You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

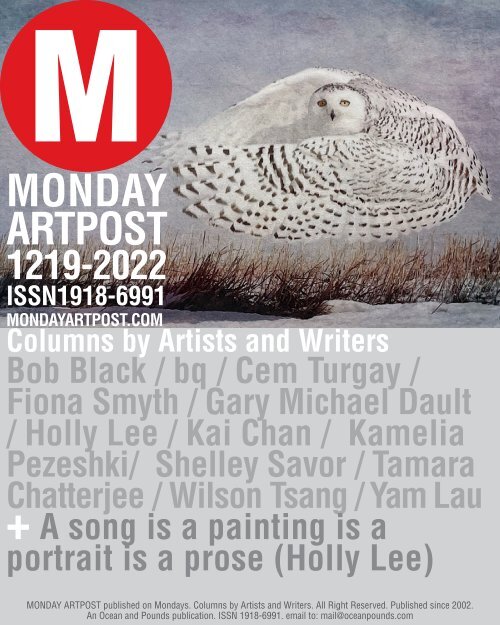

<strong>MONDAY</strong><br />

<strong>ARTPOST</strong><br />

<strong>1219</strong>-<strong>2022</strong><br />

ISSN1918-6991<br />

<strong>MONDAY</strong><strong>ARTPOST</strong>.COM<br />

Columns by Artists and Writers<br />

Bob Black / bq / Cem Turgay /<br />

Fiona Smyth / Gary Michael Dault<br />

/ Holly Lee / Kai Chan / Kamelia<br />

Pezeshki/ Shelley Savor / Tamara<br />

Chatterjee / Wilson Tsang / Yam Lau<br />

+ A song is a painting is a<br />

portrait is a prose (Holly Lee)<br />

<strong>MONDAY</strong> <strong>ARTPOST</strong> published on Mondays. Columns by Artists and Writers. All Right Reserved. Published since 2002.<br />

An Ocean and Pounds publication. ISSN 1918-6991. email to: mail@oceanpounds.com

Greenwood<br />

Kai Chan<br />

Study<br />

paper, wire

Poem a Week<br />

Gary Michael Dault<br />

Painters I like<br />

I like a painter<br />

whose fists<br />

beat on the canvas<br />

who cuts pigment<br />

into slices<br />

with a thumbnail<br />

whose boots<br />

are blackened with ink<br />

who gets painted<br />

into the spidery corners<br />

of studio time<br />

I like painters<br />

perpetually seated in moonlight<br />

always tyrannizing<br />

their freshly laid eyes<br />

I like painters<br />

who refuse all help<br />

who will piss<br />

on a candle flame<br />

give me a painter<br />

who meanders like a thread<br />

beneath the creaking<br />

of the crepuscular sun

ART LOGBOOK<br />

Holly Lee<br />

Michael Heizer’s City<br />

1. A city in the ocean of time<br />

https://gagosian.com/quarterly/<strong>2022</strong>/08/16/essay-a-city-in-the-ocean-of-time/<br />

2. After 50 years, Michael Heizer has finished his “City” in the desert<br />

https://www.collater.al/en/michael-heizer-city-desert-nevada-design/<br />

3. A mammoth artwork is born: Michael Heizer’s City opens in brutal Nevada desert after 50 years<br />

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/<strong>2022</strong>/aug/28/mammoth-artwork-michael-heizer-citynevada-desert<br />

4. ATTEMPTING TO SKATE MICHAEL HEIZER’S MEGA SCULPTURE IN THE DESERT (video 6:39)<br />

https://www.jenkemmag.com/home/<strong>2022</strong>/09/21/attempting-to-skate-michael-heizers-megasculpture-in-the-desert/<br />

5. Archived news story from KSL.com: Huge, top-secret sculpture taking shape in desert (video<br />

4:41)<br />

https://www.ksl.com/article/32203469/huge-top-secret-sculpture-taking-shape-in-desert<br />

6. What Do Native Artists Think of Michael Heizer’s New Land Art Work?<br />

https://hyperallergic.com/763203/what-do-native-artists-think-of-michael-heizers-new-land-artwork/

