pdf 1 - exhibitions international

pdf 1 - exhibitions international

pdf 1 - exhibitions international

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

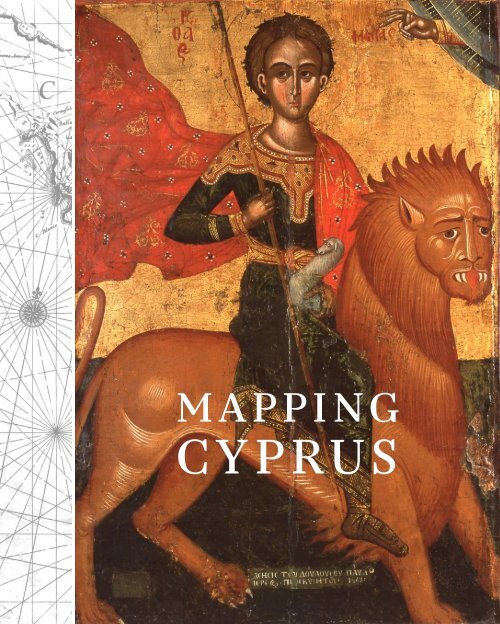

Mapping<br />

Cyprus

[22] [23]<br />

European Cartographers<br />

and Cyprus 1320–1918<br />

From the collection of<br />

Professor Andrew Nicolaides<br />

Andrew nicol Aides<br />

introduction<br />

Before the discovery of printing, maps of Cyprus and the rest of the world for<br />

that matter were drawn on vellum. Those used by sailors often showed only<br />

the outline of the shores with names of ports (portolan maps).<br />

Such were the maps used on the sailing ships of the crusades.<br />

The discovery of printing soon after 1450 using movable<br />

type made books available to a large number of people speeding<br />

up dissemination of knowledge. Until then manuscripts,<br />

which were expensive, were the privilege of the rich, the church<br />

and the noble. Strangely enough, the first printed atlases were<br />

not reproductions of portolan maps, but were based on the<br />

works of Ptolemy (Claudius Ptolemaeus 100–178 Ad) of Alexandria<br />

who was a mathematician, astronomer and geographer.<br />

Ptolemy worked in the great library in Alexandria where<br />

he had access to all accumulated knowledge including astronomy,<br />

geography and history. With this, with information he<br />

collected from travellers passing through Alexandria, culturally the centre of<br />

the Hellenic world, and with his own observations he produced two important<br />

books, his Almagest a manual on astronomy and his Geographike hyphegesis<br />

(known as Geographia or Cosmographia in some Latin editions), which was<br />

a summary of the geographical knowledge at 150 Ad and a guide to drawing<br />

maps of the known world. He provided instructions for drawing the map on a<br />

globe and for three possible projections on a plane surface; also for drawing a<br />

series of regional maps and a catalogue of approximately 8,000 localities with<br />

their coordinates of latitude and longitude.<br />

With the fall of the Roman Empire the classical Greek texts were lost to<br />

the West. Western scholars had been aware of Greek authors such as Homer,<br />

Plato, and Aristotle from references in Roman texts but they did not have any<br />

access to them. Thanks to the Byzantines who copied the Greek classics, many<br />

of which were taught at school, these texts including the Geographia survived.<br />

Today there are at least 53 known Greek manuscripts in existence, some with<br />

maps, the oldest dated 1300. The West became aware of the existence of Greek<br />

MAPPING CYPRUS EUROPEAN CARTOGRAPHERS AND CYPRUS<br />

Fig. 1: Cyprus. From Cosmographia Universalis<br />

(German edition) by Sebastian Munster,<br />

Basle, 1550; 96 x 150 mm

Fig. 2: Soria E Terra Sancta Nova Tabvla from<br />

La Geographia... by Giacomo Gastaldi, published<br />

by Giovanni Battista Pedrezano, Venice<br />

1548; 130 x 170 mm<br />

[24] [25]<br />

Classical scripts including Ptolemy’s books at the end of the 14th century<br />

when a delegation of Byzantine scholars visited Venice and Florence. For the<br />

