Colloid cyst Spetzler vs endoscope

Colloid cyst Spetzler vs endoscope

Colloid cyst Spetzler vs endoscope

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Eric M. Horn, M.D., Ph.D.<br />

Division of Neurological Surgery,<br />

Barrow Neurological Institute,<br />

St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center,<br />

Phoenix, Arizona<br />

Iman Feiz-Erfan, M.D.<br />

Division of Neurological Surgery,<br />

Barrow Neurological Institute,<br />

St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center,<br />

Phoenix, Arizona<br />

Ruth E. Bristol, M.D.<br />

Division of Neurological Surgery,<br />

Barrow Neurological Institute,<br />

St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center,<br />

Phoenix, Arizona<br />

Gregory P. Lekovic, M.D.,<br />

Ph.D., J.D.<br />

Division of Neurological Surgery,<br />

Barrow Neurological Institute,<br />

St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center,<br />

Phoenix, Arizona<br />

Pamela W. Goslar, Ph.D.<br />

Division of Trauma,<br />

St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center,<br />

Phoenix, Arizona<br />

Kris A. Smith, M.D.<br />

Division of Neurological Surgery,<br />

Barrow Neurological Institute,<br />

St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center,<br />

Phoenix, Arizona<br />

Peter Nakaji, M.D.<br />

Division of Neurological Surgery,<br />

Barrow Neurological Institute,<br />

St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center,<br />

Phoenix, Arizona<br />

Robert F. <strong>Spetzler</strong>, M.D.<br />

Division of Neurological Surgery,<br />

Barrow Neurological Institute,<br />

St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center,<br />

Phoenix, Arizona<br />

Reprint requests:<br />

Robert F. <strong>Spetzler</strong>, M.D.,<br />

c/o Neuroscience Publications,<br />

Barrow Neurological Institute,<br />

350 West Thomas Road,<br />

Phoenix, AZ 85013.<br />

Email: neuropub@chw.edu<br />

Received, June 1, 2006.<br />

Accepted, December 5, 2006.<br />

TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR THIRD VENTRICULAR<br />

COLLOID CYSTS: COMPARISON OF OPEN<br />

MICROSURGICAL VERSUS ENDOSCOPIC RESECTION<br />

OBJECTIVE: We retrospectively reviewed our experience treating third ventricular colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s to compare the efficacy of endoscopic and transcallosal approaches.<br />

METHODS: Between September 1994 and March 2004, 55 patients underwent third ventricular<br />

colloid <strong>cyst</strong> resection. The transcallosal approach was used in 27 patients; the<br />

endoscopic approach was used in 28 patients. Age, sex, <strong>cyst</strong> diameter, and presence of<br />

hydrocephalus were similar between the two groups.<br />

RESULTS: The operating time and hospital stay were significantly longer in the transcallosal<br />

craniotomy group compared with the endoscopic group. Both approaches<br />

led to reoperations in three patients. The endoscopic group had two subsequent craniotomies<br />

for residual <strong>cyst</strong>s and one repeat endoscopic procedure because of equipment<br />

malfunction. The transcallosal craniotomy group had two reoperations for fractured<br />

drainage catheters and one operation for epidural hematoma evacuation. The transcallosal<br />

craniotomy group had a higher rate of patients requiring a ventriculoperitoneal<br />

shunt (five versus two) and a higher infection rate (five versus none). Intermediate follow-up<br />

demonstrated more small residual <strong>cyst</strong>s in the endoscopic group than in the<br />

transcallosal craniotomy group (seven versus one). Overall neurological outcomes,<br />

however, were similar in the two groups.<br />

CONCLUSION: Compared with transcallosal craniotomy, neuroendoscopy is a safe<br />

and effective approach for removal of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s in the third ventricle. The <strong>endoscope</strong><br />

can be considered a first-line treatment for these lesions, with the understanding<br />

that a small number of these patients may need an open craniotomy to remove residual<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s.<br />

KEY WORDS: Hydrocephalus, Intracranial tumor, Intraventricular<br />

CLINICAL STUDIES<br />

Neurosurgery 60:613–620, 2007 DOI: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000255409.61398.EA www.neurosurgery-online.com<br />

<strong>Colloid</strong> <strong>cyst</strong>s are benign intracranial<br />

lesions that account for 0.5 to 1.0% of<br />

brain tumors. They are almost always<br />

located in the third ventricle (6, 35). They typically<br />

present with progressive headaches<br />

caused by obstructive hydrocephalus (16, 43).<br />

A few patients, however, have signs of severe<br />

obstructive hydrocephalus and present with<br />

sudden death (17). Consequently, early detection<br />

and treatment are recommended.<br />

The traditional treatment for these <strong>cyst</strong>s has<br />

been a transcallosal or transcortical craniotomy<br />

and resection. Increasingly, however, the <strong>endoscope</strong><br />

is being used for resection. Therefore,<br />

we retrospectively reviewed our experience<br />

treating third ventricular colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s to com-<br />

pare the efficacy of the endoscopic and transcallosal<br />

approaches.<br />

PATIENTS AND METHODS<br />

The surgical database at the Barrow Neurological<br />

Institute was retrospectively reviewed<br />

for all patients undergoing operation for colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s. The endoscopic approach for treating<br />

colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle was initiated<br />

at our institution during the early 1990s,<br />

and this review spans from September 1994 to<br />

March 2004. During this time, 55 consecutive<br />

patients were treated for third ventricular colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s; 27 patients underwent a transcallosal<br />

approach and 28 underwent an endo-<br />

NEUROSURGERY VOLUME 60 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2007 | 613

