Download the full program as PDF - Fashion Film Festival

Download the full program as PDF - Fashion Film Festival

Download the full program as PDF - Fashion Film Festival

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

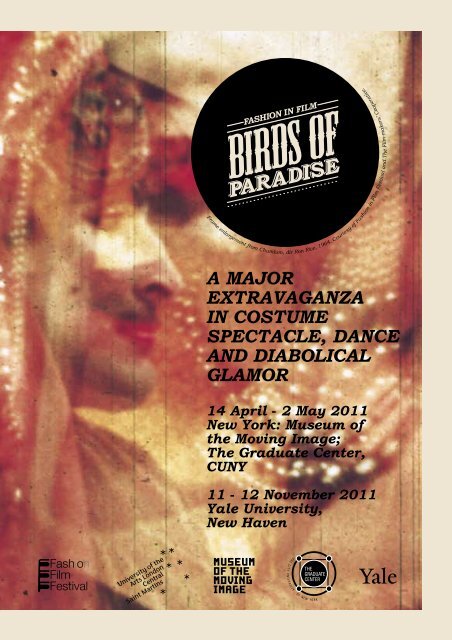

A mAjor<br />

extrAvAgAnzA<br />

in costume<br />

spectAcle, DAnce<br />

AnD DiAbolicAl<br />

glAmor<br />

14 April - 2 may 2011<br />

new York: museum of<br />

<strong>the</strong> moving image;<br />

<strong>the</strong> graduate center,<br />

cunY<br />

11 - 12 november 2011<br />

Yale university,<br />

new Haven

The F<strong>as</strong>hion in <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Festival</strong> is proud to present a<br />

special edition of birds of paradise, an intoxicating<br />

exploration of costume <strong>as</strong> a form of cinematic spectacle<br />

throughout European and American cinema. The<br />

<strong>program</strong> highlights those episodes in cinema history<br />

which most distinctly foreground costume, adornment,<br />

and styling <strong>as</strong> vehicles of sensuous ple<strong>as</strong>ure and<br />

enchantment. Underground films by Kenneth Anger,<br />

Jack Smith, Jose Rodriguez-Soltero, Steven Arnold,<br />

and James Bidgood constitute one such episode.<br />

Their exquisitely decadent, highly stylized visions <strong>full</strong><br />

of lyrical f<strong>as</strong>cination with jewelry, textures, layers,<br />

luxurious fabrics, and make-up unlock <strong>the</strong> opulence of<br />

earlier periods of popular cinema, especially “spectacle”<br />

and Orientalist films of <strong>the</strong> 1920s; early dance, trick<br />

films and féeries of <strong>the</strong> 1890s and 1900s; and Hollywood<br />

exotica of <strong>the</strong> 1930s and 1940s.<br />

The <strong>program</strong> forges a link between <strong>the</strong> characteristic<br />

visual intensity of American underground cinema<br />

and <strong>the</strong> dreamlike, marvelous world of silent cinema.<br />

In <strong>the</strong>ir magical and sometimes phant<strong>as</strong>magorical<br />

tableaux, costume and artifice are not merely on display.<br />

Instead, <strong>the</strong>y dazzle, seduce, surprise, or dramatically<br />

metamorphose—<strong>the</strong>y become a type of special effect.<br />

birds of paradise delves into <strong>the</strong> archives to show<br />

that costume and adornment have often been a key<br />

component in film and have, from early on, proved<br />

absolutely vital in showc<strong>as</strong>ing such b<strong>as</strong>ic properties <strong>as</strong><br />

movement, change, light and, of course, color. Stressing<br />

<strong>the</strong> aes<strong>the</strong>tic <strong>as</strong>pects of cinema, <strong>the</strong> <strong>program</strong> suggests<br />

one way of closing <strong>the</strong> cleavage (or at le<strong>as</strong>t temporarily<br />

suspending <strong>the</strong> opposition) between avant-garde film<br />

and mainstream commercial cinema. This is very much<br />

in <strong>the</strong> spirit of such progressive journals <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> pre-war<br />

French cinéa-ciné pour tous and <strong>the</strong> post-war American<br />

<strong>Film</strong> culture, and of course, <strong>the</strong> very attitude of <strong>the</strong><br />

experimental filmmakers featured.<br />

The festival presents many rare screenings including Nino<br />

Oxilia’s rapsodia satanica (1915/1917), a newly restored<br />

print of Jack Smith’s normal love (1963), Jose Rodriguez-<br />

Soltero’s lupe (1966), and Alexandre Volkoff’s secrets<br />

of <strong>the</strong> e<strong>as</strong>t (1928). There will also be favourites such <strong>as</strong><br />

Cecil B. DeMille’s male and Female (1919), Erich von<br />

Stroheim’s <strong>the</strong> merry Widow (1925), <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> talks, film<br />

introductions and seminars. The festival takes place at<br />

Museum of <strong>the</strong> Moving Image and The Graduate Center,<br />

CUNY this April and May, followed by a symposium with<br />

screenings at Yale University in November.<br />

All silent films will be accompanied with live music by Donald Sosin,<br />

Stephen Horne or Makia Matsumura.<br />

“The F<strong>as</strong>hion in <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Festival</strong> h<strong>as</strong> established itself <strong>as</strong> a lively and<br />

wonder<strong>full</strong>y <strong>program</strong>med cinema event that spans a wide range of<br />

genres and periods, finding a common link in <strong>the</strong> medium’s emph<strong>as</strong>is<br />

on visual spectacle, dazzling excess, and general enchantment.<br />

Museum of <strong>the</strong> Moving Image is thrilled to be <strong>the</strong> New York venue for<br />

this original and essential film festival.”<br />

David Schwartz, Chief Curator, Museum of <strong>the</strong> Moving Image<br />

Founded in 2005, F<strong>as</strong>hion in <strong>Film</strong> is<br />

an exhibition, research and education<br />

project b<strong>as</strong>ed at Central Saint Martins<br />

College of Art and Design. Birds<br />

of Paradise is a second collaboration<br />

with Museum of <strong>the</strong> Moving Image,<br />

and is organized in partnership with<br />

<strong>Film</strong> Studies Program and <strong>Film</strong>s at <strong>the</strong><br />

Whitney at Yale University, The Center<br />

for <strong>the</strong> Humanities and The Graduate<br />

Center at City University of New York.<br />

The <strong>program</strong> is curated by Marketa<br />

Uhlirova, with Ronald Gregg, Stuart<br />

Comer, Eugenia Paulicelli, and Inga<br />

Fr<strong>as</strong>er. It is organized for Moving Image<br />

by David Schwartz.<br />

<strong>Festival</strong> advisors: Serge Bromberg,<br />

Alistair O’Neill, Eric de Kuyper, Ronny<br />

Temme, Christel Tsilibaris, Marc Siegel.

MUSEUM OF THE MOVING IMAGE<br />

FriDAY, April 15<br />

7:00pm<br />

underground opulence<br />

Bursting with color, this <strong>program</strong><br />

reconnects <strong>the</strong> avant-garde queer<br />

sensibility of underground film not<br />

with its literal inspirations (Hollywood<br />

icons such <strong>as</strong> Alla Nazimova, Marlene<br />

Dietrich, or Maria Montez) but ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

with some genres in early film which—<br />

with <strong>the</strong>ir ornamental costumes<br />

and décor—anticipate some of <strong>the</strong><br />

richness of <strong>the</strong> underground’s camp<br />

aes<strong>the</strong>ticism.<br />

Total running time: 130 mins.<br />

Introduced by David Schwartz and<br />

Marketa Uhlirova<br />

Live music by Makia Matsumura<br />

tit for tat<br />

(la peine du talion)<br />

Dir. G<strong>as</strong>ton Velle, Pathé Frères,<br />

1906, France<br />

Gloriously winged insects seek revenge<br />

for <strong>the</strong> injustices brought about by <strong>the</strong><br />

popular practice of lepidoptery: <strong>the</strong><br />

catching of butterflies and moths for<br />

<strong>the</strong> purpose of scientific observation.<br />

Velle’s richly colored film is one of <strong>the</strong><br />

finest examples of its kind.<br />

metempsychosis (métempsycose)<br />

Dir. Segundo de Chomón, Pathé Frères,<br />

1907, France<br />

The special effects pioneer Segundo de<br />

Chomón reinterprets for <strong>the</strong> camera<br />

a famous stage illusion that featured<br />

a metamorphosis from one object (or<br />

person) into ano<strong>the</strong>r. A statue turns into<br />

a butterfly fairy who performs a number<br />

of ravishing costume transformations.<br />

Frame enlargement from Tit for Tat, dir G<strong>as</strong>ton Velle, 1906. Courtesy of Lobster <strong>Film</strong>s.<br />

puce moment<br />

Dir. Kenneth Anger, with Yvonne<br />

Marquis, 1949<br />

Costumes from Kenneth Anger’s<br />

collection<br />

Puce Moment is a fragment filmed<br />

in 1949 and later edited by Anger<br />

himself into a stand-alone piece. It w<strong>as</strong><br />

conceived <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> feature-length film<br />

