The German Law Journal

The German Law Journal

The German Law Journal

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

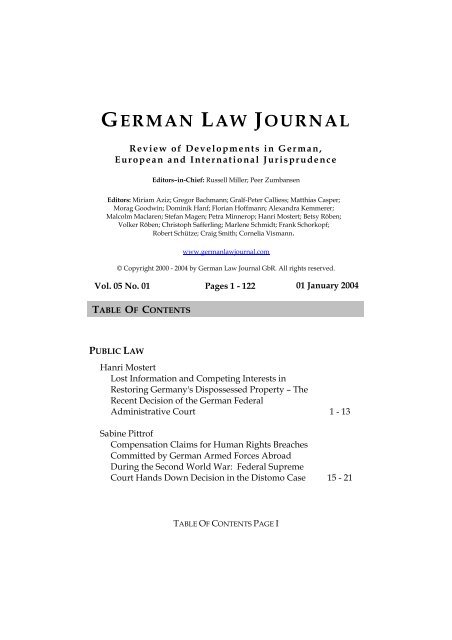

GERMAN LAW JOURNAL<br />

Review of Developments in <strong>German</strong>,<br />

European and International Jurisprudence<br />

Editors–in-Chief: Russell Miller; Peer Zumbansen<br />

Editors: Miriam Aziz; Gregor Bachmann; Gralf-Peter Calliess; Matthias Casper;<br />

Morag Goodwin; Dominik Hanf; Florian Hoffmann; Alexandra Kemmerer;<br />

Malcolm Maclaren; Stefan Magen; Petra Minnerop; Hanri Mostert; Betsy Röben;<br />

Volker Röben; Christoph Safferling; Marlene Schmidt; Frank Schorkopf;<br />

Robert Schütze; Craig Smith; Cornelia Vismann.<br />

www.germanlawjournal.com<br />

© Copyright 2000 - 2004 by <strong>German</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> GbR. All rights reserved.<br />

Vol. 05 No. 01 Pages 1 - 122 01 January 2004<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

PUBLIC LAW<br />

Hanri Mostert<br />

Lost Information and Competing Interests in<br />

Restoring <strong>German</strong>y's Dispossessed Property – <strong>The</strong><br />

Recent Decision of the <strong>German</strong> Federal<br />

Administrative Court<br />

Sabine Pittrof<br />

Compensation Claims for Human Rights Breaches<br />

Committed by <strong>German</strong> Armed Forces Abroad<br />

During the Second World War: Federal Supreme<br />

Court Hands Down Decision in the Distomo Case<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I<br />

1 - 13<br />

15 - 21

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

PRIVATE LAW<br />

Florian Mächtel<br />

<strong>The</strong> Defence of “Change of Position” in English<br />

and <strong>German</strong> <strong>Law</strong> of Unjust Enrichment<br />

EUROPEAN & INTERNATIONAL LAW<br />

Stefan Kirchner<br />

Relative Normativity and the Constitutional<br />

Dimension of International <strong>Law</strong>: A Place for<br />

Fundamental Rules and Values in the International<br />

Legal System<br />

Geo Quinot<br />

Substantive Legitimate Expectations in South<br />

African and European Administrative <strong>Law</strong><br />

Vanessa Hernández Guerrero<br />

Defining the Balance between Free Competition<br />

and Tax Sovereignty in EC and WTO <strong>Law</strong>: <strong>The</strong><br />

“due respect” to the General Tax System<br />

LEGAL CULTURE<br />

Andreas Abegg and Annemarie Thatcher<br />

Book Review – Freedom of Contract in the 19 th<br />

Century: Mythology and the Silence of the Sources<br />

– Sibylle Hofer’s Freiheit ohne Grenzen?<br />

Privatrechtstheoretische Diskussionen im 19.<br />

Jahrhundert<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE II<br />

23 - 46<br />

47 - 64<br />

65 - 85<br />

87 - 100<br />

101 - 114

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Friedemann Kiethe<br />

Book Review - Gunther Mävers’ Die<br />

Mitbestimmung der Arbeitnehmer in der<br />

Europäischen Aktiengesellschaft (Employee’s<br />

Participation in the European Stock Company)<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE III<br />

115 - 122

PUBLIC LAW<br />

Lost Information and Competing Interests in Restoring<br />

<strong>German</strong>y’s Dispossessed Property – <strong>The</strong> Recent Decision<br />

of the <strong>German</strong> Federal Administrative Court<br />

By Hanri Mostert *<br />

A. Introduction<br />

With the progressive "accession" of the <strong>German</strong> Democratic Republic to the Federal<br />

<strong>German</strong> Republic after the reunification in 1990, <strong>German</strong>y had to deal with a number<br />

of impediments emanating from the attempt to reconcile different political,<br />

social and legal models that developed during the forty years of separation between<br />

East and West <strong>German</strong>y. Among these was the issue of how the property<br />

order in <strong>German</strong>y would be influenced by seeking to integrate two such different<br />

socio-political and legal systems. 1 As the discussion below indicates, the demands<br />

placed by this issue on the courts, legislature and administration of the newly reunified<br />

Federal <strong>German</strong> Republic still cause repercussions.<br />

* Associate Professor, Faculty of <strong>Law</strong>, Stellenbosch University, South Africa. hmos@sun.ac.za. I am grateful<br />

to Stefan Häußler, who clarified some of the finer detail in the <strong>German</strong> text of the Federal Administrative<br />

Court’s decision for me, and to the Max Planck Institute for International and Foreign Public <strong>Law</strong><br />

in Heidelberg, for making available their library facilities to me. <strong>The</strong> financial assistance of the National<br />

Research Foundation and the University of Stellenbosch is hereby gratefully acknowledged. Opinions<br />

expressed in this case discussion should not be attributed to either of these institutions.<br />

1 See inter alia: O. Depenheuer Eigentum und Rechtsstaat NEUE JURISTISCHE WOCHENSCHRIFT 53 (2000) 6,<br />

p. 385–390; R. Meixner Entscheidung des Bundesverfassungsgerichts zum Entschädigungs- und Ausgleichsleistungsgesetz<br />

DIE ÖFFENTLICHE VERWALTUNG 55 (2002) 21, p. 900-908; K-A. Schwarz Wiedergutmachung und<br />

die "exceptio pecuniam non habendi" DIE ÖFFENTLICHE VERWALTUNG 53 (2000) 17, p. 721-729; A. Jaekel Zur<br />

Rechtsprechung des Bundesverwaltungsgerichts zu den Überschuldungsfällen ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR VERMÖGENS-<br />

UND INVESTITIONSRECHT 6 (1996) 3, p. 113-117; T. Schweisfurth Von der Völkerrechtswidrigkeit der SBZ-<br />

Konfiskationen 1945-1949 zur Verfassungswidrigkeit des Restitutionsausschlusses 1990, ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR<br />

VERMÖGENS- UND INVESTITIONSRECHT 10 (2000) 9, p. 505-521; and generally also T. Schweisfurth SBZ-<br />

KONFISKATIONEN PRIVATEN EIGENTUMS 1945 BIS 1949, Baden-Baden, Nomos (2000). P.E. Quint THE<br />

IMPERFECT UNION - CONSTITUTIONAL STRUCTURES OF GERMAN UNIFICATION, Princeton, Princeton Univ.<br />

Press, (1997) deals with the intricacies of the Re-unification in particular.

2 G ERMAN L AW J OURNAL [Vol. 05 No. 01<br />

One such problem relates to the extent to which the reparation arrangements in<br />

West <strong>German</strong>y influenced the measures undertaken in East <strong>German</strong>y. Refugees<br />

who left <strong>German</strong>y between 1933 and 1945 were forced to sell their immovable<br />

property and could only take a restricted amount of currency out of the country. 2<br />

<strong>The</strong> persecuted that did not flee only rarely survived the large-scale massacre of socalled<br />

"state enemies" during the National Socialist reign of terror that persisted<br />

through the end of World War II. 3 In both cases, the victims’ land often ended up in<br />

the hands of Nazi Party organizations or members, without any systematic alterations<br />

to the land register. 4 <strong>The</strong> Wiedergutmachung initiative in the <strong>German</strong> Federal<br />

Republic was aimed at providing some kind of reparation for these victims of National<br />

Socialism. 5 <strong>The</strong> Bundesgerichtshof (BGH – Federal Court of Justice) declared<br />

on one occasion that these reparation arrangements were compatible with article<br />

14 of the Basic <strong>Law</strong>. 6<br />

No comprehensive rehabilitation was ever envisaged in the <strong>German</strong> Democratic<br />

Republic for the victims of National Socialism, 7 and in particular no restitution of<br />

2 M. Southern Restitution or Compensation: <strong>The</strong> Land Question in East <strong>German</strong>y 1993 INT. & COMP. L.Q 690 at<br />

691.<br />

3 Id.<br />

4 Id.<br />

5 <strong>The</strong> Wiedergutmachung initiative did not incorporated only a reparations program for dispossessed<br />

property. Instead, it constituted a full-blown attempt to induce social change in <strong>German</strong>y, dealing with<br />

