studies of the Pueblo Escultor - San Agustin Statues - Estatuas de ...

studies of the Pueblo Escultor - San Agustin Statues - Estatuas de ...

studies of the Pueblo Escultor - San Agustin Statues - Estatuas de ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

PUEBLO ESCULTOR<br />

Stone <strong>Statues</strong> from <strong>San</strong> Agustín and <strong>the</strong> Macizo<br />

Colombiano<br />

drawings and text by<br />

Davíd Dellenback

inspiración--inspiration<br />

"Sería bien interesante recoger y diseñar todas las piezas<br />

que se hallan esparcidas en los alre<strong>de</strong>dores <strong>de</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín.<br />

Ellas nos harían conocer el punto a que llevaron la escultura<br />

los habitantes <strong>de</strong> estas regiones, y nos manifestarían algunos<br />

rasgos <strong>de</strong> su culto y <strong>de</strong> su policía."<br />

["It would be very interesting to ga<strong>the</strong>r toge<strong>the</strong>r and<br />

illustrate all <strong>the</strong> statues that are found dispersed in <strong>the</strong> <strong>San</strong><br />

Agustín area. They would give us knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> point to<br />

which sculpture was <strong>de</strong>veloped by <strong>the</strong> inhabitants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se<br />

regions, and would manifest some traces <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir religion and <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir politics."]<br />

––Francisco José <strong>de</strong> Caldas, "Estado <strong>de</strong> la Geografía <strong>de</strong>l<br />

Virreinato <strong>de</strong> <strong>San</strong>ta Fe <strong>de</strong> Bogotá" in Semanario <strong>de</strong>l Nuevo Reino<br />

<strong>de</strong> Granada, 1808.<br />

*************************<br />

"Ojalá que mi esploración...<strong>de</strong>spierte la voluntad <strong>de</strong><br />

nuestros anticuarios i los <strong>de</strong>termine a esculcar, auxiliados por<br />

trabajadores, los rincones <strong>de</strong> aquel valle misterioso i las<br />

ruinas que no me fue posible [<strong>de</strong>stapar]. La arqueolojía i la<br />

historia antigua <strong>de</strong> este país ganaría mucho en ello, porque en<br />

mi concepto no tienen número las preciosida<strong>de</strong>s que podrían<br />

<strong>de</strong>senterrarse...i que juntas como las pájinas <strong>de</strong> un libro, ahora<br />

<strong>de</strong>sencua<strong>de</strong>rnado, referirían hechos que los cronistas <strong>de</strong> la<br />

conquista no pudieron ver o no supieron transmitir."<br />

["I hope that my exploration awakens <strong>the</strong> will <strong>of</strong> our<br />

stu<strong>de</strong>nts <strong>of</strong> ancient culture and stimulates <strong>the</strong>m to search, with<br />

<strong>the</strong> aid <strong>of</strong> local workers, <strong>the</strong> corners <strong>of</strong> that mysterious valley,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> ruins which I was not able to uncover. The archaeology<br />

and ancient history <strong>of</strong> this country would gain much by it,<br />

because in my opinion <strong>the</strong>re are innumerable objects <strong>of</strong> value and<br />

beauty which could be unear<strong>the</strong>d and which, ga<strong>the</strong>red toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

like <strong>the</strong> pages <strong>of</strong> a book, as yet unbound, would tell us <strong>of</strong><br />

realities that <strong>the</strong> chroniclers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> conquest could not see or<br />

did not know how to relate."]<br />

––Agustín Codazzi, "Antigueda<strong>de</strong>s Indíjenas––Ruinas <strong>de</strong> <strong>San</strong><br />

Agustín" in Jeografía Física y Política <strong>de</strong> los Estados Unidos <strong>de</strong><br />

Colombia (Volume II), p 92, by Dr. Felipe Pérez, 1857.

table <strong>of</strong> contents<br />

Inspiration: Caldas and Codazzi…………………………………… 5<br />

Introduction ………………………………………………………… 9<br />

1. The Macizo Colombiano and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>………………. 15<br />

2. Studies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>…………………………………… 41<br />

<strong>San</strong>ta Gertrudis; Caldas; <strong>de</strong> Rivero & von Tschudi; Codazzi; Stübel; André;<br />

Chaffanjon; Gutiérrez <strong>de</strong> Alba; Cuervo Márquez; Stöpel; Preuss; Trujillo &<br />

Montealegre; Lunardi; Wavrin; Wal<strong>de</strong>-Wal<strong>de</strong>gg; Hernán<strong>de</strong>z <strong>de</strong> Alba; Pérez<br />

<strong>de</strong> Barradas; Silva Célis; Rivet; Duque Gómez; Reichel-Dolmat<strong>of</strong>f; Cháves &<br />

Puerta; Llanos Vargas; Drennan.<br />

3. The <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> and American Traditions………………….. 67<br />

Introduction to this study; Introduction to our chosen image; Six doublings;<br />

Cristóbal <strong>de</strong> Molina; Introduction to <strong>the</strong> survey; Olmec; Mesoamerica; Aztec;<br />

Central America; Chavín; Titicaca Basin; Tiwanaku; Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Perú.<br />

4. Categories………………………………………………………... 137<br />

One: The Serpent; Two: Woman; Three: Male Signs; Four: Sacrifice Figures;<br />

Five: Doble Yo; Six: The Feline; Seven: Cayman/Rana/Lagarto; Eight: Bird<br />

Figures; Nine: O<strong>the</strong>r Animals; Ten: Coqueros; Eleven: Masked Figures;<br />

Twelve: Lengua/Cinta/Cabeza; Thirteen: O<strong>the</strong>r Implements in Hands;<br />

Fourteen: Death Posture; Fifteen: Several O<strong>the</strong>r Categories; followed by Lists <strong>of</strong><br />

Categories.<br />

5. The Creation <strong>of</strong> This Catalogue………………………………….. 237<br />

6. Footnotes to Text…………………………………………………. 251<br />

7. Bibliographies…………………………………………………….. 257<br />

Key Bibliography; General Bibliography; Tierra<strong>de</strong>ntro Area Bibliography;<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> Areas Bibliography; French Bibliography; German<br />

Bibliography; English Bibliography.

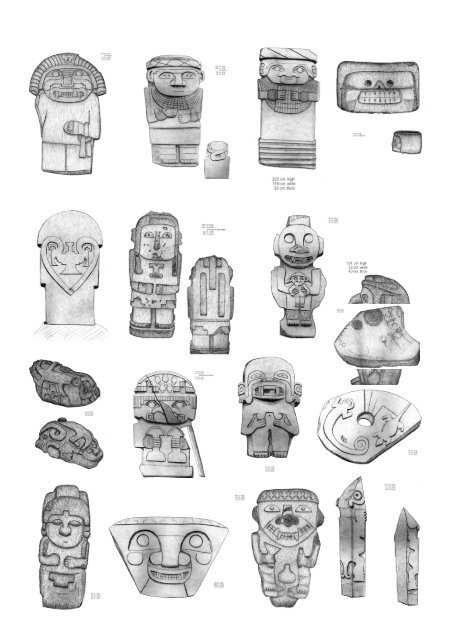

drawing by Henk van <strong>de</strong>r Eer<strong>de</strong>n 1978

INTRODUCTION<br />

This is <strong>the</strong> book <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>; <strong>the</strong> name (which is spanish for ‘The<br />

Sculpting People’ or ‘The Sculptors’) refers to <strong>the</strong> Statue-Makers who many<br />

centuries ago inhabited <strong>the</strong> flanks and valleys <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo Colombiano, <strong>the</strong> great<br />

massif or mountainous knot in <strong>the</strong> southwest <strong>of</strong> what is now Colombia, and buried<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir monoliths in subterranean tomb-complexes. The statue-makers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong><br />