Puce Women, and w<strong>as</strong> to be Anger’s<br />

tribute to <strong>the</strong> mythological Hollywood<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Jazz Age and <strong>the</strong> perversely<br />

luxurious t<strong>as</strong>tes and lifestyles of<br />

female sirens such <strong>as</strong> Mae Murray,<br />

Barbara La Marr, Marion Davies, and<br />

Gloria Swanson (some of whom are<br />

described in his exposé Hollywood<br />

Babylon). Referring to <strong>the</strong> purplegreen<br />

iridescent color of 1920s flapper<br />

gowns, Anger’s mood sketch evokes<br />

<strong>the</strong> archetypal moment of a film star’s<br />

dressing up. It is a dizzying parade of<br />

vintage gowns: <strong>the</strong>ir beading, sequins<br />

and embroidery shimmer aggressively<br />

in front of <strong>the</strong> camera, taking up entire<br />

film frames.<br />

<strong>the</strong> pearl Fisher<br />

(le pêcheur de perles)<br />

Dir. Ferdinand Zecca, Pathé Frères,<br />

1907, France<br />

A deep-sea diver encounters strange<br />

and marvelous creatures in an<br />

underwater kingdom. The final<br />

apo<strong>the</strong>osis bo<strong>as</strong>ts remarkable sets<br />

Frame enlargement from The Pearl Fisher, dir<br />

Ferdinand Zecca, 1907. Courtesy of Lobster <strong>Film</strong>s.<br />

festooned with strings of pearls that<br />

recall Méliès’s Orientalist décors for<br />

The Palace of Arabian Nights (1905).<br />

normal love<br />

Dir. Jack Smith, 1963<br />

With Diana Baccus, Mario Montez,<br />

Beverly Grant<br />

Costumes by Jack Smith and actors<br />

Print courtesy of Gladstone Gallery,<br />

New York<br />

Jack Smith, Untitled, c.1958-1962 (photograph from <strong>the</strong> set of Normal<br />

Love, dir Jack Smith, 1963). © Estate of Jack Smith. Courtesy of<br />

Gladstone Gallery, New York.<br />

After completing Flaming Creatures,<br />

Smith shot <strong>the</strong> more ambitious Normal<br />

Love in dazzling color, with elaborate<br />

sets (including a Busby Berkeleyesque<br />

multi-tiered cake made by Claes<br />

Oldenburg), and costumes inspired by<br />

horror films and Maria Montez epics.<br />

Smith c<strong>as</strong>t poets, artists, and actors<br />

from <strong>the</strong> New York underground scene,<br />

including Mario Montez <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mermaid,<br />

Beverly Grant <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cobra Woman, plus<br />

Andy Warhol and a very pregnant Beat<br />

poet Diane di Prima <strong>as</strong> chorus dancers<br />

on Oldenburg’s cake. Smith never<br />

finished editing a definitive version of<br />

<strong>the</strong> film, but what remains wonder<strong>full</strong>y<br />

illustrates his visionary appropriation of<br />

Hollywood sensuality and excess.

MUSEUM OF THE MOVING IMAGE<br />

sAturDAY, April 16<br />

2:00pm<br />

secrets of <strong>the</strong> e<strong>as</strong>t<br />

(geheimnisse des orients /<br />

shéhérazade)<br />

Dir. Alexandre Volkoff, 1928, Germany/<br />

France, 126 mins.<br />

With Marcella Albani, D. Dmitriev,<br />

Brigitte Helm<br />

Costume design by Boris Bilinsky and<br />

sets by Ivan Lochakoff<br />

Live music by Stephen Horne<br />

Print courtesy of National <strong>Film</strong> Center<br />

Tokyo<br />

A big-budget Franco-German coproduction,<br />

Volkoff’s “Luxusfilm of<br />

<strong>the</strong> year” is an exquisite fant<strong>as</strong>y of an<br />

escape into <strong>the</strong> “Orient.” The appetite<br />

for anything Oriental, galvanised some<br />

twenty years before by <strong>the</strong> Ballets<br />

Russes and f<strong>as</strong>hion designer Paul<br />

Poiret, w<strong>as</strong> still going strong in both<br />

European and Hollywood cinema<br />

toward <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> silent era. Secrets<br />

of <strong>the</strong> E<strong>as</strong>t showc<strong>as</strong>es some remarkable<br />

artistry by two Russian émigrés: <strong>the</strong><br />

ornamental sets by Ivan Lochakoff and<br />

sensuous costumes by Boris Bilinsky<br />

were designed in a magnificent blend<br />

of E<strong>as</strong>tern and Western motifs, from<br />

stylised Islamic and far-e<strong>as</strong>tern<br />

influences to Art Nouveau, Art Deco,<br />

and Expressionism. With its paradise<br />

atmosphere and a sumptuous<br />

stencil-colored sequence, <strong>the</strong> film is<br />

a fairy-tale world of fancy filled with<br />

adventure, magic, mystery and harem<br />

dancers.<br />

Secrets of <strong>the</strong> E<strong>as</strong>t, dir Alexandre Volkoff, 1928. Courtesy of Aurora Productions / The Kobal Collection.<br />

5:00pm<br />

male and Female<br />

Male and Female, dir Cecil B. DeMille, 1919.<br />

Courtesy of The Kobal Collection.<br />

Dir. Cecil B. Demille, 1919, 97 mins.<br />

With Gloria Swanson, Thom<strong>as</strong> Meighan<br />

Costume design by Clare West, Mitchell<br />

Leisen, Paul Iribe<br />

35mm print from George E<strong>as</strong>tman House<br />

International Museum of Photography<br />

and <strong>Film</strong><br />

Introduction by Inga Fr<strong>as</strong>er<br />

Accompanied by music from Stephen Horne<br />

DeMille typically inserted into his<br />

modern-day narratives exotic episodes,<br />

so-called “visions,” that provided<br />

seductive fant<strong>as</strong>y escape and featured<br />

climactic costuming. In Male and<br />

Female’s notorious dream sequence,<br />

Gloria Swanson dramatically enters<br />

into a lions’ den kitted out in a lavish<br />

all-white robe and headdress made of<br />

pearls, beads, and peacock fea<strong>the</strong>rs.<br />

The show-stopping outfit w<strong>as</strong> designed<br />

by Mitchell Leisen and w<strong>as</strong> reportedly<br />

so heavy that Swanson required <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>as</strong>sistance of two members of <strong>the</strong> crew<br />

to move around <strong>the</strong> set.<br />

7:00pm<br />

A Double bill on costume and<br />

excess (Dedicated to Kenneth<br />

Anger)<br />

“Because America is <strong>the</strong> Ple<strong>as</strong>ure Dome<br />

of <strong>the</strong> world... <strong>the</strong> materialistic dream<br />

is so strong that you have to be of <strong>the</strong><br />

purity of Parsifal to banish Klingsor’s<br />

c<strong>as</strong>tle... <strong>the</strong>re’ll always be a penalty to<br />

pay for <strong>the</strong>se artificial paradises.”<br />

Kenneth Anger<br />

inauguration of <strong>the</strong> ple<strong>as</strong>ure Dome<br />

Dir. Kenneth Anger, 1954/1966, 38 mins.<br />

With Samson De Brier, Marjorie Cameron,<br />

Joan Whitney, Anaïs Nin<br />

Costumes and sets by Kenneth Anger,<br />

Samson de Brier, and actors<br />

Anger’s Inauguration is a hedonistic<br />

costume extravaganza through and<br />

through. The idea for <strong>the</strong> film w<strong>as</strong> in<br />

fact born at a m<strong>as</strong>querade party Anger<br />

attended in 1953. Held at painter Renate<br />

Druks’s home, <strong>the</strong> soirée brought<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r a coterie of avant-garde<br />

actors, directors and poets (many of<br />

whom star in <strong>the</strong> film), all exquisitely<br />

costumed for <strong>the</strong> occ<strong>as</strong>ion. According<br />

to <strong>the</strong> writer Anaïs Nin, Anger himself<br />

came dressed “<strong>as</strong> Hectate, goddess of<br />

<strong>the</strong> moon, earth and infernal regions,<br />

sorcery and witchcraft. Only one heavily<br />

made-up eye w<strong>as</strong> visible. His long<br />

black fingernails were made of black<br />

quills. The rest w<strong>as</strong> all a towering<br />

figure of lace, veils, beads and fea<strong>the</strong>rs.”<br />

Anger transformed this experience<br />

into a hallucinatory cinematic vision,<br />

a ritual that is both enigmatic and<br />

idiosyncratic.<br />

Inauguration of <strong>the</strong> Ple<strong>as</strong>ure Dome, dir Kenneth Anger, 1954/1966.<br />

Courtesy of BFI.