“denazification” and reform of the civil service over and above its attempts to restore property. It is<br />

outside the scope of this discussion to undertake an extensive discussion of this initiative, or even to list<br />

comprehensively the legislative and administrative measures applied to this initiative. For more detail,<br />

see esp. C. Goschler WIEDERGUTMACHUNG – WESTDEUTSCHLAND UND DIE VERFOLGTEN DES<br />

NATIONALSOZIALISMUS (1945-1954) Munich, R. Oldenbourg Verlag (1992); and the case study of National-Socialist<br />

induced dispossession of Jewish property in the Rhineland-Palatinate between 1938 and<br />

1953 as documented by W. Rummel & J. Rath “DEM REICH VERFALLEN – DEN BERECHTIGTEN<br />

ZURÜCKZUERSTATTEN” Koblenz, Verlag der Landesarchivverwaltung Rheinland-Pfalz (2001). A commentary<br />

on the most important laws behind the Wiedergutmachung initiative, e.g. the Bundesgesetz zur<br />

Entschädigung für Opfer der nationalsozialistischen Verfolgung (Federal Act for Compensation of Victims of<br />

National-Socialism); Gesetze zur Regelung der Wiedergutmachung nationalsozialistischen Unrechts für Angehörige<br />

des öffentlichen Dienstes im Inland und im Ausland (Acts for the Regulation of the Reparation of<br />

National-Socialist Injustice for Foreign and Inner Civil Servants), and Gesetze zur Wiedergutmachung<br />

nationalisozialistischen Unrechts in der Kriegsopferversorgung für Berechtigte im Inland und im Ausland (Acts<br />

for the Reparation of National-Socialist Injustice in the Care of Entitled Victims of War), see H-G. Ehrig<br />

& H. Wilden (eds) BUNDESENTSCHÄDIGUNGSGESETZE KOMMENTAR, Munich, C.H.Beck (1960) and the<br />

references provided there.<br />

6 BGHZ 52, 371 at 381.<br />

7 W. Tappert DIE WIEDERGUTMACHUNG VON STAATSUNRECHT DER SBZ / DDR DURCH DIE<br />

BUNDESREPUBLIK DEUTSCHLAND NACH DER WIEDERVEREINIGUNG, Berlin, Berlin-Verl. Spitz (1995) 19-71<br />

gives a detailed analysis of the attempts at Wiedergutmachung that were undertaken.

2004] Lost Information and Competing Interests<br />

3<br />

property, which had been lost as a consequence of persecution in the period between<br />

1933 and 1945, had been undertaken. 8 However, after reunification, it was<br />

not clear how the forcible dispossession or confiscation of property, situated in the<br />

former ‘East zone’, could be brought in line with the new legal order in a reunited<br />

<strong>German</strong>y. 9 <strong>The</strong> victims 10 or their relatives demanded the necessary relief from the<br />

two uniting <strong>German</strong> governments. 11<br />

<strong>The</strong> framework within which certain property, expropriated or confiscated in the<br />

territory that would become the <strong>German</strong> Democratic Republic, was to be returned<br />

to its original owners, was first set out in the Joint Declaration in respect of the<br />

Regulation of Unresolved Property Questions. 12 <strong>The</strong> Joint Declaration formed the<br />

political and legal basis for the regulation of property in a new, reunified <strong>German</strong>y.<br />

Its aim was to return expropriated property in the <strong>German</strong> Democratic Republic to<br />

its original owners or their heirs, 13 although several pragmatic considerations restricted<br />

the general intention of restitution. <strong>The</strong> Joint Declaration was incorporated<br />

14 into the Unification Treaty, 15 and thus obtained binding legal force. 16 It<br />

8 D. Visser & T. Roux Giving back the Country: South Africa's Restitution of Land Rights Act, 1994 in Context<br />

in R.W. Rwelamira & G. Werle (eds) CONFRONTING PAST INJUSTICES - APPROACHES TO AMNESTY,<br />

PUNISHMENT, REPARATION AND RESTITUTION IN SOUTH AFRICA AND GERMANY, Durban, Butterworths,<br />

(1996) at 99.<br />

9 O. Kimminich DIE EIGENTUMSGARANTIE IM PROZEß DER WIEDERVEREINIGUNG - ZUR BESTANDSKRAFT DER<br />

AGRARISCHEN BODENRECHTSORDNUNG DER DDR, Frankfurt am Main, Landwirtschaftl. Rentenbank,<br />

(1990) at 80.<br />

10 Who were mostly Jews who survived the holocaust, or their descendants, but also included relatives of<br />

the conspirators of 20 July (the day on which a failed assassination attempt on Hitler took place).<br />

11 G. Fieberg Legislation and Judicial Practice in <strong>German</strong>y: Landmarks and Central Issues in the Property Question<br />

in M.R. Rwelamira & G. Werle (eds) CONFRONTING PAST INJUSTICES - APPROACHES TO AMNESTY,<br />

PUNISHMENT, REPARATION AND RESTITUTION IN SOUTH AFRICA AND GERMANY, Durban, Butterworths,<br />

(1996) at 82.<br />

12 Gemeinsame Erklärung zur Regelung offener Vermögensfragen, 15 June 1990, BGBl. 1990 II at 1273.<br />

13 D.P. Kommers THE CONSTITUTIONAL JURISPRUDENCE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY 2 nd ed.,<br />

Durham, Duke University Press, (1997) at 256.<br />

14 Incorporated into the Unification Treaty as Exhibit III, the agreement covered seized businesses and<br />

real estate-nearly all the industrial and landed property in the <strong>German</strong> Democratic Republic.<br />

15 Art. 41(1) of Vertrag zwischen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik<br />

über die Herstellung der Einheit Deutschlands-Einigungsvertrag - 31 August 1990, BGBl. 1990 II at 889.<br />

16 G. Fieberg Legislation and Judicial Practice in <strong>German</strong>y: Landmarks and Central Issues in the Property Question<br />

in M.R. Rwelamira & G. Werle (eds) CONFRONTING PAST INJUSTICES - APPROACHES TO AMNESTY,

4 G ERMAN L AW J OURNAL [Vol. 05 No. 01<br />

forms part of the foundations of modern <strong>German</strong> law. 17 To clarify the general provisions<br />

of the Joint Declaration, the Unification Treaty provided for more detailed<br />

measures regulating property issues. For present purposes, mention must be made<br />

of the Gesetz zur Regelung offener Vermögensfragen (<strong>Law</strong> on the Regulation of Unsolved<br />

Property Questions or the "Property Act"), 18 which regulated the circumstances<br />

under which the principle of natural restitution 19 would apply. Other legislation,<br />

20 which provided additional conditions to regulate the principle of natural<br />

restitution, falls outside the scope of this discussion.<br />

Rückübertragungsansprüche (restitution claims) had to be registered at one of the 221<br />

local branches of the Amt zur Regulung offener Vermögensfragen (Open Property Office)<br />

21 in <strong>German</strong>y. <strong>The</strong>se local Property Offices are subject to one of six superior<br />

(provincial) Property Offices. 22 Once a restitution claim had been lodged, the per-<br />

PUNISHMENT, REPARATION AND RESTITUTION IN SOUTH AFRICA AND GERMANY, Durban, Butterworths,<br />

(1996) at 83.<br />

17 B. Diekmann DAS SYSTEM DER RÜCKERSTATTUNGSTATBESTÄNDE NACH DEM GESETZ ZUR REGELUNG<br />

OFFENER VERMÖGENSFRAGEN, Frankfurt am Main, Lang, (1992) at 43-55.<br />

18 Gesetz zur Regelung von offener Vermögensfragen, BGBl. 1990 II at 1159.<br />

19 <strong>The</strong> principle of natural restitution (Rückgabe vor Entschädigung) refers to the policy actually to return<br />

property to the original owners. Where restitution is not possible, compensation may be advanced in<br />

stead. <strong>The</strong> policy of natural restitution is laid down and simultaneously limited in articles 41(1) and (2)<br />

of the Unification Treaty. <strong>The</strong> chief mechanism for giving this principle practical implication, was the<br />

Property Act. Section 1 is the key provision. Subsections (1) to (7) enumerate the various categories of<br />

property which could be subject of restitution claims, while subsection (8) excludes restitution in a further<br />

number of categories. Restitution before compensation did not mean that rehabilitation in the economic<br />

sphere would necessarily be guided by present market values. It merely established the precedence of<br />

rehabilitation in kind over rehabilitation in money.<br />

20 E.g. the Act on Special Investments in the <strong>German</strong> Democratic Republic (Gesetz über besondere Investitionen in<br />

der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik, BGBl. 1990 II at 1157) - the "Investment Act" and its successors, the<br />

"Investment Acceleration Act" (Gesetz zur Beseitigung von Hemnissen bei der Privatisierung von Unternehmen<br />

und zur Förderung von Investitionen, BGBl 1991 I at 766) and the "Investment Priority Act" (Gesetz<br />

Über den Vorrang für Investitionen bei Rückübertragungsansprüchen nach dem Bermögensgesetz-<br />

Investitionsvorranggesetz-BGBl 1992 I at 1268) provided additional conditions to regulate the principle of<br />

natural restitution.<br />

21 Restitution claims had to be registered in the local Property Office of the district where the claimant (or<br />

the deceased in the case of a claim by the descendants) last lived, but could also be directed to the office<br />

in the district where the property in question was situated. <strong>The</strong> victims of persecution under nationalsocialism<br />

and foreign residents had to register their claims at the Federal Ministry of Justice in Bonn.<br />

22 C.E. Scollo-Lavizzari RESTITUTION OF LAND RIGHTS IN AN ADMINISTRATIVE LAW ENVIRONMENT - THE<br />

GERMAN AND SOUTH AFRICAN PRODEDURES COMPAREDLL M Research Dissertation, University of Cape<br />

Town, (1996) at 45.

