GALILEO: Scene Breakdown - Dassia N. Posner

GALILEO: Scene Breakdown - Dassia N. Posner

GALILEO: Scene Breakdown - Dassia N. Posner

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>GALILEO</strong>: <strong>Scene</strong> <strong>Breakdown</strong><br />

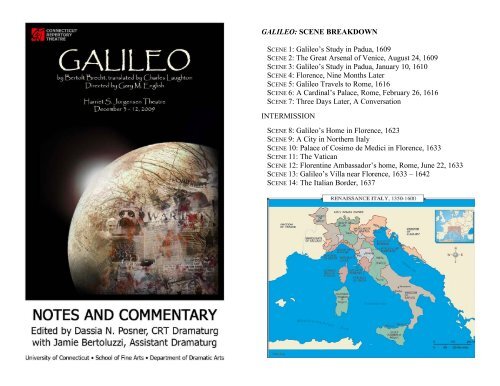

<strong>GALILEO</strong>: SCENE BREAKDOWN<br />

SCENE 1: Galileo’s Study in Padua, 1609<br />

SCENE 2: The Great Arsenal of Venice, August 24, 1609<br />

SCENE 3: Galileo’s Study in Padua, January 10, 1610<br />

SCENE 4: Florence, Nine Months Later<br />

SCENE 5: Galileo Travels to Rome, 1616<br />

SCENE 6: A Cardinal’s Palace, Rome, February 26, 1616<br />

SCENE 7: Three Days Later, A Conversation<br />

INTERMISSION<br />

SCENE 8: Galileo’s Home in Florence, 1623<br />

SCENE 9: A City in Northern Italy<br />

SCENE 10: Palace of Cosimo de Medici in Florence, 1633<br />

SCENE 11: The Vatican<br />

SCENE 12: Florentine Ambassador’s home, Rome, June 22, 1633<br />

SCENE 13: Galileo’s Villa near Florence, 1633 – 1642<br />

SCENE 14: The Italian Border, 1637

Ottavio Leoni, Portrait of Galileo Galilei, 1624<br />

PROLOGUE TO THE 1947 AMERICAN PRODUCTION OF <strong>GALILEO</strong><br />

Respected public of the way called Broad<br />

Tonight we invite you to step on board<br />

A world of curves and measurements, where you’ll descry<br />

The newborn physics in their infancy.<br />

Here you will see the life of the great Galileo Galilei<br />

The law of falling bodies versus the GRATIAS DEI<br />

Science’s fight versus the rulers, put on stage<br />

At the beginning of the modern age.<br />

Here you’ll see science in its blooming youth<br />

Also its first compromises with the truth.<br />

The Good, so far, has not been turned to goods<br />

But already there’s something nasty in the woods<br />

Which stops that truth from reaching the majority<br />

And won’t relieve, but aggravate their poverty.<br />

We think such sights are relevant today<br />

The Modern age is quick to pass away<br />

We hope you’ll lend a charitable ear<br />

To what we say, since otherwise we fear<br />

If you won’t learn from Galileo’s experience<br />

The Bomb will put in a personal appearance.<br />

(From Manheim and Willett, eds. Bertolt Brecht. Collected Plays. Vol. 5., p. 226)<br />

