Density, Architecture, and Territory

ISBN 978-3-86859-436-2

ISBN 978-3-86859-436-2

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

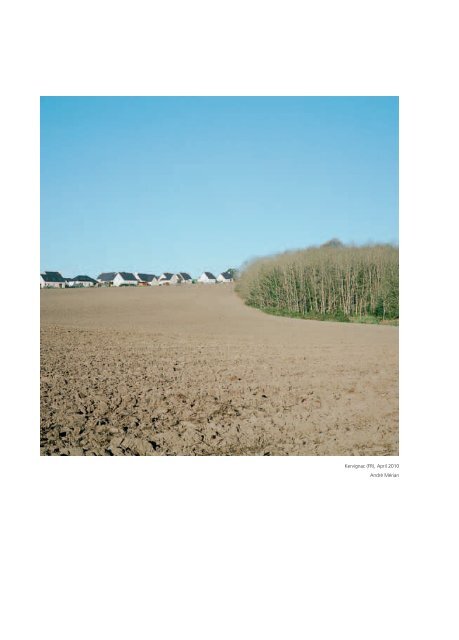

Kervignac (FR), April 2010<br />

André Mérian

<strong>Density</strong>, architecture, <strong>and</strong> territory<br />

Five European Stories<br />

Densité, architecture et territoire<br />

Cinq histoires européennes<br />

Jean-Pierre Pranlas-Descours (ed.)<br />

interviews / entretiens<br />

Kees Christiaanse – Marc Armengaud – Henri Bava – Alain Sallez

Contents / Sommaire<br />

8<br />

24<br />

Introduction / Introduction<br />

<strong>Density</strong>, a User’s Manual / Densité, mode d’emploi<br />

29<br />

67<br />

99<br />

135<br />

161<br />

<strong>Density</strong>, an Issue of L<strong>and</strong>-use / La densité, une question territoriale<br />

Introduction / Introduction<br />

Place <strong>and</strong> Heritage / Territoire et préservation – City Center / Centre-ville<br />

Compact Cities / La ville compacte – Edge City / Rurbain<br />

Regeneration <strong>and</strong> Densification / Reconquête et densification – Suburban / Péri-urbain<br />

L<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> Infrastructure / Paysage et infrastructure – Post-industrial / Post-industriel<br />

Polycentric Development / Développement polycentrique – Infrastructure / Infrastructure<br />

Interview / Entretien – Kees Christiaanse<br />

Programming Regional Facilities <strong>and</strong> Amenities / Programmer les territoires<br />

Introduction / Introduction<br />

Reactivate / Réactiver – City Center / Centre-ville<br />

Reconnect / Reconnecter – Edge City / Rurbain<br />

Recenter / Recentrer – Suburban / Péri-urbain<br />

Redevelop / Redévelopper – Post-industrial / Post-industriel<br />

Reunify / Réunir – Infrastructure / Infrastructure<br />

Interview / Entretien – Marc Armengaud<br />

L<strong>and</strong>scapes of <strong>Density</strong> / Les paysages de la densité<br />

Introduction / Introduction<br />

Creating a New Context / Réécriture contextuelle – City Center / Centre-ville<br />

Rural Grids <strong>and</strong> Cities Fabric / Tracés agricoles et trame urbaine – Edge City / Rurbain<br />

Scales of L<strong>and</strong>scape / Articulation des échelles – Suburban / Péri-urbain<br />

Port System Renewal / Permanence portuaire – Post-industrial / Post-industriel<br />

Intermodalities <strong>and</strong> Urban Intensity / Intensité urbaine – Infrastructure / Infrastructure<br />

Interview / Entretien – Henri Bava<br />

Defining New Housing Typologies / Nouvelles typologies d’habitations<br />

Introduction / Introduction<br />

Continuity <strong>and</strong> Diversity / Continuité et diversité – City Center / Centre-ville<br />

Individual Housing <strong>and</strong> Shared Spaces / Espace singulier et partagé – Edge City / Rurbain<br />

Shared Urban Practices / Mutualisation des pratiques urbaines – Suburban / Péri-urbain<br />

From Industrial to Liveable / De la friche au quartier – Post-industrial / Post-industriel<br />

Beyond Infrastructure / Habiter proche de l’infrastructure – Infrastructure / Infrastructure<br />

Project Requirements <strong>and</strong> Process / Les conditions du projet et processus<br />

Interview / Entretien – Alain Sallez<br />

îlot de l’Arc de Triomphe in Saintes – City Center / Centre-ville<br />

Leidsche Rijn in Utrecht – Edge City / Rurbain<br />

Bottière-Chênaie in Nantes – Suburban / Péri-urbain<br />

Sydhavnen in Copenhagen – Post-industrial / Post-industriel<br />

Shores of Lake Constance in Bregenz – Infrastructure / Infrastructure<br />

194<br />

196<br />

198<br />

Biographies / Biographies<br />

Bibliography / Bibliographie<br />

Credits / Crédits

Introduction<br />

Le passé du futur<br />

Nos sociétés contemporaines s’interrogent en permanence sur leur devenir urbain et<br />

sur l’horizon auquel elles sont confrontées : une métropolisation globale du territoire due<br />

à une densification inexorable et incontrôlée. Cette vision, greffée d’appréciations négatives,<br />

met à mal les relations jusqu’ici apaisées que nous entretenions avec le milieu dans lequel<br />

nous vivons.<br />

Mais, si l’on se place du point de vue de l’histoire de la formation des villes, la question<br />

centrale de l’accumulation et de la démultiplication du domaine bâti, souvent considérée<br />

comme un processus qui détruirait progressivement les paysages et la « nature », se pose<br />

différemment. Car l’histoire des villes européennes nous montre que la densification est<br />

le vecteur principal de leur formation.<br />

Jacques Le Goff 1 situait dans l’occident médiéval les fondements physiques de l’idée<br />

de communauté urbaine : ceux-ci se sont constitués à travers l’organisation de formes<br />

de densité qui limitaient et définissaient leur extension par étape. Les différentes<br />

représentations de ce modèle sociétal illustrent bien le concept des sociétés au Moyen Âge :<br />

celles-ci devaient déterminer clairement, tant d’un point de vue politique que physique,<br />

les relations entre ville et campagne.<br />

La ville, pilier du développement de la société, est protectrice : elle est l’essence même<br />

de l’idée d’un corps social solidaire. Parallèlement, elle entreprend de réguler un territoire,<br />

en dehors de son enceinte, en organisant l’agriculture et en dessinant les voies<br />

de communication destinées à assurer sa subsistance économique.<br />

Ce modèle archétypal, dont les figures et les représentations ont soutenu le développement<br />

urbain jusqu’à la fin du XIX e siècle, a maintenu la cohérence des sociétés urbaines. Il est<br />

encore possible d’en observer quelques exemples dans les villes qui furent à l’écart<br />

des gr<strong>and</strong>s bouleversements du siècle dernier, comme Sienne ou Genève. Mais à partir de l’ère<br />

industrielle, les modèles économiques et politiques qui ont émergé ont eu pour objectif<br />

de promouvoir une nouvelle organisation des territoires.<br />

Ils rejetaient particulièrement toute forme de densité urbaine, perçue alors comme une cause<br />

de promiscuité, de dégradation hygiénique des villes et d’exacerbation des conflits sociaux :<br />

Londres, à la fin du XIX e siècle, est l’illustration de cette dérive due à la densité.<br />

1 LE GOFF Jacques, La Civilisation de l’Occident médiéval, coll.« Les Gr<strong>and</strong>es Civilisations », Arthaud, Paris,1984.<br />

Detail of The Expulsion<br />

of the Demons from Arezzo<br />

Détail de Les diables chassés d’Arezzo<br />

Giotto,<br />

The Upper Church of San Francesco,<br />

Assisi, Italy, 1292–1296<br />

8

Introduction<br />

The Future Past<br />

Societies today ask many questions about their urban futures <strong>and</strong> about the planet-wide,<br />

metropolitan horizons that confront them with their seemingly inescapable <strong>and</strong> uncontrolled<br />

forms of density. Such a worldview is not only rife with negative judgments, but also means<br />

ab<strong>and</strong>oning forms of peaceful relations in the “milieus” in which we live <strong>and</strong> grow.<br />