2004] Lost Information and Competing Interests<br />

5<br />

son with the power of disposition over the property - usually the Treuhand or another<br />

state or local authority - could not dispose of the land, 23 except in very limited<br />

circumstances. 24 <strong>The</strong> deadline for lodging restitution claims was set at 31 December<br />

1992. 25 Property not claimed by that date would belong to the person with de facto<br />

power of disposal over it. 26 Over 1.2 million applications were lodged, the majority<br />

concerning landownership and affecting over one-third of the land area of the former<br />

<strong>German</strong> Democratic Republic. 27<br />

After a restitution claim had been lodged, the relevant property office had to analyze<br />

the substance and feasibility of the claim. In some areas, like the suburbs of<br />

Berlin and central areas of cities, multiple claims seeking recovery of the same<br />

pieces of land to different "prior" owners were sometimes encountered. 28 It was up<br />

to the federal, provincial and local property offices to trace the original owners of<br />

such property with proper title to it. Once a claim had been sufficiently clarified,<br />

the office would make a Vorbescheid (provisional decision), either to reject or uphold<br />

the claim, or find that the applicant is only entitled to compensation, and not restitution.<br />

29 Appeals against such a decision had to be directed to the superior Property<br />

Office in a specific area, where they would be decided upon by a committee established<br />

especially for this purpose. 30 If the claim for restitution was endorsed, an<br />

application could be brought to the local Land Registry for the entry of the correct<br />

23 Sec. 3(3)1 and 15(2) of the Property Act.<br />

24 E.g. where an investment priority decision or investment certificate had been granted. In such cases,<br />

the right to restitution was overridden. C.E. Scollo-Lavizzari RESTITUTION OF LAND RIGHTS IN AN<br />

ADMINISTRATIVE LAW ENVIRONMENT - THE GERMAN AND SOUTH AFRICAN PRODEDURES COMPARED, LL M<br />

Research Dissertation, University of Cape Town, (1996) at 45-50; M. Southern Restitution or Compensation:<br />

<strong>The</strong> Land Question in East <strong>German</strong>y 1993 INT. & COMP. L.Q 690 at 695.<br />

25 § 30a of the Property Act.<br />

26 Gesetz zur Änderung des Vermögensgesetzes und anderer Vorschriften (2. Vermögensrechtsänderungsgesetz)<br />

14 July 1992; 1992 BGBl. at 1257<br />

27 M. Southern Restitution or Compensation: <strong>The</strong> Land Question in East <strong>German</strong>y 1993 INT. & COMP. L.Q 690<br />

at 696, citing the FRANKFURTER ALLGEMEINE ZEITUNG of 24 Jan 1992; FINANCIAL TIMES of 25/26 Jan 1992.<br />

28 M. Southern Restitution or Compensation: <strong>The</strong> Land Question in East <strong>German</strong>y 1993 INT. & COMP. L.Q 690<br />

at 696.<br />

29 C.E. Scollo-Lavizzari RESTITUTION OF LAND RIGHTS IN AN ADMINISTRATIVE LAW ENVIRONMENT - THE<br />

GERMAN AND SOUTH AFRICAN PRODEDURES COMPARED,LL M Research Dissertation, University of Cape<br />

Town, (1996) at 50 ff.<br />

30 Ibid. 46 ff.

6 G ERMAN L AW J OURNAL [Vol. 05 No. 01<br />

particulars of the proprietor. 31 If a claim was rejected by the property office in the<br />

provisional decision, an appeal could be lodged first at the provincial and subsequently<br />

at the federal property office. 32 After exhausting internal appeals, the applicant<br />

could appeal to the Administrative Court. 33 It was expected that only a few of<br />

the numerous restitution claims would result in court proceedings, since most<br />

could be resolved through the administrative pre-trial phase of the process. 34 Every<br />

now and again, however, the judiciary is called upon to decide matters relating to<br />

the restitution procedure. 35 In particular, it has to deal with the difficult position<br />

ensuing from multiple claims in respect of a single land unit. From such decisions,<br />

the difficulties with the multi-layered demands placed by the restitution program<br />

on the <strong>German</strong> administrative and property law system becomes clear. <strong>The</strong> recent<br />

decision of the <strong>German</strong> Federal Administrative Court’s Seventh Senate, 36 which<br />

forms the subject of this discussion, is illustrative thereof.<br />

B. Background and Facts<br />

<strong>The</strong> case involved an erf in Berlin, which originally belonged to a person of the<br />

Jewish faith prior to World War II. 37 It was sold in 1936 to one R.Z., whose heirs<br />

were the applicants in the present case. Parts of the land were converted into socalled<br />

"Volkseigentum" in 1958, whilst the rest was expropriated roundabout 1984.<br />

31 G. Fieberg Legislation and Judicial Practice in <strong>German</strong>y: Landmarks and Central Issues in the Property Question<br />

in M.R. Rwelamira & G. Werle (eds) CONFRONTING PAST INJUSTICES - APPROACHES TO AMNESTY,<br />

PUNISHMENT, REPARATION AND RESTITUTION IN SOUTH AFRICA AND GERMANY, Durban, Butterworths,<br />

(1996) at 85.<br />

32 § 22-26 of the Property Act.<br />

33 M. Southern Restitution or Compensation: <strong>The</strong> Land Question in East <strong>German</strong>y 1993 INT. & COMP. L.Q 690<br />

at 695.<br />

34 M. Southern Restitution or Compensation: <strong>The</strong> Land Question in East <strong>German</strong>y 1993 INT. & COMP. L.Q 690<br />

at 696 provide interesting statistics as to the number of applications (said to have exceeded 1,1 million, of<br />

which 30 500 related to land and buildings, rather than businesses). In 1993, according to this source,<br />

only 8,5% of the land claims had been finalised, and it was speculated that the issue would take another<br />

30 years to resolve.<br />

35 G. Fieberg Legislation and Judicial Practice in <strong>German</strong>y: Landmarks and Central Issues in the Property Question<br />

in M.R. Rwelamira & G. Werle (eds) CONFRONTING PAST INJUSTICES - APPROACHES TO AMNESTY,<br />

PUNISHMENT, REPARATION AND RESTITUTION IN SOUTH AFRICA AND GERMANY, Durban, Butterworths,<br />

(1996) at 88.<br />

36 Decision of 23 October 2003, BverwG 7 C 62.02; VG 31 A 371.99.<br />

37 A more detailed version of the background to the case is contained in par I of the decision (note 36<br />

above).

2004] Lost Information and Competing Interests<br />

7<br />

In order to better understand the present case, it is necessary briefly to review those<br />

aspects of the confiscation and expropriation policy of the former <strong>German</strong> Democratic<br />

Republic which are relevant in the present discussion. Volkseigentum (People’s<br />

Property) refers to property, mostly of an industrial or agricultural nature and including<br />

land, buildings, installations, machinery, raw materials, industrial products,<br />

copyright and patents, which was expropriated for public purposes 38 after the<br />

establishment of the <strong>German</strong> Democratic Republic in 1949 and during its forty-year<br />

existence. 39 In most cases extremely low compensation, if any, was awarded. 40 <strong>The</strong><br />

ownership entitlements of “Peoples’ Property” were exercised by the socially<br />

owned firms of the state. 41 Enactment of expropriation legislation after the Soviet<br />

occupation zone became the <strong>German</strong> Democratic Republic in 1949 had as its main<br />

purpose the establishment of a socialist conception of ownership, 42 and therewith<br />

the transformation of individual ownership to so-called Volkseigentum. 43 On this<br />

basis countless expropriations and other infringements of property rights, in particular<br />

with regard to land, apartment ownership and means of production, took<br />

place. 44 <strong>The</strong>se confiscations and expropriations were undertaken in terms of regulations<br />

applying to all inhabitants of the <strong>German</strong> Democratic Republic, citizens as<br />

38 This included expropriation of land for the building of cities and development of belowstructure; for<br />

industrial settlements, energy management and for military purposes. D. Visser & T. Roux Giving back<br />

the Country: South Africa's Restitution of Land Rights Act, 1994 in Context in R.W. Rwelamira & G. Werle<br />

(eds) CONFRONTING PAST INJUSTICES - APPROACHES TO AMNESTY, PUNISHMENT, REPARATION AND<br />

RESTITUTION IN SOUTH AFRICA AND GERMANY, Durban, Butterworths, (1996) at 100.<br />

39 P.E. Quint THE IMPERFECT UNION - CONSTITUTIONAL STRUCTURES OF GERMAN UNIFICATION, Princeton,<br />

Princeton Univ. Press, (1997) at 124.<br />

40 Id.<br />

41 S. Pries DAS NEUBAUERNEIGENTUM IN DER EHEMALIGEN DDR, Frankfurt am Main, Lang, (1993) at 120-<br />

121.<br />

42 G. Fieberg Legislation and Judicial Practice in <strong>German</strong>y: Landmarks and Central Issues in the Property Question<br />

in M.R. Rwelamira & G. Werle (eds) CONFRONTING PAST INJUSTICES - APPROACHES TO AMNESTY,<br />

PUNISHMENT, REPARATION AND RESTITUTION IN SOUTH AFRICA AND GERMANY, Durban, Butterworths,<br />

(1996) at 82.<br />

43 D. Visser & T. Roux Giving back the Country: South Africa's Restitution of Land Rights Act, 1994 in Context<br />

in R.W. Rwelamira & G. Werle (eds) CONFRONTING PAST INJUSTICES - APPROACHES TO AMNESTY,<br />

PUNISHMENT, REPARATION AND RESTITUTION IN SOUTH AFRICA AND GERMANY, Durban, Butterworths,<br />

(1996) at 99.<br />

44 See in general M. Southern Restitution or Compensation: <strong>The</strong> Land Question in East <strong>German</strong>y 1993 INT. &<br />

COMP. L.Q 690 at 696 and the statistics provided by this source, mentioned in note 34 above.