MUSEUM OF THE MOVING IMAGE<br />

<strong>the</strong> Devil is a Woman<br />

Dir. Josef von Sternberg, 1935. 76 mins.<br />

With Marlene Dietrich, Cesar Romero,<br />

Lionel Atwill<br />

Costumes by Travis Banton, wardrobe<br />

by Henry West<br />

We invited Kenneth Anger to tell us<br />

which film we should <strong>program</strong> alongside<br />

his Inauguration of <strong>the</strong> Ple<strong>as</strong>ure Dome<br />

and he suggested “something by Travis<br />

Banton for von Sternberg or DeMille”.<br />

We took note. The Devil is a Woman,<br />

close to Anger’s own vision in Inauguration,<br />

makes m<strong>as</strong>querade its very leitmotif—from<br />

Marlene Dietrich’s inexorably<br />

made-up face to <strong>the</strong> near-grotesque<br />

disguises worn by revellers at Seville’s<br />

carnival during which this film is set.<br />

Dietrich’s uber-sensuous character<br />

Concha Perez enjoys a game of seduction<br />

while unapologetically flaunting<br />

Banton’s veils, outlandish headpieces,<br />

fans and fringes.<br />

sunDAY, April 17<br />

Frame enlargement from The Devil is a Woman, dir.<br />

Josef von Sternberg, 1935.<br />

2:00pm<br />

Dreams of Darkness and color<br />

This <strong>program</strong> explores <strong>the</strong> role of costume<br />

in several silent cinema journeys<br />

into darkness, all of which are executed<br />

in color.<br />

Total running time: c.80 mins.<br />

With an introduction by Eugenia Paulicelli.<br />

Live music by Stephen Horne<br />

<strong>the</strong> red spectre (le spectre rouge)<br />

Dir. Segundo de Chomón, Pathé Frères,<br />

1907, France<br />

Costumes and sets by Segundo de<br />

Chomón<br />

(Stencil-colored)<br />

In a dark cavern a devil-like magician<br />

performs a series of tricks putting to<br />

great use his magnificent cloak.<br />

<strong>the</strong> pillar of Fire (la Danse du feu)<br />

Dir. Georges Méliès, 1899, France<br />

With Jeanne d’Alcy<br />

Costumes and sets by Georges Méliès<br />

(Hand-colored)<br />

B<strong>as</strong>ed on H. Rider Haggard’s novel She,<br />

a demon conjures a woman wearing a<br />

voluminous white dress who performs a<br />

dance à la Loïe Fuller.<br />

The Butterflies (Le Farfalle)<br />

Dir. unknown, 1907, Italy<br />

(Tinted and hand-colored)<br />

Frame enlargement from The Red Spectre, dir.<br />

Segundo de Chomόn, 1907. Courtesy Lobster <strong>Film</strong>s.<br />

Geish<strong>as</strong> dance and play with a butterfly<br />

woman whom <strong>the</strong>y have imprisoned<br />

within a cage. Her lover comes to rescue<br />

her, only to find himself killed by<br />

<strong>the</strong> group. A butterfly revenge ensues.<br />

rapsodia satanica<br />

Dir. Nino Oxilia, 1915, Italy<br />

With Lyda Borelli, Andrea Habay, Ugo<br />

Bazzini<br />

Alba’s gowns by Mariano Fortuny<br />

(Tinted and stencil-colored)<br />

A prime example of <strong>the</strong> diva genre, Rapsodia<br />

Satanica is a m<strong>as</strong>terpiece of silent<br />

Italian cinema. It features Lyda Borelli<br />

<strong>as</strong> Alba d’Oltrevita in a Faustian tale of<br />

a woman’s search for eternal youth and<br />

worldly ple<strong>as</strong>ures. The most persistent<br />

<strong>the</strong>mes punctuating <strong>the</strong> film are Alba’s<br />

narcissism and her manipulation of<br />

a thin, diaphanous veil in scenes of<br />

seduction, reflection and melancholy.<br />

Sensuous, <strong>the</strong> veil may evoke <strong>the</strong> craze<br />

for exotic dances that swept European<br />

and American stage and screen around<br />

<strong>the</strong> turn of <strong>the</strong> century but in Alba’s<br />

hands it is more introspective and<br />

eerie than seductive. It <strong>as</strong>sumes a life<br />

of its own <strong>as</strong> it is moulded and layered<br />

over her face and body, producing an<br />

e<strong>the</strong>real, phant<strong>as</strong>mic effect made even<br />

more striking by <strong>the</strong> use of color. Alba’s<br />

nemesis, <strong>the</strong> omnipresent devil, also<br />

operates his vampire-style cloak to<br />

great effect.<br />

With grateful thanks to <strong>the</strong> Italian Cultural<br />

Institute who have supported this<br />

screening on <strong>the</strong> occ<strong>as</strong>ion of celebrating<br />

<strong>the</strong> 150th Anniversary of <strong>the</strong> unification<br />

of Italy.<br />

Frame enlargement from Rapsodia Satanica, dir. Nino Oxilia, 1915/1917. Courtesy EYE <strong>Film</strong> Institute Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands.

MUSEUM OF THE MOVING IMAGE<br />

4:30pm<br />

pink narcissus<br />

Dir. James Bidgood, 1971, 71 mins.<br />

With Bobby Kendall, Don Brooks<br />

Costume and set design by James Bidgood<br />

Pink Narcissus, dir James Bidgood, 1971. Courtesy of BFI.<br />

With a background in still photography<br />

and stage costume design, but no<br />

training in film whatsoever, Bidgood<br />

shot Pink Narcissus on <strong>the</strong> cheap in<br />

<strong>the</strong> confines of his bedroom, using<br />

Bolex camer<strong>as</strong> with 8mm Kodachrome<br />

and 16mm Ektachrome stock. It took<br />

over seven years to make and <strong>the</strong> result<br />

is an epic and bold work. A series<br />

of homoerotic fant<strong>as</strong>ies, <strong>the</strong> film’s<br />

singular aes<strong>the</strong>tic is at once highly<br />

camp and deliberately tr<strong>as</strong>hy, yet it<br />

is moving and stunningly beautiful.<br />

Its charming naiveté evokes early film<br />

pioneers such <strong>as</strong> Méliès or de Chomón;<br />

like <strong>the</strong>m, Bidgood w<strong>as</strong> heavily invested<br />

in fabricating his own elaborate<br />

sets and costumes, <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> his own<br />

universe of solutions and tricks. Sadly,<br />

<strong>the</strong> film w<strong>as</strong> not edited by <strong>the</strong> artist<br />

himself who had, by <strong>the</strong> early 1970s,<br />

lost creative control of his mesmerising<br />

footage.<br />

7:00pm<br />

Golden Butterfly (Der Goldene<br />

schmetterling)<br />

Dir. Michael Curtiz, 1926, Austria, 77 mins.<br />

With Lili Damita, Hermann Leffler<br />

35mm print from British <strong>Film</strong> Institute<br />

Live music by Stephen Horne.<br />

Golden Butterfly stars French actress<br />

Lili Damita, director Michael<br />

Curtiz’s <strong>the</strong>n-wife. Her film career w<strong>as</strong><br />

launched by a beauty contest, though<br />

she already had experience <strong>as</strong> a revue<br />

dancer on Parisian stages, performing<br />

under <strong>the</strong> pseudonym Lily Deslys. The<br />

story of Golden Butterfly epitomises <strong>the</strong><br />

familiar jazz-age conflict between female<br />

independence and morality where<br />

Damita’s dancer is portrayed <strong>as</strong> a moth<br />

driven to <strong>the</strong> glitter of <strong>the</strong> stage only<br />

to be burnt. Following <strong>the</strong> successful<br />

Red Heels, this w<strong>as</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r of Curtiz’s<br />

ambitious European co-productions<br />

set in <strong>the</strong> spectacular music halls and<br />

designed to rival <strong>the</strong> dominance of<br />

Hollywood cinema in <strong>the</strong> mid-1920s<br />

(ironically, <strong>the</strong> director and his star left<br />

for Hollywood soon after). Shot in London,<br />

Cambridge and Berlin, it showc<strong>as</strong>es<br />

<strong>the</strong> high glamour of metropolitan<br />

night life <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> some accomplished<br />

dance routines under <strong>the</strong> art direction<br />

of <strong>the</strong> ‘m<strong>as</strong>ter of atmospheric mysteries’<br />

Paul Leni.<br />

The Golden Butterfly, dir Michael Curtiz, 1926. Courtesy<br />

of Phoebus-<strong>Film</strong>/S<strong>as</strong>cha/ The Kobal Collection.<br />

FriDAY, April 22<br />

7:00pm<br />

steven Arnold special<br />

The artist, photographer and filmmaker<br />

Steven Arnold w<strong>as</strong> a muse and<br />

model of Salvador Dalí who always<br />

referred to Arnold <strong>as</strong> his prince. Andy<br />

Warhol star Holly Woodlawn claimed<br />

that if Warhol’s Factory w<strong>as</strong> typical<br />

New York, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> circle around<br />