<strong>Escultor</strong> were <strong>the</strong> authors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> greatest and most extensive library <strong>of</strong> stone<br />

images ever created in precolumbian America, and <strong>the</strong> book before you represents<br />

<strong>the</strong> presentation, <strong>the</strong> revelation, <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> imagery <strong>of</strong> this fabulous stone library.<br />

So, to <strong>de</strong>lve into <strong>the</strong> heart <strong>of</strong> this study, turn to <strong>the</strong> pages <strong>of</strong> images, <strong>the</strong><br />

drawings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stone statues <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>. Make <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m what you will.<br />

The rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> information in this book is subsidiary and concomitant; perusal <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> drawings and meditation on <strong>the</strong>se ancient images will facilitate a glimpse into a<br />

vanished (and yet not completely dispelled) realm essentially forgotten by today’s<br />

mo<strong>de</strong>rn world, and basically unknown even to most experts in <strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong><br />

precolumbian archaeology.<br />

The name ‘<strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>’ will fail to ring a bell with <strong>the</strong> great majority <strong>of</strong><br />

rea<strong>de</strong>rs and stu<strong>de</strong>nts, some <strong>of</strong> whom at least will associate <strong>the</strong> label ‘<strong>San</strong> Agustín’<br />

with <strong>the</strong> statues and images here displayed. But this latter appellation is<br />

misconceived for two principal reasons. First: while it is true that <strong>the</strong> valley<br />

surrounding <strong>the</strong> town <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín is home to a great number <strong>of</strong> statues—more<br />

than ⅔ <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> total consi<strong>de</strong>red in this survey were found in <strong>the</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín area—<br />

none<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong> consi<strong>de</strong>rable remain<strong>de</strong>r were elaborated and buried elsewhere in<br />

<strong>the</strong> lands <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo Colombiano. Important nuclei <strong>of</strong> statues such as<br />

Tierra<strong>de</strong>ntro, Moscopan, Platavieja and o<strong>the</strong>rs are located far from <strong>San</strong> Agustín,<br />

and yet clearly and unmistakably—in style, in substance, and in spirit—represent<br />

<strong>the</strong> world <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>.<br />

And second, it is reasonable—and accords with <strong>the</strong> method ruling <strong>the</strong><br />

application <strong>of</strong> nomenclature to archaeological sites and cultures—that <strong>the</strong> names <strong>of</strong><br />

living, present-day towns and peoples are not to be given to archaeological vestiges<br />

and locations. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, <strong>the</strong> ‘culture <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín’ is not a historical relic<br />

that once existed in <strong>the</strong> past, but ra<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> living entity that inhabits <strong>the</strong> valley <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>San</strong> Agustín today, and is comprised <strong>of</strong> campesinos, c<strong>of</strong>fee farmers, shopkeepers,<br />

dayworkers, auto mechanics, city employees, housewives, schoolchildren and<br />

teachers, <strong>de</strong>ntists and doctors, soccer players, huaqueros, expatriate foreigners,<br />

and so on. The ancient culture, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, <strong>the</strong> makers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> statues, <strong>the</strong><br />

authors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> earthworks and tomb-structures and ceramics and o<strong>the</strong>r vestiges that<br />

we can still perceive today, who lived and wrought in this and o<strong>the</strong>r Macizo

valleys many centuries before <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> town <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín—<strong>the</strong>se<br />

ancient statue-makers must have <strong>the</strong>ir own handle. I call <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>.<br />

And I am not alone in so doing, nor did this name originate with my <strong>studies</strong>.<br />

Carlos Cuervo Márquez, <strong>the</strong> first colombian to publish a <strong>de</strong>tailed <strong>de</strong>scription <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se antiquities, coined <strong>the</strong> term ‘<strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>’ to refer to <strong>the</strong> statue-makers in<br />

1892, and K. Th. Preuss, <strong>the</strong> eminent german archaeologist who first brought <strong>the</strong>se<br />

tremendous monoliths to <strong>the</strong> wi<strong>de</strong>r world’s notice, used <strong>the</strong> name in his classic<br />

1929 volume whose title translates as Prehistoric Monumental Art (later published<br />

in spanish, but never in english). Given that Agustín Codazzi’s groundbreaking<br />

study was <strong>the</strong> only published monograph preceding Cuervo Márquez to <strong>de</strong>al with<br />

<strong>the</strong>se statues in any <strong>de</strong>tail, it is fair to say that our title has been in <strong>the</strong> literature<br />

virtually since <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> our awareness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se people and <strong>the</strong>ir art.<br />

<strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> it is, <strong>the</strong>n.<br />

As I say, look first, and principally, at <strong>the</strong> drawings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> monoliths. This<br />

book is above all a catalogue, as complete as possible, <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong><br />

statues. Secondly, be aware that each statue is accompanied by a ‘card,’ which is a<br />

page <strong>of</strong> basic data; <strong>the</strong> ‘card number’ referenced is printed at <strong>the</strong> foot <strong>of</strong> each<br />

drawing. By referring to <strong>the</strong> given card, <strong>the</strong> rea<strong>de</strong>r will add, to <strong>the</strong> visual image,<br />

associated knowledge: dimensions, original location, present location (though it’s<br />

been 15 years and more since that “present”), bibliographical trail, a brief<br />

<strong>de</strong>scriptive title. And in a more subjective manner, <strong>the</strong> card also lists <strong>the</strong><br />

categories (examined in chapter four) into which <strong>the</strong> particular statue falls, and <strong>the</strong><br />

specific analogs to <strong>the</strong> given statue: <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r images which may be fruitfully<br />

compared and associated. The observer unfamiliar with <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> who<br />

makes use <strong>of</strong> this ‘category’ and ‘analog’ information will hopefully find it useful<br />

in providing a general orientation and method <strong>of</strong> study.<br />

This project was carried out some significant time ago, and <strong>the</strong> term ‘cards’<br />

is a nostalgic nod to an anachronistic method—but one that, none<strong>the</strong>less, teaches a<br />

good bit, however tedious and repetitive <strong>the</strong> act <strong>of</strong> writing and erasing and <strong>the</strong>n<br />

reflecting and rewriting on a little paper card may be—in <strong>the</strong> same way that<br />

drawing a picture ra<strong>the</strong>r than snapping a photo may not always produce a superior<br />

image on paper, but it will surely do so in <strong>the</strong> mind, and one that may be richer and<br />

<strong>de</strong>eper in experience, too.<br />

To turn, now, to a glance at <strong>the</strong> text <strong>of</strong> this book: <strong>the</strong> first chapter begins<br />

with an attempt to place <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> within a <strong>de</strong>scription <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir natural<br />

environment, that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo Colombiano and <strong>the</strong> reaches <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> an<strong>de</strong>an<br />

cordilleras that surround <strong>the</strong> Macizo. With this vision in place, <strong>the</strong>re follows a<br />

<strong>de</strong>tailing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> different nuclei or site-areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> within that<br />

world, <strong>the</strong> emerald, tropical, many-rivered world <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo. The rea<strong>de</strong>r will

find, at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> this section, <strong>the</strong> assertion that “The statues may have been<br />

created over a period <strong>of</strong> up to, or even more than, one thousand years.” Take this<br />

statement, please, as an admission <strong>of</strong> what will not be found in this book.<br />

What will not be found here—what would in<strong>de</strong>ed be appropriate at this<br />

point—is a wi<strong>de</strong>-ranging, learned discourse on this archaeological entity, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>, authored by a well-trained and very acute pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

archaeologist, who would be able to dig into <strong>the</strong> documented remains <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

ancient statue-makers and artfully present <strong>the</strong>m for us against a background <strong>of</strong><br />

mastery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> context, <strong>the</strong> precolumbian world. Believe me, I would love to read<br />

such a study myself; it is sadly lacking. The fact that it simply doesn’t exist stands<br />

as one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> major prompts which led me into <strong>the</strong> labyrinth <strong>of</strong> my own <strong>studies</strong>, a<br />

maze that I hope now to be exiting with <strong>the</strong> presentation <strong>of</strong> this effort. But <strong>the</strong> fact<br />

remains, that I am not that person; no resumo los requisitos, as <strong>the</strong> phrase runs in<br />

spanish. I am not <strong>the</strong> master <strong>of</strong> that knowledge. My life in Colombia and in <strong>the</strong><br />