8 G ERMAN L AW J OURNAL [Vol. 05 No. 01<br />

well as foreigners. 45 <strong>The</strong>y were not necessarily arbitrary, and not necessarily aimed<br />

at putting a particular group or person at a disadvantage, even if the compensation<br />

amounts offered (if any) were very low. Instead, they could be regarded as part of<br />

the socialist system of the <strong>German</strong> Democratic Republic. As a result, expropriation<br />

for the purpose of conversion to Volkseigentum only rarely gave rise to valid restitution<br />

claims. In the present case, the restitution claim only related to that part of the<br />

property that was expropriated in 1984.<br />

After enactment of the Property Act in 1990, R.Z. lodged a claim for restitution of<br />

the original erf at the "Open Property Office," which was responsible for handling<br />

all restitution claims. In 1992, before the cut-off date for the lodging of restitution<br />

claims, the Conference on Jewish Material Claims against <strong>German</strong>y Inc., which by<br />

law 46 was designated as the lawful heir of all Jewish patrimonial rights, likewise<br />

filed a general claim of restitution (or, alternatively compensation where the former<br />

was not possible) of all identifiable patrimonial rights envisaged by par 2 (1) and (2)<br />

of the Property Act. At this point the particular erf, which formed the subject matter<br />

of R.Z.’s claim, was not expressly affected by the Conference’s claim. It was only in<br />

1994, after thorough research, that information from the so-called Jewish Address<br />

Book came to light, indicating that the relevant erf was affected by the Conference’s<br />

general claim.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Open Property Office initially rejected the claim of the Conference, but later<br />

retracted its original decision, deciding in 1998 that the relevant land had to be<br />

transferred to the Conference. 47 As such, the Open Property Office dealt with the<br />

clashing proprietary interests to the land by arguing that R.Z. was only second in<br />

line as far as the claims for restitution were concerned. 48<br />

<strong>The</strong> applicant in the ensuing dispute was one of R.Z.’s heirs. His request that the<br />

land be retransferred to the heirs of R.Z. was granted by the Administrative Court<br />

in Berlin in 2002. This decision was based mainly on the argument that the so-called<br />

individualization of the Conference’s general claim constituted a new claim for<br />

restitution, which could not be entertained since it fell outside the legislative cut-off<br />

45 For an overview of the situation, see M. Southern Restitution or Compensation: <strong>The</strong> Land Question in East<br />

<strong>German</strong>y 1993 INT. & COMP. L.Q 690ff. and P.E. Quint THE IMPERFECT UNION - CONSTITUTIONAL<br />

STRUCTURES OF GERMAN UNIFICATION, Princeton, Princeton Univ. Press, (1997) at 124ff.<br />

46 § 2 (1) of the Property Act.<br />

47 See the consideration of this aspect in par I of the Federal Administrative Court’s decision (note 36<br />

above).<br />

48 Id.

2004] Lost Information and Competing Interests<br />

9<br />

date for lodging of restitution claims, which was 31 December 1992. 49 <strong>The</strong> Administrative<br />

Court in Berlin regarded the individualization of the claim to the relevant<br />

land in 1994 as a new and separate act, not related to the original general claim of<br />

the Jewish Conference. 50 Against this result, the Jewish Conference brought an appeal,<br />

the process that gave rise to the consideration of the case by the Federal Administrative<br />

Court.<br />

C. Decision of the Federal Administrative Court<br />

<strong>The</strong> Federal Administrative Court eventually found in favor of the Jewish Conference.<br />

51 It was found that, although the Administrative Court in Berlin correctly<br />

assumed that the restitution claim had at least to be individualized, it did not acknowledge<br />

that such individualization could be effected through reference to deeds<br />

and documents mentioned in the lodged claim. Since the Administrative Court in<br />

Berlin did not regard reference to such documents as sufficient to determine the<br />

subject of the claim, 52 it did not establish facts necessary to the decision in the present<br />

instance, relating to the requirements for the payment o compensation in § 1(6)<br />

of the Property Act. Accordingly, the Federal Administrative Court decided to refer<br />

the case to the Administrative court for renewed consideration.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Federal Administrative Court’s reasoning was based on the relevance of the<br />

1992 cut-off date in the context of the general claim that was lodged by the Jewish<br />

Conference. 53 <strong>The</strong> cut-off date, according to the Court, has the purpose of ensuring<br />

the speedy establishment of legal certainty, limiting the debilitating effects of the<br />

restitution program on dealings with property and promoting investment. 54 <strong>The</strong>se<br />

purposes are in the interest of the Federal Republic as a whole. 55 It was indicated<br />

that, although the minimum requirements concerning the content of a particular<br />

claim are not specified by the Property Act, the Federal Administrative Court has in<br />

49 <strong>The</strong> details of the decision of the Berlin Administrative Court of 27 September 2002, in as far as they<br />

are relevant to the present case, are contained in par I of the Federal Administrative Court’s decision.<br />

50 Id.<br />

51 See par II of the Federal Administrative Court’s decision (note 36 above).<br />

52 Id.<br />

53 See par II (1) of the decision (note 36 above).<br />

54 <strong>The</strong>se objectives are articulated by the Court in par II (1) (a) of the decision (note 36 above).<br />

55 <strong>The</strong> court quotes the decisions of 24 June 1999 – BVerwG 7 C 20.98 and BVerwGE 109, 169 at 172 as<br />

authority.

10 G ERMAN L AW J OURNAL<br />

[Vol. 05 No. 01<br />

previous decisions established some norm in this regard. Accordingly, the affected<br />

patrimonial interests need at least to be individually specifiable. 56<br />

<strong>The</strong> Court then tested the present case against this requirement, focusing on the<br />

legal status of the Jewish Conference as successor organization, and found that the<br />

purpose for which it was instituted will not be served if a strict interpretation of<br />

§ 30 (1) Sent. 1 and § 30a (1) Sent. 1 read with § 2 (1) Sent. 3 of the Property Act is<br />

preferred. 57 In particular, the Jewish Conference was acknowledged as the legal<br />

successor of numerous unknown Jewish right holders. 58 This quality had to be<br />

heeded when the requirement of specification of the restitution object was to be<br />

considered. 59 <strong>The</strong> Court particularly remarked that the situation of the Jewish Conference<br />

cannot be compared to that of other claimants, who, as a rule, could more<br />

readily determine the identities of their predecessors-in-title and the nature of the<br />

patrimonial interests affected. 60<br />

<strong>The</strong> Court acknowledged that the requirement of specification of a particular claim<br />

is purposeful and in line with the requirements of § 30 (1) Sent. 1 of the Property<br />

Act. 61 However, it was also mindful of the particular position of the Jewish Conference<br />

and its difficulty with strictly complying with the cut-off date whilst having to<br />

deal with difficulties of proving the dispossessions that occurred in respect of Jewish<br />

Property. 62 <strong>The</strong> Court considered the fact that the legislature was cognizant of<br />

these difficulties in respect of movable property, but not in respect of immovables. 63<br />

56 See par II (1) (a) of the decision (note 36 above), and the authority quoted: Decision of 5 Oct. 2000 –<br />

BVerwG 7 C 8.00 – Buchholz 428 § 30 VermG No. 21.<br />

57 In essence, a joint reading of these provisions of the Property Act indicates the prerequisites for restitution<br />

in terms of the Act, providing for the type of claims to be considered and the cut-off date for lodging<br />

of such claims.<br />

58 See par II (1) (a) of the decision (note 36 above).<br />

59 Id.<br />

60 See par II (2) (c) of the decision.<br />

61 See the court's reliance on BVerfGE 78, 20 at 24; BVerwG decision of 18 May 1995 – BVerwG 7 C 19.94<br />

– Buchholz 428 § 1 VermG No. 44 p. 117.<br />

62 See par II (2) (c) of the decision.<br />

63 See par II (1) (a) of the decision.

2004] Lost Information and Competing Interests<br />

11<br />

Mindful of the requirement that the object of restitution needs to be determinable in<br />

terms of the law, 64 the Court nevertheless specified that the restitution claim itself<br />

need not conclusively prove the exact content and situation of the restitution object.<br />

