an emblematic figure an emblematic figure - Venice Magazine

an emblematic figure an emblematic figure - Venice Magazine

an emblematic figure an emblematic figure - Venice Magazine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

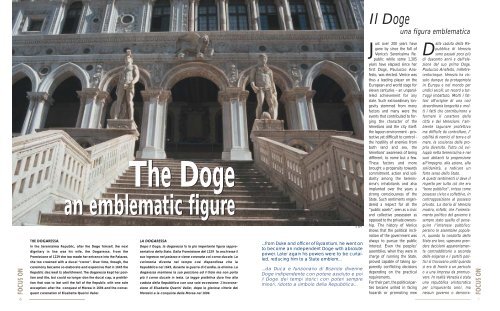

Il Dogeuna figura <strong>emblematic</strong>aFOCUS ON6The Doge<strong>an</strong> <strong>emblematic</strong> <strong>figure</strong>THE DOGARESSALA DOGARESSAIn the Serenissima Republic, after the Doge himself, the next Dopo il Doge, la dogaressa fu la più import<strong>an</strong>te figura rappresentativadello Stato. Dalla Promissione del 1229 fa <strong>an</strong>ch'essa ildignitary in line was his wife, the Dogaressa. From thePromissione of 1229 she too made her entr<strong>an</strong>ce into the Palazzo, suo ingresso nel palazzo e viene coronata col corno ducale. Lashe too crowned with a ducal “corno”. Over time, though, the cerimonia diventa nel tempo così dispendiosa che laceremony became so elaborate <strong>an</strong>d expensive that in 1645 the Repubblica nel 1645, dur<strong>an</strong>te la guerra di C<strong>an</strong>dia, la elimina. LaRepublic decreed its abolishment. The dogaressa kept her position<strong>an</strong>d title, but could no longer don the ducal cap, a prohibi-più il corno ducale in testa. La legge proibitiva dura fino alladogaressa m<strong>an</strong>tiene la sua posizione ed il titolo ma non portation that was to last until the fall of the Republic with one sole caduta della Repubblica con una sola eccezione: 1'incoronazionedi Elisabetta Querini Valier, dopo le gloriose vittorie delexception: after the conquest of Morea in 1694 <strong>an</strong>d the consequentcoronation of Elisabetta Querini Valier.Morosini e la conquista della Morea nel 1694.© APT...from Duke <strong>an</strong>d officer of Byz<strong>an</strong>tium, he went onto become <strong>an</strong> independent Doge with absolutepower. Later again his powers were to be curtailed,reducing him to a State emblem......da Duca e funzionario di Bis<strong>an</strong>zio divenneDoge indipendente con potere assoluto e poiil Doge dei tempi storici con poteri sempreminori, ridotto a simbolo della Repubblica...Just over 200 years havegone by since the fall of<strong>Venice</strong>’s Serenissima Republic while some 1,305years have elapsed since herfirst Doge, Pauluccio Anafesto,was elected. <strong>Venice</strong> wasthus a leading player on theEurope<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d world stage foreleven centuries – <strong>an</strong> unparalleledachievement for <strong>an</strong>ystate. Such extraordinary longevitystemmed from m<strong>an</strong>yfactors <strong>an</strong>d m<strong>an</strong>y were theevents that contributed to forgingthe character of theVeneti<strong>an</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d the city itself:the lagoon environment - protectiveyet difficult to control -the hostility of enemies fromboth l<strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong>d sea, theVeneti<strong>an</strong>s’ awareness of beingdifferent, to name but a few.These factors <strong>an</strong>d morebrought a propensity towardscommitment, action <strong>an</strong>d solidarityamong the Serenissima'sinhabit<strong>an</strong>ts <strong>an</strong>d alsoimpl<strong>an</strong>ted over the years astrong consciousness of theState. Such sentiments engendereda respect for all the“public assets”, seen as a civic<strong>an</strong>d collective possession asopposed to the private ownership.The history of <strong>Venice</strong>shows that the political inclinationof the government wasalways to pursue the publicinterest. Even the peoples'assemblies, when they were incharge of running the State,proved capable of taking apparentlyconflicting decisionsdepending on the practicalrequirements.For their part, the political partiesbecame united in facinghazards or promoting newDalla caduta della Repubblicadi Veneziasono passati poco piùdi duecento <strong>an</strong>ni e dall'elezionedel