Twenty-Five Years of Batson: An Introduction to ... - University of Iowa

Twenty-Five Years of Batson: An Introduction to ... - University of Iowa

Twenty-Five Years of Batson: An Introduction to ... - University of Iowa

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

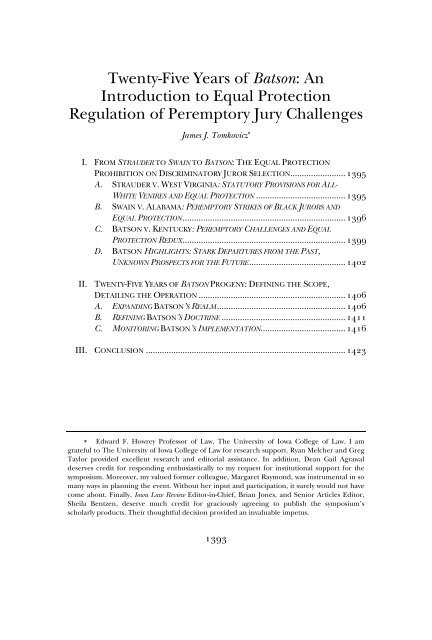

<strong>Twenty</strong>-<strong>Five</strong> <strong>Years</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong>: <strong>An</strong><br />

<strong>Introduction</strong> <strong>to</strong> Equal Protection<br />

Regulation <strong>of</strong> Peremp<strong>to</strong>ry Jury Challenges<br />

James J. Tomkovicz <br />

I. FROM STRAUDER TO SWAIN TO BATSON: THE EQUAL PROTECTION<br />

PROHIBITION ON DISCRIMINATORY JUROR SELECTION ........................ 1395<br />

A. STRAUDER V. WEST VIRGINIA: STATUTORY PROVISIONS FOR ALL-<br />

WHITE VENIRES AND EQUAL PROTECTION ....................................... 1395<br />

B. SWAIN V. ALABAMA: PEREMPTORY STRIKES OF BLACK JURORS AND<br />

EQUAL PROTECTION ....................................................................... 1396<br />

C. BATSON V. KENTUCKY: PEREMPTORY CHALLENGES AND EQUAL<br />

PROTECTION REDUX ....................................................................... 1399<br />

D. BATSON HIGHLIGHTS: STARK DEPARTURES FROM THE PAST,<br />

UNKNOWN PROSPECTS FOR THE FUTURE .......................................... 1402<br />

II. TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF BATSON PROGENY: DEFINING THE SCOPE,<br />

DETAILING THE OPERATION ................................................................ 1406<br />

A. EXPANDING BATSON’S REALM ........................................................ 1406<br />

B. REFINING BATSON’S DOCTRINE ...................................................... 1411<br />

C. MONITORING BATSON’S IMPLEMENTATION..................................... 1416<br />

III. CONCLUSION ....................................................................................... 1423<br />

Edward F. Howrey Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Law, The <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Iowa</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Law. I am<br />

grateful <strong>to</strong> The <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Iowa</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Law for research support. Ryan Melcher and Greg<br />

Taylor provided excellent research and edi<strong>to</strong>rial assistance. In addition, Dean Gail Agrawal<br />

deserves credit for responding enthusiastically <strong>to</strong> my request for institutional support for the<br />

symposium. Moreover, my valued former colleague, Margaret Raymond, was instrumental in so<br />

many ways in planning the event. Without her input and participation, it surely would not have<br />

come about. Finally, <strong>Iowa</strong> Law Review Edi<strong>to</strong>r-in-Chief, Brian Jones, and Senior Articles Edi<strong>to</strong>r,<br />

Sheila Bentzen, deserve much credit for graciously agreeing <strong>to</strong> publish the symposium’s<br />

scholarly products. Their thoughtful decision provided an invaluable impetus.<br />

1393

1394 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:1393<br />

On April 30, 2011, <strong>Batson</strong> v. Kentucky celebrated its twenty-fifth<br />

anniversary. Although not every member <strong>of</strong> the Supreme Court is convinced<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong>’s merits, 1 there is no movement afoot <strong>to</strong> overturn or dramatically<br />

modify it. A solid majority remains committed <strong>to</strong> the principles <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong> and<br />

its progeny and <strong>to</strong> the doctrinal framework that gives concrete content <strong>to</strong><br />

Equal Protection Clause regulation <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ry jury challenges. While the<br />

Court cannot always ensure faithful implementation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong>, in recent<br />

years the Justices have intervened when lower courts have been unfaithful <strong>to</strong><br />

the spirit <strong>of</strong> that landmark ruling. 2<br />

The Court has confronted <strong>Batson</strong> issues on several occasions since 1986.<br />

Some opinions have resolved significant questions about the breadth <strong>of</strong><br />

Fourteenth Amendment constraints upon peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges. 3 Others<br />

have involved efforts <strong>to</strong> prescribe the content <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong>’s doctrinal<br />

framework with greater precision. 4 Still others have revolved entirely around<br />

the correct application <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Batson</strong> doctrine <strong>to</strong> particular fact situations. 5<br />

The twenty-fifth anniversary <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong> is a fitting occasion for serious<br />

evaluation <strong>of</strong> both <strong>Batson</strong> and its descendants. This symposium’s goals are <strong>to</strong><br />

document the landmark’s current status, <strong>to</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r its vitality, <strong>to</strong> assess its<br />

impacts, and <strong>to</strong> reflect upon its future. The essays that follow ably<br />

accomplish these goals. Indeed, the authors have provided an impressive<br />

array <strong>of</strong> insights in<strong>to</strong> and evaluations <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong> and a number <strong>of</strong> provocative<br />

critiques <strong>of</strong> its significance and efficacy.<br />

This introduc<strong>to</strong>ry Essay serves as a primer. The primary objective is <strong>to</strong><br />

furnish a foundation for the analyses that follow. Part I describes the law<br />

prior <strong>to</strong> 1986 and documents how <strong>Batson</strong> dramatically altered the legal<br />

landscape, highlighting noteworthy facets <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Batson</strong> decision. Part II<br />

surveys and summarizes post-<strong>Batson</strong> developments. Part III concludes.<br />

1. See, e.g., Georgia v. McCollum, 505 U.S. 42, 60–62 (1992) (Thomas, J., concurring);<br />

Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S. 400, 425–26, 429–30 (1991) (Scalia, J., dissenting).<br />

2. See Snyder v. Louisiana, 552 U.S. 472 (2008); Miller-El v. Dretke, 545 U.S. 231 (2005);<br />

Miller-El v. Cockrell, 537 U.S. 322 (2003).<br />

3. See J.E.B. v. Alabama ex rel. T.B., 511 U.S. 127 (1994) (holding that gender-based<br />

strikes are unconstitutional); McCollum, 505 U.S. 42 (extending <strong>Batson</strong> doctrine <strong>to</strong> defense<br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ries); Powers, 499 U.S. 400 (concluding that defendant may raise equal protection<br />

challenge <strong>to</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ry strikes <strong>of</strong> jurors <strong>of</strong> a different race).<br />

4. See Johnson v. California, 545 U.S. 162 (2005); Purkett v. Elem, 514 U.S. 765 (1995)<br />

(per curiam); Hernandez v. New York, 500 U.S. 352 (1991).<br />

5. See Felkner v. Jackson, 131 S. Ct. 1305 (2011); Snyder, 552 U.S. 472; Miller-El v. Dretke,<br />

545 U.S. 231; Miller-El v. Cockrell, 537 U.S. 322.

2012] TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF BATSON 1395<br />

I. FROM STRAUDER TO SWAIN TO BATSON: THE EQUAL PROTECTION<br />

PROHIBITION ON DISCRIMINATORY JUROR SELECTION<br />

The Supreme Court found roots for <strong>Batson</strong> in a number <strong>of</strong> its prior<br />

decisions. The two most significant precedents were Strauder v. West Virginia 6<br />

and Swain v. Alabama. 7 This section summarizes those two opinions, explains<br />

