Learning About Books and Children

Learning About Books and Children

Learning About Books and Children

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The more direct narrative voice of the fi rst person<br />

is quite common today. In contemporary realism it is<br />

almost the norm. Judy Blume helped popularize this<br />

kind of storytelling with books like Are You There,<br />

God? It’s Me, Margaret <strong>and</strong> Blubber. Blume’s stories<br />

are not known for strong characterization, but they<br />

do reveal the author’s ability to recreate the everyday<br />

language of children.<br />

The advantage of using fi rst-person narrative is that<br />

it can make for easy reading. It attempts to invite its<br />

au dience by taking a stance that says, “Look—we<br />

speak the same language.” However, children’s perspectives<br />

on the world are limited by their lack of experience,<br />

just as their vocabulary is. This is an added<br />

challenge for an author writing in the fi rst person; for<br />

al though it might be easy to present the narrator’s<br />

thoughts <strong>and</strong> feelings in an appealing way, it will be<br />

more diffi cult to show that the narrator’s view might<br />

be narrow, misguided, or simply immature when seen<br />

from a broader perspective.<br />

At times authors counter the limitations of a single<br />

point of view by alternating the presentation of several<br />

views within the same story or changing points<br />

of view. Konigsburg’s multiple narratives in The View<br />

from Sat urday add great richness to the textual tapestry.<br />

Author Linda Sue Park provides an innovative<br />

twist on this technique in Project Mulberry, when she<br />

intersects the fi rst-person narrative of her main character,<br />

Julia Song, with a dialogue between herself as<br />

author <strong>and</strong> Julia as a product of her imagination.<br />

The author’s personal <strong>and</strong> cultural experience is refl<br />

ected in more subtle ways in every book’s point of<br />

view. An author of color has a unique opportunity to<br />

illuminate those nuances of culture that outsiders can<br />

never capture. To be sure, there are writers who create<br />

fi ne literature from sustained contact with a culture<br />

other than their own. But their points of view are no<br />

substitute for those of an author who has lived those<br />

cultural experiences from birth.<br />

Additional Considerations<br />

The books we think of as truly excellent have signifi -<br />

cant content <strong>and</strong>, if illustrated, fi ne illustrations. Their<br />

total design, from the front cover to the fi nal end paper,<br />

creates a unifi ed look that seems in character with<br />

the content <strong>and</strong> invites the reader to proceed. Today we<br />

have so many picture storybooks <strong>and</strong> so many beautifully<br />

illustrated books of poetry, nonfi ction, <strong>and</strong> other<br />

genres that any attempt to evaluate children’s literature<br />

should consider both the role of illustration <strong>and</strong> the<br />

format of the book. We will discuss these criteria in<br />

greater depth in the chapters in Part 2 of this book.<br />

The format of a book includes its size, shape, page<br />

design, illustrations, typography, paper quality, <strong>and</strong><br />

binding. Frequently, some small aspect of the format,<br />

such as the book jacket, will be an important factor in<br />

a child’s decision to read a story.<br />

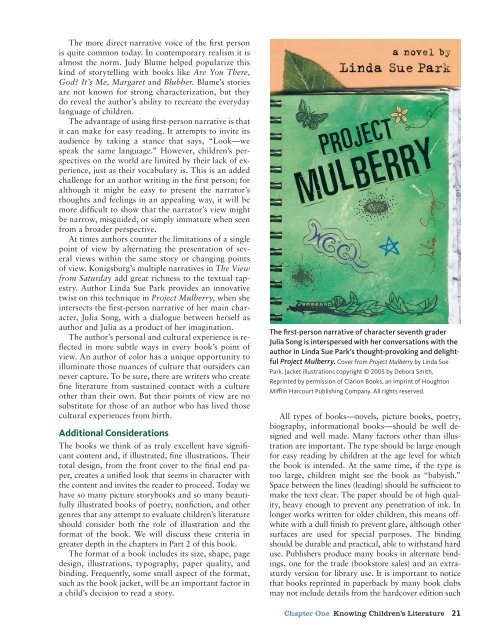

The fi rst-person narrative of character seventh grader<br />

Julia Song is interspersed with her conversations with the<br />

author in Linda Sue Park’s thought-provoking <strong>and</strong> delightful<br />

Project Mulberry. Cover from Project Mulberry by Linda Sue<br />

Park. Jacket illustrations copyright © 2005 by Debora Smith.<br />

Reprinted by permission of Clarion <strong>Books</strong>, an imprint of Houghton<br />

Miffl in Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.<br />

All types of books—novels, picture books, poetry,<br />

bi og raphy, informational books—should be well designed<br />

<strong>and</strong> well made. Many factors other than illustration<br />

are important. The type should be large enough<br />

for easy reading by children at the age level for which<br />

the book is intended. At the same time, if the type is<br />

too large, children might see the book as “babyish.”<br />

Space between the lines (leading) should be suffi cient to<br />

make the text clear. The paper should be of high quality,<br />

heavy enough to prevent any penetration of ink. In<br />

longer works written for older children, this means offwhite<br />

with a dull fi nish to prevent glare, although other<br />

surfaces are used for special purposes. The binding<br />

should be durable <strong>and</strong> practical, able to withst<strong>and</strong> hard<br />

use. Publishers produce many books in alternate bindings,<br />

one for the trade (bookstore sales) <strong>and</strong> an extrasturdy<br />

version for library use. It is important to notice<br />

that books reprinted in paperback by many book clubs<br />

may not include de tails from the hardcover edition such<br />

Chapter One Knowing <strong>Children</strong>’s Literature 21