suo primo Doge,Pauluccio Anafesto, milletrecentocinque.Venezia ha vissutodunque da protagonistain Europa e nel mondo perundici secoli: un record a tutt'oggiimbattuto. Molti i fattoriall'origine di una cosìstraordinaria longevità e moltii fatti che contribuirono aformare il carattere dellacittà e dei Venezi<strong>an</strong>i: l'ambientelagunare protettivoma difficile da controllare, l'ostilità di nemici di terra e dimare, la coscienza della propriadiversità. Tutto ciò sviluppònella Serenissima e neisuoi abit<strong>an</strong>ti la propensioneall'impegno, alla azione, allasolidarietà, a radicare unforte senso dello Stato.A questi sentimenti si deve ilrispetto per tutto ciò che era"bene pubblico", inteso comepossesso civico e collettivo, incontrapposizione al possessoprivato. La storia di Veneziamostra, infatti, che l'orientamentopolitico del governo èsempre stato quello di perseguirel'interesse pubblico;persino le assemblee popolari,qu<strong>an</strong>do la condotta delloStato era loro, sapev<strong>an</strong>o prenderedecisioni apparentementecontraddittorie a secondadelle esigenze e i partiti politicisi trovav<strong>an</strong>o uniti qu<strong>an</strong>dosi era di fronte a un pericoloo a una impresa da promuovere.In realtà Venezia è statauna repubblica aristocraticaper cinquecento <strong>an</strong>ni, m<strong>an</strong>essun governo o democra-FOCUS ON7

FOCUS ON8ventures. <strong>Venice</strong> was <strong>an</strong> aristocraticrepublic for 500 years,but no government or democracyhas ever succeeded inexerting the power the Serenissimawielded with suchdexterity: the control of power,its limiting <strong>an</strong>d ch<strong>an</strong>nellingtowards what was consideredto be the best for “the commongood”.The <strong>figure</strong> of the Doge is<strong>emblematic</strong> in this scenario.A <strong>figure</strong> evolving over the centuries,he resided first on thecoast, at Eraclea, then Malamocco,<strong>an</strong>d lastly on <strong>Venice</strong>'smain isl<strong>an</strong>d, at Rialto, fromDuke <strong>an</strong>d officer of Byz<strong>an</strong>tium,he went on to become<strong>an</strong> independent Doge withabsolute power. Later againhis powers were to be curtailed,reducing him to a Stateemblem, still aloof but a meresymbol of the Gr<strong>an</strong>d Republic.In solemnitatibus imperator,in curia senator,in urbe captivus, ex urbe reus.Electoral law ch<strong>an</strong>ged overthe centuries. The one of 1268- which aimed above all at preventingballot rigging - lasted,with a few variations, until thefall of the Republic. Uponappointment, the Doge wascalled to swear his “Promissioneducale”, the oath regulatinghis powers. Since the 13thcentury, responsibility forch<strong>an</strong>ging it according to theneeds was in the h<strong>an</strong>ds theCorrettori della Promissione;in 1501, these <strong>figure</strong>s wereadded to by the Inquisitors,who, after the death of theDoge, checked that he hadkept faith to his oath. Thepolitical scope of the Doge’sactivity was extremely limited.Without permission, he couldnot renounce his appointmentbut could be forced out ofoffice; he could not increasehis powers, nor own assetsTHE DOGES' CLOTHESThe best-known feature of the Doges' attire is the traditional small hat,which was called the "corno” (horn) for its characteristic pointed shape.It was soft in the first years - somewhat reminiscent the berets of theOrient (the Doges' robes were inspired by Byz<strong>an</strong>tine tastes) - while inaround 1200 it became stiffer <strong>an</strong>d conical, as one of the symbols of thecoronation. The Doge would wear a cap of gold or silver cloth, scarletfabric, damask, <strong>an</strong>d crimson velvet. At his coronation, he was crownedwith the “zoia”, a "corna" encrusted with precious gems that belonged tothe State <strong>an</strong>d kept by the Procuratori of St. Mark. To have <strong>an</strong> inkling of itsvalue, the zoia renewed in 1555 was estimated at 194,092 ducats. Underthe peak, the Doge would