Arnold in Los Angeles w<strong>as</strong> Versailles.<br />

Arnold’s work provides a f<strong>as</strong>cinating<br />

bridge between <strong>the</strong> early cross-gender<br />

experiments of Claude Cahun and<br />

Pierre Molinier and what <strong>the</strong> media<br />

<strong>the</strong>orist Gene Youngblood termed <strong>the</strong><br />

‘polymorphous subterranean world of<br />

unisexual transvestism’ that he saw<br />

<strong>as</strong> a hallmark of <strong>the</strong> emerging ‘synaes<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

cinema’ of <strong>the</strong> 1960s. The<br />

screening also pays homage to an innovative—yet<br />

often overlooked—poet of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Beat Generation, ruth weiss, who<br />

stars in all <strong>the</strong> films featured. weiss<br />

worked with Arnold in <strong>the</strong> late-1960s,<br />

and among many o<strong>the</strong>r jobs she did to<br />

support her writing career, w<strong>as</strong> also<br />

that of a chorus girl.<br />

The <strong>program</strong> will be introduced by<br />

Stuart Comer<br />

various incarnations of a tibetan<br />

seamstress<br />

1969, 10 mins.<br />

ruth weiss, Pat Eddy Lowe and Stephen<br />

Kelemen<br />

Costumes by Steven Arnold<br />

“Originally, it w<strong>as</strong> to be a serious look<br />

at Westerners influenced by E<strong>as</strong>tern<br />

trends. As it developed, however it<br />

became much more humorous with<br />

characters in yoga positions with high<br />

heels and smoking cigarettes at <strong>the</strong><br />

same time.” Stephanie Farago<br />

messages, messages<br />

1972, 23 mins.<br />

With ruth weiss, The Joseph, Pandora<br />

Costumes by Steven Arnold<br />

“A journey of <strong>the</strong> psyche into <strong>the</strong> world<br />

of <strong>the</strong> unconscious. Made when Wiese<br />

and Arnold were students at <strong>the</strong> San<br />

Francisco Art Institute, <strong>the</strong> (...) film<br />

is influenced by Dalí, Buñuel and <strong>the</strong><br />

German expressionists.” Michael Wiese<br />

<strong>the</strong> liberation of mannique<br />

mechanique<br />

1967, 15 mins.<br />

With Sonia Magill and ruth weiss<br />

Costumes by Steven Arnold<br />

Frame enlargement from Messages, Messages,<br />

dir Steven Arnold, 1972. © Steven Arnold Archives.<br />

Frame enlargement from The Liberation of <strong>the</strong><br />

Mannique Mechanique, dir Steven Arnold, 1967.<br />

© Steven Arnold Archives.<br />

Loosely b<strong>as</strong>ed on William A. Seiter’s<br />

1948 film One Touch of Venus, Arnold’s<br />

first film is a macabre, decadent and<br />

ambiguous work presenting mannequins<br />

and models who travel through<br />

strange universes.

MUSEUM OF THE MOVING IMAGE<br />

sAturDAY, April 23<br />

2:00pm<br />

cobra Woman<br />

Dir. Robert Siodmak, 1944, 117 mins.<br />

With Maria Montez, John Hall, Sabu<br />

Costumes by Vera West, sets Russel A.<br />

Gausman, Ira Webb<br />

A star of Universal’s Technicolor<br />

adventure films in <strong>the</strong> 1940s, <strong>the</strong><br />

Dominican-born siren Maria Montez<br />

became <strong>the</strong> centrepiece of Jack Smith’s<br />

Hollywood idolatry two decades later.<br />

(Smith famously singled Montez out in<br />

his essay “The Perfect <strong>Film</strong>ic Appositeness<br />

of Maria Montez.”) The star who<br />

founded her own fan club and who<br />

reportedly once exclaimed “When I see<br />

myself on <strong>the</strong> screen, I am so beautiful,<br />

I jump for joy” w<strong>as</strong> a blueprint for <strong>the</strong><br />

(admittedly more knowing and parodic)<br />

campness and narcissism of Jack<br />

Smith’s stars. With reference to Montez,<br />

Smith stated that bad acting can in<br />

fact expose a priceless slice of life, an<br />

approach echoed in Andy Warhol’s cinema.<br />

In Cobra Woman Montez is c<strong>as</strong>t in<br />

a dual role <strong>as</strong> Tollea of <strong>the</strong> South Se<strong>as</strong><br />

and her evil sister Naja, priestess of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Cobra People on a forbidden island.<br />

The film showc<strong>as</strong>es her charms in Vera<br />

West’s sensuously soft, p<strong>as</strong>tel gowns<br />

<strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> more gaudy outfits. West<br />

w<strong>as</strong> a former f<strong>as</strong>hion designer trained<br />

by Lucile and became <strong>the</strong> doyenne of<br />

costume design for horror and monster<br />

movies in <strong>the</strong> 1930s and 1940s.<br />

Frame enlargement from Cobra Woman, dir Robert Siodmak, 1944.<br />

4:30pm<br />

Flaming creatures<br />

and sensuous ple<strong>as</strong>ures<br />

Total running time 55 mins.<br />

Flaming creatures<br />

Dir. Jack Smith, 1963, 43 mins.<br />

With Francis Francine, Sheila Bick, Mario<br />

Montez, Joel Markman<br />

Costumes by Jack Smith and actors<br />

Flaming Creatures, dir Jack Smith, 1963. Courtesy<br />

of F<strong>as</strong>hion in <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Festival</strong> and The <strong>Film</strong>-Makers’ Cooperative.<br />

Deemed obscene by New York State,<br />

Smith’s revolutionary Flaming Creatures<br />

is an elusive m<strong>as</strong>terpiece which<br />

continues to f<strong>as</strong>cinate. Shot in blackand-white<br />

on outdated film stock,<br />

it reproduces some of <strong>the</strong> sensuous<br />

ple<strong>as</strong>ures and high glamor from Hollywood’s<br />

golden days, especially referencing<br />

such stars <strong>as</strong> Marlene Dietrich and<br />

Smith’s beloved Maria Montez. He gives<br />

his cross-dressed actors <strong>the</strong> freedom<br />

to preen, dance, and play<strong>full</strong>y inhabit<br />

<strong>the</strong> rapturous and exotic fant<strong>as</strong>ies of<br />

Hollywood cinema. Through a combination<br />

of fant<strong>as</strong>tic tableau-vivant compositions<br />

and cinéma vérité camerawork,<br />

Smith brilliantly transforms his b<strong>as</strong>ic<br />

set and thrift store ‘couture’ into a dazzling,<br />

Sternberg-like mise-en-scène.<br />

<strong>the</strong> most Wonderful Fans<br />

of <strong>the</strong> World<br />

(De mooiste waaiers ter wereld)<br />

Dir. unknown, 1927, Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands/<br />

France, 12 mins.<br />

With Pépa Bonafé; Komarova, Korgine,<br />

Sergine; John Tiller Follies Stars<br />

This is a luxuriously stencilled short<br />

film shot in France and distributed<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands in 1927. Like <strong>the</strong><br />

better-known <strong>full</strong>-feature La Revue des<br />

revues, it w<strong>as</strong> filmed on <strong>the</strong> stage of a<br />

Parisian music hall, only this time it is<br />

considerably snappier and presented<br />

without an over-arching narrative<br />

framework. The film includes Orientalist<br />

numbers such <strong>as</strong> “In <strong>the</strong> Temple of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Fakirs” and “The Chinese Fan” and<br />

makes great use of close-ups.<br />

7:00pm<br />

Drag glamour<br />

total running time 95 mins.<br />

Frame enlargement from The Most Wonderful Fans<br />

of <strong>the</strong> World, dir unknown, 1927. Courtesy EYE <strong>Film</strong><br />

Institute Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands<br />

This <strong>program</strong> pairs Jose Rodriguez-<br />

Soltero’s lavish Lupe with Ron Rice’s<br />

landmark psychedelic m<strong>as</strong>terpiece<br />

Chumlum. It features two of <strong>the</strong> most<br />

accomplished uses of superimposition<br />

in underground film, transporting drag<br />

glamor into a psychedelic, cubist-like<br />

dimension.

MUSEUM OF THE MOVING IMAGE<br />

The screenings will be followed with a<br />

panel discussion about <strong>the</strong> legacy of<br />

<strong>the</strong> queer aes<strong>the</strong>tic where <strong>the</strong> spectacle<br />

of f<strong>as</strong>hion plays a dominant role, from<br />

<strong>the</strong> shimmering dresses in Kenneth<br />

Anger’s Puce Moment to Jack Smith’s<br />

reimaging of <strong>the</strong> 1940s’ Hollywood<br />

Orientalism, to <strong>the</strong> stunning, surreal<br />

imagery of Steven Arnold. Ronald<br />

Gregg, Ela Troyano, Stuart Comer and<br />

Agosto Machado will explore <strong>the</strong> designs<br />

and production of <strong>the</strong>se visionary<br />

spectacles, <strong>the</strong> wearing and posturing<br />

of costume and make-up, and <strong>the</strong> cinematography<br />

that brought <strong>the</strong>se visionary<br />

spectacles to excite and haunt our<br />

imaginations.<br />

lupe<br />

Dir. Jose Rodriguez-Soltero, 1966, 50 mins.<br />

With Mario Montez, Charles Ludlam<br />

Costumes by Montez Creations<br />

A visually stunning celebration of <strong>the</strong><br />

life and death of Mexican Hollywood<br />

star Lupe Velez, Rodriguez-Soltero’s<br />

film is an ecstatic explosion of color,<br />

costume, music, camp performance,<br />

and multiple superimpositions. Unconstrained<br />

by any given style, Rodriguez-<br />

Soltero drew inspiration from new wave<br />

and experimental film; Latin American,<br />

pop and cl<strong>as</strong>sical music; tr<strong>as</strong>h culture;<br />

experimental <strong>the</strong>ater, and Kenneth Anger’s<br />

exposé Hollywood Babylon. Lupe<br />

is also a love poem to <strong>the</strong> underground<br />

star Mario Montez who designed his<br />

own sensational costumes and took<br />

immense cultist ple<strong>as</strong>ure in identifying<br />

with <strong>the</strong> tragic Latino star.<br />

chumlum<br />

Dir. Ron Rice, 1964, 45 mins.<br />

With Jack Smith, Beverly Grant, Mario<br />

Montez<br />

Costumes Jack Smith and actors<br />

“Before his untimely death in Mexico<br />

in 1964, Ron Rice w<strong>as</strong> among <strong>the</strong> most<br />

charismatic figures of <strong>the</strong> New York<br />

underground. His Chumlum is beauti-<br />

<strong>full</strong>y disconcerting. Intricate superimpositions<br />

mix indoor and outdoor milieus<br />

and <strong>the</strong> capers of a colorful gaggle<br />

which includes Jack Smith and Mario<br />

Montez <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong>y loll about, pursue, and<br />

listlessly fondle each o<strong>the</strong>r in a riot<br />

of costume and color. Experimental<br />

musician (and Velvet Underground<br />

drop-out) Angus MacLise composed<br />

<strong>the</strong> spacey soundtrack.” Juan Antonio<br />

Suárez<br />

sunDAY, April 24<br />

2:00pm<br />

<strong>the</strong> merry Widow<br />

Frame enlargement from Chumlum, dir Ron Rice, 1964. Courtesy<br />

of F<strong>as</strong>hion in <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Festival</strong> and The <strong>Film</strong>-makers’ Cooperative.<br />