Indeed, the key issue of accumulation <strong>and</strong> amplification of built space is often seen as being<br />

detrimental to “nature” in a general sense. Let us examine what this issue has meant to<br />

urban history <strong>and</strong> the development of cities.<br />

<strong>Density</strong> has always been important to the history of Western cities: it has played a leading<br />

role in the development of urban space <strong>and</strong> community life. As the historian Jacques<br />

Le Goff reminds us, 1 the physical foundations of the idea of cities as communities came<br />

together very early on in the Middle Ages. The organization of density was a defining<br />

quality of city spaces, which were demarcated <strong>and</strong> delimited every step along the way.<br />

Pictorial representations of these social models also made it clear that the mental<br />

constructions of medieval societies determined the relationship between city <strong>and</strong> country,<br />

from both a political <strong>and</strong> a physical st<strong>and</strong>point.<br />

Cities provide protection. They are the backbone of the evolution of society <strong>and</strong> the very<br />

essence of the idea of a unified social body. At the same time, they seek to regulate<br />

territories beyond their boundaries, organizing agriculture <strong>and</strong> patterns of communication,<br />

<strong>and</strong> thereby assure their own livelihood.<br />

The characteristics <strong>and</strong> representations of the city as an archetype influenced urban<br />

development up until the end of the nineteenth century, <strong>and</strong> have continued to maintain<br />

the cohesiveness of urban society ever since. Noteworthy examples can still be found within<br />

cities that have remained relatively aloof throughout the upheavals of the last century.<br />

From the industrial era onwards, new economic <strong>and</strong> political models have come to the fore,<br />

aiming to promote new forms of l<strong>and</strong> settlement <strong>and</strong> organization.<br />

These models—of which London at the turn of the nineteenth century was the quintessential<br />

example—first opposed density, rejecting it as being synonymous with promiscuity,<br />

the hygienic degradation of society, <strong>and</strong> the exacerbation of social conflicts.<br />

1 LE GOFF Jacques, Medieval Civilization 400–1500, 1988, (La Civilisation de l’Occident Médiéval, Arthaud,<br />

Paris, 1984).<br />

Parking Lot—Shopping Mall<br />

Parking - Centre commercial<br />

André Mérian,<br />

Coimbra, Portugal, 2002<br />

9

Densité, mode d’emploi<br />

Comprendre, illustrer et expliciter les formes de densité au sein des territoires contemporains<br />

est une entreprise complexe de par la diversité propre aux lieux de densité et la perception<br />

que nous en avons.<br />

La démarche proposée dans cet ouvrage croise cinq thèmes majeurs permettant<br />

d’approfondir et de mettre en perspective les questions liées à la densité :<br />

- la densité : une question territoriale<br />

- programmer les territoires<br />

- les paysages de la densité<br />

- nouvelles typologies d’habitations<br />

- les conditions du projet<br />

Ces thèmes sont abordés par les projets emblématiques que nous avons choisis<br />

car ils illustrent chacun des situations très différentes :<br />

- centre-ville : l’Îlot de l’Arc de Triomphe à Saintes (France)<br />

- rurbain : le quartier Langerak 2 à Utrecht (Pays-Bas)<br />

- péri-urbain : le quartier Bottière-Chênaie à Nantes (France)<br />

- post-industriel : le port de Sydhavn à Copenhague (Danemark)<br />

- infrastructure : le quartier de Seestadt à Bregenz (Autriche)<br />

Cet ouvrage procède par un approfondissement progressif du regard porté sur ces sites,<br />

partant du gr<strong>and</strong> territoire pour aller jusqu’à la dimension liée à l’habitabilité.<br />

Cette progression révèle l’enchaînement et l’articulation des décisions prises tout au long<br />

du processus de réalisation de ces cinq projets.<br />

Chaque chapitre correspond à un thème choisi, illustré par un code couleur.<br />

Le choix des projets a été fait à partir d’une analyse précise des qualités tant urbaines que<br />

paysagères et architecturales sur l’ensemble des échelles de l’aménagement spatial.<br />

Car une pensée structurée et déterminée sur le territoire n’a de légitimité que si elle<br />

s’incarne dans des actes architecturaux exemplaires.<br />

Tel est bien le caractère d’excellence de ces projets, qui, de par leur dimension, ne sont pas<br />

nécessairement exceptionnels, mais traduisent une éthique constante se déclinant à toutes<br />

les échelles et quelles que soient les situations dans lesquelles ils se déploient.<br />

24

<strong>Density</strong>, a User’s Manual<br />

Underst<strong>and</strong>ing, illustrating, <strong>and</strong> clarifying the forms of density within contemporary urban<br />

environments is no easy task. High density areas are indeed not only highly diverse but are<br />

also perceived in many different ways.<br />

In this publication, we chose to cross-examine densification through five key subjects:<br />

- <strong>Density</strong>, an Issue of L<strong>and</strong> Use<br />

- Programming Regional Facilities <strong>and</strong> Amenties<br />

- L<strong>and</strong>scapes of <strong>Density</strong><br />

- Defining New Housing Typologies<br />

- Project Requirements<br />

These subjects are addressed through iconic projects that illustrate different kinds of<br />

situations:<br />

- City Center: Îlot de l’Arc de Triomphe in Saintes (France)<br />

- Edge City: Langerak 2 district in Utrecht (The Netherl<strong>and</strong>s)<br />

- Suburban: Bottière-Chênaie district in Nantes (France)<br />

- Post-industrial: Sydhavnen harbor in Copenhagen (Denmark)<br />

- Infrastructure: the Seestadt district in Bregenz (Austria)<br />

This publication proceeds in stages <strong>and</strong> incrementally delves into more detail for each site,<br />

starting with the wider geographical context <strong>and</strong> finishing with liveability.<br />

This process reveals the structural links <strong>and</strong> logical sequences of the decisions that were<br />

made throughout the realization of the five projects.<br />

Each chapter corresponds to a given subject, which is illustrated by a color code.<br />

The choice of projects was made based on a precise analysis of their urban, scenic, <strong>and</strong><br />

architectural qualities at all levels of spatial planning. Structured <strong>and</strong> grounded thinking is<br />

indeed only legitimate if it materializes in exemplary architectural deeds.<br />

All the projects we have chosen to present here are significant, not necessarily in terms of<br />

their sheer size, but because they reflect exacting st<strong>and</strong>ards of quality <strong>and</strong> strong ethics that<br />

can be seen at all levels <strong>and</strong> in all situations where they have been carried out.<br />