Florentines this was a revelation. They were so impressed that several decided<br />

to learn Greek and translate them. Jacopo Angeli da Scarperia with the help of<br />

his teacher Manuel Chrysoloras, translated the Cosmographia into Latin during<br />

the years 1400–1407 making it available to the West for the first time in<br />

manuscript form.<br />

GeoGrAphicAl knowledGe At the time of ptolemy<br />

Ptolemy’s concept that the earth was a perfect sphere was based on the teachings<br />

of Pythagoras in the 6th century Bc and the proofs provided by Aristotle<br />

(384–322). He accepted the calculation of the earth’s circumference by Poseidonius<br />

of Apameia (130–52 Bc) of 18,000 miles (50 miles to an arc of 1 degree)<br />

rather than that of Eratosthenes of Cyrene of 25,200 miles (70 miles to an arc<br />

of 1 degree). This made the Earth circumference 18% smaller than the true<br />

size. His concept of the sun and planets in orderly orbits around the stationary<br />

earth at the centre of the universe with the stars fixed<br />

on an outer celestial sphere also rotating round the earth<br />

was the most popular at the time, while rejecting the heliocentric<br />

hypothesis of Aristarchus of Samos (310–230 Bc).<br />

The latitude of a locality was the angle of inclination<br />

from the equator and was between 00 and 900 depending<br />

on the distance from the equator. It could be determined<br />

from several measurements such as (a) the elevation of the<br />

north celestial pole above the horizon, (b) the ratio of a vertical<br />

stick (gnomon) to its shadow on the longest and shortest<br />

days of the year or (c) the ratio of the longest day of the<br />

year to the shortest, or even the length of the longest day.<br />

Thus, Ptolemy gives latitude as hours of sunlight.<br />

Longitude was measured eastward starting at the Fortunate (Canary)<br />

islands and Ptolemy drew his meridians at “intervals of a third of an equinoctial<br />

hour” i.e. at 50 intervals.<br />

“The Zodiacal circle”, the ecliptic, was recognised as the circle tilted at<br />

an angle of 240 traversed by the sun at a rate of just under a degree a day opposite<br />

to the rotation of the stars. The most northerly point of the ecliptic defined<br />

the Tropic of Cancer and the most southerly the Tropic of Capricorn.<br />

Tow further circles were recognised, the Arctic and Antarctic where the<br />

longest day of the year just reached 24 hours.<br />

Although the division of the circle to 3600 dates to Babylonian times<br />

and was used by the Greek astronomers and mathematicians,<br />

Ptolemy was the first to apply it in the use of terrestrial coordinates<br />

for specifying geographic positions.<br />

The habitable world of Ptolemy, the oikoumene, occupied<br />

one quarter of the earth, from just south of the equator to the<br />

64½ degrees north of the equator, and from the fortunate islands<br />

00 longitude to the end of the “Silk country” 1800 longitude.<br />

Thus, the width of Europe and Asia were exaggerated by 30%.<br />

Ptolemy believed that there was a southern land counterbalancing<br />

the land north of the equator so that the Indian Ocean was<br />

shown as a closed sea, but this land south of the equator was too<br />

hot to sustain human life. On the question whether the land on<br />

the other side of the earth was inhabited Ptolemy kept an open mind. The<br />

oikoumene was divided in three continents, Europe, Libye (Africa) and Asia.<br />

In the Geographia, Ptolemy states that to draw the world map on a globe<br />

is a method of ensuring correct representation of distances, but argues that<br />

globes are usually too small to show detail and he describes how to make<br />

projections on a flat surface. He gives detailed instructions how to make three<br />

different projections. His first projection is a conical one. In this projection<br />

east-west distances are portrayed in correct proportionality to north-south<br />

distances only along the parallel of Rhodes. His second projection is a pseudoconical<br />

one that preserves the ratio of the total latitudinal dimension to the<br />

total longitudinal dimension for all parallels. A third spherical projection is a<br />

modification of the second, but has not been used in any of the manuscript or<br />

printed Ptolemaic atlases. In addition to the world map, Ptolemaic atlases<br />

contain 26 regional maps with equidistant meridians and parallels: 10 for<br />

MAPPING CYPRUS EUROPEAN CARTOGRAPHERS AND CYPRUS<br />

Fig. 3: Asiae IIII Tab: From Tabvlae Goographicae<br />

Cl. Ptolomei... edited by Gerard<br />

Mercator, and printed by Godefrid von<br />

Kempen, Cologne, 1578; 345 x 465 mm

[26] Cat. 77 [27]<br />

Europe, 4 for Africa and 12 of Asia. Cyprus was in “Tabula Asiae IIII”, the forth<br />

table in the section of Asia.<br />

mAppinG the world<br />

If one looks at the world map of Ptolemy, the area that is most recognisable<br />

and closest to the world as we know it today is the region of the Mediterranean.<br />

