

is a connection between fish and fishers. For<br />

instance, fishers identify hilsa as a blessing of the<br />

october 2022<br />

www.mba.ac.uk

f e a t u r e 13<br />

sea and the primary source of their livelihoods.<br />

<strong>The</strong>n there is the belief that manta rays breach<br />

as a warning of impending bad weather. Some<br />

fishers also believe that the sawfish is vital to the<br />

sea as it maintains ecological balance and also<br />

cures cancer. <strong>The</strong>se beliefs help us get to know<br />

the relationship between the fish and fisher,<br />

understand how they value a particular species,<br />

and plan accordingly. Fishers’ understanding of<br />

the ecosystem services of a species is fascinating<br />

and can be crucial in how they will contribute to<br />

their conservation.<br />

We conducted a study where we interviewed<br />

more than 1,000 fishers and ran over 30<br />

workshops to understand the barriers to<br />

releasing a sawfish alive, or what would be<br />

acceptable bycatch mitigation strategies.<br />

While most would assume loss of income,<br />

we found several other reasons that impact a<br />

fisher’s decision-making process. For instance,<br />

many fishers do not have the authority (in the<br />

organogram of the men occupying the boat)<br />

to release such a catch and feared they would<br />

lose their jobs if they did so. Fishers mentioned<br />

that if they released such a catch, then fishers<br />

from neighbouring countries would catch them<br />

anyway, and why should Bangladeshis suffer<br />

the loss when the government does not stop<br />

foreign fishers from coming into their waters.<br />

When we asked what facilities and incentives<br />

they need to release a sawfish alive, to our<br />

surprise, they spoke about creating equity<br />

It is crucial<br />

to understand<br />

how fishers<br />

perceive<br />

various species<br />

to design<br />

targeted<br />

conservation<br />

actions.<br />

in the decision-making process; they talked<br />

about initiatives that mitigate danger at sea;<br />

for example, communication devices or better<br />

working practices. Fishers further said they need<br />

to be consulted, respected and not marginalized<br />

by regulations. In short, they want to be<br />

empowered.<br />

Many older fishers are as troubled as<br />

conservationists by decreasing catches and the<br />

loss of many charismatic species. It made me<br />

understand that it is not a competition between<br />

policy-makers and fishers to save these species.<br />

Instead, it is a case of striving for a common goal<br />

in collaboration.<br />

A number of fishers considered that individual<br />

action-based monetary incentives could be<br />

unsustainable, as the limited reimbursement<br />

does not meaningfully help the fishers.<br />

Furthermore, when the project ends, the<br />

incentive ends without leaving a legacy for the<br />

sustainable practice to be continued. Instead, a<br />

solution embedded in the traditional practices<br />

and creating a balanced market, where fishers<br />

have an equal opportunity to earn from the<br />

sustainable catch, is far more practical for the<br />

long-term benefit of both the fish and the fisher.<br />

Solutions need to be culturally appropriate and<br />

co-designed. Nevertheless, global and national<br />

strategies to protect small-scale fisheries and<br />

marine conservation vary significantly.<br />

Take-away messages<br />

More investment in research is urgently needed<br />

to design a sustainable management plan for the<br />

elasmobranchs of Bangladesh.<br />

Sustainable conservation must be founded<br />

on sound socio-ecological policies that protect<br />

fish and fishers. A paradigm shift must take<br />

place in marine conservation laws and policies<br />

formulated in powerful institutions far from<br />

shore. Pre-policy consultations with fishers are<br />

crucial to determining the level of acceptability<br />

and viability of laws and policies being drafted.<br />

This may seem challenging, time- and resourceintensive,<br />

but it will be beneficial, as inefficient<br />

policies will have more costly and lasting impacts<br />

and people tend to follow laws they believe in<br />

and have helped create.<br />

<strong>The</strong> global south needs to lead initiatives that<br />

jointly safeguard the future of fish and fishers,<br />

a scenario that will require a fundamental<br />

‘behavioural transformation’ in the offices of<br />

legislators.<br />

It takes trust, true collaboration, mutual<br />

respect, and equal benefit sharing for longterm<br />

sustainability of natural resources and<br />

conservation of imperilled fauna. I side with both<br />

fish and fishers to conserve our marine fauna.<br />