wear a smaller cap of fine cloth, called“rensa”, which was worn even during the elevation ceremony in church.The ceremonial garb was made up of the dogalina, a sort of cassock, themajestic ducal m<strong>an</strong>tle, <strong>an</strong>d the collar. The dogalina <strong>an</strong>d the m<strong>an</strong>tle weremade of fabric while the collar, fastened with a gold clasp or bejewelled,was in fur. The stockings <strong>an</strong>d shoes, which were leather or fabricboots, were red. When not seen in public, the doge wore the Rom<strong>an</strong>a, ashaved crimson gown while, to attend the Councils, he put on a similarone called collegiale. The Doges' costume did not undergo <strong>an</strong>y greatch<strong>an</strong>ges over the centuries.Two curious things are worth noting about the doges' appear<strong>an</strong>ce: first,their hair, which was at first worn long, then short <strong>an</strong>d then long againuntil, in the 18th century, it was ‘replaced’ by powdered wigs; the other isthat they could never wear <strong>an</strong>ything which was black.I VESTITI DEI DOGIIl particolare più noto dell’abbigliamento dei Dogi è il tradizionale berrettoche si chiamava “corno” per la sua caratteristica forma a punta.All’inizio era morbido e ricordava i berretti del vicino Oriente (gli abiti deiDogi er<strong>an</strong>o del resto ispirati al gusto biz<strong>an</strong>tino) mentre attorno al 1200diventò più rigido, di forma conica, uno dei simboli dell’incoronazione.Il Doge infatti usualmente portava un corno di tessuto d'oro o d'argento,di p<strong>an</strong>no scarlatto, di damasco, di velluto cremisi, mentre venivaincoronato con la “zoia”, un corno ricoperto di pietre preziose cheapparteneva allo Stato e veniva custodito dai procuratori di S. Marco.Per dare una idea del suo valore basti dire che quello rinnovato nel 1555fu stimato la somma di 194.092 ducati.Sotto il corno indossava una cuffietta di tela finissima di nome “rensa”che neppure dur<strong>an</strong>te l'elevazione in chiesa veniva tolta. Il vestito di cerimoniasi componeva della dogalina, specie di veste talare, del maestosom<strong>an</strong>to ducale e del bavero.La dogalina ed il m<strong>an</strong>to er<strong>an</strong>o di stoffa, mentre il collare fermato conborchia d'oro o gemmata era di pelliccia. Le calze e le scarpe, stivalettidi pelle o di stoffa, er<strong>an</strong>o di colore rosso. Privatamente il doge indossavala rom<strong>an</strong>a, veste di raso cremisi, e per assistere ai Consigli una similedetta collegiale. Il costume del Doge sost<strong>an</strong>zialmente non cambiò nelcorso dei secoli. Due sono le curiosità, una riguarda i capelli che furonoprima lunghi, poi corti ed <strong>an</strong>cora lunghi fino ad essere sostituiti nel XVIIIsecolo da parrucche incipriate e l’altra il fatto che il Doge non potevamai portare il colore nero.Leonardo Lored<strong>an</strong> Doge (1501 - 1521)Giov<strong>an</strong>ni Bellini - London, National Gallery.zia, seppur retto da un<strong>an</strong>omenclatura di elite, ha maisaputo esercitare così bene ilpotere acquisito, cioè controllarloe limitarlo, indirizz<strong>an</strong>doloverso ciò che era ritenutoessere il meglio, per il cosidettobene "nostro".La figura del Doge è <strong>emblematic</strong>ain questo scenario.La sua fisionomia non è statasempre la stessa. Residenteprima ad Eraclea, poi aMalamocco ed infine a Rialto,da Duca e funzionario diBis<strong>an</strong>zio divenne Doge indipendentecon potere assolutoe poi il Doge dei tempi storicicon poteri sempre minori,ridotto a simbolo della gr<strong>an</strong>deRepubblica ed insegnadello Stato.In solemnitatibus imperator,in curia senator,in urbe captivus, ex urbe reus.La legge elettorale mutò nelcorso dei secoli, quella del1268 durò con poche vari<strong>an</strong>ti,volte sopratutto ad evitarebrogli, fino alla caduta dellaRepubblica.Il Doge, al momento dell<strong>an</strong>omina, doveva giurare la"Promissione ducale" cheregolava i suoi poteri.A modificarla secondo lenecessità