However, it is the Mediterranean of Roman times with Roman places<br />

and names. The further away one looks the less recognisable the regions<br />

become. The first printed maps coincided with the beginning of the time of<br />

exploration and the discoveries of new lands. Following the trip of Columbus<br />

in 1492 and the circumnavigation of Africa by the Portuguese, the map of the<br />

world changed very fast; so did the maps of the Mediterranean regions not so<br />

much in land outline but mainly in terms of names and accuracy. The theme<br />

of the exhibition “European Cartographers and Cyprus” as well as the cartography<br />

of the Eastern Mediterranean cannot be seen in isolation without<br />

knowledge of the changes in other areas nor without a detailed knowledge of<br />

the work of Ptolemy who influenced subsequent European cartographers.<br />

The early Editions of the Geographia<br />

As indicated in the introduction, Ptolemy’s maps were a revelation in the West<br />

because for the first time they showed a wide audience what the world was<br />

like and the Geographia became one of the earliest texts to be published soon<br />

after printing was invented. With the exception of the Mediterranean region,<br />

the maps were far in advance of any others that existed. Such was the demand<br />

that by 1500 there were four printed editions with maps and two further<br />

impressions.<br />

The Bologna Edition 1477 The first printed edition was in Vicenza in 1475<br />

without maps. The first edition with maps was printed by Taddeo Crivelli in<br />

Bologna in 1477 (misprinted as 1462 on the front page). It included the reedited<br />