• Alifa B. Haque (alifa.haque@biology.ox.ac.uk; alifa.<br />

haque@du.ac.bd)<br />

Doctoral Researcher<br />

NBSI, Department of Biology, University of Oxford.<br />

Also affiliated with British Antarctic Survey.<br />

www.mba.ac.uk<br />

october 2022

14<br />

f e a t u r e<br />

marine biology<br />

matters in the climate<br />

and biodiversity<br />

crisis<br />

Dan Laffoley sets out his views on how marine<br />

biology can save our seas.<br />

History shows that knowing about the natural world is<br />

fundamental to understanding and effective action.<br />

I refer to it as ‘knowing is halfway to doing’. Linnaeus<br />

‘named nature’, Darwin gave us the tree of life, and<br />

countless other experts built our body of shared knowledge<br />

of life on Earth. Now, the ways in which we apply all this<br />

knowledge to the climate and biodiversity crisis and how we<br />

relate to the environment is key if we are to take the right steps<br />

to restore our damaged world.<br />

We have understood the intertwined relationship between<br />

climate change, biodiversity loss, and our health and prosperity<br />

for some time on land, but it is only surprisingly recently that<br />

we have accepted that the same is true of the ocean and the<br />

world-dominating role our seas play in regulating conditions<br />

for life on Earth. For it is the ocean that every day absorbs a<br />

quarter of the human-generated carbon dioxide that is driving<br />

global warming, and the same ocean that has absorbed over<br />

90 per cent of the heat it generates in the atmosphere.<br />

Most of our world is ocean, and yet how often we forget that<br />

we owe a pleasant climate to the watery heart of our planet.<br />

Earth’s ancient history shows that if the climate gets too warm<br />

species go extinct, if it becomes too cold species go extinct,<br />

and that it is the ocean over millennia that has regulated things<br />

to be ‘just right’, so we all thrive. Perhaps we have become overabsorbed<br />

in the digital world that has arisen around us, and<br />

thereby more disconnected than ever from nature, for we have<br />

forgotten how fundamentally important simply knowing about<br />

nature has become to all our futures, and all the other species<br />

we coexist with.<br />

Key workers<br />

<strong>The</strong> COVID pandemic brought a new appreciation for key<br />

workers—those who made our world work while we were<br />

locked away at home: those who created successful vaccines,<br />

kept delivering food, and nursed us better when many became<br />

Figure 1. Continuous plankton recorder ‘cassette’ showing a rich<br />

plankton sample on the silk spool.<br />

so very ill from the virus. Our natural world in crisis also has<br />

key workers: the climatologists, the sociologists, and the other<br />

scientists who, day-in and day-out and behind the scenes, build<br />

the evidence of how the human population is evolving, how<br />

the climate is being changed, and how nature is being rapidly<br />

degraded in responding to such pressures. <strong>The</strong>ir knowledge<br />

informs the many decisions that we need to take to adapt,<br />

mitigate, conserve, and restore to rectify our decades of greed<br />

and overconsumption. It is not an overstatement to say that<br />

this knowledge and its application has a direct bearing on the<br />

wellbeing of us all and, ultimately, our survival as a species.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ocean is, unsurprisingly, a large part of this story, and<br />

marine biology has many such key workers. At the <strong>Marine</strong><br />

Biological Association it was the specialists who designed and<br />

deployed the continuous plankton recorders 1 to study plankton<br />

—the microscopic basis for the ocean food chain—who decades<br />

ago first detected gross changes in plankton composition<br />

1<br />

https://www.cprsurvey.org/<br />

2<br />

https://www.mba.ac.uk/what-we-do/our-science/coastal-ecology/<br />

3<br />

https://www.marlin.ac.uk/<br />

4<br />

https://www.dassh.ac.uk/<br />

october 2022<br />

www.mba.ac.uk

f e a t u r e 15<br />

Figure 2. Stalked or goose barnacles<br />

(Pollicipes sp.). MarLIN hosts<br />

information on over 850 marine<br />

species of the<br />

British Isles.<br />

Over-absorbed in the digital<br />

world, we have forgotten how<br />

fundamentally important<br />

simply knowing about nature<br />

has become.<br />

which was<br />

traced back to our<br />

changing and warming world (Fig. 1).<br />

It was the MarClim team 2 who, with<br />

foresight many years ago, rescued key data on<br />

climate-sensitive intertidal species, creating one of<br />

the largest such databases in the world, which now shows the<br />

true impact of climate change on the biology of our coasts. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