si occuparono, finodal secolo XIII, i Correttoridella Promissione; ad essivennero, nel 1501, aggiuntigli Inquisitori che verificav<strong>an</strong>oche il Doge defunto laavesse osservata. L'attivitàpolitica del Doge era limitatissima.Non poteva rinunciaresenza permesso al dogado,ma poteva essere costrettoa farlo, aumentare i suoipoteri e possedere beni fuoridello Stato. Non poteva,senza l'assistenza e il permessodei suoi consiglieri, riceverepersonaggi in veste ufficiale,dare risposte agli ambasciatori,spedire o aprire letoutsidethe State; he could notreceive persons in his officialcapacity, give official <strong>an</strong>swersto ambassadors, send or openletters of State, or receive gifts.He also had to pay taxes.He could not leave <strong>Venice</strong>without permission from theGr<strong>an</strong>d Council. He was notallowed to flaunt his presencein the cafés or theatres, couldonly go out when dressed likethe other patrici<strong>an</strong>s, not enjoyingspecial honours. Despiteall these restrictions, the Dogewas free to preside over all theState’s meetings, at which hecould both make proposals<strong>an</strong>d take part in the voting.Public deeds had to bear thedoge’s signature <strong>an</strong>d he hadthe responsibility of supervisingover the good working ofthe magistracies <strong>an</strong>d justicesystems. He had to belong to afamily of the Gr<strong>an</strong>d Council<strong>an</strong>d, at least according to therules, he had to be youngerth<strong>an</strong> forty. In practice, though,doges were chosen from oldercitizens for their experience<strong>an</strong>d so that they would notremain in office for too long.As to their personal capacities,they were not required to haveexceptionally-gifted intellects,it being enough that they werenot completely inept, that theywere healthy <strong>an</strong>d showed acertain degree of ability in theart of negotiation. After hisdeath, a portrait was paintedof him at the Republic'sexpense <strong>an</strong>d put up in theDoges’ Palace. On 4 June1797, with the fall of theRepublic, in the midst of theMunicipalists’ jubilation, theducal insignias were burnt ona bonfire, together with thegolden book, <strong>an</strong>d the ashesthrown to the wind. Howquickly the fame of the worldpasses: sic tr<strong>an</strong>seat gloriamundi.tere di Stato, ricevere doni.Doveva pagare le imposte,pur con qualche agevolazione.Non poteva lasciare Veneziasenza il permesso del MaggiorConsiglio. Non gli erapermesso di <strong>an</strong>dare ai caffè enei teatri o mettersi in vista:qu<strong>an</strong>do usciva vestiva comegli altri patrizi e non avevaonori speciali. Pur con questilimiti ad un Doge rim<strong>an</strong>evaun buon campo d’azione: presiedeva,però, tutti i consessidello Stato e poteva proporree votare. Gli atti pubblicidovev<strong>an</strong>o portare la suafirma, doveva vigilare sulbuon <strong>an</strong>damento delle magistraturee sulla amministrazionedella giustizia.Doveva appartenere ad unafamiglia iscritta nel MaggiorConsiglio ed avere un'etàinferiore ai quar<strong>an</strong>ta <strong>an</strong>ni.In realtà si scegliev<strong>an</strong>o piùvecchi per esperienza e perchénon rim<strong>an</strong>essero molto alungo sul trono.Non doveva possedere gr<strong>an</strong>die straordinarie doti intellettuali,bastava che non fosseun'assoluta nullità e cheavesse prest<strong>an</strong>za fisica e capacitànel trattare.La lista civile fu sempre esiguae perciò doveva esserericco per poter sostenere lacarica. Nelle gr<strong>an</strong>di cerimoniee nelle processioni seguiv<strong>an</strong>oil Doge le insegne ed idistintivi particolari della suaalta dignità. Dopo la morteun suo ritratto veniva dipinto,a spese della Repubblica,e collocato in Palazzo Ducale.Il 4 giugno 1797, caduta laRepubblica, in mezzo al pazzescotripudio dei Municipalisti,le insegne dogalivennero arse sopra un rogoinsieme al libro d'oro e le cenerisparse al vento.Ma sono cose che accadono:sic tr<strong>an</strong>seat gloria mundi.FOCUS ON9