Macizo Colombiano has led me to conclu<strong>de</strong> that a lifetime is remarkably short, that<br />

one can spend <strong>the</strong> years and enmesh oneself in <strong>the</strong> web that leads to graduate<br />

<strong>de</strong>grees and pr<strong>of</strong>essional attributes and knowledge (assuming one has <strong>the</strong> skills to<br />

do so), or one can live and brea<strong>the</strong>, and laugh and curse, <strong>the</strong> life <strong>of</strong> an adopted<br />

culture, and make it full-time one’s own; but it is little likely that one will do both.<br />

The published literature on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> (by whatever name) simply<br />

isn’t satisfying enough or up-to-date, at this point. The classic work—that <strong>of</strong><br />

Preuss—dates, unfortunately, from 1929, and its author saw less than one-fourth <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> lithic statues available in <strong>the</strong> present survey. In addition, while Preuss gives us<br />

much raw data that remains valuable, his context and his analysis are somewhat<br />

laughable, and not <strong>of</strong> much use, and in addition, <strong>the</strong> book never appeared in<br />

english. The two major ‘mo<strong>de</strong>rn’ works both date from <strong>the</strong> 1960’s, and thus are<br />

nearing <strong>the</strong> half-century mark in age without having been notably bettered by any<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r updated publication. One is by Duque Gómez, who was virtually an<br />

archaeological caudillo in Colombia, and remains an icon to today’s colombian<br />

elite in his field, but frankly, his research, while again proportioning reams <strong>of</strong><br />

useful raw data, is confusing and mostly useless (and in addition, <strong>of</strong> course, quite<br />

unavailable in spanish, and nonexistent in english). The best book in <strong>the</strong> field,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n, is Reichel-Dolmat<strong>of</strong>f’s <strong>San</strong> Agustín: A Culture <strong>of</strong> Colombia, published in<br />

1966, in english; <strong>the</strong> rea<strong>de</strong>r who seeks <strong>the</strong> best archaeological study <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong><br />

<strong>Escultor</strong> must still search out this excellent, if outdated, volume.<br />

Chapter one closes with a brief glimpse <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lands <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong><br />

after <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>de</strong>mise, between <strong>the</strong>ir disappearance and <strong>the</strong> 16 th -century european<br />

invasion <strong>of</strong> America. The second chapter presents a history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>, from <strong>the</strong> first mention <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> antiquities in print, penned by <strong>the</strong><br />

wan<strong>de</strong>ring franciscan friar Juan <strong>de</strong> <strong>San</strong>ta Gertrudis in 1757, up through <strong>the</strong><br />

publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1980’s. The quina boom <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> late 19 th century, we will see,

provi<strong>de</strong>d <strong>the</strong> trigger that led to <strong>the</strong> unearthing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> flood <strong>of</strong> monoliths we are now<br />

able to observe and analyze. The contributions <strong>of</strong> such authors as Codazzi, Cuervo<br />

Márquez, Preuss, Pérez <strong>de</strong> Barradas, Hernán<strong>de</strong>z <strong>de</strong> Alba, Duque Gómez and<br />

Reichel Dolmat<strong>of</strong>f are covered, as well as those <strong>of</strong> many o<strong>the</strong>r stu<strong>de</strong>nts.<br />

This chapter attempts to throw light on <strong>the</strong> process that led to <strong>the</strong> progressive<br />

discovery <strong>of</strong> all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> different <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> statue-nuclei, and not just <strong>the</strong><br />

statues near <strong>the</strong> town <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín; and on <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>velopments that saw <strong>the</strong><br />

marvelous statue complexes in Tierra<strong>de</strong>ntro, Platavieja, Moscopan, Aguabonita,<br />

Saladoblanco, Nariño and Popayán progressively marginalized and ignored, while<br />

<strong>the</strong> focus intensified on <strong>the</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín monoliths. The present catalogue <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> images is an attempt to redress that skewed balance.<br />

With chapter three, we dig in to my own analyses <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> statues that I have<br />

studied for so many years. The background is <strong>the</strong> entire tableaux <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> creation <strong>of</strong><br />

lithic sculpture in precolumbian America—in Mesoamerica, in <strong>the</strong> An<strong>de</strong>s, and in<br />

<strong>the</strong> intermediate zone between <strong>the</strong>m, which inclu<strong>de</strong>s <strong>the</strong> Macizo Colombiano—and<br />

against this tapestry I attempt to point <strong>the</strong> way to valid comparisons, in style, in<br />

substance and in function, that allow us to glimpse <strong>the</strong> meanings behind <strong>the</strong> wealth<br />

<strong>of</strong> iconography that teems in this remarkable statuary. The alphabet <strong>of</strong> this<br />

incredible stone library, <strong>the</strong> language <strong>of</strong> its revelations, has been only imperfectly<br />

approached up until now, its <strong>de</strong>pths only very casually plumbed; and since <strong>the</strong><br />

curtain came down on our protagonists, <strong>the</strong> makers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> statues, five centuries<br />

before <strong>the</strong> coming <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> european invasion, an un<strong>de</strong>rstanding <strong>of</strong> this iconography<br />

<strong>de</strong>pends to a large <strong>de</strong>gree on a grasp <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> background context. Hopefully this<br />

look at <strong>the</strong> possible relationships between <strong>the</strong>se Macizo statues and <strong>the</strong> stonecarvings<br />

created elsewhere across <strong>the</strong> breadth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> american continent throughout<br />

<strong>the</strong> sweep <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> high culture will aid in <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>cipherment <strong>of</strong> this<br />

passionate communication from <strong>the</strong> ancient past.<br />

In chapter four, I attempt to group <strong>the</strong> different statues in categories that<br />

allow us to try and take <strong>the</strong>m in and penetrate <strong>the</strong>m. Hopefully, a consi<strong>de</strong>ration <strong>of</strong><br />

my category groupings will assist future stu<strong>de</strong>nts in arranging <strong>the</strong>ir own ways <strong>of</strong><br />

comparing and contrasting <strong>the</strong> statues. The point is, <strong>the</strong>re are more than 460<br />

images at play here, which translates into a huge, confusing welter for any<br />

observer, especially <strong>the</strong> principiante. Some method <strong>of</strong> classification and<br />

codification is necessary for consi<strong>de</strong>red observation not to become a blur.<br />

I have attempted to approach this task as rigidly and ma<strong>the</strong>matically as<br />

possible. It is fine to note that <strong>the</strong>re are many serpents portrayed in <strong>the</strong> stones <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>; but are <strong>the</strong>re, really? How many is many? Can we be sure we<br />

are seeing serpents, or is <strong>the</strong> i<strong>de</strong>ntification merely apparent, or likely? And in what<br />

contexts do we see <strong>the</strong>m? Do <strong>the</strong>y always appear in <strong>the</strong> same context, alongsi<strong>de</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> same companion symbols? Do we see more, or less, birds in <strong>the</strong> lithic

imagery? In what contexts? Felines? Monkeys? Frogs? After we have asked and<br />

answered some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se questions, we may be able to put ourselves in <strong>the</strong> position<br />