HORN ET AL.<br />

scopic approach. The proportions of approaches were similar<br />

throughout the study period (seven endoscopic and four transcallosal<br />

approaches between 1994 and 1996; 13 endoscopic<br />

and nine transcallosal approaches between 1997 and 2000; eight<br />

endoscopic and 14 transcallosal approaches between 2001 and<br />

2004). The most common presenting symptom in both groups<br />

was headache (Table 1). At presentation, there were no differences<br />

in age, sex, <strong>cyst</strong> diameter, or presence of hydrocephalus<br />

between the two groups (Table 1). The rationale for resection<br />

was based on presenting symptoms. If the patient had a severe<br />

headache from hydrocephalus or neurological symptoms, surgery<br />

was offered. If the patient was asymptomatic or had mild<br />

symptoms, then surgery or observation was offered. Only<br />

patients who underwent surgery were included in the study.<br />

The decision to use either approach was based on the preference<br />

of the eight treating surgeons. Four surgeons used the<br />

transcallosal approach exclusively, and three surgeons used the<br />

endoscopic approach exclusively. One surgeon used the endoscopic<br />

approach in all but one case in which the transcallosal<br />

approach was used because two endoscopic attempts at an outside<br />

facility had failed. Thus, the groups were well matched in<br />

terms of presentation. The choice of approach was based solely<br />

on the patient’s treating physician.<br />

Standard microsurgical techniques were used in patients<br />

undergoing the transcallosal approach. A rigid <strong>endoscope</strong> was<br />

manipulated freehand in all patients undergoing the endoscopic<br />

approach (Fig. 1). All <strong>endoscope</strong>s used had either a 0- or<br />

30-degree viewing angle with one channel for insertion of<br />

microinstruments. Because its use became routine for all cranial<br />

operations at our institution before the study period, image<br />

guidance was used equally with the two approaches.<br />

The primary outcomes compared between the two<br />

approaches were operative time, complications, length of hospitalization,<br />

and residual or recurrence of <strong>cyst</strong>. Each patient’s<br />

last follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed<br />

tomographic scan was used to evaluate the presence of residual<br />

or recurrent <strong>cyst</strong>s (range, 1–54 mo). Intermediate neurological<br />

outcomes were also compared, with special attention to memory,<br />

motor, and cognitive deficits, as measured by standard<br />

TABLE 1. Demographic information for patients undergoing<br />

endoscopic or transcallosal approaches for removal of third ventricular<br />

colloid <strong>cyst</strong>sa Endoscopic Transcallosal<br />

(n � 28) (n � 27)<br />

Age (mean � SD) 49 � 14 yr 45 � 15 yr<br />

Men (no. men/total patients)<br />

Presentation<br />

50% (14/28) 48% (13/27)<br />

Headache (no./total) 75% (21/28) 56% (15/27)<br />

Neurological sign (no./total) 21% (6/28) 26% (7/27)<br />

Incidental (no./total) 4% (1/28) 19% (5/27)<br />

Cyst diameter (mean � SD) 1.3 � 0.5 cm 1.3 � 0.5 cm<br />

Hydrocephalus (no./total) 61% (17/28) 63% (17/27)<br />

a SD, standard deviation.<br />

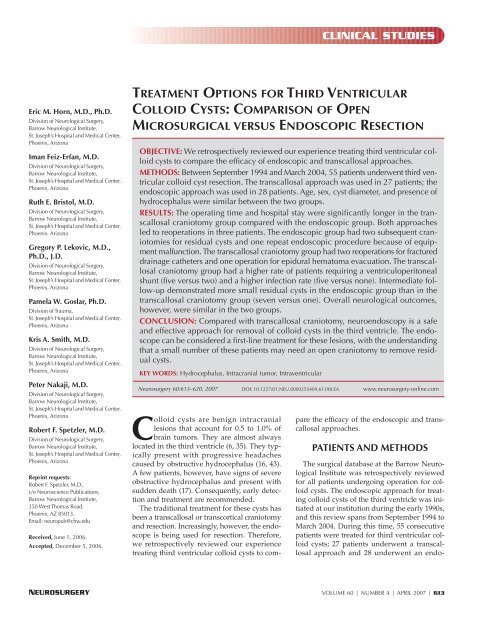

A B<br />

FIGURE 1. A, immediate preoperative axial T1-weighted MRI scan with<br />

contrast shows a colloid <strong>cyst</strong> in the foramen of Monro. B, axial T1-weighted<br />

MRI scan without contrast 2 weeks after endoscopic resection.<br />

neuropsychological tests. These variables were analyzed using<br />

Fisher’s exact test, Student’s t test, or Mann-Whitney rank sum<br />

test, with P values less than 0.05 deemed significant.<br />

RESULTS<br />

The operating time was significantly longer in the transcallosal<br />

craniotomy group than in the endoscopic group (Table 2).<br />

The length of stay in the intensive care unit was similar in the<br />

two groups but the overall length of hospitalization was<br />

TABLE 2. Procedural and postoperative hospital stay comparisons<br />

between patients treated via an endoscopic or transcallosal<br />

craniotomy resection of third ventricular colloid <strong>cyst</strong>sa Endoscopic Transcallosal<br />

(n � 28) (n � 27)<br />

Operative time (mean � SEM) 173.9 � 6.3 266.8 � 8.4<br />

min minb Complications<br />

None (no./total) 75% (21/28) 56% (15/27)<br />

Reoperation (no./total) 11% (3/28) 11% (3/27)<br />

VPS (no./total) 7% (2/28) 19% (5/27)<br />

Infection (no./total) 0% (0/28) 19% (5/27)<br />

Neurological (no./total) 11% (3/28) 11% (3/27)<br />

Other (no./total) 0% (0/28) 4% (1/27)<br />

ICU stay (mean � SEM) 2.3 � 0.4 d 3.3 � 0.6 d<br />

Hospital stay (mean � SEM) 5.4 � 1.3 d 6.3 � 0.8 db Discharge destination<br />

Home (no./total) 89% (25/28) 93% (25/27)<br />

Rehabilitation (no./total) 7% (2/28) 4% (1/27)<br />

ECF (no./total) 4% (1/28) 4% (1/27)<br />

a SEM, standard error of the means; VPS, ventriculoperitoneal shunt; ICU, intensive<br />

care unit; ECF, extended care facility.<br />

b P �0.05.<br />

614 | VOLUME 60 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2007 www.neurosurgery-online.com

slightly longer in the transcallosal craniotomy group (Table 2).<br />

The overall complication rate was slightly higher in the transcallosal<br />

group than in the craniotomy group but this finding<br />

was nonsignificant (Table 2). Except for the presence of hydrocephalus,<br />

there were no differences in the complication rates<br />

across any of the categories of presentation. Patients who presented<br />

with hydrocephalus had a higher complication rate<br />

(47%) than those without hydrocephalus (19%).<br />

In each approach, three patients underwent reoperation<br />

(Table 2). In the endoscopic group, two patients underwent a<br />

subsequent craniotomy for residual <strong>cyst</strong>s. One patient underwent<br />