65 Instead, in order to stay in line with the cut-off date, the claim needs simply<br />

to contain specifications that would indicate particular patrimonial interests. 66 <strong>The</strong><br />

replacement of a particular interest by another at random must however be excluded.<br />

67 In other words, the restitution object needs to be specified in the lodged<br />

claim, but not individualized. Individualization can take place at a later point in<br />

time, thereby giving effect to the claim whilst simultaneously remaining within the<br />

boundaries set by the cut-off date. 68<br />

On the basis of this reasoning, the Court considered several aspects of the Jewish<br />

Conference’s claim. One part of the Conference’s general claim 69 indicated that it<br />

was particularly aimed at proprietary interests of Jews dispossessed or confiscated<br />

on the basis of discriminating regulations of the National-Socialist regime or related<br />

organizations. 70 It also specified the sources on the basis of which individualization<br />

of Jewish property could be established (e.g. state archives, documents kept in the<br />

respective municipal offices etc.). 71 <strong>The</strong> Federal Administrative Court found this<br />

description to be sufficiently detailed to warrant effectiveness of the timely general<br />

claim, when viewed in conjunction with the individualization that occurred in 1994<br />

after the Jewish address book with the relevant details of the property was consulted.<br />

72 It was apparent from the documents consulted by the Jewish Conference<br />

and presented during the course of the proceedings that the initial disposal of the<br />

64 § 2 (1) (3) of the Property Act.<br />

65 Par II (1) (b) of the decision (note 36 above).<br />

66 Id.<br />

67 See the court's reliance on the decision of 28 March 1996 – BVerwG 7 C 28.95 – BVerwGE 101, 39 at 43.<br />

68 Here the court relies on its previous decision of 24 June 1999 – BVerwG 7 C 20.98 – BVerwGE 109, 169<br />

at 172.<br />

69 <strong>The</strong> so-called "Anmeldung 3". <strong>The</strong> Conference's claim was structured in three parts, the first two of<br />

which did not pass the scrutiny of the court, the first because of the very general nature in which it was<br />

phrased, and the second because of the element of chance in respect of its assumption of Jewish property<br />

which was built into the claim. See par I and II (2) (a) and (b) of the decision (note 36 above).<br />

70 See par II (2) (c) of the decision (note 36 above).<br />

71 Id.<br />

72 Id.

12 G ERMAN L AW J OURNAL<br />

[Vol. 05 No. 01<br />

property by its Jewish owner to R.Z. amounted to a forced sale. 73 This information<br />

was not displayed in the general address book of registered immovable property,<br />

since it was not usual at the time of the original disposal to publicize Jewish land<br />

relations. 74 As a result, this particular piece of land never became the subject of an<br />

award under the Wiedergutmachung policy of the former West <strong>German</strong>y and the<br />

Allied forces.<br />

D. Referral for Reconsideration<br />

On the basis of the arguments set out above, the Federal Administrative Court decided<br />

to refer the case back to the Berlin Administrative Court for reconsideration,<br />

ordering the latter specifically to take into account the evidence emanating from<br />

deeds and documents that can be advanced by the Jewish Conference. 75 In this context<br />

specifically, the Court provides a broad basis upon which evidence may be<br />

lead, when indicating that not only the Jewish address book of Berlin, but also any<br />

other documents or deeds which are mentioned in the general claim, must be considered<br />

in determining the ownership of the property in dispute. 76<br />

<strong>The</strong> Federal Administrative Court acknowledged that the referral for reconsideration<br />

of this case to the Administrative Court in Berlin will presuppose an additional<br />

effort to be made on the part of the latter. 77 It would have to clarify the ownership<br />

issue that was previously not considered on account of the Berlin court’s stance as<br />

to the application of the cut-off date requirement. <strong>The</strong> Federal Administrative<br />

Court then placed responsibility for leading of evidence on the Jewish Conference,<br />

indicating that the process needs to be facilitated by the co-operation of the applicant.<br />

78 <strong>The</strong> Jewish Conference was accordingly obliged to provide all relevant and<br />

available information that would aid the Berlin court’s decision. 79 <strong>The</strong> Federal Administrative<br />

Court added that this task should not be too difficult, in view of the<br />

73 Id.<br />

74 Id.<br />

75 Par II (3) of the decision (note 36 above).<br />

76 Id.<br />

77 Id.<br />

78 Id.<br />

79 Id.

2004] Lost Information and Competing Interests<br />

13<br />

evidence already lead by the Jewish Conference as to the ownership of the disputed<br />

property. 80<br />

E. Concluding Remarks<br />

<strong>The</strong> decision of the Federal Administrative Court indicates some of the difficulties<br />

still experienced when dealing with the reparation arrangements negotiated in the<br />

wake of the <strong>German</strong> reunification endeavor. On the one hand, the courts and administrative<br />

structures created for this purpose have to grapple with balancing<br />

interests of a variety of stakeholders, some of whom have no direct relation to the<br />

original dispossessory actions. On the other hand, the case makes it clear that at<br />

least a part of the present <strong>German</strong> property system is still based on actions which<br />

took place prior to or during World War II, and which involved confiscation or<br />

dispossession of property as a result of the discriminatory policies of the time.<br />

Added hereto is the problem of the disparate systems of property that developed in<br />

the divided <strong>German</strong>y after the war. Although the present case did not deal explicitly<br />

with the latter, it certainly indicates the scope of the repercussions, had a fullscale<br />

integration of these systems been incorporated in the reparation initiative<br />

after 1990.<br />

Another issue appearing from the present case is the question of missing information<br />

in the process of awarding restitution of property. As has been indicated by the<br />

Federal Administrative Court, the task of the Jewish Conference depends upon the<br />

degree to which information about confiscated, expropriated or abandoned property<br />

of those that suffered under the regime of National Socialism still exist and is<br />

accessible. <strong>The</strong> success with which this organization can fulfill its representative<br />

function will, further, be related to the judiciary and administration’s willingness to<br />

acknowledge the peculiar situation of the Conference, and to accommodate it in<br />

interpreting the requirements for restitution set by the Property Act.<br />

80 Id.

PUBLIC LAW<br />

Compensation Claims for Human Rights Breaches Committed<br />

by <strong>German</strong> Armed Forces Abroad During the Second<br />

World War: Federal Court of Justice Hands Down<br />

Decision in the Distomo Case<br />

By Sabine Pittrof *<br />

A. Introduction<br />

In recent times, an increased awareness in public international law of the significance<br />

of human rights has given rise to the idea of direct access to compensation<br />

claims by individuals in the case of severe human rights breaches. 1 This development<br />

has led to a number of actions for compensation in various jurisdictions. 2 <strong>The</strong><br />

Bundesgerichtshof (BGH – Federal Court of Justice) recently joined the series of decisions<br />

from higher courts addressing compensation claims for human rights<br />

breaches, handing down its landmark decision on compensation claims by Greek<br />

citizens whose parents were killed in a massacre in Distomo during the Second<br />

World War. 3<br />

* Dr. Sabine Pittrof LL.B. (Univ. N.S.W.), Haarmann Hemmelrath & Partner, Rechtsanwälte,<br />

Wirtschaftsprüfer, Steuerberater; Neue Mainzer Str. 75, 60311 Frankfurt am Main, Sabine.Pittrof@haarmannhemmelrath.com<br />

1 See e.g. Steffen Wirth, Staatenimmunität für internationale Verbrechen – das zweite Pinochet-Urteil des House<br />

of Lords, Jura 2000, 70.<br />

2 See e.g. ECHR, Al-Adsani v. United Kingdom, Application no. 35763/97, Judgment of 21 November 2001,<br />

available at http://hudoc.echr.coe.int; Areopag, Prefecture of Voiotia v. Federal Republic of <strong>German</strong>y, Case<br />

No 11/2000, Judgment of 4 May 2000; cf. also Markus Rau’s review of the Al-Adsani - decision: After<br />

Pinochet: Foreign Sovereign Immunity in Respect of Serious Human Rights Violations – <strong>The</strong> Decision of the<br />

European Court of Human Rights in the Al-Adsani Case in 3 GERMAN L. J .6 (June 1, 2002)<br />

www.germanlawjournal.com. Another important example of this trend is the ever-increasing amount of<br />

litigation under the American Alien Tort Claims Act. <strong>The</strong> case involving Unocal Corporation and allegations<br />

of human rights violations in Myanmar has drawn world-wide attention. See, John Doe I v. Unocal<br />

Corp., 2002 WL 31063976 (9th Cir. 2002); John Doe I v. Unocal Corp., 2002 WL 31063976 (9th Cir. 2003)<br />

(rehearing en banc).<br />

3 BGH, decision of 26 June 2003, III ZR 245/98, published in NJW 2003, 3488 et seq.

16 G ERMAN L AW J OURNAL<br />

[Vol. 05 No. 01<br />

B. <strong>The</strong> Court’s Decision<br />

I. Facts<br />

<strong>The</strong> appellants – Greek nationals – brought an action against the Federal Republic<br />

of <strong>German</strong>y for damages resulting from a massacre committed by the <strong>German</strong><br />

army in the Greek village of Distomo during the <strong>German</strong> occupation of Greece in<br />