25

5 km<br />

Urbanization in 1900<br />

Urbanization in 2010<br />

Leidsche Rijn<br />

Railway<br />

Roads<br />

Leiden<br />

Den Haag<br />

Delft<br />

Rotterdam<br />

Haarlem<br />

Gouda<br />

Amsterdam<br />

Utrecht<br />

Groeikern (New Town)<br />

Urbanization in 2010<br />

Leidsche Rijn<br />

Railway<br />

Recent Railway Line<br />

Freeway<br />

Hellevoetsluis<br />

5 km<br />

Spijkenisse<br />

Zoetermeer<br />

Haarlemmermeer<br />

Capelle aan den IJssel<br />

Purmerend<br />

Nieuwegein<br />

Almere<br />

Houten<br />

5 km<br />

Urbanization in 2010<br />

Groeikern (New Town)<br />

VINEX Sites<br />

Railway<br />

Freeway<br />

Den Haag<br />

Delft<br />

Rotterdam<br />

Leiden<br />

Haarlem<br />

Gouda<br />

Amsterdam<br />

Utrecht<br />

1994–2030<br />

26

1956 Urbanization<br />

1968 Urbanization<br />

Market Garden Cropl<strong>and</strong><br />

Nantes Bottière-Chênaie District<br />

La cité de Gr<strong>and</strong> Clos<br />

1948<br />

1917<br />

Horticultural L<strong>and</strong><br />

1917<br />

Horticultural L<strong>and</strong><br />

La Bottière<br />

Horticultural<br />

L<strong>and</strong><br />

Horticultural L<strong>and</strong><br />

Horticultural L<strong>and</strong><br />

Old Doulon<br />

500 m<br />

1968 Urbanization<br />

1999 Urbanization<br />

Tramway 1985<br />

La<br />

Bottière<br />

Schools<br />

Gohards Stream<br />

Old Doulon<br />

Lost of Local Identity<br />

500 m<br />

Public Utilities<br />

Retail Outlets<br />

Public Park<br />

Bus line 1<br />

Beaujoire<br />

Bus line 48<br />

T<br />

La Bottière<br />

T<br />

Nantes Center<br />

150 m<br />

Bus line 71<br />

Calquefeu<br />

Closeness Centrality:<br />

Neighborhood Level<br />

Old<br />

Doulon<br />

Metropolitan Centrality:<br />

Suburban Integration<br />

500 m<br />

200 m<br />

Planted Tree<br />

Meadows<br />

Waterfront Pedestrian or Cycle Promenade<br />

Footpath or Cycle Continuity<br />

Sports Facilities / Deck<br />

Educational, Recreational, or Cultural Facilities<br />

Public Transport / Bus<br />

Harbor Baths<br />

M<br />

Public Transport Stops / Stations<br />

Housing in Project Zone<br />

Housing<br />

Other Programs<br />

Railway Lines<br />

200 m<br />

O u t e r R i n g R o a d<br />

Locomotives<br />

Railway 1877<br />

Gohards Stream<br />

Freight Railway<br />

Cut-O f Line<br />

Sainte-Luce Road<br />

I ner Ring Road 1870<br />

I n e r R i n g R o a d<br />

Railway Station<br />

27

EDGE CITY<br />

r u r b a i n<br />

Leidsche Rijn in Utrecht (NL)

Leidsche Rijn in Utrecht (NL)<br />

<strong>Territory</strong> I Edge City I Statement<br />

Territoire I Rurbain I Constat<br />

Historical City, L<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> Agricultural Grids: The Groene Hart<br />

At the end of the nineteenth century, the central region of the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s between Rotterdam <strong>and</strong><br />

Amsterdam was still largely agricultural. Urban development took place over different parts of the<br />

country at the same time, <strong>and</strong> several medium-sized cities mushroomed despite the dominance<br />

of Amsterdam, which even as early as 1900 counted more than half a million inhabitants. Further<br />

underpinning these homogenous networks of settlement were the railways that were built from 1843<br />

onwards. The Groene Hart (literally, “green heart”) that would later become the leitmotiv of future<br />

planning initiatives was already a l<strong>and</strong>scape feature, <strong>and</strong> remained thinly populated.<br />

Ville historique, territoire et tracés agricoles : le Groene Hart<br />

À la fin du XIX e siècle, le centre des Pays-Bas, entre les villes de Rotterdam et d’Amsterdam, est encore<br />

très largement agricole. Le développement urbain s’est établi de manière concomitante sur différents<br />

points du territoire, donnant naissance à plusieurs villes moyennes de poids relativement équivalent,<br />

malgré la domination d’Amsterdam, regroupant déjà plus de 500 000 habitants en 1900.<br />

Les lignes de chemin de fer qui se développent à partir de 1843 soulignent davantage encore ce maillage<br />

homogène du territoire. Le Groene Hart – cœur vert – qui deviendra le leitmotiv des politiques<br />

de planification de ce territoire pour les années à venir est déjà très lisible et reste faiblement urbanisé.<br />

39

Entretien avec Kees Christiaanse<br />

<strong>Territory</strong> I Interview<br />

Territoire I Entretien<br />

Le modèle holl<strong>and</strong>ais<br />

Jean-Pierre Pranlas-Descours : Je propose de commencer cet entretien par la notion<br />

d’échelle territoriale. Est-ce finalement la bonne échelle pour penser la densité ?<br />

Afin de répondre à cette question, nous sommes partis dans cet ouvrage de l’exemple<br />

holl<strong>and</strong>ais de la R<strong>and</strong>stad et d’une situation de densité particulière sur le territoire d’Utrecht.<br />

Pensez-vous que le territoire holl<strong>and</strong>ais constitue une situation propice au développement<br />

de ces modèles de densité ? Pour quelles raisons ? Pourquoi dans d’autres pays européens<br />

cette densité ne parvient-elle pas à se construire ?<br />

Kees Christiaanse : Les Pays-Bas sont un gr<strong>and</strong> paradoxe ! D’une part, c’est un petit pays,<br />

certes très peuplé – la densité moyenne y est de 450 habitants par km² – et d’autre part,<br />

le développement urbain y est pensé à très gr<strong>and</strong>e échelle. En cela, le pays diffère<br />

de la Belgique, la Suisse ou le Danemark, où la propriété est beaucoup plus fragmentée,<br />

avec des tailles de parcelles réduites qui rendent le développement urbain plus résilient.<br />

Historiquement, le contrôle des phénomènes maritimes pour l’aménagement du pays est<br />

fondateur de l’organisation territoriale. Il a donné naissance à une société très collaborative,<br />

ainsi qu’à une culture d’ingénierie civile très poussée capable d’engager la mutation<br />

d’importantes surfaces du territoire. Qu’elles appartiennent à l’État, aux provinces ou<br />

aux communes, de très gr<strong>and</strong>es parcelles peuvent être aménagées d’un seul tenant.<br />

C’est pourquoi aux Pays-Bas le développement urbain s’établit à plus gr<strong>and</strong>e échelle que<br />

dans d’autres pays, pour un processus qui peut paraître plus rapide. Le risque est de voir<br />

se construire de vastes quartiers monofonctionnels qui n’offrent finalement que peu de mixité.<br />

L’horizon culturel largement majoritaire d’une société de propriétaires (60 à 80%<br />

des Holl<strong>and</strong>ais) est celui de posséder un logement de plain pied. Cette aspiration génère<br />

donc une densité assez faible.<br />

Cette condition suburbaine est bien sûr commune à de nombreux pays. Nous en arrivons<br />

à designer les Pays-Bas comme le « New Jersey de l’Europe »…<br />

Mais le fond du problème réside dans la trop gr<strong>and</strong>e facilité d’urbaniser les Pays-Bas :<br />

le prix des terrains est faible, ce qui ne favorise pas la création de situations de mixité<br />

ou de densité. C’est très différent en Suisse par exemple, où près de 60 % des ménages<br />

sont locataires de leur habitation et où le pourcentage d’appartements en étages est<br />

important. Les parcelles sont en moyenne beaucoup plus petites et les propriétés<br />

très fragmentées. Je pense que cette question de parcellaire est essentielle et j’imagine que<br />

l’on pourrait développer aux Pays-Bas un système de découpage artificiel du parcellaire<br />

afin de générer un développement moins rapide, en inventant aussi de nouveaux modes<br />

opérationnels d’intervention sur ces parcelles.<br />

JPPD : Réduire la disponibilité de sol pour contrôler la densité ? Pourtant en travaillant<br />

sur les cartes de cet ouvrage et en regardant les systèmes d’urbanisation holl<strong>and</strong>ais dans<br />

le détail, il se dégage une impression de régulation assez forte, comme vous le rappeliez<br />

à l’instant. Il y ainsi des villes qui ont, au cours des dernières décennies, développé<br />

leur urbanisation de manière équilibrée les unes par rapport aux autres : Amsterdam,<br />

