I templi preistorici di Stonehenge e Avebury - The preistoric temples ...

I templi preistorici di Stonehenge e Avebury - The preistoric temples ...

I templi preistorici di Stonehenge e Avebury - The preistoric temples ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

I <strong>templi</strong><br />

<strong><strong>preistoric</strong>i</strong> <strong>di</strong><br />

<strong>Stonehenge</strong><br />

e <strong>Avebury</strong><br />

a cura <strong>di</strong> /by Dr Daniele Vilasco<br />

<strong>The</strong> prehistoric<br />

<strong>temples</strong> of<br />

<strong>Stonehenge</strong><br />

and <strong>Avebury</strong>

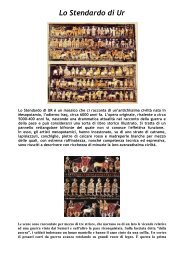

Piantina <strong>di</strong> <strong>Stonehenge</strong> con le varie fasi costruttive C’è stato un tempo, millenni fa, in cui il<br />

nostro continente era un’unica grande<br />

realtà, dalle coste atlantiche a quelle<br />

del Mar Nero. Di quella che fu la prima Europa<br />

unita restano gigantesche testimonianze <strong>di</strong><br />

pietra, i famosi monumenti megalitici che da<br />

allora non hanno mai smesso <strong>di</strong> colpire la fantasia<br />

degli uomini. Queste possenti strutture<br />

cominciarono ad essere erette a partire dal<br />

4500 a.C. lungo una larga fascia che comprende<br />

isole britanniche, Olanda, Danimarca e<br />

Germania del nord, penisola iberica, Francia,<br />

Italia, Bulgaria e Georgia.<br />

Tutta quest’area presenta numerose attestazioni<br />

<strong>di</strong> camere funerarie realizzate con gran<strong>di</strong><br />

blocchi <strong>di</strong> pietra coperti da lastroni (dolmen),<br />

pietre infisse verticalmente nel terreno, da<br />

sole o in lunghe file (menhir) e circoli <strong>di</strong> pietre<br />

all’interno dei quali si svolgevano riti religiosi<br />

(cromlech).<br />

Plan of <strong>Stonehenge</strong> with the various stages of construction Costruiti in quelli che ai nostri occhi appaiono<br />

come luoghi cupi e solitari, ingran<strong>di</strong>ti e risistemati<br />

più volte, questi monumenti vennero realizzati secondo rituali e scopi che restano<br />

ignoti e misteriosi. Alcuni <strong>di</strong> essi tuttavia fanno chiaramente riferimento a fenomeni<br />

legati al ciclo delle stagioni, nonché al sorgere e al tramontare del Sole, della Luna<br />

e anche <strong>di</strong> importanti stelle e costellazioni.<br />

Per le popolazioni <strong>preistoric</strong>he del tempo, ancora <strong>di</strong>vise tra una ru<strong>di</strong>mentale agricoltura<br />

e l’abituale allevamento e perciò semi-noma<strong>di</strong>, questi giganti <strong>di</strong> pietra furono in<strong>di</strong>spensabili<br />

punti <strong>di</strong> riferimento sul territorio e importanti segnali, per sé e per le altre<br />

tribù, della progressiva conquista <strong>di</strong> quel mondo ignoto e selvaggio che fino ad allora<br />

era stato l’Europa.<br />

I due più importanti <strong>templi</strong> <strong><strong>preistoric</strong>i</strong> della Gran Bretagna, <strong>Stonehenge</strong> e <strong>Avebury</strong>,<br />

sorgono ad esempio ad una <strong>di</strong>stanza relativamente breve l’uno dall’altro, solo ventotto<br />

chilometri, in quella ridente regione del sud dell’Inghilterra che è la pianura intorno<br />

a Salisbury, un paesaggio verdeggiante appena movimentato da piccole colline gessose.<br />

Durante il neolitico la zona fu il fulcro <strong>di</strong> un vasto reticolo <strong>di</strong> vie commerciali, le<br />

quali convergevano qui attraverso i crinali privi <strong>di</strong> boschi che ancora attraversano<br />

tutta l’Inghilterra meri<strong>di</strong>onale. Grazie ad essi si potevano infatti evitare le numerose<br />

valli paludose e impercorribili che allora solcavano l’Isola e lungo il loro percorso sono<br />

state rinvenute numerose testimonianze <strong>di</strong> commerci <strong>di</strong> lunga <strong>di</strong>stanza, chiara testimonianza<br />

della loro importanza per le popolazioni primitive del tempo.<br />

Merci e uomini si spostavano soprattutto lungo la famosa Harroway, la via che da<br />

Dover giungeva fino a <strong>Stonehenge</strong>. Allora come oggi, lo stretto <strong>di</strong> Dover era infatti la<br />

principale porta d’accesso all’isola dal continente, il che permette <strong>di</strong> capire più <strong>di</strong> ogni<br />

altro dato quale dovesse essere l’importanza del grande tempio astronomico <strong>di</strong><br />