text of the Latin translation by Jacobo d’Angelo and 26 rather crudely<br />

Cipro, from Viaggio da Venetia...<br />

by Gioseppe Rosaccio and Giacomo Franco,<br />

Venice 1598<br />

98 x 174 mm<br />

MAPPING CYPRUS EUROPEAN CARTOGRAPHERS AND CYPRUS

[28] Cat. 89<br />

Cat. 90 [29]<br />

Christ (First half of the 16th century)<br />

St Nicolas (16th century)<br />

Arakapas, old church of Panayia Iamatiki, Diocese of Limassol<br />

Church of Chrysaliniotissa, Nicosia<br />

67 x 25,1cm<br />

67 x 25,1cm<br />

MAPPING CYPRUS EUROPEAN CARTOGRAPHERS AND CYPRUS

[30] Cat. 93 (top)<br />

Cat. 95 [31]<br />

Map (First half of the 16th century)<br />

Manuscript with map of Cyprus (16th century)<br />

67 x 25,1cm<br />

Ink on paper, 67 x 25,1cm<br />

Cat. 94 (bottom)<br />

Map (First half of the 16th century)<br />

67 x 25,1cm<br />

Collection xxx<br />

MAPPING CYPRUS EUROPEAN CARTOGRAPHERS AND CYPRUS

Les cartographes européens et Chypre<br />

(1320–1918) dans la collection<br />

d’Andrew Nicolaïdes<br />

Andrew nicol Aides<br />

introduction<br />

Avant la découverte de l’imprimerie, les<br />

cartes de Chypre, et plus généralement du<br />

reste du monde, étaient dessinées sur vélin.<br />

Les cartes utilisées par les navigateurs ne<br />

montraient souvent que les contours des<br />

rivages en indiquant les ports. Elles étaient<br />

de ce fait appelées portulans. C’est ce type<br />

de cartes qui fut utilisé sur les voiliers des<br />

croisades.<br />

Fig 1. Untitled Chart of the Eastern Mediterranean<br />

(265 x 325 mm) by Christian Wechelus, Hanover,<br />

1611 as drawn by Pietro Vesconte for Marino<br />

Sanudo’s “Liber Secretorum Fidelibus de Crucis”<br />

c. 1320.<br />

La découverte de l’imprimerie à caractères<br />

mobiles, peu après 1450, rendit les<br />

livres accessibles à un large public et accéléra<br />

fortement la diffusion des connaissances.<br />

Auparavant, les manuscrits, dont la<br />

réalisation était très coûteuse, avaient été le<br />

privilège des riches, de l’Église et de la<br />

noblesse. Fait assez singulier, les premiers<br />

atlas imprimés ne furent pas des reproductions<br />

de portulans, mais s’appuyèrent sur les<br />

travaux du mathématicien, astronome et<br />

géographe Claude Ptolémée d’Alexandrie<br />

(lat. Claudius Ptolemaeus, 100-178 apr. J.-C.).<br />

Ptolémée travaillait à la grande bibliothèque<br />

d’Alexandrie et avait donc accès à la somme<br />

[224] [225]<br />

de toutes les connaissances disponibles,<br />

notamment astronomiques, géographiques<br />

et historiques. Armé de ce vaste fonds et des<br />

informations qu’il recueillit auprès des voyageurs<br />

de passage à Alexandrie, centre culturel<br />

du monde hellène, mais aussi de ses<br />

propres observations, il produisit deux<br />

ouvrages importants : l’Almageste, un<br />

manuel d’astronomie, et la Geographike<br />

hyphegesis (que certaines éditions latines<br />

connaissent sous le nom de Geographia ou<br />

de Cosmographia), résumé des connaissances<br />

géographiques vers 150 apr. J.-C. et<br />

manuel de dessin de cartes du monde connu.<br />

Ptolémée explique comment en dessiner la<br />

carte sur un globe et donne des instructions<br />

pour réaliser trois types de projections sur<br />

une surface plane, mais aussi pour dessiner<br />

une série de cartes régionales. Il fournit<br />

enfin un catalogue d’environ 8000 localités<br />

avec leurs coordonnées longitudinales et<br />

latitudinales.<br />

Suite à la chute de l’Empire romain, les<br />

textes classiques grecs furent perdus pour<br />

l’Occident. Les lettrés occidentaux avaient<br />

connaissance des auteurs grecs comme<br />

Homère, Platon et Aristote par les citations<br />

qu’en donnaient les textes latins, mais n’y<br />

avaient aucun accès direct. Grâce aux Byzantins<br />

qui copièrent les classiques grecs, dont<br />

beaucoup étaient enseignés à l’école, ces<br />

textes survécurent, et notamment, avec eux,<br />

la Geographia,. À ce jour, on recense 53<br />

manuscrits grecs de cet ouvrage, certains<br />

illustrés de cartes, le plus ancien datant de<br />

1300. C’est dans le cadre de la visite d’une<br />

délégation d’érudits byzantins à Venise et à<br />

Florence à la fin du XIVe siècle que l’Occident<br />

prit connaissance de l’existence des<br />

classiques grecs et des ouvrages de Ptolémée.<br />

Pour les Florentins, ce fut une révélation.<br />

L’impression fut telle qu’ils décidèrent<br />

d’apprendre le grec et de les traduire. Aidé<br />

de son maître Manuel Chrysoloras, Jacopo<br />

d’Angelo da Scarperia traduisit la Cosmographia<br />

en latin dans les années 1400 à 1407,<br />

la rendant pour la première fois accessible à<br />

l’Occident sous forme de manuscrit.<br />

lA connAissAnce GéoGrAphique<br />

à l’époque de ptolémée<br />

La conception de Ptolémée selon laquelle la<br />