another endoscopic procedure because equipment malfunctioned<br />

during the original approach. In the transcallosal<br />

craniotomy group, two patients required a reoperation for<br />

fractured drainage catheters, and an epidural hematoma was<br />

evacuated in one patient. Five patients in the transcallosal craniotomy<br />

group required a ventriculoperitoneal shunt compared<br />

with two patients in the endoscopic group. A significant<br />

residual was not found in any of the patients who subsequently<br />

required shunting. One potential reason for persistent hydrocephalus<br />

in these patients was the presence of blood products<br />

in the cerebrospinal fluid from the surgical procedure. The<br />

infection rate was also higher in the transcallosal craniotomy<br />

group than in the endoscopic group (five versus none). Postoperatively,<br />

all patients had an external drain in place while in<br />

the intensive care unit. Therefore, this difference in infection<br />

rate may reflect the longer (but nonsignificant) intensive care<br />

unit stay of 1 day in the transcallosal group.<br />

The number of neurological complications in the two groups<br />

was similar. In the transcallosal craniotomy group, two patients<br />

developed new-onset seizures and one patient experienced a<br />

venous infarct. In the endoscopic group, two patients had significant<br />

memory impairment and one patient had hemiparesis<br />

from an internal capsule injury. In both groups, a similar number<br />

of patients were discharged to home, a rehabilitation center,<br />

or an extended care facility (Table 2).<br />

Intermediate follow-up data was available for 45 (82%) of the<br />

55 patients (Table 3). More patients in the endoscopic group<br />

had residual <strong>cyst</strong>s than in the transcallosal craniotomy group,<br />

and there were no recurrences in either group (Fig. 2).<br />

However, fewer patients in the transcallosal craniotomy group<br />

underwent intermediate follow-up imaging (Table 3). Preoperative<br />

symptoms improved significantly in most patients,<br />

and overall neurological outcomes were similar in the two<br />

groups (Table 3).<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

To our knowledge, we present the largest comparison of<br />

endoscopic and transcallosal craniotomy for resection of third<br />

ventricular colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s. Two other small series have compared<br />

these techniques but small patient samples precluded adequate<br />

comparisons (28, 34). Although the types of complications differed<br />

in our two groups, the overall rates of complications were<br />

similar. The overall complication rate in the entire cohort (20<br />

out of 55 patients) was similar to other reported series (28, 34).<br />

TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR THIRD VENTRICULAR COLLOID CYSTS<br />

FIGURE 2. Kaplan-Meier plot demonstrating residual-free intervals<br />

between the transcallosal and endoscopic approaches. There was a significant<br />

difference in the intervals between the two groups (P � 0.05; χ 2 ).<br />

TABLE 3. Follow-up information of patients treated endoscopically<br />

and with a transcallosal craniotomy for resection of third<br />

ventricular colloid <strong>cyst</strong>sa Endoscopic Transcallosal<br />

(21/28) (24/27)<br />

Average follow-up (mean � SD ) 10.1 � 2.2 10.9 � 3.4<br />

Residual <strong>cyst</strong><br />

mo mo<br />

No residual (no./total) 53% (10/19) b 94% (16/17) b<br />

Small residual (no./total) 37% (7/19) b 6% (1/17) b<br />

Large residual (no./total) 11% (2/19) b 0% (0/17) b<br />

No scans performed (no./total)<br />

Neurological outcome<br />

2/21 7/24<br />

Improvement (no./total) 76% (16/21) 79% (19/24)<br />

Unchanged (no./total) 10% (2/21) 13% (3/24)<br />

Worsened (no./total) 14% (3/21) 8% (2/24)<br />

a SD, standard deviation.<br />

b P �0.05.<br />

Furthermore, there was no correlation between surgeons in<br />

terms of complication rates. Despite these complications, an<br />

overwhelming majority of patients recovered well enough to be<br />

discharged to home. All patients discharged to an extended<br />

care facility or rehabilitation facility had neurological symptoms<br />

at presentation.<br />

Not surprisingly, the length of hospitalization was slightly<br />

shorter in the endoscopic group than in the transcallosal craniotomy<br />

group. Although not specifically analyzed, this difference<br />

may translate to a more cost-effective treatment. However,<br />

caution is warranted because the rate of residual or recurrent<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s was higher in the endoscopic group during the intermediate<br />

follow-up period in these patients. Even after the most tech-<br />

NEUROSURGERY VOLUME 60 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2007 | 615

HORN ET AL.<br />

nically successful endoscopic procedures, these patients need<br />

close long-term follow-up if a residual <strong>cyst</strong> remains. We recommend<br />

MRI scanning 3 months after resection. If the <strong>cyst</strong> remains<br />

stable at least 4 years after resection, MRI scan studies can then<br />

be obtained at doubling intervals (i.e., 6 mo, 1 yr, 2 yr, etc.).<br />

Endoscopic Treatment<br />

Traditionally, colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle have been<br />

treated primarily through a transcortical or transcallosal craniotomy<br />

approach (17, 19, 21, 24, 27, 29, 37, 39, 43, 49, 51).<br />

Indeed, the transcallosal approach was the primary method<br />

used at our institution until the evolution of endoscopy<br />

enabled a viable alternative. Since its description in 1983 (46),<br />

the use of endoscopy for removing third ventricular colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s has gained popularity. Several series have demonstrated<br />

the efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s<br />

(1, 13–15, 23, 30, 36, 47).<br />

One criticism of the endoscopic approach is the decreased<br />

ability to resect <strong>cyst</strong>s completely compared with open<br />

approaches. In reality, the extent of resection varies widely from<br />

series to series. In one series, most of the 20 patients treated had<br />

residual <strong>cyst</strong>s (23). Only one patient in this series, however,<br />

needed a reoperation for recurrence 1 year after endoscopic<br />

treatment. In another large series, <strong>cyst</strong>s were resected completely<br />

in 80% of the patients treated via the <strong>endoscope</strong> (30).<br />

After an average follow-up period of 2 years, no patient with<br />

either total or subtotal resection developed symptomatic recurrence.<br />

In an earlier series, 12 out of 15 patients had residual<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>, but none needed reoperation (13). Likewise, our results<br />

demonstrated a high rate of residual <strong>cyst</strong>s (9 out of 21 <strong>cyst</strong>s),<br />

only two of which needed a reoperation for further resection.<br />

This finding highlights that, although an incomplete resection<br />

is acceptable, serial imaging and long-term follow-up periods<br />

are warranted. Because our follow-up period is relatively short,<br />

we cannot state definitively that the final recurrence rates in the<br />

two populations are significantly different. On the basis of our<br />

data, however, one can expect a higher rate of residual or recurrent<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s in the immediate postoperative period.<br />