… 談 笑 間 …<br />

Yam Lau

Leaving Taichung<br />

Station<br />

Bob Black<br />

The Cemetery for the Companionless<br />

“You can call me a thief if you like, a thief of ceremonies”--Fleur Jaeggy<br />

red lanterns sway upon the hip of night in guard of landlords who proffer unease and damp lungs<br />

in search of firefly and candle and those who might be, forever her, hungry in the alley sway--<br />

pictured and scampering and aflight,<br />

you dug in and dug upon the bone rags of the city, crepuscular and carnal from lost peace<br />

even-tiding the long lampposts, the barking pull of the food market stall for single evenings,<br />

wet bones twig and stretch from window’s scratch, branches just so,<br />

the twilight calligraphy kneels down next us and softens the soil, green with cadaver and lunglost<br />

night,<br />

their voices adrift, your rowing twilight<br />

eddies and names a shoaded and spaded vein upon the hillside,<br />

our ocean bed looking over the forlorn & foretold place, the poles of winter precarious in their<br />

certainty<br />

is it some graveyard singing<br />

the chanting ocular and the disappearing gust along the rakes,<br />

the life here in the high-browse corner of the city, our life a pandemonium of rust<br />

the ghouls pandemic and the letters we marked red in the candlelight and our unsewed trust--<br />

recall when your mother struck you and the sun went unglued, undiscussed.<br />

now risen, the chaperoned evening unbuckles right, negotiated kettles of time and weeds upturned<br />

a listing of a future nest, alright:<br />

to rhyme the darkness with ringing, song and shell,<br />

to grattle and grass the rattle between an elbow and the oxbow of concordant you<br />

to rooftop the tarred city lights<br />

to unshovel the world a kettle of ghosts, swaying and singing up barley brick<br />

--the pail of all this going clanging against the cedar doors and slab block walls, rhyming the night<br />

blue.

a turn of the clock and a porter held a brass box, face lock<br />

oxidizing the stiff and the matter of the matrilineal<br />

a pocket compass ticking the sky calendar and the city longitudinal and longing: the dead babies<br />

the rambling cats in the dirt, the bottles tossed onto the sky, the secrets needled along the riverbank<br />

the cacophony of oblivion tapped out in the orchestra of your heart and cobblestone feet:<br />

there is no pronoun any longer shadowed by the lone tree<br />

there is no pronoun any longer unkeyed<br />

there is no pronoun any longer<br />

there is no pronoun<br />

there is no, any longer<br />

behind us brevity, dissolution, cheer her at last,<br />

the torn glove, the darkened skirt, the innervated boot and your verbs running release<br />

an interlocking, blurrish enumerated vocabulary and we poured,<br />

sinewy and artery and word puzzle,<br />

all of us, some of you and a clove of me, together untackled and wettened,<br />

poured out forever and into our some canine limitlessness--<br />

a cemetery for the companionless.<br />

yet their lives scribbled-up foam, a spew down from the body into a golem shaping<br />

this inconvenient world and the alchemy and the algebra and the clocks of Middle Asia<br />

our preternatural dipping and dampening, earth to worm and soil to ephemeral,<br />

the divesting and the marriage of all we know and would become, swarming our-ward<br />

you and I and all the rest, bedfellows and heaven’s crew, and ocean wrek<br />

the outbreak of us downing and coming alive long after our bones and sinews into the sable<br />