Terre était une sphère parfaite reposait sur<br />

les enseignements de Pythagore (VIe s. av.<br />

J.-C.) et les preuves de la sphéricité de la<br />

Terre apportées par Aristote (384-322 av.<br />

J.-C.). Ptolémée admettait le calcul de la circonférence<br />

de la Terre par Posidonius d’Apamée<br />

(130-52 av. J.-C.), qui l’avait fixée à 28 125<br />

km (78 km pour un degré d’arc), plutôt que<br />

celle de 39 375 km calculée par Érastosthène<br />

de Cyrène, diminuant ainsi la taille de la<br />

Terre de 29 % (?) par rapport à sa taille véritable.<br />

Sa conception d’un soleil et de planètes<br />

disposées en orbites ordonnées autour<br />

d’une Terre stationnaire occupant le centre<br />

de l’univers, les étoiles étant fixées sur une<br />

sphère céleste externe tournant elle aussi<br />

autour de la Terre, était la plus couramment<br />

admise à son époque, sachant qu’elle s’opposait<br />

à l’hypothèse héliocentrique d’Aristarque<br />

de Samos (310-230 av. J.-C.).<br />

La latitude d’un lieu correspondait à<br />

l’angle d’inclinaison de l’équateur et se<br />

comptait de 0 à 90 degrés selon sa distance<br />

par rapport à l’équateur. Plusieurs méthodes<br />

permettaient de la calculer : 1) hauteur du<br />

pôle nord céleste au-dessus de l’horizon ; 2)<br />

proportion entre un bâton vertical (gnomon)<br />

et son ombre aux jours le plus court et<br />

le plus long de l’année ; ou encore 3) proportion<br />

entre les jours le plus long et le plus<br />

court de l’année, voire sur la base de la durée<br />

du jour le plus long de l’année. C’est ce qui<br />

fait que Ptolémée donne la latitude d’un<br />

lieu en heures d’une journée.<br />

Concernant la longitude, elle était mesurée<br />

depuis l’est en partant des îles Fortunées<br />

ou îles des Bienheureux, aujourd’hui îles<br />

Canaries, et Ptolémée traçait ses méridiens<br />

comme « intervalles d’un tiers d’heure équinoxiale<br />

», c’est-à-dire à intervalles de cinq<br />

degrés.<br />

Le « cercle zodiacal » (l’écliptique) était<br />

reconnu comme le cercle formant un angle<br />

de 24 degrés par rapport à l’équateur, parcouru<br />

par le soleil en sens contraire de la<br />

rotation des étoiles à raison d’un peu moins<br />

d’un degré par jour. Le point le plus au nord<br />

de l’écliptique marquait le tropique du Cancer,<br />

et le point le plus au sud le tropique du<br />

Capricorne.<br />

D’autres cercles étaient également reconnus<br />

: les cercles Arctique et Antarctique<br />

marquaient le lieu où le jour le plus long de<br />

l’année durait exactement 24 heures.<br />

Bien que la division du cercle en 360°<br />

remontât à l’époque babylonienne et qu’elle<br />

fût utilisée par les astronomes et mathématiciens<br />

grecs, Ptolémée fut le premier à l’appliquer<br />

aux coordonnées terrestres pour spécifier<br />

des position géographiques.<br />

Le monde habitable de Ptolémée, l’oikouménè,<br />

couvrait un quart de la Terre. Dans le<br />

sens nord/sud, il s’étendait d’un peu au sud<br />

de l’équateur à 64,5° nord, et dans le sens<br />

est-ouest de la longitude 0° des îles Fortunées<br />

à la longitude 180° marquant l’extrémité<br />

orientale du « Pays de la soie ». La largeur<br />

de l’Europe et de l’Asie était donc<br />

exagérée de 30 %. Ptolémée croyait qu’il<br />

existait dans l’hémisphère sud une terre qui<br />

contrebalançait la terre située au nord de<br />

l’équateur, de sorte que l’océan Indien était<br />

présenté comme une mer intérieure, mais<br />

cette terre située au sud de l’équateur était<br />

trop chaude pour permettre la vie humaine.<br />

Quant à savoir si les terres situées de l’autre<br />

côté de la Terre étaient habitées, Ptolémée<br />

réservait son opinion. L’ œkoumène était<br />

divisé en trois continents : Europe, Libye<br />

(Afrique), Asie.<br />

Dans sa Geographia, Ptolémée explique<br />

que dessiner la carte du monde sur un globe<br />

est la méthode qui garantit la justesse des<br />

distances, mais que les globes sont habituellement<br />

trop petits pour montrer des détails.<br />

Il décrit donc la méthode permettant de réaliser<br />

des projections sur une surface plane et<br />

donne des instructions détaillées pour réaliser<br />

trois types de projections différents. Sa<br />

première projection est conique. Dans ce<br />

mode de projection, la proportionnalité<br />

entre les distances est-ouest et nord-sud est<br />

préservée, mais seulement le long du parallèle<br />

de Rhodes. Sa deuxième projection est<br />

pseudoconique, elle préserve la proportionnalité<br />

de la dimension latitudinale par rapport<br />

à toute la dimension longitudinale<br />

pour tous les parallèles. Une troisième projection,<br />

en l’occurrence sphérique, consiste<br />

en une modification de la deuxième<br />

méthode, mais n’a été utilisée dans aucun<br />