Although the follow-up period in these series is relatively<br />

long, a longer follow-up period was recommended for each<br />

patient because the potential for regrowth after incomplete<br />

resection is unknown. Because there is a potential for rapid<br />

deterioration associated with devastating neurological morbidity<br />

or even death, close monitoring with MRI scan at progressively<br />

longer intervals is warranted (4, 7, 11, 17, 50). If complete<br />

resection is accomplished via the endoscopic approach, the<br />

schedule for follow-up imaging can be more relaxed.<br />

Despite being minimally invasive, endoscopy is still associated<br />

with complications. In fact, severe complications, such as<br />

hemiparesis and memory deficits, can occur (23, 30, 34). Of our<br />

endoscopic patients, two patients had permanent memory<br />

deficits (one mild and one severe) and one patient had moderate<br />

hemiparesis. Recently, we have used a shallower trajectory<br />

with a more lateral starting point. These modifications allow<br />

the <strong>endoscope</strong> to be positioned further inferior to the fornix.<br />

Significant traction on this structure is thereby avoided, and the<br />

risk for memory impairment should decrease. Newer technology<br />

in the design of <strong>endoscope</strong>s, including larger ports for<br />

instruments and wider-angle lenses, should help decrease the<br />

rate of residual <strong>cyst</strong>s. We are also now using a metal microtube<br />

to aid in the direct aspiration of the <strong>cyst</strong>. The key to this technique<br />

is that the rigidity of the tube allows significant negative<br />

pressure to develop to aspirate the highly viscous contents of<br />

the <strong>cyst</strong>.<br />

Open Craniotomy Approaches<br />

Since Dandy (12) first reported his results for the surgical<br />

treatment of third ventricular colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s, both the transcortical<br />

and transcallosal approaches have been widely used (10, 12,<br />

16, 19, 21, 24, 27, 37, 43, 49). When microsurgical techniques<br />

and contemporary imaging became available, the morbidity<br />

and mortality rates associated with these approaches decreased<br />

considerably (9, 29, 35, 39). Compared with endoscopic techniques,<br />

these approaches offer a better view and enable complete<br />

resection of <strong>cyst</strong>s. Some would argue, however, that an<br />

<strong>endoscope</strong> with angled optics can provide equal or better visualization<br />

of the <strong>cyst</strong>. There is little disagreement regarding the<br />

advantages of instrument manipulation during microsurgery<br />

compared with endoscopic surgery.<br />

Although the transcortical and transcallosal approaches have<br />

been reported to be relatively safe, they can still be associated<br />

with serious complications. One of our patients experienced a<br />

venous infarction after thrombosis from cortical veins and had<br />

residual neurological deficits. Other investigators have also<br />

reported this complication (20, 37). Although this type of complication<br />

would not occur in a transcortical approach, we prefer<br />

the transcallosal approach, which avoids damage to cortical<br />

tissue. When image guidance is used, however, a right frontal<br />

transcortical approach seems to be associated with a very low<br />

complication profile and is a reasonable alternative. In other<br />

series, use of transcallosal or transcortical approaches has also<br />

been associated with memory impairment (3, 25, 26, 37, 40).<br />

Even with the risk of complications associated with the transcallosal<br />

approach, the reoperation rate for residual <strong>cyst</strong>s was<br />

zero. This is an important difference compared with the endoscopic<br />

approach, in which residual <strong>cyst</strong>s are common. At this<br />

time, to our knowledge, there are no adequate preoperative<br />

predictors of success using endoscopy for colloid <strong>cyst</strong> resection.<br />

Until this issue is thoroughly analyzed, surgeons and patients<br />

must accept the possibility that another surgical procedure may<br />

be needed to achieve a cure after an endoscopic approach.<br />

Alternative Treatments<br />

Several alternatives to the transcallosal/transventricular<br />

craniotomy or endoscopic approach exist for the resection of<br />

colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s. These options include conservative observation,<br />

isolated ventriculoperitoneal shunting, and infratentorial<br />

supracerebellar approaches (16, 24, 33). Conservative therapy<br />

has been advocated for older, asymptomatic patients who do<br />

not display ventriculomegaly (44, 45). However, this treatment<br />

is controversial, considering the many case reports of sudden<br />

616 | VOLUME 60 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2007 www.neurosurgery-online.com

deterioration and death caused by rapidly enlarging <strong>cyst</strong>s (4, 7,<br />

11, 17, 50).<br />

A stereotactically placed tube retractor has been used to create<br />

a minimally invasive transventricular approach (2, 5, 8, 32). This<br />

approach is a compromise between the small aperture available<br />

with endoscopy and the greater maneuverability associated with<br />

microsurgery. Although these series report good success rates,<br />

the technique requires a larger corticectomy than endoscopy and<br />

more limited working angles than open microsurgery.<br />

Since its description in 1978 (5), aspiration of the <strong>cyst</strong> using<br />

stereotactic needles has also been studied extensively. Early<br />

reports showed promising results, but the rate of residual and<br />

recurrent <strong>cyst</strong>s was unacceptably high in subsequent studies<br />

(22, 31, 38, 41, 42, 48). Although two studies identified imaging<br />

factors that helped predict success with this technique, it has<br />

now largely been replaced by endoscopy (18, 31).<br />

CONCLUSIONS<br />

The use of the <strong>endoscope</strong> to remove colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s in the third<br />

ventricle is a safe and effective approach compared with transcallosal<br />

craniotomy. The endoscopic approach is associated<br />

with a shorter operative time, shorter hospital stay, and lower<br />

infection rate than the transcallosal approach. However, more<br />

patients treated endoscopically needed a reoperation for residual<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>. On the basis of these results, the <strong>endoscope</strong> can be<br />

considered as a first-line treatment for these lesions, with the<br />

understanding that a small number of these patients may need<br />

a transcallosal craniotomy to remove residual <strong>cyst</strong>s.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. Abdou MS, Cohen AR: Endoscopic treatment of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third<br />

ventricle. Technical note and review of the literature. J Neurosurg<br />

89:1062–1068, 1998.<br />

2. Abernathey CD, Davis DH, Kelly PJ: Treatment of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third<br />

ventricle by stereotaxic microsurgical laser craniotomy. J Neurosurg<br />

70:525–529, 1989.<br />

3. Aggleton JP, McMackin D, Carpenter K, Hornak J, Kapur N, Halpin S, Wiles<br />

CM, Kamel H, Brennan P, Carton S, Gaffan D: Differential cognitive effects of<br />

colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s in the third ventricle that spare or compromise the fornix. Brain<br />