<strong>Batson</strong>’s holding, and explores its premises.<br />

A. STRAUDER V. WEST VIRGINIA: STATUTORY PROVISIONS FOR ALL-WHITE VENIRES<br />

AND EQUAL PROTECTION<br />

Strauder v. West Virginia—decided more than a century before <strong>Batson</strong>—<br />

involved a state statute providing that only “white male persons” were<br />

eligible “<strong>to</strong> serve as jurors.” 8 Strauder, a black man indicted for murder by<br />

an all-white, all-male grand jury, moved “<strong>to</strong> quash the venire,” asserting that<br />

the preclusion <strong>of</strong> blacks from jury service “was unconstitutional.” 9 After the<br />

trial court overruled this motion, an all-male, all-white jury convicted<br />

Strauder, and the West Virginia Supreme Court affirmed. 10<br />

The question before the Supreme Court was whether, under “the<br />

Constitution and laws <strong>of</strong> the United States, every citizen . . . has a right <strong>to</strong> a<br />

trial <strong>of</strong> an indictment against him by a jury selected and impanelled without<br />

discrimination against his race or color, because <strong>of</strong> race or color.” 11 More<br />

specifically, the issue was “whether, in the composition or selection <strong>of</strong><br />

jurors . . . all persons <strong>of</strong> [a colored man’s] race or color may be excluded by<br />

law, solely because <strong>of</strong> their race or color, so that by no possibility can any<br />

colored man sit upon the jury.” 12 The Justices found guidance in the<br />

recently adopted Fourteenth Amendment command “that no State shall . . .<br />

deny <strong>to</strong> any person . . . the equal protection <strong>of</strong> the laws.” 13<br />

According <strong>to</strong> Strauder, the “purpose” <strong>of</strong> the Equal Protection Clause was<br />

<strong>to</strong> “secur[e] <strong>to</strong> a race recently emancipated . . . all the civil rights that the<br />

superior race enjoy.” 14 Its “spirit and meaning” was, quite simply,<br />

that the law in the States shall be the same for the black as for the<br />

white; that all persons, whether colored or white, shall stand equal<br />

before the laws <strong>of</strong> the States, and, in regard <strong>to</strong> the colored race . . .<br />

6. Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1879).<br />

7. Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965), overruled by <strong>Batson</strong> v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79<br />

(1985).<br />

8. Strauder, 100 U.S. at 305 (quoting 1873 W. Va. Acts 102).<br />

9. Id. at 304–05 (quoting Strauder’s motions <strong>to</strong> quash the venire).<br />

10. Id. at 305.<br />

11. Id.<br />

12. Id.<br />

13. Id. at 307. The Fourteenth Amendment was adopted in 1868, just eleven years before<br />

Strauder.<br />

14. Id. at 306.

1396 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:1393<br />

that no discrimination shall be made against them by law because<br />

<strong>of</strong> their color. 15<br />

The Justices had no doubt that West Virginia’s statute was<br />

discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry. 16 By restricting jury service <strong>to</strong> whites, West Virginia deprived<br />

potential black jurors <strong>of</strong> their constitutional entitlement. 17 Moreover, the<br />

statute unconstitutionally discriminated against black defendants who were put<br />

on trial. 18 In West Virginia, white men were entitled <strong>to</strong> trials by juries <strong>of</strong> their<br />

peers “selected without discrimination.” 19 Black men, who had no such<br />

entitlement, were denied the equal “protection <strong>of</strong> life and liberty against<br />

race or color prejudice.” 20 To subject a black man <strong>to</strong> trial “by a jury drawn<br />

from a panel from which the State has expressly excluded every man <strong>of</strong> his<br />

race, because <strong>of</strong> color alone” denied him “equal legal protection.” 21<br />

B. SWAIN V. ALABAMA: PEREMPTORY STRIKES OF BLACK JURORS AND EQUAL<br />

PROTECTION<br />

Eighty-five years later, Robert Swain, another black man, invoked<br />

Strauder’s “principle” in support <strong>of</strong> a quite different equal protection claim. 22<br />

Swain had been tried for and convicted <strong>of</strong> rape. 23 He alleged that the<br />

prosecu<strong>to</strong>r had violated the Fourteenth Amendment by using peremp<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

challenges <strong>to</strong> strike the six black members <strong>of</strong> the venire. 24 Alabama argued<br />

that its peremp<strong>to</strong>ry-strike system, which was a means <strong>of</strong> obtaining “fair and<br />

impartial” juries, “in and <strong>of</strong> itself, provide[d] justification for striking any<br />

15. Id. at 307.<br />

16. Id. at 308.<br />

17. Id. (explaining that the denial <strong>of</strong> the “right <strong>to</strong> participate in the administration <strong>of</strong> the<br />

law, as jurors, because <strong>of</strong> their color, . . . [was] practically a brand upon them, . . . an assertion<br />

<strong>of</strong> their inferiority, and a stimulant <strong>to</strong> that race prejudice which is an impediment <strong>to</strong><br />

securing . . . equal justice”).<br />

18. Id. at 309.<br />

19. Id.<br />

20. Id. According <strong>to</strong> the Court, the “framers <strong>of</strong> the [Fourteenth A]mendment” knew <strong>of</strong><br />

the prejudices that “<strong>of</strong>ten exist[ed] against particular classes in the community” and were<br />

motivated by an “apprehension that through [such] prejudice [black persons] might be<br />

denied . . . equal protection” <strong>of</strong> the laws and discriminated against. Id.<br />

21. Id.; see also id. at 310 (“[T]he statute <strong>of</strong> West Virginia, discriminating in the selection <strong>of</strong><br />

jurors, as it does, against negroes because <strong>of</strong> their color, amounts <strong>to</strong> a denial <strong>of</strong> the equal<br />

protection <strong>of</strong> the laws <strong>to</strong> a colored man when he is put upon trial for an alleged <strong>of</strong>fence against<br />

the State . . . .”).<br />

22. Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, 203 (1965), overruled by <strong>Batson</strong> v. Kentucky, 476 U.S.<br />

79 (1985).<br />

23. Id. at 203.<br />

24. Id. at 209–10. Peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges entitle a party <strong>to</strong> remove jurors without<br />

furnishing any reason. Each side in a criminal case has a prescribed number <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ries.

2012] TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF BATSON 1397<br />

group <strong>of</strong> otherwise qualified jurors in any given case, whether they be<br />

Negroes, Catholics, accountants or those with blue eyes.” 25<br />

The Court validated Alabama’s position. 26 The Court recounted the<br />

long his<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges in England and the United States, 27<br />

observing that their “function . . . is not only <strong>to</strong> eliminate extremes <strong>of</strong><br />

partiality on both sides, but <strong>to</strong> assure the parties that the jurors . . . will<br />

decide on the basis <strong>of</strong> the evidence . . . and not otherwise.” 28 Peremp<strong>to</strong>ries<br />

thereby promote “the appearance <strong>of</strong> justice.” 29 Their “very availability”<br />

enables lawyers <strong>to</strong> ask “probing questions” that might uncover “bias” and<br />

“facilitates the exercise <strong>of</strong> challenges for cause by removing the fear” that<br />

questions and for-cause challenges might antagonize jurors. 30<br />

The essence <strong>of</strong> a peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenge is an entitlement <strong>to</strong> exclude<br />

jurors without providing any “reason” and without any “inquiry” or “control”<br />

by the judge. 31 A party may reject jurors based on the jurors’ “real or<br />

imagined partiality,” their habits, associations, looks, or gestures or because<br />

<strong>of</strong> the party’s impressions, prejudices, or feelings. 32 Moreover, peremp<strong>to</strong>ries<br />

are “frequently exercised on grounds normally thought irrelevant <strong>to</strong> legal<br />

proceedings or <strong>of</strong>ficial action, namely, the race, religion, nationality, occupation<br />

or affiliations” <strong>of</strong> potential jurors. 33 In assessing the likelihood <strong>of</strong> partiality,<br />

parties do not always judge jurors “as individuals,” but rather, evaluate them<br />

“in light <strong>of</strong> the limited knowledge” possessed, “which may include their<br />

group affiliations, in the context <strong>of</strong> the case <strong>to</strong> be tried.” 34<br />

Swain asserts that the core “principle” <strong>of</strong> Strauder was that the<br />

purposeful denial <strong>to</strong> African Americans <strong>of</strong> the right <strong>to</strong> serve as jurors violates<br />

the Equal Protection Clause. 35 The government’s strikes <strong>of</strong> blacks in an<br />

individual case could not violate the Strauder principle because when<br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ries are exercised in an effort <strong>to</strong> secure “an impartial and qualified<br />

jury, Negro and white, Protestant and Catholic, are alike subject <strong>to</strong> being<br />

challenged without cause.” 36 Moreover, by examining the bases, the reasons,<br />

25. Id. at 211–12.<br />

26. Id. at 212.<br />

27. Id. at 212–19.<br />

28. Id. at 219.<br />

29. Id. (quoting In re Murchison, 349 U.S. 133, 136 (1955)) (internal quotation marks<br />

omitted).<br />

30. Id. at 219–20.<br />

31. Id. at 220.<br />

32. Id.<br />

33. Id. (emphasis added).<br />

34. Id. at 221 (emphasis added).<br />

35. Id. at 203–04.<br />

36. Id. at 221.

1398 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:1393<br />

or the sincerity <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges, courts would “radical[ly]” modify<br />

their character. 37 “[A] great many uses” would be forbidden. 38<br />

In sum, in Swain all nine Justices agreed that the positive contributions<br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges made <strong>to</strong> the fairness <strong>of</strong> jury trials precluded<br />

constitutional inquiry in<strong>to</strong> a prosecu<strong>to</strong>r’s reasons for exercising strikes. 39<br />