<strong>of</strong> asking <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>eper questions: What are we being told here? Why do we think<br />

so? How sure can we be?<br />

How many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> statues are anthropomorphic? Can we tell which are<br />

female and which male? How many represent each gen<strong>de</strong>r, and why can we feel<br />

confi<strong>de</strong>nt in saying so? In what contexts do we find male and female? What<br />

iconography accompanies each? [We will learn that, surprisingly, <strong>the</strong>re are<br />

virtually no stone images <strong>of</strong> females in all <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> South America, and that <strong>the</strong><br />

tremendous set <strong>of</strong> stone females created by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> stands as one <strong>of</strong> its<br />

most striking and important features.] The question <strong>of</strong> items held in <strong>the</strong> hands <strong>of</strong><br />

human-shaped personages will take on great importance in our attempt to group<br />

and analyze <strong>the</strong> statues. What do <strong>the</strong>y hold? What is <strong>the</strong> meaning? How sure can<br />

we be?<br />

The important series <strong>of</strong> coca-chewers with <strong>the</strong>ir coca appurtenances are a<br />

vivid and peerless glance at <strong>the</strong> great, timeless sacrament <strong>of</strong> an<strong>de</strong>an<br />

spirituality………and <strong>the</strong>re are figures holding what appear to be<br />

weapons……..<strong>the</strong> little childlike ‘horned’ figures held in <strong>the</strong> hands <strong>of</strong><br />

adults……..<strong>the</strong> ‘staff-and-mask’ figures who hi<strong>de</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir true faces behind<br />

masks……..<strong>the</strong> famed ‘Doble-Yo’ or ‘Double-I’ figure, long consi<strong>de</strong>red iconic <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> people………<strong>the</strong> ‘lodges’ that appear to represent<br />

buildings………<strong>the</strong> ‘feline procreator’ and his human female partner…………. <strong>the</strong><br />

bird grasping a serpent in its talons and beak……….<strong>the</strong> mysterious figure that<br />

holds its own protruding tongue, which in turn seems to transform into something<br />

else……..<br />

The images are legion. Some method <strong>of</strong> analysis is necessary to even begin<br />

to make any sense <strong>of</strong> this great stone library. The systematic groupings in chapter<br />

four, when used in concert with <strong>the</strong> information ‘cards’ and while searching <strong>the</strong><br />

images, may prove to be <strong>of</strong> great value. There is, in addition, at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> text<br />

chapters, an extensive bibliography; when I finished compiling it, I would have<br />

consi<strong>de</strong>red it <strong>de</strong>finitive. Almost two <strong>de</strong>ca<strong>de</strong>s have passed since that date, however,<br />

so it is could no longer be called so; for <strong>the</strong> time period it covers, however, it is<br />

certainly close to complete. Appen<strong>de</strong>d sections fine-tune <strong>the</strong> bibliography, too,<br />

into french, german and english sources, and listings <strong>de</strong>tailing sources for <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> sites not found in <strong>the</strong> valley <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín.<br />

Davíd Dellenback<br />

April, 2008

<strong>the</strong> macizo colombiano<br />

In or<strong>de</strong>r to focus our attention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>, <strong>the</strong><br />

Statue-Making People who were <strong>the</strong> creators and sculptors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

vast tableaux <strong>of</strong> stone statues that form <strong>the</strong> axis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> present<br />

study, we must look closely at <strong>the</strong> world in which <strong>the</strong>y were<br />

born. It is <strong>the</strong> world <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo Colombiano—<strong>the</strong> Colombian<br />

Massif—<strong>the</strong> great mountainous knot in <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rnmost reaches <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> colombian An<strong>de</strong>s, not far from Colombia’s bor<strong>de</strong>r with<br />

Ecuador. Today, <strong>the</strong> states (or <strong>de</strong>partamentos) <strong>of</strong> Huila, Cauca<br />

and Nariño divi<strong>de</strong>, on paper, <strong>the</strong> unity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo. With or<br />

without an overlay <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>oretical divisions, however, <strong>the</strong> Macizo<br />

sits astri<strong>de</strong> <strong>the</strong> vast mountainous spine <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

continent like a huge knot in <strong>the</strong> warp <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> an<strong>de</strong>an system, and<br />

is called, because <strong>of</strong> this, <strong>the</strong> ‘Nudo Andino,’ or An<strong>de</strong>an Knot.<br />

It is a <strong>de</strong>fining point <strong>of</strong> articulation between two very<br />

different worlds.<br />

To <strong>the</strong> south is <strong>the</strong> land <strong>of</strong> Tahuantinsuyu, <strong>the</strong> ‘Four<br />

Quarters’ into which <strong>the</strong> Incas (and doubtlessly o<strong>the</strong>r, earlier<br />

rulers/patrones) would conceptually divi<strong>de</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir world, and<br />

which en<strong>de</strong>d where <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn reaches <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo began. It<br />

is <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rnmost sector <strong>of</strong> what we today call <strong>the</strong> Central<br />

An<strong>de</strong>s, in which <strong>the</strong> massive range has a unitary aspect, with few<br />

wi<strong>de</strong> lowland valleys to divi<strong>de</strong> it into separate cordilleras,<br />

running southward through Ecuador and Perú, toward Bolivia and<br />

<strong>the</strong> altiplano. The Macizo Colombiano (and lands northward) lay<br />

outsi<strong>de</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bor<strong>de</strong>rs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘Four Quarters.’<br />

The An<strong>de</strong>s to <strong>the</strong> north <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo are distinct from<br />

<strong>the</strong> mountains to <strong>the</strong> south in <strong>the</strong> sense that northward <strong>the</strong><br />

an<strong>de</strong>an chain breaks up into three separate cordilleras which no

longer form one cohesive barrier, but ra<strong>the</strong>r fragment a much<br />

broa<strong>de</strong>r area <strong>of</strong> mountains into innumerable different micro-<br />

systems, countless valleys and slopes and plains, river-valley<br />

<strong>de</strong>serts and tropical jungles and high-mountain páramos. The<br />

mountain systems in Colombia are lower than those to <strong>the</strong> south,<br />

and in addition <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn An<strong>de</strong>s are fully within <strong>the</strong> tropical<br />

zone, so that <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se mountains is florescent and<br />

green, with only isolated instances <strong>of</strong> extremely high snow-<br />

covered ridges and peaks. These colombian An<strong>de</strong>s “…unfold like a<br />

splendid multicolored fan, spreading out its mountains and<br />

valleys from <strong>the</strong> evergreen tropics to <strong>the</strong> bleak and cold<br />

highlands, from arid, wind-blown <strong>de</strong>serts to <strong>the</strong> lush, temperate<br />

slopes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> subtropical zone.” 1<br />

The Macizo Colombiano, which conjoins <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn and<br />

Central An<strong>de</strong>s, also forms <strong>the</strong> point <strong>of</strong> union, <strong>the</strong> zone in which<br />

<strong>the</strong> three separate cordilleras, running nearly parallel to each<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r north-south <strong>the</strong> length <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Colombia, converge to form<br />

<strong>the</strong> great mountain knot. These tripartite An<strong>de</strong>s (known as <strong>the</strong><br />

Cordillera Occi<strong>de</strong>ntal, <strong>the</strong> Cordillera Central and <strong>the</strong> Cordillera<br />

Oriental) gave birth to <strong>the</strong> many and variegated an<strong>de</strong>an worlds<br />

whose extreme physical diversity would be reflected in <strong>the</strong><br />

diverse precolombian peoples <strong>of</strong> Colombia. The An<strong>de</strong>s here are<br />

flanked on both si<strong>de</strong>s by tropical lowlands. On <strong>the</strong> west are <strong>the</strong><br />

low, impenetrable jungles <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Pacific coast. To <strong>the</strong> east <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Cordillera Oriental lie <strong>the</strong> plains <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Orinoco<br />

headwaters, known to colombians today as <strong>the</strong> llanos, and fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

south <strong>the</strong> beginnings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Amazon basin in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

headwaters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Caquetá and Putumayo Rivers. Within this<br />

tropical frame, <strong>the</strong> three cordilleras <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> an<strong>de</strong>an world are<br />

divi<strong>de</strong>d by two extremely long river valleys, those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cauca

and <strong>the</strong> Magdalena, which take <strong>the</strong>ir waters south-to-north <strong>the</strong><br />

length <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country.<br />

The life <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo, whose numerous high places are over<br />