Dirs. Erich von Stroheim, Monta Bell,<br />

1925, 137 mins.<br />

With Mae Murray, John Gilbert<br />

Costumes by Adrian, costume supervision<br />

by Richard Day and Erich von<br />

Stroheim; set decoration Cedric Gibbons<br />

and Richard Day<br />

16mm print from George E<strong>as</strong>tman House<br />

Live music by Donald Sosin<br />

With her career extinguished by <strong>the</strong> arrival<br />

of sound, Mae Murray’s sensuous<br />

charms remain linked with <strong>the</strong> silent<br />

era. Following <strong>the</strong> stereotype, MGM<br />

c<strong>as</strong>t <strong>the</strong> former Ziegfeld girl <strong>as</strong> a shimmering<br />

follies dancer who performs<br />

her routines in provokingly “abbreviated<br />

costumes.” But <strong>the</strong> film takes <strong>the</strong><br />

routine glamorisation of <strong>the</strong> actress<br />

to ano<strong>the</strong>r level. Given that von Stroheim<br />

openly scorned high-maintenance<br />

stars and Murray in particular, it is<br />

likely that <strong>the</strong> indulgence in close-ups<br />

of her face ba<strong>the</strong>d in a golden aura of<br />

back-lighting is down to cameraman<br />

Oliver Marsh who, being one of four<br />

cinematographers on <strong>the</strong> set, reportedly<br />

worked <strong>as</strong> much under Murray’s<br />

direction <strong>as</strong> under von Stroheim’s. The<br />

director’s own agenda w<strong>as</strong> to use an<br />

adaptation of Franz Lehar’s famous<br />

operetta to comment on <strong>the</strong> decadence<br />

of European aristocracy by explicitly<br />

foregrounding <strong>the</strong>mes of sexual lust,<br />

voyeuristic ple<strong>as</strong>ure, and fetishism—<br />

much of which got lost in <strong>the</strong> editing<br />

room. The Merry Widow shows Murray<br />

in some dazzling costumed entrées.<br />

The satin-velvet dress held on a diamond<br />

necklace and complete with<br />

birds-of-paradise headpiece worn in <strong>the</strong><br />

triumphal Waltz scene w<strong>as</strong> designed<br />

by <strong>the</strong> young Adrian who got his first<br />

big break in Hollywood partly thanks<br />

to Murray. The film w<strong>as</strong> originally shot<br />

with Technicolor sequences.<br />

The Merry Widow, dir Erich von Stroheim, 1925. Courtesy of BFI.

Salomé, dir Charles Bryant, 1923. Courtesy of United Artists / The Kobal Collection / Rice.<br />

4:30pm<br />

salomé<br />

Dir. Charles Bryant, 1923, 74 mins.<br />

With Alla Nazimova, Mitchell Lewis<br />

Costume and sets by Natacha Rambova<br />

With an introduction to <strong>the</strong> work of Natacha<br />

Rambova by Pat Kirkham<br />

Accompanied by music from Donald<br />

Sosin<br />

The cult status that Salomé enjoys today<br />

owes much to <strong>the</strong> outlandish, highly<br />

stylised sets and costumes à la Aubrey<br />

Beardsley. The designer Natacha Rambova<br />

w<strong>as</strong> a protégé of <strong>the</strong> lead actress<br />

and producer Nazimova who reportedly<br />

sank much of her own money in <strong>the</strong> film.<br />

Despite being a box-office failure <strong>the</strong><br />

film remains a landmark in <strong>the</strong> history<br />

of cinema, bridging <strong>the</strong> mainstream and<br />

<strong>the</strong> avant-garde. Its radical modernist<br />

aes<strong>the</strong>tic, camp stylisations and deliberately<br />

exaggerated acting is a departure<br />

from <strong>the</strong> turn-of-<strong>the</strong>-century portrayals<br />

of Salomé <strong>as</strong> an overtly eroticized<br />

seductress. Nazimova’s film is arguably<br />

less exhibitionist than it is a comment<br />

on exhibitionism (one reviewer even complained<br />

it had little worthy of censorship)<br />

<strong>as</strong> it <strong>the</strong>matizes looking, voyeurism,<br />

and transgressive sexual desire—an apt<br />

homage to Oscar Wilde indeed.<br />

6:30pm<br />

F<strong>as</strong>hions of 1934<br />

Dir. William Dieterle, 1934<br />

With William Powell, Bette Davis.<br />

Costume by Orry-Kelly, musical numbers<br />

by Busby Berkeley.<br />

New 35mm print courtesy of <strong>the</strong> Packard<br />

Humanities Institute.<br />

F<strong>as</strong>hions of 1934 is one of a long line<br />

of films from <strong>the</strong> 1930s and 1940s that<br />

exploited <strong>the</strong> success of New York’s super-revues<br />

such <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ziegfeld Follies<br />

and Frolics, <strong>the</strong> Earl Carroll Vanities,<br />

or George White’s Scandals. Its musical<br />

F<strong>as</strong>hions of 1934, dir William Dieterle, 1934. Courtesy of Warner Bros / The Kobal Collection.<br />

number “Spin a Little Web of Dreams”<br />

h<strong>as</strong> Busby Berkeley’s signature all over<br />

it—here he combined to great effect<br />

<strong>the</strong> sensuousness of <strong>the</strong> follies’ costuming<br />

and décor with his trademark<br />

kaleidoscopic choreography. As if this<br />

w<strong>as</strong> not enough, <strong>the</strong> film displays some<br />

remarkable gowns courtesy of Hollywood<br />

favourite, Orry-Kelly (who himself<br />

had designed sets and costumes for <strong>the</strong><br />

Scandals). As its title suggests, F<strong>as</strong>hions<br />

of 1934 is set in <strong>the</strong> f<strong>as</strong>hion industry<br />

and h<strong>as</strong> a good old dig at many<br />

a sensitive issue at its heart – from<br />

creativity versus commerce, originality<br />

versus copy and exclusivity versus<br />

m<strong>as</strong>s-availability, to <strong>the</strong> rivalry between<br />

Paris and New York.

<strong>the</strong> graduate center, cuny<br />

seminArs At tHe grADuAte center<br />

19 April and 2 May 2011<br />

The Graduate Center seminars will bring toge<strong>the</strong>r international scholars with<br />

an interest in f<strong>as</strong>hion and film to debate issues of costume, movement and<br />

spectacle in cinema. The seminars will also screen rare footage ranging from<br />

early European and American film, to underground cinema and contemporary<br />

f<strong>as</strong>hion film. Free entry. Tickets at <strong>the</strong> door.<br />

tuesday, April 19<br />

2:30 - 5:30pm<br />

<strong>the</strong> eleb<strong>as</strong>h recital Hall<br />

metamorphoses: clothing in<br />

motion from early cinema to<br />

contemporary F<strong>as</strong>hion <strong>Film</strong><br />

This seminar will look at clothing and<br />

adornment in film <strong>as</strong> a device of ple<strong>as</strong>ure<br />

and sartorial knowledge; one that h<strong>as</strong><br />

had a long history in shaping cinema’s<br />

aes<strong>the</strong>tic languages. It will articulate<br />

some of <strong>the</strong> connections between early,<br />

experimental and underground cinema,<br />

<strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> contemporary “f<strong>as</strong>hion<br />

film” and more, <strong>as</strong>king questions about<br />

stillness and motion, <strong>the</strong> material specificities<br />

of clothing on <strong>the</strong> screen, and <strong>the</strong><br />

contexts (technological and o<strong>the</strong>r) of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

Untitled film still by Erwin Blumenfeld, 1958–64, presented in SHOWstudio’s<br />

Experiments in Advertising: The <strong>Film</strong>s of Erwin Blumenfeld, 2006. Courtesy of <strong>the</strong><br />

Erwin Blumenfeld Estate and SHOWstudio.com.<br />

production and dissemination that allowed<br />

for dress to be a prominent player<br />

in new experiments in image-making.<br />

Moderator: Eugenia Paulicelli<br />

Respondent: Robert Singer<br />

Speakers: Marketa Uhlirova − Costume<br />

<strong>as</strong> a Special Effect: Early Cinema and<br />

Beyond; Antonia Lant − Painted or Pure?<br />

Sartorial Knowledge in Griffith’s The<br />

Painted Lady; Ronald Gregg − Orientalism<br />

and F<strong>as</strong>hion in 1960s Underground<br />

<strong>Film</strong>; Penny Martin − F<strong>as</strong>hion <strong>Film</strong> and<br />