1944. 4 On 10 June 1944, the appellants’ parents were shot by an SS-unit integrated<br />

into the <strong>German</strong> armed forces. 5 <strong>The</strong> shooting, termed a “retribution measure,” 6<br />

followed an armed conflict with partisans and involved 300 innocent inhabitants of<br />

the village. 7 <strong>The</strong> village itself was razed. 8<br />

<strong>The</strong> appellants claimed damages on behalf of their parents, whose claims had transferred<br />

to them by way of succession, with respect to the destruction of the parental<br />

home and business and in their own right with respect to damages to their health<br />

and disadvantages in their professional training and prospects. 9 <strong>The</strong> case was<br />

brought on appeal from the Oberlandesgericht (Higher Regional Court) of Cologne,<br />

which had dismissed the action. 10<br />

In 1997, the District Court of Livadeia in Greece had already awarded damages for<br />

the Distomo-massacre to, inter alia, the appellants. 11 This decision was upheld by<br />

the Greek Areopag in a judgment of 4 May 2000. 12 However, execution of the decision<br />

against assets of the Federal Republic of <strong>German</strong>y located in Greece could not<br />

take place for lack of the necessary permission by the Greek government required<br />

4 BGH NJW 2003, 3488.<br />

5 Id.<br />

6 Id.<br />

7 Id.<br />

8 Id.<br />

9 Id.<br />

10Id.<br />

11 District Court of Livadeia, Prefecture of Voiotia v. Federal Republic of <strong>German</strong>y, Case No 137/1997, Judgment<br />

of 30 October 1997.<br />

12 Cf. supra note 1.

2004] FCC hands down decision in the Distomo Case<br />

17<br />

under local law. 13<br />

II. Findings<br />

<strong>The</strong> Federal Court of Justice concluded that the claim for damages was without<br />

merit and the decision of the Cologne Higher Regional Court was upheld. Understanding<br />

the basis for the Court’s judgment requires a detailed analysis of several<br />

issues on which the decision was based.<br />

1. Res Judicata, the Recognition of Foreign Judgments and State Immunity<br />

<strong>The</strong> first issue presented to the Court was the question whether a <strong>German</strong> court<br />

was able to deal with the claim in light of the fact that the same factual situation<br />

had already been assessed by a Greek court. 14 <strong>The</strong> Court resolved that it could because<br />

the principle of res judicata only prevented a <strong>German</strong> court from reviewing<br />

the decision (révision au fond) if the <strong>German</strong> courts were obligated to recognise the<br />

foreign decision. 15 However, neither the <strong>German</strong>-Greek Treaty on Mutual Recognition<br />

and Execution of Court Judgments, Settlements and Public Documents in Civil<br />

and Commercial Matters of 4 November 1961, 16 nor § 328 Zivilprozeßordnung<br />

(ZPO – <strong>German</strong> Civil Procedure Code) dealing with the recognition of foreign<br />

judgments, imposed an obligation on the <strong>German</strong> courts to recognise the Greek<br />

decision. 17 Both required the Greek court to have had jurisdiction. 18 But this prerequisite<br />

was not met because the principle of state immunity had been breached. 19<br />

According to the principle of sovereign immunity recognised in public international<br />

law, a sovereign state can claim immunity from another state’s jurisdiction as<br />

13 For a more detailed account of the procedural history in the Greek courts see Elisabeth Handl, Introductory<br />

Note to the <strong>German</strong> Federal Court of Justice’s Judgment in the Distomo Massacre Case, 42 ILM<br />

1027.<br />

14 BGH NJW 2003, pp. 3488-3489.<br />

15 Id.<br />

16 BGBl. II 1963, 109.<br />

17 BGH NJW 2003, pp.3488-3489; cf. §§ 328 I Nos. 1 and 4 ZPO and Art. 3 Nos. 1 and 3 <strong>German</strong>-Greek<br />

Treaty.<br />

18 <strong>The</strong> court initially also looked at the Brussels Convention on Jurisdiction and the Enforcement of Judgments<br />

in Civil and Commercial Matters of September 27, 1968, but decided that it was not applicable as compensation<br />

claims against a sovereign state for acts committed while exercising sovereign powers did not<br />

come under the definition of “civil and commercial matters” stipulated in the treaty.<br />

19 BGH NJW 2003, 3488.

18 G ERMAN L AW J OURNAL<br />

[Vol. 05 No. 01<br />

long as acta jure imperii are concerned. 20 Being an act of the <strong>German</strong> armed forces,<br />

albeit illegal in all respects, this was to be classified as an act of sovereign power to<br />

which the principle of sovereign immunity applied. 21 While there had been a<br />

movement to restrict the application of this principle and exclude its applicability<br />

whenever mandatory rules (ius cogens) of public international law, such as human<br />

rights, are breached, 22 according to the prevailing opinion, this had not become a<br />

rule of current public international law. 23 <strong>The</strong>refore the Greek court did not have<br />

jurisdiction to hear the case and, accordingly, the Greek decision was not to be recognised<br />

by the <strong>German</strong> courts. 24 This opened the door for the <strong>German</strong> courts to<br />

adjudicate the situation de nouveau. 25<br />

2. Role of the Federal Republic of <strong>German</strong>y as the Respondent<br />

<strong>The</strong> Federal Court of Justice went on to discuss, briefly, whether the compensation<br />

claim was an independent post-war liability of the Federal Republic of <strong>German</strong>y or<br />

whether this was a claim for which the Federal Republic was liable under the principles<br />

of state succession. 26 It concluded that the lower courts were correct in deciding<br />

that specific post-war compensation legislation passed by the Federal Republic<br />

of <strong>German</strong>y did not apply to this case. 27 <strong>The</strong>refore it treated the claim as a liability<br />

of the <strong>German</strong> Empire rather than an original claim against the Federal Republic of<br />

<strong>German</strong>y. 28<br />

3. Effects of the London Debt Agreement<br />

Having established that the claims were originally claims against the <strong>German</strong> Empire,<br />

the Court considered the influence of the London Debt Agreement of<br />

20 See e.g., Malcolm N. Shaw, International <strong>Law</strong> 494 (4th ed. 1997).<br />

21 BGH NJW 2003, 3488 at 3489.<br />

22 See e.g. Steffen Wirth’s article referred to in Footnote 1.<br />

23 BGH NJW 2003, 3488 at 3489; for further reading, a selection of scholarly commentary on this topic can<br />

be found in the Court’s decision at p. 3489.<br />

24 BGH NJW 2003, 3488.<br />

25 BGH, NJW 2003, 3488-3489.<br />

26 Ibid. pp. 3489-3490.<br />

27 Id. <strong>The</strong> controlling post-war compensation statute was the Bundesentschädigungsgesetz of September<br />

1953, BGBl. I 1387.<br />

28 BGH NJW 2003, 3488 at pp. 3489-3490.

2004] FCC hands down decision in the Distomo Case<br />

19<br />

27 February 1953 on the case. 29 <strong>The</strong> Agreement served as a moratorium on reparation<br />

claims against <strong>German</strong>y until a final peace agreement dealing with reparation<br />

claims was signed. 30 <strong>The</strong>refore, claims resulting from the Second World War could<br />

not be finally adjudicated, whether they sought to award damages or dismiss the<br />

claim. 31 However, the Court went on to state that the so-called “Two-Plus-<br />

Four”Treaty (Zwei-plus-Vier-Vertrag) of 12 September 1990, paving the way for the<br />

unification of <strong>German</strong>y, although not a conventional peace agreement, was to be<br />

seen as a final agreement with respect to <strong>German</strong>y which had rendered the London<br />

Debt Agreement obsolete. 32<br />

4. Legal Basis for the Claims in the <strong>Law</strong> of 1944<br />

In order to evaluate whether claims for damages existed against the <strong>German</strong> Empire<br />

for which the Federal Republic of <strong>German</strong>y was liable, the Court then looked<br />

at whether the law as it was in 1944 provided a basis for the appellants’ suit. 33 In<br />

doing so, the Court examined the issue of compensation for tort claims under public<br />

international law as well as the issue of state liability under domestic law, eventually<br />

holding that neither of them supported the appellants’ case. 34<br />

Regarding the first question, the Court emphasised that while public international<br />

law may be changing gradually, certainly in 1944, the principle that public international<br />

law did not award direct protection to individuals as opposed to states still<br />

29 BGH NJW 2003, 3488 at 3490. <strong>The</strong> treaty was published at BGBl. II 1953, 336.<br />

30 For more information on the Agreement see, for instance, Edda Henrike Dolzer, International Treaties<br />

After World War II, in NS-FORCED LABOR: REMEMBRANCE AND RESPONSIBILITY 157 (Peer Zumbansen ed.,<br />

Nomos 2002); Libby Adler and Peer Zumbansen, <strong>The</strong> Forgetfulness of Noblesse: A Critique of the <strong>German</strong><br />