123:800–815, 2000.<br />

4. Aronica PA, Ahdab-Barmada M, Rozin L, Wecht CH: Sudden death in an adolescent<br />

boy due to a colloid <strong>cyst</strong> of the third ventricle. Am J Forensic Med<br />

Pathol 19:119–122, 1998.<br />

5. Barlas O, Karadereler S: Stereotactically guided microsurgical removal of colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 146:1199–1204, 2004.<br />

6. Batnitzky S, Sarwar M, Leeds NE, Schechter MM, Azar-Kia B: <strong>Colloid</strong> <strong>cyst</strong>s<br />

of the third ventricle. Radiology 112:327–341, 1974.<br />

7. Buttner A, Winkler PA, Eisenmenger W, Weis S: <strong>Colloid</strong> <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle<br />

with fatal outcome: A report of two cases and review of the literature.<br />

Int J Legal Med 110:260–266, 1997.<br />

8. Cabbell KL, Ross DA: Stereotactic microsurgical craniotomy for the treatment<br />

of third ventricular colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s. Neurosurgery 38:301–307, 1996.<br />

9. Cairns H, Mosberg WH Jr: <strong>Colloid</strong> <strong>cyst</strong> of the third ventricle. Surg Gynecol<br />

Obstet 92:545–570, 1951.<br />

10. Camacho A, Abernathey CD, Kelly PJ, Laws ER Jr: <strong>Colloid</strong> <strong>cyst</strong>s: Experience<br />

with the management of 84 cases since the introduction of computed tomography.<br />

Neurosurgery 24:693–700, 1989.<br />

11. Chan RC, Thompson GB: Third ventricular colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s presenting with<br />

acute neurological deterioration. Surg Neurol 19:358–362, 1983.<br />

TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR THIRD VENTRICULAR COLLOID CYSTS<br />

12. Dandy WE: Benign Tumors of the Third Ventricle of the Brain: Diagnosis and<br />

Treatment. Springfield, Charles C. Thomas, 1933.<br />

13. Decq P, Le Guerinel C, Brugieres P, Djindjian M, Silva D, Keravel Y, Melon E,<br />

Nguyen JP: Endoscopic management of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s. Neurosurgery<br />

42:1288–1296, 1998.<br />

14. Deinsberger W, Boker DK, Bothe HW, Samii M: Stereotactic endoscopic treatment<br />

of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle. Acta Neurochir (Wien)<br />

131:260–264, 1994.<br />

15. Deinsberger W, Boker DK, Samii M: Flexible <strong>endoscope</strong>s in treatment<br />

of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle. Minim Invasive Neurosurg<br />

37:12–16, 1994.<br />

16. Desai KI, Nadkarni TD, Muzumdar DP, Goel AH: Surgical management of<br />

colloid <strong>cyst</strong> of the third ventricle—A study of 105 cases. Surg Neurol<br />

57:295–304, 2002.<br />

17. de Witt Hamer PC, Verstegen MJ, De Haan RJ, Vandertop WP, Thomeer RT,<br />

Mooij JJ, van Furth WR: High risk of acute deterioration in patients harboring<br />

symptomatic colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle. J Neurosurg<br />

96:1041–1045, 2002.<br />

18. El Khoury C, Brugieres P, Decq P, Cosson-Stanescu R, Combes C, Ricolfi F,<br />

Gaston A: <strong>Colloid</strong> <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle: Are MR imaging patterns predictive<br />

of difficulty with percutaneous treatment? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol<br />

21:489–492, 2000.<br />

19. Fritsch H: <strong>Colloid</strong> <strong>cyst</strong>s—A review including 19 own cases. Neurosurg Rev<br />

11:159–166, 1988.<br />

20. Garrido E, Fahs GR: Cerebral venous and sagittal sinus thrombosis after<br />

transcallosal removal of a colloid <strong>cyst</strong> of the third ventricle: Case report.<br />

Neurosurgery 26:540–542, 1990.<br />

21. Gokalp HZ, Yuceer N, Arasil E, Erdogan A, Dincer C, Baskaya M: <strong>Colloid</strong> <strong>cyst</strong><br />

of the third ventricle. Evaluation of 28 cases of colloid <strong>cyst</strong> of the third ventricle<br />

operated on by transcortical transventricular (25 cases) and transcallosal/transventricular<br />

(3 cases) approaches. Acta Neurochir (Wien)<br />

138:45–49, 1996.<br />

22. Hall WA, Lunsford LD: Changing concepts in the treatment of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s.<br />

An 11-year experience in the CT era. J Neurosurg 66:186–191, 1987.<br />

23. Hellwig D, Bauer BL, Schulte M, Gatscher S, Riegel T, Bertalanffy H:<br />

Neuroendoscopic treatment for colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle: The experience<br />

of a decade. Neurosurgery 52:525–533, 2003.<br />

24. Hernesniemi J, Leivo S: Management outcome in third ventricular colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s in a defined population: A series of 40 patients treated mainly by transcallosal<br />

microsurgery. Surg Neurol 45:2–14, 1996.<br />

25. Hodges JR, Carpenter K: Anterograde amnesia with fornix damage following<br />

removal of IIIrd ventricle colloid <strong>cyst</strong>. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry<br />

54:633–638, 1991.<br />

26. Jeeves MA, Simpson DA, Geffen G: Functional consequences of the transcallosal<br />

removal of intraventricular tumours. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry<br />

42:134–142, 1979.<br />

27. Jeffree RL, Besser M: <strong>Colloid</strong> <strong>cyst</strong> of the third ventricle: A clinical review of 39<br />

cases. J Clin Neurosci 8:328–331, 2001.<br />

28. Kehler U, Brunori A, Gliemroth J, Nowak G, Delitala A, Chiappetta F, Arnold<br />

H: Twenty colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s—Comparison of endoscopic and microsurgical management.<br />