The presumption in any case was that a prosecu<strong>to</strong>r had used peremp<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

strikes “<strong>to</strong> obtain a fair and impartial jury,” and this presumption could not<br />

be “overcome” by “allegations” that black jurors had been excluded because<br />

<strong>of</strong> their race. 40 According <strong>to</strong> the Justices, <strong>to</strong> allow rebuttal <strong>of</strong> the<br />

presumption would have been “wholly at odds with the peremp<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

challenge system.” 41<br />

Swain also alleged that prosecu<strong>to</strong>rs had routinely and systematically<br />

used peremp<strong>to</strong>ry strikes <strong>to</strong> prevent black persons from serving as jurors,<br />

contending that no black person had ever served on a jury in that county. 42<br />

According <strong>to</strong> the majority, if Swain had demonstrated that prosecu<strong>to</strong>rs<br />

always struck all black jurors—preventing any blacks from ever serving on a<br />

jury in the jurisdiction—it might be “reasonable” <strong>to</strong> infer “that the<br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ry system [was] being used <strong>to</strong> deny [blacks] the same right and<br />

opportunity <strong>to</strong> participate in the administration <strong>of</strong> justice enjoyed by”<br />

whites. 43 Swain’s pro<strong>of</strong>, however, was insufficient because the record did not<br />

show with sufficient clarity “when, how <strong>of</strong>ten, and under what circumstances<br />

the prosecu<strong>to</strong>r alone ha[d] been responsible for striking” black jurors. 44 The<br />

mere showing that no black person had served on a jury was inadequate <strong>to</strong><br />

37. Id. at 221–22.<br />

38. Id. at 222.<br />

39. Id. The “persistence” and “extensive use” <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ries reflected our nation’s “long<br />

and widely held belief that” they are “a necessary part <strong>of</strong> trial by jury.” Id. at 219. Although the<br />

Constitution does not require states <strong>to</strong> afford them, in our nation peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges are<br />

“one <strong>of</strong> the most important . . . rights secured <strong>to</strong> the accused.” Id. (quoting Pointer v. United<br />

States, 151 U.S. 396, 408 (1894)) (internal quotation marks omitted).<br />

40. Id. at 222.<br />

41. Id. Consequently, the Court “insulate[d] from inquiry the removal <strong>of</strong> Negroes from a<br />

particular jury on the assumption that the prosecu<strong>to</strong>r [was] acting on acceptable considerations<br />

related <strong>to</strong> the case he is trying, the particular defendant involved and the particular crime<br />

charged.” Id. at 223.<br />

42. Id. at 222–23.<br />

43. Id. at 223–24. Remarkably, the Court did not declare that pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> such conduct would<br />

require that a prosecu<strong>to</strong>r explain strikes, much less that it would establish a violation <strong>of</strong> equal<br />

protection. Instead, Justice White observed that such a situation “may well require a different<br />

answer,” that in such a case “the Fourteenth Amendment claim takes on added significance,” that<br />

“it would appear that the purpose <strong>of</strong> the peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenge [was] being perverted,” that “the<br />

presumption protecting the prosecu<strong>to</strong>r may well be overcome,” and that pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> such facts<br />

“might support a reasonable inference” <strong>of</strong> exclusion for improper reasons and <strong>of</strong> abuse <strong>of</strong> the<br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenge <strong>to</strong> deny blacks an equal right “<strong>to</strong> participate in the administration <strong>of</strong><br />

justice.” Id. (emphases added).<br />

44. Id. at 224.

2012] TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF BATSON 1399<br />

support an “inference <strong>of</strong> systematic discrimination” by the State because this<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the jury selection process was not “wholly in the hands <strong>of</strong> state<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficers.” 45<br />

Thus, the Swain Court immunized a prosecu<strong>to</strong>r’s peremp<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

challenges in individual cases from equal protection scrutiny. The<br />

government’s consistent use <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges <strong>to</strong> keep black venire<br />

members from serving on juries might be unconstitutional for the same<br />

reasons that a whites-only statute was unconstitutional. 46 However, the pro<strong>of</strong><br />

demanded <strong>to</strong> establish a prima facie case <strong>of</strong> forbidden discrimination made<br />

it virtually impossible <strong>to</strong> prevail with an equal protection challenge <strong>to</strong><br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ries. 47<br />

C. BATSON V. KENTUCKY: PEREMPTORY CHALLENGES AND EQUAL PROTECTION<br />

REDUX<br />

<strong>Twenty</strong>-one years later, in <strong>Batson</strong> v. Kentucky, the Court reexamined the<br />

relationship between the prosecution’s peremp<strong>to</strong>ry removal <strong>of</strong> black jurors<br />

and the Equal Protection Clause. 48 The Court’s surprising opinion<br />

revolutionized that relationship.<br />

James <strong>Batson</strong>, a black man, was accused <strong>of</strong> burglary and receiving s<strong>to</strong>len<br />

goods. 49 Because the government struck all four black venire members, his<br />

jury was all white. 50 Defense counsel asked the court <strong>to</strong> discharge the jury,<br />

claiming that the removal <strong>of</strong> the black jurors had violated <strong>Batson</strong>’s Sixth<br />

Amendment right “<strong>to</strong> a jury drawn from a cross section <strong>of</strong> the community”<br />

and his Fourteenth Amendment right “<strong>to</strong> equal protection <strong>of</strong> the laws.” 51<br />

The trial judge rejected both contentions, and the jury convicted <strong>Batson</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

both crimes. 52 After the Kentucky Supreme Court also rejected <strong>Batson</strong>’s<br />

constitutional arguments, the Supreme Court granted certiorari. 53<br />

45. Id. at 227. Three Justices believed that when a defendant showed that no black person<br />

had ever served on a petit jury and that the prosecu<strong>to</strong>r had used peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges <strong>to</strong><br />

exclude blacks from his jury, he established “a reasonable inference that the State [was]<br />

involved” in unconstitutional discrimination. Id. at 241 (Goldberg, J., dissenting). Absent<br />

rebuttal, the defendant should prevail. Id. at 245–46. The majority’s demand for additional<br />

pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> state involvement was inconsistent with and undermined Strauder’s principles. Id. at<br />

231, 246.<br />

46. The Court was suggesting that it might not <strong>to</strong>lerate the circumvention <strong>of</strong> Strauder<br />

involved in having a neutral eligibility statute but a step in the actual selection process at which<br />

state ac<strong>to</strong>rs always blocked blacks from reaching petit juries.<br />

47. See Swain, 380 U.S. at 241–42, 246 (Goldberg, J., dissenting).<br />

48. <strong>Batson</strong> v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986).<br />

49. Id. at 82.<br />

50. Id. at 83.<br />

51. Id.<br />

52. Id.<br />

53. Id. at 84.

1400 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:1393<br />

Realizing that Swain precluded an equal protection argument based on<br />

the strikes at his trial, and “in an apparent effort <strong>to</strong> avoid inviting the Court<br />

directly <strong>to</strong> reconsider” that decision, the petitioner claimed only a<br />

deprivation <strong>of</strong> his Sixth and Fourteenth Amendment entitlement “<strong>to</strong> a jury<br />

drawn from a cross section <strong>of</strong> the community.” 54 The State sought <strong>to</strong> unmask<br />

<strong>Batson</strong>’s contention, maintaining that he was actually claiming an equal<br />

protection violation and that the Court could sustain that claim only by<br />

reconsidering Swain. 55 The Justices agreed that <strong>Batson</strong>’s challenge<br />

implicated “equal protection principles” and decided <strong>to</strong> revisit Swain, 56<br />

departing dramatically from its premises and conclusions.<br />

Writing for the majority, Justice Powell began with Strauder’s<br />

pronouncement that a state “denies a black defendant equal protection . . .<br />

when it puts him on trial before a jury from which members <strong>of</strong> his race have<br />

been purposely excluded.” 57 Racially discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry exclusion violates a<br />

defendant’s equal protection right by “den[ying] him the protection that<br />

a . . . jury is intended <strong>to</strong> secure.” 58 It deprives an accused <strong>of</strong> judgment by his<br />

peers, a vital safeguard “against the arbitrary exercise <strong>of</strong> power by prosecu<strong>to</strong>r<br />

or judge.” 59 Moreover, it enables <strong>of</strong>ficials <strong>to</strong> oppress minorities and denies<br />

defendants their right <strong>to</strong> protection against race prejudice. 60 The <strong>Batson</strong><br />

majority observed that discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry exclusion also violates the excluded<br />

jurors’ rights. 61 A juror’s competence depends on his “qualifications and<br />

ability impartially <strong>to</strong> consider evidence,” not on his race. 62 Furthermore,<br />

race-based exclusion harms “the entire community” by “undermin[ing]<br />

public confidence in the fairness <strong>of</strong> our system <strong>of</strong> justice.” 63<br />