Vista da est, <strong>Stonehenge</strong> si staglia contro<br />

il cielo del tramonto<br />

Seen from the east, <strong>Stonehenge</strong> stands out<br />

against the sunset sky<br />

<strong>Stonehenge</strong>, posto al termine della più vitale<br />

tra le “piste” commerciali dell’Inghilterra<br />

<strong>preistoric</strong>a. La <strong>Stonehenge</strong> attuale è il frutto<br />

del progressivo accumulo <strong>di</strong> fasi costruttive<br />

<strong>di</strong>verse, in una lunga sovrapposizione cominciata<br />

a partire dal 3000 a.C. circa.<br />

A questa data risalgono infatti il fossato circolare<br />

e l’argine, all’interno dei quali dovevano<br />

probabilmente esistere alcune strutture in<br />

legno, realizzate con pali.<br />

Così sembrerebbe in<strong>di</strong>care la scoperta, appena<br />

all’interno del terrapieno, <strong>di</strong> ben 56 buche<br />

<strong>di</strong> palo <strong>di</strong>sposte a formare un grande circolo.<br />

Esisteva un unico ingresso al complesso,<br />

costituito da un viale orientato verso nord-est,<br />

ovverosia lungo l’asse del tramonto nel solstizio<br />

d’inverno e dell’alba nel solstizio d’estate.<br />

Fu già in questa prima fase che la famosa<br />

Heel Stone, pesante ben trentacinque tonnellate,<br />

ed una seconda pietra, ora scomparsa

<strong>The</strong>re was a time, thousands of years ago, when our continent was a single<br />

great unit, from the Atlantic to the Black Sea coasts. Of what was the first<br />

United Europe there remain gigantic records in stone, the famous megalithic<br />

monuments which have never ceased to strike people’s imagination ever since.<br />

Erection of these imposing structures began from 4,500 BC onwards, along a wide<br />

band taking in the British Isles, Holland, Denmark and North Germany, the Iberian<br />

peninsula, France, Italy, Bulgaria and Georgia. All this area presents numerous<br />

examples of burial chambers made up of large stone blocks covered by slabs<br />

(dolmens), stones fixed vertically in the ground, alone or in long rows (menhirs) and<br />

stone circles within which religious rites were held (cromlechs).<br />

Built in what appear to our eyes as bleak, solitary sites, enlarged and rearranged<br />

several times, these monuments were created accor<strong>di</strong>ng to rituals and purposes that<br />

remain unknown and mysterious. Some of them, however, make a clear reference to<br />

phenomena relating to the cycle of the seasons, as well as the rising and setting of the<br />

Sun, the Moon and important stars and constellations.<br />

For the prehistoric peoples of the time, still <strong>di</strong>vided between ru<strong>di</strong>mentary agriculture<br />

and bree<strong>di</strong>ng of livestock, and therefore seminoma<strong>di</strong>c, these stone giants were in<strong>di</strong>spensable<br />

reference points on the land and important signs, for themselves and other<br />

tribes, of the gradual conquest of that unknown, wild world that Europe had been until<br />

then. <strong>The</strong> two most important prehistoric <strong>temples</strong> in Great Britain - <strong>Stonehenge</strong> and<br />

<strong>Avebury</strong> - stand a relatively short <strong>di</strong>stance<br />

apart, only twenty-eight kilometres, in that<br />

<strong>Stonehenge</strong> come appare oggi<br />

pleasant region of southern England known<br />

as Salisbury plain, a verdant countryside only<br />

just enlivened by small chalky hills.<br />

During the Neolithic age the area was the hub<br />

of a vast network of trade routes, which<br />

converged there along the unwooded ridges<br />

which still cross the whole of southern<br />

England. Thanks to these it was possible to<br />

avoid the many marshy, impassable valleys<br />

which ran across the island at that time and<br />

numerous records of long <strong>di</strong>stance trade have<br />

been found along their routes, as a clear<br />

witness to their importance to the primitive<br />

peoples of the time. Merchan<strong>di</strong>se and men<br />

moved especially along the famous Harroway,<br />

the road from Dover to <strong>Stonehenge</strong>.<br />

<strong>Stonehenge</strong> as it appears today<br />

<strong>The</strong>n as now, the strait of Dover was the main<br />

port of access to the island from the continent,<br />

which more than any other fact enables us to understand what must have been the<br />

importance of the great astronomical temple of <strong>Stonehenge</strong>, stan<strong>di</strong>ng at the end of the<br />

most vital trade route in prehistoric England.<br />

Present-day <strong>Stonehenge</strong> is the result of the gradual accumulation of <strong>di</strong>fferent stages of<br />

buil<strong>di</strong>ng, in a long superimposition which began from about 3000 BC.<br />