In Desmond Vesey’s translation of The Stargazer, Galileo tells Andrea<br />

Sarti the following “Mr. Keuner” story, later omitted in the Laughton<br />

edition:<br />

Into the home of the Cretan philosopher Keunos, who was beloved<br />

among the Cretans for his love of liberty, came one day, during the<br />

time of tyranny, a certain agent, who presented a pass that had been<br />

issued by those who ruled the city. It said that any home he set foot in<br />

belonged to him; likewise, any food he demanded; likewise, any man<br />

should serve him that he set eyes on. The agent sat down, demanded<br />

food, washed, lay down, and asked, with his face toward the wall,<br />

before he fell asleep: “Will you serve me?” Keunos covered him with a<br />

blanket, drove the flies away, watched over his sleep, and obeyed him<br />

for seven years just as on this day. But whatever he did for him, he<br />

certainly kept from doing one thing, and that was to utter a single word.<br />

When the seven years were up, and the agent had grown fat from much<br />

eating, sleeping, and commanding, the agent died. Keunos then<br />

wrapped him in the beat-up old blanket, dragged him out of the house,<br />

washed the bed, whitewashed the walls, took a deep breath and<br />

answered:<br />

“No.”<br />

Galileo’s drawings of his lunar observations

<strong>GALILEO</strong>: DIRECTOR’S NOTES<br />

Every day, images are created for our consumption from the<br />

mythology of culture, history and politics. Often we are more comfortable<br />

with these images than a more objective reality. Indeed, various power<br />

structures’ ability to self-perpetuate control over so many aspects of society<br />

depends on this dynamic: that many people prefer to believe an attractive<br />

lie than face an ugly truth. Despite the noble and important work produced<br />

by contemporary historians, many accept mythic versions of history and<br />

rely on iconic images of historical figures to teach us who they were and<br />

what they did. Ideology plays an important role in this process and fuels<br />

the perpetuating myth, however based in historical events, to manipulate<br />

our feelings in the present day. This process creates a disconnect between<br />

our experience and the truth of our history and in many cases excuses the<br />

circumstances we live under for the sake of this manufactured version of<br />

history.<br />

Bertolt Brecht believed that, as artists, we have a responsibility to<br />

change society for the better by telling the truth, and if artists have that<br />

responsibility, then certainly scientists share this same moral imperative.<br />

Brecht attempted to accomplish this by deconstructing mythic or iconic<br />

images of historical figures and by interrogating the behavior of those<br />

figures or historical events in general. To be sure, he does this by creating<br />

a fiction of his own, but the playwright and poet has the license to create<br />

fiction to discover truth, whereas the politician and the corporate power<br />

broker create fiction to disguise the truth. By deconstructing popular<br />

mythology, Brecht hopes to tear down our assumptions about our given<br />

circumstances in today’s world and, through interrogating our past,<br />

challenge those in power today about those given circumstances and our<br />

future.<br />

Nowhere is this better illustrated than in the current health care<br />

debate, where, certainly, the health insurance industry views its primary<br />

imperative as to protect and expand profits. To do this they are keen to<br />

perpetuate the “goodness” of capitalism and private enterprise, and the<br />

“badness” of government-run social programs, despite the success of many<br />

such programs in the United States and Europe. Without a popular iconic<br />

view of so-called “American Individualism” and a popular negative view of<br />

poverty as the endgame of insufficient self-reliance, these messages,<br />

including the recent comparison of a national health care program to the<br />

death camps of Nazi Germany, would be impossible to sell to the voting<br />

public.<br />

In 1938, Bertolt Brecht was particularly concerned about how to<br />

pursue and protect the truth in a tyrannical society, Nazi Germany in<br />

particular. By 1945, however, with the<br />

advent of the Atomic Bomb, he became<br />

equally concerned with the social and moral<br />

responsibility of all scientific activity as it<br />

might be manipulated by either a totalitarian<br />

regime, or within a liberal democracy.<br />

Brecht became fascinated with Galileo as one<br />

who had been lionized as the most important<br />

scientist of his time, which indeed he was,<br />

but who, upon closer inspection, might be<br />

challenged for his decision to recant under<br />

pressure by the Inquisition.<br />

My production of this play,<br />

translated by Charles Laughton and Bertolt<br />

Brecht, in part deals with the evolution in<br />

Brecht’s own view of Galileo, from the clever if sometimes dishonest rogue<br />

fending off the authorities, to the self-serving glutton who, consuming<br />

everything around him, helps the inquisition destroy intellectual progress,<br />