Before<br />

monday, may 2<br />

5:00 - 7:30pm<br />

skylight<br />

F<strong>as</strong>hion in <strong>Film</strong>: europe and<br />

America<br />

Since <strong>the</strong> emergence of cinema in <strong>the</strong><br />

late-19th century, <strong>the</strong> role of costume,<br />

fabrics and f<strong>as</strong>hion h<strong>as</strong> been crucial<br />

in conveying an aes<strong>the</strong>tic dimension<br />

and establishing a new sensorial and<br />

emotional relationship with viewers.<br />

Through <strong>the</strong> interaction of f<strong>as</strong>hion,<br />

costume and film it is possible to gauge<br />

a deeper understanding of <strong>the</strong> cinematic,<br />

its complex history, and <strong>the</strong><br />

mechanisms underlying modernity, <strong>the</strong><br />

construction of gender, urban transformations,<br />

consumption, technological<br />

and aes<strong>the</strong>tic experimentation.<br />

Moderator: Amy Herzog<br />

Respondent: Jerry Carlson<br />

Speakers: Jody Sperling − Loïe Fuller<br />

and Early Cinema; Caroline Evans −<br />

Early F<strong>as</strong>hion Shows and <strong>the</strong> “Cinema<br />

of Attractions,” c. 1900-1925; Michelle<br />

Tolini Finamore − “Exploitation” in Silent<br />

Cinema: Poiret and Lucile on <strong>Film</strong>; Drake<br />

Stutesman − Spectacular Hats! A New<br />

Kind of Identity in a New Kind of Love<br />

(1963)<br />

Presented by <strong>the</strong> Center for <strong>the</strong> Humanities;<br />

Concentration in F<strong>as</strong>hion<br />

Studies, MA in F<strong>as</strong>hion: Theory, History,<br />

Practice in <strong>the</strong> MA Liberal Studies<br />

Program, <strong>Film</strong> Studies, Women’s Studies<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Center for Gay and Lesbian<br />

Studies in conjunction<br />

with <strong>the</strong> F<strong>as</strong>hion in <strong>Film</strong><br />

<strong>Festival</strong>.<br />

A frame enlargement from a film showing a mannequin at Worth, c. 1926-7. Courtesy of Caroline Evans and Lobster <strong>Film</strong>s.

yale university<br />

“secrets oF tHe orient”:<br />

DurAtion, movement, AnD costume in tHe cinemAtic<br />

experience oF tHe eAst<br />

A symposium with screenings at Yale university<br />

11 - 12 November 2011, Whitney Humanities Center<br />

Borrowing <strong>the</strong> title of <strong>the</strong> 1928 German-French studio spectacular, this<br />

symposium will expand on <strong>the</strong> Orientalist strand in Birds of Paradise. It will<br />

consider <strong>the</strong> movement, duration, texture and o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>as</strong>pects of “dressing” film<br />

through costume, sets and props <strong>as</strong> having played a crucial role in defining<br />

Western visions of <strong>the</strong> E<strong>as</strong>t throughout <strong>the</strong> 20th century. It will also address <strong>the</strong><br />

use of costume <strong>as</strong> an important aes<strong>the</strong>tic device in Asian cinema. Participating<br />

speakers will include Charles Musser, Anapuma Kapse, Amy Herzog, Alistair<br />

O’Neill, Eugenia Paulicelli, Becky Conekin and Ronald Gregg.<br />

For more details check our websites nearer <strong>the</strong> time:<br />

f<strong>as</strong>hioninfilm.com; yale.edu/filmstudies<strong>program</strong>/events.html<br />

Hero, dir. Yimou Zhang, 2002. Courtesy of BFI.<br />

COSTuME IN EARly CINEMA,<br />

THE AESTHETIC OF OpUlENCE,<br />

AND THE lIVING SCREEN<br />

Marketa uhlirova<br />

While footage presenting f<strong>as</strong>hion is extremely scarce in<br />

<strong>the</strong> first decade of film, early cinema never<strong>the</strong>less demonstrates a profound f<strong>as</strong>cination<br />

with costume and artifice. As early <strong>as</strong> 1894, William Heisse and William<br />

K.L. Dickson at Edison Manufacturing Company filmed Carmencita and Annabelle<br />

Whitford Moore performing serpentine and butterfly dances. 1 In each of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

films <strong>the</strong> spectacular costume itself w<strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> key attraction on show. B<strong>as</strong>ed on <strong>the</strong><br />

groundbreaking stage performances of <strong>the</strong> American dancer Loïe Fuller, films of<br />

serpentine and butterfly dances, and <strong>the</strong>ir variations, formed an entire sub-genre<br />

within early cinema, and <strong>the</strong>ir impact on <strong>the</strong> emerging medium w<strong>as</strong> considerable.<br />

As, indeed, w<strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> impact of capturing billowing costumes in motion, so much<br />

so that cinematic dances “à la mannière Loïe Fuller” or “genre Loïe Fuller” may be<br />

seen <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> bridge between two conceptions of early cinema: one that records <strong>the</strong><br />

external world, <strong>as</strong> in Edison and Lumière, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r a cinema that privileges <strong>the</strong>atrical<br />

artistry and artifice to forge a new “aes<strong>the</strong>tic of opulence,” 2 <strong>as</strong> championed<br />

by Georges Méliès and best exploited by filmmakers at Pathé frères, most notably<br />

G<strong>as</strong>ton Velle, Segundo de Chomón and Ferdinand Zecca.<br />

Perhaps inevitably, <strong>the</strong> cinematic dance “à la Fuller” is<br />

generally anchored within a discussion of its originator<br />

and innovator. Fuller’s w<strong>as</strong> essentially an update of<br />

<strong>the</strong> nineteenth-century skirt and veil dance. She built<br />

on <strong>the</strong>se dances’ premise of using <strong>the</strong> skirt <strong>as</strong> a pivotal<br />

element in a performance—its capacity to hide and<br />

reveal <strong>the</strong> body, and its unique expressivity when in<br />

motion—but she radically transformed a popular variety<br />

entertainment into an avant-garde form, creating a<br />

thoroughly new vision whose significance extended well<br />

beyond <strong>the</strong> world of dance and <strong>the</strong> music hall. Throughout<br />

her career, Fuller continuously re-modeled her<br />

dresses, usually made from fine gossamer silk, gradually<br />

extending <strong>the</strong>m to almost outlandish proportions—to<br />

<strong>as</strong> much <strong>as</strong> 100 yards around <strong>the</strong> skirt. 3 Depending on <strong>the</strong> type of dance, <strong>the</strong>se<br />

dresses had giant wings attached to <strong>the</strong>ir torso, or were ga<strong>the</strong>red at <strong>the</strong> neck with<br />

<strong>the</strong> arms manipulating <strong>the</strong>m from underneath with <strong>the</strong> help of wooden wands. By<br />

undulating and swirling <strong>the</strong> excess of fabric, Fuller evoked <strong>the</strong> effects of an entire<br />

repertoire of natural phenomena such <strong>as</strong> waves, whirls and fire, creatures such <strong>as</strong><br />

butterflies, bats and serpents, and flowers such <strong>as</strong> violets and lilies. Her costumes<br />

appeared to <strong>as</strong>sume a life of <strong>the</strong>ir own <strong>as</strong> a constant stream of new forms appeared<br />

and disappeared, <strong>the</strong>ir monumentality fur<strong>the</strong>r dramatised by a phant<strong>as</strong>magorical<br />

orchestra of optical stage effects, especially projections of colored light.<br />

The serpentine and <strong>the</strong> butterfly dance proved to be<br />

among early cinema’s most persistent subjects. With numerous variations performed<br />

by scores of variety and vaudeville dancers for companies including, in<br />

addition to Edison, <strong>the</strong> American Mutoscope and Biograph, Lumière, Gaumont,<br />

Pathé and o<strong>the</strong>rs, <strong>the</strong> dances were a permanent fixture throughout cinema’s first<br />

decade. In line with how <strong>the</strong> serpentine dance appeared on <strong>the</strong> popular stage,<br />

cinema made it <strong>the</strong> subject of various parodies (Leopoldo Fregoli’s La danse serpentine<br />

de Fregoli, 1897, Birt Acres’s and Robert W. Paul’s Performing Animals/

Skipping Dogs, 1895), presented it <strong>as</strong> a curiosity (La Serpentine dans la cage aux<br />

fauves, Ambroise-François, 1900), and integrated it into more complex, multipleshot<br />

trick films where it w<strong>as</strong> combined with additional effects such <strong>as</strong> magical<br />

transformations (Pathé’s 1905 Loïe Fuller, attributed to Lucien Nonguet, where a<br />

bat turns into a dancer) and flames and smoke (Georges Méliès’s Danse du feu,<br />

1899 and Segundo de Chomón’s La Creación de la Serpentina, 1908, and La Danza<br />

del fuego, 1909), and it w<strong>as</strong> used to form near-psychedelic multi-corps ballets<br />

