Review of Coliforms - National Health and Medical Research Council

Review of Coliforms - National Health and Medical Research Council

Review of Coliforms - National Health and Medical Research Council

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

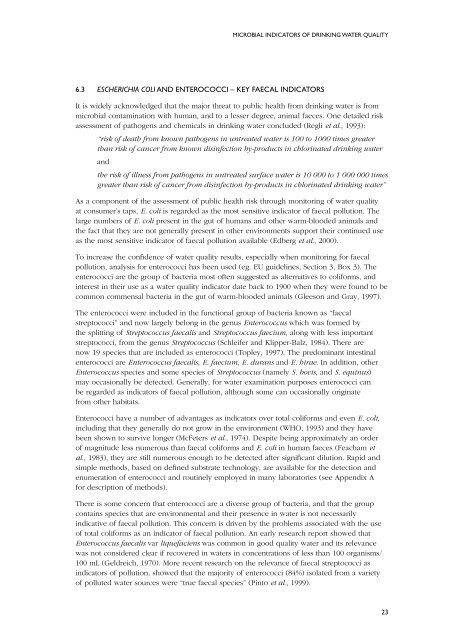

MICROBIAL INDICATORS OF DRINKING WATER QUALITY<br />

6.3 ESCHERICHIA COLI AND ENTEROCOCCI – KEY FAECAL INDICATORS<br />

It is widely acknowledged that the major threat to public health from drinking water is from<br />

microbial contamination with human, <strong>and</strong> to a lesser degree, animal faeces. One detailed risk<br />

assessment <strong>of</strong> pathogens <strong>and</strong> chemicals in drinking water concluded (Regli et al., 1993):<br />

“risk <strong>of</strong> death from known pathogens in untreated water is 100 to 1000 times greater<br />

than risk <strong>of</strong> cancer from known disinfection by-products in chlorinated drinking water<br />

<strong>and</strong><br />

the risk <strong>of</strong> illness from pathogens in untreated surface water is 10 000 to 1 000 000 times<br />

greater than risk <strong>of</strong> cancer from disinfection by-products in chlorinated drinking water”<br />

As a component <strong>of</strong> the assessment <strong>of</strong> public health risk through monitoring <strong>of</strong> water quality<br />

at consumer’s taps, E. coli is regarded as the most sensitive indicator <strong>of</strong> faecal pollution. The<br />

large numbers <strong>of</strong> E. coli present in the gut <strong>of</strong> humans <strong>and</strong> other warm-blooded animals <strong>and</strong><br />

the fact that they are not generally present in other environments support their continued use<br />

as the most sensitive indicator <strong>of</strong> faecal pollution available (Edberg et al., 2000).<br />

To increase the confidence <strong>of</strong> water quality results, especially when monitoring for faecal<br />

pollution, analysis for enterococci has been used (eg. EU guidelines, Section 3, Box 3). The<br />

enterococci are the group <strong>of</strong> bacteria most <strong>of</strong>ten suggested as alternatives to coliforms, <strong>and</strong><br />

interest in their use as a water quality indicator date back to 1900 when they were found to be<br />

common commensal bacteria in the gut <strong>of</strong> warm-blooded animals (Gleeson <strong>and</strong> Gray, 1997).<br />

The enterococci were included in the functional group <strong>of</strong> bacteria known as “faecal<br />

streptococci” <strong>and</strong> now largely belong in the genus Enterococcus which was formed by<br />

the splitting <strong>of</strong> Streptococcus faecalis <strong>and</strong> Streptococcus faecium, along with less important<br />

streptococci, from the genus Streptococcus (Schleifer <strong>and</strong> Klipper-Balz, 1984). There are<br />

now 19 species that are included as enterococci (Topley, 1997). The predominant intestinal<br />

enterococci are Enterococcus faecalis, E. faecium, E. durans <strong>and</strong> E. hirae. In addition, other<br />

Enterococcus species <strong>and</strong> some species <strong>of</strong> Streptococcus (namely S. bovis, <strong>and</strong> S. equinus)<br />

may occasionally be detected. Generally, for water examination purposes enterococci can<br />

be regarded as indicators <strong>of</strong> faecal pollution, although some can occasionally originate<br />

from other habitats.<br />

Enterococci have a number <strong>of</strong> advantages as indicators over total coliforms <strong>and</strong> even E. coli,<br />

including that they generally do not grow in the environment (WHO, 1993) <strong>and</strong> they have<br />

been shown to survive longer (McFeters et al., 1974). Despite being approximately an order<br />

<strong>of</strong> magnitude less numerous than faecal coliforms <strong>and</strong> E. coli in human faeces (Feacham et<br />

al., 1983), they are still numerous enough to be detected after significant dilution. Rapid <strong>and</strong><br />

simple methods, based on defined substrate technology, are available for the detection <strong>and</strong><br />

enumeration <strong>of</strong> enterococci <strong>and</strong> routinely employed in many laboratories (see Appendix A<br />

for description <strong>of</strong> methods).<br />

There is some concern that enterococci are a diverse group <strong>of</strong> bacteria, <strong>and</strong> that the group<br />

contains species that are environmental <strong>and</strong> their presence in water is not necessarily<br />

indicative <strong>of</strong> faecal pollution. This concern is driven by the problems associated with the use<br />

<strong>of</strong> total coliforms as an indicator <strong>of</strong> faecal pollution. An early research report showed that<br />

Enterococcus faecalis var liquefaciens was common in good quality water <strong>and</strong> its relevance<br />

was not considered clear if recovered in waters in concentrations <strong>of</strong> less than 100 organisms/<br />

100 mL (Geldreich, 1970). More recent research on the relevance <strong>of</strong> faecal streptococci as<br />

indicators <strong>of</strong> pollution, showed that the majority <strong>of</strong> enterococci (84%) isolated from a variety<br />

<strong>of</strong> polluted water sources were “true faecal species” (Pinto et al., 1999).<br />

23