blasting us, metaphorically, back to the middle ages, in the way an<br />

unrestrained use of nuclear weapons would literally accomplish the same<br />

task. Brecht asks us a simple question; Why should Galileo get a pass from<br />

being courageous just because he was brilliant? Science, like all forms of<br />

public activity, requires valor. Now while some may complain that in order<br />

to do this Brecht had to invent the quality of cowardice in Galileo that is<br />

inherent in this play, devotees shouldn’t be too concerned. Brecht’s main<br />

purpose is to interrogate the historical icon in order for the rest of us to<br />

challenge other icons in our midst. Almost by reflected light, Brecht seems<br />

to view Galileo through the lens of Robert Oppenheimer, as he observed<br />

Oppenheimer’s own journey from patriotic scientist to a discarded threat to<br />

“national security.” On another level, Brecht saw in his investigation of<br />

Galileo an uncanny resemblance to his own situation under the scrutiny of<br />

HUAC, the House Committee on Un-American Activities.<br />

As only a dramatic fiction can produce, these images clash together<br />

as Brecht and Oppenheimer both ponder – sometimes separately,<br />

sometimes together as narrators – where we have come from and where we<br />

are going.<br />

-Gary M. English<br />

Photo: Two of Galileo’s first telescopes; Institute and Museum of the<br />

History of Science, Florence.

EVENTS THAT SHAPED <strong>GALILEO</strong>:<br />

by Jamie Bertoluzzi and <strong>Dassia</strong> N. <strong>Posner</strong><br />

_________________________________________________________________<br />

1609: Galileo first turns his telescope to the sky. The first telescope he creates is<br />

three-powered and by the end of the year he has created and presented to the<br />

Venetian Senate an eight-powered telescope. He observes the moon and,<br />

early in 1610, discovers the moons of Jupiter.<br />

1610: Galileo is appointed as Chief Mathematician of the University of Pisa and as<br />

Philosopher and Mathematician to the Grand Duke of Tuscany. This is a life<br />

position. Galileo moves to Florence.<br />

April 1611: Christopher Clavius and the Jesuit astronomers of the Collegium<br />

Romanum certify Galileo’s findings.<br />

February 1616: Pope Paul V orders Cardinal Bellarmine to warn Galileo not to<br />

support or defend the Copernican Theory. Galileo is also forbidden to<br />

discuss the theory.<br />

1620: Cardinal Maffeo Barberini’s writes a poem, “Adulatio Perniciosa<br />

(Dangerous Adulation),” in praise of Galileo.<br />

1623: Cardinal Barberini is elected Pope Urban VIII.<br />

1624: Pope Urban VIII gives Galileo permission to use the Copernican Theory in<br />

his writings as long as he treats it as a hypothesis.<br />

1630: Galileo finishes his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems,<br />

placing the scientific view of the new Pope in the mouth of a character<br />

named Simplicio.<br />

February 1632: After having passed the official censors, the Dialogue is printed.<br />

By September, distribution of the Dialogue is prohibited by the Pope.<br />

1633: Galileo is interrogated in April by the Inquisition. In June, Galileo<br />

acknowledges that he may have argued the Copernican Theory too strongly.<br />

He publicly recants his view that the Sun is the center of the universe. In<br />

December, he is allowed to return to his villa in Arcetri near Florence,<br />

where he is under house arrest for the remainder of his life.<br />

1636: Louis Elsevier, a Dutch publisher, visits Galileo and agrees to publish the<br />

Discourse on Two New Sciences.<br />

1638: Galileo’s Discourse on Two New Sciences is published in the Netherlands.<br />

1642: Galileo dies on January 8th at his villa in Arcetri.<br />

_________________________________________________________________<br />

1933: Hitler comes to power. Bertolt Brecht and his Jewish wife Helene Weigel<br />

leave Germany and flee to Denmark.<br />

1933-1945: The Holocaust<br />

1936-1938: Stalin conducts his “Show Trials,” forcing through torture public<br />

confessions of supposed attempts by leading figures to subvert Socialism.<br />

1938-1939: Brecht writes the first version of Galileo, The Earth Moves, translated<br />

into English in 1940 by Desmond Vesey as The Stargazer.<br />

1939: World War II begins. Neils Bohr announces the discovery of nuclear fission.<br />