Significantly, the Court declared that the “principles” forbidding racial<br />

discrimination in the selection <strong>of</strong> venires also extended <strong>to</strong> petit juries. 64 This<br />

extension subjected the prosecution’s peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges “<strong>to</strong> the<br />

commands” <strong>of</strong> equal protection. 65 The result was a Fourteenth Amendment<br />

54. Id. at 84 n.4.<br />

55. Id.<br />

56. Id. The Court “express[ed] no view on the merits <strong>of</strong> any <strong>of</strong> petitioner’s Sixth<br />

Amendment arguments.” Id.<br />

57. Id. at 85.<br />

58. Id. at 86.<br />

59. Id.<br />

60. Id. at 86 n.8.<br />

61. Id. at 87.<br />

62. Id. (citing Thiel v. S. Pac. Co., 328 U.S. 217, 223–24 (1946)).<br />

63. Id. at 87. According <strong>to</strong> the majority, race discrimination in the courtroom “is most<br />

pernicious because it is ‘a stimulant <strong>to</strong> that race prejudice which is an impediment <strong>to</strong><br />

securing . . . equal justice’” for blacks. Id. at 87–88 (quoting Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S.<br />

303, 308 (1879)).<br />

64. Id. at 88.<br />

65. Id. at 89.

2012] TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF BATSON 1401<br />

constraint on the principle that the government “ordinarily is entitled <strong>to</strong><br />

exercise . . . peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges ‘for any reason at all.’” 66 Put simply, “the<br />

Equal Protection Clause forbids . . . challenge[s <strong>to</strong>] potential jurors solely on<br />

account <strong>of</strong> their race or on the assumption that black jurors as a group will<br />

be unable impartially <strong>to</strong> consider the State’s case against a black<br />

defendant.” 67<br />

According <strong>to</strong> the Court, Swain recognized that the equal protection<br />

guarantee prevented the government from perverting peremp<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

challenges in<strong>to</strong> a <strong>to</strong>ol for denying blacks opportunities <strong>to</strong> serve. 68 The defect<br />

in that decision was procedural—it had “placed on defendants a crippling<br />

burden <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong>” and had effectively “immun[ized peremp<strong>to</strong>ries] from<br />

constitutional scrutiny. 69 Post-Swain decisions had established “that a<br />

defendant [could] make a prima facie showing <strong>of</strong> purposeful racial<br />

discrimination in selection <strong>of</strong> the venire by relying solely on the facts . . . in<br />

his case.” 70 Pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> a pattern <strong>of</strong> discrimination was unnecessary because an<br />

individual who suffers discrimination is denied equal protection whether or<br />

not the government discriminated against others. 71 The <strong>Batson</strong> majority<br />

found no reason not <strong>to</strong> extend these venire-selection principles <strong>to</strong> the petit<br />

jury selection process—and more specifically, <strong>to</strong> a prosecu<strong>to</strong>r’s use <strong>of</strong><br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ries. 72 Directly contravening Swain, the Court held “that a<br />

defendant may establish a prima facie case <strong>of</strong> purposeful discrimination in<br />

selection <strong>of</strong> the petit jury solely on evidence concerning the prosecu<strong>to</strong>r’s<br />

exercise <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges at [his] trial.” 73<br />

To establish a prima facie case, an accused “first must show that he is a<br />

member <strong>of</strong> a cognizable racial group . . . and that the prosecu<strong>to</strong>r has” used<br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ries <strong>to</strong> remove members <strong>of</strong> the accused’s race. 74 The defendant<br />

may then rely on the indisputable proposition that peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges<br />

enable discrimination by those inclined <strong>to</strong> discriminate. 75 “Finally, the<br />

defendant must show that these facts and any other relevant circumstances<br />

raise an inference” <strong>of</strong> juror exclusion “on account <strong>of</strong> their race.” 76 Judges<br />

66. Id. (quoting United States v. Robinson, 421 F. Supp. 467, 473 (D. Conn. 1976))<br />

(internal quotation marks omitted).<br />

67. Id.<br />

68. Id. at 91.<br />

69. Id. at 92–93.<br />

70. Id. at 95.<br />

71. Id. at 95–96.<br />

72. Id. at 96.<br />

73. Id.<br />

74. Id.<br />

75. Id.<br />

76. Id.

1402 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:1393<br />

must consider all pertinent circumstances <strong>to</strong> decide whether a defendant<br />

has raised such an inference. 77<br />

If the accused clears this hurdle, “the burden shifts <strong>to</strong> the State” <strong>to</strong><br />

furnish “a neutral explanation” for the allegedly discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry strikes. 78<br />

Although the “explanation need not rise <strong>to</strong> the level justifying . . . a<br />

challenge for cause,” 79 a prosecu<strong>to</strong>r cannot “merely” affirm his good faith or<br />

deny an intent <strong>to</strong> discriminate. 80 More important, the prosecution “may not<br />

rebut [a] . . . prima facie case <strong>of</strong> discrimination by stating merely that he<br />

challenged jurors <strong>of</strong> the defendant’s race on the assumption—or his<br />

intuitive judgment—that they would be partial <strong>to</strong> the defendant because <strong>of</strong><br />

their shared race.” 81 In fact, the state denies equal protection when it<br />

“strike[s] black veniremen on the assumption that they will be biased in a<br />

particular case simply because the defendant is black.” 82 If a prosecu<strong>to</strong>r<br />

<strong>of</strong>fers an adequate rebuttal explanation, a trial judge then has “the duty <strong>to</strong><br />

determine if the defendant has” carried the burden <strong>of</strong> “establish[ing]<br />

purposeful discrimination.” 83<br />

Because <strong>Batson</strong> “made a timely objection <strong>to</strong> the prosecu<strong>to</strong>r’s” use <strong>of</strong><br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges <strong>to</strong> “remov[e] . . . all black persons,” and the trial<br />

judge “flatly rejected the objection without” inquiry, the Court remanded<br />

the case for reconsideration in light <strong>of</strong> the prescribed standards. 84<br />

D. BATSON HIGHLIGHTS: STARK DEPARTURES FROM THE PAST, UNKNOWN<br />

PROSPECTS FOR THE FUTURE<br />

Before documenting the Court’s post-<strong>Batson</strong> journey, a few observations<br />

about Justice Powell’s landmark opinion are in order. The discussion that<br />

follows reflects upon the dramatic changes <strong>Batson</strong> effected and the<br />

uncertainties it generated.<br />

The <strong>Batson</strong> majority downplayed the magnitude <strong>of</strong> its alteration <strong>of</strong> the<br />

relationship between the Equal Protection Clause and peremp<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

77. Id. at 96–97.<br />

78. Id. at 97. Later, the majority suggested that a “neutral explanation related <strong>to</strong> the<br />

particular case <strong>to</strong> be tried” was necessary, id. at 98 (emphasis added), and indicated that rebuttal<br />

requires a “‘clear and reasonably specific’ explanation <strong>of</strong> [the prosecu<strong>to</strong>r’s] ‘legitimate<br />

reasons,’” id. at 98 n.20 (quoting Tex. Dep’t <strong>of</strong> Cmty. Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. 248, 258<br />

(1981)).<br />

79. Id. at 97.<br />

80. Id. at 98.<br />

81. Id. at 97.<br />

82. Id. Exclusion based on “such assumptions” would render the Fourteenth Amendment<br />

guarantee “meaningless.” Id. at 97–98. The Justices asserted that their decision would neither<br />

defeat the “fair trial values” peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges promote nor result in “serious<br />

administrative difficulties.” Id. at 98–99.<br />

83. Id. at 98.<br />

84. Id. at 100.

2012] TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF BATSON 1403<br />

challenges. Although Swain indicated that equal protection principles might<br />

bar discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry strikes that prevented any blacks from sitting on juries,<br />

the pro<strong>of</strong> demanded precluded any real constitutional regulation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenge system. <strong>Batson</strong>’s abandonment <strong>of</strong> that restriction—<br />

characterized as a relatively modest alteration <strong>of</strong> Swain’s burden <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong><br />

and based in part on general equal protection principles—was a dramatic,<br />

revolutionary step. 85 The allowance <strong>of</strong> equal protection claims based on the<br />

strikes in a single trial made frequent and substantial interference with the<br />

traditional operation <strong>of</strong> the peremp<strong>to</strong>ry system a realistic possibility.<br />