Minim Invasive Neurosurg 44:121–127, 2001.<br />

29. Kelly R: <strong>Colloid</strong> <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle; Analysis of twenty-nine cases.<br />

Brain 74:23–65, 1951.<br />

30. King WA, Ullman JS, Frazee JG, Post KD, Bergsneider M: Endoscopic resection<br />

of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s: Surgical considerations using the rigid <strong>endoscope</strong>.<br />

Neurosurgery 44:1103–1111, 1999.<br />

31. Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD: Stereotactic management of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s:<br />

Factors predicting success. J Neurosurg 75:45–51, 1991.<br />

32. Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD: Microsurgical resection of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s using a<br />

stereotactic transventricular approach. Surg Neurol 46:485–492, 1996.<br />

33. Konovalov AN, Pitskhelauri DI: Infratentorial supracerebellar approach to<br />

the colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle. Neurosurgery 49:1116–1123, 2001.<br />

34. Lewis AI, Crone KR, Taha J, van Loveren HR, Yeh HS, Tew JM Jr: Surgical<br />

resection of third ventricle colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s. Preliminary results comparing transcallosal<br />

microsurgery with endoscopy. J Neurosurg 81:174–178, 1994.<br />

35. Little JR, MacCarty CS: <strong>Colloid</strong> <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle. J Neurosurg<br />

40:230–235, 1974.<br />

NEUROSURGERY VOLUME 60 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2007 | 617

HORN ET AL.<br />

36. Longatti P, Martinuzzi A, Moro M, Fiorindi A, Carteri A: Endoscopic treatment<br />

of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle: 9 consecutive cases. Minim<br />

Invasive Neurosurg 43:118–123, 2000.<br />

37. Mathiesen T, Grane P, Lindgren L, Lindquist C: Third ventricle colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s:<br />

A consecutive 12-year series. J Neurosurg 86:5–12, 1997.<br />

38. Mathiesen T, Grane P, Lindquist C, von Holst H: High recurrence rate following<br />

aspiration of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s in the third ventricle. J Neurosurg 78:748–752, 1993.<br />

39. McKissock W: The surgical treatment of colloid <strong>cyst</strong> of the third ventricle; A<br />

report based upon twenty-one personal cases. Brain 74:1–9, 1951.<br />

40. McMackin D, Cockburn J, Anslow P, Gaffan D: Correlation of fornix damage<br />

with memory impairment in six cases of colloid <strong>cyst</strong> removal. Acta Neurochir<br />

(Wien) 135:12–18, 1995.<br />

41. Mohadjer M, Teshmar E, Mundinger F: CT-stereotaxic drainage of colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s in the foramen of Monro and the third ventricle. J Neurosurg<br />

67:220–223, 1987.<br />

42. Musolino A, Munari C, Fosse S, Blond S, Betti O, Daumas-Duport C,<br />

Chodkiewicz JP: Stereotactic aspiration of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle.<br />

Preliminary report. Appl Neurophysiol 50:210–217, 1987.<br />

43. Nitta M, Symon L: <strong>Colloid</strong> <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle. A review of 36 cases.<br />

Acta Neurochir (Wien) 76:99–104, 1985.<br />

44. Pollock BE, Huston J 3rd: Natural history of asymptomatic colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the<br />

third ventricle. J Neurosurg 91:364–369, 1999.<br />

45. Pollock BE, Schreiner SA, Huston J 3rd: A theory on the natural history of colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle. Neurosurgery 46:1077–1083, 2000.<br />

46. Powell MP, Torrens MJ, Thomson JL, Horgan JG: Isodense colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the<br />

third ventricle: A diagnostic and therapeutic problem resolved by ventriculoscopy.<br />

Neurosurgery 13:234–237, 1983.<br />

47. Rodziewicz GS, Smith MV, Hodge CJ Jr: Endoscopic colloid <strong>cyst</strong> surgery.<br />

Neurosurgery 46:655–662, 2000.<br />

48. Skirving DJ, Pell MF: Early recurrence from stereotactic aspiration of a colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong> of the third ventricle. J Clin Neurosci 8:570–571, 2001.<br />

49. Solaroglu I, Beskonakli E, Kaptanoglu E, Okutan O, Ak F, Taskin Y:<br />

Transcortical-transventricular approach in colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle:<br />

Surgical experience with 26 cases. Neurosurg Rev 27:89–92, 2004.<br />

50. Torrey J: Sudden death in an 11-year-old boy due to rupture of a colloid <strong>cyst</strong> of<br />

the third ventricle following ‘disco-dancing.’ Med Sci Law 23:114–116, 1983.<br />

51. Villani R, Papagno C, Tomei G, Grimoldi N, Spagnoli D, Bello L: Transcallosal<br />

approach to tumors of the third ventricle. Surgical results and neuropsychological<br />

evaluation. J Neurosurg Sci 41:41–50, 1997.<br />

COMMENTS<br />

Horn et al. have retrospectively reviewed the institutional experience<br />

of surgically treated third ventricle colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s at the Barrow<br />

Neurological Institute between 1994 and 2004. Fifty-five patients were<br />

treated; of these, follow-up data was available for 45 patients. Twentyeight<br />

patients underwent endoscopic and 27 underwent transcallosal<br />

microsurgical procedures. The follow-up period ranged from 1 to 54<br />

months. Thus, it is necessary to find the patients who were lost to follow-up<br />

to rule out recurrences and residuals and to follow all patients<br />

for a much longer period of time. A mean follow-up period of less<br />

than 1 year is not satisfactory, particularly because a large fraction of<br />

the patients had residual <strong>cyst</strong>. <strong>Colloid</strong> <strong>cyst</strong>s remain important to diagnose<br />

and treat, and the mortality and morbidity rates from delayed<br />

diagnoses are considerable (2, 4).<br />

However, I feel that this is still an important contribution. It provides<br />

an attempt at comparing two different surgical therapies and, thus, is<br />

important for many reasons. The authors are to be commended for<br />

their honest report. It is, however, difficult to follow the reasoning<br />

behind their conclusions. Their data showed that endoscopy at their<br />

center was inferior to transcallosal surgery: A residual <strong>cyst</strong> was<br />

detectable in nine out of 21 patients after endoscopic surgery. The reasoning<br />