1941: Pearl Harbor. As Hitler advances across Europe, Brecht flees to Santa<br />

Monica, California.<br />

1942-1945: Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, Scientific Director of the Manhattan<br />

Project in Los Alamos, New Mexico, begins developing an atomic bomb.<br />

The first bomb is tested on July 16, 1945 near Alamogordo, New Mexico.<br />

May 7, 1945: The Nazis surrender to the Allies.<br />

August 6, 1945: The atomic bomb is detonated over Hiroshima, Japan, and, a few<br />

days later, over Nagasaki. By the end of the year, there are c. 140,000<br />

bomb-related deaths in Japan. Japan surrenders the following month.<br />

1946: Oppenheimer receives the Presidential Medal of Merit for his work on the<br />

Manhattan Project and the atomic bomb.<br />

1945-1947: Brecht collaborates in California with actor Charles Laughton to create<br />

an English version of Galileo that responds to the tumultuous times. Galileo<br />

opens in Hollywood in July 1947.<br />

1947: Oppenheimer becomes the Director of the Institute for Advanced Study at<br />

Princeton University.<br />

October 30, 1947: Brecht appears before the House Committee on Un-American<br />

Activities and testifies that he is not a member of the Communist Party. He<br />

leaves the U.S. permanently the next day. Galileo runs briefly on Broadway<br />

in December.<br />

1949: Brecht and Weigel found their theatre, the Berliner Ensemble. The Soviet<br />

Union tests its first atomic bomb on August 29.<br />

1950: President Truman announces that he intends to pursue development of the<br />

hydrogen bomb. Oppenheimer is opposed to this. The Korean War begins.<br />

1952: The U.S. detonates the first hydrogen bomb in a test at Eniwetok in the<br />

Pacific.<br />

1953: Stalin dies. Oppenheimer calls for greater openness in the escalating atomic<br />

arms race. A few months later, Oppenheimer is charged with being a Soviet<br />

spy.<br />

April 12, 1954: The nearly month-long hearings against Oppenheimer begin.<br />

June 28, 1954: The Atomic Energy Commission votes to revoke Oppenheimer’s<br />

security clearance permanently, despite lack of evidence that the scientist<br />

shared any secrets.<br />

1957: A third version of The Life of Galileo premieres in both West and East<br />

Germany several months after Brecht’s death.<br />

_________________________________________________________________<br />

1992: Pope John Paul II states that the Catholic Church made a mistake in<br />

condemning Galileo’s teachings.<br />

2008: The Vatican announces plans to erect a statue of Galileo within the Vatican<br />

walls.<br />

2009: The International Year of Astronomy and the Year of Science.

BRECHT AND OPPENHEIMER:<br />

The FBI watched Brecht for much of his time in the U.S., recording nearly<br />

400 pages of documents on him. Brecht was subpoenaed to appear before<br />

the House Committee on Un-American Activities on October 30, 1947. The<br />

following is an excerpt from a statement he was not permitted to read:<br />

Being called before the Un-American Activities Committee… I<br />

feel free for the first time to say a word or two about American<br />

matters…. [T]he great American people would lose much and risk<br />

much if they allowed anyone to restrict the free competition of<br />

ideas in cultural fields, or to interfere with art, which must be free<br />

in order to be art. We live in a dangerous world…. [M]ankind is<br />

capable of becoming enormously wealthy but, as a whole, is still<br />

poverty-stricken. Great wars have been suffered; we are told<br />

greater ones are imminent. One of them might well wipe out<br />

mankind… Now do you not think that, in such a predicament,<br />

every new idea should be examined carefully and freely? Art can<br />

present such ideas clearly and even ennoble them. [Reproduced from<br />

Brecht before the Committee on Un-American Activities: A Historical Encounter.<br />