Whether or not claims <strong>of</strong> discrimination ultimately succeeded, it seemed<br />

likely that they would constrain prosecu<strong>to</strong>rs’ freedom <strong>to</strong> remove jurors and<br />

disrupt the accus<strong>to</strong>med processes <strong>of</strong> empanelling juries. The theoretical and<br />

practical ramifications <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong>’s procedural modification were considerably<br />

greater than the majority acknowledged. 86<br />

More noteworthy was the majority’s refusal <strong>to</strong> acknowledge that it was<br />

also foreswearing a substantive constitutional premise that no Justice found<br />

objectionable in Swain. 87 The Swain Court did not believe that removing a<br />

juror because <strong>of</strong> an assumption that her race would influence her<br />

deliberations was unconstitutional. 88 What the Fourteenth Amendment<br />

forbade was exclusion based on racial animus or a conclusion that members<br />

<strong>of</strong> a race were incompetent or unqualified. 89 The peremp<strong>to</strong>ry system<br />

permitted litigants <strong>to</strong> speculate and make inferences about how a person’s<br />

background and characteristics—including race—might impact mental<br />

processes and affect verdicts. 90 This use <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ries was not purposeful<br />

discrimination that <strong>of</strong>fended the Fourteenth Amendment’s spirit. There<br />

was, after all, no inequality when all individuals were subject <strong>to</strong> exclusion<br />

based on assumptions that their race could incline them against the<br />

government’s efforts <strong>to</strong> convict defendants <strong>of</strong> their race. 91<br />

In contrast, <strong>Batson</strong> held that peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges prompted by<br />

inferences that jurors’ perspectives and predilections could be affected by<br />

their racial identity deny equal protection. According <strong>to</strong> the majority, the<br />

Constitution forbids strikes based on the unsupported conclusion that race<br />

85. The magnitude <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong>’s change <strong>of</strong> course is illustrated by the fact that no Justice in<br />

Swain advocated constitutional scrutiny based on strikes in a single case.<br />

86. The Court rejected the contention that abandonment <strong>of</strong> the presumption <strong>of</strong><br />

legitimate use in individual cases jeopardized the functioning <strong>of</strong> the peremp<strong>to</strong>ry system. See<br />

<strong>Batson</strong>, 476 U.S. at 98–99.<br />

87. See id. at 134–37 (Rehnquist, J., dissenting).<br />

88. Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, 212, 220–21 (1965), overruled by <strong>Batson</strong>, 476 U.S. 79.<br />

89. Id. at 203, 224. The statute struck down in Strauder was objectionable because its<br />

exclusion <strong>of</strong> blacks from juries rested on this discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry premise. Id.<br />

90. Id. at 220–21.<br />

91. Id. at 221 (observing that all groups “are alike subject <strong>to</strong> being challenged without<br />

cause”).

1404 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:1393<br />

could impair impartiality. <strong>Batson</strong>, thus, rested on a very different, much<br />

more expansive view <strong>of</strong> unconstitutional discrimination than Swain. This<br />

change in the Court’s understanding <strong>of</strong> equal protection was a critical part<br />

<strong>of</strong> the foundation for altering the burden <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong> and authorizing claims<br />

based on strikes in a single case. If a prosecu<strong>to</strong>r strikes all black jurors in a<br />

case involving a black defendant, it could be because <strong>of</strong> hostility <strong>to</strong>ward<br />

blacks. On the other hand, the strikes could have been prompted by a fear<br />

that the jurors would favor the accused. 92 If the latter basis is constitutionally<br />

acceptable, then there is an insufficient likelihood that the strikes rested on<br />

an improper ground <strong>to</strong> justify the harm <strong>to</strong> the peremp<strong>to</strong>ry system caused by<br />

an inquiry. However, if both possible grounds for the strikes are invalid,<br />

then the likelihood that a prosecu<strong>to</strong>r who struck every black juror in a<br />

particular case was acting unconstitutionally is markedly higher—high<br />

enough <strong>to</strong> disrupt the peremp<strong>to</strong>ry system.<br />

The <strong>Batson</strong> majority minimized its procedural change and refused <strong>to</strong><br />

admit its substantive change. Both were dramatic departures from the prior<br />

interpretation <strong>of</strong> the relationship between the Fourteenth Amendment and<br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges. 93 It was clear in 1986 that <strong>Batson</strong> was gamechanging.<br />

Just how extensive its effects on constitutional rights and jury<br />

selection processes would be was unknown. <strong>Batson</strong> left open a number <strong>of</strong><br />

issues—the resolution <strong>of</strong> which would determine the nature and magnitude<br />

<strong>of</strong> its ultimate impact. 94<br />

92. Of course, each <strong>of</strong> the strikes could be for a reason not related <strong>to</strong> race.<br />

93. These differences between Swain and <strong>Batson</strong> seem even more remarkable in light <strong>of</strong><br />

the sources <strong>of</strong> the two opinions. If one were <strong>to</strong> excise all identifying information and ask<br />

anyone knowledgeable about the proclivities <strong>of</strong> the Warren and Burger Courts which opinion<br />

was the handiwork <strong>of</strong> which Court, <strong>Batson</strong> would be attributed <strong>to</strong> the Warren Court and Swain<br />

<strong>to</strong> the Burger Court. Earl Warren’s tenure was marked by his<strong>to</strong>rical efforts <strong>to</strong> eliminate racial<br />

inequality. See, e.g., Brown v. Bd. <strong>of</strong> Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954). Moreover, the Court<br />

announced expansive, <strong>of</strong>ten controversial, interpretations <strong>of</strong> Bill <strong>of</strong> Rights safeguards for those<br />

suspected or accused <strong>of</strong> crimes. See, e.g., Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966); Gideon v.<br />

Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963). During Warren Burger’s reign, the Justices were considerably<br />

less inclined <strong>to</strong> sustain race discrimination claims. See, e.g., Washing<strong>to</strong>n v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229<br />

(1976). In addition, the Court construed constitutional protections for suspects and defendants<br />

much more narrowly. See, e.g., Illinois v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213 (1983); Scott v. Illinois, 440 U.S.<br />

367 (1979).<br />

Nonetheless, the cautious, unprotective opinion in Swain is the Warren Court’s <strong>of</strong>fspring.<br />

The majority perceived no equal protection problem even though no black had ever served on<br />

a jury in the county where Swain was tried and was willing <strong>to</strong> declare only that pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

government responsibility for the absence <strong>of</strong> black jurors might establish a Fourteenth<br />

Amendment violation. It is counterintuitive, <strong>to</strong> say the least, that a seven-Justice Burger Court<br />

majority issued the pro-equality, pro-defendant <strong>Batson</strong> opinion. Moreover, the Court<br />

dramatically revised the Fourteenth Amendment–peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenge relationship in a case<br />

where the defendant did not even raise an equal protection claim. The Justices could have<br />

avoided the issue and decided only the Sixth Amendment fair-cross-section challenge raised by<br />

<strong>Batson</strong>.<br />

94. The next Part discusses the Court’s later answers <strong>to</strong> many <strong>of</strong> those questions.

2012] TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF BATSON 1405<br />

One overarching question was whether the Court’s incursion was the<br />

first step in a process leading <strong>to</strong> the abolition <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges. The<br />

contention that peremp<strong>to</strong>ries should be eliminated rests on the premise that<br />

conscious and unconscious race discrimination are realities that cannot be<br />

combated by mere regulation <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges and that the only<br />

way <strong>to</strong> effectively control unconstitutional use is abrogation. 95 The realities<br />

<strong>of</strong> discrimination and the fact that Swain’s approach was ineffectual were<br />

among the reasons for the <strong>Batson</strong> revolution, which many scholars have<br />

deemed woefully inadequate. 96 Nonetheless, it seems virtually certain that<br />

the Court will adhere <strong>to</strong> <strong>Batson</strong>’s more modest prescription and refuse <strong>to</strong><br />

perform the more radical surgery that some believe is essential. 97<br />

Other questions centered on the scope <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong>’s equal protection<br />

restrictions. Was <strong>Batson</strong> confined <strong>to</strong> race discrimination, as much <strong>of</strong> its<br />

language might suggest, 98 or might it also constrain other types <strong>of</strong><br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenge discrimination? 99 Whether the Constitution forbade<br />

strikes based on sex, religion, age, sexual orientation, or socio-economic<br />

status, for example, was unknown. 100<br />

<strong>An</strong>other question was whether a defendant could object <strong>to</strong> the removal<br />