<strong>The</strong> circular <strong>di</strong>tch and the embankment date from those times and within these there<br />

were probably wooden structures built with stakes. This would seem to be in<strong>di</strong>cated by<br />

the structure, just inside the embankment, of as many as 56 stake holes arranged in a<br />

large circle. <strong>The</strong>re was a single entrance to the complex, consisting of an avenue<br />

running north-east, along the axis between sunset in the winter solstice and dawn in<br />

the summer solstice. Already at this early stage the famous Heel Stone, weighing no<br />

less than thirty-five tonnes, and a second stone which has <strong>di</strong>sappeared but was probably<br />

similar to the first, were laid at the sides of the sanctuary entrance, making it a<br />

monumental entrance. Probably the area within the three concentric circles formed by<br />

the <strong>di</strong>tch, the embankment and the circle of stakes was left free for the hol<strong>di</strong>ng of<br />

ceremonies of which we unfortunately know nothing. At a certain point, for reasons<br />

unknown to us, the area was abandoned, judging by the fin<strong>di</strong>ng of a large number of<br />

DIAMANTE Applicazioni & Tecnologia<br />

31

ma con ogni probabilità uguale alla prima, vennero infisse ai lati dell’ingresso del<br />

santuario, in modo da costituirne un ingresso monumentale.<br />

Probabilmente l’area all’interno dei tre cerchi concentrici formati dal fossato, dal<br />

terrapieno e dal cerchio <strong>di</strong> pali venne lasciata libera per lo svolgimento <strong>di</strong> cerimonie <strong>di</strong><br />

cui sfortunatamente non conosciamo nulla. Ad un certo punto, per cause che non<br />

conosciamo, l’area venne abbandonata, stando a quanto ci racconta il rinvenimento <strong>di</strong><br />

abbondanti gusci <strong>di</strong> lumache chiamate Zonitidae, abituali frequentatrici <strong>di</strong> prati incolti,<br />

non utilizzati neppure per il pascolo. Il monumento continuò ad essere usato esclusivamente<br />

come cimitero, come testimoniano le circa trenta cremazioni rinvenute nell’area<br />

delle buche <strong>di</strong> palo; in tutta la zona intorno ad esso inoltre cessò qualsiasi<br />

forma <strong>di</strong> agricoltura e <strong>di</strong> allevamento.<br />

La forza evocativa del luogo e dei suoi culti comunque sopravvisse all’oblio, dal<br />

momento che, con l’arrivo <strong>di</strong> nuove popolazioni, definite popolo delle Coppe, i culti<br />

nel santuario ripresero vigore. Questi nuovi abitanti,<br />

originari della valle del Reno, nell’o<strong>di</strong>erna<br />

Germania, giunsero in Inghilterra tra il 2500 e il<br />

2200 a.C., a seguito <strong>di</strong> un vero e proprio fenomeno<br />

<strong>di</strong> colonizzazione, in cerca <strong>di</strong> nuove terre da<br />

coltivare e <strong>di</strong> materiali rameosi.<br />

Con la loro venuta gli archeologi fanno tra<strong>di</strong>zionalmente<br />

iniziare l’Età del Bronzo sull’Isola.<br />

A partire dal 2100 a.C. <strong>Stonehenge</strong> conobbe<br />

quin<strong>di</strong> una nuova fase costruttiva, durante la<br />

quale il suo orientamento a nord-est venne fortemente<br />

enfatizzato dalla monumentalizzazione del<br />

Viale, che venne affiancato sui due lati da due<br />

argini, con relative trincee esterne, lunghi oltre<br />

cinquecento metri. L’ingresso stesso venne allargato<br />

e tutto il monumento venne riallineato<br />

secondo un asse spostato leggermente più a est,<br />

ovverosia a cinquanta gra<strong>di</strong> rispetto ai precedenti<br />

quarantuno. Lungo il grande argine circolare vennero<br />

infisse le quattro Pietre <strong>di</strong> Riferimento<br />

(Station Stones), le quali costituirono i vertici <strong>di</strong><br />

un rettangolo ideale che racchiudeva la vasta<br />

area centrale e appariva orientato secondo una<br />

complessa serie <strong>di</strong> dati astronomici.<br />

Stando alla ricostruzione attuale, infatti, i lati<br />

corti, paralleli al Viale e alla Heel Stone, erano<br />

orientati verso il punto in cui sorge il Sole durante<br />

il Solstizio d’Estate, mentre i lati lunghi trovavano<br />

la loro origine nelle posizioni estreme toccate<br />

dalla Luna al solstizio d’estate e a quello d’inverno.<br />

La sacralità <strong>di</strong> questo orientamento venne<br />

sancita dalla realizzazione, intorno a ciascuna<br />

delle quattro Pietre, <strong>di</strong> un argine e della corrispondente<br />

fossa circolare, chiaro segno della<br />

volontà <strong>di</strong> preservarle e isolarle all’interno del<br />

monumento. Fu in questo momento inoltre che<br />

comparvero per la prima volta le famose Pietre<br />

Azzurre, utilizzate per due modesti cerchi posti al centro del complesso, ciascuno dei<br />

quali con l’ingresso volto, ancora una volta, al Viale. Con ogni probabilità fu poi proprio<br />

in quest’epoca che venne tracciata la strada che collegava il santuario al fiume<br />

Avon, penultima tappa del lunghissimo viaggio, ben 360 chilometri, che le Blue<br />