4000 meters in altitu<strong>de</strong>, is <strong>de</strong>termined by its equatorial<br />

position, less than two <strong>de</strong>grees north <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> equator. Altitu<strong>de</strong>s<br />

this extreme in <strong>the</strong> peruvian cordillera might commonly be snow-<br />

covered, while ranges <strong>of</strong> even half that height in <strong>the</strong> north <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> North American continent are <strong>of</strong>ten wild, snow-blown and<br />

uninhabited. In <strong>the</strong> south <strong>of</strong> Colombia, though, given this<br />

proximity to <strong>the</strong> equatorial line, <strong>the</strong> situation is different,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo receives snow, if at all, only<br />

briefly during periods <strong>of</strong> storm. A number <strong>of</strong> great volcanic<br />

cones in <strong>the</strong> area, raised up above <strong>the</strong> surrounding heights <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> cordillera, are snow-covered peaks, such as <strong>the</strong> Puracé<br />

Volcano, just where <strong>the</strong> Cordillera Central is subsumed into <strong>the</strong><br />

Macizo. But <strong>the</strong> greater part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> highest land in <strong>the</strong> Macizo<br />

conforms features known as páramos: exceedingly cold and wet<br />

wil<strong>de</strong>rnesses at extremely high altitu<strong>de</strong>s which are at <strong>the</strong> same<br />

time bleak, in that <strong>the</strong>y are solitary, forbidding and <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

shrou<strong>de</strong>d in mist, and yet luxuriant, covered with a flourishing<br />

and uniquely strange vegetation particular to <strong>the</strong>se islands <strong>of</strong><br />

relatively flat, very high land.<br />

A string <strong>of</strong> such páramos is situated in <strong>the</strong> heights <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

An<strong>de</strong>an Knot and along <strong>the</strong> apices <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> different cordilleras<br />

which extend northward from this point <strong>of</strong> junction. Colombia’s<br />

latitu<strong>de</strong> is such that <strong>the</strong>re are many separate páramos in <strong>the</strong><br />

country, and more than 20 examples <strong>of</strong> this peculiar high<br />

ecosystem in <strong>the</strong> southwest <strong>of</strong> Colombia alone; <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>the</strong>y form<br />

solitary islands set among higher mountains and lower habitable<br />

zones, while o<strong>the</strong>r páramos bor<strong>de</strong>r on each o<strong>the</strong>r and form long

stretches <strong>of</strong> interlocked and adjacent wil<strong>de</strong>rness. Near <strong>the</strong><br />

convergence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cordillera Central and <strong>the</strong> mass <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo<br />

are located <strong>the</strong> Páramo <strong>de</strong> las Papas, <strong>the</strong> Páramo <strong>de</strong>l Letrero, <strong>the</strong><br />

Páramo <strong>de</strong> Cutanga and <strong>the</strong> Páramo <strong>de</strong> la Soledad, forming nearly a<br />

contiguous chain; along with <strong>the</strong> Páramo <strong>de</strong> Coconuco and <strong>the</strong><br />

Páramo <strong>de</strong> las Delicias not far away to <strong>the</strong> north-east, <strong>the</strong>y echo<br />

<strong>the</strong> present-day bor<strong>de</strong>r between <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>partamentos <strong>of</strong> Huila and<br />

Cauca.<br />

All páramos are extremely wet, and being at <strong>the</strong> tops <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

cordilleras, function naturally as sources <strong>of</strong> water. But <strong>the</strong><br />

páramos near this Macizo junction are such extraordinary water<br />

sources that <strong>the</strong>re can be few places on <strong>the</strong> planet where such a<br />

fantastic volume <strong>of</strong> water is born in such a limited space <strong>of</strong><br />

land. Colombia’s longest and principal river, <strong>the</strong> Magdalena,<br />

begins on <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn edge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo, issuing forth from<br />

two small lakes named La Magdalena and <strong>San</strong>tiago, first running<br />

west precipitously down <strong>the</strong> Macizo slopes to <strong>the</strong> valley or<br />

meseta <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín—by which time it is a thun<strong>de</strong>ring and<br />

dangerous wild-mountain river carrying a great volume <strong>of</strong> water—<br />

and <strong>the</strong>n continuing on west to near <strong>the</strong> town <strong>of</strong> Pitalito where,<br />

having left <strong>the</strong> cordillera behind and entered <strong>the</strong> broad central<br />

valley, <strong>the</strong> Magdalena curves to <strong>the</strong> north and begins its<br />

successively hotter and more leisurely course to <strong>the</strong> distant<br />

Caribbean, some 1800 kilometers away.<br />

The <strong>San</strong> Agustín native and scholar Don Tiberio López,<br />

writing, as he tells us, “…because I know <strong>the</strong>se places inch by<br />

inch…” 2 goes on to <strong>de</strong>scribe <strong>the</strong> birth <strong>of</strong> Colombia’s o<strong>the</strong>r great<br />

rivers on <strong>the</strong> páramos <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo: only two kilometers to <strong>the</strong><br />

south-east <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Magdalena’s birthplace, five small lakes join<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir waters to give birth to <strong>the</strong> Caquetá River. This major

affluent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Amazon bursts forth from <strong>the</strong> earth and flows<br />

south <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> slopes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo before eventually curving to<br />

<strong>the</strong> east and continuing on to traverse <strong>the</strong> entire breadth <strong>of</strong><br />

Colombia, <strong>the</strong>n entering Brazil, and flowing eastward through<br />

South America’s vast lowland basin. When it finally enters <strong>the</strong><br />

Amazon River, it has covered more than 1800 kilometers in its<br />

course from its birthplace on <strong>the</strong> Macizo Colombiano.<br />

Only five kilometers from <strong>the</strong> birthplace <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Magdalena a<br />

small river, <strong>the</strong> Pancitará, is born, and mingling its waters<br />

with a series <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r small rivers flowing <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> western<br />

slopes <strong>of</strong> this same chain <strong>of</strong> páramos gives birth to <strong>the</strong> Patía<br />

River which, running west and <strong>the</strong>n south, passes through <strong>the</strong><br />

states <strong>of</strong> Cauca and Nariño, and on to <strong>the</strong> Pacific Ocean, having<br />

journeyed some 400 kilometers. So we see that <strong>the</strong>se three<br />

rivers, born with a handful <strong>of</strong> kilometers <strong>of</strong> each o<strong>the</strong>r, flow in<br />

three separate directions, <strong>the</strong> Magdalena north to <strong>the</strong> Caribbean,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Caquetá east to joint <strong>the</strong> Amazon from whence on to <strong>the</strong><br />

Atlantic, and <strong>the</strong> Patía west to <strong>the</strong> Pacific.<br />

And only some 75 kilometers to <strong>the</strong> north a fourth major<br />

river, <strong>the</strong> Cauca, is born on <strong>the</strong> Páramo <strong>de</strong>l Buey, on <strong>the</strong> upper<br />

slopes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Puracé Volcano near <strong>the</strong> Huila-Cauca bor<strong>de</strong>r. This<br />

river runs <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> flanks <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cordillera Central toward <strong>the</strong><br />

north-east, and <strong>the</strong>n assumes <strong>the</strong> northbound course it will<br />

maintain for 1000 kilometers before joining its waters with <strong>the</strong><br />

Caribbean-bound Magdalena. These two rivers, forming one river-<br />

system, constitute <strong>the</strong> single major watercourse in <strong>the</strong> country.<br />