the indeterminate eternal sea.<br />

for: Holly and Ka-sing Lee

The Photograph<br />

coordinated by<br />

Kamelia Pezeshki<br />

Snowy Owl Hover, 2016 by Wendi Schneider<br />

pigment ink on vellum over white gold leaf from the ’States of Grace’ series

Open/Endedness<br />

bq 不 清<br />

話 到 嘴 邊<br />

TIP OF THE TONGUE<br />

那 唯 一 一 次 沒 有 變<br />

成 欠 缺 水 仙 花 的 蝴 蝶<br />

你 也 決 定 了 下 贏<br />

那 盤 海 戰 棋<br />

That only time you turned<br />

Into a butterfly without daffodils,<br />

You also decided to win<br />

That game of Battleship.<br />

那 一 刻 , 一 切 都 在 你 的<br />

腦 海 裡 發 生 , 然 後 落 到<br />

紙 上 , 以 X 和 O 呈 現 ⋯⋯<br />

一 大 堆 的 策 略<br />

It’s all happening in your head<br />

At that moment, then down<br />

On paper, with the X’s and O’s…<br />

All these strategies.<br />

現 在 來 談 談 你 的 型 態 :<br />

你 演 繹 臂 與 腿 的<br />

方 式 正 像 那 種 葉 子<br />

在 雨 中 懸 蕩 的 概 念 , 它<br />

Now let’s talk about your form:<br />

The way you articulate your arms<br />

And legs is like the very notion of<br />

Leaves dangling in the rain, which<br />

反 映 了 我 們 對 必 然 性 謹 慎 的<br />

寬 容 。 我 們 必 須 對 系 統<br />

進 行 欺 詐 , 先 供 之 許 多 的<br />

隱 喻 , 然 後 是 偽 科 學 的 數 據<br />

Reflects our tolerance carefully<br />

Toward certainty. We must cheat<br />

The system by feeding it with many<br />

Metaphors, then pseudoscientific data,<br />

就 像 我 為 自 己 解 說 這 個 夢 的<br />

方 式 。 它 涉 及 一 邊 捏 造 事 實<br />

一 邊 離 開 前 往 新 的 日 出 , 而 在 那<br />

一 個 新 的 字 詞 在 等 待<br />

Like the way I explain this dream<br />

To myself. It involves making stuff<br />

Up as you move on to a new sunrise where<br />

A new word awaits.

CHEEZ<br />

Fiona Smyth

From the Notebooks<br />

(2010-<strong>2022</strong>)<br />

Gary Michael Dault<br />

From the Notebooks, 2010-<strong>2022</strong><br />

Number 158: Still Life in Time of War (November 17, <strong>2022</strong>)

TANGENTS<br />

Wilson Tsang<br />

Giant Wing

ProTesT<br />

Cem Turgay

Caffeine Reveries<br />

Shelley Savor<br />

Festive Skating

Travelling Palm<br />

Snapshots<br />

Tamara Chatterjee<br />

France (March, <strong>2022</strong>) – Failure to validate<br />

our program vouchers meant a change in<br />

plan. Instead I wandered around enjoying<br />

the blooming season amid the renovated<br />

gardenscape surrounding Les Halles. I took<br />

my time taking in the modernized plaza and<br />

entry into the commercial centre, the vintage<br />

construction now replaced by a glass and<br />

metal canopy. The short interlude included<br />

gazing at an effervescent queue, attempting<br />

to discover their clone (Lego) figurine. ‘Twas<br />

amusing to observe the lively expressions,<br />

before taking off to rejoin the troupe.

Holly Lee<br />

A song is a painting is<br />

a portrait is a prose<br />

(an essay)<br />

89 • The Golden Lotus •<br />

Footsteps of June<br />

(selected photographs)<br />

An excerpt from DOUBLE DOUBLE November issue <strong>2022</strong>

A song is a painting is<br />

a portrait is a prose<br />

written by Holly Lee<br />

From Barber to Agee to Evans<br />

The first time I heard James Agee’s words were set to music, and sung by a soprano<br />

with a beautiful voice. I didn’t know him then, and gradually get to know him a little<br />

more. Not enough. Because of the music, the words and the poetry, I was driven to buy<br />

his book A Death in the Family.<br />

Agee’s rapturous prose-poem, Knoxville: Summer, 1915 was written in less than an<br />

hour and a half, and on his revision, stayed 98 percent faithful to the original writing.<br />

When I heard the music for the first time, I immediately fell for it. I was eager to<br />

know, who’s the composer, who’s the lyricist, who performed it. It was Samuel Barber,<br />

who set Agee’s Knoxville to music, and the version that I’d heard was sung by Renée<br />

Fleming. Obviously, my knowledge in contemporary classical music is as limited as my<br />

proficiency in 20th Century literature. But that doesn’t matter, I’ve become infatuated<br />

by both composer and writer since.