atlas ptolémaïque manuscrit ou imprimé.<br />

En plus de la carte du monde, les atlas<br />

ptolémaïques contiennent 26 cartes régionales<br />

présentant des méridiens et des parallèles<br />

équidistants : 10 cartes portent sur<br />

l’Europe, 4 sur l’Afrique et 12 sur l’Asie.<br />

Chypre se trouvait dans la « Tabula Asiae<br />

IIII », quatrième table de la section Asie.<br />

cArtoGrAphie du monde<br />

Quand on se penche sur la carte du monde<br />

de Ptolémée, la zone géographique la plus<br />

reconnaissable et la plus ressemblante au<br />

monde tel que nous le connaissons<br />

aujourd’hui, est la région méditerranéenne.<br />

Il s’agit toutefois d’une Méditerranée<br />

romaine avec des toponymes romains. Plus<br />

on s’en éloigne, moins les autres régions<br />

sont reconnaissables. Les premières cartes<br />

imprimées coïncident avec le début des<br />

grandes découvertes et l’exploration de<br />

terres inconnues. Après l’expédition de<br />

Christophe Colomb en 1492 et le contournement<br />

de l’Afrique par les Portugais, la carte<br />

du monde change rapidement. Ceci vaut<br />

également pour les cartes des régions méditerranéennes,<br />

mais moins en termes de<br />

contours des terres que principalement en<br />

termes de toponymes et de précision. Le<br />

thème de l’exposition « Les cartographes<br />

européens et Chypre » et la cartographie de<br />

la Méditerranée orientale ne peuvent être<br />

abordés isolément sans connaissance des<br />

évolutions dans d’autres domaines, ni sans<br />

une connaissance détaillée de l’œuvre de<br />

Ptolémée, qui exerça une influence déterminante<br />

sur les cartographes européens ultérieurs,<br />

et dont les erreurs dans la région<br />

méditerranéenne se perpétuèrent encore<br />

pendant une bonne partie du XVIIe siècle.<br />

Premières éditions de la Geographia<br />

Comme nous l’avons dit dans l’introduction,<br />

les cartes de Ptolémée furent une révélation<br />

en Occident parce qu’elles montraient pour<br />

la première fois à un large public à quoi ressemblait<br />

le monde, et la Geographia devint<br />

l’un des tout premiers textes publiés peu<br />

après l’invention de l’imprimerie. Exceptée<br />

la région méditerranéenne, ses cartes<br />

étaient très en avance sur toutes les cartes<br />

existantes. La demande fut telle qu’en 1500,<br />

quatre éditions enrichies de cartes et deux<br />

réimpressions supplémentaires avaient déjà<br />

été imprimées.<br />

L’édition de Bologne 1477 La première édition<br />

imprimée fut publiée sans cartes en<br />

1475 à Vicence. La première édition contenant<br />

des cartes fut imprimée en 1477 à<br />

Bologne par Taddeo Crivelli (l’année 1462<br />

MAPPING CYPRUS FRENCH TRANSLATIONS<br />

figurant en page de titre est erronée). Elle<br />

comprenait la réédition de la traduction<br />

latine de Jacopo d’Angelo et 26 cartes plutôt<br />

mal gravées sur cuivre. Le grand nombre<br />

d’inexactitudes et d’erreurs d’impression<br />

suggère que cette édition fut préparée à la<br />

hâte pour pouvoir revendiquer d’avoir été la<br />

première. En tout état de cause, ce fut un<br />

des premiers livres à présenter des gravures<br />

sur cuivre. L’année suivante, l’édition de<br />

Bologne devait être reléguée dans l’ombre<br />

par l’édition de Rome plus érudite et n’allait<br />

jamais être réimprimée.<br />

De cet atlas n’existent aujourd’hui que 26<br />

exemplaires connus.<br />

L’édition de Rome 1478 La deuxième édition<br />

de l’ouvrage de Ptolémée fut imprimée<br />

en 1478 à Rome par Arnoldus Bucking.<br />

Conrad Swenheym, qui avait appris le métier<br />

chez Gutenberg, commença à travailler aux<br />

gravures sur cuivre en 1474. Pendant qu’à<br />

Bologne, Taddeo Crivelli se hâtait pour être<br />

le premier à publier l’ouvrage, Swenheym<br />

travaillait lentement et soigneusement pour<br />

lui assurer une haute qualité. La justesse du<br />

texte et la finesse des gravures en fit la plus<br />

admirée de toutes les éditions du XVe siècle.<br />

L’utilisation d’une presse d’imprimerie plutôt<br />

que d’une presse à gravure était une nouveauté.<br />

Une autre nouveauté était l’impression<br />

des toponymes en fins caractères<br />

d’imprimerie – plutôt que leur gravure<br />

directe sur les plaques de cuivre. Une troisième<br />

nouveauté contribua à l’excellente<br />

qualité de la gravure, à savoir le fait que<br />

chaque carte était imprimée en utilisant<br />

deux plaques imprimées chacune sur une<br />

feuille séparée, les deux feuilles étant<br />

Fig 2. Asiae Tabula IV (370 x 540 mm); From Claudii<br />

Ptolemaei Alexandrini Philosophi Cosmographia,<br />

Edited by Arnoldus Bucking, Rome 1478

![01 -[BE/INT-2] 2 KOL +UITGEV+ - exhibitions international](https://img.yumpu.com/19621858/1/184x260/01-be-int-2-2-kol-uitgev-exhibitions-international.jpg?quality=85)