(La Creación de la Serpentina or Cines’s Le Farfalle, 1907, which is also one of <strong>the</strong><br />

most exquisite choreographies in this category). 4<br />

All this is testimony to <strong>the</strong> enormous contemporary<br />

f<strong>as</strong>cination with Fuller. However, to argue that cinema’s<br />

Fullerian dances were purely an extension of Fuller’s<br />

remarkable achievements risks overlooking <strong>the</strong>ir significance<br />

within cinema. Such an argument implies cinema’s<br />

technological inadequacies vis-à-vis <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ater, c<strong>as</strong>ting<br />

it <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> medium that w<strong>as</strong> unable to match <strong>the</strong> complexity<br />

of Fuller’s stagecraft. It highlights cinema’s pedestrian<br />

nature <strong>as</strong> it transported <strong>the</strong> serene, multi-dimensional<br />

aes<strong>the</strong>tic experience of <strong>the</strong> serpentine dance into <strong>the</strong> vernacular. After all, Fuller’s<br />

conspicuous absence from cinema itself suggests this view. 5<br />

Yet, <strong>the</strong> short films of Annabelle, Ameta, Crissie Sheridan,<br />

Bob Walter and o<strong>the</strong>rs play an important role in early cinema—not so much<br />

<strong>as</strong> a historical document but, ra<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>as</strong> a unique type of cinematic image. Firstly,<br />

and on <strong>the</strong> most fundamental level, <strong>the</strong> Fullerian dances were embraced <strong>as</strong> an<br />

ideal medium to exhibit two of film’s vital properties: motion and time. Positioned<br />

more or less centrally upon a plain stage with darkened background, practically<br />

isolated from all o<strong>the</strong>r stimuli, <strong>the</strong> dancer and her changing shapes embodied<br />

constant change. The soft, organic whirling of her costume<br />

conveyed a dynamism and fluidity that made <strong>the</strong><br />

serpentine dance an appropriate analogue of cinema’s<br />

capacity to present a seamless continuum. 6<br />

Secondly, cinematic dances à<br />

la Fuller ushered cinema towards a concern with visual<br />

spectacle that mimicked <strong>the</strong> elaborate stage effects of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atrical machinery (la machinerie théâtrale), an<br />

approach that w<strong>as</strong> soon more <strong>full</strong>y explored by Méliès,<br />

closely followed by filmmakers at Pathé and elsewhere.<br />

Thirdly, <strong>the</strong>se cinematic<br />

dances are inextricably linked to <strong>the</strong> emergence of color<br />

in cinema, which, in turn, cannot be divorced from<br />

<strong>the</strong> discourse of opulence and magic. Edison’s 1894<br />

Annabelle Serpentine Dance is among <strong>the</strong> earliest color<br />

films in <strong>the</strong> history of cinema, and it is also this—or<br />

possibly ano<strong>the</strong>r Annabelle film from 1894–5—that w<strong>as</strong><br />

one of <strong>the</strong> first color films to be exhibited in a public<br />

projection. 7 Cinema’s Fullerian dances were colored<br />

in a bid to imitate <strong>the</strong> stage effects of Fuller’s projections<br />

of multi-colored lights onto <strong>the</strong> moving costumes,<br />

and were typically listed <strong>as</strong> ideal subjects for coloring. 8<br />

Much like Fuller’s claims that she “adapt[ed] <strong>the</strong> movements<br />

of [her] dance to th[e colors’] effects,” 9 <strong>the</strong>re are<br />

also many catalog descriptions of trick and féerie films<br />

by Méliès and Pathé which show that color w<strong>as</strong> clearly<br />

considered an invaluable tool, and indeed formed an integral<br />

part in <strong>the</strong> planning of effects. The 1901 Charles<br />

Urban catalog, for example, made this point quite explicitly<br />

in its description of Méliès’s Danse du feu: “This<br />

film w<strong>as</strong> especially made up for <strong>the</strong> purpose of colouring<br />

which is applied in a most surprising and artistic<br />

manner, incre<strong>as</strong>ing <strong>the</strong> wonderful effect tenfold.” 10<br />

There is every re<strong>as</strong>on to believe that <strong>the</strong> dominant motifs<br />

employed to define <strong>the</strong> aes<strong>the</strong>tic of opulence—butterflies,<br />

flowers, fans,<br />

costumes and ornamental<br />

interiors—were<br />

specifically chosen <strong>as</strong><br />

a means of presenting<br />

color to its most<br />

picturesque effect. Like<br />

costume in motion,<br />

color w<strong>as</strong> of course ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

device by which<br />

constant change could<br />

be illustrated, and, <strong>as</strong><br />

Charles Musser notes,<br />

also one through which<br />

early cinema’s m<strong>as</strong>culine<br />

appeal could be<br />

transcended. 11<br />

Frame enlargement from Le Merveilleux éventail vivant,<br />

dir. Georges Méliès, 904. Courtesy of Lobster <strong>Film</strong>s.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, <strong>the</strong> group of<br />

serpentine and butterfly dances anticipates a conception of <strong>the</strong> cinematic image<br />

<strong>as</strong> an enclosed and self-contained space; a conception that soon comes to<br />

define Mélièsian cinema with its “artificially arranged scenes.” The dances make<br />

maximum impact when <strong>the</strong> costume fills <strong>the</strong> visual field with its presence—in<br />

many c<strong>as</strong>es, <strong>the</strong> moving costumes quite literally demarcate <strong>the</strong> boundaries of <strong>the</strong><br />

frame. Fanning out and sweeping across <strong>the</strong> screen, <strong>the</strong>ir fabric presents itself<br />

<strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> screen’s moving counterpart. This doubling becomes even more apparent<br />

in a number of <strong>the</strong> so-called “transformation scenes” 12 where actors face <strong>the</strong><br />

static camera and metamorphose into screens through simple gestures of opening<br />

overized wings, cloaks or peacock tails which can <strong>the</strong>n be fur<strong>the</strong>r animated,<br />

especially with color variations.<br />

These so-called “transformation scenes” are characteristic<br />

of two genres within early cinema: <strong>the</strong> trick film and <strong>the</strong> féerie. Both were<br />

developed by Méliès 13 and drew heavily on <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atrical féerie and stage magic.<br />

Méliès w<strong>as</strong> an ardent fan and also a practitioner of both (<strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> impresario in his<br />

own magic <strong>the</strong>atre, <strong>the</strong> Théâtre Robert-Houdin). His films adopted <strong>the</strong>se <strong>as</strong> well<br />

<strong>as</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r traditions of nineteenth-century popular entertainment and science to<br />

conjure a world of supernatural wonders, introducing into <strong>the</strong> language of cinema<br />

<strong>the</strong> baroque concept of <strong>the</strong> marvelous (le merveilleux). 14 Méliès himself called this<br />

brand of cinema “fant<strong>as</strong>tical scenes” (les vues fant<strong>as</strong>tiques), positioning <strong>the</strong>m in<br />

direct contr<strong>as</strong>t to “ordinary subjects” (les vues ordinaires). He emph<strong>as</strong>ized that<br />

besides transformation “<strong>the</strong>re is also a great number [of films] involving tricks,<br />

<strong>the</strong>atrical machinery, mise-en-scène, optical illusions.” 15 This suggests that<br />

transformation w<strong>as</strong> far from being <strong>the</strong> only major ingredient in his box of tricks.<br />

In Méliès’s cinema, <strong>the</strong>re is a shift from a primary sense<br />

of amazement at <strong>the</strong> technological wonder of motion—<br />

<strong>the</strong> key <strong>as</strong>pect of what Tom Gunning h<strong>as</strong> called <strong>the</strong><br />

“aes<strong>the</strong>tic of <strong>as</strong>tonishment” 16 —toward an amazement at<br />

<strong>the</strong> manifestation of visual opulence in its imaginative<br />

excess. Motion here is devised <strong>as</strong> a structuring tool in<br />

<strong>the</strong> staging of “special effects” that animate <strong>the</strong> lavish<br />

mises-en-scène. For Méliès, <strong>the</strong> artistry and charm of<br />

décor and costumes w<strong>as</strong> <strong>as</strong> important <strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong> originality<br />

of his tricks or that of <strong>the</strong> “star attraction.” 17 Méliès w<strong>as</strong><br />

particularly proud of pointing cinema towards aes<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

concerns derived from <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ater, claiming that he<br />

gave cinema a new le<strong>as</strong>e of life, effectively rescuing it<br />

from being a one-hit wonder. He w<strong>as</strong> also proud that<br />

he designed his own sets, décor and costumes, and<br />

that he w<strong>as</strong> generally present at every stage in a film’s<br />

production, and it w<strong>as</strong> this auteurist approach that enabled<br />

Pathé, with its industrial model of production, to<br />

quickly establish itself <strong>as</strong> a serious rival in <strong>the</strong> trick film<br />

and féerie genres.<br />

The aes<strong>the</strong>tic of opulence is characterised by <strong>the</strong> “grand<br />

spectacle” of butterflies, fairies and devils who—grace<strong>full</strong>y or grotesquely—pose<br />

and gesture with <strong>the</strong>ir wings and cloaks, <strong>as</strong> in Méliès’s Conte de la grand-mère<br />

et le rêve de l’enfant (1908), or de Chomón’s La Légende du fantôme (1908), Le<br />

charmeur (1906) and Le Spectre rouge (1907); exotic vegetation, <strong>as</strong> in Méliès’s La<br />

Chrysalide et le papillon d’or (1901); palatial interiors and multi-corps processions<br />

and ballets, <strong>as</strong> in Méliès’s Le Palais des Mille et une nuits (1905); “optical effects”<br />

such <strong>as</strong> pyrotechnics, showers of gold coins and rays of light emanating from bodies,<br />