Foundation <strong>Law</strong> Compensating Slave and Forced Laborers of the Third Reich, in: 39 Harv. J. Leg. 1<br />

(2002), (reprinted also in: NS-Forced Labor: Remembrance and Responsibility 333 (Peer Zumbansen ed.,<br />

Nomos 2002).<br />

31 Art. 5 II London Debt Agreement; cf. also BGH NJW 1955, 631; NJW 1955, 1437; NJW 1973, 1549 at<br />

1552.<br />

32 BGH NJW 2003, 3488 at 3490. <strong>The</strong> Two-Plus-Four Treaty can be found at BGBl. II 1990, 1318. For further<br />

reading, a selection of scholarly commentary on this topic can be found in the Court’s decision at<br />

3490; see also, Dozer, supra note 30; Adler and Zumbansen, supra note 30.<br />

33 According to the Court, the legal basis for this is to be found in Art. 135a I No 1 Grundgesetz (GG-<br />

<strong>German</strong> Basic <strong>Law</strong>); cf. Bundesverfassungsgericht (Federal Constitutional Court) BVerfGE 15,126 at 145.<br />

Evidently, traces of Nazi - ideology to be found in the law of the time were not to be taken into account.<br />

BGH NJW 2003, 3488 at 3491.<br />

34 BGH NJW 2003, 3488 at 3491.

20 G ERMAN L AW J OURNAL<br />

[Vol. 05 No. 01<br />

held true, even in the case of a severe human rights infringement. 35 <strong>The</strong>refore only<br />

states or parties to a war could claim compensation. 36 <strong>The</strong> Convention Respecting<br />

the <strong>Law</strong>s and Customs of War on Land (Hague IV) of 18 October 1907 also sustained<br />

this interpretation in its Articles 2 and 3. 37<br />

With respect to the second issue, liability pursuant to domestic state liability provisions<br />

was also ruled out. 38 While the requirements under the respective provisions<br />

would have been met literally, it was the general understanding at the time of the<br />

massacre that acts of war committed on foreign soil were excluded from domestic<br />

state liability. 39<br />

C. Conclusion<br />

<strong>The</strong> decision is of interest for several reasons. Most obviously, it will likely act as a<br />

deterrent to other potential plaintiffs lodging further actions. While it would be<br />

desirable for the individuals who suffered directly or indirectly from this or other<br />

atrocities committed by <strong>German</strong> armed forces during the Second World War to be<br />

awarded damages, the effect of the Court’s approach may, in fact, guarantee more<br />

legal certainty by ensuring that issues of this kind are resolved in a public international<br />

law forum.<br />

Furthermore, the decision also deals with important issues of public international<br />

law, especially the principle of state immunity. While its reasoning is of course not<br />

binding in public international law, 40 it confirms the line taken by courts of other<br />

jurisdictions that the principle of state immunity has not been amended to exclude<br />

immunity from compensation claims for human rights abuses and crimes against<br />

humanity. Thus, it adds certainty as to the <strong>German</strong> position with respect to this<br />

issue. 41<br />

35 BGH NJW 2003, 3488 at 3491.<br />

36 Id.<br />

37 <strong>The</strong> Hague IV Convention can found at RGBl. 1910, 107 or Martens, NRG (troisième série), Vol.3, 461.<br />

38 BGH NJW 2003, 3488 at pp. 3491-3493.<br />

39 Id.<br />

40 Though it certainly can serve as evidence of customary international law.<br />

41 Reinhold Geimer, Völkerrrechtliche Staatenimmunität gegenüber Amtshaftungsansprüchen ausländischer<br />

Opfer von Kriegsexzessen, LMK 2003, 215 concludes that state immunity also serves as a guarantee for<br />

peace between the states (p. 216).

2004] FCC hands down decision in the Distomo Case<br />

21<br />

<strong>The</strong> decision also makes a clear statement with respect to the prerequisites for recognition<br />

of foreign judgments. It emphasises that recognition is only possible if<br />

jurisdictional requirements have been met. Especially when advising foreign clients,<br />

recognition and enforcement of foreign decisions in <strong>German</strong>y is very topical<br />

as Bettina Friedrich eloquently pointed out in her article “Federal Constitutional<br />

Court Grants Interim Legal Protection Against Service of a Writ of Punitive Damages<br />

Suit”. 42 <strong>The</strong>refore, practitioners will also welcome this decision.<br />

Finally, its elaboration on <strong>German</strong> state liability law also sheds more light on issues<br />

arising in this area, although the Court specifically left unanswered the question of<br />

whether its analysis is transferable to state liability law as it stands today. Admittedly,<br />

this was not an issue in this case, and it must be hoped that the Federal Republic<br />

of <strong>German</strong>y will not commit crimes against humanity. Nevertheless, the<br />

general question of whether and how far current domestic law must take into account<br />

new developments in public international law which have not yet been recognised<br />

as a general rule will be an interesting one to deal with in future cases.<br />

42 Bettina Friedrich, Federal Constitutional Court Grants Interim Legal Protection Against Service of a Writ of<br />

Punitive Damages Suit, 4 GERMAN L. J. 12, § 5 (December 1, 2003) www.germanlawjournal.com

PRIVATE LAW<br />

<strong>The</strong> Defence of “Change of Position” in English and<br />

<strong>German</strong> <strong>Law</strong> of Unjust Enrichment<br />

By Florian Mächtel *<br />

A. Introduction<br />

In its § 142(1) the American Restatement of the <strong>Law</strong> of Restitution 1 provides that “[t]he<br />

right of a person to restitution from another because of a benefit received is terminated<br />

or diminished if, after the receipt of the benefit, circumstances have so changed<br />

that it would be inequitable to require the other to make full restitution.” <strong>The</strong><br />

notion that the recipient of an unjustified benefit must in principle return not more<br />

than the enrichment that has actually “survived” in his hands, is not only fundamental<br />

to the American law of restitution, but can also be found in English and<br />

<strong>German</strong> law.<br />

In the seminal, 18 th Century case of Moses v. Macferlan, decided by the House of<br />

Lords, the highest Court in the United Kingdom, Lord Mansfield held, that the<br />

defendant to a restitutionary claim “may defend himself by every thing which<br />

[shows] that the plaintiff, ex aequo et bono 2, is not entitled to the whole of his demand,<br />

or to any part of it.” 3 This can be interpreted as an early hint at the so-called<br />

defence of “change of position.” 4 In <strong>German</strong>y, a similar principle, the Wegfall der<br />

Bereicherung (literally “cessation of the enrichment” but used to indicate the<br />

“change of position” defence), is enshrined in § 818 III of the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch<br />

* LL.M. (University of Birmingham, United Kingdom); Student Assistant, Chair of Civil <strong>Law</strong> and Legal<br />

History (Prof. Dr. Diethelm Klippel), Faculty of <strong>Law</strong> and Economics, University of Bayreuth, 95440<br />

Bayreuth, <strong>German</strong>y.<br />

1 Scott, A.W. and Seavy, W.A., Restatement of the <strong>Law</strong> of Restitution, Quasi Contracts and Constructive<br />

Trusts (St. Paul: American <strong>Law</strong> Institute 1937).<br />

2 “According to what is right and good.”<br />

3 2 Burr. 1005, 1010 (1760).<br />

4 In the American terminology, “change of circumstances.”

24 G ERMAN L AW J OURNAL<br />

[Vol. 05 No. 01<br />

(BGB – Civil Code), 5 which provides, in short, that the obligation to make restitution<br />

is excluded to the extent that the recipient of the benefit is no longer enriched.<br />

This essay will make a comparison of the application of the defence in <strong>German</strong>y<br />

and England. As the first part of the paper (B.), a brief outline of the restitutionary<br />

concepts in both countries, will show, this is especially interesting given the fact<br />

that the young English law of restitution is still “under construction” whereas<br />

<strong>German</strong> courts have applied their law for more than 100 years. <strong>The</strong> following chapter<br />

(C.) will try to locate the “loss of enrichment defence” and assess its importance<br />

for enrichment law. In the subsequent parts flesh will be put on the defence’s bones<br />

by examining its general requirements (D.), the role of fault and knowledge (E.), the<br />

problems of anticipatory reliance (F.) and counter-restitution (G.).<br />

As a conclusion (H.) it will be submitted that <strong>German</strong> and English law make use of<br />

the defence of change of position in a relatively similar way. <strong>The</strong> longer experience<br />

of the <strong>German</strong> system can serve as a useful guide, in a positive and a negative<br />

sense. <strong>The</strong> article is intended to give an introductory overview on an important, if<br />

not the most important, issue in enrichment law in two of Europe’s major jurisdictions.<br />

It deals with basic questions only, but the reader familiar with the law of<br />

restitution and its development will not be surprised by such an approach for an<br />

introduction, since it is a branch of the law which has aptly been described as a<br />

“minefield;” 6 there is hardly a position which is not disputed.<br />

B. Outline of the <strong>Law</strong> of Restitution<br />

“[A]ny civilized system of law is bound to provide remedies for cases of what has<br />

been called unjust enrichment,” Lord Wright correctly observed in the Fibrosa case,<br />

decided in 1943 by the House of Lords. 7 <strong>The</strong> task of this preliminary chapter is to<br />

provide a short comparison of this essential branch of the law in England and <strong>German</strong>y<br />

in order to illustrate how both legal systems approach the law of unjust enrichment.<br />