Stones compivano dal Monte Prescelly fino a <strong>Stonehenge</strong>.<br />

Tuttavia solo a partire dal 2000-1900 a.C. <strong>Stonehenge</strong> assunse l’aspetto che ancora<br />

oggi colpisce con tanta forza la nostra immaginazione. Nell’arco <strong>di</strong> circa quattrocento<br />

anni il santuario <strong>di</strong>venne infatti una vera e propria selva <strong>di</strong> monoliti variamente <strong>di</strong>sposti<br />

e collegati tra loro, ancora una volta secondo uno schema circolare fortemente<br />

legato a complessi calcoli astronomici.<br />

Ad una prima fase risalgono non solo il famosissimo Ferro <strong>di</strong> Cavallo, composto da<br />

cinque coppie <strong>di</strong> giganteschi triliti, ma anche il cerchio <strong>di</strong> blocchi <strong>di</strong> arenaria collegati<br />

da architravi monolitici, chiamato Circolo Sarsen, che lo circonda. Le pietre con cui<br />

quest’ultimo venne realizzato provenivano a loro volta da lontano, dalle alture nei<br />

pressi <strong>di</strong> <strong>Avebury</strong>, a circa trentadue chilometri <strong>di</strong> <strong>di</strong>stanza.<br />

Il Ferro <strong>di</strong> Cavallo. Sulla sinistra, quanto rimane del trilite centrale, sormontato dal tenone.<br />

L’architrave abbattuta, <strong>di</strong> cui sono visibili le due mortase, giace davanti ad esso<br />

<strong>The</strong> Horseshoe. On the left, what remains of the central trilithon, surmounted by<br />

the tenon. <strong>The</strong> fallen architrave, with the two mortises visible, lies in front of them

shells of snails known as Zoniti<strong>di</strong>ae, which<br />

habitually frequent uncultivated areas not<br />

even used as pasture.<br />

<strong>The</strong> monument continued to be used<br />

exclusively as a cemetery, as witnessed by<br />

the thirty or so cremations <strong>di</strong>scovered in the<br />

area of the stake-holes. In ad<strong>di</strong>tion, all forms<br />

of agriculture and her<strong>di</strong>ng ceased throughout<br />

the surroun<strong>di</strong>ng area. However, the evocative<br />

force of the site and its cults survived oblivion<br />

because with the arrival of new peoples,<br />

known as the Bowls people, worship in the<br />

holy place revived.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se new inhabitants, originating from the<br />

Rhine valley in modern Germany, arrived in<br />

England between 2500 and 2200 BC, in a<br />

wave of colonization, looking for new land to<br />

cultivate and copper ores.<br />

Archaeologists tra<strong>di</strong>tionally date the Bronze<br />

Age in the island from their arrival.<br />

From 2100 BC onward <strong>Stonehenge</strong> thus saw a new phase of buil<strong>di</strong>ng, during which its<br />

north-east orientation was strongly emphasised by the monumentalization of the<br />

Avenue, which was flanked by two embankments, with relating external trenches, over<br />

five hundred metres long. <strong>The</strong> entrance itself was widened and the whole monument<br />

was realigned along an axis slightly more easterly in <strong>di</strong>rection, at 50° rather than the<br />

previous 41°. <strong>The</strong> four reference Station Stones were placed along the large circular<br />

embankment, forming the corners of an ideal rectangle which took in the wide central<br />

area and seems to have been oriented accor<strong>di</strong>ng to a complex series of astronomical<br />

data. Going by the present structure, the short sides, parallel to the Avenue and the<br />

Heel Stone, were oriented towards the point where the sun rises during the Summer<br />

Solstice, while the long sides had their origin in the extreme positions touched by the<br />

moon at the summer and winter solstices.<br />

<strong>The</strong> sacred nature of this orientation was sanctioned by the creation around each of<br />

the four Stones of an embankment with a correspon<strong>di</strong>ng circular trench, a clear sign of<br />

the desire to preserve them and isolate them within the monument. It was also at this<br />

time that the famous Blue Stones first appeared, used for two modest circles at the<br />

centre of the complex, each having its entrance once again facing the Avenue.<br />

In all probability it was precisely in this period that the road connecting the holy place<br />

