From flax to linen. Experiments with flax - Ribe VikingeCenter

From flax to linen. Experiments with flax - Ribe VikingeCenter

From flax to linen. Experiments with flax - Ribe VikingeCenter

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Flax<br />

Common <strong>flax</strong> (Linum usitatissimum L.) is a member of the family Linaceae, of which the genus<br />

Linum is the most common <strong>with</strong> more than 200 species (Høst 1982). The plant can grow <strong>to</strong> a good<br />

metre and has one or more slender stalks <strong>with</strong> relatively short lanceolate leaves. A short taproot<br />

has fibrous branches that may extend up <strong>to</strong> a metre in the ground, depending on soil conditions.<br />

Its Latin name means “very useful”, which it is, producing both edible seeds and spinnable fibres.<br />

The plant is a cultured form, which does not grow in nature, and is most likely developed from<br />

Linum Bienne (Mill.) (Helbæk 1959).<br />

Flax can be grown both for its seeds and for its fibres. Today the plant exists in two variants:<br />

Linum usitatissimum Humile (or L.u. crepitans) and Linum usitatissimum vulgare. The Humile<br />

variant is grown for its seeds. It is generally shorter, <strong>with</strong> larger leaves, and has a higher tendency<br />

<strong>to</strong> tiller. More stalks means more seeds per plant, which is beneficial in this production. With the<br />

vulgare variant, which is used for fibre production, tillering is less prevalent. It is also less<br />

desirable, as a single straight stalk from each plant produces the best quality fibre. It is not known<br />

when these two variants have separated, but it is generally assumed that this has happened in<br />

relatively recent times (Brøndegaard 1979).<br />

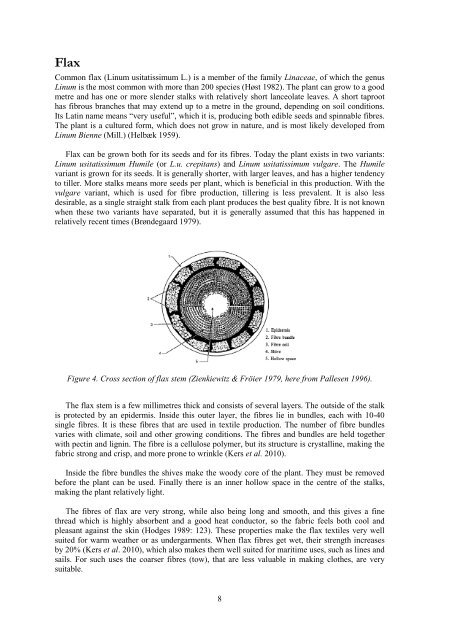

Figure 4. Cross section of <strong>flax</strong> stem (Zienkiewitz & Fröier 1979, here from Pallesen 1996).<br />

The <strong>flax</strong> stem is a few millimetres thick and consists of several layers. The outside of the stalk<br />

is protected by an epidermis. Inside this outer layer, the fibres lie in bundles, each <strong>with</strong> 10-40<br />

single fibres. It is these fibres that are used in textile production. The number of fibre bundles<br />

varies <strong>with</strong> climate, soil and other growing conditions. The fibres and bundles are held <strong>to</strong>gether<br />

<strong>with</strong> pectin and lignin. The fibre is a cellulose polymer, but its structure is crystalline, making the<br />

fabric strong and crisp, and more prone <strong>to</strong> wrinkle (Kers et al. 2010).<br />

Inside the fibre bundles the shives make the woody core of the plant. They must be removed<br />

before the plant can be used. Finally there is an inner hollow space in the centre of the stalks,<br />

making the plant relatively light.<br />

The fibres of <strong>flax</strong> are very strong, while also being long and smooth, and this gives a fine<br />

thread which is highly absorbent and a good heat conduc<strong>to</strong>r, so the fabric feels both cool and<br />

pleasant against the skin (Hodges 1989: 123). These properties make the <strong>flax</strong> textiles very well<br />

suited for warm weather or as undergarments. When <strong>flax</strong> fibres get wet, their strength increases<br />

by 20% (Kers et al. 2010), which also makes them well suited for maritime uses, such as lines and<br />

sails. For such uses the coarser fibres (<strong>to</strong>w), that are less valuable in making clothes, are very<br />

suitable.<br />

8