Includes HonorRoll ofDonors - Concordia College

Includes HonorRoll ofDonors - Concordia College

Includes HonorRoll ofDonors - Concordia College

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Concordia</strong> In China<br />

Professor Christopher J. Nagel led<br />

a student tour of China to see firsthand<br />

its rapid changes and learn<br />

more about its people’s culture,<br />

history, and traditions.<br />

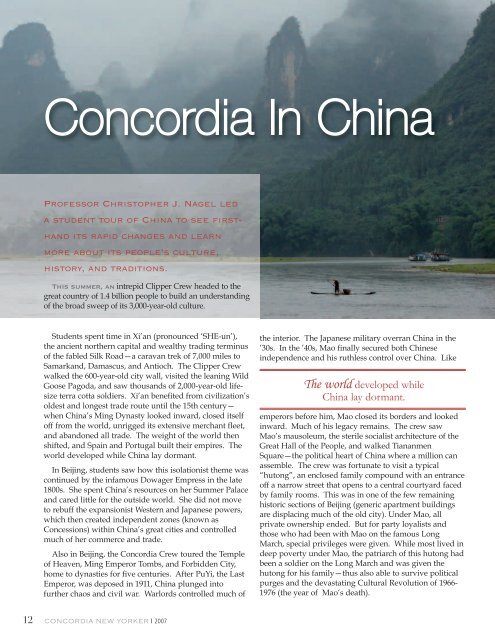

This summer, an intrepid Clipper Crew headed to the<br />

great country of 1.4 billion people to build an understanding<br />

of the broad sweep of its 3,000-year-old culture.<br />

Students spent time in Xi’an (pronounced ‘SHE-un’),<br />

the ancient northern capital and wealthy trading terminus<br />

of the fabled Silk Road—a caravan trek of 7,000 miles to<br />

Samarkand, Damascus, and Antioch. The Clipper Crew<br />

walked the 600-year-old city wall, visited the leaning Wild<br />

Goose Pagoda, and saw thousands of 2,000-year-old lifesize<br />

terra cotta soldiers. Xi’an benefited from civilization’s<br />

oldest and longest trade route until the 15th century—<br />

when China’s Ming Dynasty looked inward, closed itself<br />

off from the world, unrigged its extensive merchant fleet,<br />

and abandoned all trade. The weight of the world then<br />

shifted, and Spain and Portugal built their empires. The<br />

world developed while China lay dormant.<br />

In Beijing, students saw how this isolationist theme was<br />

continued by the infamous Dowager Empress in the late<br />

1800s. She spent China’s resources on her Summer Palace<br />

and cared little for the outside world. She did not move<br />

to rebuff the expansionist Western and Japanese powers,<br />

which then created independent zones (known as<br />

Concessions) within China’s great cities and controlled<br />

much of her commerce and trade.<br />

Also in Beijing, the <strong>Concordia</strong> Crew toured the Temple<br />

of Heaven, Ming Emperor Tombs, and Forbidden City,<br />

home to dynasties for five centuries. After PuYi, the Last<br />

Emperor, was deposed in 1911, China plunged into<br />

further chaos and civil war. Warlords controlled much of<br />

12 CONCORDIA NEW YORKER | 2007<br />

the interior. The Japanese military overran China in the<br />

’30s. In the ’40s, Mao finally secured both Chinese<br />

independence and his ruthless control over China. Like<br />

The world developed while<br />

China lay dormant.<br />

emperors before him, Mao closed its borders and looked<br />

inward. Much of his legacy remains. The crew saw<br />

Mao’s mausoleum, the sterile socialist architecture of the<br />

Great Hall of the People, and walked Tiananmen<br />

Square—the political heart of China where a million can<br />

assemble. The crew was fortunate to visit a typical<br />

“hutong”, an enclosed family compound with an entrance<br />

off a narrow street that opens to a central courtyard faced<br />

by family rooms. This was in one of the few remaining<br />

historic sections of Beijing (generic apartment buildings<br />

are displacing much of the old city). Under Mao, all<br />

private ownership ended. But for party loyalists and<br />

those who had been with Mao on the famous Long<br />

March, special privileges were given. While most lived in<br />

deep poverty under Mao, the patriarch of this hutong had<br />

been a soldier on the Long March and was given the<br />

hutong for his family—thus also able to survive political<br />

purges and the devastating Cultural Revolution of 1966-<br />

1976 (the year of Mao’s death).