to the river Avon was traced, the next to last<br />

stage of the very long 360-kilometres journey<br />

made by the Blue Stones from Mount<br />

Prescelly to <strong>Stonehenge</strong>.<br />

However, it was only from 2000-1900 BC that<br />

<strong>Stonehenge</strong> took on the appearance that still<br />

strikes our imagination so much today.<br />

Over about four hundred years the site<br />

became a forest of monoliths, variously arranged<br />

and connected, once again accor<strong>di</strong>ng to a<br />

circular scheme closely linked to complex<br />

astronomical calculations.<br />

From the first stage date not only the famous<br />

Horseshoe, made up of five pairs of gigantic<br />

trilithons, but also the circle of sandstone<br />

blocks connected by monolithic architraves,<br />

known as the Sarsen Circle, which surrounds<br />

it. <strong>The</strong> stones with which the latter was built<br />

came in turn from a long <strong>di</strong>stance, from the<br />

Tre pietre ancora in situ del Circolo Sarsen<br />

Three stones of the Sarsen Circle still in situ<br />

Veduta del Circolo Sarsen e delle Pietre Azzurre, molto più piccole,<br />

poste al suo interno<br />

View of the Sarsen Circle with the much smaller Blue Stones inside it<br />

DIAMANTE Applicazioni & Tecnologia<br />

33

Pianta <strong>di</strong> <strong>Avebury</strong><br />

Map of <strong>Avebury</strong><br />

Questo cerchio <strong>di</strong> arenarie, con la sua curva<br />

regolare e la perfezione degli incastri<br />

maschio-femmina che collegano architravi e<br />

pilastri nonostante la pendenza del terreno,<br />

non smette <strong>di</strong> stupire gli osservatori moderni<br />

e mostra con chiarezza estrema le incre<strong>di</strong>bili<br />

capacità tecniche raggiunte dalle<br />

popolazioni dell’Età del Bronzo.<br />

Intorno al 1550 a.C. il complesso conobbe<br />

ulteriori mo<strong>di</strong>fiche, per molti versi ancora<br />

misteriose. Innanzi tutto, una selva <strong>di</strong> pali<br />

lignei, <strong>di</strong>sposti su due cerchi concentrici,<br />

venne impiantata all’esterno del Circolo<br />

Sarsen: <strong>di</strong> essa rimangono solo le tracce<br />

delle numerosissime buche <strong>di</strong> palo, definite<br />

dagli archeologi come Cerchio Z e Cerchio Y.<br />

Inoltre le Pietre Azzurre impiantate nel<br />

periodo precedente vennero estratte dalle<br />

loro se<strong>di</strong> e risistemate, in armonia con i<br />

massi usati per il Circolo Sarsen, a formare<br />

un ovale all’interno del Ferro <strong>di</strong> Cavallo.<br />

Poco tempo dopo la <strong>di</strong>sposizione delle Blue<br />

Stones venne <strong>di</strong> nuovo mo<strong>di</strong>ficata e le<br />

pietre andarono a formare due <strong>di</strong>stinti raggruppamenti, un piccolo ferro <strong>di</strong> cavallo<br />

all’interno dell’omonimo e ben più imponente insieme <strong>di</strong> triliti e un nuovo ovale posto<br />

tra quest’ultimo e il Circolo Sarsen.<br />

Per circa quattrocento anni il santuario, così strutturato nella sua forma definitiva, fu<br />

con ogni probabilità uno dei fulcri religiosi della zona, per poi conoscere il definitivo<br />

abbandono a partire dal 1100 a.C., quando nella zona si affermò, stando ai ritrovamenti,<br />

una nuova cultura, chiamata <strong>di</strong> “Deverel-Rimbury”, il cui arrivo coincise con un<br />

grande cambiamento <strong>di</strong> costumi agricoli e religiosi: il tempo dei vecchi dei era giunto<br />

al termine, e così quello dei loro <strong>templi</strong>, che, come <strong>Stonehenge</strong>, furono abbandonati.<br />

Tuttavia il popolo delle Coppe fu importantissimo nella storia dell’Inghilterra <strong>preistoric</strong>a,<br />

come in<strong>di</strong>ca la grande abbondanza <strong>di</strong> monumenti megalitici a loro attribuibili,<br />

progetti architettonici chiaramente collettivi che testimoniano un or<strong>di</strong>ne sociale stabile<br />

e <strong>di</strong>ffuso, sostenuto da un evidente benessere economico e da una vastissima rete <strong>di</strong><br />

legami commerciali a largo raggio. Frutto <strong>di</strong> questa particolare realtà sociale ed<br />

economica risulta infatti essere anche l’altro gran<strong>di</strong>ssimo santuario <strong>preistoric</strong>o<br />

dell’Inghilterra del sud, il celeberrimo Cerchio <strong>di</strong> <strong>Avebury</strong>.<br />

Il villaggio <strong>di</strong> <strong>Avebury</strong> si trova in una piccola vallata del Wiltshire, circondato su tre<br />

lati dalle piccole colline <strong>di</strong> calcare gessoso caratteristiche della zona.<br />

La via principale, le case e i campi sono però interamente racchiusi da un argine e un<br />

fossato, circolari e concentrici, la cui circonferenza supera il chilometro e mezzo e al<br />

cui interno sorge uno dei più gran<strong>di</strong> <strong>templi</strong> megalitici <strong>di</strong> tutta Europa.<br />