Presented by Eric Bentley/ Folkway Records, ©1967.]<br />

What Brecht actually said when asked directly if he was a member of the<br />

Communist Party:<br />

Mr. Chairman I have heard uh<br />

my colleagues uh, uhh, and<br />

they consider this question not<br />

as proper, but, I am a guest in<br />

this country and do not want to<br />

enter in any legal argument, so<br />

I will answer your question<br />

fully, as well I can. I was not a<br />

member, or am not a member,<br />

of any Communist party.<br />

Technically he did not lie; he was<br />

never a card-carrying member of the<br />

Communist Party of any country, but<br />

he deliberately underplayed the Marxist themes in many of his plays and<br />

poems.<br />

Photos: Brecht and his signature cigar before HUAC.<br />

Photo Life Magazine; J. Robert Oppenheimer.<br />

In 1942, Dr. J. Robert<br />

Oppenheimer became Scientific<br />

Director of the Manhattan Project<br />

in Los Alamos, New Mexico and<br />

was instructed to develop the<br />

world’s first atomic bomb. The<br />

FBI watched him closely,<br />

suspecting he had Communist<br />

sympathies. He and his team were<br />

successful in their quest, and in<br />

July 1945 detonated the first test<br />

bomb. Oppenheimer later said of<br />

this test in a television interview:<br />

We knew the world would<br />

not be the same. A few people<br />

laughed, a few people cried. Most<br />

people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture,<br />

the Bhagavad-Gita. Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he<br />

should do his duty, and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed<br />

form and says, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”<br />

The bomb’s role in World War II made Oppenheimer a national hero.<br />

Although he had moral trepidations about the bomb, in 1949, he still<br />

believed that science must ultimately be free:<br />

There must be no barriers for freedom of inquiry. There is no place<br />

for dogma in science. The scientist is free, and must be free to ask<br />

any question, to doubt any assertion, to seek for any evidence, to<br />

correct any errors.<br />

In 1950, however, Oppenheimer opposed Truman’s decision to pursue<br />

development of the hydrogen bomb and spoke out against the escalating<br />

arms race. His loyalty was questioned, the FBI documents on him<br />

surfaced, and he was subjected in 1954 to nearly a month of hearings<br />

resulting in the revocation of his security clearance, despite the<br />

committee’s inability to determine concrete wrongdoing. Brecht wrote<br />

about Oppenheimer in his journal in July 1954:<br />

he had moral objections to the hydrogen bomb and now he has<br />

been packed off to the wilderness. his document reads as if it was<br />

by a man who stands accused by a tribe of cannibals of having<br />

refused to go for the meat. and then claims by way of excuse that<br />

during the manhunt he was only collecting firewood for the<br />

cauldron. what darkness (Bertolt Brecht Journals. Trans. Hugh<br />

Rorrison; ed. John Willett. New York: Routledge, 1993, 458-459).

<strong>GALILEO</strong>: THE UNMAKING OF HEROES<br />

by <strong>Dassia</strong> N. <strong>Posner</strong>, CRT Dramaturg<br />

Galileo’s daughter never had a fiancé; she was a nun. Andrea Sarti<br />

did not smuggle the Discorsi out of Italy. Galileo’s contemporaries were<br />

not even especially concerned that humankind would suddenly be removed<br />

from the center of the universe. Brecht’s play is full of dates and citations<br />

from historical documents that give the air of accuracy, while much of its<br />

content is a selectively fictionalized account of Galileo’s life. Why, then, is<br />

this play called Galileo?<br />

While some historians and scientists remain outraged by Brecht’s<br />

seemingly insolent distortion of the facts of Galileo’s life, the playwright<br />

viewed the life of such a hero as rich fodder for the kind of altering we all<br />

engage in when we recount mythology. Would viewers be as upset if we<br />

told the story of the three little wolves and the big bad pig, or of Medea and<br />