then helped inspire the creation of the marine climate change<br />

impacts initiative (MCCIP) that now enables the UK to lead the<br />

world in understanding how our seas are responding to climate<br />

change impacts. It was at the MBA in 1998 that the <strong>Marine</strong> Life<br />

Information Network (MarLIN) (Fig. 2) was established, creating<br />

the knowledge system for marine biodiversity for Great Britain<br />

and Ireland that still today informs decisions by governments<br />

on how to best protect and manage marine life. MBA experts<br />

at the Archive for <strong>Marine</strong> Species and Habitats Data (DASSH) 4<br />

invented and provided the tools and services for the long-term<br />

curation, management, preservation, and publication of marine<br />

species and habitats data within the UK and internationally.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se are just a few examples and there are many more, but<br />

without such key workers and their initiatives, the UK and other<br />

nations would simply not be able to understand, let alone have<br />

the ability to manage, their ocean spaces.<br />

Driving marine biology forward<br />

Thankfully, the world is now coming alive—albeit rather late<br />

in the day—to the growing understanding that ocean health,<br />

climate change, and biodiversity are all fundamentally<br />

intertwined. Given that the heart of our planet is blue, it is<br />

surprising that more attention and money is not invested in<br />

marine biology. It certainly needs to be, but strides continue<br />

to be made to make this happen. <strong>The</strong> MBA has helped drive<br />

the discipline forwards. It is one of the earliest ‘birthplaces’ of a<br />

concerted effort not only to understand the marine biology of<br />

our seas, but to share the knowledge gained.<br />

Since its formation at a meeting held in the rooms of the<br />

Figure 3. <strong>The</strong> squid Loligo vulgaris, whose giant axon enabled<br />

Hodgkin and Huxley to measure the action potential in nerves,<br />

opening up a golden era in the field of neurobiology.<br />

Royal Society in London on 31 March 1884 the MBA has<br />

generated many—largely unsung—key discoveries on how<br />

this blue part of the planet works, and indeed in humankind’s<br />

understanding of fundamental biology. It is, after all, associated<br />

with 60 Nobel Laureates through its long and illustrious history,<br />

notably Sir Alan Lloyd Hodgkin and Sir Andrew Huxley, who<br />

were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in<br />

1963 (see Fig. 3). That quality of work continues today at the<br />

Association’s laboratory at Plymouth, and modern times reflect<br />

new changes and investment to keep up the pace. Work has<br />

now begun on the first phase of Burwell Architects’ £20m<br />

refurbishment and extension of the MBA’s headquarters in<br />

Plymouth. <strong>The</strong> development of the <strong>Marine</strong> Microbiome Centre<br />

of Excellence project aims to create a world-class research<br />

centre focusing on the marine microscopic world.<br />

Alongside this, the MBA has teamed up with the University<br />

of Plymouth and Plymouth <strong>Marine</strong> Laboratory to create <strong>Marine</strong><br />

Research Plymouth. This tripartite cooperative venture will also<br />

help cement Plymouth as the ‘go to’ destination for all things<br />

marine in the UK. As the status of Plymouth as the UK’s Ocean<br />

City continues to go from strength to strength, so too does<br />

marine biology as a key part of the knowledge system that,<br />

increasingly, informs the critical decisions affecting the future of<br />

our world.<br />

© HANS HILLEWAERT<br />

• Dan Laffoley (danlaffoley@btinternet.com), Emeritus <strong>Marine</strong> Vice<br />

Chair IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas, and MBA<br />

Council member.<br />

www.mba.ac.uk<br />

october 2022

16<br />

f e a t u r e<br />

does marine biology<br />

have an image<br />

problem?<br />

MBA Deputy Director and Head of Policy and<br />

Engagement Matt Frost argues for a change in<br />

narrative around marine biology and the importance<br />

of the oceans.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ‘cool’ subject dilemma<br />