La sua costruzione venne iniziata a partire dal 2500 a.C., con l’utilizzo, ancora una<br />

volta, <strong>di</strong> quella durissima arenaria locale<br />

<strong>Avebury</strong> come appare oggi<br />

<strong>Avebury</strong> as it appears today<br />

chiamata sarsen cui abbiamo già accennato<br />

a proposito <strong>di</strong> <strong>Stonehenge</strong>. Ancora oggi<br />

essa è visibile, in gran<strong>di</strong> blocchi, presso le<br />

cime delle colline circostanti.<br />

È evidente che allora, per motivi che non<br />

possiamo comprendere, enormi blocchi <strong>di</strong><br />

questa pietra dalla lavorazione assai <strong>di</strong>fficile<br />

vennero trasportati fino al fondovalle, dopo<br />

essere stati oggetto <strong>di</strong> una accurata selezione.<br />

La manodopera necessaria a questa<br />

operazione dovette essere assai numerosa,<br />

dal momento che per muovere anche una<br />

sola pietra servivano due gruppi <strong>di</strong> uomini,<br />

uno per trascinarla e uno per evitare che<br />

scivolasse troppo rapidamente giù dai pen<strong>di</strong>i.<br />

Una volta giunti a destinazione, i macigni<br />

vennero inseriti, grazie all’utilizzo <strong>di</strong><br />

corde e rulli, in apposite buche precedentemente<br />

scavate e poi stabilizzati grazie all’in-

heights near <strong>Avebury</strong>, about thirty-two kilometres away.<br />

This sandstone circle, with its regular curve and the perfection of its male-female joints<br />

linking the architraves and pillars in spite of the slope of the ground, does not cease to<br />

amaze modern observers and is a clear demonstration the incre<strong>di</strong>ble technical skills<br />

achieved by the Bronze Age peoples.<br />

Around 1550 BC the complex saw further changes, which in many ways are still a<br />

mystery. First of all a forest of wooden stakes, arranged in two concentric circles, was<br />

driven outside the Sarsen Circle. All that remains of these are the traces of very<br />

numerous stake-holes, called the Z and Y Circles by the archaeologists.<br />

In ad<strong>di</strong>tion the Blue Stones installed in the previous period were extracted from their<br />

seats and rearranged, in harmony with the stones used for the Sarsen circle, to form<br />

an oval within the Horseshoe. Shortly afterwards the arrangement of the Blue Stones<br />

was again mo<strong>di</strong>fied and the stones went to form two <strong>di</strong>stinct groupings, a small<br />

horseshoe within the larger, far more imposing horseshoe of trilithons and a new oval<br />

between the latter and the Sarsen Circle.<br />

For about four hundred years the temple, thus structured in its definitive form, was in<br />

all probability one of the religious fulcrums of the area, and was then definitively<br />

abandoned from 1100 BC onwards, when a new culture was established in the area,<br />

going by the remains, known as the “Deverel-Rimbury” culture, whose advent coincided<br />

with a great change in agricultural and religious customs: the age of the old gods<br />

had ended and so too had that of their<br />

<strong>temples</strong> which, like <strong>Stonehenge</strong>, were aban-<br />

La zona nord-ovest del Grande Circolo<br />

doned. However, the Bowl people were very<br />

important in the history of prehistoric England,<br />

as shown by the great abundance of megalithic<br />

monuments attributable to them, clearly<br />

collective architectural projects testifying to a<br />

stable, widespread social order, resting on<br />

evident economic prosperity and a very wide<br />

network of long-range commercial links.<br />

A fruit of this particular social and economic<br />

situation was also the other great prehistoric<br />

holy place of southern England, the famous<br />

<strong>Avebury</strong> Circle.<br />

<strong>The</strong> village of <strong>Avebury</strong> lies in a small valley in<br />

Wiltshire, surrounded on three sides by the<br />

low gypsum-chalk hills typical of the area.<br />

<strong>The</strong> main street, the houses and the fields<br />

<strong>The</strong> north-west area of the Major Circle<br />

are however entirely closed within a circular<br />

and concentric embankment and <strong>di</strong>tch, whose<br />

circumference exceeds one and a half kilometres and which contain one of the biggest<br />

megalithic <strong>temples</strong> in all Europe. Its construction began from 2500 BC, once again<br />

using the very hard local sandstone called sarsen which we have already mentioned in<br />

connection with <strong>Stonehenge</strong>. This can still be seen today in large blocks, near the tops<br />

of the surroun<strong>di</strong>ng hills. It is clear that then, for reasons which we cannot grasp, enormous<br />

blocks of this stone, which is quite <strong>di</strong>fficult to work, were brought down to the<br />

valley floor, after careful selection. <strong>The</strong> workforce required for this operation must have<br />

been quite numerous, as the moving of a single stone would have needed two groups<br />

of men, one to drag it and the other to prevent it from slipping down the slope too fast.<br />

Once they had reached their destination the huge stones were inserted into holes previously<br />

dug for the purpose and then stabilized by the insertion of smaller blocks as<br />

wedges. More than sixty stones of this kind were erected so as to form two circles of<br />

equal <strong>di</strong>ameter (just over a hundred metres) in the centre of the level area delimited by<br />

the embankment and <strong>di</strong>tch, while another hundred or so were arranged just inside<br />

from the <strong>di</strong>tch so as to form one gigantic ring. Thus, as early as 2400 BC, the site reached<br />

its definitive form: an enormous circular space, closed by a line of monoliths, a<br />