Described as “lyric rhapsody” by Barber, he used about 1/3 of the prose-poem for<br />

the score, conjuring up a 16-minute dramatic song for soprano and orchestra. There<br />

is a universality of idyllic, nostalgic beauty in the work, that even for a person from<br />

the Far East could grasp and resonate. The shortened prose set in lines was already<br />

very impressive, but reading the original prose; I was enraptured with the free flow of<br />

language, the meticulous observation of everyday life in amplified details, sentences<br />

filled with humanity and purity of the heart.<br />

On the bookshelf there is an old book I bought in the late eighties, which I rarely<br />

touch, and remember only its approximate contents. It was about the Farm Security<br />

Administration project; about some photographs taken by Walker Evans and text<br />

written by James Agee—a documentation of the lives of three impoverished tenant<br />

farmers during America’s Great Depression. I bring this up because, after some twenty<br />

years, I finally picked up Walker Evans’s 650 pages biography and start reading. It<br />

was from this point I remember the book “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men”, the book<br />

I mentioned above. The book, with its photographs and text, left the world an indelible<br />

impression on the poverty-stricken American South in the 30s. In it, I found a written<br />

account of Agee by Evans. I was struck by its vividness and unconventional style of<br />

writing, full of wit, beaming with life and personality. It is a “written” portrait of James<br />

Agee. Walker Evans is not only a great photographer, he is unequivocally a brilliant<br />

writer.<br />

I could have ignored, and kept ignoring Agee’s prose and poetry, and Evans’s<br />

photography, had I not been touched incidentally by Barber’s Knoxville. Music leads<br />

to words, and words lead to imagery, which brings me back to writing. As I learn more<br />

about Barber’s music, I’m impacted by his Adagio for Strings, which I have heard<br />

before, but not knowing: it is one of the saddest compositions in contemporary classical<br />

music.<br />

The Original Sisters to The Golden Lotus<br />

Anita Kunz acknowledged women of significance, known or unknown, with her brush<br />

strokes. Recently she has created a substantial body of work, bringing illustrious<br />

females front and centre to the printed page, naming the book “Original Sisters”.<br />

Drawing one portrait a day, the two year lockdown period gave her plenty of quiet<br />

time to focus on this project. Most characters in the series are long gone, and some<br />

she was only made aware of from her friends. The way she portrayed the figures relied<br />

mainly on public sources, and images she found on the Internet—very generic, and<br />

generalized. With her experience and well-versed skill, she deftly picked up heat and<br />

intensity of the individuals, modified and idealized with her personal touch.<br />

In the portrait of Anna Akhmatova, she set her against a red background, her sharp<br />

profile characterized by the nasal bump, and a fringe. Her hair is tied back into a<br />

soft bun, a red bead necklace hung down her shoulders stressing their roundness by<br />

the low-cut V-shaped dress. One can almost hear Akhmatova’s line: you will hear<br />

thunder and remember me, and think: she wanted storms. Camille Claudel is another<br />

beguiling portrait. The overall tone of the painting clings to an earthly brown. Her head<br />

and shoulders are elongated; her hair unkempt, raining down in rings of frenzy; her<br />

face is like porcelain, cracked and broken like her mental state, her intelligence and<br />

virtuosity are reflected by the delicately painted French embroidered lace. After almost<br />

close to a century, Camille Claudel’s sculptures are widely accepted, and proclaimed<br />

as great as Rodin’s—her once teacher, mentor, and lover.<br />

As Kunz celebrates the achievement of distinguished women in pictures, I contemplate<br />

on the submissive roles Chinese women have endured over the centuries, ever more<br />

feeling the privilege of living in a better, freer world of gender and racial equality. In<br />

1989, I was invited to work on a multi-platform art project, which had incorporated<br />

dance, performance, drama, music and photography. It was based loosely on the<br />

Chinese classical novel: The Golden Lotus. The novel took place in the 12th century,<br />

and encompassed many female characters, which made me think about the three-inch<br />

golden lotus—the synonym for the bound feet of women. I proposed to take a suite<br />

of portraits of the artists. Not deliberately, but out of subconsciousness, many of the<br />

portraits I took possessed strong gestural bearings of the hands and feet.<br />

When I was asked to participate in The Golden Lotus Project, the Tiananmen Square<br />

protests had just started in China. My approach to the portrait series of the performers<br />

and musicians was not meant to be direct interpretation of the characters in the book,<br />

and the six weeks of protests in China ending in bloodshed perturbed me immensely. It<br />

reflected clearly in my portrait of the musician Peter Suart. Suart, a young English lad<br />

born in Hong Kong, was in Beijing during the incident. He was a first-hand witness

ut left the capital before the brutal crack down. We worked together on the idea of<br />

the shot. In the shooting session, he wore the leather trench coat he bought in Beijing,<br />

grabbing two spiky Indonesian musical instruments acting as sharp claws; he spread<br />

his wings and soared like an eagle. The background was an old poem, composed and<br />

made into woodcut by Ka-sing. The poem was about free will, and choice. Tea or<br />

coffee. My title of the work echoed these thoughts. It came to be: 89 • The Golden<br />