Jason calmly resolving their issues in therapy? Treating the history of a<br />

universal hero as mythology made it possible for Brecht to comment on his<br />

own times. The Life of Galileo, for Brecht, thus had little to do with the life<br />

of Galileo. It had much more to do with the life and times of Bertolt<br />

Brecht.<br />

Even more enlightening is the manner in which Brecht consistently<br />

subverts the traditional notion of the hero in Galileo. His Galileo is a<br />

complex, conflicted individual who is both pragmatic and aware of his<br />

betrayal of the people whom science is supposed to benefit. This Galileo<br />

finds himself placed by Brecht at the center of an argument over the<br />

responsibility of the scientist not only to seek truth, but also to use that truth<br />

for the benefit of humanity. It is no accident that most of the people<br />

Galileo surrounds himself with in this version come from humble origins.<br />

This Galileo is not a feeble victim of those who would repress truth, but is<br />

much worse: he is one who knows the truth and still does not speak it.<br />

Galileo has been called the most Aristotelian of Brecht’s plays.<br />

Once again, however, Brecht uses the classical structure of tragedy<br />

specifically in order to subvert it. Galileo would seem to be a tragic hero,<br />

but beginning in the very first scene, there is nothing noble in his<br />

opportunism. The play has a reversal, but it takes place with Galileo<br />

offstage, while we see only Galileo’s followers waiting with agonizing<br />

hope. Even when Andrea Sarti comes to see Galileo at the end of the play,<br />

desperately seeking to forgive Galileo once he learns of his new book, the<br />

scientist refuses to allow Sarti to go out into the world with continued<br />

illusions that there was<br />

anything heroic in his<br />

recantation. According to<br />

Brecht, the fact that our<br />

heroes have flaws is not the<br />

problem; it is that we put<br />

them on a pedestal to begin<br />

with.<br />

Lastly, there are<br />

deliberate religious parallels<br />

between Galileo and his<br />

followers and Jesus and his<br />

disciples. In fact, the<br />

primary function of Virginia<br />

Galilei’s religious devotion<br />

is to play counterpoint to<br />

Andrea Sarti’s similar<br />

worship of Galileo.<br />

Nowhere is this more clear<br />

than in <strong>Scene</strong> Twelve, the<br />

recantation scene, during<br />

which Sarti’s scientific<br />

catechism is recited over<br />

Virginia’s Hail Marys. This<br />

scene also has unmistakable echoes of the three Marys going to the tomb of<br />

Christ, only to be informed by an angel that he has risen from the dead.<br />

Galileo’s three followers wait for a similar resurrection, hoping that Galileo<br />

will save science through his martyrdom, but Brecht’s Galileo is no such<br />

Messiah. The only voice akin to an angel’s is that of the town crier,<br />

proclaiming the text of Galileo’s recantation.<br />

This year marks the 400 th anniversary of the astronomical<br />

discoveries Galileo made with his telescope. It also marks the bicentennial<br />

of both Abraham Lincoln’s and Charles Darwin’s births and 150 years<br />

since the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. During this<br />

year, when we ponder the contributions to society of so many great heroes,<br />

it could be that debunking them gives us precisely the perspective we need<br />

in order to travel forward, regardless of how and when we have to travel<br />

with “the truth under our coat.”<br />

Photo: Frontispiece for Galileo’s Dialogo

THE LIFE OF <strong>GALILEO</strong><br />

by Friedeman Weidauer<br />

In a series of loosely<br />

connected scenes<br />

spanning the years<br />

1609-1642, Bertolt<br />

Brecht’s The Life of<br />

Galileo (Leben des<br />

Galilei) depicts the<br />

17 th -century<br />

astronomer at work,<br />

at home with family<br />

and friends, and also<br />

in conversation and<br />

confrontation with<br />

representatives of Italy’s ruling elite. Brecht completed his first version of<br />