The Macizo Colombiano is <strong>the</strong> hub and central spoke <strong>of</strong> this<br />

web <strong>of</strong> rivers which spirals outward immense distances toward <strong>the</strong><br />

eastern, nor<strong>the</strong>rn and western quarters, and <strong>the</strong> consequences <strong>of</strong><br />

this web in terms <strong>of</strong> interregional and inter-pueblo

communication must always have been very important: <strong>the</strong> river-<br />

valleys were in a sense a series <strong>of</strong> highways leading outward<br />

from <strong>the</strong> massif and its peoples. And <strong>the</strong> rivers were only <strong>the</strong><br />

beginning, as we can appreciate from an attentive reading <strong>of</strong><br />

pertinent early documents which speak <strong>of</strong> ancient roads re-opened<br />

in post-conquest times. In o<strong>the</strong>r sections <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> An<strong>de</strong>s <strong>the</strong><br />

cordillera may have been an effective barrier to travel and<br />

communication; in <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> Colombia’s Macizo, <strong>the</strong> opposite<br />

was true. In precolumbian times <strong>the</strong> páramos that ring and crown<br />

<strong>the</strong> Macizo functioned as crossroads, as <strong>the</strong> pathways <strong>of</strong><br />

communication. Precisely because <strong>the</strong>y are not snowbound wastes,<br />

but ra<strong>the</strong>r are relatively flat plains whose low, stunted<br />

vegetation in <strong>the</strong>se equatorial latitu<strong>de</strong>s, however wild and lush,<br />

approaches open land, <strong>the</strong> páramos have been not <strong>the</strong> home, but<br />

ra<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> highway, for innumerable prehistoric peoples.<br />

“Today <strong>the</strong> Massif is a wild, solitary mountain country,<br />

remote and inhospitable, sparsely inhabited…..But it was not so<br />

in ancient times. Long before <strong>the</strong> arrival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> spaniards,<br />

generations <strong>of</strong> aboriginal peoples had occupied <strong>the</strong>se mountain-<br />

folds…..” i writes Reichel-Dolmat<strong>of</strong>f. The road which from <strong>San</strong><br />

Agustín ascends <strong>the</strong> uppermost courses <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Magdalena River<br />

through <strong>the</strong> village <strong>of</strong> Quinchana and on up to <strong>the</strong> river’s<br />

birthplace lakes was certainly an important one in ancient<br />

times; <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>scent from <strong>the</strong> Páramo <strong>de</strong> las Papas, down <strong>the</strong> far<br />

(eastern) si<strong>de</strong>, brings today’s traveler to <strong>the</strong> town <strong>of</strong> Valencia<br />

and <strong>the</strong>n on down to <strong>the</strong> city <strong>of</strong> Popayán, capital <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>de</strong>partamento <strong>of</strong> Cauca. Once up on <strong>the</strong> páramo, however, <strong>the</strong><br />

traveler is in a position to <strong>de</strong>scend <strong>the</strong> Cauca si<strong>de</strong> not only<br />

toward <strong>the</strong> northwest and Popayán, but as well toward <strong>the</strong><br />

southwest, across <strong>the</strong> Páramo <strong>de</strong>l Letrero and <strong>the</strong>n down to <strong>the</strong>

town <strong>of</strong> Almaguer, <strong>the</strong>re joining <strong>the</strong> road heading south to Pasto,<br />

capital <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> state <strong>of</strong> Nariño, which puts one on <strong>the</strong> high road—<br />

both in ancient times, and on today’s Panamerican Highway—to <strong>the</strong><br />

south, towards Ecuador.<br />

Leaving <strong>the</strong> meseta <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín not in ascent toward <strong>the</strong><br />

páramo upriver to <strong>the</strong> west, but ra<strong>the</strong>r downriver into <strong>the</strong> valley<br />

and <strong>the</strong>n on towards <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>ast, <strong>the</strong> traveler leaving <strong>the</strong><br />

Macizo will find <strong>the</strong> lowest pass in <strong>the</strong> eastern cordillera<br />

leading across to Mocoa and <strong>the</strong> headwaters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Putumayo and<br />

Caquetá Rivers. The Franciscan friar who gives us our first<br />

historical glimpse <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stone statues <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>,<br />

in 1756, reached <strong>San</strong> Agustín by this road, up from <strong>the</strong> Putumayo<br />

lowlands.<br />

There is, in addition, ano<strong>the</strong>r way to cross <strong>the</strong> Macizo<br />

between <strong>San</strong> Agustín on <strong>the</strong> eastern slopes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cordillera<br />

Central and Popayán in Cauca, by a road certainly in use since<br />

pre-columbian times, whose terminus lies close to <strong>San</strong> Agustín,<br />

on <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn si<strong>de</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Magdalena River in <strong>the</strong> municipality<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> José <strong>de</strong> Isnos. This road leaves Popayán up across <strong>the</strong><br />

southwestern flanks <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Puracé Volcano, crosses near <strong>the</strong><br />

Páramo <strong>de</strong>l Buey, and <strong>de</strong>scends <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>ep cleft <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mazamorras<br />

River down into <strong>San</strong> José. The first spanish conquistador to<br />

enter Colombia from <strong>the</strong> south, Sebastián <strong>de</strong> Belalcázar, probably<br />

ma<strong>de</strong> use <strong>of</strong> this road in 1538, and <strong>the</strong> men riding in his<br />

vanguard became <strong>the</strong> first europeans to travel through <strong>the</strong> valley<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín, and <strong>the</strong> first to cross <strong>the</strong> Macizo and <strong>the</strong> lands<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>.<br />

The area <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo Colombiano is today shared by three<br />

different states or <strong>de</strong>partamentos. That <strong>of</strong> Huila composes <strong>the</strong><br />

nor<strong>the</strong>astern si<strong>de</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo, and inclu<strong>de</strong>s <strong>the</strong> principal and

est-known sites <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> near <strong>the</strong> town <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong><br />

Agustín, up on <strong>the</strong> eastern flank <strong>the</strong> mountainous Knot. The<br />

northwestern and western si<strong>de</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo form part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

state <strong>of</strong> Cauca, and this state as well runs across <strong>the</strong> top <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> massif and down <strong>the</strong> eastern si<strong>de</strong>, so that <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>astern<br />

section <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> An<strong>de</strong>an Knot is also in <strong>the</strong> state <strong>of</strong> Cauca. The<br />

sou<strong>the</strong>rn and southwest slopes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo are inclu<strong>de</strong>d within<br />

<strong>the</strong> boundaries <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> state <strong>of</strong> Nariño, whose sou<strong>the</strong>rn edge runs<br />

along <strong>the</strong> bor<strong>de</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> nation <strong>of</strong> Ecuador. Evi<strong>de</strong>nce <strong>of</strong><br />

enclaves and vestiges <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancient Sculpting People are found<br />

in all three states.<br />

The Cordillera Central at its sou<strong>the</strong>rn extremity, before<br />

joining <strong>the</strong> Macizo, forms <strong>the</strong> irregular bor<strong>de</strong>r between Huila and<br />

Cauca with its chain <strong>of</strong> water-soaked páramos. If we except <strong>the</strong><br />

statues from a handful <strong>of</strong> very little-known sites south <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Macizo in <strong>the</strong> state <strong>of</strong> Nariño, and those from <strong>the</strong> few sites we<br />

know in <strong>the</strong> Popayán area to <strong>the</strong> west <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo in Cauca<br />

state—and <strong>the</strong>se two statue-areas are certainly those which most<br />

diverge stylistically from what we might call <strong>the</strong> ‘norm’—we<br />

could <strong>the</strong>n say that all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> presently-known sites <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> are found in this area comprising <strong>the</strong> two si<strong>de</strong>s<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cordillera Central as it approaches and joins <strong>the</strong> Macizo.<br />