<strong>di</strong>tch and an embankment, from which four roads started out, crossing at right angles<br />

DIAMANTE Applicazioni & Tecnologia<br />

35

serzione <strong>di</strong> blocchi più piccoli come zeppe. Più <strong>di</strong> sessanta pietre <strong>di</strong> questo tipo<br />

vennero erette in modo da formare due cerchi <strong>di</strong> <strong>di</strong>ametro uguale (poco più <strong>di</strong> cento<br />

metri) al centro della spianata delimitata da argine e fossato, mentre un altro centinaio<br />

<strong>di</strong> esse venne <strong>di</strong>sposto appena all’interno del fossato in modo da formare un<br />

gigantesco anello. Così, già nel 2400 a.C. il santuario raggiunse la sua forma definitiva:<br />

un enorme spazio circolare, racchiuso da una fila <strong>di</strong> monoliti, un fossato e un terrapieno,<br />

da cui si <strong>di</strong>partivano quattro strade che si incrociavano perpen<strong>di</strong>colarmente e<br />

che si <strong>di</strong>rigevano verso le alture circostanti. L’unica <strong>di</strong> queste vie d’accesso che si sia<br />

conservata, anche se solo parzialmente, è la strada meri<strong>di</strong>onale, detta anche “<strong>di</strong> West<br />

Kennet”, la quale era contrassegnata da circa cento coppie <strong>di</strong> pietre <strong>di</strong>sposte lungo i<br />

suoi lati. Pur essendo <strong>di</strong> <strong>di</strong>mensioni assai variabili, esse sembrano essere state scelte<br />

secondo criteri particolari, ancorché incomprensibili. In vari punti della via vengono<br />

infatti a fronteggiarsi coppie <strong>di</strong> pietre dalla forma<br />

L’impressionante vista dell’argine e del fossato <strong>di</strong> <strong>Avebury</strong> particolare, come ad esempio una a forma <strong>di</strong><br />

pilastro e una a forma <strong>di</strong> losanga, interpretate<br />

perciò dagli stu<strong>di</strong>osi come espressioni <strong>di</strong> un culto<br />

della fecon<strong>di</strong>tà. È probabile che la stessa monumentalità<br />

fosse caratteristica anche delle altre<br />

tre Vie Processionali. All’interno del Grande<br />

Circolo vennero eretti, come si è già detto, due<br />

cerchi <strong>di</strong> pietre più piccoli, posti l’uno verso l’ingresso<br />

nord e uno verso quello sud.<br />

Del primo rimangono solo quattro delle ventisette<br />

pietre originarie, mentre decisamente più conservata<br />

appare la struttura al suo centro, chiamata<br />

la Grotta, costituita da tre file <strong>di</strong> pietre<br />

poste a ferro <strong>di</strong> cavallo.<br />

In origine doveva trattarsi <strong>di</strong> una nicchia rettangolare<br />

costruita a imitazione delle camere funerarie<br />

megalitiche, anche se, <strong>di</strong>versamente da<br />

quelle, non venne mai coperta da un tumulo <strong>di</strong><br />

terra. Perciò è probabile che questa struttura<br />

all’aperto servisse per alcuni rituali pubblici legati<br />

alla morte, a proposito dei quali però non è possibile<br />

<strong>di</strong>re altro. L’anello interno meri<strong>di</strong>onale<br />

venne invece costruito con una tale cura da formare<br />

un cerchio quasi perfetto, al cui centro si<br />

innalzava una grande pietra, alta oltre sei metri,<br />

chiamata l’Obelisco e infissa nel terreno in<br />

maniera tale da essere il fulcro <strong>di</strong> un’ulteriore<br />

struttura, dalla pianta a D, costituita da molte<br />

piccole pietre sarsen <strong>di</strong> forma irregolare.<br />

<strong>The</strong> impressive view of the embankment and <strong>di</strong>tch of <strong>Avebury</strong><br />

I due cerchi interni dovettero con ogni probabilità<br />

costituire due punti nodali separati per tutti i<br />

settecento anni in cui il santuario fu in uso.<br />

Contrariamente a <strong>Stonehenge</strong>, dove i rituali erano legati con ogni probabilità al moto<br />

del Sole e della Luna, ad <strong>Avebury</strong> emerge una religiosità collegata con tematiche<br />

totalmente <strong>di</strong>verse, quali la vita umana, la fertilità e la morte. Così sembrerebbero<br />

in<strong>di</strong>care le particolari forme <strong>di</strong> alcune pietre, <strong>di</strong> cui abbiamo già detto, nonché appunto<br />

il simbolismo connesso alle strutture poste al centro dei Circoli Minori.<br />

D’altra parte, la celebrazione dello scorrere della vita in tutte le sue forme, compresa<br />

la morte, doveva essere una parte molto importante del pensiero neolitico, stando<br />

anche alle raffigurazioni e alle incisioni rinvenute nelle tombe sotterranee del periodo.<br />