the play, titled The Earth Moves/ Life of Galileo… in exile in Denmark in<br />

1939. In 1945-1946 he collaborated with the actor Charles Laughton<br />

(1899-1962) on an English-language version, Galileo. The final version,<br />

for his East Berlin theater company, the Berliner Ensemble, was completed<br />

in 1956 and is a German translation of the English-language version<br />

bearing the title Leben des Galilei. After the dropping of the first nuclear<br />

bomb, Brecht made changes to his initial version, placing greater emphasis<br />

on the central theme of the play. Historically, both feudalism and<br />

capitalism have not granted science the freedom to be practiced for the<br />

well-being of all members of society, since the respective governmental<br />

rulers, church leaders, and business interests have frequently dictated which<br />

projects could be pursued in order to further their own power or material<br />

gain. Advocating a science free of such constraints, Brecht’s play<br />

foreshadows a society in which science facilitates the liberation of all<br />

classes from material need.<br />

The play is chiefly about the role of science and teaching in future<br />

social formations. As we have seen in the course of the 20 th century,<br />

socialist societies have never been able to deal with the social leverage that<br />

scientists hold through their control of intellectual property. Hence these<br />

societies have to offer them positions of privilege to keep them from going<br />

elsewhere. The scientists, in turn, were always easily tempted by the riches<br />

society could offer them, even if it meant pursuing science harmful to<br />

humanity as a whole. While agricultural and industrial property can be<br />

socialized– by choice or by force– and transferred to the possession of the<br />

state, intellectual property, in contrast, typically cannot. In this play Brecht<br />

works to find a way out of this impasse. Science has to come up with a<br />

method that takes it out of the hands of the few and puts it into the hands of<br />

the masses. As we witness the maturation of the naïve Andrea Sarti, the<br />

lower-class boy who has become Galileo’s student and subsequent heir to<br />

his method of research and teaching, we also witness the emergence of a<br />

new type of scientist, one who enables the masses to advance the progress<br />

of science rather than excluding them from the process. This is one of the<br />

main lessons Sarti learns from his teacher Galileo.<br />

The other is Galileo’s method of doing research, which in Brecht’s<br />

view represents a universal method for all sciences, as well as for the arts. It<br />

is a way of looking at natural, social, and aesthetic processes as if for the<br />

first time, by adopting a point of view in which nothing seems “natural.”<br />

Galileo’s research and teaching method not only constitutes a new,<br />

socialized way of doing science, but also embodies Brecht’s own theory<br />

and practice of the theater, a theater committed to teaching the spectator<br />

how to analyze processes and discover the forces behind them.<br />

The play is also about how science continues to decenter the human<br />

being. Just as Galileo’s teachings took the planet inhabited by humans out<br />

of the center of the universe, so Charles Darwin (1809), Karl Marx (1818-<br />

1883), and Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) decentered what had previously<br />

been thought of as the autonomous, self-determined individual at the center<br />

of human actions. This decentering, Brecht thought, would also pave the<br />

way for the development of the human species into a truly social one, thus<br />

dissolving the contours of the bourgeois individual.<br />

Finally, one can speculate that the play is also about the Moscow<br />

trials (1936-1938) that were occurring as the first version of the play was<br />

taking place…. If Galileo’s fat in the face of the Inquisition did not remind<br />

Brecht of the dangers some of his own friends were facing in a Soviet<br />

Union dominated by the paranoid Joseph Stalin (187901953), then we are<br />

left to think that the view of things Brecht intended to teach others<br />

sometimes failed the playwright himself.<br />

Friedemann Weidauer is editor of The Brecht Yearbook, Associate Professor<br />

of German, and Chair, German Section at UConn. This piece was originally<br />

published in The Columbia Encyclopedia of Modern Drama. New York:<br />

Columbia University Press, 2007 and is reprinted by permission of the author.<br />