The different <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> nuclei, though wi<strong>de</strong>ly<br />

separated in distance among <strong>the</strong> folds <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Macizo, are all<br />

much alike in terms <strong>of</strong> environment, and this similarity—<strong>the</strong> fact<br />

that <strong>the</strong>se different statue-making peoples lived in such<br />

strikingly similar locations—helps us to see <strong>the</strong>m, in a certain<br />

way, as a unit. The ‘alternative’ areas—as opposed to <strong>the</strong><br />

valley <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín—may have been colonies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> center, or<br />

unrelated co-religionists, or blood-related groups, or unrelated

political allies, or something quite different from all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

above. But all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> centers are found in <strong>the</strong><br />

zone between 1500 and 2000 meters in altitu<strong>de</strong> above sea level,<br />

with temperature in <strong>the</strong> 18-to-20 <strong>de</strong>gree centigra<strong>de</strong> range; <strong>the</strong><br />

rainfall is “abundant but intermittent,” <strong>the</strong>re is a wealth <strong>of</strong><br />

creeks, rivers and water in general, and <strong>the</strong> clothing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

land is verdant and vibrant. The soil is fertile though perhaps<br />

not exceptional: <strong>the</strong> black cap <strong>of</strong> humus above sterile red clay<br />

is usually less than 50 cm. <strong>de</strong>ep, but combined with <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>rwise positive environmental factors and <strong>the</strong> warm and<br />

mo<strong>de</strong>rate equatorial climate, <strong>the</strong> land produces thick tropical<br />

vegetation.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r characteristic which unites <strong>the</strong> different <strong>Pueblo</strong><br />

<strong>Escultor</strong> zones, and which helps to explain why <strong>the</strong>se lands would<br />

have been settled and populated, is this: <strong>the</strong>se middle-altitu<strong>de</strong><br />

zones are all very close to, and have easy access to, both <strong>the</strong><br />

higher-altitu<strong>de</strong> areas toward <strong>the</strong> páramos, and <strong>the</strong> lower, hotter<br />

regions downriver in <strong>the</strong> valleys. This easy access to vertical<br />

cultivation and vertical exploitation must have been a great<br />

factor in <strong>the</strong> lives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancient people and <strong>the</strong>ir economy, in<br />

many ways: different foodstuffs and o<strong>the</strong>r materials, different<br />

types <strong>of</strong> wood, fish, fruits, medicinal plants, different<br />

elements to work and construct and make tools with, and so on,<br />

are found in each altitu<strong>de</strong> zone, and many <strong>of</strong> those up above and<br />

down below are not produced in <strong>the</strong> central-altitu<strong>de</strong> zone. In<br />

addition, simply as example, <strong>the</strong> pineapples from <strong>the</strong> hot lower<br />

valleys are different in quality from those in <strong>the</strong> mid-levels,<br />

<strong>the</strong> cane and wood used to build with or <strong>the</strong> thatch to ro<strong>of</strong> with<br />

will always differ in use <strong>de</strong>pending on <strong>the</strong> production-zone, <strong>the</strong><br />

honey from each zone will differ because <strong>the</strong> wild-flowers will

e distinct, and so on, and <strong>the</strong>se types <strong>of</strong> values will always be<br />

factors in <strong>the</strong> use that people have for <strong>the</strong>ir products.<br />

With few exceptions <strong>the</strong> statues and o<strong>the</strong>r material vestiges<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancient sculptors are only found in <strong>the</strong>se analogous<br />

pockets in <strong>the</strong> mountains, with altitu<strong>de</strong>s and landforms and<br />

environmental conditions that vary but little. When one is in<br />

<strong>the</strong> statue-areas, this fact can be surprising, because <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

altitu<strong>de</strong> zones are so close. Both <strong>the</strong> upper zones, and <strong>the</strong><br />

regions down-river below, are <strong>of</strong>ten but a few hours walk away,<br />

and visible, and yet in those o<strong>the</strong>r altitu<strong>de</strong>-zones <strong>the</strong>re is no<br />

evi<strong>de</strong>nce <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> villages, statues, ceramics, tombs and<br />

earthworks <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancient stone-sculpting people.<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong><br />

The first-known and principal sites <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>,<br />

ranged about <strong>the</strong> town <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín, are located in an isolated<br />

valley near <strong>the</strong> headwaters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Magdalena River on <strong>the</strong> eastern<br />

si<strong>de</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cordillera Central. <strong>San</strong> Agustín’s valley is unique<br />

among <strong>the</strong> mid-level zones inhabited by <strong>the</strong> ancient sculptors in<br />

<strong>the</strong> sense that it is very large, some 1300 square kilometers in<br />

size—<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r statue-areas are relatively small pockets <strong>of</strong><br />

valley—and thus allowed for <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>velopment <strong>of</strong> a much larger<br />

center than would or could <strong>de</strong>velop elsewhere. As <strong>the</strong> Magdalena<br />

rushes from <strong>the</strong> páramo down <strong>the</strong> steep mountain heights heading<br />

east, it comes quite sud<strong>de</strong>nly to this plateau-like meseta or<br />

valley, 1700-to-1800 meters above sea level, triangular in<br />

shape, and while not flat, yet less precipitous than in <strong>the</strong><br />

upper course <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> river. <strong>San</strong> Agustín’s valley, embracing all

<strong>the</strong> main statue sites, is an intermediate step in <strong>the</strong> river’s<br />

<strong>de</strong>scent to <strong>the</strong> main valley floor, and just as it arrives<br />

coursing <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> Macizo slopes to <strong>the</strong> valley <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> statues, so<br />

at <strong>the</strong> western edge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> irregular triangle <strong>the</strong> river once<br />

again drops <strong>of</strong>f steeply and wildly, and continues westward<br />

toward <strong>the</strong> valley below. The meseta is cut in half by <strong>the</strong> <strong>de</strong>ep<br />

canyon <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> turbulent river rushing from northwest to<br />

sou<strong>the</strong>ast, with <strong>the</strong> town <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín on <strong>the</strong> southwest si<strong>de</strong><br />

and <strong>the</strong> town <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> José <strong>de</strong> Isnos on <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>ast.<br />

A handful <strong>of</strong> numbers will help us appreciate <strong>the</strong> extent to<br />

which <strong>the</strong> lithic works in <strong>the</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín statue-area<br />

predominate in <strong>the</strong> study <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> monuments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong><br />

<strong>Escultor</strong>. The present survey inclu<strong>de</strong>s some 460 total statues<br />

from all <strong>the</strong> statue-areas. About 310 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se are from <strong>the</strong><br />

valley <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín, which makes for some 67% or 2/3 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

total. However, as mentioned, <strong>the</strong> statues from <strong>the</strong> Nariño zone<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Popayán zone can be grouped as <strong>of</strong>ten rougher and/or less<br />

nuanced than <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs, and <strong>the</strong>se two areas are in addition <strong>the</strong><br />

two most distant statue-areas from <strong>the</strong> ‘core’ valley. If we<br />

take away <strong>the</strong> 31 pieces in <strong>the</strong> present study which were found in<br />

those two areas—and such a judgment may well be a valid one—we<br />

<strong>the</strong>n have a total <strong>of</strong> some 310 <strong>San</strong> Agustín-area statues out <strong>of</strong> a<br />

total <strong>of</strong> 426, and <strong>the</strong> percentage in <strong>the</strong> core area <strong>the</strong>n jumps to<br />

73%, very close to ¾ <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> total. These stone sculptures in<br />

<strong>the</strong> valley <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín have been found in perhaps 50 separate<br />

sites—without mentioning <strong>the</strong> innumerable tomb-sites and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

ancient vestiges which did not produce statues—and are located<br />

on both si<strong>de</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Magdalena river, in <strong>the</strong> lands <strong>of</strong> both<br />

municipalities.