Utrecht, Rotterdam.<br />

Il y a donc bien un outil de contrôle qui existe traditionnellement aux Pays-Bas. En Suisse,<br />

il n’y a pas tout à fait cet outil… Quant à la France, elle est encore à sa recherche, l’État<br />

ayant quelque peu disparu et les collectivités essayant d’inventer de nouvelles structures<br />

d’intervention territoriale.<br />

54

Interview with Kees Christiaanse<br />

The Dutch Model<br />

Jean-Pierre Pranlas-Descours [JPPD]: Let’s start by talking about scale, particularly that of<br />

the region. Is this the most appropriate scale for thinking about density? In this book we have<br />

focused on the Dutch example of the R<strong>and</strong>stadt <strong>and</strong> a particular l<strong>and</strong>scape of density in<br />

the province of Utrecht. Do you think that certain regions in the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s are well suited<br />

to the development of best practices? If so, then why? And finally, why do other countries<br />

in Europe have trouble with this type of construction?<br />

<strong>Territory</strong> I Interview<br />

Territoire I Entretien<br />

Kees Christiaanse [KC]: The Netherl<strong>and</strong>s is a real paradox! On the one h<strong>and</strong>, it is a small<br />

country with a lot of people—<strong>and</strong> where there are 1,300 inhabitants per square mile on<br />

average—while on the other h<strong>and</strong>, urban development is conceived of on a large scale.<br />

In that sense, the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s is very different from Belgium, Switzerl<strong>and</strong>, or Denmark,<br />

where l<strong>and</strong> use is much more fragmented, with smaller lot sizes that make urban<br />

development a lot harder. Historically, this particular situation emerged out of the need to<br />

manage the water on a collective level, which necessitated close collaboration <strong>and</strong> a distinct<br />

culture of civil engineering that was able to deal with large tracts of l<strong>and</strong> at once. Whether<br />

they belonged to the state, to the provinces, or to the municipalities, many areas were<br />

developed all in one go. That is why in the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s urban planning takes place on a<br />

larger scale than it does elsewhere <strong>and</strong> can also seem to happen more quickly. Sometimes<br />

though, we run the risk of building huge monofunctional neighborhoods that end up<br />

lacking diversity. The cultural horizon of sixty to eighty percent of the Dutch population is<br />

that of single-family dwelling home ownership. Such aspirations result in neighborhoods<br />

of low density.<br />

Of course, this suburban condition is common to many countries all over the world.<br />

For that reason, we often think of the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s as the “New Jersey of Europe.” The<br />

problem is that urbanization in the country is really easy because l<strong>and</strong> is cheap <strong>and</strong><br />

developers are not incentivized to create diverse or dense living spaces. In Switzerl<strong>and</strong><br />

the situation is very different—more than sixty percent of households rent their homes, <strong>and</strong><br />

there is a higher percentage of multi-level apartment buildings. Also the lot sizes are much<br />

smaller <strong>and</strong> property ownership is more fragmented. The issue of plot structure is essential.<br />

In the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s, we were able to create a system of artificial plot division in order to slow<br />

development, all the while inventing new practices of intervention on the parcels.<br />

JPPD: Are you saying that we should reduce the availability of l<strong>and</strong> in order to favor density?<br />

Yet when one examines the maps in this publication <strong>and</strong> the systems for Dutch<br />

urbanization, there seems to be a significant amount of regulation, which you’ve just<br />

mentioned. In the last few decades, a number of cities have chosen to urbanize in<br />

a relatively balanced way in relation to each other: Amsterdam, Utrecht, then Rotterdam.<br />

So it is clear that there is a traditional method of control in the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s. In Switzerl<strong>and</strong>,<br />

however, this instrument doesn’t exist… <strong>and</strong> in France we are looking for one now that the<br />

state has withdrawn <strong>and</strong> the regional <strong>and</strong> local authorities are seeking new forms<br />

of intervention.<br />

55

Entretien avec Kees Christiaanse<br />

<strong>Territory</strong> I Interview<br />

Territoire I Entretien<br />

Genève est aussi une ville qui souhaite s’étendre : il y a beaucoup de projets de densification,<br />

une ambition politique pour développer de 2 500 à 3 000 logements par an pendant vingt ans.<br />

Il y a une résistance très forte qui oppose systématiquement l’agriculture et la ville. Certes,<br />

on arrive à trouver d’autres localisations pour l’agriculture, mais on ne réfléchit jamais<br />

à la question de savoir comment inventer de nouveaux modèles de coexistence.<br />

KC : En Suisse, en Holl<strong>and</strong>e et en Allemagne, les surfaces agricoles sont encore assez proches<br />

de la ville centre. Mais je dois dire que je ne suis pas un admirateur de l’agriculture urbaine.<br />

Je n’y crois pas. Certes, l’économie fonctionne mais si l’on raisonne en termes de quantité<br />

productive, celle-ci est négligeable. Ce n’est donc pas un effort sérieux, car il ne se situe pas<br />

à l’échelle des discussions sur les surfaces réellement nécessaires. Prenons l’exemple<br />

de Singapour : on y produit les légumes dans des fermes verticales, mais le problème<br />

de cette forme d’agriculture est que l’on ne peut produire que des légumes verts, donc<br />

aucune nourriture de masse comme la pomme de terre, le riz et le blé. Toutefois, je pense<br />

que l’agriculture urbaine est utile à l’évolution des mentalités. Cela œuvre pour une forme<br />

d’interpénétration entre le paysage et la ville. C’est pour moi l’une des tâches les plus<br />

importantes pour les urbanistes d’aujourd’hui. De ce point de vue, l’exemple de la France<br />

est catastrophique : je pense aux gr<strong>and</strong>s centres commerciaux et les gr<strong>and</strong>es infrastructures<br />

qui leur sont associés, avec leurs dizaines de ronds-points. On s’approche même d’une situation<br />

dans laquelle la périphérie cannibalise l’intérieur des villes…<br />

Densité et mixité<br />

JPPD : Cela m’amène justement à la question des formes de la densité, qui pose également<br />

la question de la mixité… C’est un thème récurrent. Est-ce que la mixité est la condition<br />

de la densité ? Sur quelle forme de mixité peut-on réinterroger la densité ?<br />

KC : C’est une question d’échelle et de situation. On parle beaucoup des conditions de<br />

l’urbanité, et on observe que cette urbanité n’est pas le seul résultat de la mixité,<br />

mais plutôt d’une forme d’agrégation entre plusieurs petites unités monofonctionnelles.<br />

Ces confrontations produisent des configurations spatiales particulières, des situations<br />

d’interaction et de rencontre, qui encouragent cette condition urbaine de mixité et d’urbanité.<br />

Il est très important de souligner cela : la mixité, ce n’est pas simplement associer<br />

un maximum de fonctions, c’est l’association délicate de petites unités monofonctionnelles<br />

dans une configuration d’interaction. À Toronto par exemple, le quartier le plus vivant et<br />

urbain est Queen’s Street West. C’est un quartier qui s’est constitué au début du XX e siècle<br />

avec des maisons sur rue, des terrasses, un quartier majoritairement résidentiel. Finalement<br />

la mixité est parfois une sorte de mythe, même si lorsque l’on observe la banlieue parisienne,<br />

on se dit qu’il manque certaines interactions entre les différentes fonctions de la vie.<br />

JPPD : Le plus frappant, c’est que certains points de la périphérie sont parfois incroyablement<br />

intenses, comme en Seine-Saint-Denis (au nord de Paris), et qu’entre ces points il peut y avoir<br />

des zones de déshérence sociale et urbaine. C’est un phénomène que l’on observe dans<br />

beaucoup de métropoles du monde.<br />

60

Interview with Kees Christiaanse<br />

Middle Ages! Geneva is also a growing city, with densification projects <strong>and</strong> the political<br />

ambition to develop 2,500 to 3,000 housing units per year for the next twenty years. There<br />

is always a strong sense of resistance that pits agriculture against the city. Indeed, we can<br />

find other places for the location of agricultural activity, but we never think about how to<br />

invent new types of coexistence.<br />

<strong>Territory</strong> I Interview<br />

Territoire I Entretien<br />

KC: In Switzerl<strong>and</strong>, in the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> in Germany, agricultural l<strong>and</strong>s still remain close<br />

to the city center. But to tell you the truth, I am not really a fan of urban agriculture. I<br />

just don’t see it working. Of course, the economy of it is okay, but in terms of productive<br />

capacity there isn’t enough of an end result. So it’s more of a hobby than anything, because<br />

the surface areas aren’t big enough. Singapore is an example: they produce vegetables<br />

in vertical farms but the problem with that type of agriculture is that you can only ever<br />

produce green vegetables, not staple foods such as potatoes, rice, <strong>and</strong> wheat. Nonetheless,<br />