that only a fraction of patients with residuals needed surgery is<br />

misleading because the need for operation of a potentially growing<br />

residual can only be assessed after a true long-term follow-up period<br />

(4). Repeated surgery and the frequent magnetic resonance imaging follow-up<br />

examinations recommended for the failures would rapidly nullify<br />

and reverse any economic gain from the shorter operative time<br />

and hospital. The complications after endoscopy included severe memory<br />

deficit and hemiparesis, whereas transcallosal surgery led to reoperation<br />

for surgical complications or epilepsy. Thus, the complication<br />

rate was higher than expected in both groups. Today, it is reasonable to<br />

expect cure from a colloid <strong>cyst</strong> (3, 5, 6) without permanent morbidity<br />

from the treatment (1, 3, 5, 6). We have had one radiologically visible<br />

residual and no severe complications in our transcallosal <strong>cyst</strong> surgery<br />

series, which now includes 37 patients. The residual we observed was<br />

early in the series. Meticulous microsurgery allows preservation of<br />

bridging veins, avoidance of cortical and forniceal damage, radical <strong>cyst</strong><br />

removal, and minimal bleeding. Postoperative drainage or shunting is<br />

usually not necessary when hemorrhage is well controlled.<br />

It was surprising that as many as eight different surgeons had taken<br />

part in the surgical treatment. Given this, each would have operated on<br />

an average of less than 0.7 patients annually. This may be one reason<br />

for the high complication rate and low grade of tumor control. One of<br />

the findings in the institutional series (5) was that all serious complications<br />

occurred to the few surgeons who had limited exposure to third<br />

ventricular surgery. It is probable that concentration of sensitive surgery<br />

would allow improved results.<br />

It is important to observe that, although the trial design allowed a<br />

comparison of two treatment modes, which is in agreement with the<br />

reasoning behind evidence-based medicine, a major caveat in the comparison<br />

is that the results were worse than expected with both treatment<br />

modes. It is questionable whether or not the comparison can be<br />

generalized under such conditions. My conclusion, which is at variance<br />

with the authors, is that the data indicate that transcallosal surgery<br />

was a better treatment than endoscopic surgery and that total outcomes<br />

may have been better if only one treatment mode was used by<br />

a limited number of surgeons.<br />

Tiit Mathiesen<br />

Stockholm, Sweden<br />

1. Decq P, Le Guerinel C, Brugieres P, Djindjian M, Silva D, Keravel Y, Melon E,<br />

Nguyen JP: Endoscopic management of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s. Neurosurgery<br />

42:1288–1296, 1998.<br />

2. De Witt Hamer PC, Verstegen MJ, De Haan RJ, Vandertop WP, Thomeer RT,<br />

Mooij JJ, van Furth WR: High risk of acute deterioration in patients harboring<br />

symptomatic colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle. J Neurosurg 96:1041–1045,<br />

2002.<br />

3. Hernesniemi J, Leivo S: Management outcome in third ventricular colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s in a defined population: A series of 40 patients treated mainly by transcallosal<br />

microsurgery. Surg Neurol 45:2–14, 1996.<br />

4. Mathiesen T, Grane P, Lindquist C, von Holst H: High recurrence rate following<br />

aspiration of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s in the third ventricle. J Neurosurg 78:748–752,<br />

1993.<br />

5. Mathiesen T, Grane P, Lindgren L, Lindquist C: Third ventricle colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s:<br />

A consecutive 12-year series. J Neurosurg 86:5–12, 1997.<br />

6. Teo C: Complete endoscopic removal of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s: Issues of safety and efficacy.<br />

Neurosurg Focus 6:e9, 1999.<br />

The authors compared outcomes after transcallosal resection or endoscopic-assisted<br />

transcortical resection for patients with colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s.<br />

As might be expected, endoscopic surgeries were associated with a<br />

higher rate for subtotal <strong>cyst</strong> removal, in which a small remnant was<br />

left. There was no significant difference in results, and the surgeons in<br />

this group who performed the transcallosal surgeries apparently continue<br />

to do so. I have long thought that this surgery is best performed<br />

618 | VOLUME 60 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2007 www.neurosurgery-online.com

y a surgeon who is particularly comfortable with his or her chosen<br />

approach. Given the chance for cognitive or other functional morbidity,<br />

it is not surprising that neurosurgeons would not be quick to<br />

embark on a new surgical strategy. At our institution, stereotactic<br />

transcortical microsurgical resection has evolved into stereotactic<br />

transcortical endoscopic-associated resection for many patients. We<br />

continue to use standard microsurgical instruments for both<br />

approaches. How surgeons will use the information provided in this<br />

report will be interesting. Will they change their route down to the<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>? Will they change their technique for magnification and illumination<br />

of the surgical field?<br />

Douglas Kondziolka<br />

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania<br />

Discussions regarding the management of patients with colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s<br />

clearly demonstrate that there is an inverse relationship between<br />

the frequency of a disorder and the certainty surgeons express about<br />

the best method by which to treat it. Consequently, most case series on<br />

colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s conclude that a particular surgical approach is superior to<br />

other alternatives, although the number of patients undergoing operation<br />

is generally small, and there is often no reliable control group<br />

available for comparison. In this retrospective study of patients with<br />

mostly symptomatic colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s (only 9% were asymptomatic), the<br />

authors report that endoscopic removal of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s was safe with<br />

outcomes equal or slightly better when compared with patients undergoing<br />

a transcallosal resection. Strengths of this study include a relatively<br />

large number of patients (n = 55) and the similarity of the two<br />

groups with regard to age, symptoms, <strong>cyst</strong> size, and presence of hydrocephalus.<br />