On one of my first days at university (back in the 1990s), a<br />

fellow fresher asked me the question all new arrivals ask<br />

each other: ‘so what are you studying?’ On hearing that my<br />

chosen degree was marine biology, the response was: what<br />

an ‘awesome’ subject, followed by, ‘I almost applied myself, as<br />

it would be such a great subject’. When I asked them why they<br />

hadn’t, they answered, ‘Well, I wanted to do something that<br />

was practical and useful; you know, helping solve the world’s<br />

problems’. This comment has always stuck with me. It has been<br />

formative in my own approach to being a marine biologist but<br />

also left me with the distinct impression that marine biology has<br />

an image problem.<br />

Does image matter?: <strong>The</strong> importance of<br />

perception<br />

Let’s consider marine biology in terms of education, where<br />

the ‘Blue-Planet effect’ 1 and the perception of the subject as<br />

‘exciting’ or ‘cool’ can have positive outcomes, with universities<br />

attracting top students. For many students, however, the<br />

hoped-for outcome of studying marine biology seems to be<br />

a career in academia and/or conservation, which aligns with<br />

the overwhelming focus on most undergraduate degrees. That<br />

a marine biology degree could also prepare you for a career<br />

in law, publishing, industry, entrepreneurship, policy (national<br />

and international), diplomacy, marine forensics, medicine,<br />

and a host of other areas in addition to the traditional fields<br />

of academia and conservation is not widely-appreciated. <strong>The</strong><br />

fact that marine biology is a challenging field to break into, or<br />

sustain a long-term career, can be partly linked to the narrow<br />

focus on what career pathways are available.<br />

<strong>The</strong> other issue when it comes to career opportunities is that<br />

the lack of jobs also reflects the broader funding landscape.<br />

At the recent UN Oceans Conference in Lisbon, it was noted<br />

that of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the one<br />

with the least funding was SDG14 ‘Life Below Water’, i.e. the<br />

one related directly to the oceans. Only about 1.6 per cent of<br />

overseas aid or Official Development Assistance (ODA) funding<br />

is marine focused 2 and, on average, countries devote only 1.7<br />

per cent of their national research budgets to marine research<br />

(‘funding for ocean science is largely inadequate’) 3 . Funding for<br />

marine science is often compared unfavourably with funding<br />

for space research, but in most countries, it suffers equally in<br />

comparison with funding for medicine, defence, technology,<br />

and other research areas.<br />

<strong>The</strong> inference from this imbalance is that many governments<br />

worldwide have failed to be convinced of the value of<br />

investment in marine biological research over and against<br />

other areas. Governments are mainly focused on economic<br />

growth and responding to voters’ key concerns, such as the<br />

economy, health, security, and education. Discussions around<br />

marine protected areas or managing biodiversity in large<br />

swathes of the ocean that most people know nothing about<br />

inform all these key concerns, but this link isn’t obvious and<br />

some in power can therefore see marine biology more as a<br />

luxury than a necessity.<br />

october 2022<br />

www.mba.ac.uk

f e a t u r e 17<br />

<strong>Marine</strong> biologists leading on solutions for key global challenges.<br />

Changing the narrative—marine biology in<br />

the 21st century<br />

At a global level, there was a strong message from Lisbon<br />

that we must be much better in showing how marine science<br />

is linked to a broader range of SDGs than just SDG14. For<br />

example, it was pointed out at the 8th interactive dialogue on<br />

the final day (Leveraging interlinkages between Sustainable<br />

Development Goal 14 and other Goals towards the<br />

implementation of the 2030 Agenda’) that failure to achieve<br />

Goal 14 and its targets related to sustainable fisheries could<br />

seriously undermine achievement of SDG2 (Zero Hunger)<br />

goals on food security, hunger, and nutrition. <strong>The</strong> same can be<br />

said for many of the other SDGs, with marine biologists today<br />

working on SDGs ranging from health and wellbeing (SDG3<br />

Good Health and Well-being), pollution (SDG6 Clean Water<br />

and Sanitation) blue growth (SDG8 Decent Work and Economic<br />

Growth), capacity building (SDG10 Reduced Inequalities),<br />

climate change (SDG13 Climate Action) to science diplomacy<br />

(SDG16 Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions). This is not<br />