<strong>as</strong> in de Chomón’s Le scarabée d’or (1907), Zecca’s Ali Baba et les quarante<br />

Frame enlargement from Métempsycose, dir Segundo de Chomón, 1907. Courtesy of AFF/CNC, France.<br />

voleurs (1902) or Velle’s La poule aux oeufs d’or (1905); or dazzling underwater<br />

kingdoms, <strong>as</strong> in Ferdinand Zecca’s Pêcheur de perles (1907). Many of <strong>the</strong>se <strong>the</strong>mes<br />

appear at <strong>the</strong>ir best in <strong>the</strong> so-called apo<strong>the</strong>oses, <strong>the</strong> triumphal scenes and <strong>the</strong> ultimate<br />

glorifications of opulence which typically involve <strong>the</strong> whole troupe in ballets<br />

or o<strong>the</strong>r, more ambitious formations. This is where cinema used and reinvented<br />

some of <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atrical machinery that defined <strong>the</strong> nineteenth-century féerique.<br />

Among all <strong>the</strong> motifs that showc<strong>as</strong>e costume <strong>as</strong> a living<br />

screen, those of women-butterflies (femme-papillon),<br />

women-insects and winged fairies are <strong>the</strong> most persistent<br />

and also <strong>the</strong> most emblematic. These fin-de-siècle<br />

phenomena were already familiar tropes from stage<br />

magic and féerie; one of Méliès’s first cinematic butterfly-women,<br />

in La Chrysalide et le papillon d’or, w<strong>as</strong> in<br />

fact b<strong>as</strong>ed on a famous stage illusion called The Cocoon<br />

(Le Cocon) by French magician Buatier de Kolta 18 shown<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Egyptian Hall in London in 1887, shortly after<br />

Méliès’s own brief stint <strong>the</strong>re. 19 De Kolta’s trick w<strong>as</strong> <strong>the</strong>n recreated again in G<strong>as</strong>ton<br />

Velle’s Métamorpsoses du papillon (1904) and de Chomón’s Maripos<strong>as</strong> japones<strong>as</strong>/Papillons<br />

japonais (1908), both of which are colored. Ano<strong>the</strong>r remarkable film<br />

by de Chomón, Métempsycose (1907), w<strong>as</strong> also b<strong>as</strong>ed on an eponymous popular<br />

magic illusion which w<strong>as</strong> essentially a variation on <strong>the</strong> Pepper’s Ghost. The film’s<br />

main attraction is a female figure who repeatedly opens and closes arms, each<br />

time unveiling a new pair of wings that turn into a cape decorated with motifs<br />

that, once again, evoke Fuller’s early painted costumes.

With his oversized<br />

fan in Le Merveilleux<br />

éventail vivant (1904),<br />

Méliès’s identified<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r excellent opportunity<br />

to create a<br />

living screen. As <strong>the</strong><br />

fan opens, it obscures<br />

completely <strong>the</strong> perspective<br />

view of <strong>the</strong> gardens<br />

at Versailles painted <strong>as</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> scene’s backdrop,<br />

effectively <strong>as</strong>serting<br />

itself <strong>as</strong> a curtain, a<br />

surface on which to exhibit<br />

miraculous acts.<br />

Once open, <strong>the</strong> fan’s<br />

ornamental branches,<br />

decorated in <strong>the</strong> style<br />

of Louis XV, turn into a gallery of seven arcades with women “in gala attire” who<br />

<strong>the</strong>n undergo a series of transformations of dress and accessories. When <strong>the</strong> fan<br />

mounting eventually disappears and gives way to a star-studded globe, <strong>the</strong> women<br />

simply emanate from it like a “human fan,” forming a sculptural tableau vivant.<br />

Méliès’s inspiration for this film came from a hugely successful féerie extravaganza<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Théâtre du Châtelet, The Sun Prince (1889), which bo<strong>as</strong>ted a living fan number<br />

in its apo<strong>the</strong>osis scene, a view that w<strong>as</strong> described by The Era <strong>as</strong> “superb ...<br />

formed of nude fairies over whose forms stream rays of electric light.” 20 The <strong>the</strong>me<br />

w<strong>as</strong> again re-worked later at Pathé with some remarkable results.<br />

It is impossible to divorce <strong>the</strong> f<strong>as</strong>cination with material<br />

splendor in cinema’s “aes<strong>the</strong>tic of opulence” from <strong>the</strong><br />

highly saturated visual culture of <strong>the</strong> late nineteenthcentury<br />

metropolis, where luxury and abundance could<br />

be seen in <strong>the</strong> context of <strong>the</strong> everyday. The modern city<br />

w<strong>as</strong> its own machinerie théâtrale, generating with <strong>the</strong><br />

surplus of commodities and images <strong>the</strong> neur<strong>as</strong><strong>the</strong>nia<br />

and phant<strong>as</strong>magoria <strong>the</strong>orised by Georg Simmel and,<br />

later, Walter Benjamin. The late nineteenth century<br />

w<strong>as</strong> also a time when distinguishing oneself through<br />

nuanced consumer “knowledge” and appearances had<br />

become paramount. Disinterest in—or a lack of—such<br />

urbane sophistication w<strong>as</strong> now more likely to signify<br />

provincialism than moral repugnance. Vis-à-vis this<br />

grown-up (and incre<strong>as</strong>ingly rationalized and bureaucratized)<br />

comsumerism, <strong>the</strong> cinematic marvelous offered<br />

an alternative discourse. It championed a deliberately<br />

old-f<strong>as</strong>hioned and naïve world order, and emph<strong>as</strong>ized<br />

that acquisition of wealth or status w<strong>as</strong> only possible<br />

through supernatural intervention, or dream. In this respect<br />

it subverted <strong>the</strong> contemporary discourse of social<br />

mobility, offering a “retreat from <strong>the</strong> constraints of <strong>the</strong><br />

real or <strong>the</strong> present, … an alternate plane onto which <strong>the</strong><br />

real can be transposed and reimagined.” 21<br />

Frame enlargement from Le Merveilleux éventail vivant, dir. Georges<br />

Méliès, 1904. Courtesy of Lobster films.<br />

engenDering FAust:<br />

tHe veileD lADY in nino oxiliA’s<br />

RApSODIA sAtAnicA<br />

Eugenia paulicelli<br />

Rapsodia satanica, by <strong>the</strong> Turin-b<strong>as</strong>ed writer and director<br />

Nino Oxilia, is a true m<strong>as</strong>terpiece whose value deserves to be recognized and<br />

positioned in <strong>the</strong> wider context of <strong>the</strong> history of cinema in Italy and beyond. It is<br />

especially crucial to see how this early Italian film can be re-read today through<br />

<strong>the</strong> lens of dress and f<strong>as</strong>hion so <strong>as</strong> to capture <strong>the</strong> philosophical underpinnings of<br />

Oxilia’s reinterpretation of <strong>the</strong> Faust legend, its gender implications, and its aes<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

folding and unfolding of his “dance of human p<strong>as</strong>sions.” 1 Unlike o<strong>the</strong>r versions<br />

of Faustian narratives, in Rapsodia it is an elderly woman, Alba d’Oltrevita<br />

(whose name we could translate <strong>as</strong> Dawn beyond Life), played by <strong>the</strong> Italian diva<br />

Lyda Borelli, who makes <strong>the</strong> pact with <strong>the</strong> Devil. The price she is <strong>as</strong>ked to pay to<br />

regain her beauty and youth is to give up love. Youth and beauty are exchanged<br />

for a life devoid of emotion, p<strong>as</strong>sion, and sensuality—almost a contradiction in<br />

terms. This is especially so because in <strong>the</strong> beginning of <strong>the</strong> film, Alba unfolds herself<br />

into younger skin and becomes a femme fatale.<br />

Rapsodia satanica foregrounds <strong>the</strong>mes of <strong>the</strong> fragility of<br />

human actions, emotions, <strong>the</strong> impossibility of divorcing love from youth and life,<br />

<strong>the</strong> transience of human existence and actions and, above all, time and its inherent<br />

slipperiness. All are <strong>the</strong>mes quintessential to this film and perhaps also to<br />

film in general, especially at <strong>the</strong> time of experimentation and advancement in <strong>the</strong><br />

arts and sciences in which Rapsodia w<strong>as</strong> made. And this is ano<strong>the</strong>r re<strong>as</strong>on why<br />

Oxilia’s film is so rich. Time is embedded in <strong>the</strong> cinematic machine in its kineaes<strong>the</strong>tic<br />

multi-dimensionality. The composer Pietro M<strong>as</strong>cagni wrote <strong>the</strong> score for <strong>the</strong><br />

film, signalling artistic collaboration between <strong>the</strong> relatively new cinematographic<br />

art and <strong>the</strong> world of high art, <strong>the</strong>ater and opera. Rapsodia is a big production<br />

conceived <strong>as</strong> an opera totale of <strong>the</strong> Rome-b<strong>as</strong>ed production house, Cines. In its<br />

very title, <strong>the</strong> film offers itself <strong>as</strong> a challenge to <strong>the</strong> tradition of <strong>the</strong> art of storytelling<br />

in <strong>the</strong> age of mechanical reproduction.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> c<strong>as</strong>tle of illusions where Alba lives, anything can<br />

happen. It is <strong>as</strong> if <strong>the</strong> c<strong>as</strong>tle itself were a movie <strong>the</strong>ater<br />