I do think that it is a useful practice in that it gets people thinking. It promotes integration<br />

between the countryside <strong>and</strong> the cityscape, which is in my opinion one of the most<br />

important things that urbanists should be thinking about today. In France, this is a real<br />

mess—there are strip malls with all the accompanying infrastructure, <strong>and</strong> all those traffic<br />

circles! We’ve almost reached the point where the periphery takes over the center.<br />

<strong>Density</strong> <strong>and</strong> Mixed-use Development<br />

JPPD: That brings me to the issue of morphology, which if we’re talking about density, also<br />

brings up the question of mixed-use development—it’s a recurring theme. Is mixed use a<br />

precursor for density? And what type of mixed use does density require?<br />

KC: That depends on both scale <strong>and</strong> situation. So what we’re talking about is urban living,<br />

<strong>and</strong> it becomes clear that the urban character isn’t directly the result of mixed use, but<br />

rather something like an aggregation of small monofunctional units. The confrontations<br />

that follow result in particular spatial configurations—the interactions <strong>and</strong> meetings<br />

encourage such an urban condition. Let me underline this important point: mixed-use<br />

development is not just about throwing a maximum number of functions together—it is<br />

about orchestrating the subtle associations between small homogenous units within a larger<br />

configuration of interactions. One example of this is the city of Toronto, in Canada, where<br />

the most lively <strong>and</strong> “urban” neighborhood is Queen Street West. The buildings date back to<br />

the beginning of the twentieth century: houses on the streets with front porches <strong>and</strong> back<br />

patios—it is an area that basically seems residential. In the end, mixed-use development is<br />

occasionally a myth, because even when we look at the Paris suburbs we can tell ourselves<br />

that they lack a certain number of interactions between lifestyle elements.<br />

JPPD: Definitely. The thing that really st<strong>and</strong>s out in that regard is the intensity of certain<br />

spaces in the periphery, such as Seine-Saint-Denis in the north of Paris. Between these<br />

nodes are areas of social <strong>and</strong> urban dormancy. This aspect is shared between many of the<br />

world’s metropoles.<br />

61

s u b u r b a n<br />

péri-urbain<br />

Bottière-Chênaie District in Nantes (FR)

Bottière-Chênaie District in Nantes (FR)<br />

Program I Suburban I Statement<br />

Programme I Péri-urbain I Constat<br />

Site <strong>and</strong> Location of the Bottière-Chênaie District<br />

At the beginning of the 1950s, the district of Doulon, which had been annexed by Nantes in 1908, still<br />

only consisted of vast expanses of market gardens with a peppering of housing estates <strong>and</strong> industrial or<br />

commercial lots whose uses were mostly linked to the railway boom—the district was indeed historically<br />

one of railway workers.<br />

Le site de Bottière-Chênaie<br />

Au début des années 1950, le quartier de Doulon (annexé à la ville de Nantes en 1908) n’est encore<br />

qu’un vaste espace maraîcher dans lequel se développent ça et là des lotissements et quelques<br />

activités, liées principalement à l’essor du chemin de fer – le quartier Doulon est historiquement celui<br />

des cheminots.<br />

81

POST-INDUSTRIAL<br />

post-industriel<br />

Havneholmen <strong>and</strong> Havnestad Districts, Sydhavnen in Copenhagen (DK)

Havneholmen <strong>and</strong> Havnestad Districts, Sydhavnen in Copenhagen (DK)<br />

Dybbølsbro<br />

Brygge Broen<br />

L<strong>and</strong>scape I Post-industrial I Territorial Link<br />

Paysage I Post-industriel I Lien territorial<br />

Amager<br />

Park<br />

Water as a Foundation for the Spatial Project: a New Relationship<br />

The redevelopment of the former harbor of Sydhavnen is more than just the straightforward but<br />

expensive decontamination of a brownfield site. It intends to radically transform part of the city <strong>and</strong><br />

to reactivate it by way of recreational activities, especially aquatic ones. To achieve this, the project<br />

redevelops <strong>and</strong> greatly increases the number of interfaces between the public space <strong>and</strong> the waterfront.<br />

New basins are built for marinas, the quays are transformed into linear parks, <strong>and</strong> the numerous floating<br />

swimming pools symbolize the reversal of the image <strong>and</strong> of the uses of the polluted industrial port.<br />

Transversal connections of soft mobility also open up the site at the metropolitan scale. A new walkway<br />

(Brygge Broen) connects the district to Amager Park, <strong>and</strong> a bicycle bridge (cycle slangen) passes through<br />

the docks <strong>and</strong> connects the intermodal hub of Dybbølsbro with the city center.<br />

Un nouveau rapport à l’eau comme fondement du projet territorial<br />

La reconquête de l’ancien port de Sydhavn ne peut se résumer à une simple et coûteuse opération<br />

de dépollution : elle vise la transformation radicale d’un morceau de ville et sa réactivation à travers<br />

le thème des loisirs, en particulier aquatiques. Pour cela le projet requalifie et multiplie les interfaces<br />

entre espace public et eau. De nouvelles darses sont destinées à des ports de plaisance, les quais sont<br />

transformés en parc linéaires et les nombreuses piscines flottantes symbolisent le renversement d’image<br />

et d’usage du port industriel pollué.<br />

117

Entretien avec Henri Bava<br />

qui s’invente. On a donc un espace où il faut sentir le moins possible la « patte »<br />

du paysagiste ou de l’urbaniste qui est intervenu. Je crois que cela ne pose aucun problème.<br />

De toute façon, les villes n’ont plus les moyens d’entretenir leurs espaces, surtout s’ils ont<br />

vocation à s’agr<strong>and</strong>ir. Encore une fois, il faut retrouver le fil conducteur : éviter que<br />

cet espace de liberté ne devienne le bastion fermé des uns ou des autres. L’importance est<br />

de créer des liens sur le long terme.<br />

JP : Un peu comme un urbaniste ?<br />

HB : Oui, c’est bizarre parce que lorsque j’ai commencé mon activité de paysagiste, on ne<br />

faisait rien comme des urbanistes : par exemple on commençait par la ville plutôt que par<br />

la voirie. En tant que paysagiste, on s’intéresse à ce que j’appellerais le « socle géographique »<br />

et, sur ce socle, on a des éléments construits. Paul Chemetov disait en regardant une carte<br />

de gr<strong>and</strong>e périphérie parisienne : « Bon, je vois bien des points, et des lignes, et je vois<br />

des gr<strong>and</strong>es surfaces blanches.» Les points sont des éléments construits, qui sont occupés<br />

par les architectes, et les lignes sont des infrastructures, car il y a aussi des ingénieurs.<br />

Mais qui va s’occuper de tous ces blancs ? Ces blancs, ce sont des socles géographiques.<br />

Il ne faut pas forcement s’en occuper en dessinant. Il ne s’agit pas de domestiquer mais<br />

de penser : comment construire, où construire, comment faire, comment placer, mais aussi<br />

comment ne pas construire et créer les espaces publics, comment trouver les lignes de force<br />

qui s’appuient sur des éléments qui devraient rester intangibles ? Et, à partir de là, laisser<br />

le plus de potentiel possible aux populations.<br />

Le paysage de la dédensification<br />

L<strong>and</strong>scape I Interview<br />

Paysage I Entretien<br />

JPPD : On observe aujourd’hui certains phénomènes de dédensifications flagrantes.<br />