Lotus • Footsteps of June (1989) 八 九 • 金 瓶 梅 • 六 月 前 後 .<br />

taking off my wartime garments. I’m putting on my old time wear. Gently, gently, I’m<br />

releasing and combing my long-tangled hair. Before the mirror I stare, ornamenting my<br />

brow with gold floral print cut in pairs. Stepping outside, I’m calling to my comrades.<br />

Shocked and startled, not even my confidant recognizes me! Oh, my companions<br />

for twelve long years. Listen to me, and look. Some distance away, among the thick<br />

bushes, a male rabbit scurried north; a female rabbit looked vague and lost. Both<br />

running, dear mates, are you able to tell if this one a buck, or that one a doe?”<br />

Buck or Doe: The Ballad of Mulan 木 蘭 辭 , a re-imagination<br />

She became a warrior by necessity, at a time when well water could not be mixed with<br />

river water. She was that quiet water knitting from dawn to dusk; her sole music came<br />

from her own breathing; her loom click click and click click.<br />

A troubled, unrest heart. How was her old father to fight? The Khan was merciless;<br />

soldiers were just numbers, recruited fast and perished fast. She would take up the<br />

duty, cut her hair, bind her breasts, wear her boots, and head to the market. East to get<br />

a fine stead; west, a saddle; south, a bridle, and north a long whip. Farewell farewell<br />

my parents. By dusk I’d be resting by the Yellow River, another dusk on the black<br />

mountains of Mongolia. Your calling became so feeble, I couldn’t bear to hear.<br />

Ten thousand miles she rode and battled, swept through fields and mountain passes.<br />

The north wind blew, the gong hit at midnight. Her armour shimmered under cold,<br />

silvery light. For ten years she fought on countless battlefields, battered bodies laid<br />

bare, and unsettled. For ten years, she combated and survived, returned gloriously,<br />

kneeling to meet her emperor. On his high throne he offered her praise, high rank, and<br />

gold. All these to her, were moon in the water, flower in the mirror. All she asked for<br />

was a good horse, accompanying her in her toilsome journey, speeding her safely back<br />

to her village; back to home, sweet home.<br />

Postscript<br />

In our age, most people associate Mulan as a Disney cartoon character of Asian origin,<br />

a woman disguised as a man going to battle for his aging father. Mulan is a fictional<br />

folk heroine from China’s Northern dynasties (Northern Wei, 386-534 AD), a time<br />

when many famous Buddhist rock-cut cave temples were constructed at Yungang<br />

and Longmen. Mulan is believed to be of Chinese/Xianbei ancestry (no bound feet!).<br />

Mulan is perhaps even a tribal name, leaving the highly regarded heroine, like<br />

many others, anonymous. But her brave deeds have survived and inspired people for<br />

many centuries. The Ballad of Mulan is collected from oral traditions, transcribed<br />

into written language, as a beautiful rhymed song. Though there are many English<br />

translations of this ballad available on the Internet, I have the urge to re-imagining the<br />

scene, and re-writing it in a prose form.<br />

Her news of returning reached home faster than her feet. Her father, mother walked<br />

out of the city arm-in arm. Her neighbours all came out to greet. Her sister rouged her<br />

cheeks in rosy red; her brother whetted his knife for pigs and sheep.<br />

Entering from east chamber door, settling on west chamber bed, she sings, “I’m

Mui Cheuk Yin 梅 卓 燕<br />

performer

Peter Suart 彼 得 小 話<br />

musician

Kung Chi Shing 龔 志 成 , Peter Suart 彼 得 小 話<br />

musicians

Under the management of Ocean and Pounds<br />

Since 2008, INDEXG B&B have served curators, artists,<br />

art-admirers, collectors and professionals from different<br />

cities visiting and working in Toronto.<br />

INDEXG B&B<br />

48 Gladstone Avenue, Toronto<br />

Booking:<br />

mail@indexgbb.com<br />

416.535.6957