Sacralità della Vita e del Cosmo, volontà <strong>di</strong> comprendere i meccanismi dell’Esistenza e<br />

quin<strong>di</strong> rispetto per la Natura in ogni sua forma e attestazione furono dunque i motivi<br />

che spinsero gli abitatori <strong>di</strong> queste lande, e <strong>di</strong> tutta l’Europa megalitica, a compiere<br />

anche enormi sforzi per realizzare giganteschi santuari che ne accompagnassero e ne<br />

sancissero la progressiva conquista del territorio.<br />

Tra i molti monumenti dell’Inghilterra meri<strong>di</strong>onale, <strong>Stonehenge</strong> e <strong>Avebury</strong> sono<br />

giustamente glorificati non solo per la loro imponenza, ma anche perché rappresentano<br />

uno dei più gran<strong>di</strong> trionfi delle popolazioni <strong>preistoric</strong>he e, nella loro complessità,<br />

riassumono in sé tutti gli sforzi, le conoscenze, le speranze e anche le paure <strong>di</strong><br />

un’intera epoca ormai perduta.

Vista dall’entrata sud<br />

and hea<strong>di</strong>ng for the surroun<strong>di</strong>ng hills.<br />

<strong>The</strong> only one of these access roads that has been<br />

preserved, and this only partially, is the southern road, also<br />

called “West Kennet”, which was marked by about a hundred<br />

pairs of stones arranged along its sides.<br />

Although they are of quite a variable size, they seem to<br />

have been chosen accor<strong>di</strong>ng to particular criteria, which<br />

are however incomprehensible. At various points along the<br />

road there are pairs of stones of a particular shape facing<br />

each other, such as one in a pillar shape and the other a<br />

lozenge, thus interpreted by scholars as expressions of a<br />

fertility cult. <strong>The</strong> same monumental nature is also likely to<br />

have characterised the other three Processional Roads.<br />

Within the Major Circle, as has already been said, two<br />

circles of smaller stones were erected, one near the north<br />

entrance and the other near the south entrance.<br />

Of the first there remain only four of the original twentyseven<br />

stones, while the structure at its centre is decidedly better preserved, known as<br />

the Cave and made up of three rows of stones in a horseshoe arrangement.<br />

It must originally have been a rectangular niche built in imitation of the megalithic funeral<br />

chambers, although, unlike these, it was never covered by an earth mound.<br />

This open-air structure is thus likely to have been used for some public rituals linked to<br />

death, about which it is not however possible to say more.<br />

<strong>The</strong> inner southern ring on the other hand was built with such care that it formed an<br />

almost perfect circle, with a great stone over six metres high rising in the centre,<br />

known as the Obelisk and fixed in the ground so as to be the fulcrum of a further<br />

structure, with a D plan, made up of small, irregular-shaped sarsen stones.<br />

<strong>The</strong> two inner circles must in all probability have formed two separated nodal points<br />

throughout the seven hundred years in which the site was in use.<br />

Unlike <strong>Stonehenge</strong>, where the rituals were very likely related to the movement of the<br />

Sun and the Moon, at <strong>Avebury</strong> there emerges a religiousness<br />

linked to completely <strong>di</strong>fferent themes, such as human<br />

life, fertility and death. This would seem to be in<strong>di</strong>cated by<br />

the particular shapes of some stones, which we have<br />

already mentioned, as well as the symbolism connected<br />

with the structures at the centre of the Minor Circles.<br />

On the other hand, the celebration of the passing of life in<br />

all its forms, inclu<strong>di</strong>ng death, must have been an important<br />

part of Neolithic thought, going by the portrayals and<br />

carvings found in the underground tombs of the period.<br />

Sacredness of Life and the Cosmos, the desire to understand<br />

the mechanisms of<br />

existence and therefore respect for Nature in all its forms<br />

and attestations were therefore the motives that drove the<br />

inhabitants of these plains, and of all megalithic Europe, to<br />

make enormous efforts to build gigantic holy places which<br />

accompanied and sanctioned the gradual conquest of the<br />

territory.<br />

Of the many monuments of southern England, <strong>Stonehenge</strong><br />

and <strong>Avebury</strong> are rightly celebrated not only for their imposing<br />

nature but also because they represent one of the<br />

great triumphs of the prehistoric peoples and, in their<br />

complexity, sum up all the efforts, knowledge, hopes and<br />

also fears of an entire epoch, now lost.<br />

View from the south entrance<br />

Ricostruzione dei culti <strong>di</strong> <strong>Avebury</strong><br />

Reconstruction of the cults of <strong>Avebury</strong><br />

DIAMANTE Applicazioni & Tecnologia<br />

37

![Kirchner-Munch-Turner-klimt-Fussli - art]è school](https://img.yumpu.com/41667417/1/184x260/kirchner-munch-turner-klimt-fussli-arta-school.jpg?quality=85)

![LA SCUOLA DI BARBIZON Corot, Monet, Sisley e ... - art]è school](https://img.yumpu.com/41547843/1/184x260/la-scuola-di-barbizon-corot-monet-sisley-e-arta-school.jpg?quality=85)