Ces phénomènes ont toujours fonctionné dans l’histoire, par cycles de constructionab<strong>and</strong>on-reconstruction.<br />

Aujourd’hui on remarque que dans certaines régions, comme en<br />

ex-Allemagne de l’Est par exemple, plusieurs villes sont dans des périodes de dédensification :<br />

c’est notamment le cas des anciennes villes industrielles… On trouve aussi ce phénomène<br />

en Espagne : dans la gr<strong>and</strong>e banlieue de Madrid par exemple, on voit de gr<strong>and</strong>s quartiers<br />

neufs avec à peine 10% d’occupation… Quel impact tout cela a-t-il sur le paysage et sur<br />

le rapport au paysage ?<br />

HB : En Allemagne, c’est un nouveau modèle de paysage qui a été inventé dans la Ruhr :<br />

un paysage à la fois industriel et naturel, un paysage de reconquête végétale. Et les ruines<br />

industrielles conservées apparaissent un peu comme les folies des parcs anglais du XIX e<br />

siècle. Dans ce phénomène des « shrinking cities » (Schrumpfende Städte en allem<strong>and</strong>),<br />

je vois beaucoup d’opportunités pour repenser l’espace urbain, pour réintégrer l’agriculture,<br />

pour créer des jardins partagés ou réintroduire des boisements forestiers urbains. Il y a<br />

effectivement en Allemagne un courant qui valorise cette idée de dédensification. Je relie<br />

également ce processus à celui de la réutilisation du patrimoine. L’exemple des artistes<br />

de l’ex-Allemagne de l’Est qui investissent les gr<strong>and</strong>es barres de la période soviétique est<br />

intéressant. Ils ont en quelque sorte transformé ces bâtiments en vastes jardins verticaux.<br />

132

Interview with Henri Bava<br />

to be realized in the park, <strong>and</strong> they have been pivotal in igniting the spark of a vibrant<br />

neighborhood. Connected to the Seine River, it is a highly-planned park that manages both<br />

storm water <strong>and</strong> water runoff. It is also a civil engineering structure in that sense. In that<br />

project, we emphasized public use, <strong>and</strong> yes, design really does enable the use of public<br />

spaces. Nevertheless, when a l<strong>and</strong>scape becomes a place for “togetherness” more than<br />

anything else then we have to go back to the issue of design because we do not know how<br />

it came about. It’s the same trend as the “architecture without architects” that architects<br />

are experiencing. We are dealing with spaces where the influence of l<strong>and</strong>scape planners<br />

<strong>and</strong> urban planners must remain out of sight. I actually don’t think that that is a problem at<br />

all. In any case, cities do not have the funds to maintain public spaces, especially if they are<br />

set to exp<strong>and</strong>. Again, we must remember what the guiding principle is to maintain these<br />

places as spaces of freedom, <strong>and</strong> protecting them against being turned into community<br />

strongholds. So, we attempt to do just that. What is important is to cultivate lasting<br />

relationships <strong>and</strong> linkages.<br />

JPPD: … A bit like an urban planner, I suppose?<br />

HB: Well, indeed. It’s actually quite strange because when I started in l<strong>and</strong>scape design,<br />

we were very unlike urban planners. We’d start by addressing the cityscape rather than<br />

the street network. We l<strong>and</strong>scape planners take interest in what I’d call the “geographic<br />

substratum”—<strong>and</strong> it so happens that on this substratum are there constructed features.<br />

As he was facing a map of the outer periphery of Paris, Paul Chemetov is said to have<br />

remarked: “Well, I can see some dots, some lines, <strong>and</strong> also some large, white surfaces.”<br />

The “dots” are constructed features, the prerogative of architects, <strong>and</strong> the lines represent<br />

infrastructure, because there are also engineers. But who is going to take care of all these<br />

“blank spaces”? The “blanks” are geographic substrata. It is not absolutely necessary to<br />

draw something up in order to engage with them. It is not simply a case of domesticating<br />

these spaces but rather of thinking them through. How <strong>and</strong> where we should be building<br />

not only constructions but public spaces? Moreover, where <strong>and</strong> how shouldn’t we be<br />

building public spaces? Where can we find the intangible lines of force that make up<br />

the urban assemblage, <strong>and</strong> from there open up a maximum level of opportunities to its<br />

inhabitants?<br />

L<strong>and</strong>scape I Interview<br />

Paysage I Entretien<br />

“De-densified,” “Shrinking” L<strong>and</strong>scapes<br />

JPPD: In many places we are now seeing prominent instances of urban shrinkage. This is<br />

something that has always existed in history, settlements both wax <strong>and</strong> wane. These days,<br />

outmigration is happening in places such as in old industrial cities in former East Germany<br />

but also in Spain. In the outer suburbs of Madrid for instance, there are large, new districts<br />

that have occupancy rates of barely ten percent! What is the impact of this movement on<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>and</strong> to the human-l<strong>and</strong>scape relationship?<br />

HB: In Germany, a whole new model of l<strong>and</strong>scape was invented in the Ruhr region: both<br />

industrial <strong>and</strong> natural, it is a l<strong>and</strong>scape of triumphant vegetation. The preserved industrial<br />

ruins give a similar feel to the follies of eighteenth century gardens. I see many opportunities<br />

to rethink urban spaces in these shrinking cities (called Schrumpfende Städte in German),<br />

for instance by reinstating agriculture, creating communal gardens, <strong>and</strong> reintroducing urban<br />

forests. There is a current of thought in Germany that values de-densification. I relate this<br />

to the reuse of built heritage. The example of the artists from former East Germany who<br />

take over large, Soviet-style tower blocks is very interesting. In a way, they have managed to<br />

transform these buildings into vast vertical gardens.<br />

133

Bottière-Chênaie District in Nantes (FR)<br />

Housing I Suburban I Imbrication<br />

Habitat I Péri-urbain I Imbrication<br />

Pooling Urban Practices: Rising to the Challenge of the Periphery<br />

The founding strategy of the project was to combine different housing formats within the same<br />

operation. Six-storey collective buildings are developed next to intermediary <strong>and</strong> individual housing<br />

units stacked over two or three levels. These residential units share a number of common spaces:<br />

underground parking lots, gardens, <strong>and</strong> squares. In order to intersect the collective <strong>and</strong> the individual<br />

dimensions, the collective housing units have very wide loggias that are protected with a form of light<br />

blinds, which provide some intimacy to these external places <strong>and</strong> hence serve as a direct reference<br />

to individual housing.<br />

Mutualisation des pratiques urbaines : le défi de la périphérie<br />

L’association de plusieurs typologies de logements au sein d’une même opération constitue la stratégie<br />

fondatrice du projet. Ainsi, des bâtiments collectifs de six niveaux se développent en association avec<br />

des logements intermédiaires ou individuels groupés sur deux ou trois niveaux, tout en partageant<br />

des espaces communs : parkings enterrés, jardins, squares. Afin de croiser cette dimension collective et<br />

individuelle, les logements collectifs proposent des loggias de gr<strong>and</strong>e largeur protégées par des systèmes<br />

semi occultants, donnant une intimité à ces espaces extérieurs, référence directe à l’habitat individuel.<br />

150

Bottière-Chênaie District in Nantes (FR)<br />

Housing I Suburban I Perception<br />

Habitat I Péri-urbain I Perception<br />

151

îlot de l’Arc de Triomphe in Saintes (FR)<br />

Requirements – Conditions<br />

Housing – Habitat<br />

L<strong>and</strong>scape – Paysage<br />

Program – Programme<br />

<strong>Territory</strong> – Territoire

Project Process <strong>and</strong> Timeline<br />

The project by the architecture firm BNR provided an appropriate response to the deterioration of<br />

the historical center with its heritage approach targeting comfort <strong>and</strong> beautification. Beyond that, it called<br />

into question the relationship that residents have to the city center, given the urban <strong>and</strong> demographic<br />

dynamics that prevail at the scale of the extended city. This approach builds on general objectives that had<br />

been clearly established from the very outset by the municipality such as restoring the attractiveness<br />

of the center for certain categories of the population, including families with children. The diversity<br />

of typologies used (access to property, rented social housing, houses with gardens in the center of<br />

the block, <strong>and</strong> small collective units) makes it possible to renew the appropriation of the neighborhood<br />

whilst revealing its geographic <strong>and</strong> historical characteristics.<br />