Past <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn edge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín zone ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

river, <strong>the</strong> Bordones, flows down from <strong>the</strong> cordillera heights,<br />

eventually to join <strong>the</strong> Magdalena. Before this union, <strong>the</strong><br />

Bordones is augmented by <strong>the</strong> waters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Granates River at an<br />

altitu<strong>de</strong> commensurate with those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> various o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Pueblo</strong><br />

<strong>Escultor</strong> areas. Near <strong>the</strong> banks <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Granates is <strong>the</strong> statue<br />

site called Morelia, which is also known as Saladoblanco,<br />

although this latter name more correctly is that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> small<br />

town nearby, some 10 kilometers to <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>ast <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> statue<br />

site and north <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bordones, nearer to <strong>the</strong> Magdalena. At<br />

least one o<strong>the</strong>r statue site is known nearby; <strong>the</strong> Saladoblanco<br />

area is about 25 kilometers to <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>ast <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín.<br />

Some 7 statues in <strong>the</strong> present survey were discovered in this<br />

zone.<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> centers are located fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

north, in <strong>the</strong> foothills <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eastern slopes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cordillera<br />

Central; <strong>the</strong> waters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se sites all flow down to join <strong>the</strong><br />

Magdalena. Two river-systems in particular are key. One is<br />

that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> La Plata River which is born from <strong>the</strong> conjunction <strong>of</strong><br />

a number <strong>of</strong> upper-course rivers <strong>de</strong>scending from <strong>the</strong> slopes <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Puracé Volcano, atop <strong>the</strong> cordillera and astri<strong>de</strong> <strong>the</strong> Huila-<br />

Cauca bor<strong>de</strong>r. The La Plata River valley contains several<br />

important sites <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>, located some 50 or 60<br />

kilometers from <strong>San</strong> Agustín toward <strong>the</strong> north and nor<strong>the</strong>ast. The<br />

Páez River, flowing south <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> slopes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Páramo <strong>de</strong> <strong>San</strong>to<br />

Domingo on <strong>the</strong> western edge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nevado (or Snow-Peak) <strong>de</strong>l<br />

Huila, turns eastward and <strong>the</strong>n meets <strong>the</strong> La Plata River very<br />

near <strong>the</strong> town <strong>of</strong> La Plata; <strong>the</strong> united river, carrying <strong>the</strong> name<br />

<strong>of</strong> Páez, <strong>the</strong>n continues toward <strong>the</strong> east and eventually issues<br />

into <strong>the</strong> Magdalena in <strong>the</strong> main valley below. In <strong>the</strong> valley <strong>of</strong>

<strong>the</strong> Páez, too, statues and o<strong>the</strong>r traces <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong><br />

are evi<strong>de</strong>nt in quantity.<br />

The La Plata valley sites <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> have yet<br />

to be a<strong>de</strong>quately studied, but at least three important statue<br />

areas have been i<strong>de</strong>ntified. The westernmost <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> three, known<br />

as Moscopán, inclu<strong>de</strong>s a number <strong>of</strong> different sites on <strong>the</strong> banks<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bedón or Aguacatal River as it <strong>de</strong>scends toward <strong>the</strong> La<br />

Plata. This series <strong>of</strong> sites is relatively close to <strong>the</strong> present-<br />

day town <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong>ta Leticia, and while <strong>the</strong> town is in a slightly<br />

higher zone, closer to <strong>the</strong> conditions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> páramo, <strong>the</strong> various<br />

statue-sites are well below <strong>the</strong> town, down un<strong>de</strong>r <strong>the</strong> canyon<br />

walls and located in small vegas or pockets by <strong>the</strong> shores <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

dark, wildly rushing river, where ecological and climatological<br />

conditions are closer to those in <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r statue areas. At<br />

least 25 statues have been reported from <strong>the</strong> Moscopán sites, <strong>of</strong><br />

which 20 were available for inclusion in <strong>the</strong> present survey.<br />

Not far to <strong>the</strong> north <strong>of</strong> Moscopán and still on <strong>the</strong> western<br />

or cordillera si<strong>de</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> La Plata River is ano<strong>the</strong>r nucleus <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>, located on <strong>the</strong> banks <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Moscopán River<br />

before its union with <strong>the</strong> La Plata. In 1918 this site, known as<br />

Aguabonita, became <strong>the</strong> first ‘alternative’ statue-area—that is,<br />

outsi<strong>de</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>San</strong> Agustín valley—to be <strong>de</strong>tailed in print; since<br />

that time, however, very little investigative work has been<br />

carried out, and virtually nothing published on this ancient<br />

site. There are only four statues to be seen at Aguabonita, but<br />

in addition to <strong>the</strong> obvious similarities in style and iconography<br />

that link <strong>the</strong>se statues to <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong> work, <strong>the</strong><br />

location once again shares altitu<strong>de</strong> and environmental conditions<br />

with <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r statue areas.

The third statue nucleus in <strong>the</strong> La Plata valley, named<br />

Platavieja and located in <strong>the</strong> vicinity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> town <strong>of</strong> La<br />

Argentina, Huila, is on <strong>the</strong> eastern si<strong>de</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> river—still<br />

known <strong>the</strong>re as <strong>the</strong> Loro, but very soon to become <strong>the</strong> La Plata—<br />

and slightly to <strong>the</strong> south <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Moscopán and Aguabonita areas.<br />

Platavieja lies some 40 kilometers or so nor<strong>the</strong>ast <strong>of</strong> <strong>San</strong><br />

Agustín, which puts it only some 20 kilometers or so north <strong>of</strong><br />

Saladoblanco and Oporapa (a nearby petroglyph site), separated<br />

from <strong>the</strong>se two centers <strong>of</strong> lithic sculpture by a single narrow<br />

branch running <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> main cordillera, known as <strong>the</strong> Cuchilla <strong>de</strong><br />

las Minas. Platavieja, so-named because it was <strong>the</strong> original<br />

seat in <strong>the</strong> 1600’s <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> town <strong>of</strong> La Plata, was in a position<br />

for easy communication both with Moscopán area not far away to<br />

<strong>the</strong> northwest and with <strong>the</strong> Saladoblanco area (en route to <strong>San</strong><br />

Agustín’s valley) over this single, thickly jungle-covered range<br />

to <strong>the</strong> south. Some 20 statues may be seen today in <strong>the</strong><br />

Platavieja region, in addition to a good number <strong>of</strong> petroglyph<br />

<strong>de</strong>signs carved on large live-rock boul<strong>de</strong>rs.<br />

The o<strong>the</strong>r important river in this part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong><br />

<strong>Escultor</strong> region, <strong>the</strong> Páez, rolls down from <strong>the</strong> slopes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Nevado <strong>de</strong>l Huila and continues on north-to-south, traversing<br />

nearly <strong>the</strong> entire territory <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Páez Indians before joining<br />

waters with <strong>the</strong> La Plata River not far from its eventual<br />

juncture with <strong>the</strong> Madgalena. Within <strong>the</strong> extensive Páez lands a<br />

good number <strong>of</strong> sites—probably at least a score—have produced<br />

statues and o<strong>the</strong>r remains <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pueblo</strong> <strong>Escultor</strong>, <strong>the</strong> principal<br />

such group <strong>of</strong> sites near <strong>the</strong> Páez Indian al<strong>de</strong>a (or village) <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>San</strong> Andrés <strong>de</strong> Pisimbalá having taken to itself <strong>the</strong> name <strong>of</strong><br />

Tierra<strong>de</strong>ntro. Almost 80 statues from Tierra<strong>de</strong>ntro have, over<br />

<strong>the</strong> years, been published, and 67 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m appear in this survey;

<strong>the</strong> area is some 80 kilometers from <strong>San</strong> Agustín toward <strong>the</strong><br />

nor<strong>the</strong>ast.<br />

Many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> total <strong>of</strong> Tierra<strong>de</strong>ntro statues were found in a<br />