<strong>of</strong> members <strong>of</strong> another race. <strong>Batson</strong>’s prima facie case required a showing<br />

that the prosecu<strong>to</strong>r removed jurors <strong>of</strong> the defendant’s race. 101 Moreover,<br />

<strong>Batson</strong> regulated peremp<strong>to</strong>ries exercised by the government. 102 The opinion<br />

contained no clear indications <strong>of</strong> whether there was any equal protection<br />

control over purposeful race discrimination by defendants.<br />

There were also “doctrinal” uncertainties in the wake <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong>. What<br />

was sufficient <strong>to</strong> establish an “inference” that would require the government<br />

<strong>to</strong> defend its peremp<strong>to</strong>ries? What showing by the government would suffice<br />

<strong>to</strong> rebut a prima facie case? The Court made clear that an explanation need<br />

not satisfy the “for cause” standard but did not specify the showing sufficient<br />

95. See <strong>Batson</strong> v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 103, 107–08 (1986) (Marshall, J., concurring); see<br />

also Morris B. H<strong>of</strong>fman, Peremp<strong>to</strong>ry Challenges Should Be Abolished: A Trial Judge’s Perspective, 64 U.<br />

CHI. L. REV. 809 (1997); Nancy S. Marder, Justice Stevens, the Peremp<strong>to</strong>ry Challenge, and the Jury, 74<br />

FORDHAM L. REV. 1683, 1715–17 (2006).<br />

96. See, e.g., Albert W. Alschuler, The Supreme Court and the Jury: Voir Dire, Peremp<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

Challenges, and the Review <strong>of</strong> Jury Verdicts, 56 U. CHI. L. REV. 153 (1989); Kenneth J. Melilli,<br />

<strong>Batson</strong> in Practice: What We Have Learned About <strong>Batson</strong> and Peremp<strong>to</strong>ry Challenges, 71 NOTRE DAME<br />

L. REV. 447, 505 (1996); Melynda J. Price, Performing Discretion or Performing Discrimination: Race,<br />

Ritual, and Peremp<strong>to</strong>ry Challenges in Capital Jury Selection, 15 MICH. J. RACE & L. 57 (2009).<br />

97. Among the Justices, there has been only isolated support for abolition. See Rice v.<br />

Collins, 546 U.S. 333, 342–44 (2006) (Breyer, J., concurring); Miller-El v. Dretke, 545 U.S.<br />

231, 273 (2005) (Breyer, J., concurring); <strong>Batson</strong>, 476 U.S. at 107–08 (Marshall, J., concurring).<br />

98. See <strong>Batson</strong>, 476 U.S. at 82, 86–88, 89, 93, 96.<br />

99. See id. at 123–24 (Burger, C.J., dissenting).<br />

100. See Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S. 400, 429–30 (1991) (Scalia, J., dissenting).<br />

101. <strong>Batson</strong>, 476 U.S. at 96.<br />

102. Id.

1406 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:1393<br />

<strong>to</strong> satisfy the Fourteenth Amendment. 103 Finally, the <strong>Batson</strong> majority<br />

declined <strong>to</strong> “instruct” judges on the practical question <strong>of</strong> “how best <strong>to</strong><br />

implement [its] holding.” 104 When a judge finds unconstitutional<br />

discrimination, she might “discharge the venire and select a new jury from a<br />

panel not previously associated with the case” or, alternatively, “disallow the<br />

discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry challenges and resume selection with the improperly<br />

challenged jurors reinstated on the venire.” 105 The Court refused <strong>to</strong> say<br />

whether either option was constitutionally required. 106<br />

II. TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF BATSON PROGENY: DEFINING THE SCOPE, DETAILING<br />

THE OPERATION<br />

In the two and a half decades since <strong>Batson</strong>, the Court has provided a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> insights in<strong>to</strong> the scope and operation <strong>of</strong> equal protection<br />

regulation <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges. Some decisions significantly<br />

broadened <strong>Batson</strong>’s purview, while others have substantially limited <strong>Batson</strong>’s<br />

impact. A few have moni<strong>to</strong>red fidelity <strong>to</strong> <strong>Batson</strong>, sending messages about<br />

extremes <strong>to</strong> be avoided by correcting outcomes that were either<br />

insufficiently or overly protective.<br />

A. EXPANDING BATSON’S REALM<br />

Just five years after <strong>Batson</strong>, the Court considered two significant issues<br />

about its ambit. In Powers v. Ohio, 107 the Court addressed whether a white<br />

defendant could obtain relief based on a claim that the prosecution<br />

discrimina<strong>to</strong>rily struck black jurors. 108 In Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co.,<br />

the Court considered whether parties in civil proceedings may remove jurors<br />

based on race. 109 The Court’s resolution <strong>of</strong> both issues broadened <strong>Batson</strong>’s<br />

reach and impact, setting a <strong>to</strong>ne and establishing premises for further<br />

expansion.<br />

103. The Court demanded a race-neutral reason, but also suggested that the explanation<br />

had <strong>to</strong> be “legitimate” and “related <strong>to</strong> the particular case.” Id. at 97–98, 98 n.20 (quoting Tex.<br />

Dep’t <strong>of</strong> Cmty. Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. 248, 258 (1981)).<br />

104. Id. at 99 n.24.<br />

105. Id.<br />

106. Each option had advantages and disadvantages. Striking a panel and starting anew is<br />

inefficient and costly. Moreover, prosecu<strong>to</strong>rs unhappy with the racial constituency <strong>of</strong> venires<br />

might deliberately violate <strong>Batson</strong> <strong>to</strong> secure new panels. On the other hand, reinstating struck<br />

jurors runs the risk that jurors who are upset by the effort <strong>to</strong> exclude them will retaliate.<br />

107. Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S. 400 (1991).<br />

108. A year earlier, in Holland v. Illinois, 493 U.S. 474 (1990), a bare majority had rejected<br />

a white defendant’s Sixth Amendment challenge <strong>to</strong> the State’s peremp<strong>to</strong>ry removal <strong>of</strong> black<br />

jurors, concluding that the fair-cross-section requirement did not bar race-based peremp<strong>to</strong>ries.<br />

Id. at 478. It was clear, however, that a majority would sustain an equal protection challenge in<br />

such circumstances. See id. at 488 (Kennedy, J., concurring); id. at 492 (Marshall, J., dissenting).<br />

109. Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co., 500 U.S. 614 (1991).

2012] TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF BATSON 1407<br />

In Powers, a white defendant on trial for murder and attempted murder<br />

objected <strong>to</strong> the government’s use <strong>of</strong> six <strong>of</strong> its nine peremp<strong>to</strong>ry strikes <strong>to</strong><br />

remove black venirepersons. 110 The trial court overruled the objections, and<br />

he was convicted. 111 On appeal, seven Supreme Court Justices concluded<br />

“that a criminal defendant may object <strong>to</strong> race-based exclusions <strong>of</strong> jurors<br />

effected through peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges whether or not the defendant and<br />

the excluded juror share the same race.” 112<br />

<strong>Batson</strong> held that a defendant established a prima facie case by showing<br />

that the prosecu<strong>to</strong>r removed members <strong>of</strong> his own race. Powers eliminated this<br />

constraint, concluding that a showing that strikes were used <strong>to</strong> remove<br />

members <strong>of</strong> any race sufficed. <strong>Batson</strong> had expressed concern not only with<br />

the impacts <strong>of</strong> discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry challenges on defendants but also with their<br />

effects on jurors and the community. 113 Strikes <strong>of</strong> jurors <strong>of</strong> a different race<br />

did not deprive the accused <strong>of</strong> equal protection, 114 but did infringe upon the<br />

jurors’ equal protection rights and the community’s interest in legitimate<br />

jury selection procedures. Consequently, the Court found it necessary <strong>to</strong><br />

accord criminal defendants third-party standing <strong>to</strong> raise jurors’ rights—and<br />

<strong>to</strong> grant them relief for violations <strong>of</strong> those rights. 115 In Edmonson, a black<br />

construction worker sued a concrete company, claiming injuries from an<br />

employee’s negligent truck operation. 116 When the company peremp<strong>to</strong>rily<br />

removed two black jurors, the plaintiff raised a <strong>Batson</strong> objection. 117 The<br />

lower courts refused <strong>to</strong> apply <strong>Batson</strong> <strong>to</strong> private civil litigants. 118<br />

Six Supreme Court Justices disagreed, concluding that <strong>Batson</strong>’s<br />

principles and safeguards extend <strong>to</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ries exercised by private<br />

parties in civil proceedings. 119 The majority piggybacked on the two central<br />

premises in Powers—that jurors struck on account <strong>of</strong> race suffer equal<br />

protection violations and that a party injured by unconstitutional strikes has<br />

110. Powers, 499 U.S. at 403.<br />

111. Id.<br />

112. Id. at 402. Justice Scalia objected that the majority’s extension <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong> went beyond<br />