Through its work on a single city block, BNR is, in fact, an entire urban project that draws on urban<br />

continuities between two overstretched cores—the Abbaye des Dames <strong>and</strong> the historical center on<br />

the Left Bank—by building on the enhancement of the alleyways, which makes up the unique character<br />

of the project. Through them, the heritage qualities of the urban fabric of this ancient suburban<br />

development are revealed. Furthermore, the large number of studies <strong>and</strong> the distribution of the project<br />

over several sites have brought about a series of operations addressing public spaces in its wake: the<br />

creation of a silo parking lot, a speed restriction zone, the enhancement of public places, <strong>and</strong> so on. All<br />

of these urban interventions demonstrate a profound change in uses <strong>and</strong> imagery in the city center.<br />

Le projet de l’agence d’architecture BNR n’apporte pas seulement une réponse de confort ou<br />

d’embellissement (patrimonialisation) à une situation de centre ancien dégradé : elle questionne aussi<br />

la manière d’habiter le centre, face aux dynamiques urbaines et démographiques à l’échelle<br />

de l’agglomération. Cette démarche s’appuie sur des objectifs d’ordre général clairement établis par<br />

la municipalité dès le départ, notamment redonner de l’attractivité au centre pour certaines catégories<br />

de population, dont les famille avec enfants. La diversité des typologies proposées (accession à<br />

la propriété, locatif social, maison avec jardin en cœur d’îlot, petit collectif) permet de renouveler<br />

l’appropriation du quartier en révélant ses caractéristiques géographiques et historiques.<br />

À partir du travail sur un îlot, BNR propose un projet urbain qui établit des continuités urbaines entre<br />

deux polarités distendues – l’Abbaye aux Dames et le centre historique rive gauche – en s’appuyant sur<br />

la mise en valeur des venelles, dispositif central du projet qui révèle les qualités patrimoniales du tissu<br />

urbain de ce faubourg. Enfin, la multiplication des études et la répartition du projet sur plusieurs sites<br />

entraînent dans leur sillage une série d’opérations parallèles et successives concernant l’espace public :<br />

création d’un parking silo, zone de circulation à vitesse réduite, mise en valeur des places publiques…<br />

Tout cela marque un véritable changement de dynamique d’usage et d’image pour le centre-ville.<br />

Architect: BNR Babled-Nouvet-Reynaud architectes, Laurent Berger SETEC TPI<br />

Client: SEMIS (Société d’économie Mixte de Saintonge)<br />

Project Sponsor, organizer of the participation in the EUROPAN competition:<br />

Municipality of Saintes<br />

Site: Îlot de l’Arc de Triomphe, Saintes, Charente-Maritime<br />

Program:<br />

64 housing units in 21 buildings, as follows:<br />

- 35 new units / 29 rehabilitated units<br />

- 38 rented social housing units / 26 units for private ownership<br />

- 53 units in collective housing / 11 individual units<br />

2 commercial premises, underground parking lot (30 spaces) <strong>and</strong> on-street parking <strong>and</strong> development<br />

of public spaces (alleyways)<br />

Site Area:<br />

Net floor area: 58,566 sq.ft. (5,441 m²) – Habitable space: 47,049 sq.ft. (4,371 m²)<br />

Total project perimeter: 64,648 sq.ft. (6,006 m²)<br />

Costs:<br />

Total costs (including external fixtures, alleyways <strong>and</strong> stone walls): 4,252,577 €<br />

which amounts to 90 € per sq.ft. of habitable floor area.<br />

Funding:<br />

For the urban project: SEMIS <strong>and</strong> French state (PUCA <strong>and</strong> DGUHC subsidies)<br />

For the housing units: SEMIS, City of Saintes (subsidies), French State (l<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> DAPA subsidy),<br />

Département of Charente-Maritime (subsidies), Caisse des dépôts et Consignation (PLA credit), sales<br />

revenue (transfer to private ownership).<br />

Key Dates:<br />

1988 Subst<strong>and</strong>ard Housing Clearance Act<br />

1993 BNR wins the europan competition<br />

2000 Demolition<br />

2005 Delivery<br />

Project Requirements <strong>and</strong> Process<br />

Les condition du projet et processus<br />

175

Havneholmen <strong>and</strong> Havnestad Districts, Sydhavnen in Copenhagen (DK)<br />

Le littoral de Copenhague, dans son contour comme dans son sol, est modelé par le développement<br />

de l’activité portuaire internationale de la ville au XIX e siècle. Aux portes de la ville, le site de Sydhavn<br />

se développe ainsi au début du XX e siècle à la jonction des nouvelles infrastructures de transports<br />

terrestre et maritime. Au lendemain de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, un projet territorial à l’échelle<br />

du gr<strong>and</strong> Copenhague, le Finger Plan, structure l’accroissement de l’activité portuaire et essaie de<br />

canaliser l’urbanisation accélérée de la capitale pendant la seconde moitié du XX e siècle. À partir des<br />

années 1980, les mutations industrielles qui libèrent de larges emprises foncières confirment la nécessité<br />

de penser la reconversion des friches portuaires à l’échelle de la métropole et son identité en devenir.<br />

En 1992, le renforcement de la gouvernance métropolitaine de Copenhague s’accompagne<br />

d’une planification à l’échelle transfrontalière liant le développement de Copenhague à celui de Malmö<br />

en Suède. De nouvelles structures publiques d’aménagement puissantes permettent de faire converger<br />

les investissements tant publics que privés afin d’inciter les entreprises et les jeunes foyers à rester en ville.<br />

La nécessité d’une entreprise de dépollution de Sydhavn pour envisager sa reconversion engage la ville<br />

dans un chantier à gr<strong>and</strong>e échelle en réorganisant son système d’assainissement et en fondant<br />

une nouvelle identité avec un nouveau rapport de la ville à l’eau.<br />

Nouveau doigt « aquatique » du Finger Plan, le site participe au développement d’un axe programmatique et<br />

spatial qui décline nouveaux habitats, nouvelles infrastructures, construction d’équipements,reconversion<br />

de bâtiments industriels et de sites militaires autour du thème « vivre et habiter au bord de l’eau ».<br />

184

Project Process <strong>and</strong> Timeline<br />

Sydhavnen in Copenhagen (DK)—Post-Industrial<br />

The Copenhagen waterfront is modeled by the development of the international harbor of the Danish<br />

capital during the nineteeth century. Located at the gates of the city <strong>and</strong> at the crossroads between new<br />

road <strong>and</strong> port infrastructure, the site of Sydhavnen followed suit in the twentieth century. Following the<br />

Second World War, the so-called “Finger Plan”—large-scale spatial planning at the scale of the Greater<br />

Copenhagen—was designed both to support the increase of port activities <strong>and</strong> to channel the accelerated<br />

urbanization during the second half of the twentieth century. After the 1980s, industrial change brought<br />

about the release of large tracts of l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> confirmed the need to plan for the reconversion of the<br />

harborside industrial brownfield sites at the scale of the conurbation <strong>and</strong> to define its emergent identity.<br />

