NATO – A Bridge Across Time - Newsdesk Media

NATO – A Bridge Across Time - Newsdesk Media

NATO – A Bridge Across Time - Newsdesk Media

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

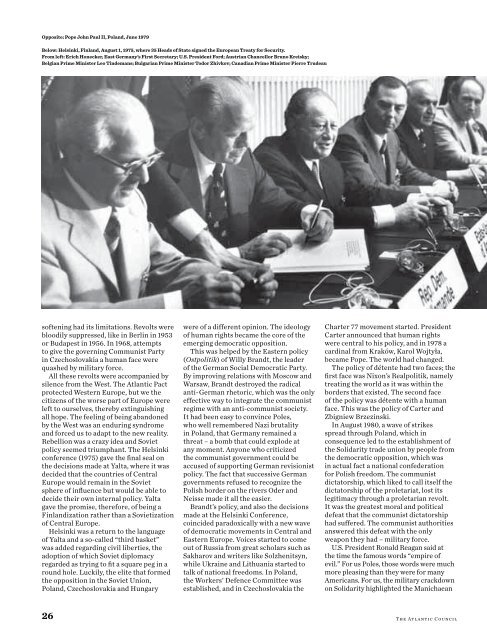

Opposite: Pope John Paul II, Poland, June 1979<br />

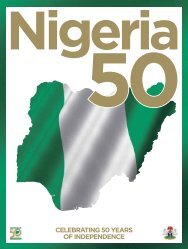

Below: Helsinki, Finland, August 1, 1975, where 35 Heads of State signed the European Treaty for Security.<br />

From left: Erich Honecker, East Germany’s First Secretary; U.S. President Ford; Austrian Chancellor Bruno Kreisky;<br />

Belgian Prime Minister Leo Tindemans; Bulgarian Prime Minister Todor Zhivkov; Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau<br />

softening had its limitations. Revolts were<br />

bloodily suppressed, like in Berlin in 1953<br />

or Budapest in 1956. In 1968, attempts<br />

to give the governing Communist Party<br />

in Czechoslovakia a human face were<br />

quashed by military force.<br />

All these revolts were accompanied by<br />

silence from the West. The Atlantic Pact<br />

protected Western Europe, but we the<br />

citizens of the worse part of Europe were<br />

left to ourselves, thereby extinguishing<br />

all hope. The feeling of being abandoned<br />

by the West was an enduring syndrome<br />

and forced us to adapt to the new reality.<br />

Rebellion was a crazy idea and Soviet<br />

policy seemed triumphant. The Helsinki<br />

conference (1975) gave the final seal on<br />

the decisions made at Yalta, where it was<br />

decided that the countries of Central<br />

Europe would remain in the Soviet<br />

sphere of influence but would be able to<br />

decide their own internal policy. Yalta<br />

gave the promise, therefore, of being a<br />

Finlandization rather than a Sovietization<br />

of Central Europe.<br />

Helsinki was a return to the language<br />

of Yalta and a so-called “third basket”<br />

was added regarding civil liberties, the<br />

adoption of which Soviet diplomacy<br />

regarded as trying to fit a square peg in a<br />

round hole. Luckily, the elite that formed<br />

the opposition in the Soviet Union,<br />

Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary<br />

were of a different opinion. The ideology<br />

of human rights became the core of the<br />

emerging democratic opposition.<br />

This was helped by the Eastern policy<br />

(Ostpolitik) of Willy Brandt, the leader<br />

of the German Social Democratic Party.<br />

By improving relations with Moscow and<br />

Warsaw, Brandt destroyed the radical<br />

anti-German rhetoric, which was the only<br />

effective way to integrate the communist<br />

regime with an anti-communist society.<br />

It had been easy to convince Poles,<br />

who well remembered Nazi brutality<br />

in Poland, that Germany remained a<br />

threat <strong>–</strong> a bomb that could explode at<br />

any moment. Anyone who criticized<br />

the communist government could be<br />

accused of supporting German revisionist<br />

policy. The fact that successive German<br />

governments refused to recognize the<br />

Polish border on the rivers Oder and<br />

Neisse made it all the easier.<br />

Brandt’s policy, and also the decisions<br />

made at the Helsinki Conference,<br />

coincided paradoxically with a new wave<br />

of democratic movements in Central and<br />

Eastern Europe. Voices started to come<br />

out of Russia from great scholars such as<br />

Sakharov and writers like Solzhenitsyn,<br />

while Ukraine and Lithuania started to<br />

talk of national freedoms. In Poland,<br />

the Workers’ Defence Committee was<br />

established, and in Czechoslovakia the<br />

Charter 77 movement started. President<br />

Carter announced that human rights<br />

were central to his policy, and in 1978 a<br />

cardinal from Kraków, Karol Wojtyła,<br />

became Pope. The world had changed.<br />

The policy of détente had two faces; the<br />

first face was Nixon’s Realpolitik, namely<br />

treating the world as it was within the<br />

borders that existed. The second face<br />

of the policy was détente with a human<br />

face. This was the policy of Carter and<br />

Zbigniew Brzezinski.<br />

In August 1980, a wave of strikes<br />

spread through Poland, which in<br />

consequence led to the establishment of<br />

the Solidarity trade union by people from<br />

the democratic opposition, which was<br />

in actual fact a national confederation<br />

for Polish freedom. The communist<br />

dictatorship, which liked to call itself the<br />

dictatorship of the proletariat, lost its<br />

legitimacy through a proletarian revolt.<br />

It was the greatest moral and political<br />

defeat that the communist dictatorship<br />

had suffered. The communist authorities<br />

answered this defeat with the only<br />

weapon they had <strong>–</strong> military force.<br />

U.S. President Ronald Reagan said at<br />

the time the famous words “empire of<br />

evil.” For us Poles, those words were much<br />

more pleasing than they were for many<br />

Americans. For us, the military crackdown<br />

on Solidarity highlighted the Manichaean<br />

26 The Atlantic Council