Strauder and other equal protection precedents that involved exclusion <strong>of</strong> jurors <strong>of</strong> the<br />

defendant’s race. Id. at 417–18, 420, 422 (Scalia, J., dissenting).<br />

113. See id. at 406 (majority opinion).<br />

114. See id. at 404 (noting that a defendant suffers an equal protection deprivation when<br />

“members <strong>of</strong> his or her race have been excluded” from the jury).<br />

115. See id. at 411–15. A defendant suffered “cognizable injury” when a juror was excluded<br />

on account <strong>of</strong> race. Id. at 411. According <strong>to</strong> the Powers majority, race could not serve as “a proxy<br />

for . . . bias or competence” and had no relationship <strong>to</strong> juror fitness. Id. at 410. Stereotypebased<br />

strikes violated equal protection even if “members <strong>of</strong> all races” were struck on the basis <strong>of</strong><br />

assumptions rooted solely in race, because “racial classifications” are impermissible and “do not<br />

become legitimate” because all races “suffer them” equally. Id.<br />

116. Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co., 500 U.S. 614, 616 (1991).<br />

117. Id. at 616–17.<br />

118. Id. at 617.<br />

119. Id. at 630.

1408 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:1393<br />

standing <strong>to</strong> assert jurors’ rights. 120 The majority had no doubt that the harm<br />

<strong>to</strong> jurors in civil proceedings was as great as in criminal cases and believed<br />

that third-party standing <strong>to</strong> assert jurors’ rights was equally justified in civil<br />

suits. 121 Because only governmental conduct can violate constitutional rights,<br />

however, the pivotal question in Edmonson was whether a private party’s<br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ries constituted “state action.” 122 The majority found state action<br />

because the party is exercising “a right or privilege having its source in state<br />

authority,” 123 and because “a private litigant in all fairness must be deemed a<br />

government ac<strong>to</strong>r in the use <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges.” 124<br />

<strong>Batson</strong> and Edmonson meant that prosecu<strong>to</strong>rs, civil plaintiffs, and civil<br />

defendants could not strike jurors on account <strong>of</strong> race or race-based<br />

assumptions. Whether criminal defendants were also constrained remained<br />

an open question. The Court confronted that issue just one year later in<br />

Georgia v. McCollum. 125<br />

In McCollum, white defendants were charged with aggravated assault<br />

and simple battery against black victims. 126 The government sought a pretrial<br />

ruling prohibiting the defendants “from exercising peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges<br />

in a racially discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry manner.” 127 The lower courts held that <strong>Batson</strong> did<br />

not apply <strong>to</strong> defense peremp<strong>to</strong>ries. 128 Seven Justices disagreed, concluding<br />

that <strong>Batson</strong>’s equal protection restrictions govern defendants’ peremp<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

challenges. 129<br />

At the outset, Justice Blackmun highlighted “four questions” that<br />

required answers: whether a defendant’s race-based peremp<strong>to</strong>ries inflicted<br />

120. See id. at 618 (explaining these two underpinnings <strong>of</strong> Powers).<br />

121. Id. at 619.<br />

122. Id. at 619–20.<br />

123. Id. at 620–21.<br />

124. Id. at 621. Edmonson also emphasized the unacceptability <strong>of</strong> “the au<strong>to</strong>matic invocation<br />

<strong>of</strong> race stereotypes.” Id. at 630. Race-based generalizations that “cause injury <strong>to</strong> the excused<br />

juror[s]” cannot be justified by either “open hostility or . . . some hidden and unarticulated<br />

fear.” Id. at 631. If parties believe that jurors have “biases or instincts” that might influence their<br />

judgment, they should explore the issue “in a rational way that consists with respect for the<br />

dignity <strong>of</strong> persons, without the use <strong>of</strong> classifications based on ancestry or skin color.” Id.<br />

125. Georgia v. McCollum, 505 U.S. 42 (1992).<br />

126. Id. at 44.<br />

127. Id. at 44–45. The defense’s twenty peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges were sufficient <strong>to</strong> enable the<br />

exclusion <strong>of</strong> all black jurors. Id. at 45.<br />

128. Id. at 45.<br />

129. Id. at 59. Only six Justices joined the majority opinion, as Justice Thomas concurred<br />

only in the judgment. See id. at 60 (Thomas, J., concurring in the judgment). Moreover, two<br />

members <strong>of</strong> the majority agreed with the holding only because they believed that Edmonson<br />

dictated an extension <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong> <strong>to</strong> criminal defendants. See id. at 59–60 (Rehnquist, C.J.,<br />

concurring); id. at 60 (Thomas, J., concurring in the judgment). Both, however, expressed<br />

disagreement with Edmonson’s extension <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong>. Id. at 59–60 (Rehnquist, C.J., concurring);<br />

id. at 60 (Thomas, J., concurring in the judgment).

2012] TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF BATSON 1409<br />

<strong>Batson</strong> harms; whether defense peremp<strong>to</strong>ries constituted state action;<br />

whether prosecu<strong>to</strong>rs had standing <strong>to</strong> challenge defense peremp<strong>to</strong>ries; and<br />

whether defendants’ “constitutional rights . . . preclude[d] the extension” <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Batson</strong>. 130 He concluded that a defendant’s racially discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry strikes<br />

cause the same injuries <strong>to</strong> jurors and the community. 131 The Court<br />

acknowledged the adversarial relationship between a defendant and the<br />

state and the fact that an accused generally acts <strong>to</strong> serve private purposes,<br />

but still concluded that the exercise <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges <strong>to</strong> aid in jury<br />

selection constituted state action. 132 Moreover, it held that the reasoning <strong>of</strong><br />

Powers and Edmonson applied with equal, if not greater, force, justifying a<br />

decision <strong>to</strong> accord prosecu<strong>to</strong>rs third-party “standing <strong>to</strong> assert the excluded<br />

jurors’ rights.” 133<br />

Most significantly, the Court rejected the contention that “the interests<br />

served by <strong>Batson</strong> must give way <strong>to</strong> the rights <strong>of</strong> a criminal defendant.” 134<br />

Neither the fair-trial interests served by peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges nor the<br />

“Sixth Amendment right[s] <strong>to</strong> the effective assistance <strong>of</strong> counsel” and <strong>to</strong> “an<br />

impartial jury” required that defendants be free <strong>to</strong> remove jurors based on<br />

their race. 135 Although defendants have the right <strong>to</strong> keep jurors with bias or<br />

animus from sitting in judgment, 136 the Fourteenth Amendment does not<br />

permit them <strong>to</strong> further this interest in impartiality by “discriminat[ing]<br />

invidiously against jurors on account <strong>of</strong> race.” 137 Consequently, race-based<br />

assumptions and racial stereotyping could not support defense challenges. 138<br />

The majority believed that the bar <strong>to</strong> discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry challenges would not<br />

significantly impair an accused’s interests in a fair trial or the legitimate<br />

exercise <strong>of</strong> fundamental Sixth Amendment rights. 139 Moreover, the higher<br />

interest in preventing equal protection violations trumped any risk <strong>to</strong> a<br />

defendant’s rights. 140<br />

130. See id. at 48 (majority opinion).<br />

131. Id. at 48–50.<br />

132. Id. at 50–55. According <strong>to</strong> McCollum, the state-action determination “depends on the<br />

nature and context <strong>of</strong> the function [a defense at<strong>to</strong>rney] is performing.” Id. at 54. “The exercise<br />

<strong>of</strong> a peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenge differs significantly from other actions taken in support <strong>of</strong> a<br />

defendant’s defense” because “a criminal defendant is wielding the power <strong>to</strong> choose a<br />

quintessential governmental body—indeed, the institution <strong>of</strong> government on which our judicial<br />

system depends.” Id.<br />

133. Id. at 56.<br />

134. Id. at 57.<br />

135. Id. at 57–58.<br />

136. Id. at 58.<br />

137. Id. at 59.<br />

138. Id.<br />

139. See id. at 58.<br />

140. Id. at 57.

1410 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:1393<br />

The last expansion <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong>’s reach occurred in J.E.B. v. Alabama, 141<br />

eight years after <strong>Batson</strong>. The issue was “whether the Equal Protection Clause<br />

forbids intentional discrimination on the basis <strong>of</strong> gender” in the exercise <strong>of</strong><br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges. 142 J.E.B. involved a state’s claim for paternity and<br />

child support on behalf <strong>of</strong> a minor’s mother. 143 The defendant objected <strong>to</strong><br />

the State’s strikes <strong>of</strong> male jurors. 144 Six Justices disagreed with the lower<br />

courts’ rulings that <strong>Batson</strong> did not apply <strong>to</strong> gender-based strikes. 145 The<br />

majority concluded that because “gender, like race, is an unconstitutional<br />

proxy for juror competence and impartiality,” the Fourteenth Amendment<br />

forbids striking jurors based on gender or assumptions rooted in gender. 146<br />