Photo: Bertolt Brecht and Charles Laughton

CAN BRECHT STILL ROCK OUR (POST MODERN) WORLD?<br />

by Andrew Periale<br />

Verfremdungseffekt: a long word for a fairly simple (though much<br />

misunderstood) concept. While translated as the “alienation effect,” this<br />

needs a big asterisk; “alienation” here is not the dark, existential malaise<br />

that sends one sprinting for the Prozac, rather it should engender the feeling<br />

of being “from somewhere else.” It’s like traveling in a foreign country for<br />

the first time. Yes, travel (and I mean real vagabonding, not those prepaid<br />

vacation packages) is often uncomfortable and always at least a little bit<br />

dangerous. But everything appears new and strange—every street sign,<br />

food vender, beggar, bus stop—and the effect this has on our senses is to<br />

make us feel astonished by a life we’d become inured to. We feel born<br />

again. And that (I believe) is what Brecht wanted—for audiences to feel<br />

that his theatre was something foreign and exciting, that they were<br />

“strangers in a strange land” and could no longer sit back in their plush<br />

seats and be lulled by a staged version of a life with which they had become<br />

all too familiar.<br />

Accomplishing this held different challenges for Brecht than it does<br />

for us. He had merely to violate the conventions of Naturalism using a<br />

medium that is inherently (and gloriously) unnatural. In Brecht’s theatre,<br />

the very act of exposing the theatre’s lighting instruments to public view<br />

was shocking; How do we shock a Post-Modern audience? WWBD!?<br />

Happily, there are still artists who grab us by the throat and turn our<br />

perceptions inside out. The techniques for making us feel like aliens in a<br />

new country continue to be reinvented, and the proof of Brecht’s greatness<br />

is not the “epic” or “alienating” hocus pocus he devised, but that we<br />

continue to use his scripts to throw new light on our contemporary lives.<br />

Galileo may be the best example—Brecht rewrote the script several times<br />

in response to changing conditions. At the time of his death, he was<br />

working on a third version of the play. Were he alive today he would<br />

perhaps be adapting the material to expose the dark underbelly of Financial<br />

Institutions “too big to fail.”<br />

How will Galileo grab us now? That is the art of this company<br />

tonight.<br />

Andrew Periale is a playwright, poet, puppeteer and polyglot. Last spring<br />

he worked as a dramaturg on Underground Railway Theatre’s production<br />

of Galileo in Cambridge, Massachusetts.<br />

EPILOGUE<br />

Five years before Galileo built his first telescope and turned it to the<br />

heavens, a new star appeared in the sky. This new star, or “supernova,”<br />

provoked tremendous controversy, as the heavens were thought to be<br />

immutable and only the earthly world changeable. The Collins English<br />

Dictionary defines a supernova as “A star that explodes catastrophically…<br />

becoming for a few days up to one hundred million times brighter than the<br />

sun. The expanding shell of debris … creates a nebula that radiates radio<br />

waves, X-rays, and light, for hundreds or thousands of years.” A<br />

photograph in the lobby exhibit by Robert Gendler, “Thor’s Helmet,”<br />

contains a star thought to be on the verge of going supernova.<br />

As we have seen, Brecht’s new era was provoked by explosions of<br />

a different sort; the atomic bomb “derives its destructive power from the<br />

sudden release of a large amount of energy by fission of heavy atomic<br />

nuclei, causing damage through heat, blast, and radioactivity” (OED). In an<br />

unused epilogue to Galileo, Brecht described it differently:<br />

Riding in the new railway coaches<br />

To the new ships in the waves<br />

Who is it that now approaches?<br />

Only slave-owners and slaves.<br />

Only slaves and slave-owners<br />

Leave the trains<br />

Taking the new aeroplanes<br />

Through the heaven’s age-old blueness.<br />

Till the latest one arrives<br />

Astronomic<br />

White, atomic<br />

Obliterating all our lives.<br />

(Reproduced from Manheim and Willett, eds. Bertolt Brecht. Collected Plays.<br />

Vol. 5., p. 226-7)