5 Most relevant statutory provisions can be found in English translation at<br />

http://www.iuscomp.org/gla/index.html (<strong>German</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Archive). Translations in this article are based<br />

on that source. All references in this paper are made to the BGB if not otherwise indicated. Roman numerals<br />

represent a paragraph, Arabic numerals a sentence. ‘s.’ means sentence if a section is not divided<br />

into paragraphs.<br />

6 Meier, Mistaken Payments in Three-Party Situations: A <strong>German</strong> View of English <strong>Law</strong>, 58 C.L.J. 567 (1999).<br />

7 Fibrosa Spolka Akcyjna v. Fairbairn <strong>Law</strong>son Combe Barbour Ltd., A.C. 32, 61 (1943).

2004] <strong>The</strong> Defence of “Change of Position”<br />

25<br />

I. England<br />

In England questions of unjust enrichment form part of the law of restitution,<br />

which encompasses all remedies depriving the defendant of a gain, instead of<br />

awarding compensation for the claimant’s loss. 8 For centuries the English courts<br />

granted relief in cases concerned with the skimming off of the defendant’s gains on<br />

the basis of quasi-contractual remedies and implied contractual obligations (money<br />

had and received, money paid, quantum valebat 9 , quantum meruit 10 ). 11 Although this<br />

view was doubted in the 1940s, 12 questions of unjust enrichment remained “a peripheral<br />

matter in contract or tort;” 13 the latter, restitution in the context of a tort,<br />

became acknowledged with the doctrine of “waiving the tort.” 14 Gradually, however,<br />

the law of restitution emancipated itself. This process culminated in its recognition<br />

as a discrete body apart from contract and tort at the beginning of the 1990s<br />

with the groundbreaking judgements of the House of Lords in Lipkin Gorman v.<br />

Karpnale Ltd. 15 and Woolwich Equitable Building Society v. IRC. 16<br />

In order to succeed with a claim in unjust enrichment one must prove that the defendant<br />

obtained a benefit at the plaintiff’s expense, a benefit that is unjust for him<br />

to retain because of special circumstances 17 commonly referred to as “unjust fac-<br />

8 VIRGO, THE PRINCIPLES OF THE LAW OF RESTITUTION 3 (Clarendon Press 1999). See also, Zimmermann,<br />

Unjustified Enrichment: <strong>The</strong> Modern Civilian Approach, 15 O.J.L.S. 413 (1995).<br />

9 “As much as it was worth.” When there is a sale of goods without a specified price, the law implies a<br />

promise from the buyer to the seller that the former will pay the latter as much as the goods were worth.<br />

10 “As much as he has deserved.” When a person renders a service without a specified price, there is an<br />

implied promise from the employer to the worker that he will pay him for his services, as much as he<br />

may deserve or merit.<br />

11 ZWEIGERT & KÖTZ, AN INTRODUCTION TO COMPARATIVE LAW 551 (T. Weir trans., Oxford University<br />

Press 3rd ed. 1998); Gallo, Unjust Enrichment: A Comparative Analysis, 40 A.J.C.L. 431 (1992).<br />

12 United Australia Ltd. v. Barclays Bank Ltd., A.C. 1, 26 (1941). (Lord Atkin); Fibrosa Spolka Akcyjna v.<br />

Fairbairn <strong>Law</strong>son Combe Barbour Ltd., A.C. 32, 63 (1943). (Lord Wright).<br />

13 Dickson, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Law</strong> of Restitution in the Federal Republic of <strong>German</strong>y: A Comparison with English <strong>Law</strong>, 36<br />

I.C.L.Q. 752 (1987).<br />

14 See, Hambley v. Trott, 98 E.R. 1136 (1776). (Lord Mansfield); Martinek, Der Weg des Common <strong>Law</strong> zur<br />

allgemeinen Bereicherungsklage. Ein später Sieg des Pomponius?, 47 RabelsZ 289 (1983).<br />

15 2 A.C. 548 (1991).<br />

16 A.C. 70 (1993).<br />

17 GOFF & JONES, THE LAW OF RESTITUTION para. 1-016 (Sweet & Maxwell 6th ed. 2002); VIRGO, THE PRIN-<br />

CIPLES OF THE LAW OF RESTITUTION 9 (Clarendon Press 1999); Chen-Wishart, Unjust Factors and the Resti-

26 G ERMAN L AW J OURNAL<br />

[Vol. 05 No. 01<br />

tors.” As with all claims there are also specific defences available for the enriched<br />

party, such as change of position. It is a matter of dispute whether the unjust enrichment<br />

principle and the law of restitution simply quadrate each other 18 or not. 19<br />

<strong>The</strong> proponents of the latter theory argue that proprietary claims and restitution for<br />

wrongs stand separately beside claims in unjust enrichment. Yet this paper is not<br />

the right place to elaborate on this point, since the question is of no particular relevance<br />

for the topic. 20 At this instant we can therefore record the following: <strong>The</strong> English<br />

law of restitution as such is a relatively young branch of the law. It is characterized<br />

by the notion that every enrichment can be retained, as long as there is no recognised<br />

ground which renders it unjust.<br />

II. <strong>German</strong>y<br />

<strong>The</strong> concept of “restitution” as it is understood in England does not at all exist in<br />

<strong>German</strong>y. 21 After further scrutiny, however, one will find several provisions dealing<br />

with the restoration of an unjust enrichment. <strong>The</strong> two most striking legal institutions<br />

in this context are §§ 346 et seq. (termination of contract) and §§ 812 et seq.<br />

(unjustified enrichment) in the BGB. No <strong>German</strong> jurist ever had the idea to combine<br />

all these claims into one “law of restitution,” because of the fixed structure of <strong>German</strong><br />

law. That is why restitutionary remedies can be located in a contractual context,<br />

in the law of obligations imposed by virtue of the law (gesetzliche Schuldverhältnisse),<br />

the law of property, family and succession law and even in social security<br />

and insurance legislation as well as public law. Thus, the comparative lawyer<br />

sees himself confronted with problems in structuring his analysis; indeed, as Professor<br />

Birks observes, it “is not a subject in which it is easy to draw comparisons.” 22<br />

Restitutionary Response 20 O.J.L.S. 557 (2000); Dickson, Unjust Enrichment Claims: A Comparative Overview<br />

54 C.L.J. 105 (1995).<br />

18 Lipkin Gorman (A Firm) v. Karpnale Ltd., 2 A.C. 548, 578 (1991). (Lord Goff); GOFF & JONES, THE LAW<br />

OF RESTITUTION para. 1-001 (Sweet & Maxwell 6th ed. 2002); BIRKS, AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LAW OF<br />

RESTITUTION 17 (Clarendon Press 1985) (but see my next fn.); HEDLEY, A CRITICAL INTRODUCTION TO<br />

RESTITUTION 11 (Butterworths 2001).<br />

19 VIRGO, THE PRINCIPLES OF THE LAW OF RESTITUTION 6-17 (Clarendon Press 1999); BIRKS, “Misnomer” in<br />

Cornish et al. (eds.), RESTITUTION: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE – ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF GARETH JONES 1<br />

(Hart 1998); <strong>The</strong> idea of "quadration" stems from Birks in An Introduction to the <strong>Law</strong> of Restitution. BIRKS,<br />

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LAW OF RESTITUTION 17 (Clarendon Press 1985).<br />

20 Nevertheless, for the sake of simplicity "restitution" and "unjust enrichment" will be used synonymously<br />

in this paper.<br />

21 Cf., Dickson, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Law</strong> of Restitution in the Federal Republic of <strong>German</strong>y: A Comparison with English <strong>Law</strong>, 36<br />

I.C.L.Q. 760 (esp. fn. 42) (1987).<br />

22 Birks, At the Expense of the Claimant: Direct and Indirect Enrichment in English <strong>Law</strong>, OXFORD U. COM-<br />

PARATIVE LAW FORUM 1 http://ouclf.iuscomp.org, after n. 4 (2000).

2004] <strong>The</strong> Defence of “Change of Position”<br />

27<br />

Sections 812-822 BGB form the core of the fragmented <strong>German</strong> “law of restitution.”<br />

<strong>The</strong>se provisions are part of the law of obligations, but belong neither to the law of<br />

contract, since obligations created by them do not arise out of contract but by virtue<br />

of law, nor to the law of delict, which deals with questions of compensation for<br />

wrongs. Nevertheless, the systematic position of these norms between the codified<br />

law of contract (§§ 433 et seq.) and the law of delict and property (§§ 823 et seq.)<br />

indicates that there are connections to these branches of the law. 23 <strong>The</strong> most important<br />

basis for a claim in unjustified enrichment is § 812 I 1, which mirrors the Roman<br />

condictiones indebiti and sine causa, 24 and it is worth stating it in full: “A person<br />

who obtains something by performance by another person or in another way at the<br />

expense of this person without legal cause is bound to give it up to him.” This seems<br />

to mirror the English principle of unjust enrichment outlined above. <strong>German</strong> scholars,<br />

however, have built an intellectual edifice of considerable height around that<br />