The majority documented the long his<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>of</strong> wholesale exclusion <strong>of</strong><br />

women from jury service, a his<strong>to</strong>ry that lasted well in<strong>to</strong> the twentieth century<br />

and long after Strauder declared the exclusion <strong>of</strong> blacks unconstitutional. 147<br />

Precedent prescribed heightened equal protection scrutiny <strong>of</strong> gender-based<br />

classifications because <strong>of</strong> the danger <strong>of</strong> “‘archaic and overbroad’<br />

generalizations about gender” and “outdated misconceptions” about<br />

women’s roles. 148 Rejecting the contention that sex discrimination had never<br />

been as serious as race discrimination, the Court declared that “the<br />

similarities between the experiences <strong>of</strong> racial minorities and women” were<br />

much greater than the differences. 149<br />

This his<strong>to</strong>ry and the scrutiny afforded gender-based classifications<br />

meant that the sole issue was whether gender discrimination in jury<br />

selection “substantially furthers the . . . legitimate interest in achieving a fair<br />

and impartial trial.” 150 More specifically, the Court addressed “whether<br />

peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges based on gender stereotypes” substantially assist the<br />

“effort <strong>to</strong> secure a fair and impartial jury.” 151 The State’s contention that<br />

men could be “more sympathetic and receptive <strong>to</strong>” a paternity suit<br />

defendant was not “an exceptionally persuasive justification” but, instead,<br />

was a constitutionally forbidden stereotype. 152 It was “reminiscent <strong>of</strong> the<br />

141. J.E.B. v. Alabama ex rel. T.B., 511 U.S. 127 (1994).<br />

142. Id. at 129.<br />

143. Id.<br />

144. Id.<br />

145. Id.<br />

146. Id.<br />

147. Id. at 131.<br />

148. Id. at 135 (quoting Schlesinger v. Ballard, 419 U.S. 498, 506–07 (1975); Craig v.<br />

Boren, 429 U.S. 190, 198–99 (1976)) (internal quotation marks omitted from second<br />

quotation).<br />

149. Id.<br />

150. Id. at 136–37.<br />

151. Id. at 137.<br />

152. Id. at 137–38.

2012] TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF BATSON 1411<br />

arguments” supporting the prohibition <strong>of</strong> women jurors. 153 Moreover, the<br />

State had furnished “virtually no support for the conclusion that gender<br />

alone” accurately predicts juror attitudes and was wrong “<strong>to</strong> assume that<br />

gross generalizations” rooted in gender were any more permissible than<br />

those grounded in race. 154 Consequently, every person had a right against<br />

summary exclusion from jury service “because <strong>of</strong> discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry and<br />

stereotypical presumptions that reflect and reinforce patterns <strong>of</strong> his<strong>to</strong>rical<br />

discrimination.” 155<br />

J.E.B. addressed the border <strong>of</strong> <strong>Batson</strong>’s terri<strong>to</strong>ry, indicating that few, if<br />

any, other types <strong>of</strong> discrimination were regulated. While neither race nor<br />

gender may “serve as a proxy for bias,” a party may peremp<strong>to</strong>rily remove<br />

“any group or class <strong>of</strong> individuals normally subject <strong>to</strong> ‘rational basis’<br />

review.” 156 <strong>An</strong> equal protection challenge is possible only when peremp<strong>to</strong>ries<br />

target groups accorded higher-than-rational-basis equal protection<br />

scrutiny. 157<br />

In sum, in four significant decisions during <strong>Batson</strong>’s first decade, the<br />

Court expanded its reach. Defendants may raise claims based on the<br />

removal <strong>of</strong> jurors <strong>of</strong> a different race, neither civil parties nor criminal<br />

defendants may strike jurors based on race, and parties may not strike jurors<br />

based on gender. Having broadened its realm substantially, the Court then<br />

announced that the era <strong>of</strong> expansion was nearing—or was at—an end.<br />

B. REFINING BATSON’S DOCTRINE<br />

A few post-<strong>Batson</strong> decisions have refined the doctrinal framework<br />

prescribed for evaluating equal protection claims. As discussed above, <strong>Batson</strong><br />

established three steps. First, the opponent <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges must<br />

establish a prima facie case <strong>of</strong> purposeful discrimination. If a sufficient<br />

showing is made, step two requires the party exercising the contested<br />

153. Id. at 138.<br />

154. Id. at 138–40.<br />

155. Id. at 141–42. The Court noted that gender-based strikes inflict the same sorts <strong>of</strong><br />

harms that motivated <strong>Batson</strong> and “ratify and reinforce prejudicial views <strong>of</strong> the relative abilities <strong>of</strong><br />

men and women.” Id. at 140.<br />

156. Id. at 143.<br />

157. In general, the only other classifications that currently qualify for higher equal<br />

protection scrutiny are religion, see Larson v. Valente, 456 U.S. 228, 246 (1982); national<br />

origin, see Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633, 646 (1948); alienage, see Graham v. Richardson,<br />

403 U.S. 365, 376 (1971); and illegitimacy, see Clark v. Jeter, 486 U.S. 456, 465 (1988). In<br />

light <strong>of</strong> the unique his<strong>to</strong>ries <strong>of</strong> race and sex discrimination in jury selection, the majority<br />

suggested that <strong>Batson</strong>’s framework might apply only <strong>to</strong> strikes based on “race or gender.” See<br />

J.E.B., 511 U.S. at 142 n.14 (stating that “peremp<strong>to</strong>ry challenges . . . on the basis <strong>of</strong> group<br />

characteristics other than race or gender . . . do not reinforce the same stereotypes about the<br />

group’s competence or predispositions that have been used <strong>to</strong> prevent them from voting,<br />

participating on juries, pursuing their chosen pr<strong>of</strong>essions, or otherwise contributing <strong>to</strong> civic<br />

life”).

1412 IOWA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 97:1393<br />

challenges <strong>to</strong> rebut the inference <strong>of</strong> discrimination with an adequate<br />

explanation. Assuming rebuttal, in the crucial third step a judge must decide<br />

whether the objec<strong>to</strong>r carried the burden <strong>of</strong> proving intentional<br />

discrimination on race or gender grounds.<br />

The most significant doctrinal developments clarified the explanations<br />

that are sufficient <strong>to</strong> satisfy the rebuttal demand. Hernandez v. New York<br />

involved a Hispanic defendant’s objection <strong>to</strong> the prosecution’s strikes <strong>of</strong><br />

Hispanic jurors. 158 The prosecu<strong>to</strong>r explained that he struck bilingual jurors<br />

because <strong>of</strong> concerns that they might not be able <strong>to</strong> follow the <strong>of</strong>ficial<br />

interpreter’s translation <strong>of</strong> Spanish testimony and that “they would have an<br />

undue impact upon the jury.” 159 The lower courts deemed the explanation<br />

adequate. 160<br />

On review, the Supreme Court focused on <strong>Batson</strong>’s demand that the<br />

proponent <strong>of</strong> peremp<strong>to</strong>ry strikes “articulate a race-neutral explanation for<br />

striking the jurors in question,” concluding that reasons lack “race<br />

neutrality” if, assuming them true, the “challenges violate the Equal<br />

Protection Clause as a matter <strong>of</strong> law.” 161 Because discrimina<strong>to</strong>ry intent is<br />

necessary, a rebuttal reason is not unacceptable merely because it has a<br />

“racially disproportionate impact.” 162 At step two <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Batson</strong> “inquiry,” “the<br />

issue is . . . facial validity,” and an explanation “based on something other<br />

than the race <strong>of</strong> the juror” is a facially valid rebuttal. 163<br />

In Hernandez, the Court found the prosecu<strong>to</strong>r’s explanation for striking<br />

Hispanic jurors <strong>to</strong> be race-neutral. It did not reflect an “intention <strong>to</strong> exclude<br />

Latino or bilingual jurors” or “stereotypical assumptions about Latinos or<br />

bilinguals.” 164 Because it was rooted in concerns generated by the jurors’<br />

responses during voir dire, the rebuttal demand was met. 165<br />

Because the prosecution furnished a race-neutral reason, step three<br />

obligated the trial judge <strong>to</strong> decide whether the accused carried his burden<br />

<strong>of</strong> proving discrimination. 166 At this stage, a judge may consider the<br />

disproportionate exclusionary impact upon a racial or ethnic group as an<br />

158. Hernandez v. New York, 500 U.S. 352, 356 (1991) (plurality opinion).<br />