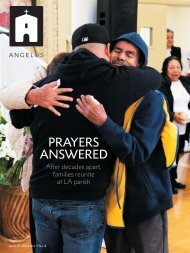

Angelus News | January 12, 2024 | Vol. 9 No. 1

On the cover: The Vatican’s new document Fiducia Supplicans on blessings for those in same-sex or “irregular” relationships has probably left the average Catholic with more questions than answers. What does it really say, and why is it so controversial? On Page 10, we break down the saga of the document’s reception with a sampling of some key reactions that illustrate what’s at stake. On Page 20, John Allen explains why the impact of Fiducia on the global Church may be more limited than we think.

On the cover: The Vatican’s new document Fiducia Supplicans on blessings for those in same-sex or “irregular” relationships has probably left the average Catholic with more questions than answers. What does it really say, and why is it so controversial? On Page 10, we break down the saga of the document’s reception with a sampling of some key reactions that illustrate what’s at stake. On Page 20, John Allen explains why the impact of Fiducia on the global Church may be more limited than we think.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

also dangerous, inviting at least three<br />

significant risks.<br />

The first would have been to reduce<br />

an exceptionally complex intellectual<br />

debate into some sort of rhetorical<br />

showdown; the second would have<br />

been to take sides between the two<br />

men, turning the movie into an apology<br />

of one side or the other. The third<br />

would have been to make an impossibly<br />

boring film: philosophical debates<br />

make for great university classes, but<br />

for a movie one needs action, plot, and<br />

character.<br />

Somehow, “Last Session” manages to<br />

avoid all three. It is a film that does not<br />

tell you what to think about God — it<br />

tells you how to think about him. In<br />

other words, it shows what elements<br />

should be put into the equation required<br />

to solve the “God problem.”<br />

The characters’ discussion of God<br />

(and many other subjects) is not just<br />

an exchange of learned opinions, but<br />

features flashbacks and references to<br />

their own lives. Freud, for example,<br />

tackles the problem of suffering (a<br />

theme Lewis dedicated entire books to)<br />

by recalling the premature death of his<br />

daughter and grandson. The issue of<br />

paternity and the father-son relationship<br />

is discussed with reference to the two<br />

characters’ fathers, and to Freud’s own<br />

relationship with his daughter, Anna.<br />

The result demonstrates an important<br />

truth: that the question of God<br />

is inextricably linked with how we<br />

interpret the facts, the events of our<br />

lives. As Lewis suggests at the end of the<br />

film, God is everywhere, the world is<br />

crowded with him, yet he is incognito.<br />

We can recognize his presence or be<br />

completely blind to it, depending on<br />

our disposition.<br />

In this “Last Session,” both characters<br />

get to play the role of the analyst, and<br />

both recline on Freud’s famous couch<br />

as patients. Both are faced with the discrepancies<br />

between what they preach<br />

and how they live, and the film does<br />

not shy away from the most controversial<br />

aspects of their lives.<br />

At the time, Lewis lived with a much<br />

older woman, the mother of a friend<br />

deceased in World War I. Questioned<br />

by Freud about this relationship, Lewis<br />

refuses to provide a definitive answer,<br />

but the film seems to imply they were<br />

lovers (a topic of disagreement among<br />

Lewis’ biographers).<br />

The film is merciless in its portrayal of<br />

Freud’s dysfunctional relationship with<br />

his last daughter, Anna, who followed<br />

in his footsteps to become a major<br />

figure in child psychoanalysis. Her<br />

relationship with him, as Freud himself<br />

admits to Lewis, is at the root of her<br />

lesbianism, of which Freud disapproves.<br />

He blocks the advancement of her<br />

career, keeps her away from relationships<br />

with both men and women, and<br />

tyrannically demands her constant<br />

presence and attention.<br />

It does not take a Dr. Freud to understand<br />

she needs a break from him, but<br />

Freud selfishly denies her the freedom<br />

his treatment is supposed to provide.<br />

But the most important element in the<br />

equation arrives when the discussion<br />

shifts to the topic of Freud’s impending<br />

death. “You believe you can outthink<br />

your fear by hiding behind your desk in<br />

your den of gods. But the truth is you<br />

are terrified,” Lewis attacks.<br />

But Freud reminds Lewis of his terror<br />

in front of death in a previous scene,<br />

when the two took refuge in a bomb<br />

shelter during what turned out to be<br />

a false air-raid alarm.<br />

You did not seem too<br />

eager to meet your<br />

creator then, Freud<br />

adds.<br />

“Because you know<br />

beyond all your fairy<br />

tales that he does not<br />

exist,” Freud tells him.<br />

“You see, you bury<br />

your doubts, your<br />

memories of the war,<br />

but at the core of your<br />

being, you are a coward.<br />

We are all cowards<br />

before death.”<br />

Thankfully, this film<br />

will be a disappointment<br />

to those who<br />

wanted to see Lewis<br />

destroy Freud and his<br />

arguments (or vice<br />

versa). If there’s one<br />

takeaway from “Last<br />

Session,” it’s that it is imperative for<br />

each man to question himself about the<br />

existence of God — and that finding<br />

the answer is not easy.<br />

As Freud understood, we are all<br />

conditioned by our desires, traumas,<br />

and complex personal histories, and<br />

tempted to fashion a god with the attributes<br />

of our earthly fathers. Lewis, for<br />

example, grew up with an absentee father,<br />

leading him to search for a father<br />

in heaven to replace his missing one.<br />

But the same preconditioning, the<br />

film suggests, goes in the opposite<br />

direction. Freud’s hatred of his father<br />

compelled him to deny the existence<br />

of God no less than Lewis’ desire for a<br />

father figure prompted him to imagine<br />

a divine one.<br />

By the end of the film, Freud admits<br />

that “it was madness to think that we<br />

could solve the greatest mystery of all<br />

times.” “There is a greater madness,”<br />

Lewis replies, “not to think of it at all.”<br />

“The real trouble” he adds, “is to<br />

come awake, to stay awake” to the possibility<br />

of his existence. This intelligent<br />

film can help with this endeavor.<br />

Stefano Rebeggiani is an associate<br />

professor of classics at the University of<br />

Southern California.<br />

Sigmund Freud in<br />

1921. | WIKIMEDIA<br />

COMMONS/MAX<br />

HALBERSTADT<br />

<strong>January</strong> <strong>12</strong>, <strong>2024</strong> • ANGELUS • 29