comprehensive, but whilst SDG links are well-documented<br />

in the literature, the message is not being heard clearly by<br />

governments and funding bodies.<br />

Much of the issue is in our communication rather than in<br />

practice. <strong>Marine</strong> scientists are at the forefront of solutionoriented<br />

science, addressing key issues of our time such as<br />

climate mitigation (nature-based solutions); sustainable futures<br />

(e.g. renewable energy); food security (fisheries, aquaculture);<br />

and oceans and human health (including microplastics in the<br />

food chain), to name but a few. Unfortunately, marine biologists<br />

leading on solutions for key global challenges is rarely the<br />

image that comes to mind when the subject is mentioned, and<br />

this is where we need to shout louder about this work. Another<br />

image of a beautiful or unusual sea creature may make our<br />

websites look nice or attract attention on social media (and<br />

they do have their place), but we also need people to see that<br />

marine biologists are ‘making a difference’ to society and the<br />

world at large.<br />

This brings the discussion back full circle to the comment I<br />

received as a fresh-faced student and how we promote marine<br />

biology to a new generation. <strong>The</strong> current negotiations on Areas<br />

of Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) are a prime<br />

example of where marine scientists and environmentalists are<br />

bringing experience and expertise to bear, not just on marine<br />

biodiversity but on issues of global equity, justice and human<br />

rights. <strong>The</strong> contribution of marine biology to these types of issue<br />

needs to be demonstrated to students, governments, funders<br />

(public and private), and to the wider public if we are going be<br />

persuasive in attracting the required resources. Had I known this<br />

in my university days, then perhaps a better answer would have<br />

been: ‘If you want to help solve some of the major issues faced<br />

by the world today – why not try marine biology’.<br />

• Matt Frost (matfr@mba.ac.uk), Head of Policy and Engagement/<br />

MBA Deputy Director<br />

1<br />

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/jan/12/blue-planet-effectwhy-marine-biology-courses-booming<br />

2<br />

https://oursharedseas.com/funding/<br />

3<br />

Arico et al. (2020). Global ocean science report 2020-charting capacity for<br />

ocean sustainability. UNESCO.<br />

© 2020 MARINE BIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION<br />

www.mba.ac.uk<br />

october 2022

18<br />

f e a t u r e<br />

meeting<br />

BIG CHALLENGES<br />

withbig solutions<br />

Daniela Sturm looks at the pros and cons of scaling-up <strong>Marine</strong><br />

Protected Areas (MPAs) to address global marine conservation goals.<br />

© Jordan Robins / Ocean Image Bank<br />

Above: Turtle at sunset,<br />

Great Barrier Reef,<br />

Australia.<br />

<strong>The</strong> world’s ocean is crucial for transport,<br />

trade, as a sink for our waste products,<br />

and as a source of food and materials.<br />

Throughout human history these<br />

resources have been used with little concern<br />

for how the ocean will be impacted over time.<br />

However, overexploitation, especially throughout<br />

the 20th century, has led to sharp declines in<br />

the state of many marine ecosystems and the<br />

services they provide.<br />

Overfishing is a particular cause for concern,<br />

as it may lead to simplified food webs and<br />

functional extinction of certain species. Although<br />

predictions that ‘we will all be eating jellyfish<br />

sandwiches’ have not yet come to pass, the<br />

advice from scientists is clear: declare large areas<br />

of the ocean off-limits to fishing and all other<br />

extractive uses, and reduce fishing capacity.<br />

Consequently, the High Ambition Coalition for<br />

People and Wildlife (an intergovernmental group<br />

of over 90 countries) is championing a deal to<br />

protect 30 per cent of terrestrial and marine<br />

habitats by 2030 (30x30). Over 100 nations have<br />

now committed to this ambitious target, but<br />

it will require a substantial increase in marine<br />

protected areas and in the quality and nature of<br />

management.<br />

<strong>Marine</strong> protected areas (MPAs) are designed<br />

to restrict human activity for a particular purpose,<br />

usually conservation. <strong>The</strong> International Union<br />