In 1992, the reinforcement of the metropolitan governance of Copenhagen went h<strong>and</strong> in h<strong>and</strong> with<br />

large-scale transborder spatial planning initiative that linked the development of Copenhagen to that<br />

of Malmö in Sweden. New <strong>and</strong> powerful public spatial planning entities were set up in order to bring<br />

about the convergence of public <strong>and</strong> private investment <strong>and</strong> to induce companies <strong>and</strong> young families<br />

to stay in town. Decontamination was a prerequisite to the reconversion of Sydhavnen. For that<br />

reason, the city became engaged in large-scale public works <strong>and</strong> reorganized its sewage system. It<br />

emerged with a new identity <strong>and</strong> a new relationship to its waterfront. Sydhavnen is the new “aquatic”<br />

finger in the Finger Plan. It is a part of a new programmatic <strong>and</strong> spatial pillar that involves new<br />

housing formats, new infrastructure, new amenities, <strong>and</strong> the reconversion of industrial buildings <strong>and</strong><br />

military sites under the theme of “living on the waterfont.”<br />

Project Requirements <strong>and</strong> Process<br />

Les condition du projet et processus<br />

185

Biographies<br />

Jean-Pierre PRANLAS-DESCOURS<br />

Architect <strong>and</strong> urban planner—www.pdaa.eu<br />

Having graduated from France’s école d’<strong>Architecture</strong> de Versailles in 1982 <strong>and</strong> the école<br />

des Hautes études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) in 1984, Jean-Pierre became a laureate<br />

of the Academy of France in Rome <strong>and</strong> spent two years in residency at the Villa Medicis,<br />

between 1986 <strong>and</strong> 1988. An expert in architecture, design, <strong>and</strong> urban <strong>and</strong> regional<br />

planning, he founded the firm Pranlas-Descours Architecte Associés, <strong>and</strong> has taught at the<br />

école Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées. Since 2004 he has been a professor at the école<br />

Nationale d’<strong>Architecture</strong> de Paris-Malauqais <strong>and</strong> has curated several exhibitions, including<br />

the 2003 Archipel métropolitain, territoires partagés, which was the first exhibition entirely<br />

devoted to the Parisian metropolis.<br />

Architecte et urbaniste — www.pdaa.eu<br />

Diplômé de l’école d’<strong>Architecture</strong> de Versailles en 1982 et de l’EHESS en 1984, il a été lauréat<br />

du concours de l’Académie de France à Rome et pensionnaire de la Villa Médicis entre 1986<br />

et 1988. Il exerce son activité dans le domaine architectural, du design, des projets urbains<br />

et territoriaux. Il est le fondateur de Pranlas-Descours Architecte Associés. Il a enseigné à<br />

l’école Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées et il est professeur à l’école Nationale d’<strong>Architecture</strong><br />

de Paris-Malaquais depuis 2004. Il a été commissaire de nombreuses expositions,<br />

dont en 2003 L’Archipel métropolitain, territoires partagés, première exposition consacrée<br />

à la métropole parisienne.<br />

Kees CHRISTIAANSE<br />

Architect <strong>and</strong> urban planner—www.kcap.eu<br />

With a degree from TU Delft in the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s, Kees Christiaanse worked for the OMA<br />

architecture firm from 1980 to 1989 before opening his own practice, Kees Christiaanse<br />

Architects & Planners (KCAP). Their offices were first in Rotterdam, then were extended<br />

to Zurich (in 2006), <strong>and</strong> to Shanghai (in 2011). Kees Christiaanse has curated several<br />

exhibitions, including the Rotterdam <strong>Architecture</strong> Biennial in 2009, <strong>and</strong> taught courses in<br />

architecture <strong>and</strong> urban planning at TU Berlin from 1996 to 2003, <strong>and</strong> at ETH in Zurich.<br />

Architecte et urbaniste — www.kcap.eu<br />

Diplômé de la TU Delft, Kees Christiaanse travaille d’abord au sein de l’agence OMA de 1980<br />

à 1989. Il créé ensuite sa propre structure Kees Christiaanse Architects & Planners (KCAP)<br />

en 1989 à Rotterdam puis ouvre de nouveaux bureaux à Zurich (2006) et à Shanghai (2011).<br />

Il a été commissaire de nombreuses expositions, notamment de la Biennale internationale<br />

d’<strong>Architecture</strong> de Rotterdam en 2009. Il a enseigné l’architecture et l’urbanisme à la TU<br />

Berlin de 1996 à 2003, puis il est professeur à l’ETH de Zurich depuis 2003.<br />

Marc ARMENGAUD<br />

Philosopher—www.awp.fr<br />

In 1994, Marc Armengaud earned his DEA (Diplome d’Etudes Approfondies) in<br />

Philosophy, <strong>and</strong> in 2003, partnered with two associates to found the firm AWP, Agence de<br />

Reconfiguration Territoriale. His role in the firm is to conduct research <strong>and</strong> experimentation,<br />

<strong>and</strong> has included curating, particularly the 2013 Paris la Nuit exhibition at Pavillon de<br />

l’Arsenal. A regular contributor to the Revue d’<strong>Architecture</strong>, he has been a professor at the<br />

école Nationale Supérieure d’<strong>Architecture</strong> Paris-Malaquais since 2009.<br />

194

Biographies<br />

Philosophe — www.awp.fr<br />

Titulaire d’un DEA (Diplôme d’études Approfondies) en philosophie en 1994, Marc Armengaud<br />

fonde avec deux associés AWP, Agence de Reconfiguration Territoriale, en 2003. Il dirige<br />

au sein de l’agence les projets de recherche, d’expérimentation et de commissariat, dont<br />

l’exposition Paris la Nuit au Pavillon de l’Arsenal (2013). Collaborateur régulier de la revue<br />

D’<strong>Architecture</strong>, il enseigne à l’école Nationale Supérieure d’<strong>Architecture</strong> Paris-Malaquais<br />

depuis 2009.<br />

Henri BAVA<br />

L<strong>and</strong>scape architect—www.agenceter.com<br />

After having been awarded a degree from the école Nationale Supérieure de Paysage de<br />

Versailles in 1984, Henri Bava founded Agence Ter with two associates in 1986. Then from<br />

1996 to 1998, he was president of the Féderation Française du Paysage, <strong>and</strong> in 2007 he<br />

received France’s Gr<strong>and</strong> Prix National du Paysage. Henri Bava has been a professor at the<br />

faculty of <strong>Architecture</strong> in Karlsruhe in Germany since 1998, <strong>and</strong> a guest professor at Harvard<br />

Graduate School of Design since 2011.<br />

Paysagiste — www.agenceter.com<br />

Diplômé de l’école Nationale Supérieure de Paysage de Versailles en 1984, Henri Bava fonde<br />

l’Agence Ter avec deux associés en 1986. Il est président de la Fédération française du paysage<br />

de 1996 à 1998 et reçoit le Gr<strong>and</strong> Prix National du Paysage en 2007. Henri Bava est<br />

professeur à la faculté d’architecture de Karlsruhe en Allemagne depuis 1998 et professeur<br />

invité à la Harvard Graduate School of Design depuis 2011.<br />

Alain SALLEZ<br />

Economist<br />

With a degree from ESSEC Business School in 1961, Alain earned his doctorate in Economy<br />

<strong>and</strong> Business Administration in 1970 (from the Faculté de Droit et des Sciences Economiques<br />

de Paris I), <strong>and</strong> was awarded an Eisenhower Foundation fellowship in 1971. As a specialist<br />

in urban economy <strong>and</strong> regional development, Alain Sallez is an honorary professor at ESSEC<br />

<strong>and</strong> has been a professor at the école nationale des ponts et chaussées. He is the director<br />

of the Institute des Villes, du Territoire et de l’Immobilier, chairman of the urban planning<br />

branch of the national scientific committee (CNRS), <strong>and</strong> an international expert for the<br />

United Nations.<br />

économiste<br />

Diplômé de l’ESSEC en 1961, Alain Sallez est Docteur en économie et administration des<br />

entreprises en 1970 (Faculté de Droit et des Sciences économiques de Paris I) et titulaire<br />

de l’Eisenhower Foundation fellowship en 1971. Spécialiste en économie urbaine et<br />

en développement régional, il est aujourd’hui professeur honoraire à l’ESSEC et a été<br />

professeur à l’école nationale des ponts et chaussées. Il est directeur de l’Institut des Villes,<br />

du Territoire et de l’Immobilier, chairman du comité scientifique de la recherche urbaine<br />

(CNRS) et expert international auprès des Nations Unies.<br />

195