Notably, more patients had a small residual <strong>cyst</strong> after endoscopic<br />

removal. The follow-up period is not sufficient to conclude that<br />

the symptomatic recurrence rates will be equivalent at a later date.<br />

After reviewing the experience at our center on the presentation and<br />

natural history of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s (1, 2), I have developed some thoughts<br />

about this problem that are not generally appreciated. First, a percentage<br />

of well informed patients with asymptomatic colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s can be safely<br />

managed with observation and serial imaging. However, before this can<br />

be recommended, it must be clearly established that the patient is without<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>-related symptoms, which is ideally confirmed through repeated<br />

examinations by more than one neurosurgeon or neurologist. In addition,<br />

these patients must understand that they have a potentially lethal<br />

condition if they become symptomatic and do not seek or have access to<br />

immediate medical attention. Second, referral of patients with newly<br />

diagnosed colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s to tertiary care centers makes medicolegal sense<br />

for many neurosurgeons, with the exception being patients presenting<br />

with progressive symptoms and acute hydrocephalus. For such patients,<br />

placement of an external ventricular drain with appropriate transfer<br />

after the patient has been stabilized is a very reasonable approach.<br />

Several times each year since the publication of my studies, I have been<br />

asked to review cases to determine whether or not surgery should have<br />

been performed; if surgery was performed, I am asked whether or not<br />

the neurosurgeon was qualified to perform such a rare surgery. In fact, I<br />

would speculate that the incidence of lawsuits arising from the management<br />

and surgery of patients with colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s is higher than practically<br />

any other condition affecting the nervous system of adults.<br />

Bruce E. Pollock<br />

Rochester, Minnesota<br />

1. Pollock BE, Huston J 3rd: Natural history of asymptomatic, untreated colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle. J Neurosurg 91:364–369, 1999.<br />

TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR THIRD VENTRICULAR COLLOID CYSTS<br />

2. Pollock BE, Schriener S, Huston J 3rd: A theory on the natural history of colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s of the third ventricle. Neurosurgery 46:1077–1083, 2000.<br />

Iwould expect that there will be an ongoing debate for years to come<br />

concerning the relative merits of endoscopic compared with microsurgical<br />

removal of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s. This dispute will cease only when follow-up<br />

intervals of 10 years or greater are available for a substantial<br />

number of patients who have undergone endoscopic resection. Horn et<br />

al., however, have demonstrated reduced operative time and hospital<br />

stay with endoscopic removal of colloid <strong>cyst</strong>s, disparities that will not<br />

be influenced by longer follow-up periods. These differences have also<br />

been shown in previously published retrospective series and are, therefore,<br />

not debated. Certain benefits of endoscopic colloid <strong>cyst</strong> resection<br />

are, therefore, irrefutable.<br />

Although the degree of resection is important in colloid <strong>cyst</strong><br />

removal, it would be simplistic to gauge successful surgery on the<br />

presence of residual <strong>cyst</strong> after endoscopic removal. Incomplete colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong> resection admittedly occurs more frequently and is actually considered<br />

preferable in some circumstances in endoscopic resection.<br />

However, one needs to be diligent in the interpretation of “residual colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>.” There is substantial difference between magnetic resonance<br />

imaging-defined residual disease and <strong>cyst</strong> wall remnants that are seen<br />

at the time of endoscopic removal. In endoscopic colloid <strong>cyst</strong> removal,<br />

any adherent <strong>cyst</strong> wall remnants after complete <strong>cyst</strong> evacuation should<br />

be extirpated with coagulation, a technical advantage that was not possible<br />

with stereotactic aspiration. These “endoscopic” remnants are<br />

commonly, but probably inaccurately, referenced as the cause of higher<br />

recurrence rates in endoscopic resection.<br />

In this work by Horn et al., it is uncertain if the two patients who<br />

first had an endoscopic removal underwent a second procedure for<br />

residual colloid <strong>cyst</strong> (<strong>cyst</strong> wall and contents) or “endoscopic” remnants<br />

(coagulated <strong>cyst</strong> wall). What is clear is that no patient in either group<br />

experienced radiographic or clinical progression. Furthermore, there is<br />

no mention regarding the interval of time between the two procedures.<br />

As a result, it remains inconclusive whether or not recurrence rates are<br />

greater in patients undergoing endoscopic removal. It will be prudent<br />

to include accurate assessments of degree of resection and longer follow-up<br />

intervals in subsequent works.<br />

Surgical morbidity and extent of resection will always be influenced<br />

by experience. The current work represents preeminent surgeons<br />

in both endoscopic and microsurgical surgery, and serves as<br />

testimony of the difficulty in defining either method as superior. At<br />

this time, the best management scheme for colloid <strong>cyst</strong> resection is<br />

defined by surgeon ability, equipment availability, and symptom<br />

presentation. With that being said, the recognized benefits of endoscopic<br />

surgery demand that the technique continue to be refined<br />

such that the ultimate outcome is as good as or better than conventional<br />

surgical techniques.<br />

Mark M. Souweidane<br />

New York, New York<br />

The authors retrospectively compare their institution’s results of<br />

open microsurgical resection versus endoscopic resection for colloid<br />

<strong>cyst</strong>s. Although several studies have addressed this topic, this is one of<br />

the largest series and comes out of an institution with expertise in both<br />

techniques. Despite the large number of patients in this series, the issue<br />

of which procedure is best has not been completely resolved. The comparison<br />

is compromised by its retrospective analysis, inclusion of multiple<br />

surgeons, and a limited follow-up period. The overall high complication<br />

rate of 36% underscores the precarious nature of these lesions<br />

NEUROSURGERY VOLUME 60 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2007 | 619

HORN ET AL.<br />

and why a strong argument can be made for conservative management<br />

of incidental lesions.<br />

The comparison trade-off is between completeness of resection and<br />

complications. The microsurgical group had a higher incidence of infections<br />

(19 versus 0%) and need for shunting (19 versus 0%). The incidence<br />

of neurological complications was similar in both groups (11%).<br />

However, the endoscopic group had a higher incidence of incomplete<br />

resection (47 versus 6%). Among patients with residual <strong>cyst</strong>s who did<br />

not undergo reoperation, it is unknown whether or not additional<br />

intervention will be needed in the future and how this would influence<br />

the outcome analysis.<br />

It is not surprising that, among patients whose treatments were<br />

uncomplicated, the endoscopic group had shorter hospital and intensive<br />

care unit stays. As the endoscopic versus craniotomy controversy<br />

has evolved, it seems that endoscopic surgery is a viable option, and<br />

experienced endoscopic surgeons are likely to experience good outcomes.<br />

Surgeons not experienced in endoscopy should not be misled,<br />

however. Endoscopic resection of a colloid <strong>cyst</strong> requires a sophisticated<br />

level of expertise if favorable results are to be achieved.<br />

Jeffrey N. Bruce<br />

New York, New York<br />

Wilhelm Braune. 1831–1892. Topographisch-anatomischer Atlas, nach Durchschnitten an gefrornen Cadavern. Leipzig: Verlag von Veit & Comp.,<br />

1867–1872. (Courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland).<br />

620 | VOLUME 60 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2007 www.neurosurgery-online.com