Java.July.2016

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

ARTS<br />

THE NEW ANIMIST<br />

By Amy L. Young<br />

Animism is the age-old belief that non-human<br />

entities, like animals, plants and rivers, can have<br />

a soul or spiritual essence. For those who hold<br />

this belief, it affects how they perceive and treat<br />

elements of the natural environment. Though the<br />

unfortunate continued disregard and decimation of<br />

elements from our natural world is part of daily life,<br />

awareness continues to grow, with a growing list of<br />

advocates to foster change.<br />

The New Animist, an exhibition at ASU Art Museum<br />

created by Kev Nemelka, presents pieces from the<br />

museum’s permanent collection that highlight an<br />

elevated level of eco-awareness while also outlining<br />

how animist beliefs parallel the collective concern<br />

for our present-day environment. In keeping with<br />

today’s meta-oriented culture, the show itself serves<br />

to promote a strengthened relationship with nature<br />

that occurs from the use of many non-natural means<br />

to facilitate knowledge, and thereby action.<br />

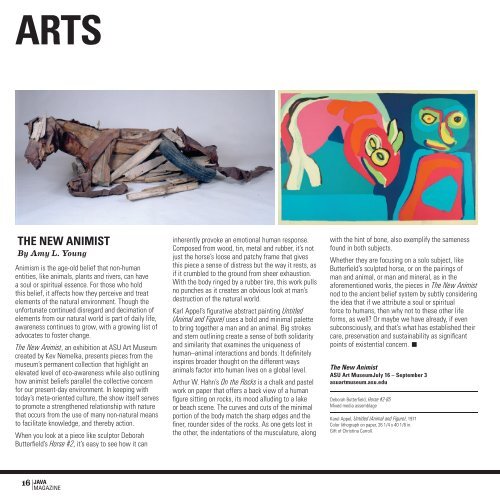

When you look at a piece like sculptor Deborah<br />

Butterfi eld’s Horse #2, it’s easy to see how it can<br />

inherently provoke an emotional human response.<br />

Composed from wood, tin, metal and rubber, it’s not<br />

just the horse’s loose and patchy frame that gives<br />

this piece a sense of distress but the way it rests, as<br />

if it crumbled to the ground from sheer exhaustion.<br />

With the body ringed by a rubber tire, this work pulls<br />

no punches as it creates an obvious look at man’s<br />

destruction of the natural world.<br />

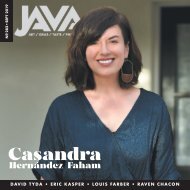

Karl Appel’s figurative abstract painting Untitled<br />

(Animal and Figure) uses a bold and minimal palette<br />

to bring together a man and an animal. Big strokes<br />

and stern outlining create a sense of both solidarity<br />

and similarity that examines the uniqueness of<br />

human–animal interactions and bonds. It definitely<br />

inspires broader thought on the different ways<br />

animals factor into human lives on a global level.<br />

Arthur W. Hahn’s On the Rocks is a chalk and pastel<br />

work on paper that offers a back view of a human<br />

fi gure sitting on rocks, its mood alluding to a lake<br />

or beach scene. The curves and cuts of the minimal<br />

portion of the body match the sharp edges and the<br />

fi ner, rounder sides of the rocks. As one gets lost in<br />

the other, the indentations of the musculature, along<br />

with the hint of bone, also exemplify the sameness<br />

found in both subjects.<br />

Whether they are focusing on a solo subject, like<br />

Butterfi eld’s sculpted horse, or on the pairings of<br />

man and animal, or man and mineral, as in the<br />

aforementioned works, the pieces in The New Animist<br />

nod to the ancient belief system by subtly considering<br />

the idea that if we attribute a soul or spiritual<br />

force to humans, then why not to these other life<br />

forms, as well? Or maybe we have already, if even<br />

subconsciously, and that’s what has established their<br />

care, preservation and sustainability as significant<br />

points of existential concern.<br />

The New Animist<br />

ASU Art MuseumJuly 16 – September 3<br />

asuartmuseum.asu.edu<br />

Deborah Butterfield, Horse #2-85<br />

Mixed media assemblage<br />

Karel Appel, Untitled (Animal and Figure), 1971<br />

Color lithograph on paper, 26 1/4 x 40 1/8 in.<br />

Gift of Christina Carroll.<br />

16 JAVA<br />

MAGAZINE